Aldo van Eyck: Diruit, aedificat, mutat quadrata rotundis

‘He pulls down, he builds up, he exchanges square for round.‘

Horace—Epistles. I. 1. 100[1]

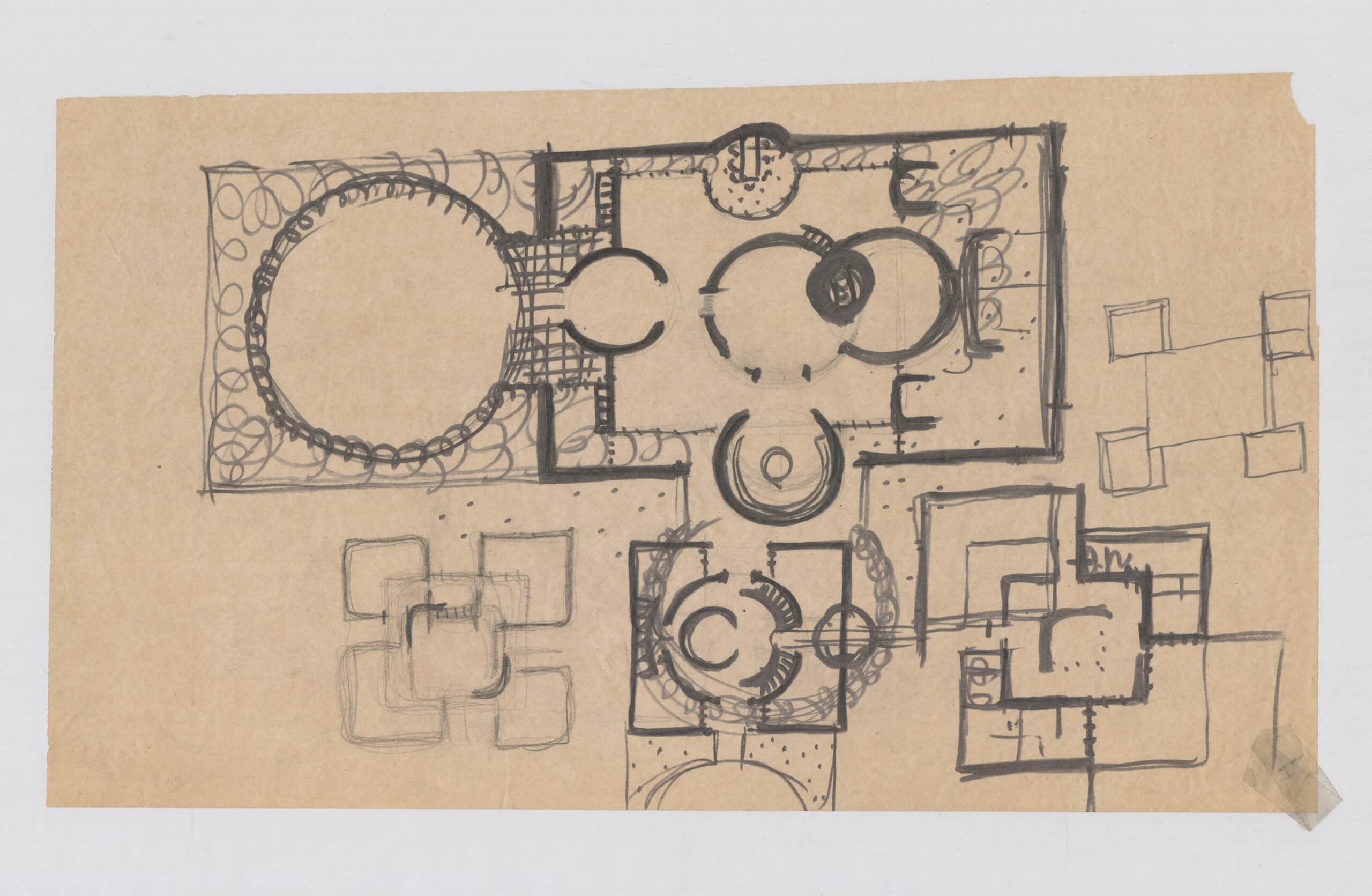

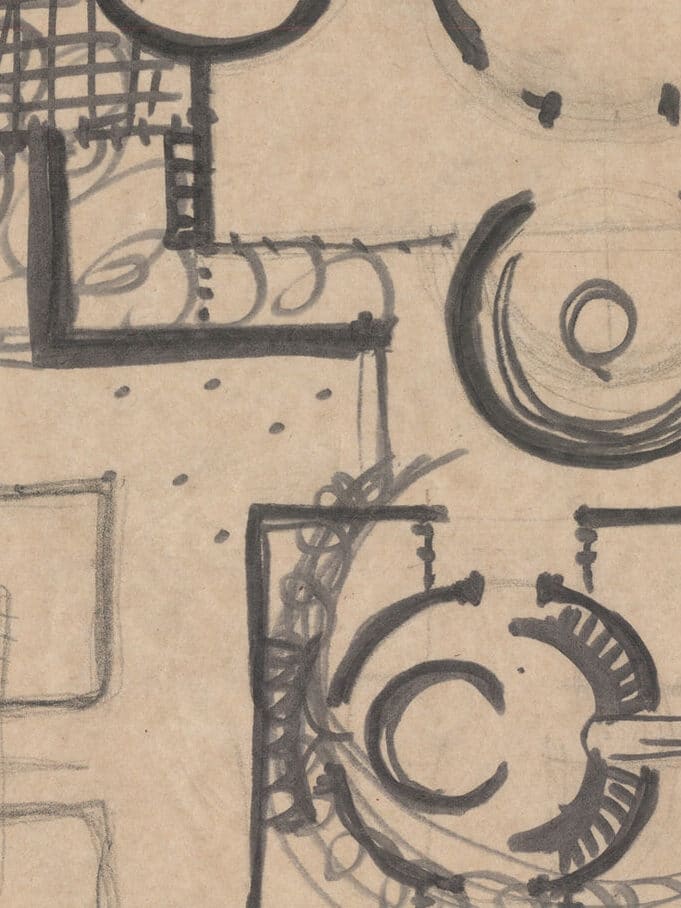

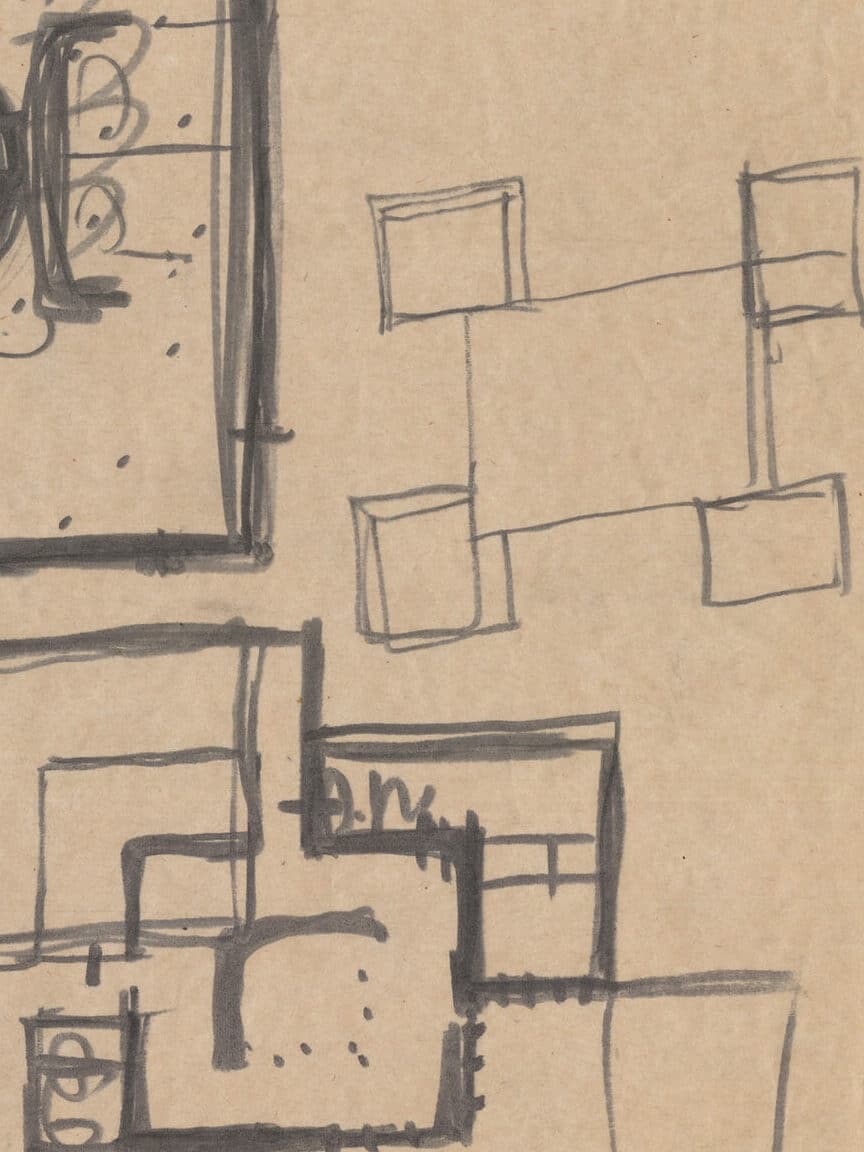

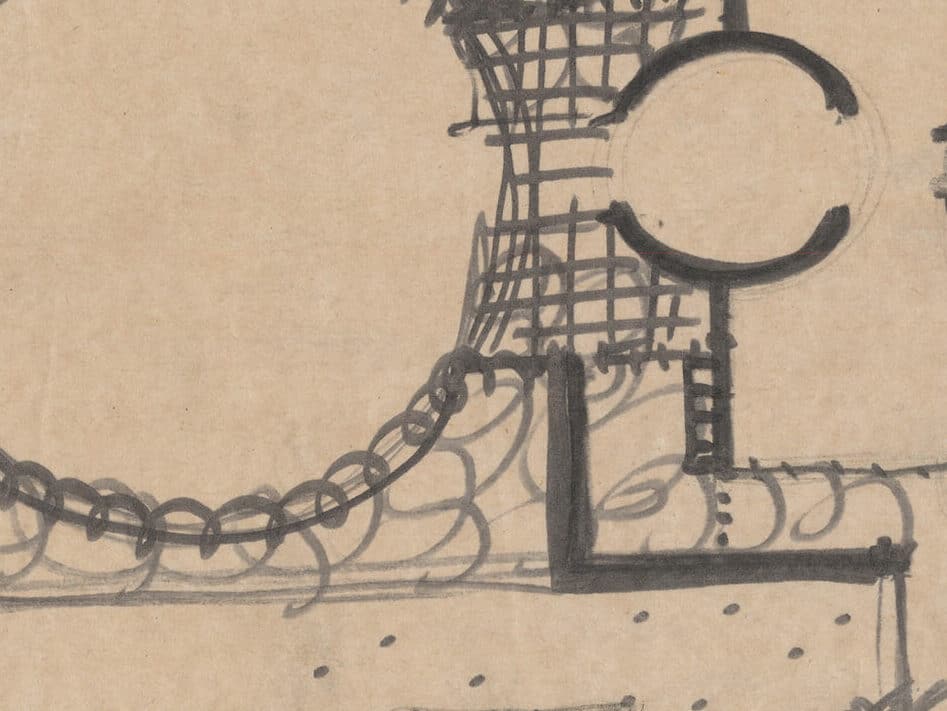

The Aldo van Eyck drawing currently on show at 13 Lincoln’s Inn Fields appears, at first glance, to do precisely this. A preliminary drawing, one made for the design of the architect’s own house, on transparent paper. Ripped from a roll, corners taped and torn, suggest that this drawing is an overlay, a working over, a working out. It shows a traced and altered plan, roughly to scale, and around it a constellation of emergent ideas, sequentially revealed. This drawing has been returned to at least three times, in distinct media, rotated, reformulated and reconsidered. In each case it pulls down, it builds up, it exchanges square for round.

