Collection Guide: Andrea Branzi & Archizoom Associati

– Rosie Ellison-Balaam and Francesco Fiammenghi

To probe the long and multifaceted career of Andrea Branzi (1938–2023), one must first turn to his formative years at the Faculty of Architecture at the University of Florence in the early 1960s. At the time, the Florence School became the incubator of several of Italy’s postwar avant-garde groups, including Archizoom, which was co-founded in 1966 by Branzi, Massimo Morozzi, Gilberto Corretti, and Paolo Deganello, and later joined by Dario and Lucia Bartolini in 1968. In this heterogeneous generation of architects—the so-called ‘Radicals’—lay a common denominator: a critical stance toward the modern movement and the will to overcome disciplinary boundaries. Within this broader tendency, Archizoom pursued a distinctive agenda that, despite resisting straightforward definitions, was often encapsulated in their formula ‘city without architecture.’ In general terms, their most notable contributions rejected architecture as a discipline anchored in the autonomy of the architectural object, refocusing instead on the city as the critical subject of analysis and representation. Their theoretical and political projects aimed to move beyond ‘progressive,’ ameliorative utopian schemes, embracing and analytically decoding the consumer society in which they lived.

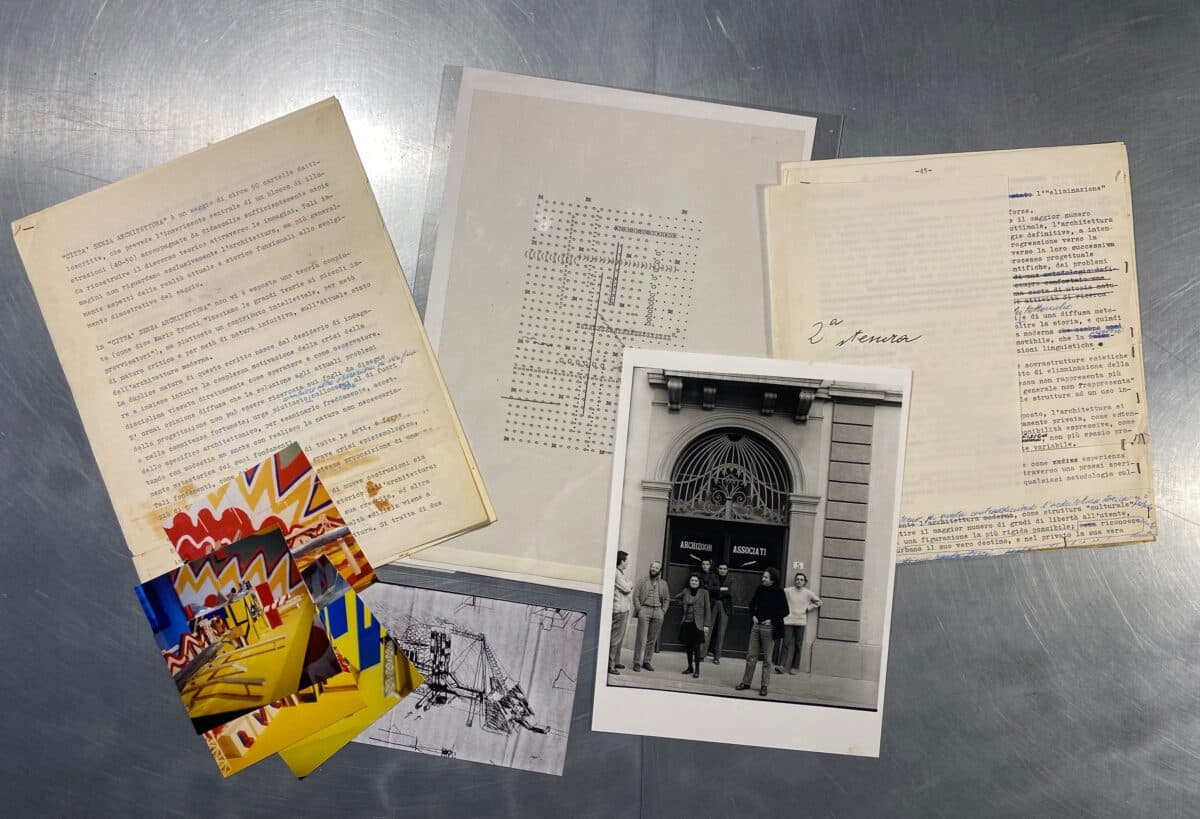

The materials held at Drawing Matter, acquired directly from Andrea Branzi’s studio, span primarily from 1966 to the 1980s, from the beginnings of Archizoom to Branzi’s later cultural production as a solo figure. The collective endeavours of Archizoom came to an end in 1973 with the group’s disbandment, yet those experiences proved foundational to Branzi’s subsequent career as architect, designer, educator, and—particularly relevant to Drawing Matter’s holdings—theorist and critic. Indeed, more than any of his Radical peers, he devoted his intellectual life to assessing the broad phenomenon and legacy of that peculiar generation of Italian architects formed in the 60s, a commitment reflected in the writings preserved in the collection. Branzi’s and Archizoom’s archives are kept today at the Centro Studi e Archivio della Communicazione Università degli Studi di Parma, at the Center Pompidou in Paris, and at the FRAC Center in Orléans, as well as spread between the group members’ personal archives.

READ ALL WRITINGS ON ANDREA BRANZI and ARCHIZOOM ASSOCIATI.

VIEW THE COMPLETE DRAWING MATTER COLLECTIONS OF ANDREA BRANZI AND ARCHIZOOM ASSOCIATI HERE.

PROJECTS

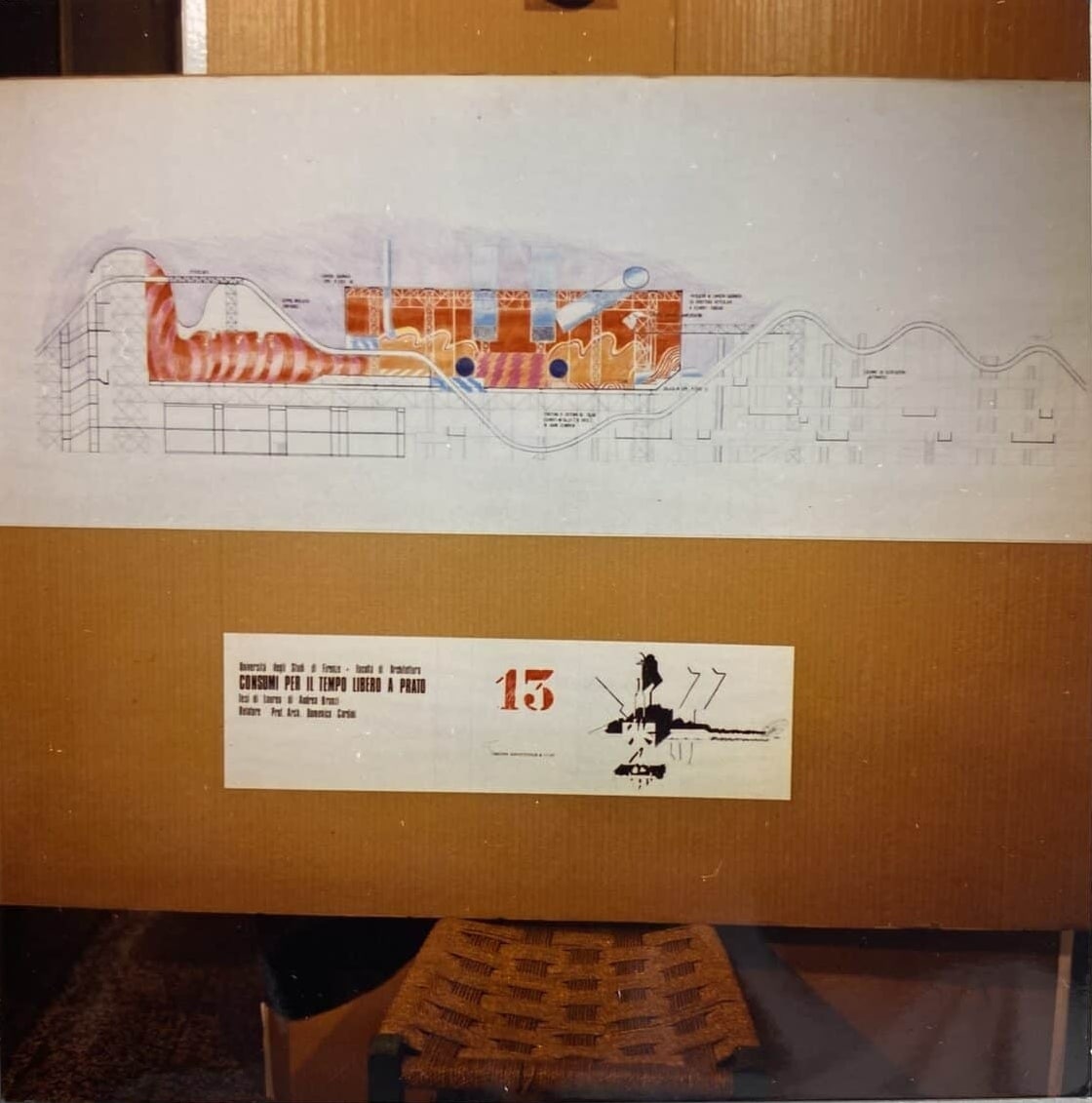

TESI DI LAUREA – CONSUMI PER IL TEMPO LIBERO A PRATO, 1966

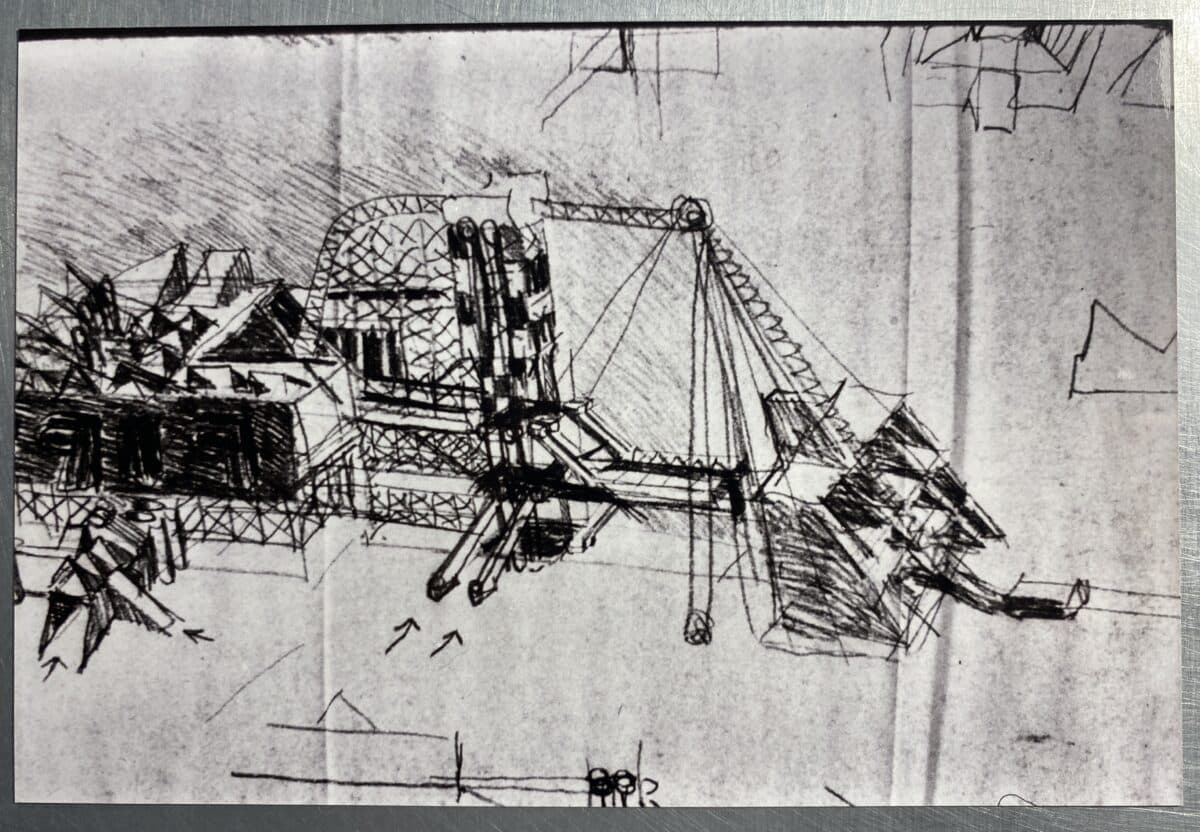

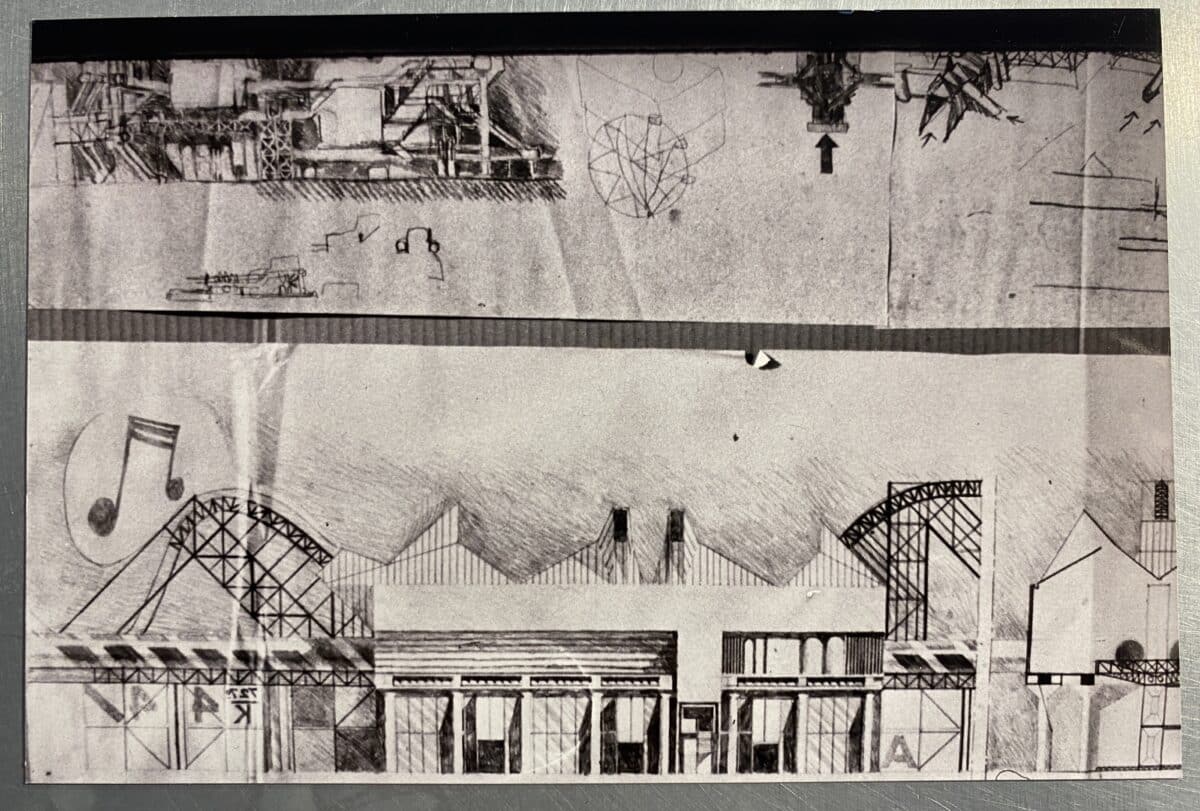

Andrea Branzi’s ‘Tesi di laurea’ (‘graduation thesis’), titled ‘Consumi per il tempo libero a Prato’ (‘Leisure consumption in Prato’), also known as ‘Free-time Facilities in Prato’ or ‘Permanent Luna Park’, was submitted to the Università di Firenze in July 1966 under the supervision of Professor Domenico Cardini. The project’s central theme was leisure time, conceived as ‘recovery time’ for a renewed way of living in opposition to ‘waged time.’ It formed part of a triptych of graduation theses at the University of Florence on the same topic, together with those of fellow Archizoom members, Gilberto Corretti and Paolo Deganello. At the time, the theme of leisure had recently entered the architectural discourse through the 1964 Triennale di Milano dedicated to ‘Tempo Libero’ (‘Leisure Time’).

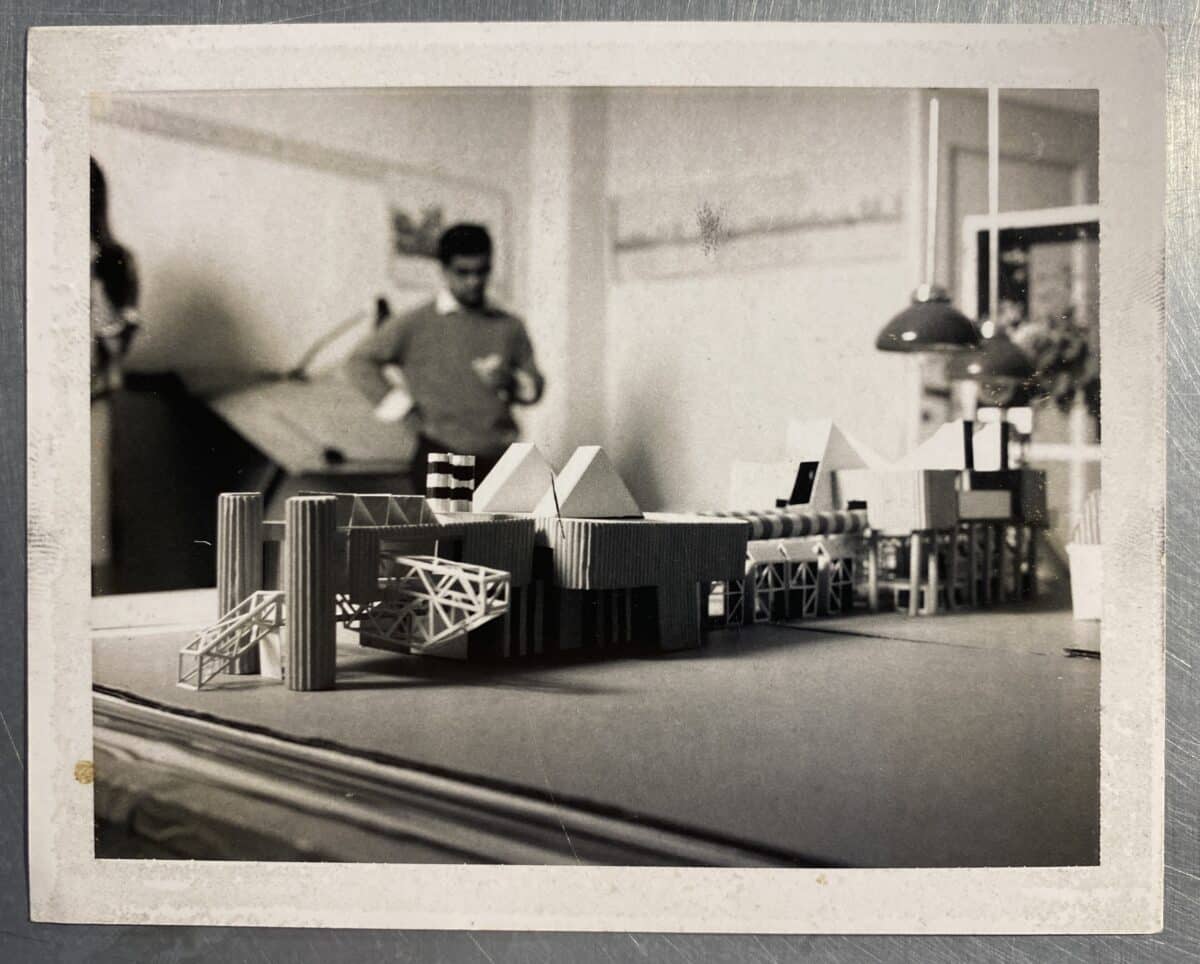

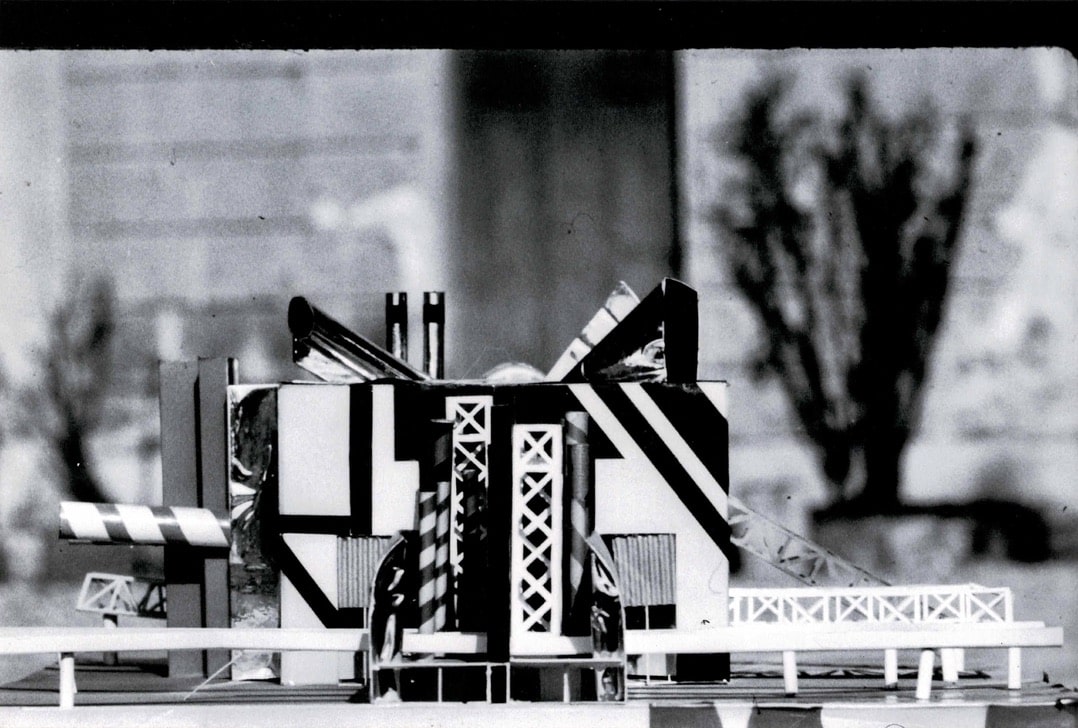

The site of the urban intervention is the periphery of the Tuscan city of Prato, which was subject to the sterile homogeneity of an industrial centre that ‘produces but does not consume.’ Branzi aimed to break through this urban impasse by designing a steel megastructure that accommodates a cluster of polyfunctional programmes to induce consumption: in Branzi’s words, ‘a fun machine’—in clear reference to Cedric Price’s ‘Fun Palace’ (1964). A key element is a roller-coaster that allows users to run through most of the building’s spaces, including a disco, gym, supermarket, cinema, and a tunnel of vending machines. With a realist approach, the project is characterised by a striking Pop figurality, fully embracing the aesthetics of consumer society in an anti-ideological way. This led to the exhibition of ‘Superarchitettura’ in the same year, further contextualising the intertwining between architecture and consumption.

In the collection are four sets of photographs of the project, divided by the negative slips that accompany them. One was developed at Bongi, L’ottico di fiducia, in Florence in 1966 (DMC 2738.3.1)—they are black-and-white photos of the model, including a process model, as well as shots of his presentation boards and sketches. The next set (DMC 2738.3.2) are black and white photos mainly of the model’s details. Another holds (DMC 2738.3.3) colour images of the project’s elevation drawings, also featured on his presentation boards. The last set (DMC 2738.3.4) are colour photos of the model against the background of a reproduction of Roy Lichtenstein’s Pop Art.

