Writing Prize 2020: Hugh Casson’s ‘Diary’

Hugh Casson did it in the car. He did in in the Opera House, in Westminster Abbey and at the Buckingham Palace Garden Party. He did it in Goa, Mykonos and at Loughborough University. Wherever he went, whatever he saw, he drew. He drew to keep his eyes keen and fingers nimble. A thumbnail here, a doodle there. A squiggled cornice, a rushed-job portico, a façade abandoned because it had started to rain. On finer days, he lifted the lid on his watercolour box. Turning the pages of his swift-nib studies, you share his delight in every ogee, every onion dome, every oriel window, you feel the spill and thrill of brush and sponge. Sitting in dull selection meetings or on duller committees, Casson scratched the inky itch. Out came a surreptitious pen. A quick scribble in the corner, a lightning sketch in the margin. At prize judgings, he catches his fellow panellists poring over drawings, debating, deciding, perhaps dozing off, weary of the whole gold, silver and bronze medal business.

Above all, Casson drew because to draw was a pleasure. ‘A couple of short meetings,’ he wrote in his diary for Tuesday 22 January 1980, ‘the rest of the day at the drawing board.’ On Wednesday 23 January: ‘Miraculously, the same as yesterday.’ On Sunday 8 June: ‘Lovely day to myself at the drawing board. Funny how guilty one feels about feeling buoyant.’ On Tuesday 23 December: ‘Spent all afternoon drawing my local parish church for a charity auction.’ His diary is full of such entries, though not perhaps as full as Casson would have wished. A day without drawing was a day wasted.

On Friday 2 January 2016, I bought a second-hand copy of Hugh Casson’s Diary at Brixton Bookmongers. I know the date because I wrote it in my diary. Diarists are nosy about other diarists. Are they more or less assiduous? Do they ever skip or miss a day? In 1980, Casson – strictly: Sir Hugh – was 70 and entering his fourth year as President of the Royal Academy. In his preface, he notes that ‘a diary is seldom literature.’ In his case, the diary is something different: a work of art. Every day, every page is illustrated. His snapshot sketches of courtyards, interiors and streets are amused and unprecious. The Hounslow Public Library is as worthy a subject as Somerset House.

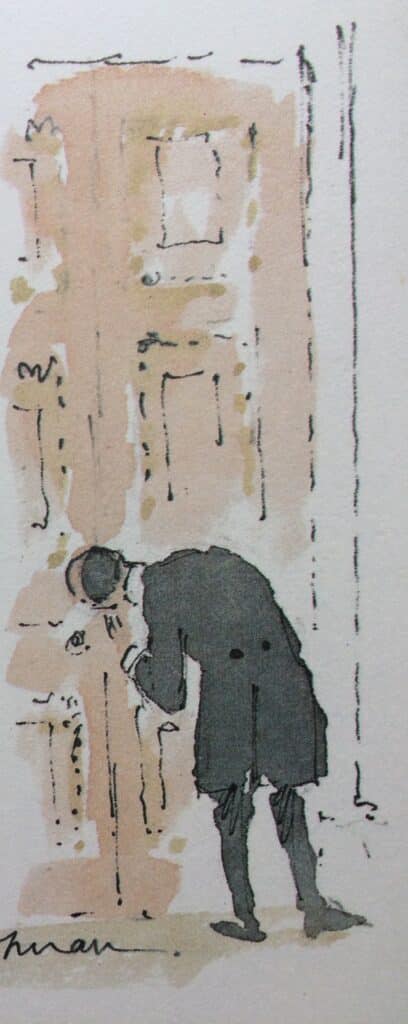

At Hartlebury Castle, home of the Bishop of Worcester, Casson draws the sweep of the staircase in the Great Hall, and at its foot, a corgi, tail turned to the artist. He draws with a giddy, infectious interest in people (and pets) as they move through buildings. He has his recurring favourites: the corridor loiterer, the gallery handyman in cross-backed suspenders, the stoutish matron in an up-to-Town hat. So as not to be noticed, he often draws from behind. Waiting for his annual audience with Her Majesty the Queen, he spots a footman, bending at the tail-coated waist to squint through a keyhole to assess royal progress. The panelling, the too-tall doors, the tiny handles spring instantly to life.

At Phaestos in Greece, he captures the broad-bottomed tourists, in sunhats and slacks, trudging a flight of ruined steps. Casson, who at 5ft 4inches would draw his own caricature waving from the top of a towering plinth, often sketched from the bottom of a staircase looking up. Seeing Death of a Salesman at the National Theatre, Casson, a former journalist and witty critic, reports: ‘As usual get lost in the foyer, where the staircases follow you about in a funny way.’

