James Gowan: Inside the Sketchbook

While typically, the architect employs the sketchbook as a raft by which to navigate the relentless flow of day-to-day practice, those that James Gowan assembled, across the course of his long professional life, served as a more elevated and leisurely mode of transport. Questions that he was addressing in the office at the time of their production certainly leave their mark, albeit in the form of immaculately resolved drawings, produced on a variety of paper stocks and pasted in. But the pages of these small volumes are also amply populated by memories and speculations of no clear immediate application.

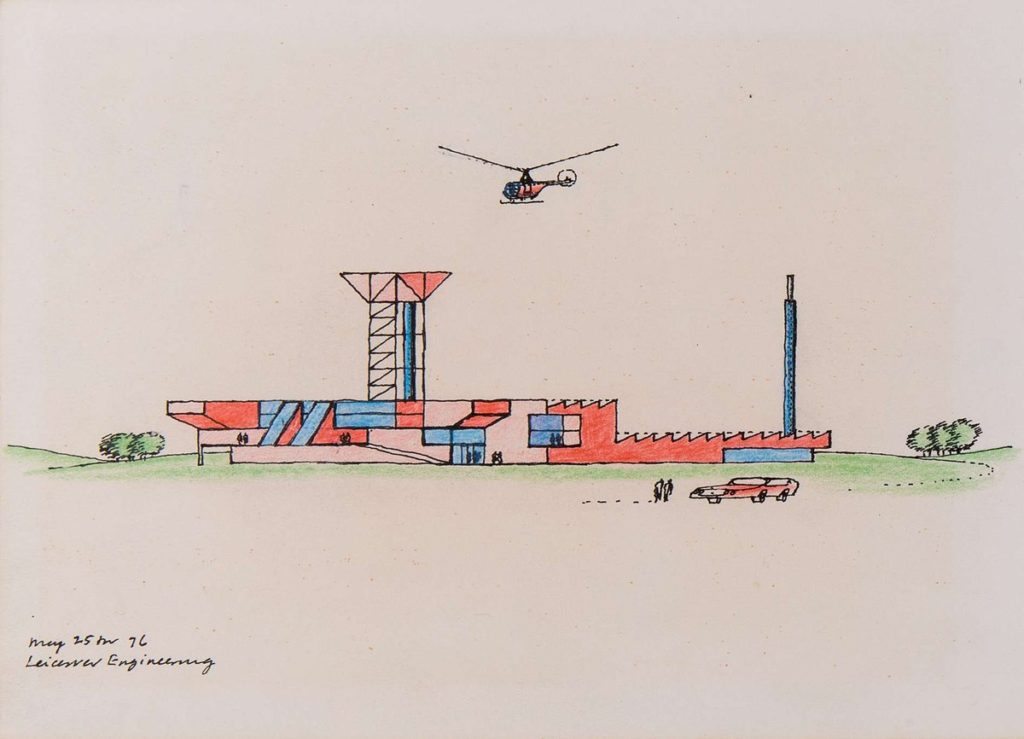

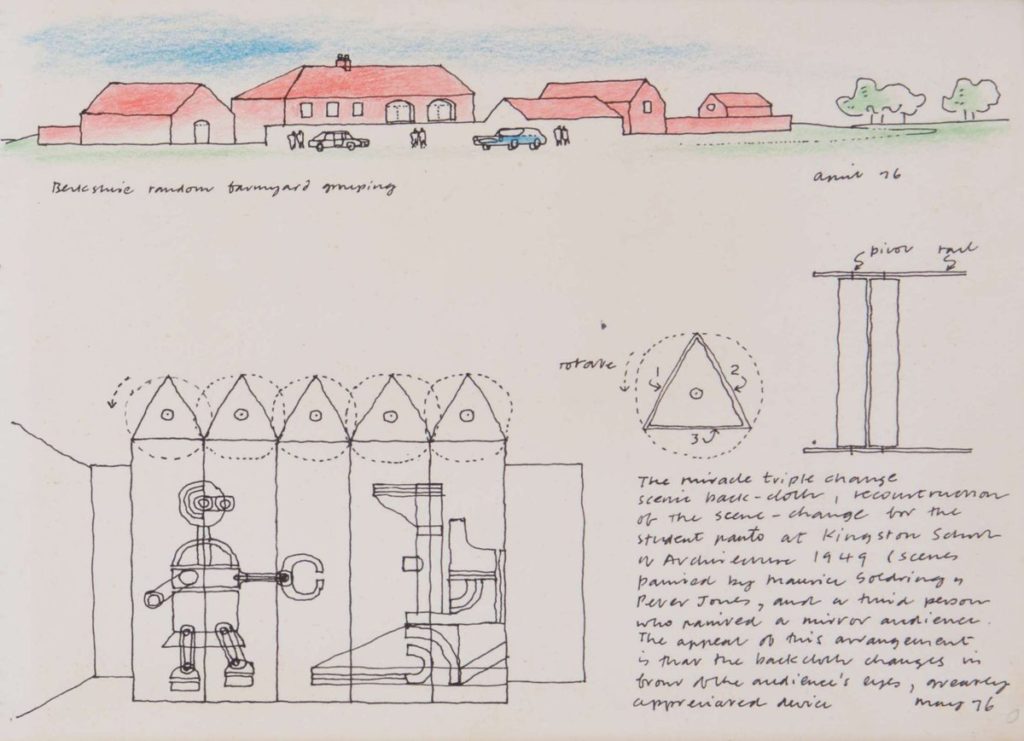

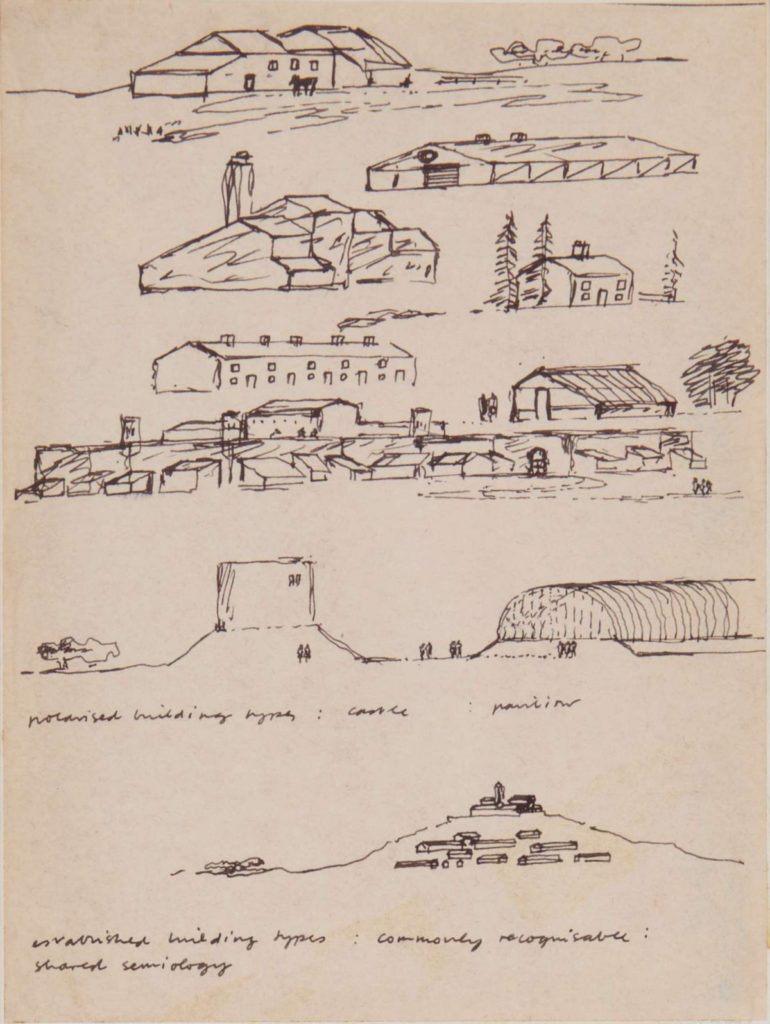

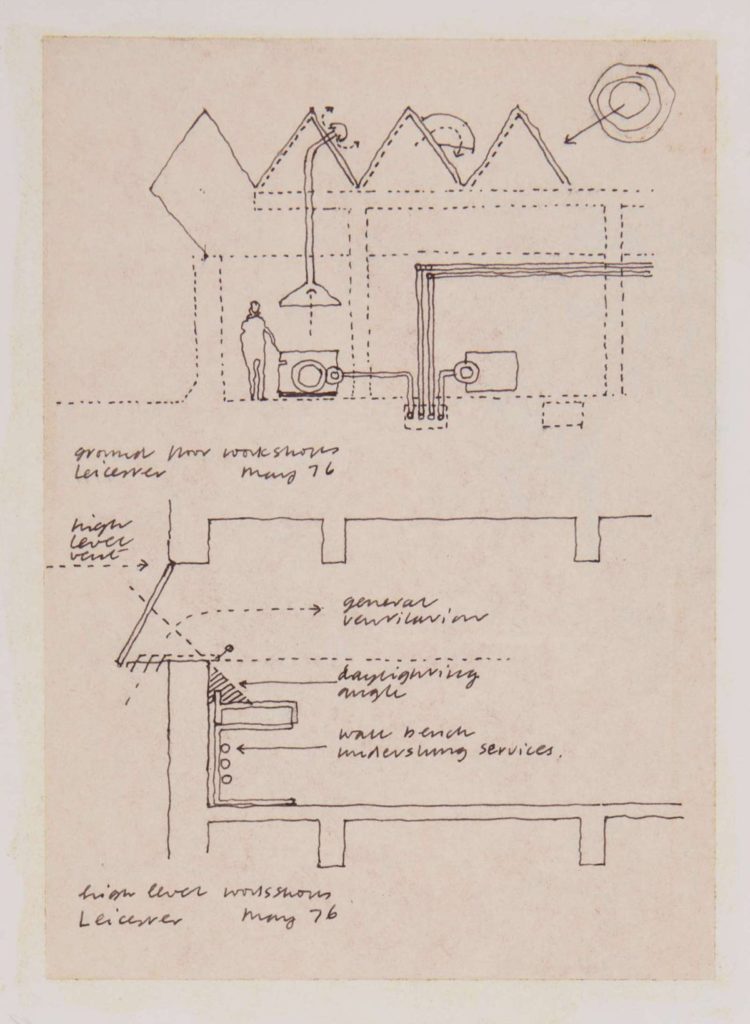

The ingenious set of a sci-fi themed student-skit, designed when its author was enrolled at the University of Kingston in the 1940s, finally finds a record thirty years after the event. More intriguing still are the many post-facto revisions of the Leicester Engineering Department, the potential loss of its spectacular but functionally suspect tower being a subject of particularly extensive enquiry. Elsewhere, we encounter elaborate structures of enormous scale – usually signalled by the appearance of a helicopter or Alpha Romeo – but no clear programmatic imperative. Pragmatic and fantastical explorations jostle for space on the same page, conveying both James’s absolute command of the technical aspects of his discipline and a readiness to pursue an idea solely for its graphic appeal. Like his hero, Marcel Duchamp, he maintained a conviction that the creative process necessitated an openness to both the rational and irrational parts of the mind. In his sketchbooks those sources intersect in ways that are constantly surprising and provocative, as they no doubt were to him.