SUPERARCHITETTURA, 1966-67

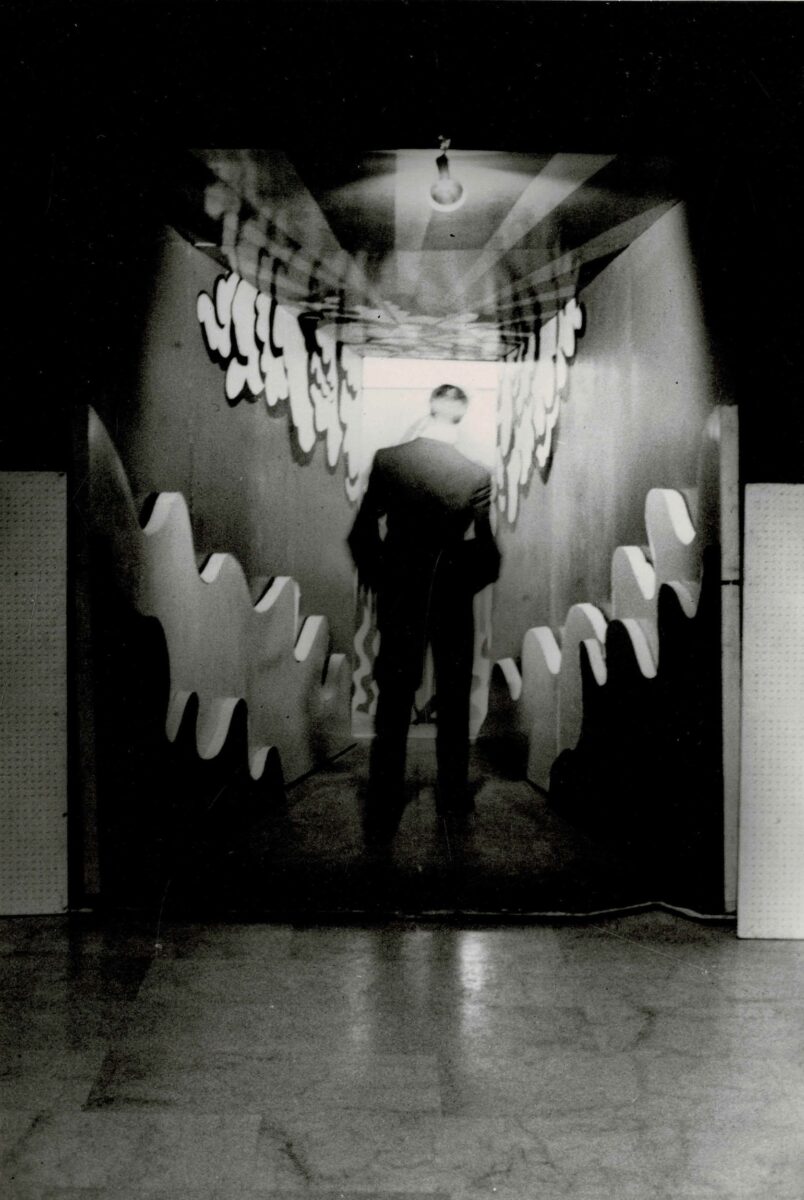

‘Superarchitettura’ was an exhibition by Archizoom and Superstudio that opened on December 4th 1966, at the Jolly 2 Gallery in Pistoia. This event coincided with their first public appearance as newly-founded collectives, united by the intent to showcase, embrace, and critique the excessive nature of consumerism, in which architecture, ironically exalted with the prefix ‘Super,’ is absorbed and ‘consumed’ by the unrestrained exuberance of the market itself. Originally, it was meant to open in Florence, but due to the flooding of the River Arno in November of that year, it was moved to Pistoia, where the ‘gallery’ was a cellar consisting of two rooms that belonged to a fish wholesaler. For the occasion, it was transformed into an immersive environment, furnished with a jumble of voluminous, loud, and colourful Pop artefacts, including early prototypes of Superstudio’s lamp ‘Passiflora’, and Archizoom’s sofa ‘Superonda.’ Apart from these anti-functional design objects, they also exhibited the graduation projects of Branzi, Morozzi, and Corretti, which strongly adopt Pop aesthetics. It is worth noting that, since then, Archizoom and Superstudio have often been debated and compared together, becoming the avant-garde reference in the broader historiography of post-war Italian architecture. The Drawing Matter collection holds photographic slides of the exhibition.

‘Superarchitettura’ was soon broadened into another exhibition by the same title, held from 19th March to 12th April 1967, at the Galleria Comunale in Modena. In this case, while maintaining the conceptual framework that prompted the Pistoia show, it also showcased several projects from the Faculty of Architecture in Florence, including those by Branzi, Corretti, Deganello, and Morozzi. These works openly embraced the ‘Superarchitettura’ manifesto, printed on the exhibition’s poster: ‘Superarchitecture accepts the logic of production and consumption, and works for its demystification’; it is an architecture made of images that possesses the same subversive power as advertising. Four black and white photographs capture the opening of the exhibition: visitors looking at Branzi’s ‘Tesi di laurea’ model, as well as a panel discussion in front of Morozzi’s ‘Centro Culturale dentro il Castello dell’Imperatore a Prato’ (1967), with, on the right, Superstudio’s Adolfo Natalini’s ‘Palazzo dell’Arte di Firenze’ (1966)—both graduation projects.

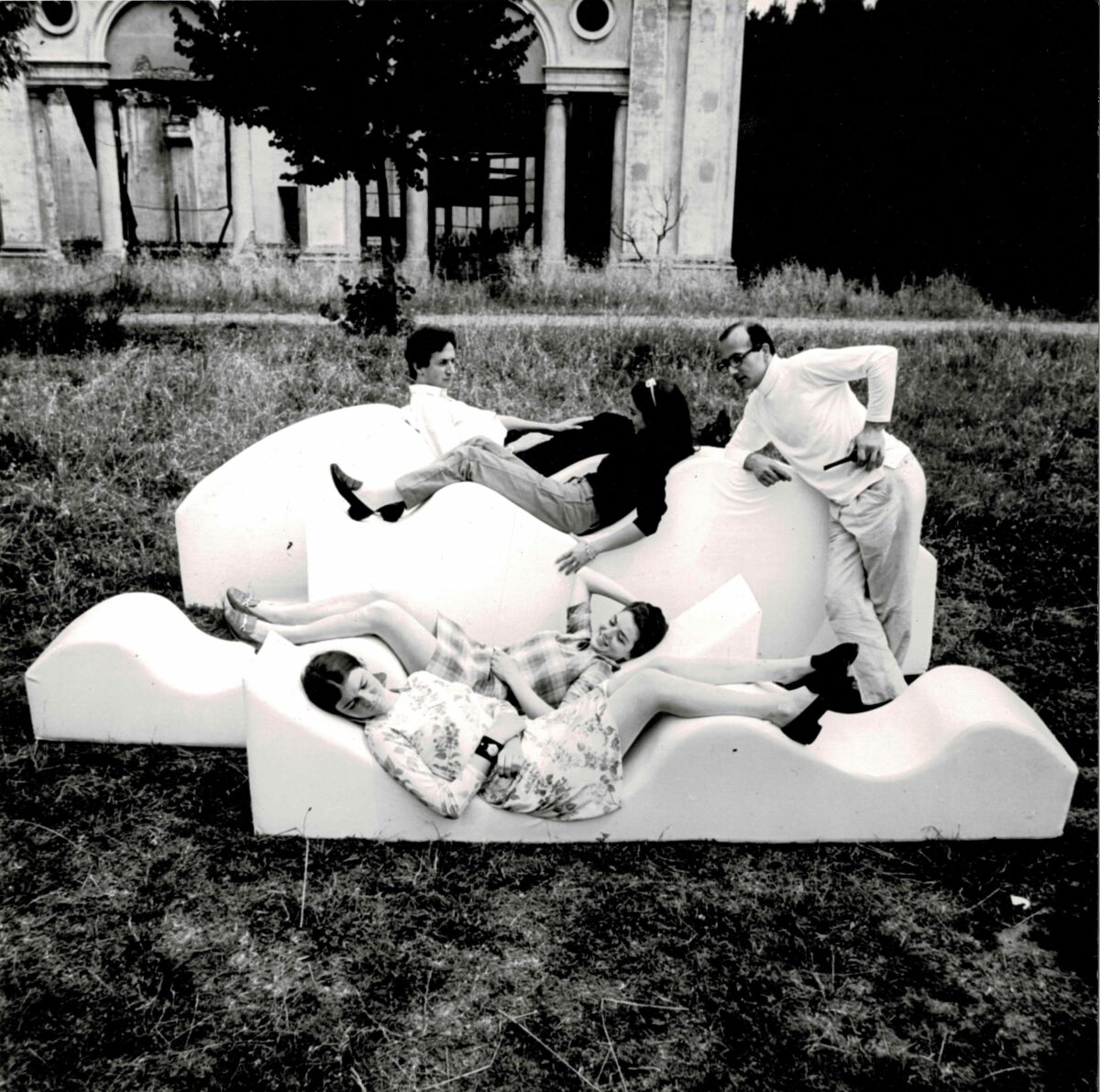

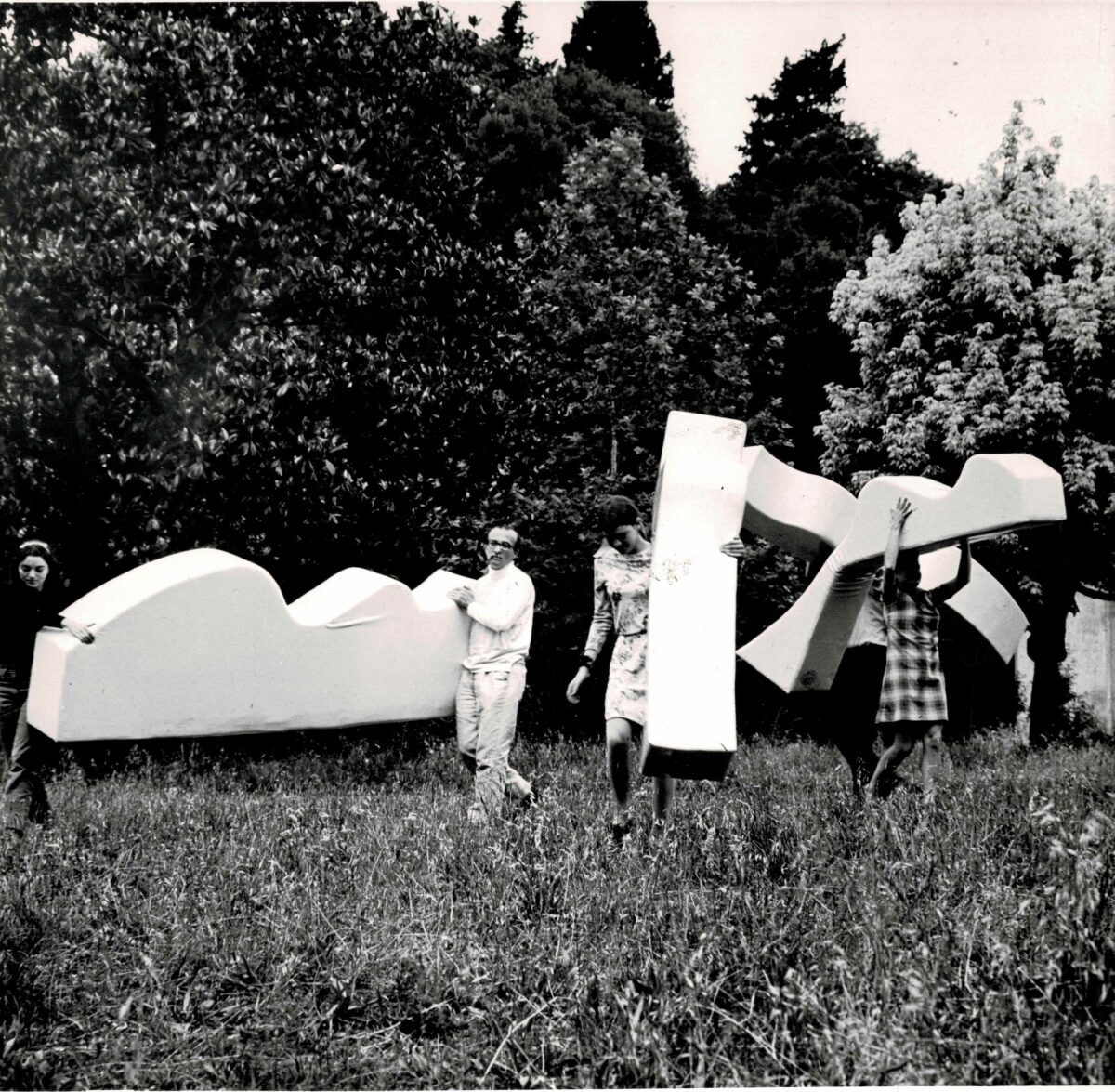

SUPERONDA SOFA, 1966

A prototype for the Superonda was displayed as part of the ‘Superarchitettura’ exhibition: an undulating sofa with a contrasting stripe pattern. At its presentation in Pistoia, the sofa attracted the attention of Sergio Cammilli, owner of the furniture company Poltronova, who put their design into production. The sofa is without a frame, made from polyurethane coated in leather, a single rectangular block cut with a snaking ‘s’ shape, this irregular cut allowing for many configurations. It was designed to accommodate unconventional positions, for both object and user; whether placed together or apart—the sofa created new ways of sitting. It was presented first at the VII Salone del Mobile, Milan in 1967, available in red, black, or white. It is the first of numerous collaborations between Archizoom and Poltronova between 1966 and 1973. Drawing Matter holds two photographs of Archizoom with their sofa, taken in the grounds of their first studio at Villa Strozzi in Florence.

It is also of note that through the Superonda, Archizoom met the designer Ettore Sottsass Jr., who had joined Poltronova in 1957, a figure who they would go on to collaborate with on many other projects. Sottsass recounts his first interactions and impressions of Archizoom in his article, ‘Gli Archizoom’, for Domus n.455 (1967).