He got around town in his Mini. From home, to Burlington House, to his architectural practice in a Kensington mews. The only thing better than a morning’s drawing was a morning with partners and colleagues arguing around the office drawing boards. Casson is not grand. He accepts commissions for postage stamps and for fantasy stage-flats for the opera at Glyndebourne. There is his banqueting work (Royal Academy, Buckingham Palace) and his bread-and-butter work (Sainsbury’s in Chichester, Waitrose’s Beaconsfield store.) A request comes in for a doll’s house. ‘Oh well…’ Casson sighs. Work is work and dolls need houses too. His clients didn’t have to be human. Casson’s best-known building remains the Elephant House at London Zoo. He worried, though, about buildings that died on the board. Travelling to the newly opened Sainsbury Centre outside Norwich, he feared the gallery ‘will not inspire painters to paint its portrait. Here all the creative juices have already been drawn off in its creation.’

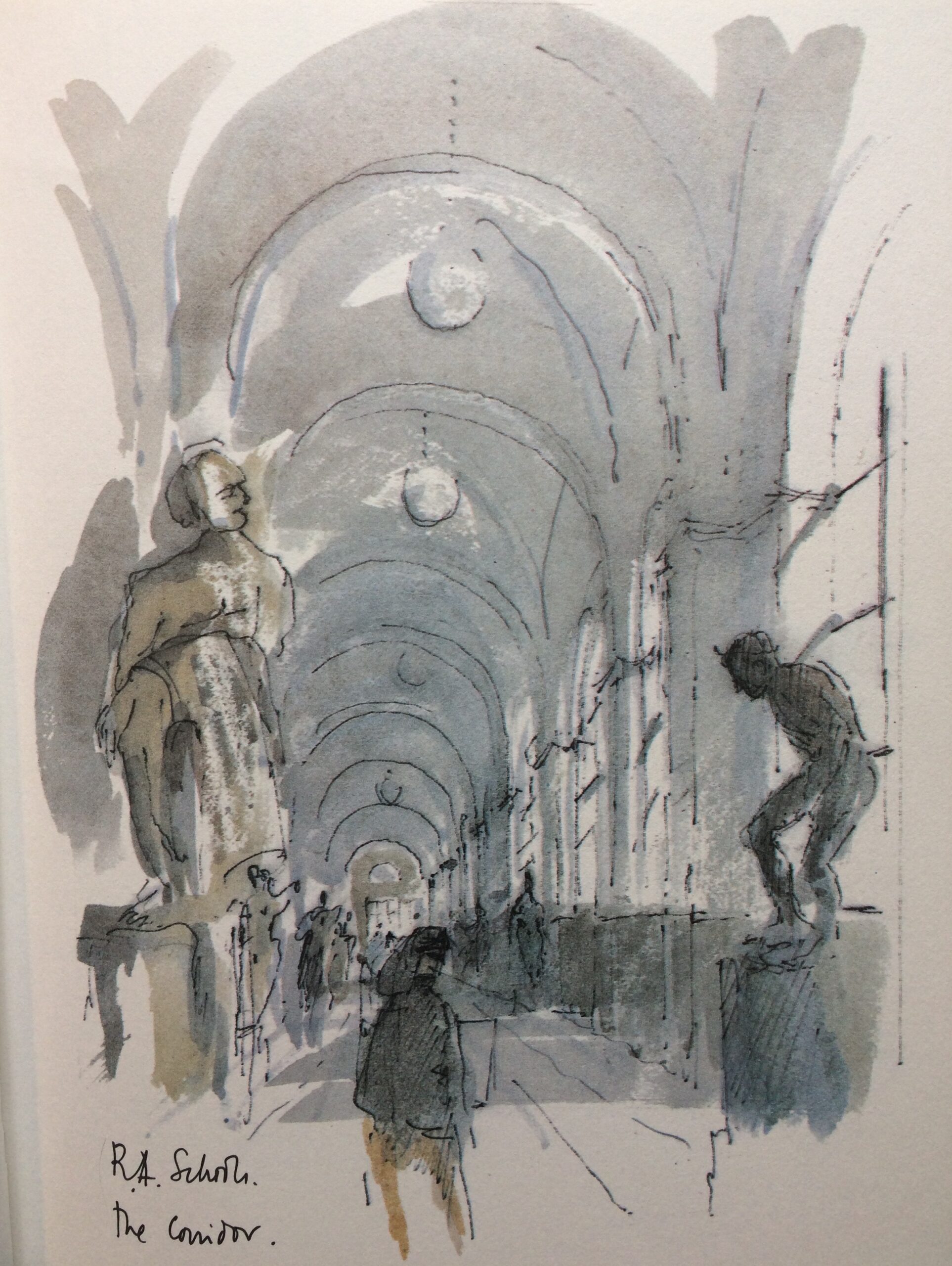

Arriving at Burlington House, Casson would leave the car in the ‘Presidential car-perk’ in the courtyard. He felt a proprietorial pride in the place. Finding long queues for an exhibition, he gives himself a ‘secret self-hug.’ Noticing a young woman breast-feeding her baby while eating smoked trout in the RA restaurant he writes: ‘Hooray! Could you do this at the Tate?’ In meetings his mind wanders, his fingers twitch for his pen. He never solved the problem, often discussed in ‘some despair’ with Architect Members of ‘‘exhibiting’ architecture as pictures on a wall.’ What keeps the RA kicking is ‘the nursery wing – the Schools and students.’ Visiting the Life Room, he draws the drawers themselves. Drawing mattered. Drawing came first and last and every point in between. At a summer lunch, he sits next to the 18-year-old daughter of a fellow guest, studying art and art history at Marlborough College, where, he notes, ‘the art master was nice enough to teach them to draw and not insist on instant self-expression.’

