Drawings in Conversation

C. R. Cockerell, Joseph Gwilt and the Royal Exchange Competition

Owing to a faulty gas lamp, on the 10th January 1838 the Royal Exchange in the City of London was destroyed by fire. The loss of the building was seen to be potentially catastrophic for trade in the City and moves were made to expedite the construction of a new exchange through an open architectural competition. Typical of the nineteenth century, in the words of the judges, this competition was an examination and a judgement of each architect’s design. Examination was made primarily through drawings. Each entrant was required to submit a set of orthogonal drawings. The committee specified that perspective drawings were permitted, but only from two specified views. One a street view from the west, the other a courtyard interior. In addition to their predetermined subjects, the committee also specified that all drawings were to be produced in brown or Indian ink. A further decree stated that ‘no model, sketch, perspective, or coloured drawing (save two such perspective drawings as are described in the previous resolution) shall be received’. [1] Some commentators in the architectural press criticised the absence of models in competitions. Others, including the RIBA’s 1837 committee on competitions, proposed that the perspective drawing held primacy in the process of judgement.

On 7 September 1839, following a drawn-out process, the architects Robert Smirke, Joseph Gwilt, and Philip Hardwick were appointed judges. Thirty-eight submitted entries were exhibited for the judges in the Mercers’ Hall. Until a winner was selected the competition was assessed anonymously. Later discovered to be the work of C. R. Cockerell, entry No. 46 was praised by Gwilt as ‘a very extraordinary & fine compos.[ition] and drawing’. [2] Next to this assessment, in the bound volume of his papers, Gwilt sketched a copy of the street view perspective in admiration.

Cockerell’s courtyard view, however, posed questions about the legitimacy of perspectival representation as a valid instrument for architectural judgement. Preliminary studies of this courtyard space were formed from skeletal frames of pencil with heavy ink washes used to roughly delineate light and shade, form and relief. These drawings do not detail the Classical language of the space. Instead their interest is in the juxtaposition of light and shade on surfaces.

Unfortunately only lithograph copies of Cockerell’s final drawing survive. Engraved by George Moore, unlike the early studies the structure of the drawing has been established by assertive line work with layers of ink applied afterwards. Distinct to the other submitted perspective, the street view, the unidentified draftsman in Cockerell’s office, probably Henry Richardson, has set the vanishing point of the drawing at about 3.5 m above the ground plane. Immediately it becomes clear that the drawing is not proposing a reality but merely suggesting one. This suggestion becomes clearer when we realise what the drawing is missing.

In order to depict space in a drawing, especially an interior, the space often has to be manipulated through the removal of portions or the distortion of viewing position. On the upper right of the drawing, behind the authoritative Latin inscription is the spectre of an interior with a barrel-vaulted ceiling, a room that should not be seen from the drawing’s viewpoint. Beneath the inscription, the architrave of the colonnade, running in the direction of the vanishing point, intersects with the fragment of the architrave running across the width of the drawing. Surrounded by figures, two columns from the colonnade have been pruned back to reveal a fuller representation of the space than would be possible in reality. In total three bays of the colonnade and the whole of one façade of the courtyard above the colonnade have been removed. Their absence does not affect the way light structures the courtyard. Therefore we know their removal is not real but for pictorial effect.

To the left of this absence, secondary beams traverse the main structure. Above the column, the stone fragments that form the entablature are stacked above one another. A solitary pilaster, oddly isolated from the façade, rises up in a stack. Unlike J. M. Gandy’s perspective views for John Soane that oscillate between ruin and construction, Cockerell’s drawing is not interested in projecting the construction of the building or its subsequent decay. There is no interest in differentiating between materials or instructions for how these materials might come together in sequence. Instead the interest is tectonic. The drawing wavers between the assemblage and dispersal of abstract elements. Rather than how it will be built, the drawing shows us what will be built through the small objects whose assembly requires the combination of unskilled labour and artisanal work. Other more precise media, specifically the specification and contract, will capture the sequencing and requirements of the building’s construction.

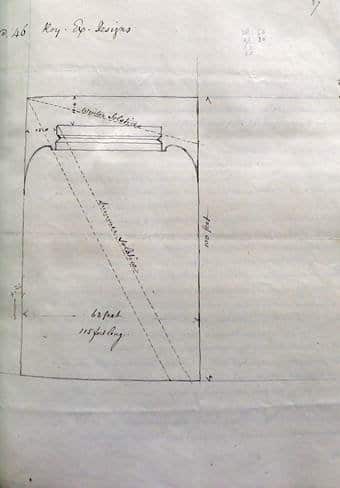

Gwilt believed Cockerell’s proposal to be ‘a design of great external architectural magnificence’. [3] Despite this magnificence, however, Gwilt noted that due to the height of the building and the size of the roof light, ‘no more than 2/3 of the Court[yard] could be treated with Sun’s Ray’. [4] In order to calculate this, Gwilt produced a small cross section of the courtyard. Drawn with a rough and inconsistent pen, this drawing is a proof in the pursuit of truth. In proportion if not to scale, Gwilt has measured out the dimensions of Cockerell’s proposed building before plotting the angle of the sun during winter and summer solstices. [5] Unlike Cockerell’s drawing, which offers an idea of the space rather than an empirical depiction, Gwilt’s section is analytical, abstract, and critical. There is a conversation occurring between Cockerell and Gwilt’s drawing. At the very least the later is questioning the former. But the language they’re speaking is not the same. And like language itself, there is ambiguity in Cockerell’s vision, which attempts to loosen the viewer from the precise literalness of drawing.

Notes

1. Mercers’ Company, Gresham Committee, minute of meeting held on 26 March 1839.

2. London Metropolitan Archives (LMA), CLC/521/MS04952, Papers relating to the Royal Exchange (‘Gwilt Papers’), f. 12.

3. LMA, ‘Gwilt Papers’, Report of the Judges, 9 October 1839, f. 2.

4. LMA, ‘Gwilt Papers’, 28 September 1839, f. 17.

5. LMA, ‘Gwilt Papers’, undated drawing, f. 27.

– Celina Fox