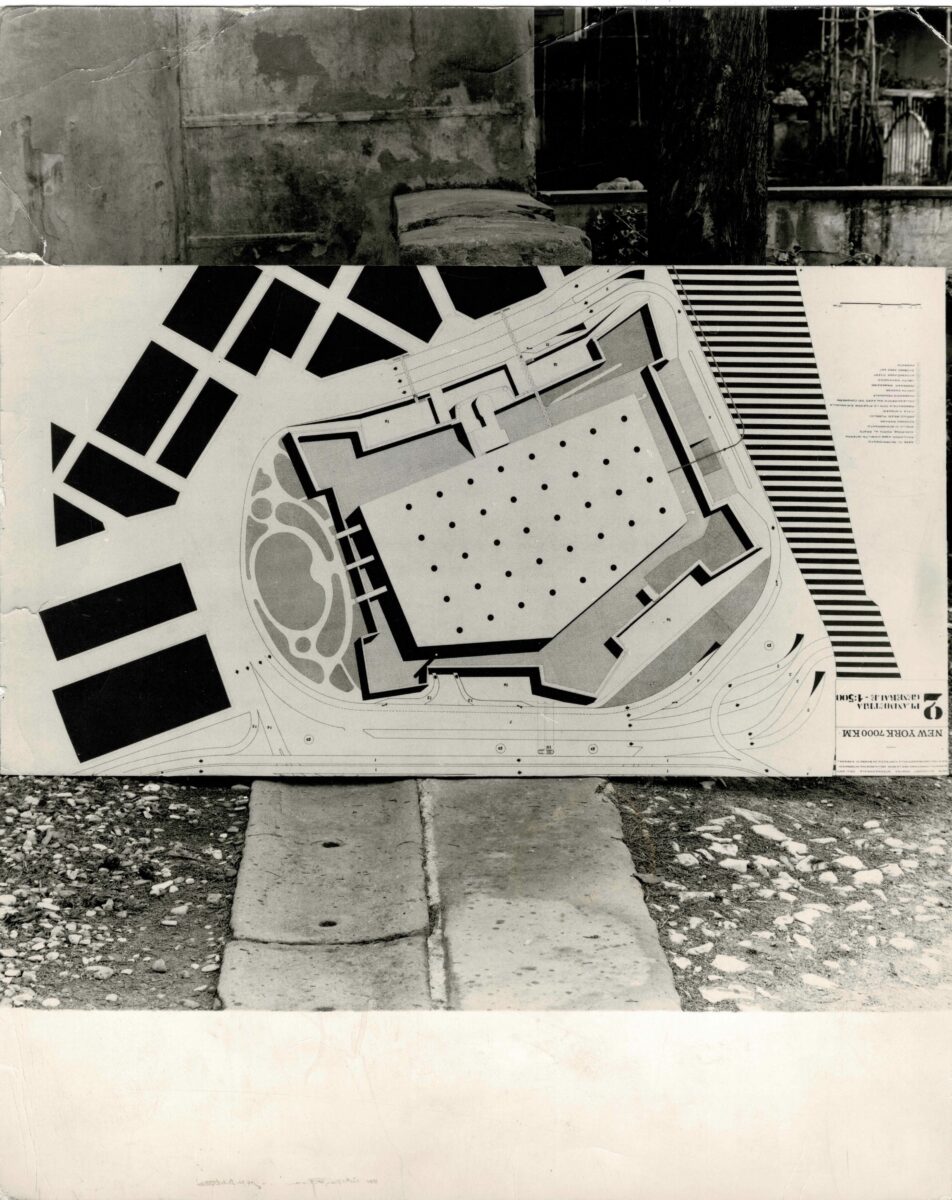

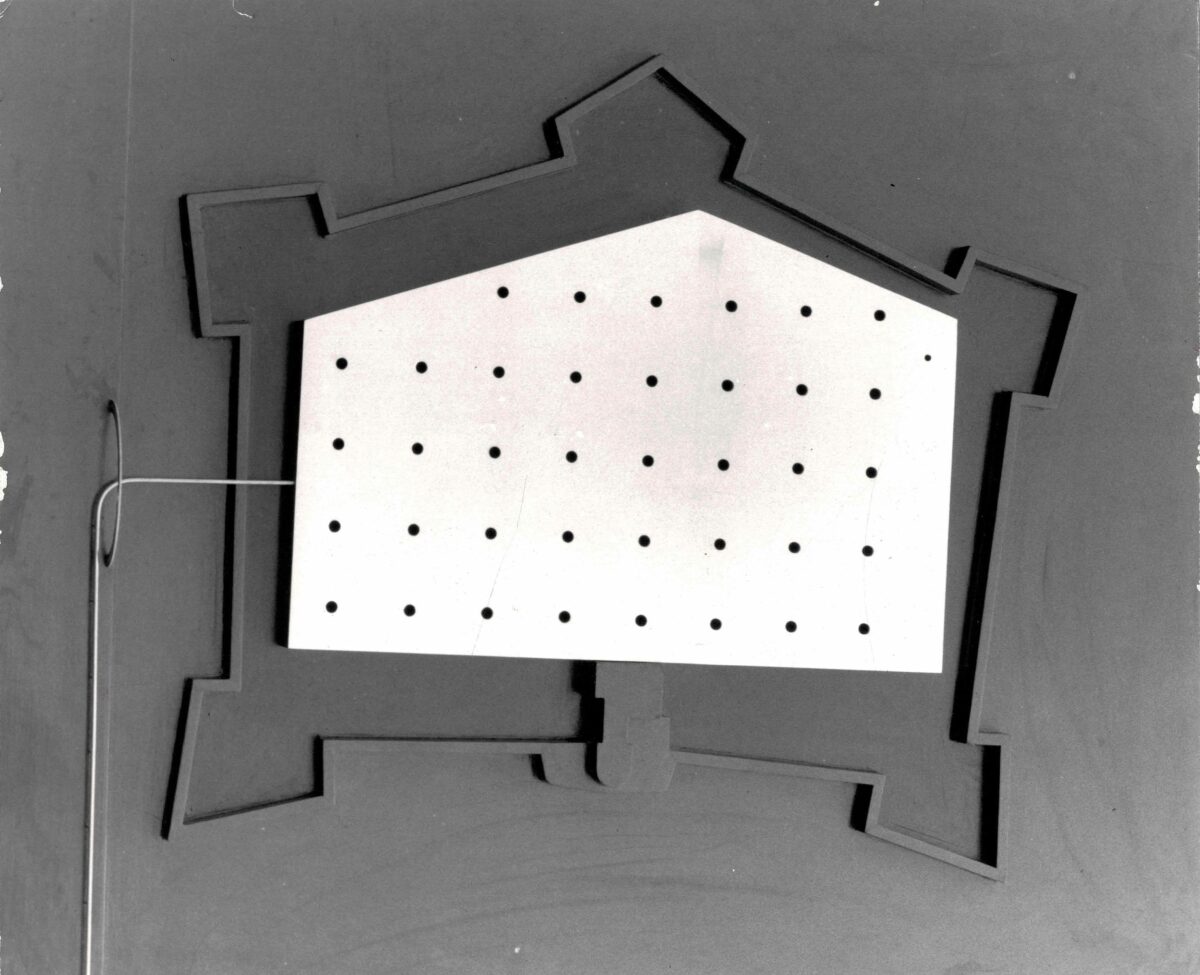

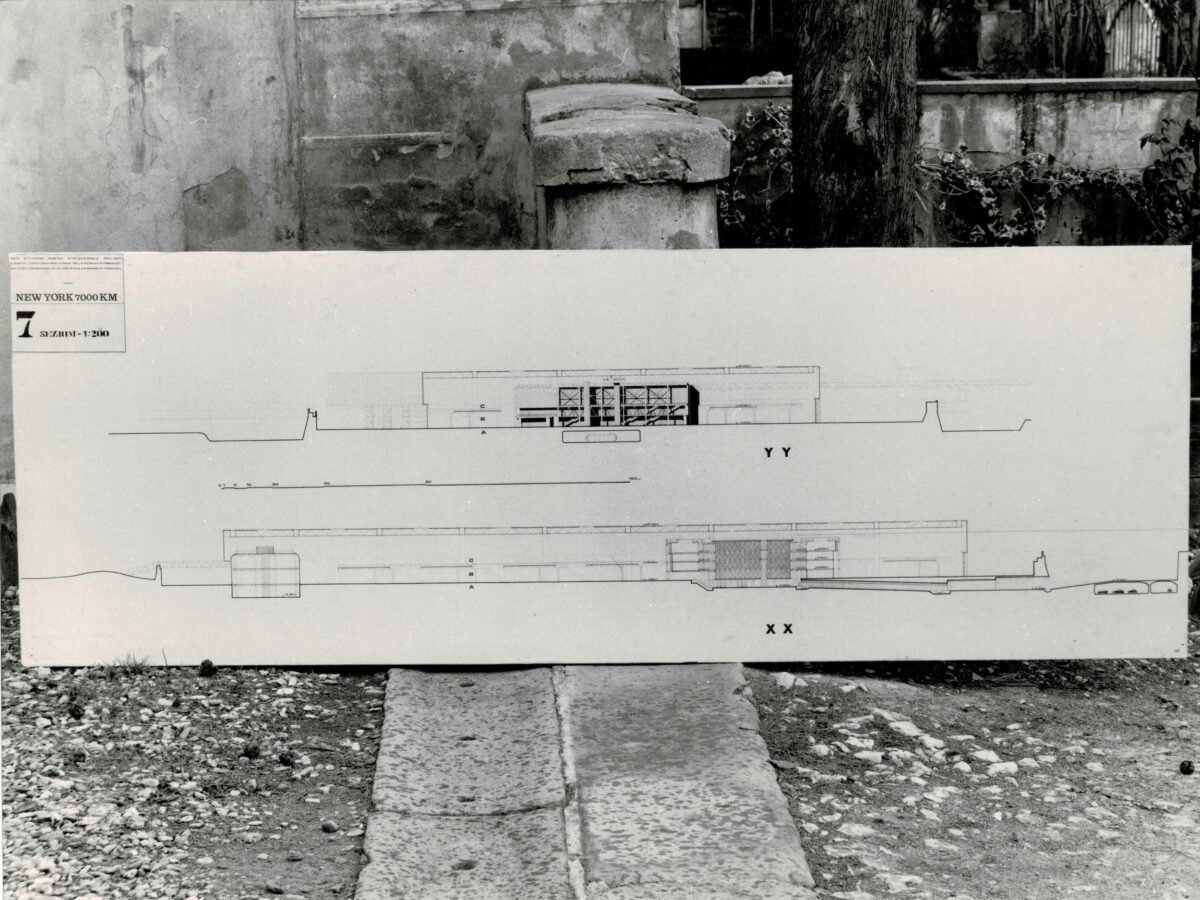

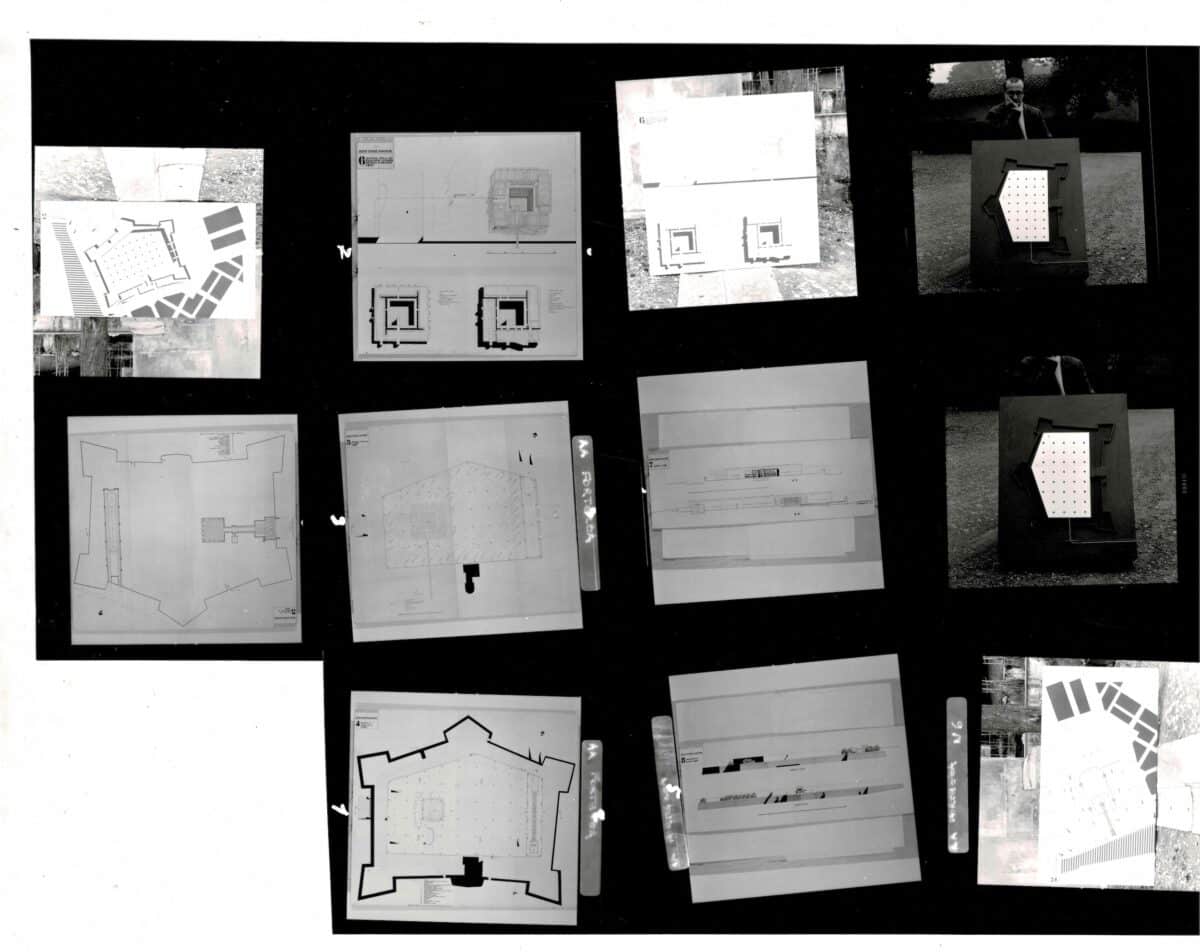

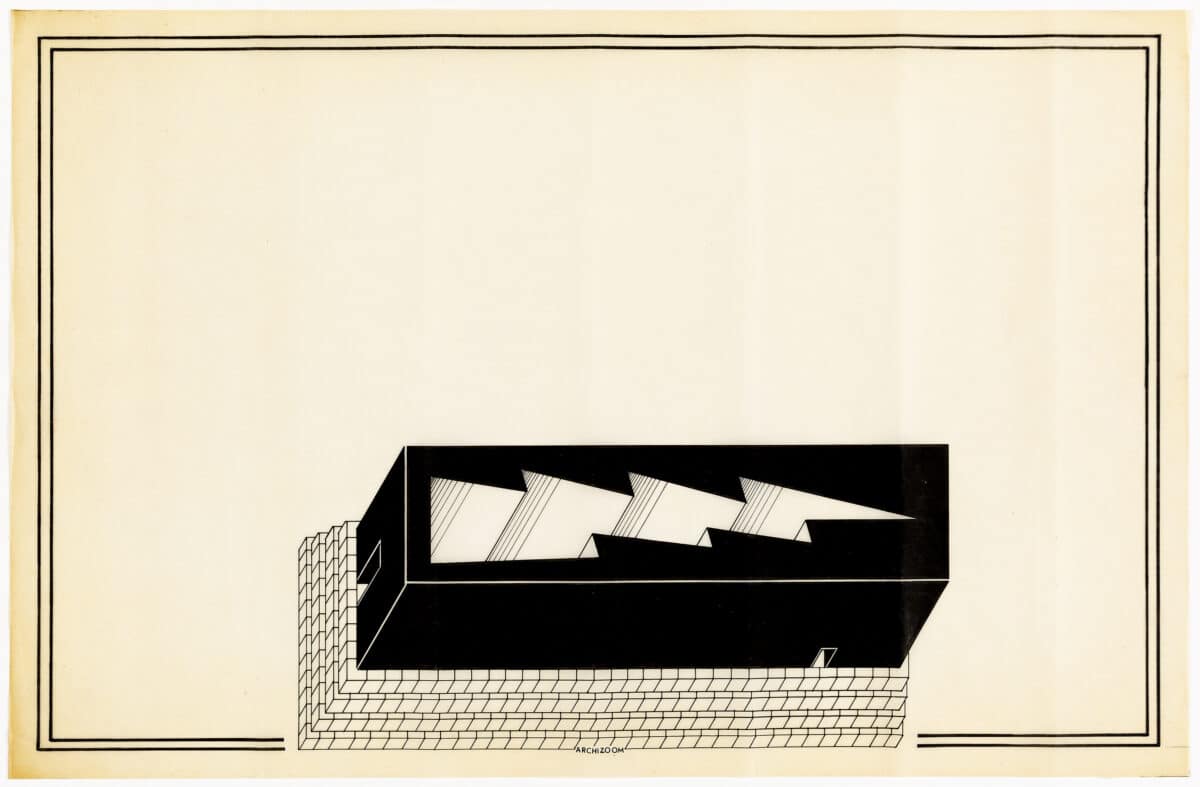

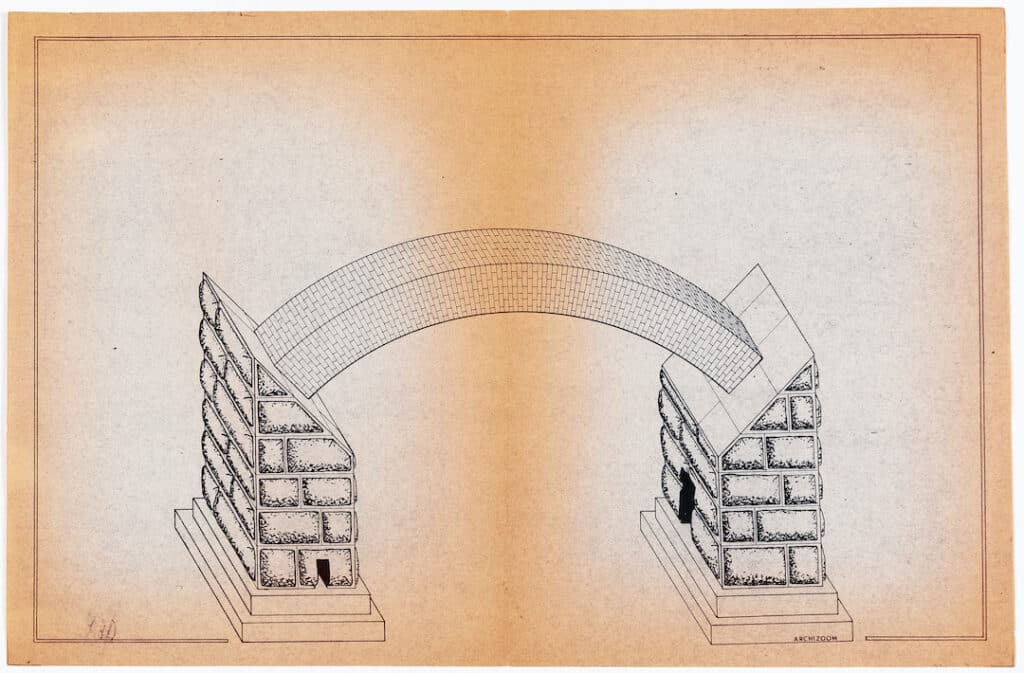

FORTEZZA DA BASSO, 1968

‘Fortezza da Basso’ was Archizoom’s 1968 entry to a national ideas competition for the relocation of the International Artisan Fair within Florence’s Renaissance fortress, the Fortezza da Basso, designed by Antonio da Sangallo the Younger. The competition called for entrants to cover and infill the internal space enclosed by the fort’s walls. Archizoom’s guiding principle was to avoid a formal confrontation with the historic building, opting instead for a neutral intervention. They proposed an abstract, factory-like structure defined by a singular, expansive roof: an anonymous built form in which the interior takes centre stage. The resulting environment is open and flexible, allowing the exhibition’s functions and programmes to be freely organised and partitioned according to need. The project marks a decisive shift from Archizoom’s earlier Pop-inspired production towards a new design agenda. By eliminating the formal qualities of the architectural object and focusing instead on the ‘elastic range of use’ of its interior, it signalled their first step towards ‘No-Stop City’ and the emergence of a ‘non-figurative architecture.’ Also, this reflected a deeper analytical turn in their work: the identification of modern architecture’s austere and indifferent forms as the defining visual outcomes of the capitalist city. The Drawing Matter Collection holds photographic documentation of Archizoom’s competition entry, including photocopied materials. Notably, Archizoom competed against fellow Radical group, Superstudio—whose entry is also held in the collection—but neither won the project; it was awarded to Pier Luigi Spadolini and was later constructed between 1974 and 1976.

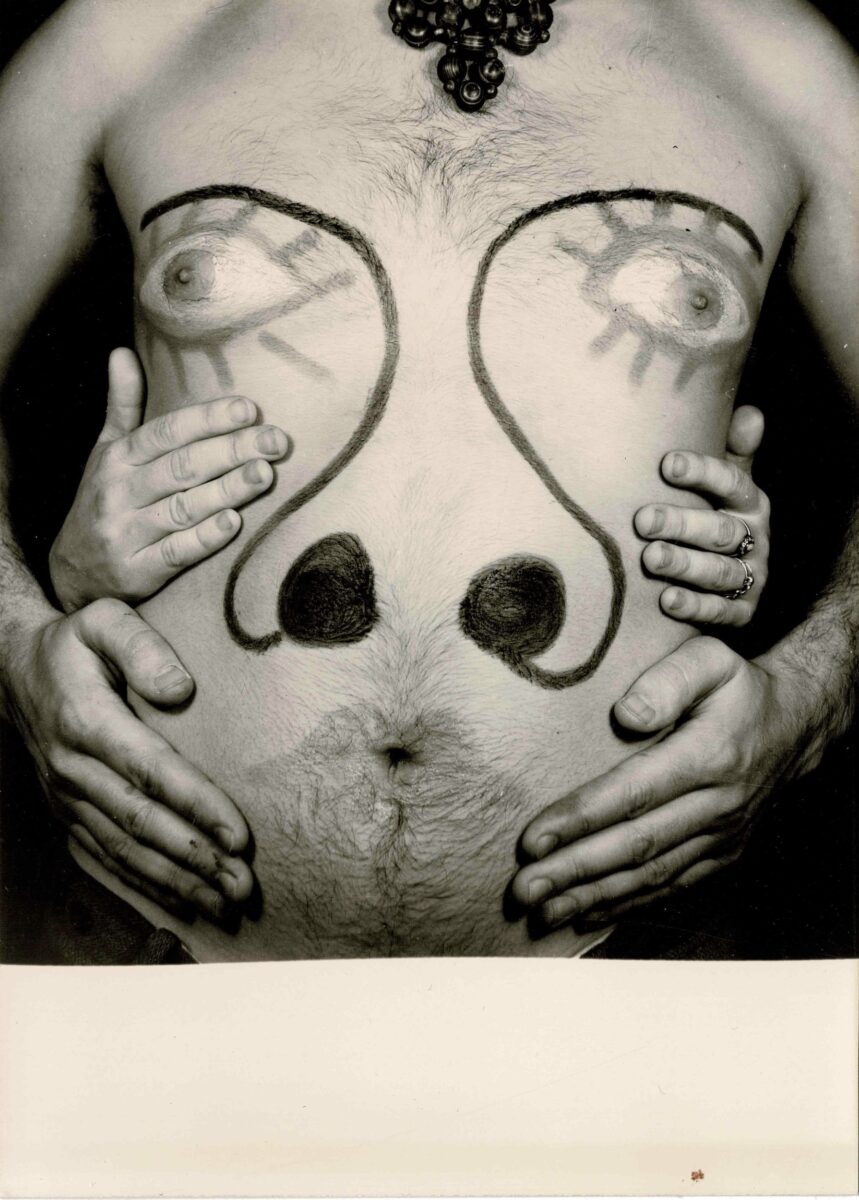

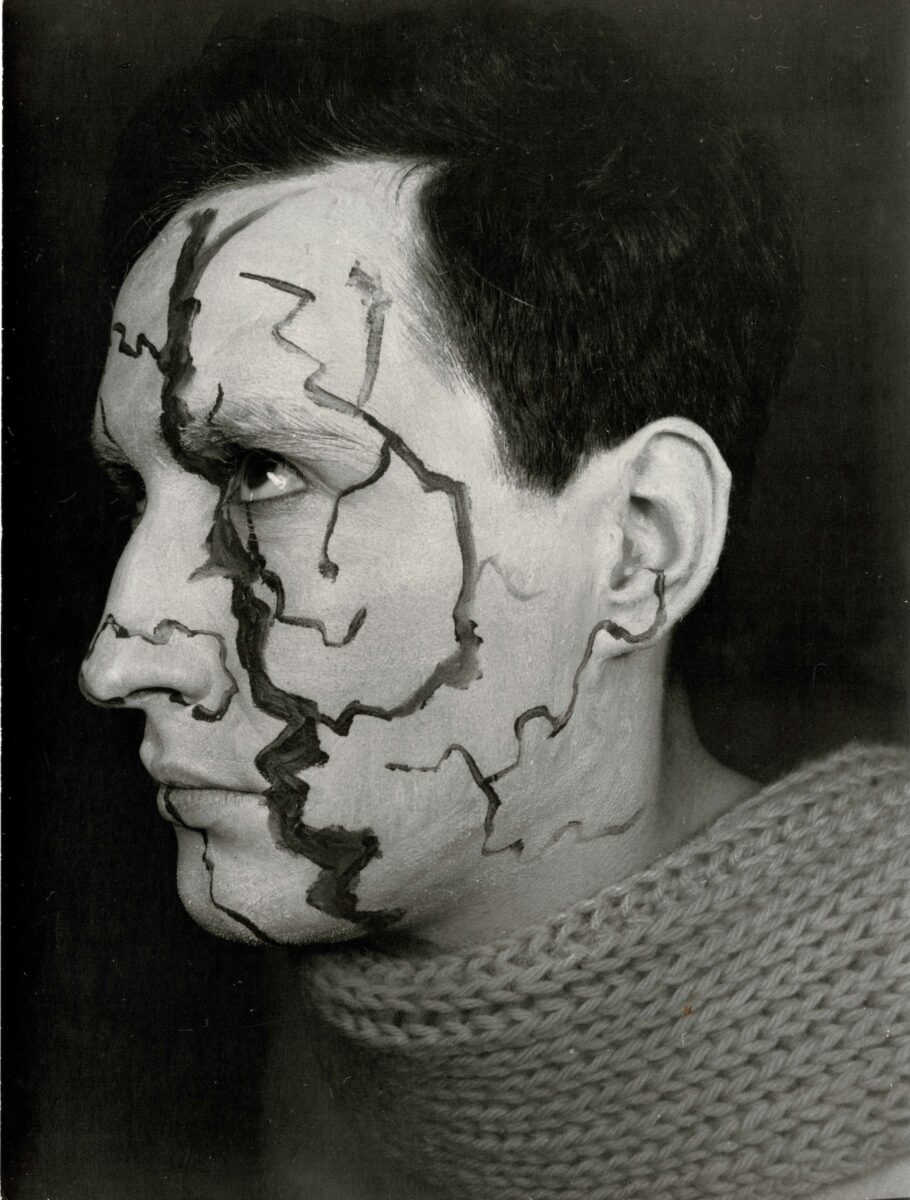

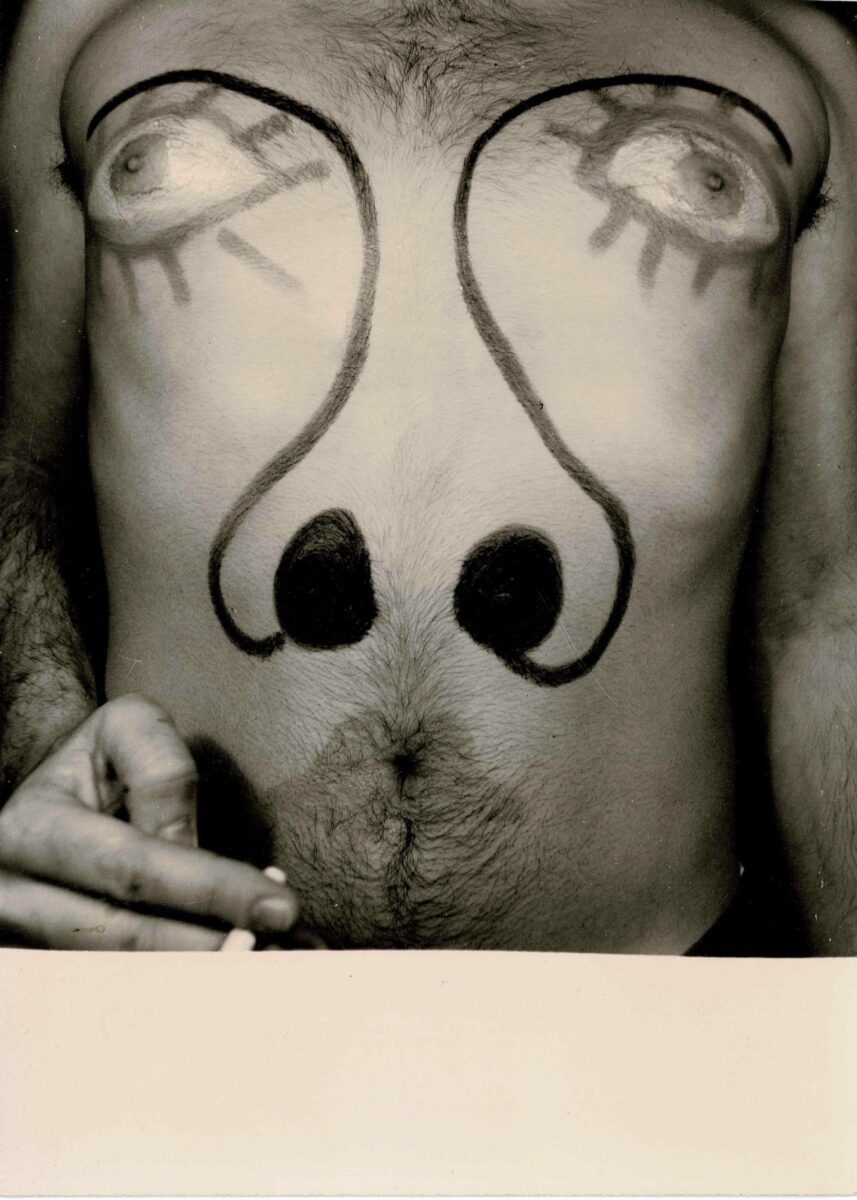

TRUCCHI, 1968

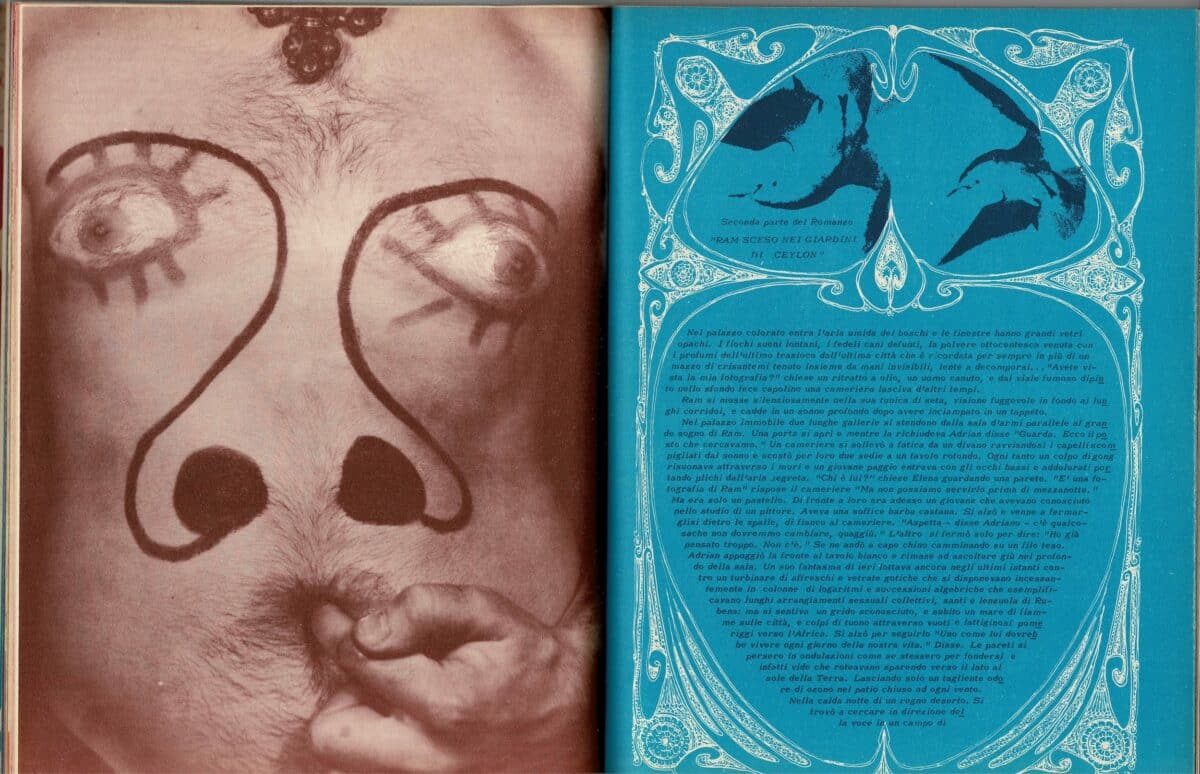

Drawing Matter holds a series of black and white photographs and contact sheets entitled ‘Trucchi’ (‘Tricks’ or ‘Make-up’). Andrea Branzi painted landscapes, textures, and brick walls on the faces of Nicoletta Morozzi and Massimo Morozzi as well as a face on the torso of Dario Bartolini. It was an exercise that explored the body’s potential communicative power: they took the face, our most illustrative feature, and experimented with its placement or removal from the body. This instrumentalisation of the body was informed by the Body Art movement of Arte Povera and the work of revolutionary psychoanalyst Wilhelm Reich. Four of these photos were included in Pianeta Fresco ⅔ edited by Fernanda Pivano and Ettore Sottsass Jr. and published in December 1968. They were also reproduced later in a 1972 edition of IN magazine, edited by Ugo La Pietra.

NO-STOP CITY, 1968-72

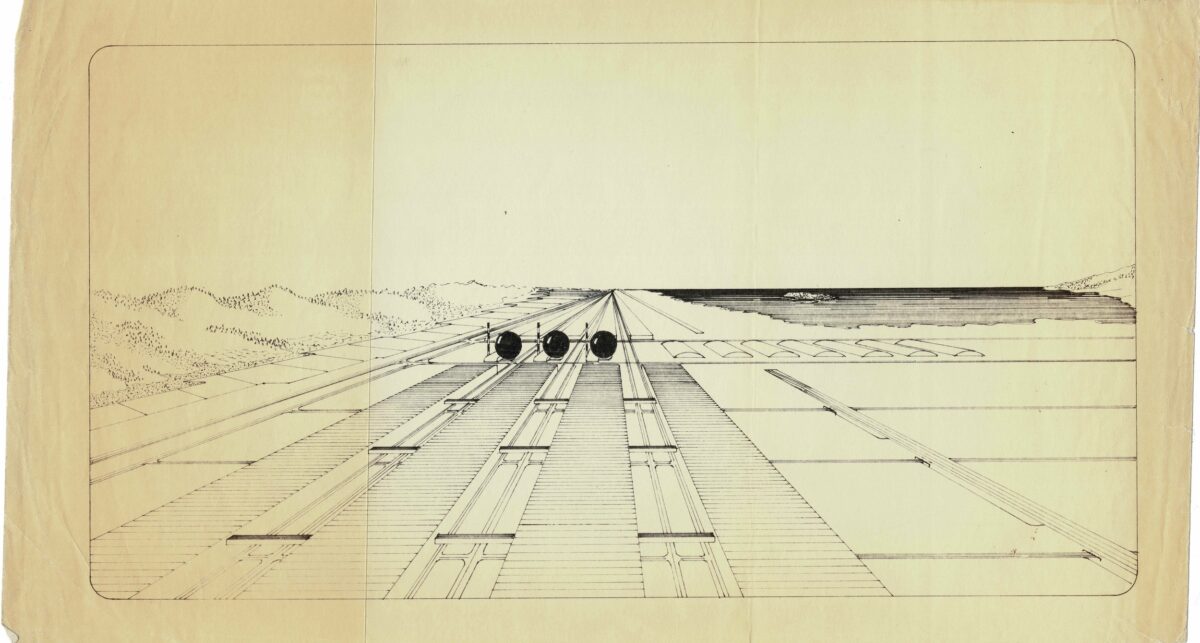

Developed between 1968 and 1972, No-Stop City stands as Archizoom’s most consequential project. It was a deliberate attempt to formulate a ‘non-figurative architecture,’ negating the formal and expressive qualities of the architectural object, to recast the city as the central critical category. In Archizoom’s words, it was a paradigm for ‘a city without architecture’: boundless, without centre, without exterior, homogeneous, qualitatively neutral, stripped to its bare infrastructures and conceived as a project for total urbanisation. The project is regarded as a theoretical recasting of the Miesian architectural reduction to its bare, industrial essence and the principles of Ludwig Hilberseimer’s Großstadt-Architektur (1927), read through Manfredo Tafuri’s critical assessments on architecture as capitalist development, which later culminated in his Architecture and Utopia (1973). Indeed, on the one hand, No-Stop City brings to completion what, for Archizoom, had always been the goal of modern architecture: namely, the dissolution of architecture itself; on the other hand, it presented its inner structure: a continuous metropolis conceived as a direct, rational expression of its economic function within late capitalism—a metropolis that corresponds to the logic of the market.