‘I trust it is not necessary for me to caution the students further from being led astray by authorities, however great, to the adoption of such false taste. Such ineffectual attempts at contrast and variety must be fatal to every sound principle of good architecture. Without descending to unjustifiable innovation the artist will have sufficient opportunities to display the richness of his fancy, the fertility of his invention… the plan will furnish him with innumerable occasions of showing his knowledge of ingenious combination and convenient distribution.’

—John Soane, Royal Academy Lectures[2]

Soane sought an architecture with capacity to move the soul, but to do so moderately, Notions of propriety, taste and judgement formed the performative kernel of his Royal Academy lectures whose aim was to form, to instruct, to point out and to fit students for their own critical examination.[3] On surface value, Soane may have questioned Van Eyck. On review, Soane may be seen to share some similar concerns, attentive to precedent, engaged with posterity, alert to difficulty and challenge. His task, in the lectures, is to set out and to offer guidance on matters of distribution, construction and decoration, in part to inspire and in part to temper excess, correcting these urges with:

‘Nice distinctions… nice discriminations… and nicest particulars.’

—John Soane, Royal Academy Lectures[4]

But what is nice?

Nice is hardly a virtue, but sits in the domain of aesthetic judgement, a word which mediates between internal conjecture and external reception. Nice is careful. Nice is cagey. Nice recognises its critical edge, but for the sake of propriety, sacrifices honesty for discretion. Nice stands in for something else, it is always a proxy.

‘I am sure,’ cried Catherine, ‘I did not mean to say anything wrong; but it is …nice, and why should I not call it so?’