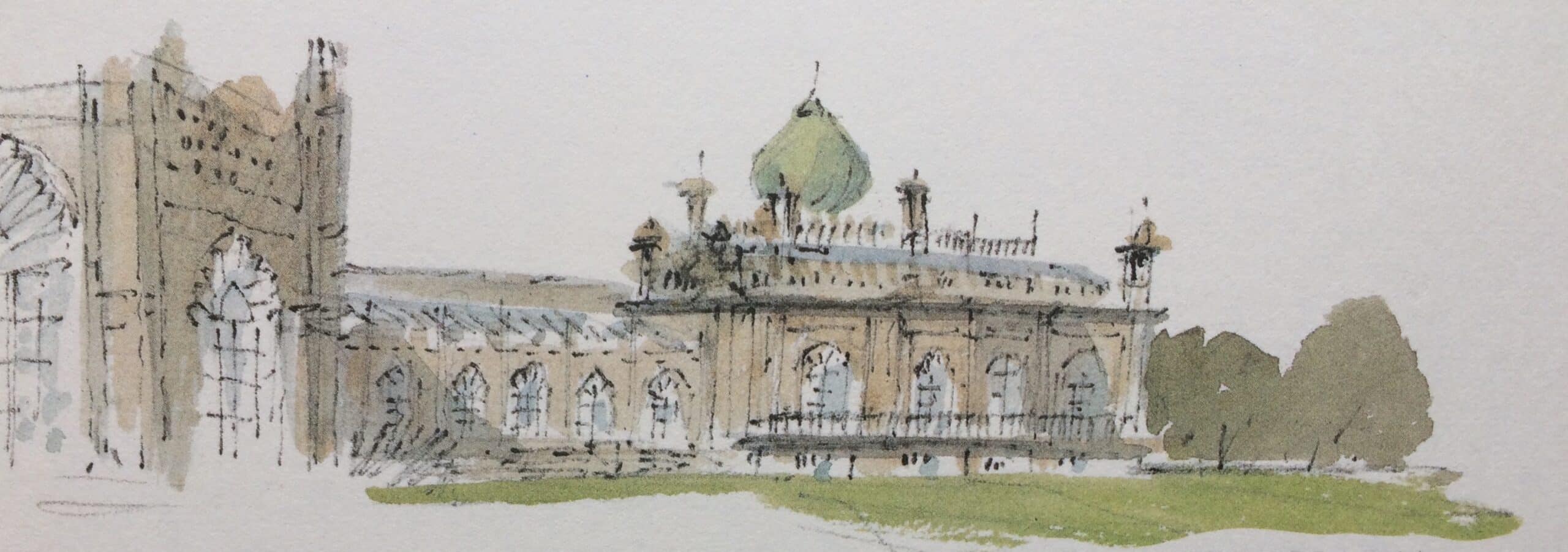

A perfect Casson day was something like the one he spent on Saturday 2 February at Sezincote, a Mughal palace in the Gloucestershire Cotswolds: ‘a knock-out even under scaffolding.’ He set up his stool on the lawn and was transported. He saw Sezincote ‘sunning itself as if in Ootacamund and waiting for the pith-helmeted, pony-mounted Raj-tots to return with the syces. A lovely day from beginning to end.’

Sun was best, but Casson was no fair-weather sketcher. Motoring to Windsor in December to draw Frogmore Cottage for the Queen’s Christmas Card, he did what he could with freezing fingers. There is an urgency about the sketch. Quick, quick, get it done, get indoors. If it was too cold to leave the Mini, he would sketch (to his shame) with the engine running. It gave ‘a very seductive trembly line.’ In the stalls at Covent Garden he made himself miserable trying to draw in the dark. Mikhail Baryshnikov may have been dancing, but Casson had only eyes for the set. He was modest, disciplined, often dissatisfied. All day at the drawing board and what did he have to show for it? ‘Mostly failures and discarded; a lifelong struggle continues.’

At times, he felt his age. ‘Weren’t you Hugh Casson?’ a former student asks. A young woman coming to interview him for her thesis on ‘professional design attitudes’ makes him feel like a ‘coelacanth’. Looking, sketching, thinking and inking kept him young. When the wind wasn’t numbing his fingers, when the mood, the light and the line were just right, then drawing became, in all its watercolour glory, a sort of sketchbook ecstasy.

Laura Freeman is writing a biography Ways of Life: Jim Ede and the Kettle’s Yard Artists to be published by Jonathan Cape.

This text was a prize winner in the long form category (1000–1500 words) of the Drawing Matter Writing Prize 2020.