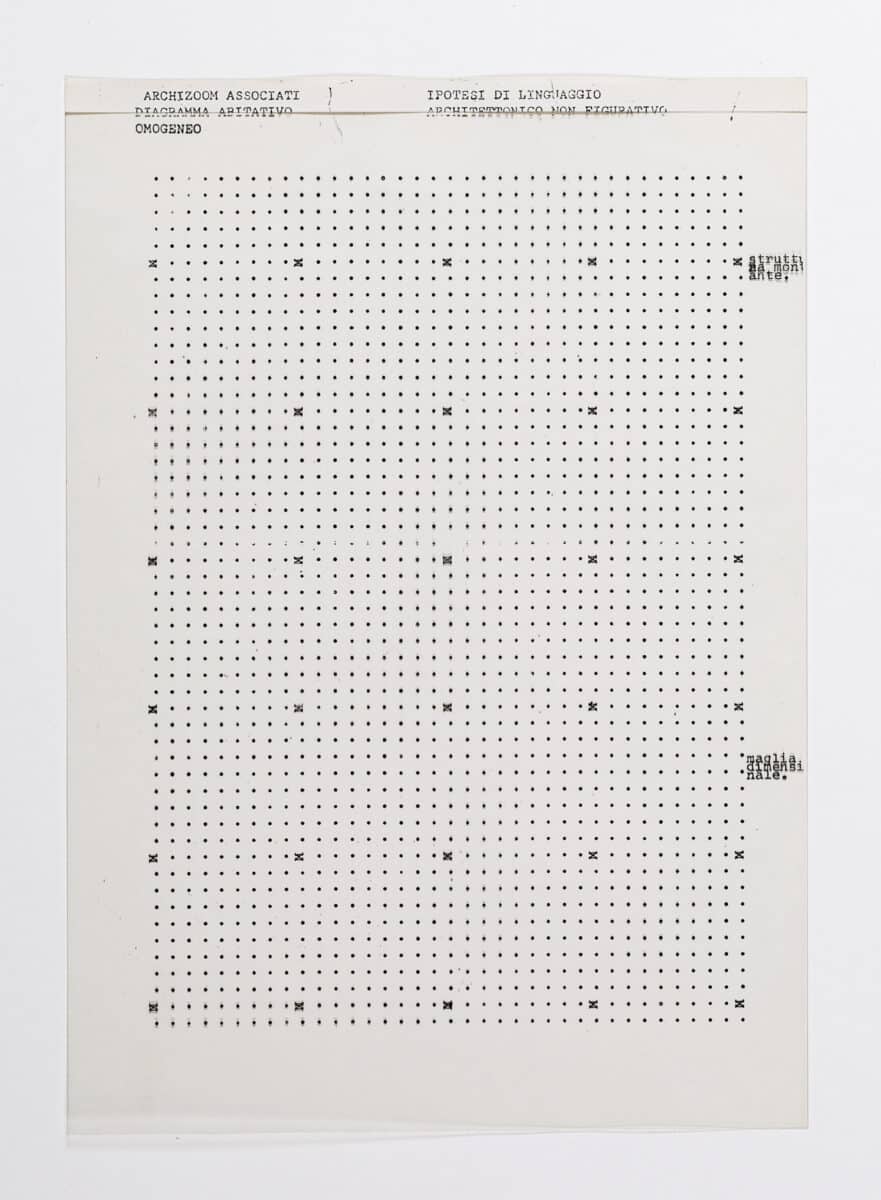

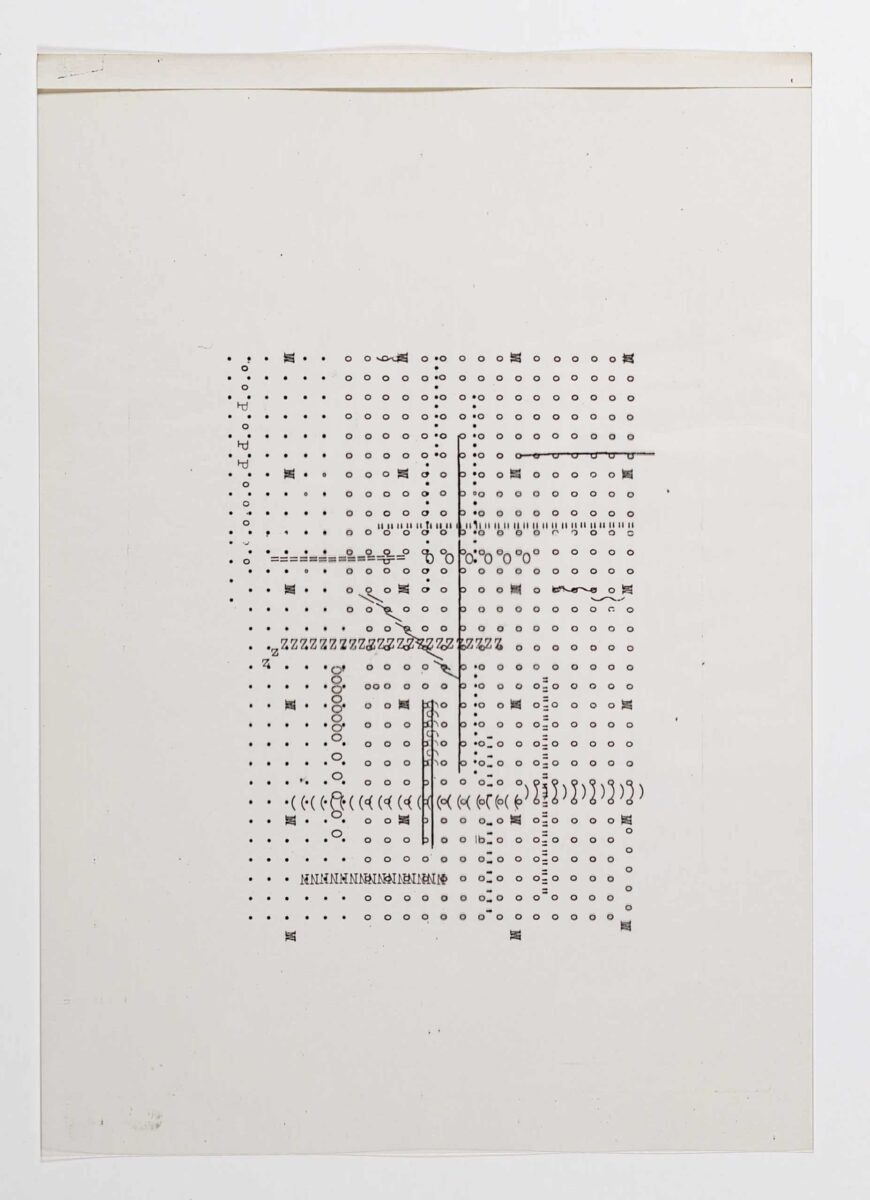

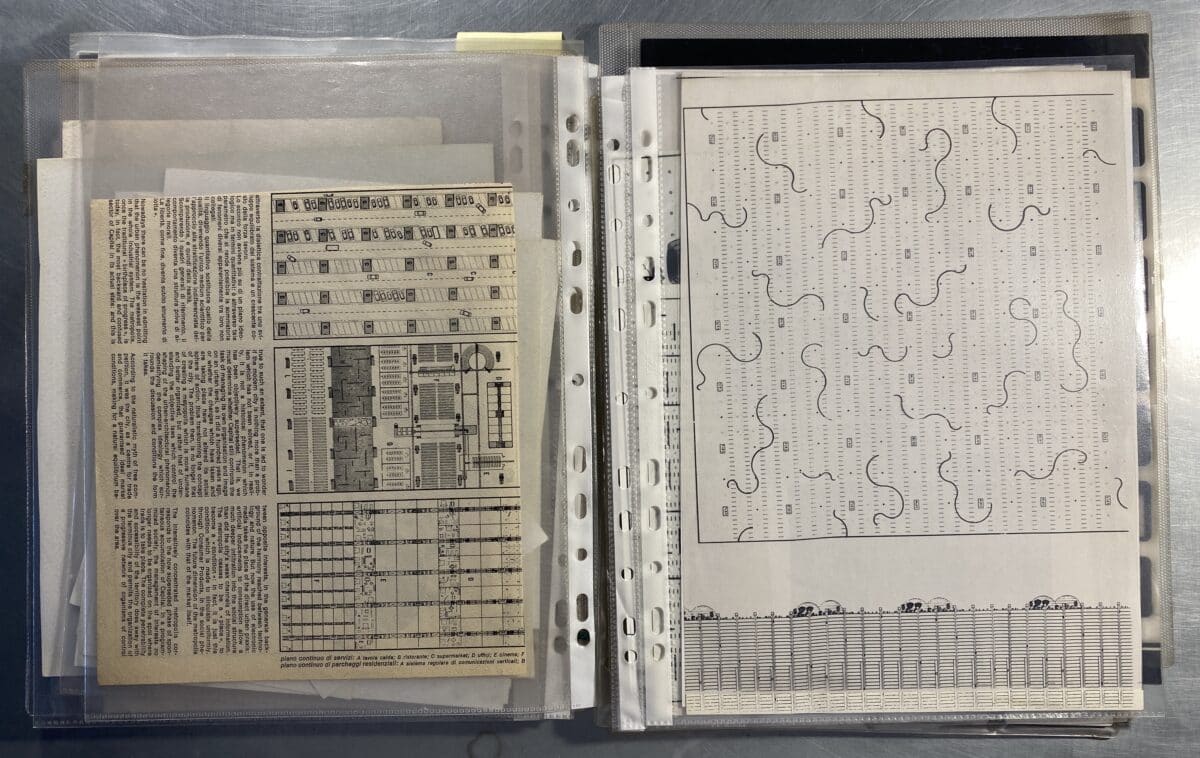

The first iteration of the project is the ‘Diagramma Abitativo Omogeneo: Ipotesi di Linguaggio Architettonico Non Figurativo’ (‘Homogeneous Housing Diagram: Hypothesis for a Non-Figurative Architectural Language’) from 1968. Executed on a typewriter, it consists of a series of abstract diagrams based on the depiction of a grid ‘typed’ with dots and X’s (DMC 2738.9.1). As Archizoom noted on the right side of the drawing, these glyphs represent at once a ‘structural frame’ (‘struttura montante’) and a ‘dimensional grid’ (‘maglia dimensionale’). This ensemble represents the minimum infrastructural elements to erect a built environment, one that, once laid out, allows an expansive degree of interior reconfiguration and movement (DMC 2738.9.2). These drawings, as the subtitle suggests, made explicit Archizoom’s quest for a non-figurative architecture; one that eliminates the linguistic and subjective dimension of architecture, while farcically exaggerating the principles of minimum dwelling so dear to the modern movement.

No-Stop City was first published in Casabella in June 1970 with the title ‘Città, catena di montaggio del sociale’ (‘City, Assembly Line of the Social’). The operational element of the factory’s assembly line functioned as the entry point for two foundational, critical aspects of No-Stop City. First, it postulated labour as no longer confined to the factory, rendering the whole society as a site of production and consumption. Second, it explicated how the factory is no longer the sole paradigm for an industrially produced architecture, proposing instead that the entire city can be conceived and produced through industrial logic. By expanding the scope of the assembly line, Archizoom sought to elucidate how the technical rationalisation inherent in a monetary economy permeates the social sphere, with the city acting as its primary incubator.

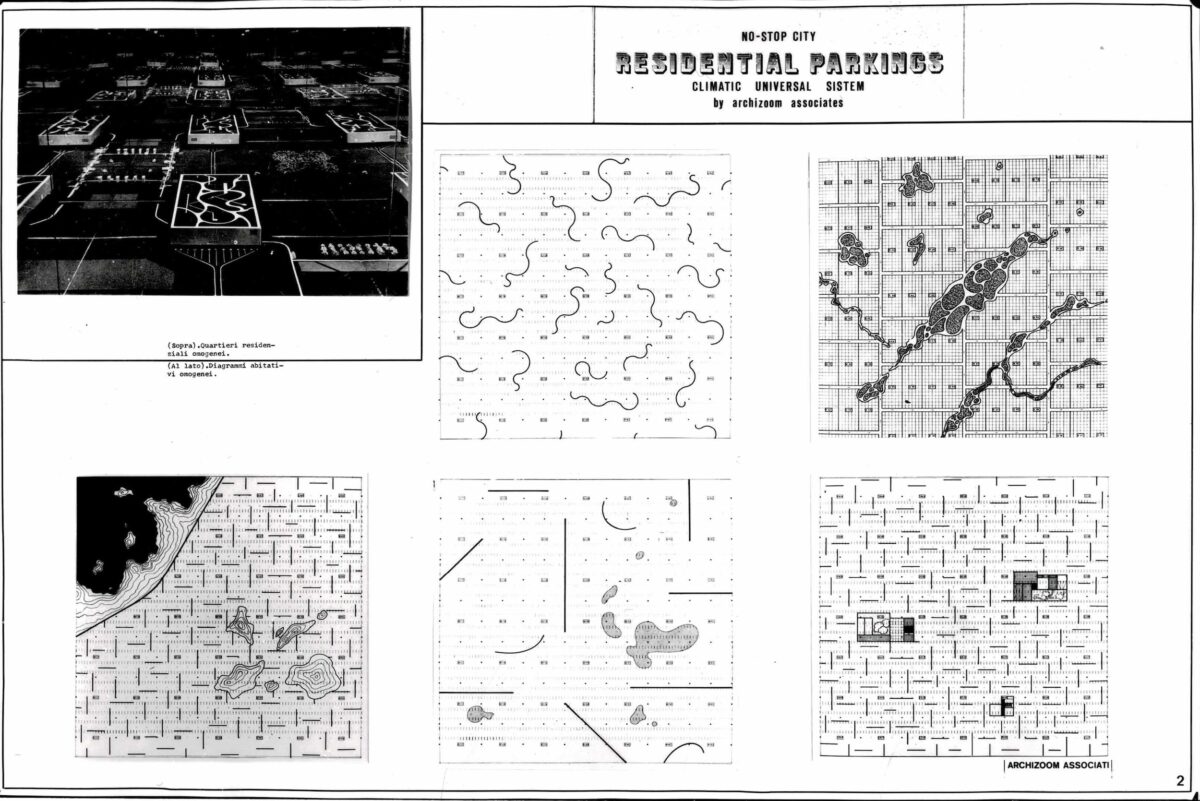

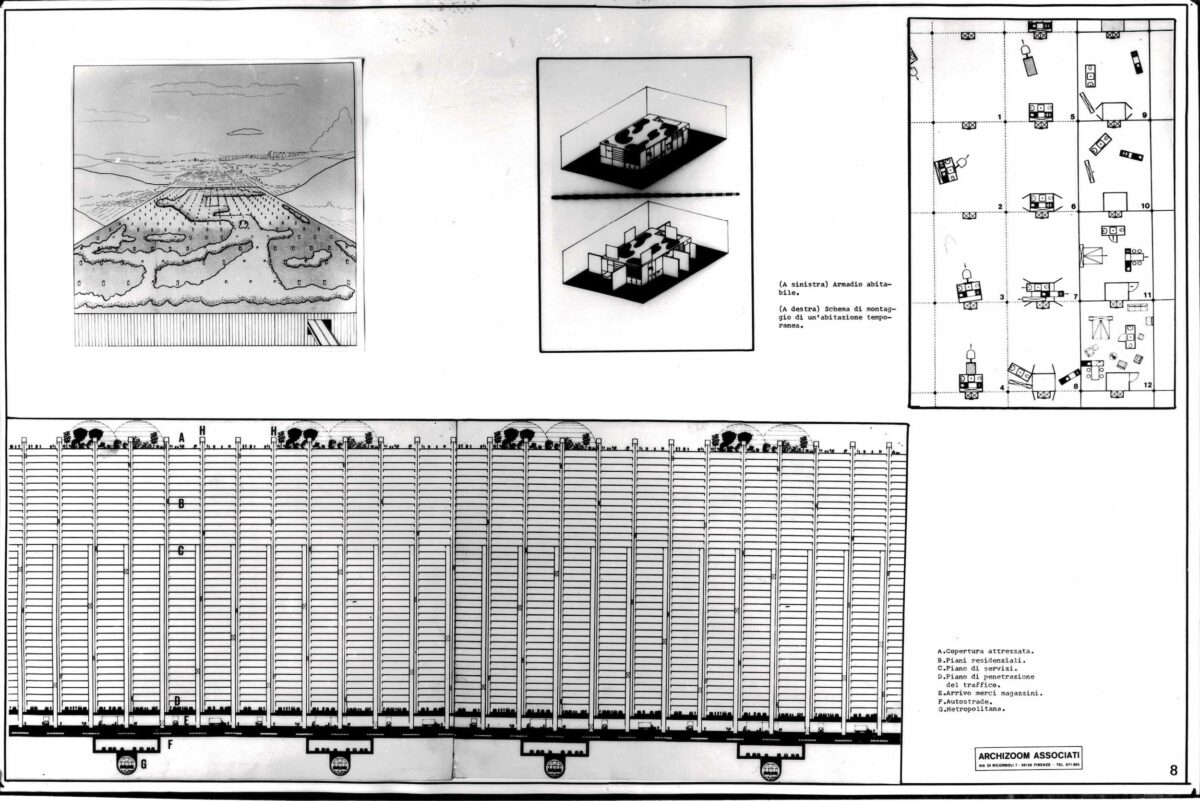

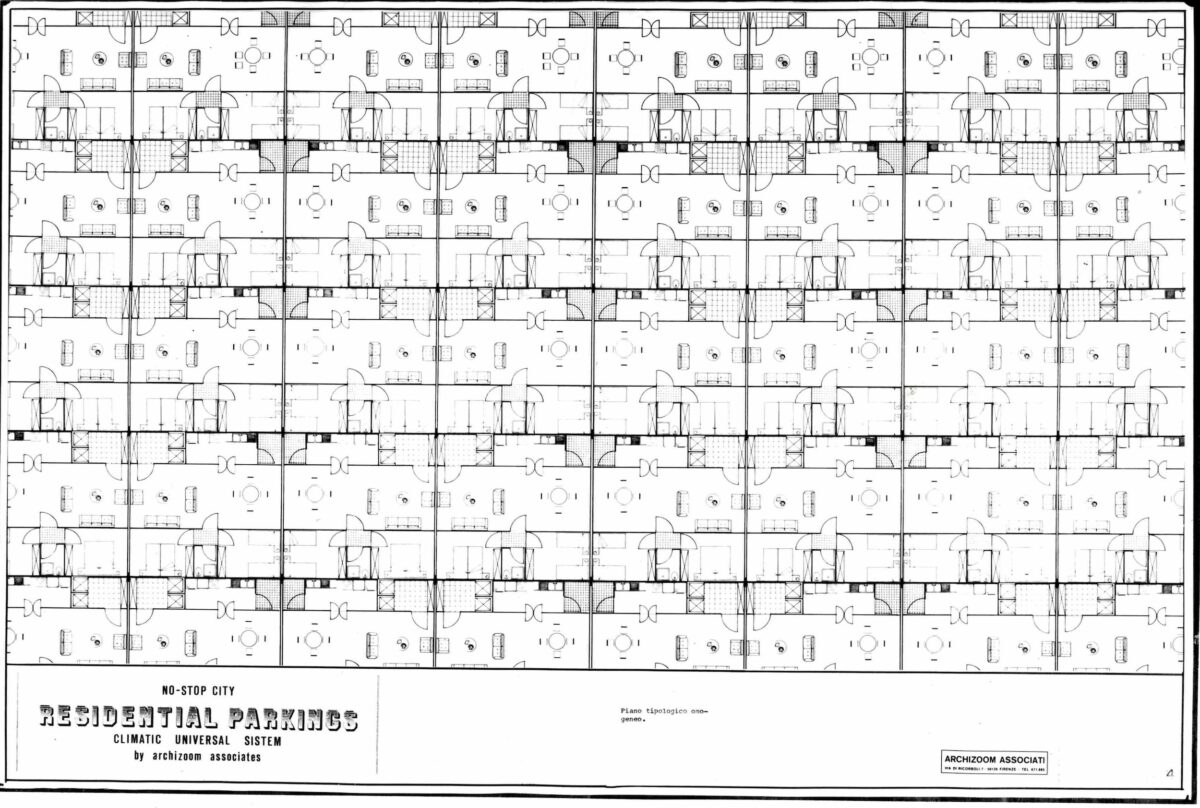

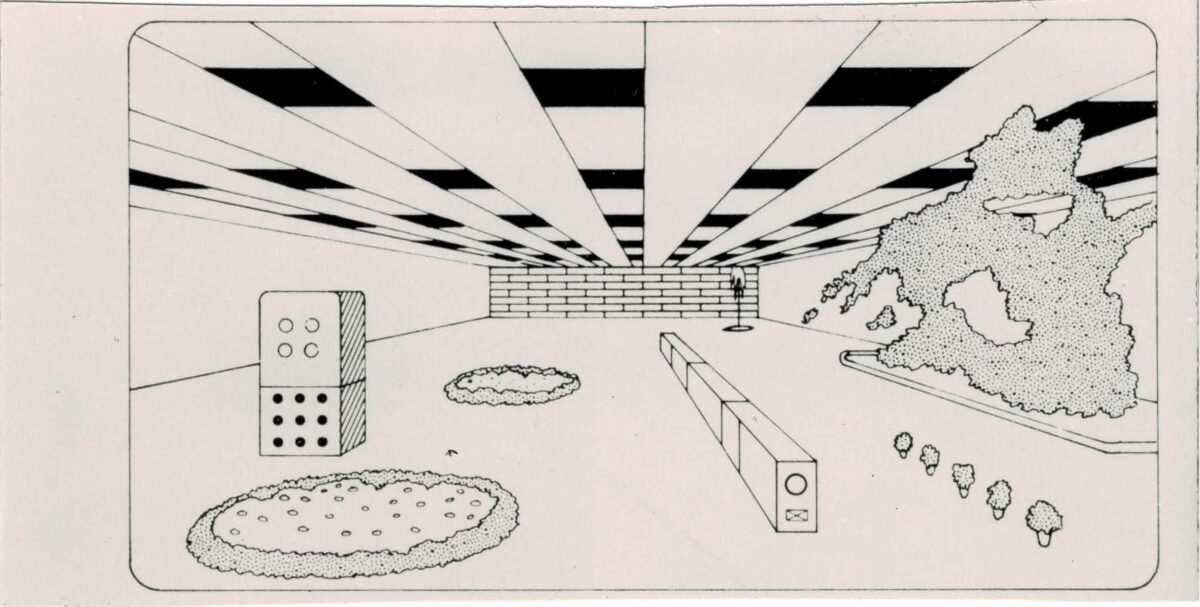

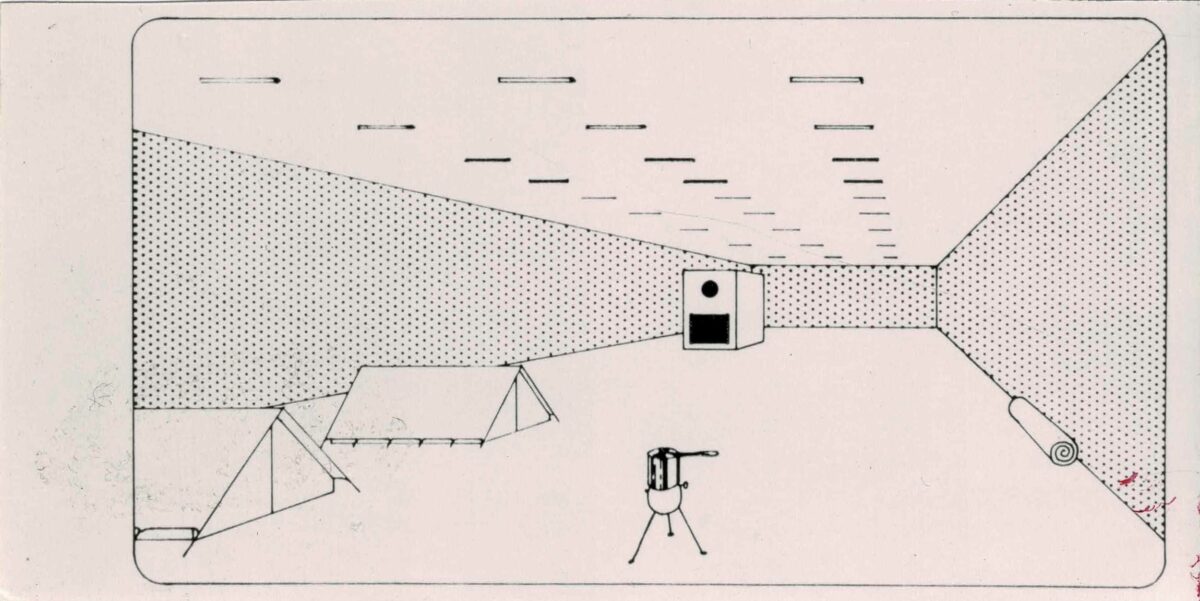

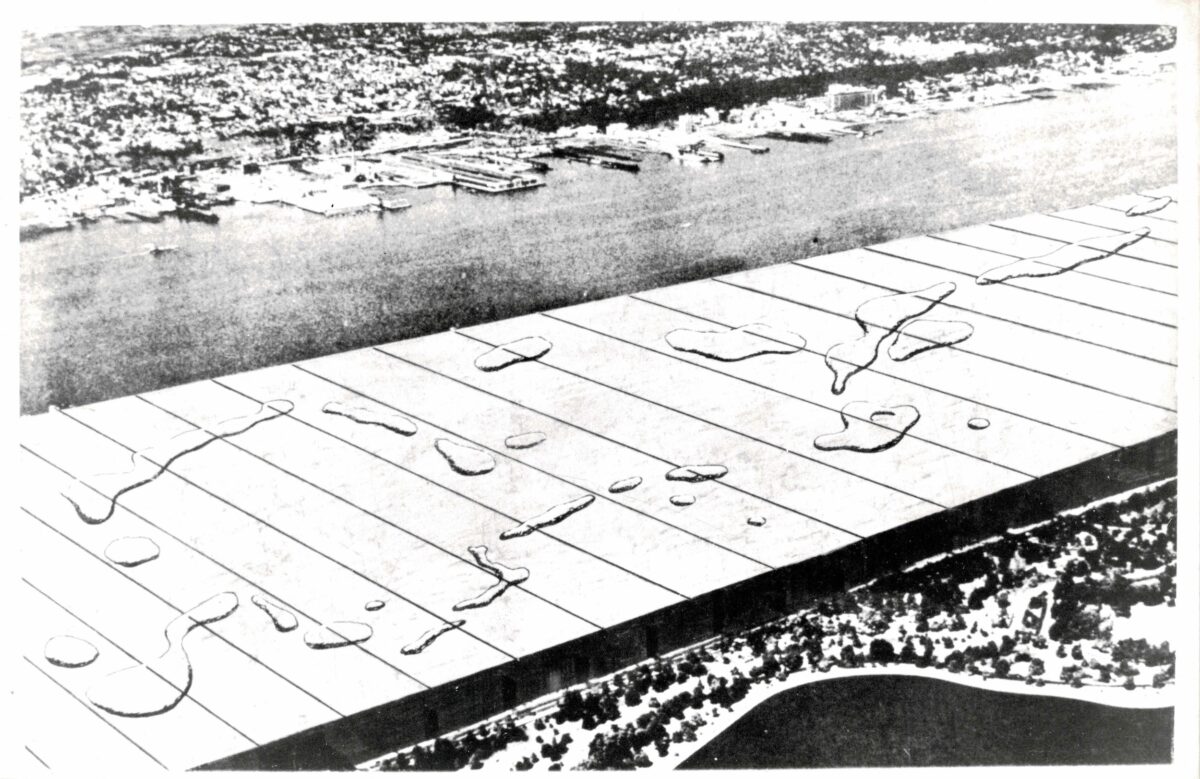

Drawing Matter holds a set of black and white images assembled on printed sheets with the title ‘Residential Parkings: Climatic Universal System,’ which primarily corresponds to material published in Domus n.496 (1971). In these representations, No-Stop City is turned inside-out, explicating the relationship between cell and city. Through the model of the supermarket, a universal system of air-conditioning and artificial lighting is extended into an open, infinite plan for habitation, transforming the city into parking lot facilities that provide multiple interior configurations. The prints on mylar (DMC 2738.9.11-12) depict perspective views of No-Stop City’s interiors, published in IN n.⅔ (1971), within Archizoom’s article ‘La distruzione degli oggetti’ (‘The destruction of objects’). These images aimed to depict what Archizoom termed ‘spazio-vuoto-attrezzato’ (‘equipped-empty-space’)—a proposal to suppress domestic figuration, opening up multiple, transient and dynamic forms of life.