‘Very true’ says Henry, ‘and this is a very nice day, and we are taking a very nice walk, and you are two very nice young ladies. Oh, it is a very nice word, indeed! – it does for everything.’[5]

Published in 1817, but written earlier, Jane Austen’s Northanger Abbey parodies the polite society in which Soane moved. Henry, or rather Jane, is goading, probing, aching for her heroine to simply say what she thinks. ‘Nice’, used in this fashion, has a satisfying sibilance, a trailing hiss that catches and provokes. To be ‘nice’ or to deem something ‘nice’ masks, to some degree, an unresolved feeling of doubt, or uncertainty, something that (otherwise phrased) might drive one to distraction. To say that something is ‘nice’ one might be said to secure or defend a certain distance between what is said and what is really felt. To be ‘nice’ might buy time, it might also beckon, cajole or sting. In a way, ’nice’ exists in service of others, a self-sacrificial banality, which might also be considered a tease or an armour.

Animals hiss when they are frightened, or in order to attract attention. In some ways being ‘nice’ acts also to avoid attention, a fricative sound-object or pragmatic noise which marks hesitation, occurring at interactional or relational trouble spots, delaying the progression of a thought while allowing the speaker to initiate or maintain their turn.[6]

‘She knew nothing of drawing—nothing of taste.’

—Jane Austen, Northanger Abbey[7]

A Nice Drawing?

The drawing here can hardly be said to be nice, let’s be honest for a moment. It is scratchy, imprecise, multiple. Hedgerows are drawn fruitily, patios irregular, lawns patchy. What is at stake is not precision, but articulation. Van Eyck seeks something in this drawing, something which evades him. He wants to tell us about it, but he doesn’t yet quite know how.

According to Michel Chaouli, criticism involves three moments: ‘something speaks to me, I must tell you about it, but I don’t know how.’[8] Van Eyck’s drawing, then, can be seen as nothing other than critical: the ultimate goal of the Academy Lectures, an intentional, concentrated hunt for an idea which continuously withdraws from the imagination’s easy reach, moving beyond sight, beyond grasp. And yet the movements of the pen record the value of such effort, an irritant principle which teases and cajoles, which leads us on. A kind of flirtation, this drawing both pursues and spurns the ‘nice’. It makes demands.

Relating to difficulty, hierarchy and hesitation, between out breath and in, ‘nice’ is a strident shimmer, a signal of initiation or a sign of resignation. For Van Eyck, the metaphor of breathing was invoked in many guises, but always as an inclusive, discursive and self-effacing gesture to open up the discipline, to render it less abstract, more joyful. If these drawings can be said to be ‘nice’, it is that they too act as a kind of pragmatic pause, a means of transitioning between things, an articulation of difference.[9]

In his radical swapping out of circles for squares, the looping recalcitrant lines, Van Eyck’s drawing speaks less of a descent into ‘ineffectual… contrast and variety’ than a strident effort to strike at the heart of critical examination, an experience which advances intimacy, which builds capacity, which sanctions reflection.

It shows what it thinks. Nice.

Notes

- John Soane, ‘Lecture VIII’, in Sir John Soane: The Royal Academy Lectures, ed. by David Watkin (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2000), 187.

- Ibid, 187.

- ‘Lecture VII’, Watkin, op. cit, 156. ‘As set out in the regulations of the Academy.’

- ‘Lecture VII’, ‘Lecture XI’, ‘Lecture VIII’, Watkin, op. cit, 160, 255, 187.

- Jane Austen, Northanger Abbey (London: Penguin Classics, 1994), 96.

- Lucien Brown, et al. ‘Is It Polite to Hiss?: Nonverbal Sound Objects as Markers of (Im)Politeness in Korean.’ Frontiers in Communication, vol. 7, (2022), https://doi.org/10.3389/fcomm.2022.854066.

- Austen, op. cit, 99.

- Michel Chaouli, Something Speaks to Me: Where Criticism Begins (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2024).

- Articulation does not mean the ability to talk with authority […] but being affected by differences’ Bruno Latour notes in ‘How to Talk About the Body? The Normative Dimension of Science Studies’ Body & Society, vol. 10, no. 2–3, (2004), 210, https://doi.org/10.1177/1357034X04042943.

This drawing by Aldo Van Eyck from the Drawing Matter Collection is currently exhibited in Soane and Modernism: Make it New at Sir John Soane’s Museum.

Laura Harty is an architect and Director of Education at the Edinburgh School of Architecture and Landscape Architecture (ESALA), University of Edinburgh. In both roles she engages daily with drawing instruments and instrumental drawings, many of which stand their ground and show us the way. Living in Perthshire, Scotland, with a young family and a long commute, most of her drawing is on other’s shoulders.

– Manuel Montenegro, Helen Thomas and Ellis Woodman