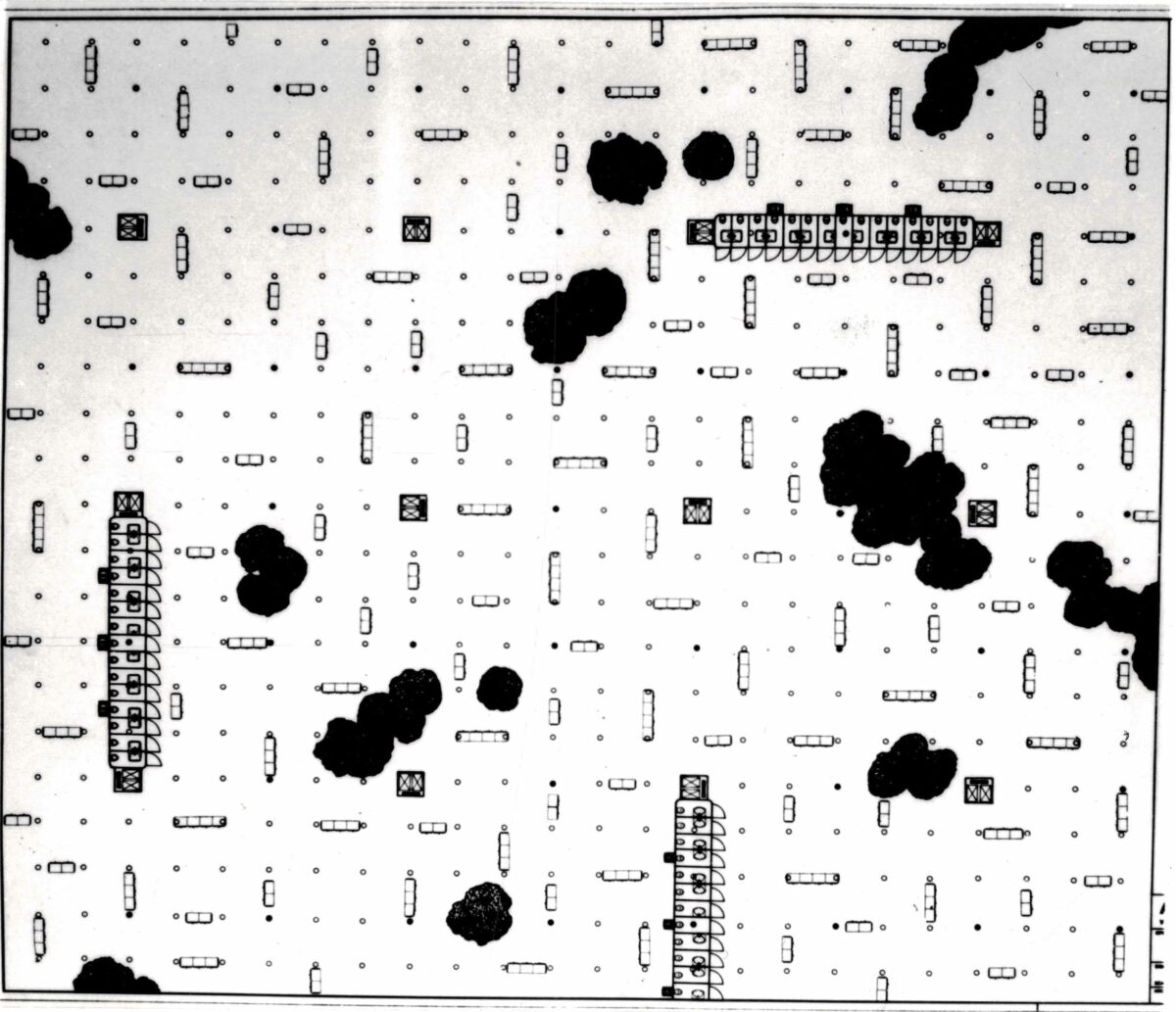

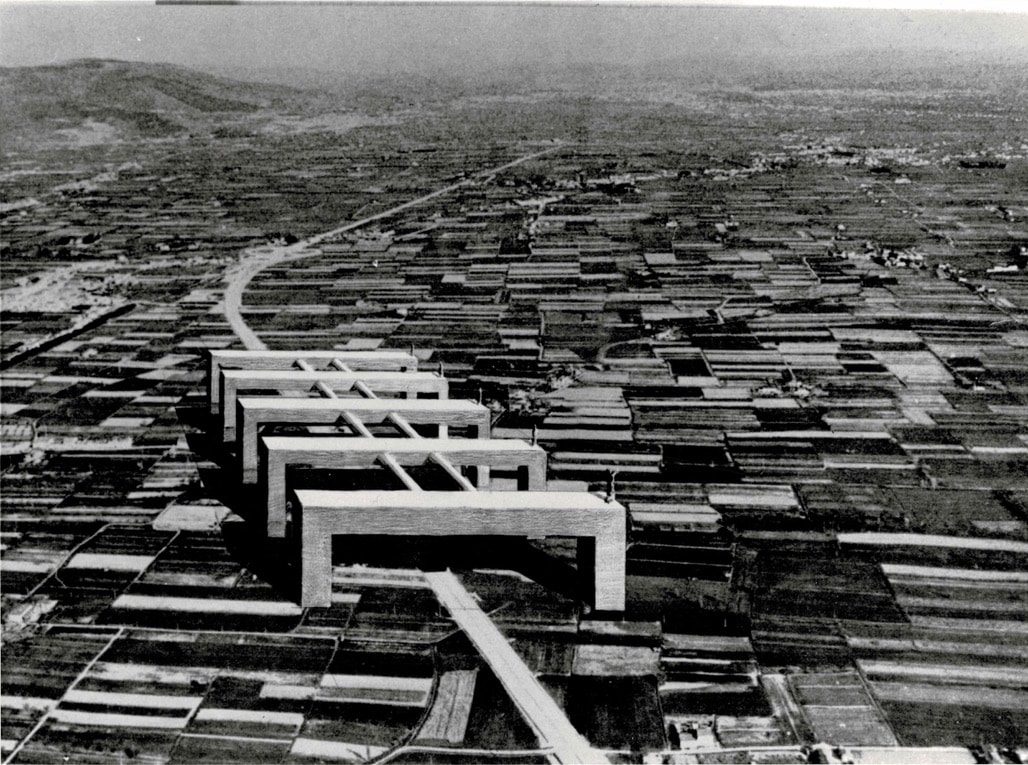

In the collection is also a print of ‘Paesaggio Urbano’ (‘Urban Landscape’), which illustrated the article ‘Distruzione e riappropriazione della citta’ (‘Destruction and reappropriation of the city’) published in IN n.5 (1972). The image depicts the last stages of No-Stop City. From the destruction of the architectural objects, here the investigation shifts towards the destruction of the city, understood as a series of formal, repressive episodes. This aerial, perspective view thus confronts it, vividly representing the dissolution of differences between city, landscape, and architecture into an homogenous surface.

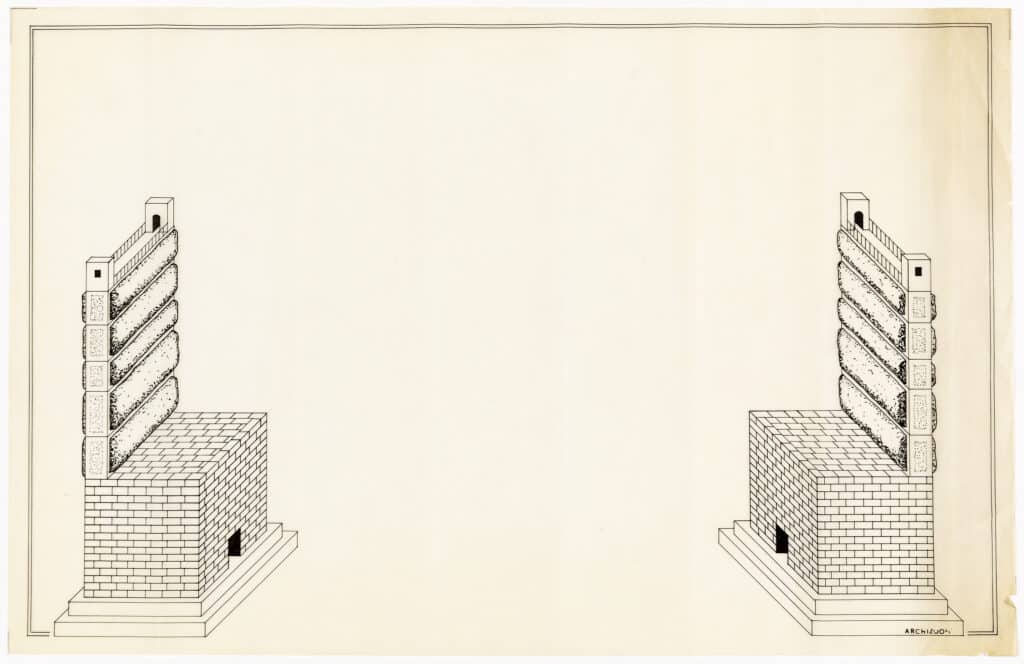

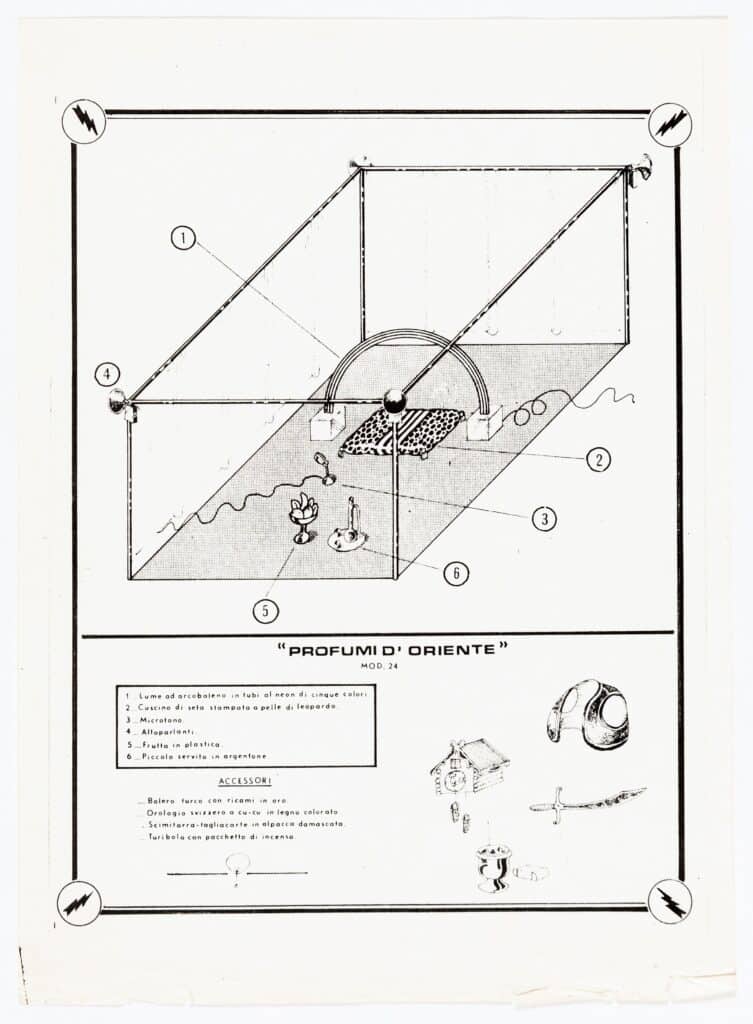

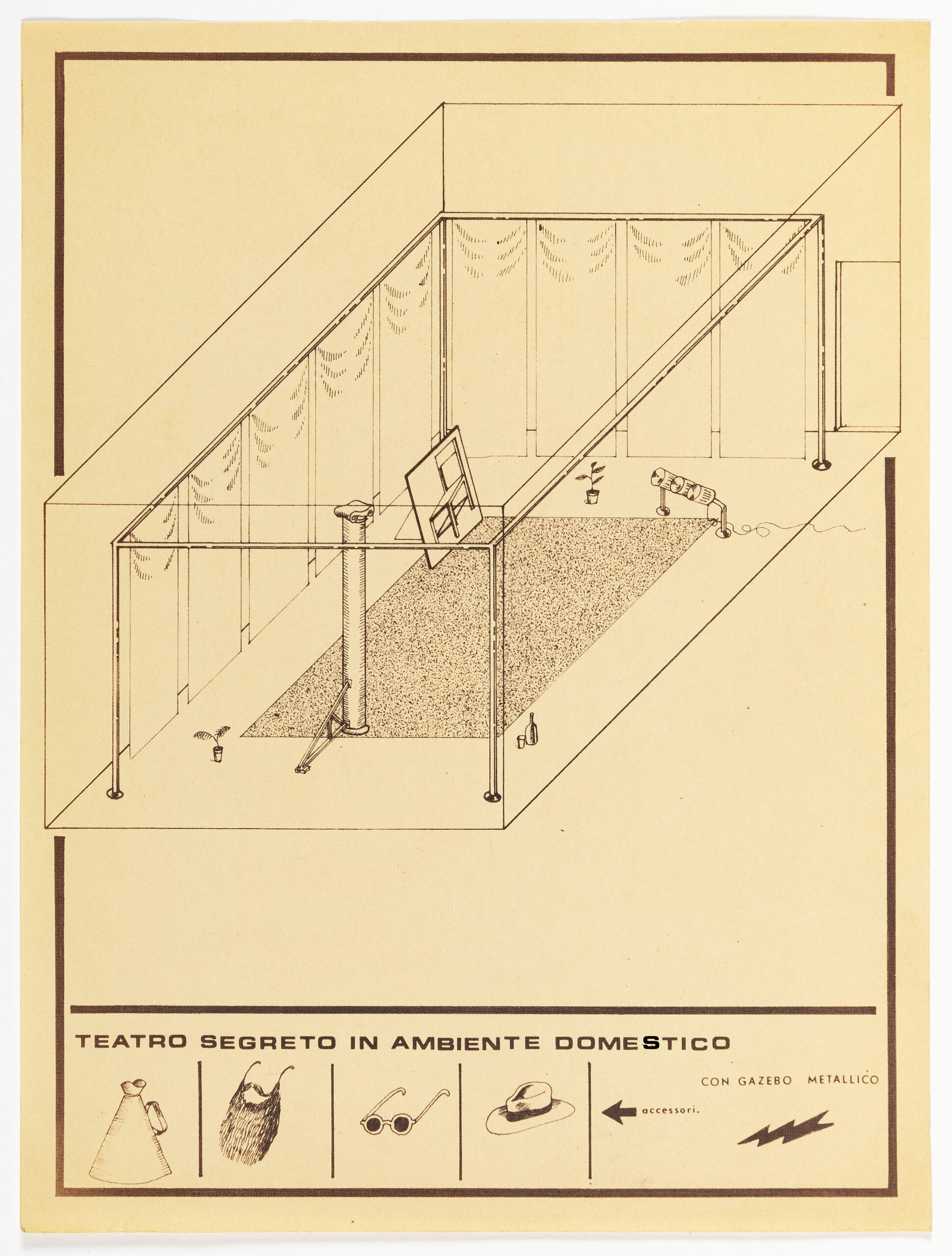

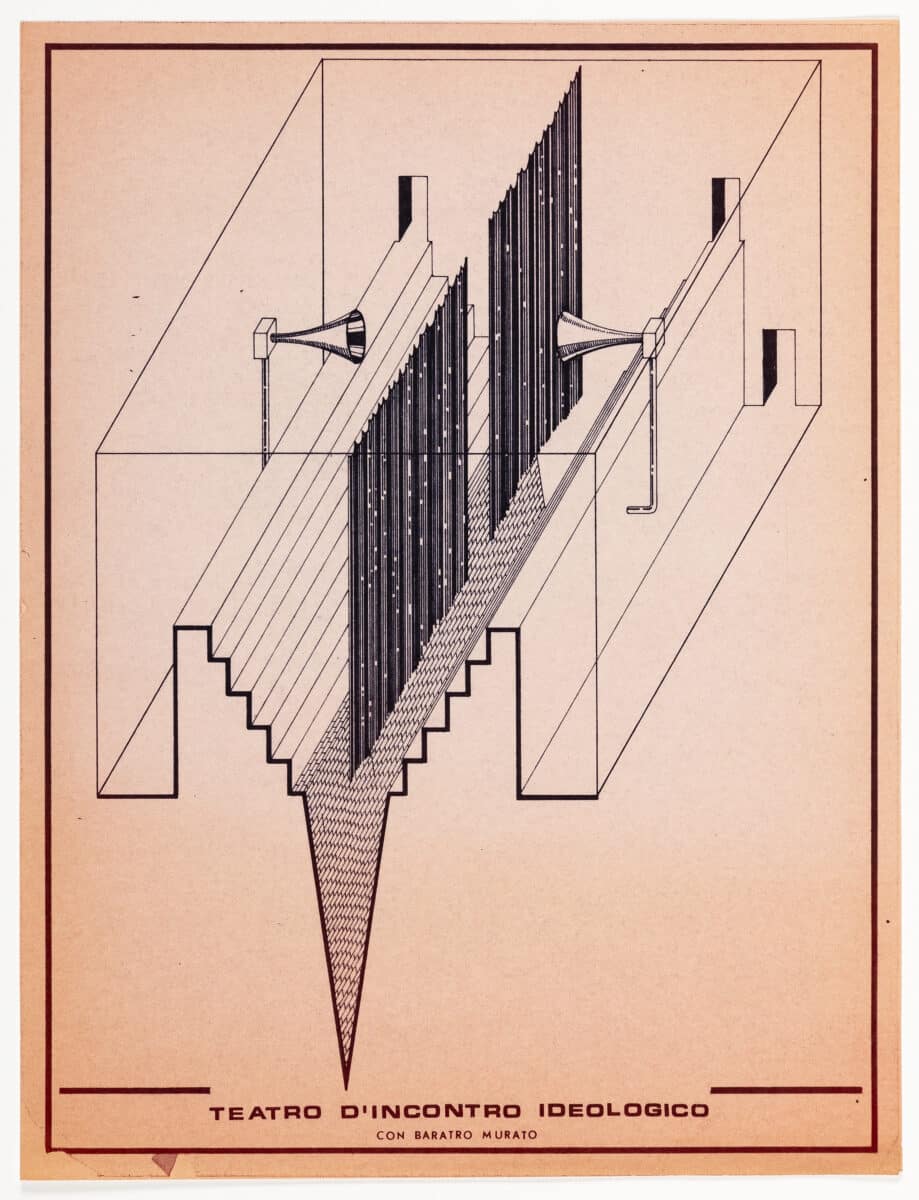

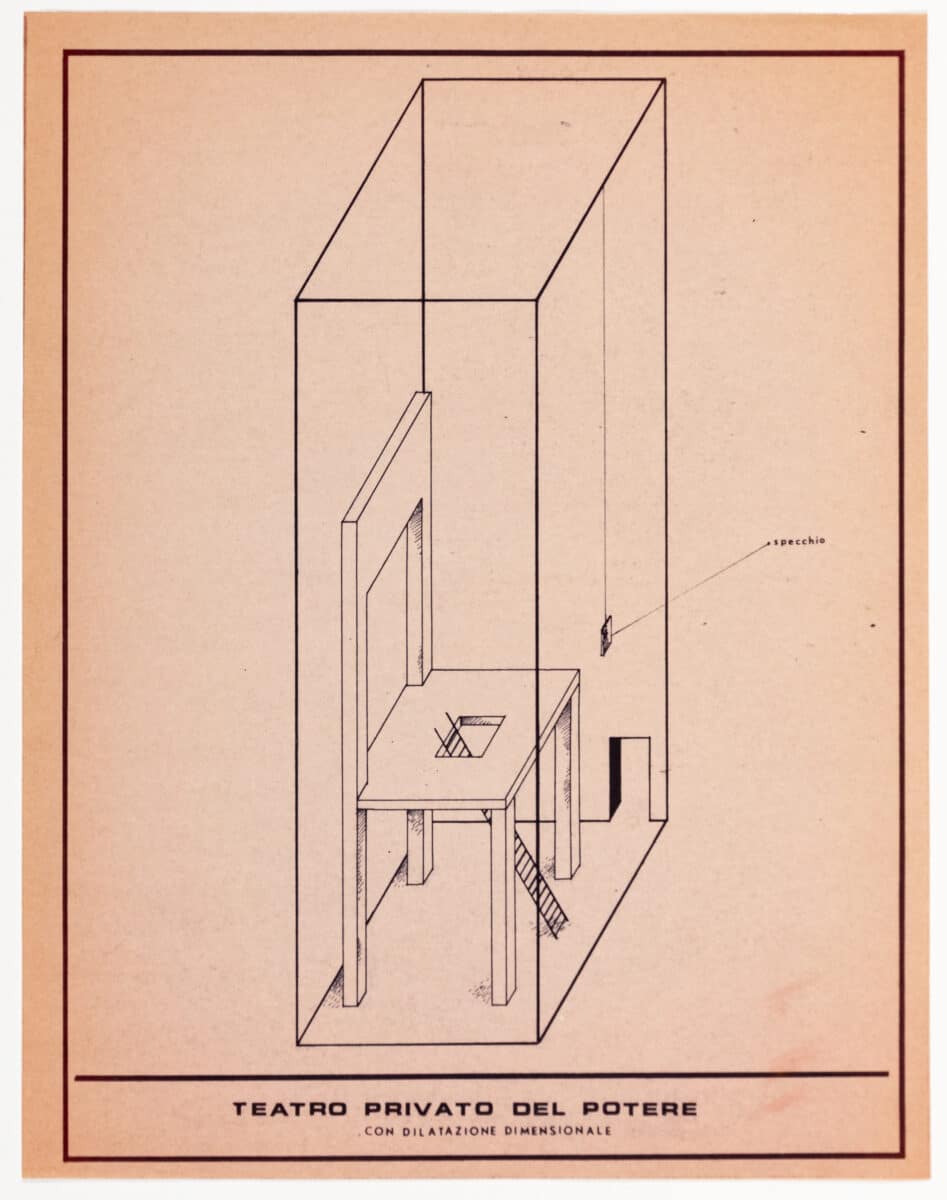

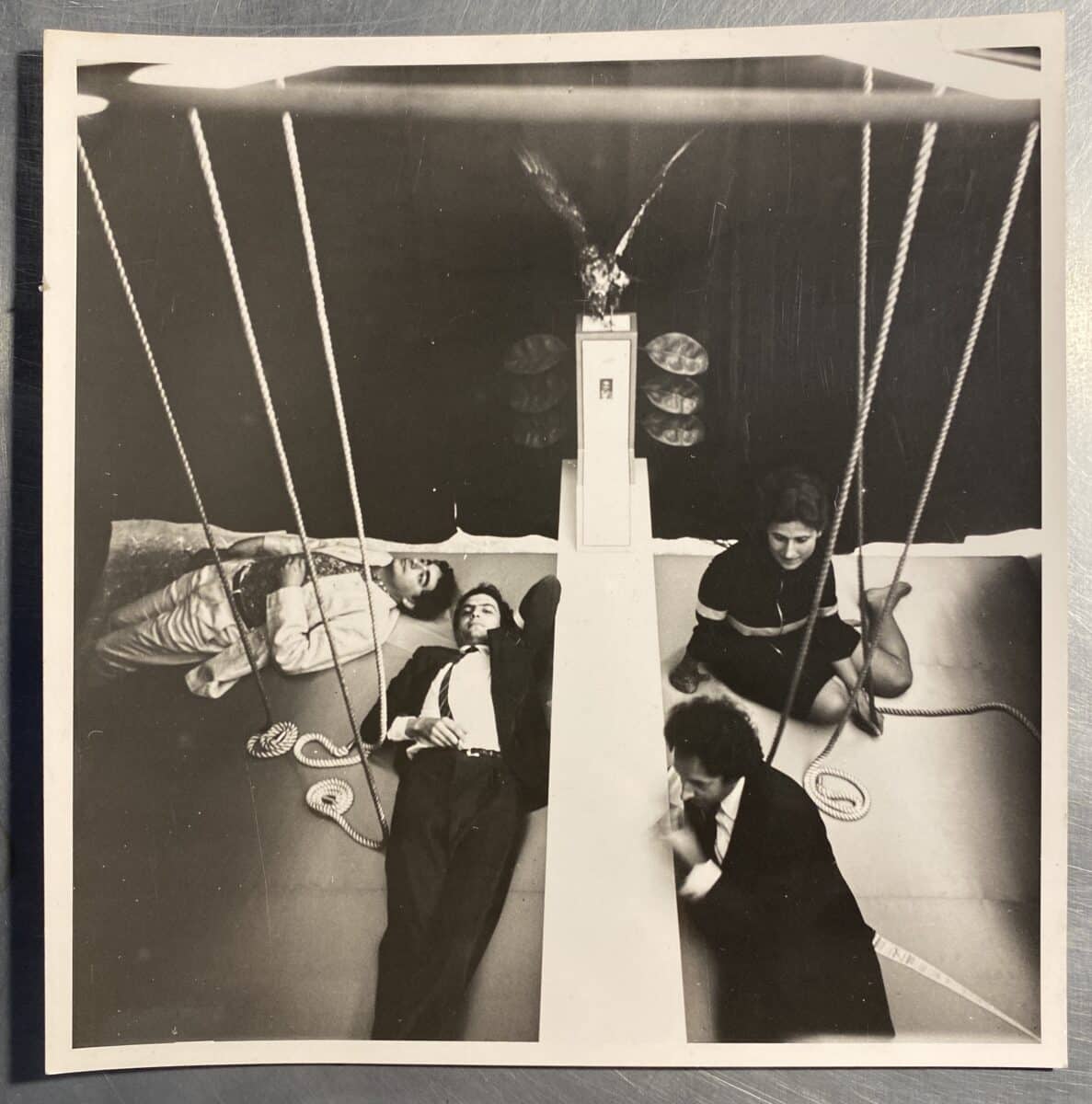

GAZEBOS, 1967 & TEATRI, 1968

Archizoom’s series of ‘Gazebos’ and ‘Theatres’ consist of images of microenvironments, published, respectively, in 1967 and 1968, in the magazine Pianeta Fresco. Despite being published in separate issues, both relate to Archizoom’s reflections on the question of dwelling where the modern ideals of monumental architecture give way to ephemeral tent-like environments. These are populated by staged, symbolic elements that, in their juxtaposition, defy cultural connotations. Such temporary set-ups depict artefacts charged with kitsch sensibility, including Islamic and Afro-tyrolese elements paired together, conceived to challenge the ideals of the bourgeois interior. The gazebo is a recurrent motif in Archizoom’s oeuvre and, although the ones present in the Drawing Matter collection were conceived for publication, the ‘Center for Eclectic Meditation’ in Agliana, Pistoia, in 1967, and the ‘Center for Eclectic Conspiracy’ for the 14th Triennale di Milano in 1969, became built examples.

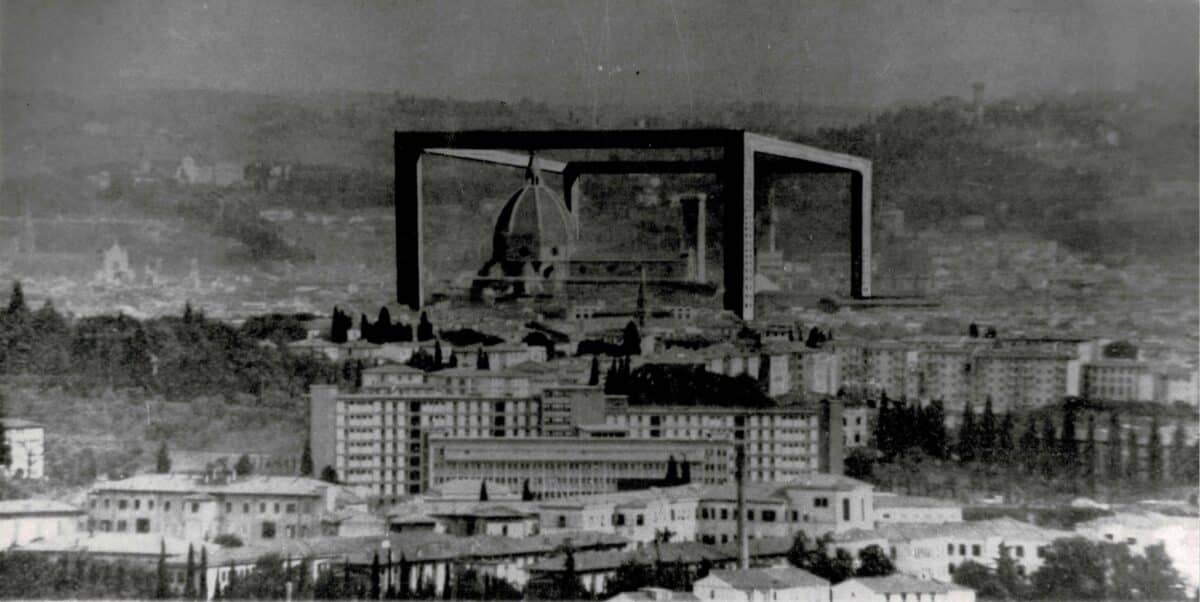

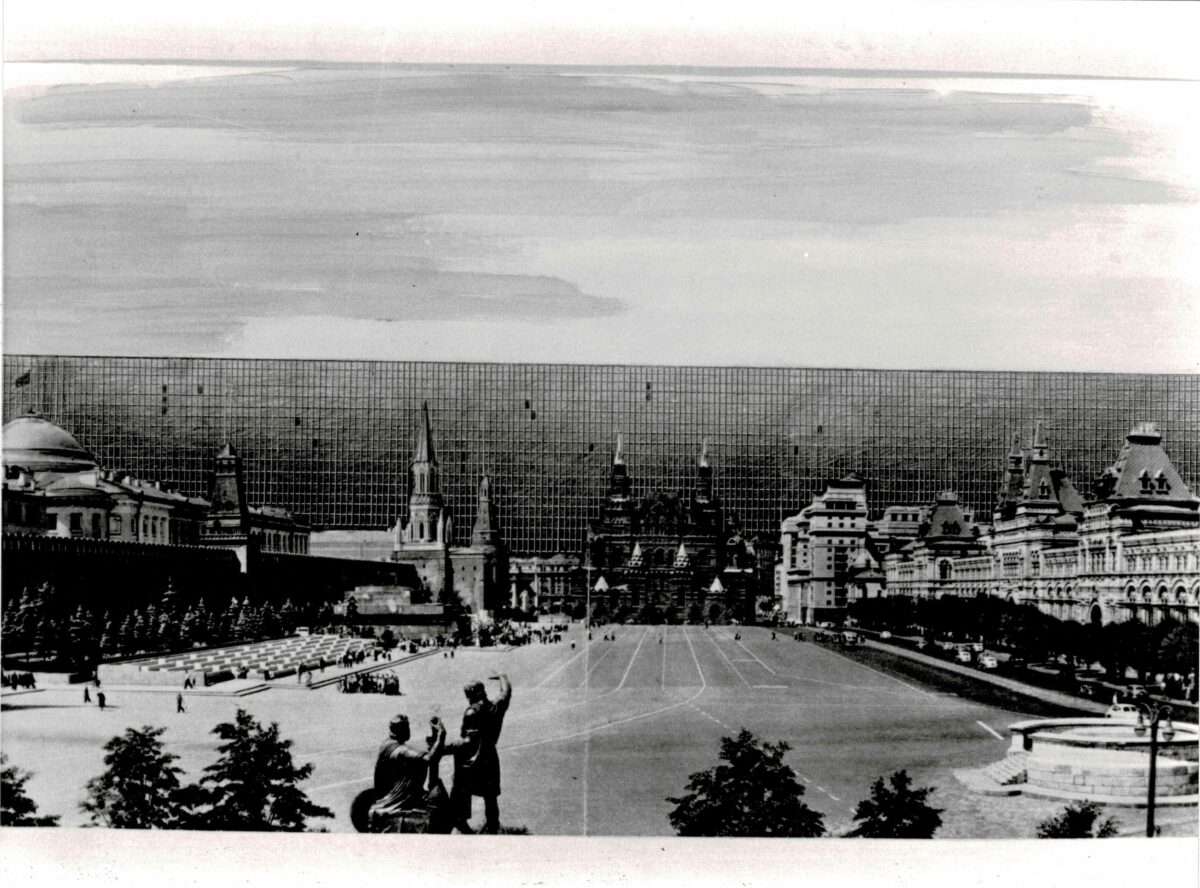

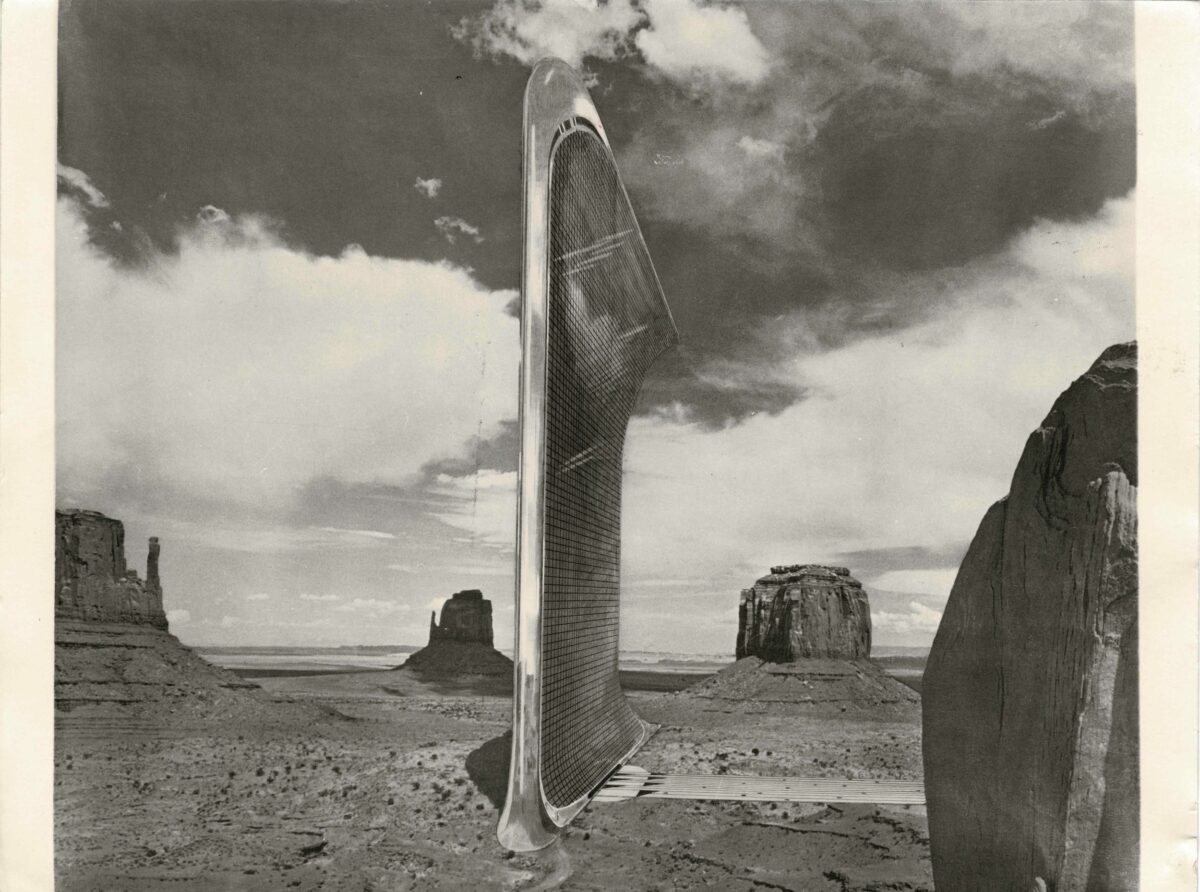

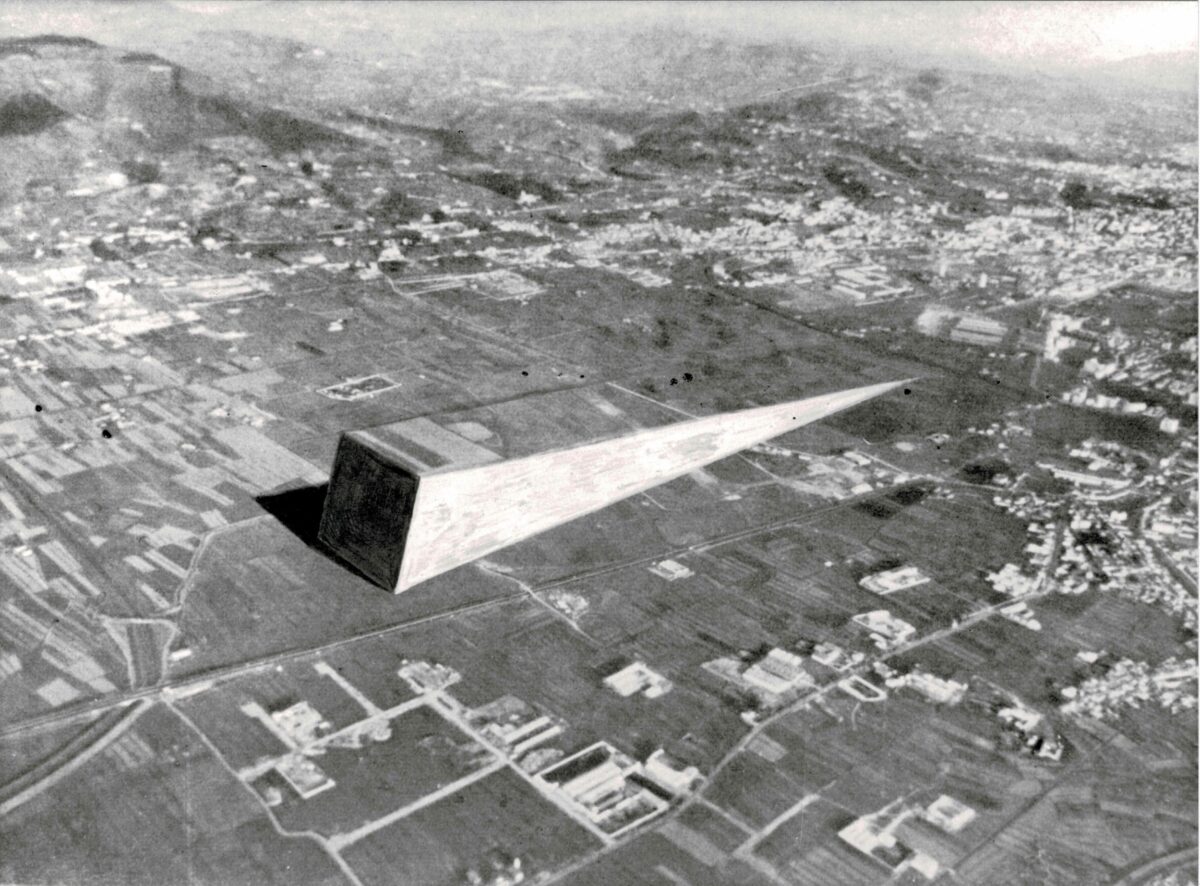

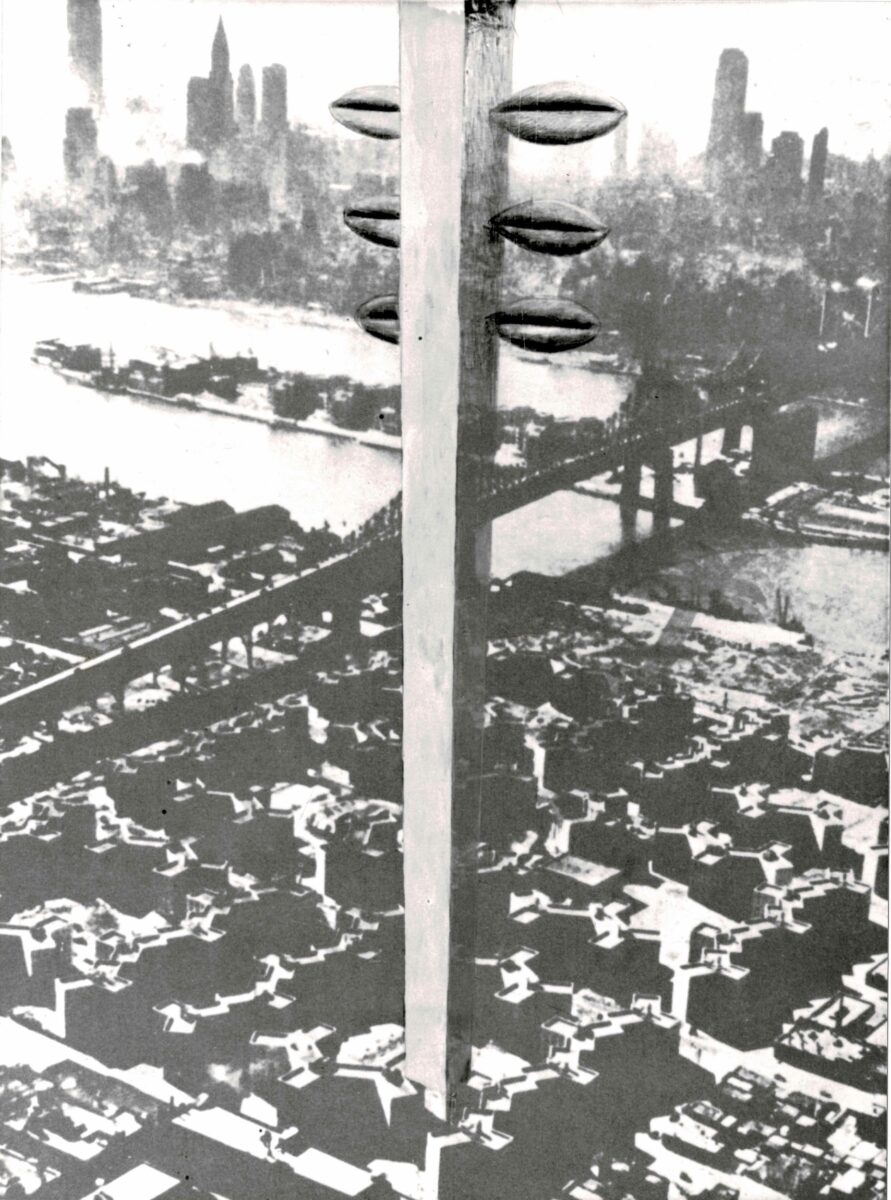

DISCORSI PER IMMAGINI & FOTOMONTAGGI URBANI, 1969

‘Discorsi per immagini’ (‘Discourses for images’) were published in April of 1969 in both Domus, n.481 and L’Architecture d’aujourd’hui, n.145. They are a series of photomontages which critique the architectural discipline’s historical self-placement. The montages are purposefully excessive interventions into cities and terrains—such as the insertion of gargantuan walls across Berlin or the towering plant skyscraper that grows out of New York—pushing the promotion of historical typology, that of Louis Kahn and the Tendenza School, to its absurd limit. Through the narrative tool of visual paradox, Archizoom aimed to subvert the contemporary written manifestos of architecture and thus call for a dissolution of the discipline. The title, ‘Discorsi per immagini,’ was taken from Germano Celant’s 1969 book Earth Works regarding his reflections on the dissolution of the art discipline in Land art and Arte povera.

PUBLICATIONS & POSTER

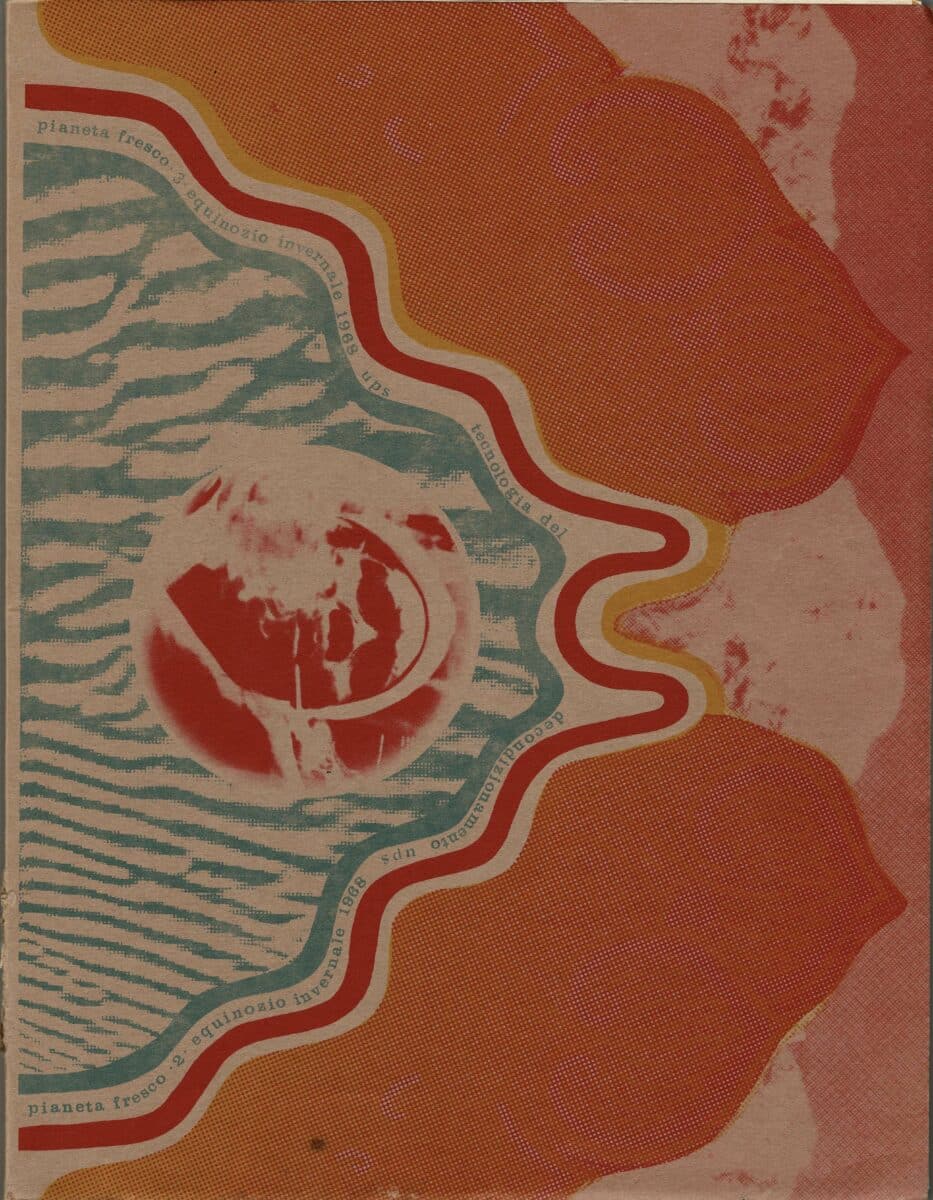

PIANETA FRESCO N.2/3, 1968

Fernanda Pivano and Ettore Sottsass’ Pianeta Fresco ⅔ : Tecnologia del decondizionamento (‘technology of deconditioning’) was released in the ‘winter equinox’ of 1968. It was printed in a small run of 275 copies by their publishing house, Edition East 128. It promoted the Beat movement and its topics of interest: the rejection of authority, pacifism, and spiritualism, among others. Directed by Pivano, the magazine includes her translation work of many American Beat poets, including the writings of Allen Ginsburg, yet she also nurtures Milanese literary talents like Gianni Milano and Renzo Freschi. Alongside these texts, the publication explores radical art and design, experimenting with psychedelic imagery inspired by other publications like the San Francisco Oracle. Designed by Sottsass, it pushes the medium of the magazine as a sensory experience, it is non-linear and rethinks the hierarchy of text and image. This edition at Drawing Matter features two of Archizoom’s works, ‘Teatro impossibile’ and ‘Trucchi’, littered throughout the publication and dizzyingly placed in different orientations.

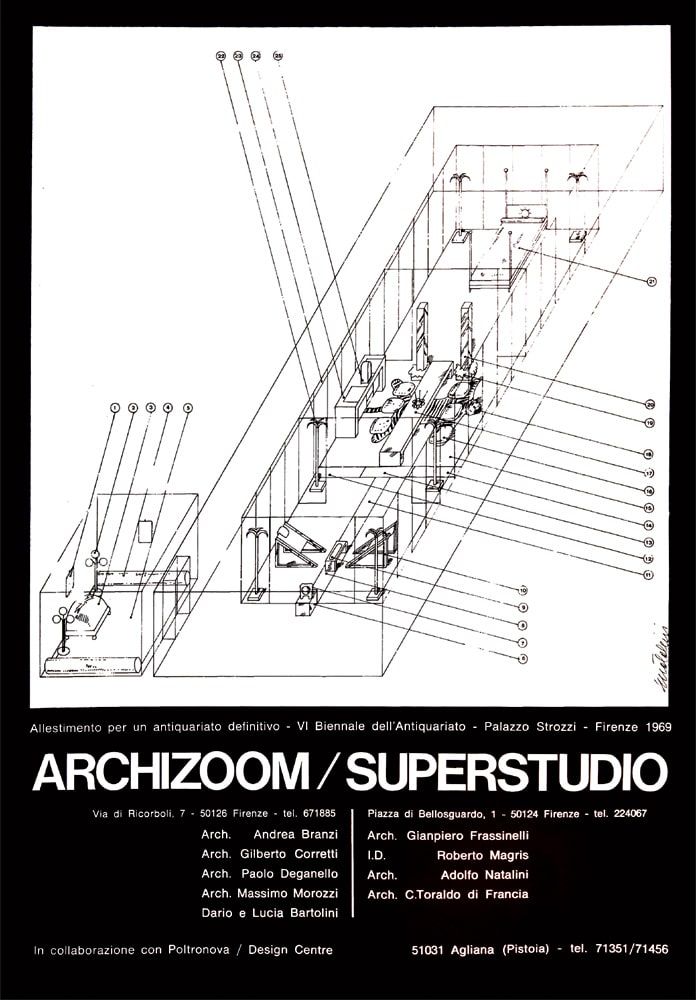

EXHIBITION POSTER, VI BIENNALE DELL’ ANTIQUARIATO, 1969

Poster for the joint exhibition of Archizoom and Superstudio, in collaboration with Poltronova at the VI Antiques Biennial, held at Palazzo Strozzi, Florence in 1969. It features a drawing for the project ‘Allestimento per un antiquariato definitivo’ (‘setting up for a definitive antiques exhibition’). Each piece of furniture in the axonometric drawing is pulled out with a number, although without a key. The objects present in the space are the previous designs of both groups, the mirrored columns and tiger rug of Superstudio, and the ‘dream beds’, ‘Sanremo’ floor lamps, and ‘Mies chair’ of Archizoom. The poster is signed by Adolfo Natalini.

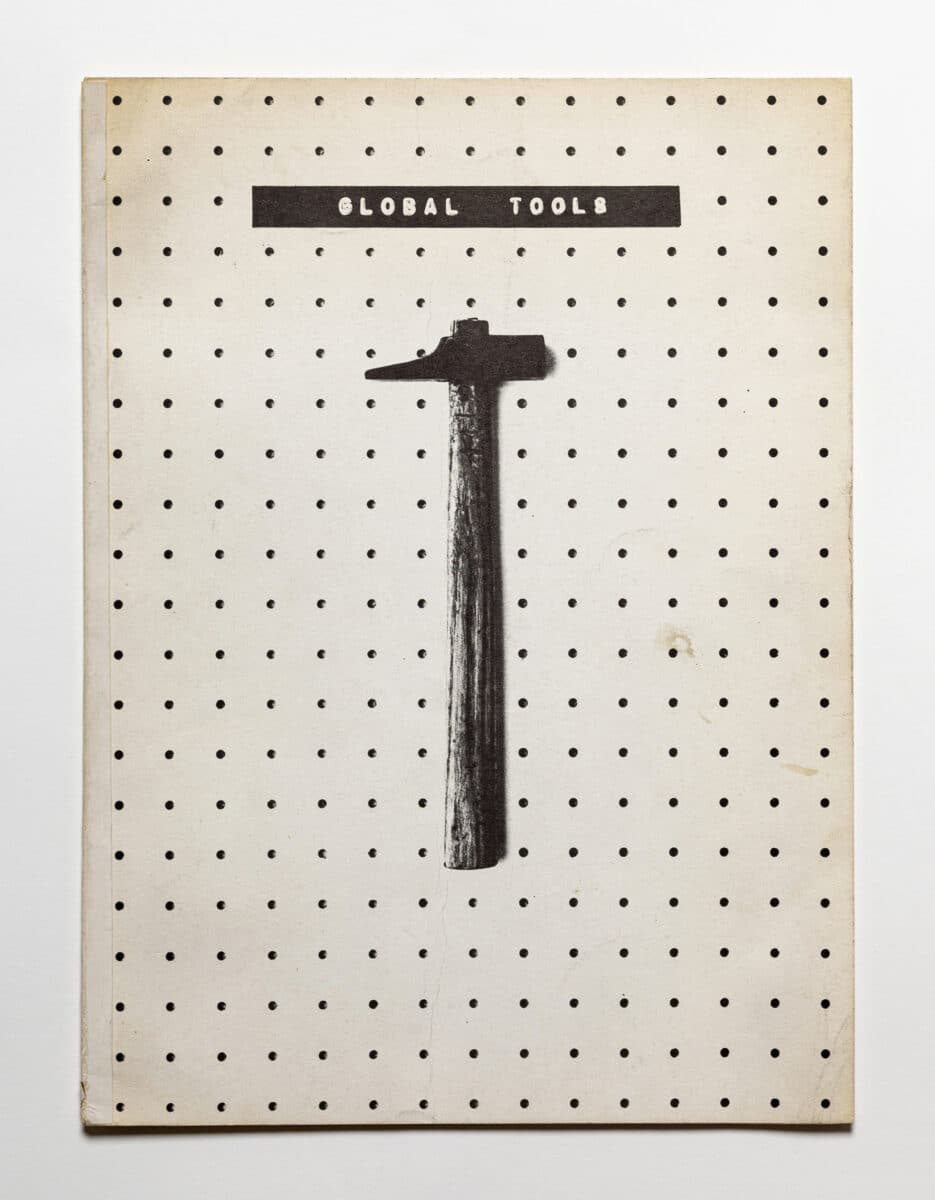

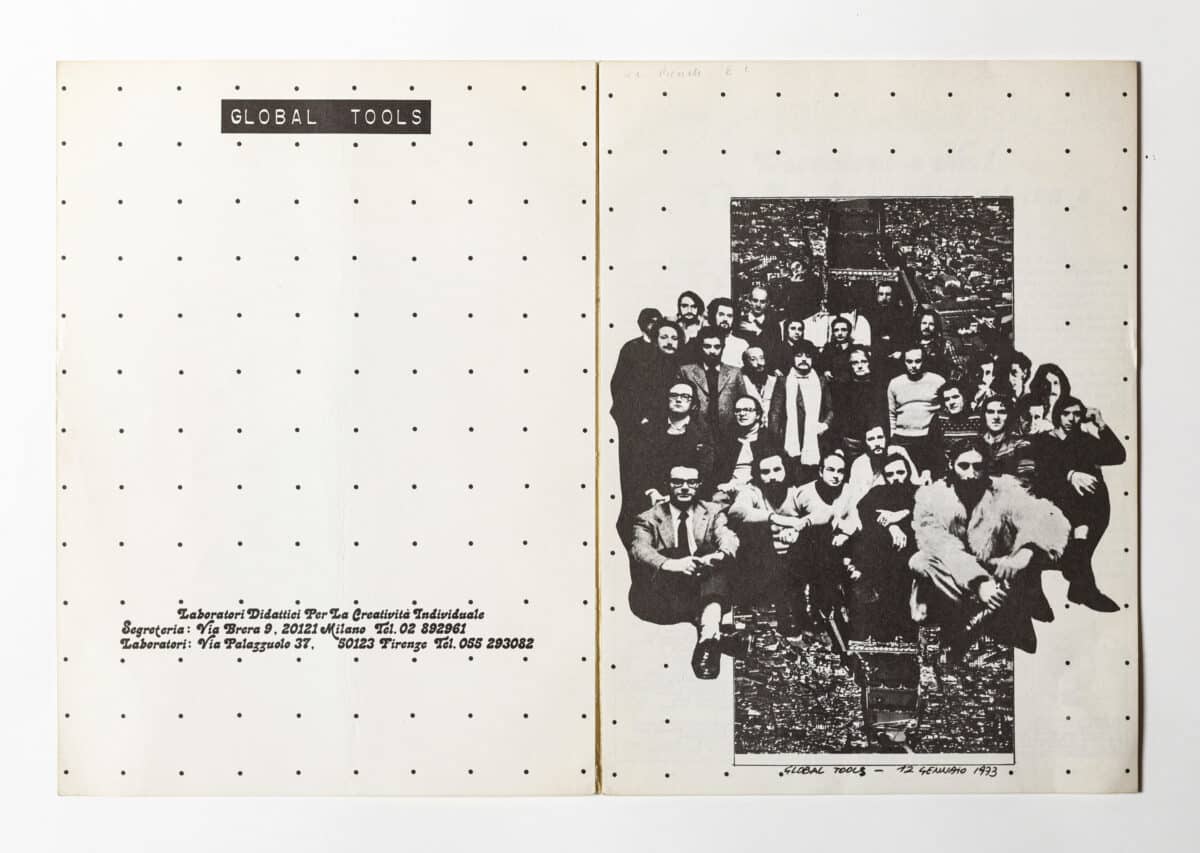

GLOBAL TOOLS, N.1, 1974

Global Tools was formed at the editorial offices of Casabella—at the time directed by Alessandro Mendini— on the 12th January 1973 by a collective of architects, designers, thinkers, and artists, which included Andrea Branzi, Ettore Sottsass Jr., Superstudio, UFO, Franco Vaccari, Giuseppe Chiari, and Germano Celant, among many others. It was a multidisciplinary and experimental program of design education inspired by the work of Victor Papenek and Stewart Brand’s Whole Earth Catalog, as well as Ivan Illich’s Deschooling Society. Their pedagogy was conceived as a ‘diffuse system of laboratories’—workshops that would promote ‘the study and use of natural technical materials and their relative behavioural characteristics […] to stimulate the free development of individual creativity.’ The workshops started in Florence, but spread across Italy from 1973 until 1975.

‘Bulletins’ would be published regarding the teaching programme, group research projects, and the organisation of further events. The edition held in the Drawing Matter collection is the first of these ‘bulletins’ published by Casabella and Rassegna. It contains five ‘documents’ and a conversation, alongside biographies of all group members. The documents outlined the collective and their purpose, contextualised the school’s approach to craft, stating the agenda of activities for their first workshop in September 1974, and lists the group members leading each session. Branzi was part of the ‘construction’ workshop, alongside Sottsass, Dalisi, Alison and Fabro. The conversation is a discussion on the project, an informal manifesto; it was held between Lapo Binazzi, Andrea Branzi, Germano Celant, Ugo La Pietra, Alessandro Mendini, Adolfo Natalini, Franco Raggi, and Ettore Sottsass Jr..

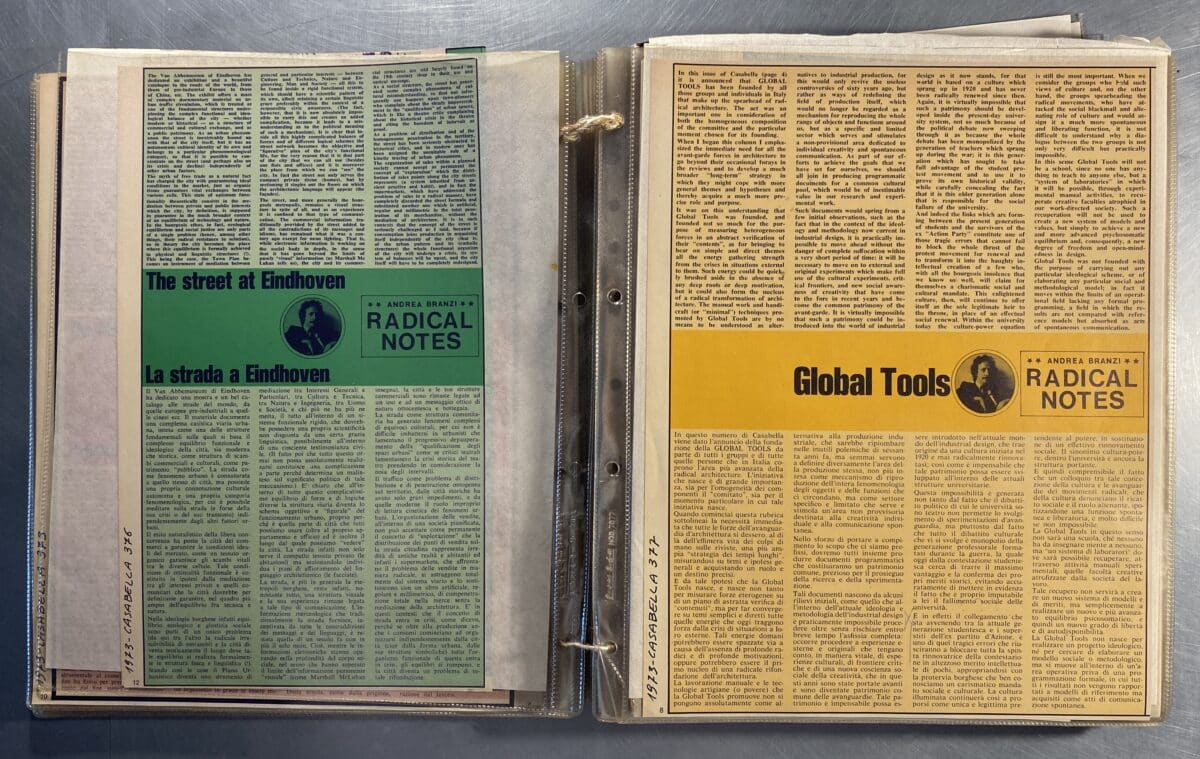

CASABELLA, 1972-1975

Drawing Matter holds a bound laminated copy of all Branzi’s ‘Radical Notes’, which is appended by additional articles he wrote for Casabella. His column ‘Radical Notes’ was produced under the editorship of Alessandro Mendini, and was a space defined by Branzi, to write on the historical and social functions of the avant-garde movement. He desired to forge a language to analyse the many disparate groups under the umbrella of the ‘avant-garde’. He determined the movement as a ‘threshold phenomenon’ where change was brought through multiple individual voices rather than one collective whole. The Drawing Matter collection also has six copies of Casabella which range sporadically from October 1972 to May 1975 and feature Andrea Branzi’s column ‘Radical Notes’.

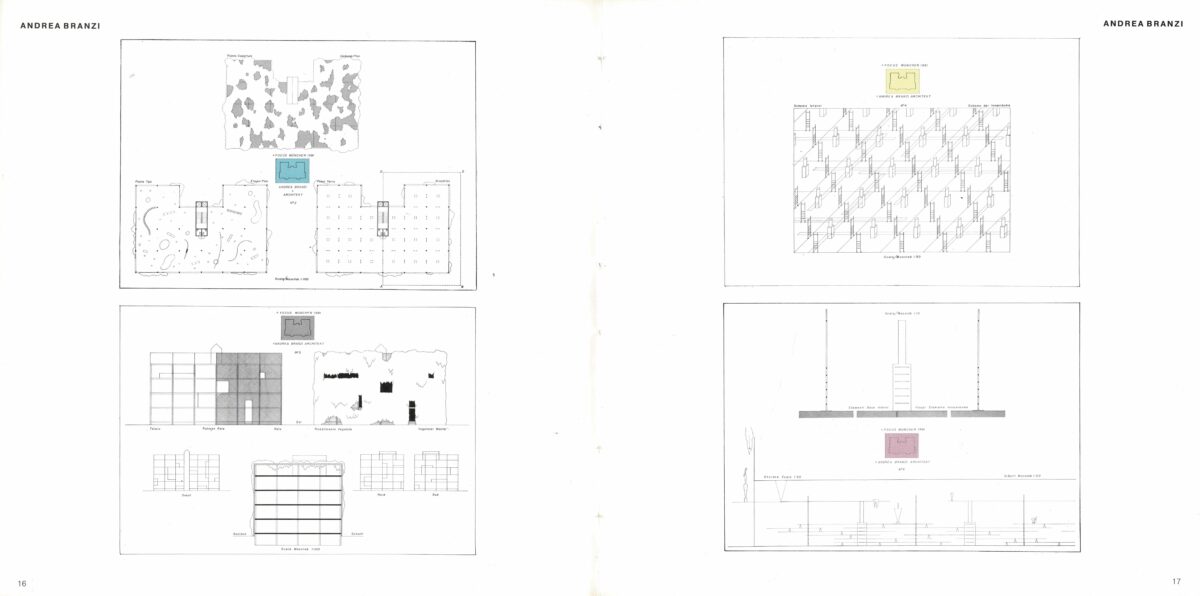

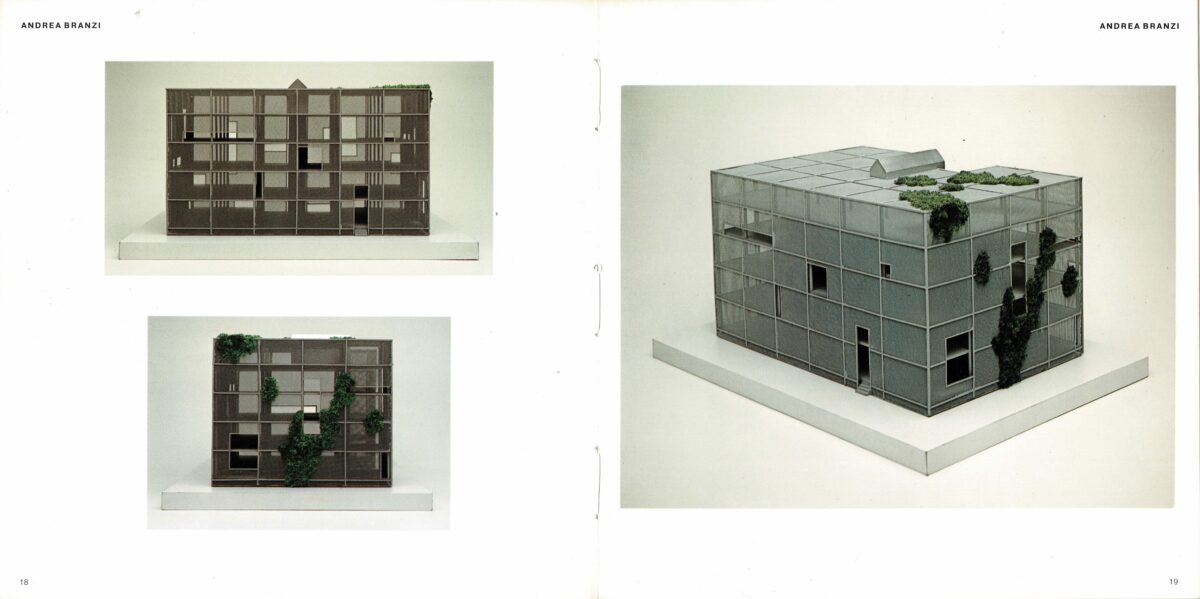

CASA DELLA FALSITA, 1982

The Casa Della Falsità (‘the house of falsehood’) was an exhibition of 11 invited proposals for the transformation of Peter Pfeiffer’s house on Leopoldstrasse in Munich. Andrea Branzi was one of those invited alongside Opera, Zaha Hadid, Trix and Robert Haussmann, Haus Rucker Co., Alessandro Mendini, Bruno Minardi, Robert Maria Stieg, Studio Alcymia, Stefan Wewerka, and Peter Wilson. In Branzi’s proposal plants would assume no definite form as they grew over the facades of the Falsità house. All eleven proposals were printed in this catalogue for the exhibition held at Munich’s Focus Gallery, in 1982. Drawing Matter also holds the competition drawings from Peter Wilson.

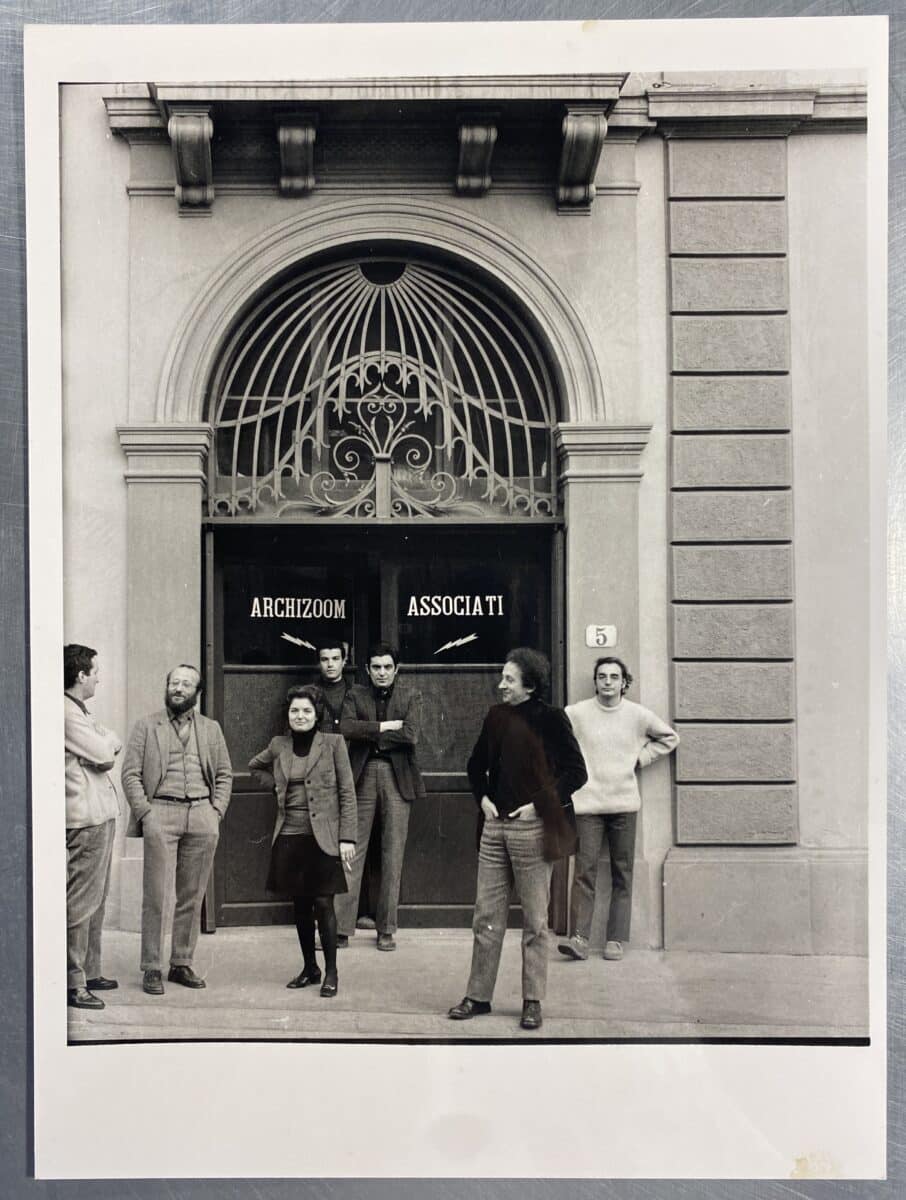

ASSORTED PORTRAITS

Drawing Matter holds multiple portraits of Archizoom. The earliest was taken in the grounds of Villa Strozzi, Florence, where the group rented their first office (DMC 2738.2.1). The photo taken by Dario Bartolini shows Massimo Morozzi, Andrea Branzi, Paolo Deganello, and Gilberto Corretti wearing costumes as they posed with a stone bust. Another was taken in front of their next office in via di Ricorboli, Florence (DMC 2738.2.2); it is a group portrait of Dario Bartolini, Paolo Deganello, Lucia Bartolini, Natalino Torniai (a collaborator of Archizoom), Massimo Morozzi, Andrea Branzi, and Gilberto Corretti. The next shows members of the group lying inside their 1968 installation for the XIV Triennial di Milano, ‘Centro di Cospirazione Eclettica’ (‘Centre for Eclectic Conspiracy’)(DMC 2738.2.3). Gilberto Corretti, Massimo Morozzi, Cristina Morozzi, and Andrea Branzi lie on a large ‘Turkish style bed’ surrounded by black drapes with a monument dedicated to Malcolm X at its centre.

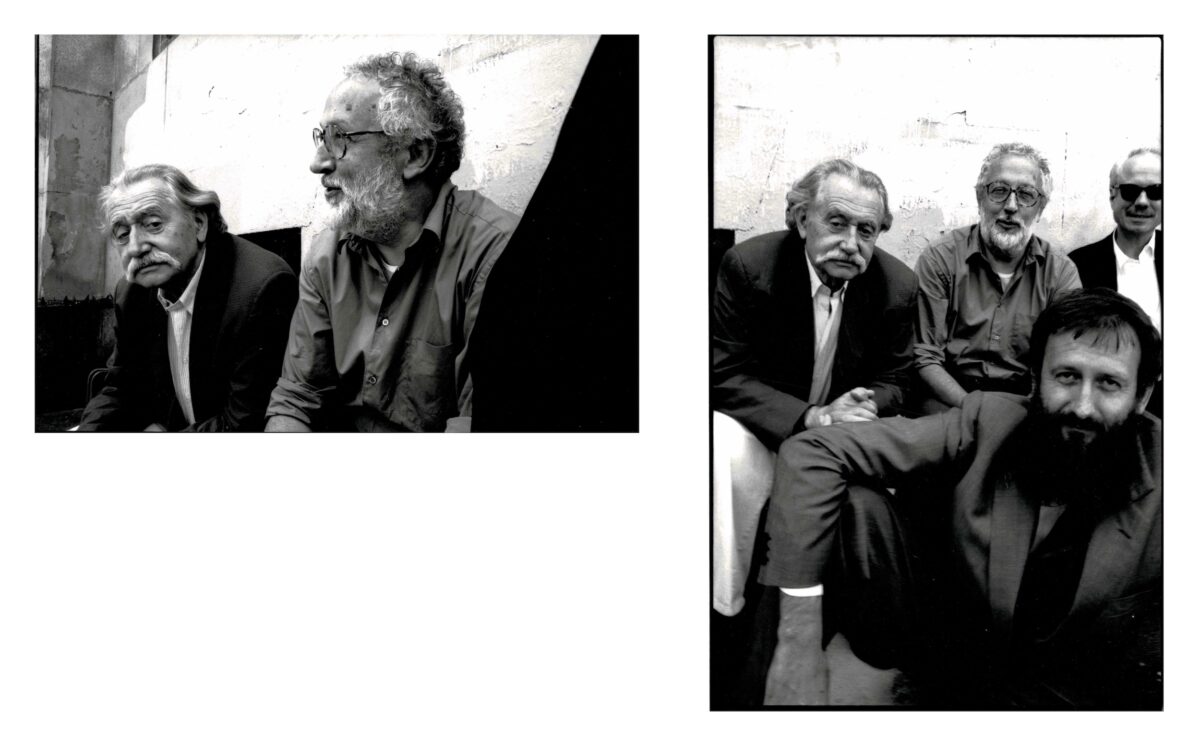

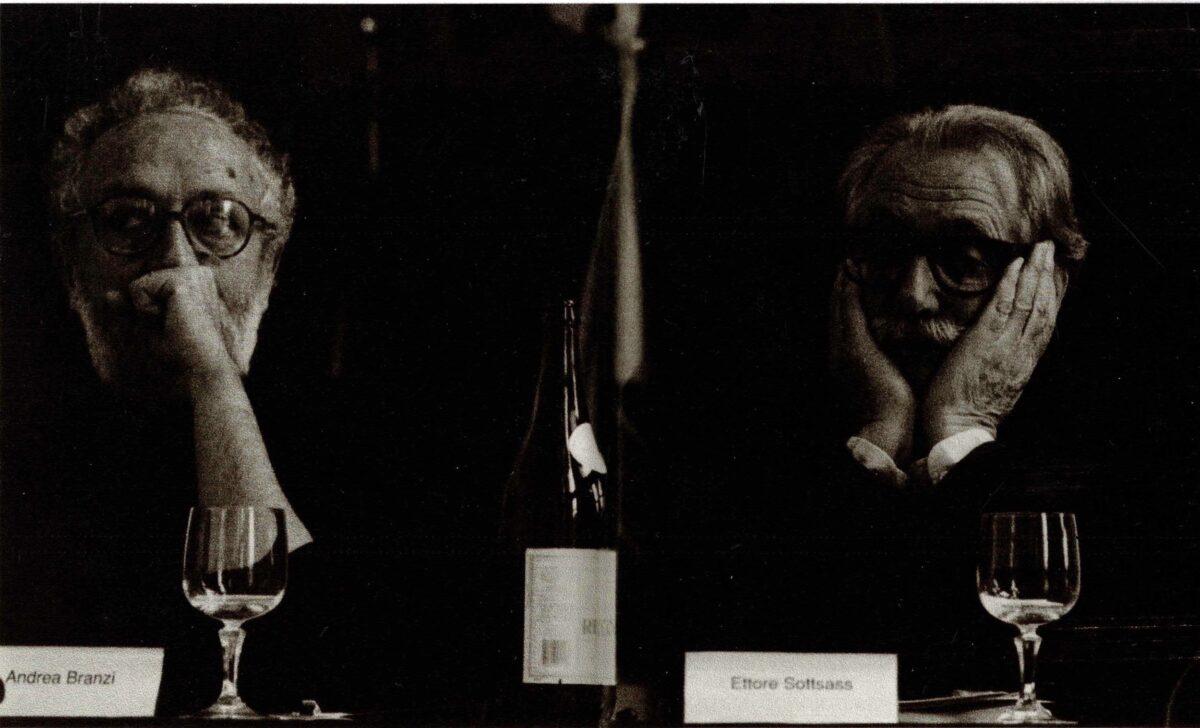

Drawing Matter also holds later portraits of Andrea Branzi. Two taken in 1991 with Ettore Sottsass, including one with Rolf Fehlbaum and Michele de Lucchi, while working on ‘Citizen Office’ for furniture company Vitra. The most recent portrait of Andrea Branzi held in the Drawing Matter collection is possibly from the Domus conference in April 2004, tied to the launch of Domus n.869 in which Branzi and Ettore Sottsass Jr., alongside Alessandro Mendini, Vico Magistretti, and Enzo Mari spoke.

PAPERS

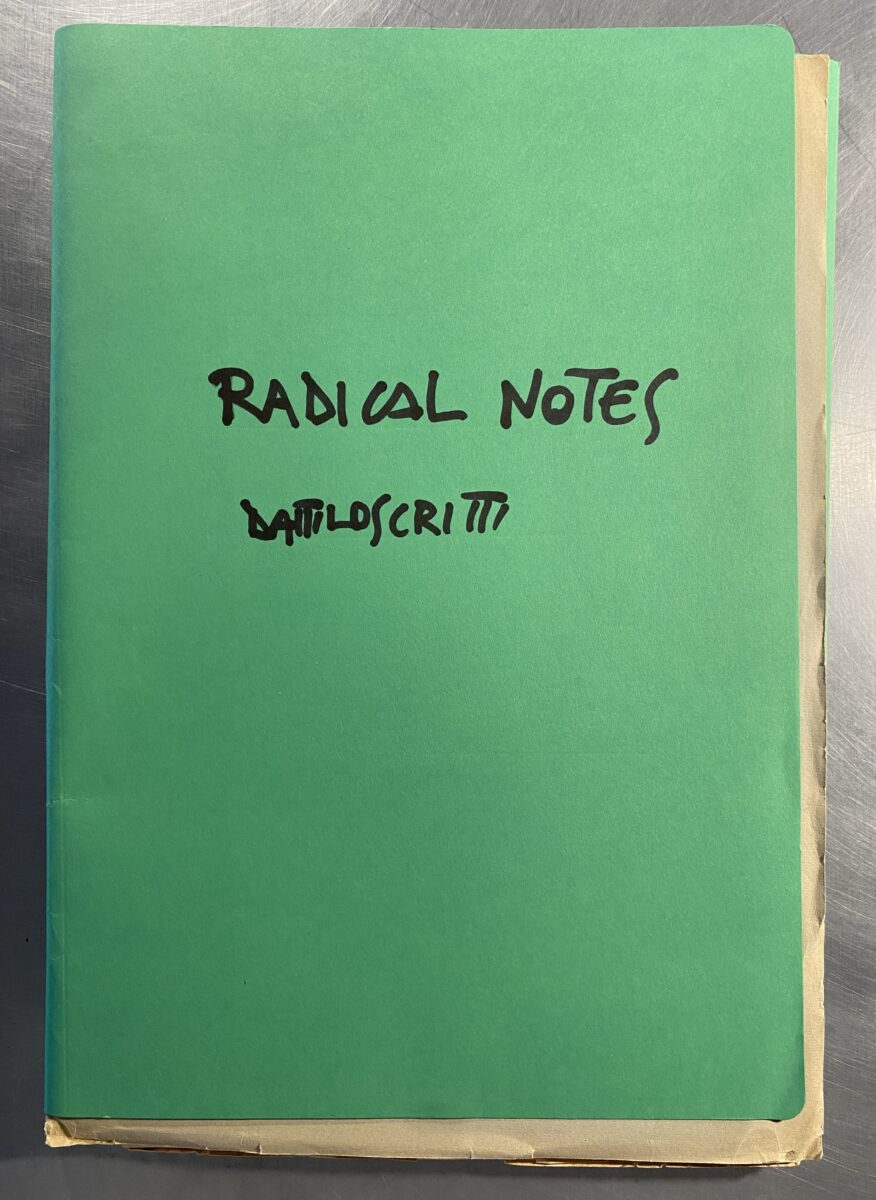

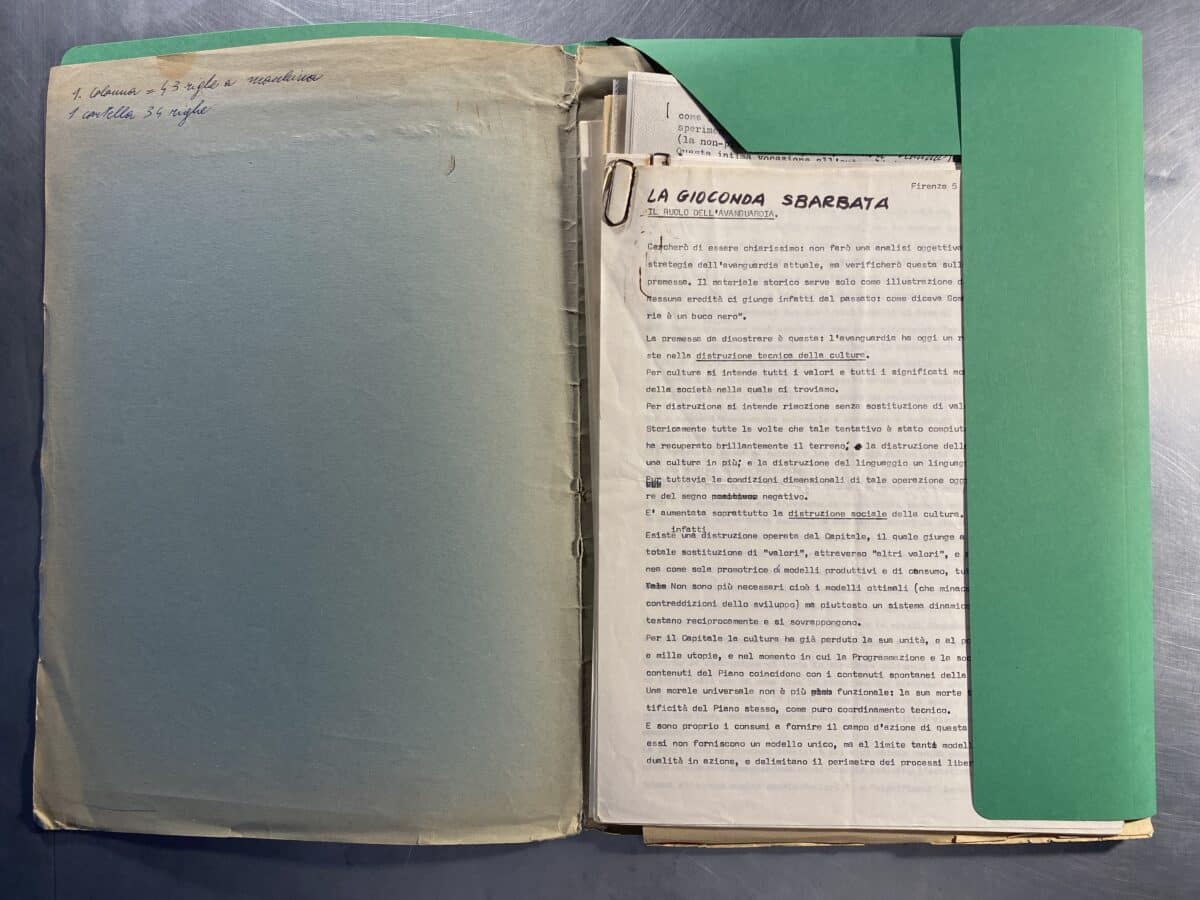

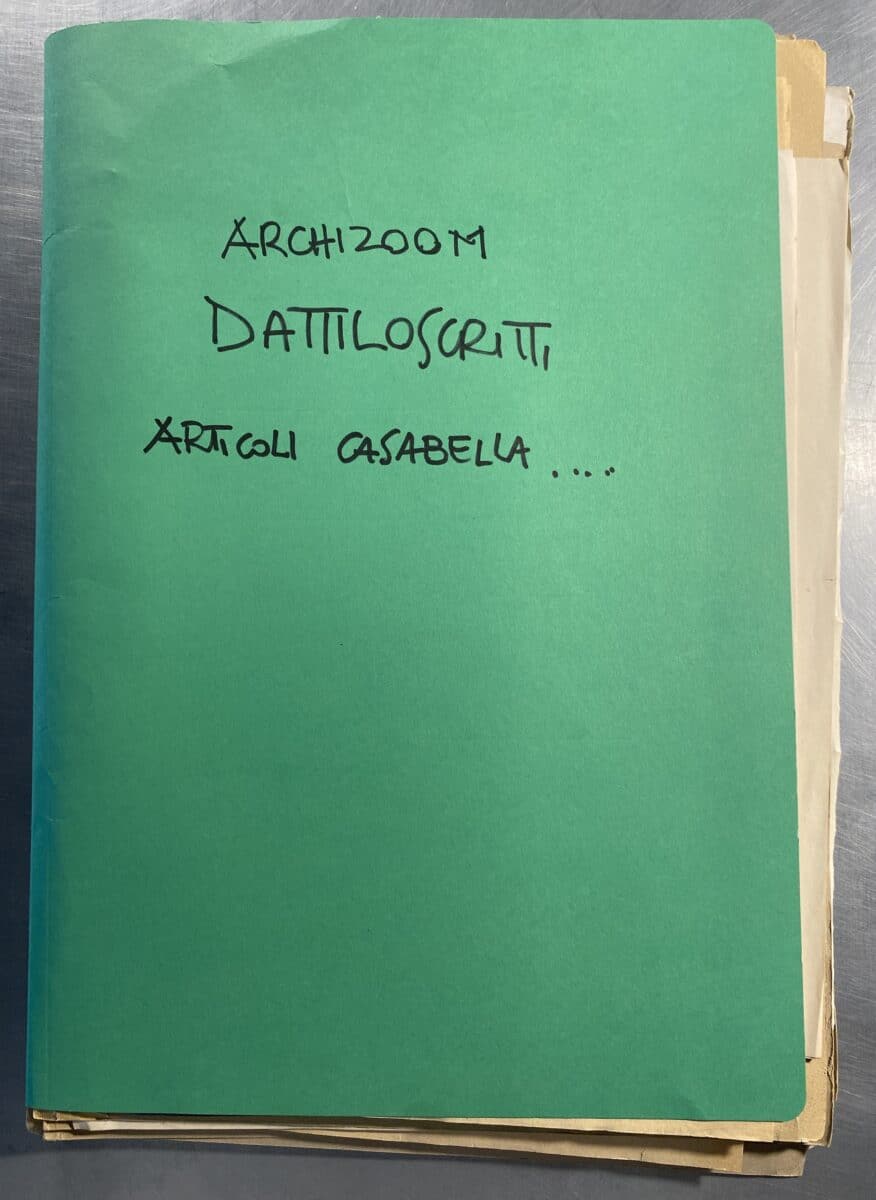

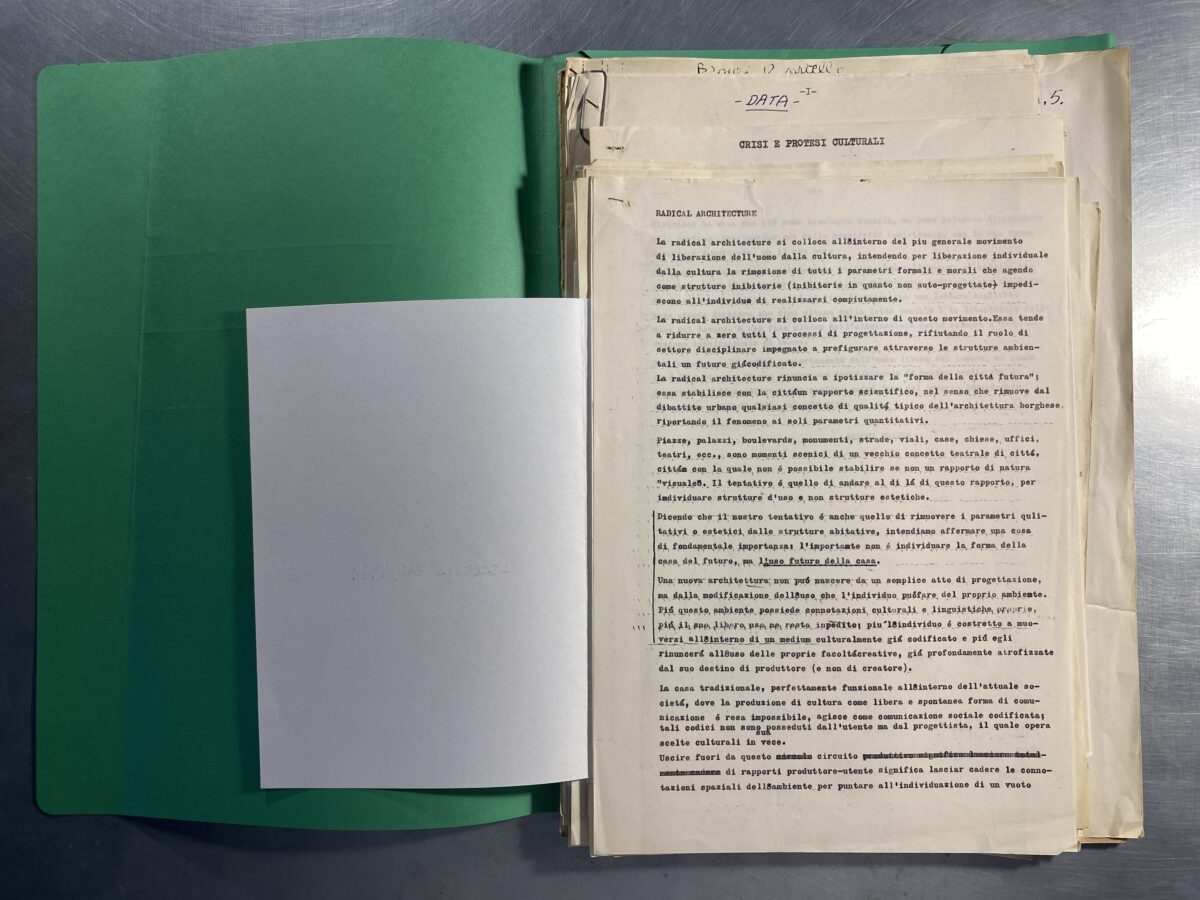

The following papers came divided into these green folders with titles from the office of Andrea Branzi. The typescripts are working documents—typed pages are annotated by hand or amended through collages of additional material.

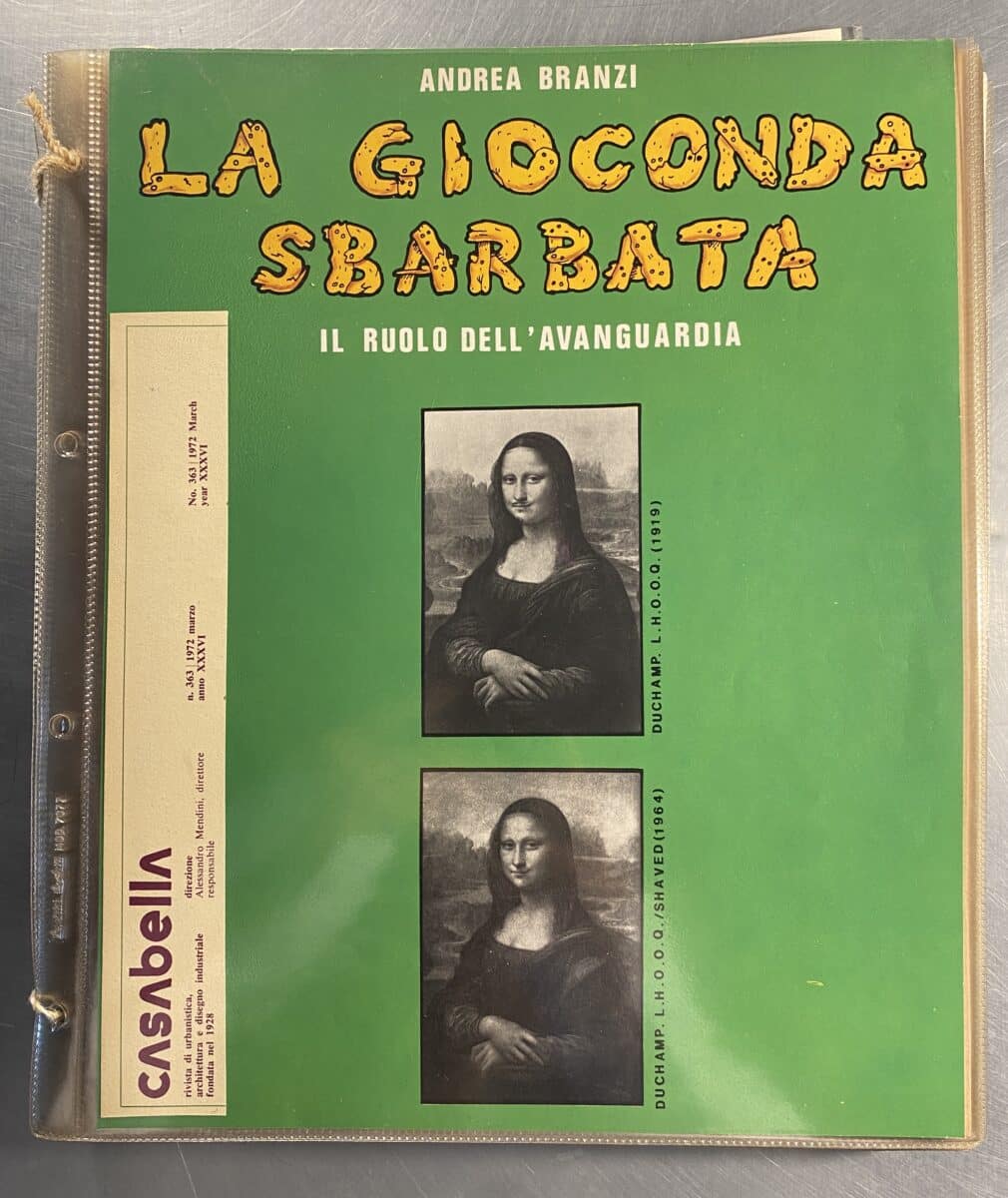

RADICAL NOTES: DATTILOSCRITTI

Three typescripts for Andrea Branzi’s ‘Radical Notes’ column in Casabella. They are for the opening essays of the column, ‘La Gioconda sbarbata’ (‘The shaved Mona Lisa’), ‘L’Africa è vicina’ (‘Africa is near’), and ‘Abitare è facile’ (‘Living is easy’), and sit under the collective title, ‘Il ruolo dell’avanguardia’ (‘The role of the avantguard’). They were published successively in Casabella n.363 (March), n.364 (April), and n.365 (May) in 1972. Each essay also had a dedicated frontispiece to accompany the text.

ARCHIZOOM: DATTILOSCRITTI & ARTICOLI CASABELLA …

Typescripts of Archizoom writings for various magazines. The texts could be divided into four categories: for exhibitions or events, reflections on projects, unknown writings, and an essay for Branzi’s ‘Radical Notes’ column, ‘Il sogno del villaggio’ (‘The dream of the village’) for Casabella n.371 (1972).

For exhibitions and events, it includes ‘Il Pollo di marmo’ (‘the marble chicken’) written for the XIV Triennale di Milano (1968) and ‘S-Space Festival’ written for Gruppo 9999’s experimental dance club, Space Electronic, which opened in Florence in 1969. For reflections on projects or practice, we find a text for No-Stop City in Italian and English; ‘Residential Parkings’ for Domus n.496 (1971), in both Italian and French; an English copy of ‘Teatri Impossibili’ for Pianeta Fresco, n.⅔ (1968); an English text called ‘By strength of things to thing, for strength’ for Domus; ‘Le stanze vuote e i gazebos’ for Domus, n.462 (1968) in both Italian and English; an English copy of ‘L’Apprendista Stregone’ for IN Magazine; and ‘The Destruction of Objects’ also for IN Magazine (March/June 1971). Alongside these it includes writings which do not specify their place of publication; ‘Relazione per il concorso internazionale nuova università Firenze’ (‘Report for the international competition new university Florence’), ‘Non Rintracciato’ (‘Untraced’), ‘Due Allestimenti Didattica a Roma e a Firenze’ (‘Two didactic installations in Rome and Florence’), and ‘La Città immorale’ (‘The immoral city’).

ARCHIZOOM IDEOLOGIA E TEORIA DELLA METROPOLI – CITTA CATENA DI MONTAGGIO DEL SOCIALE

The folder is named ‘Città Catena di Montaggio del sociale, ideologia e teoria della metropoli’ (‘Assembly Line City of the Social, Ideology and Theory of the Metropolis’); it is written in both French and English. It was published in Casabella n.350-351 (1970).

BRANZI ARTICOLI VARI

As its title suggests, this folder contains various articles written by Andrea Branzi. It includes the following two texts for Casabella, ‘Crisi e Protesi Culturali’ for n.385 (1974) and ‘Architettura radicale’ for n.386 (1974). It features two texts for Modo, ‘Gio Ponti’ and ‘Cultura popolare’ (‘Popular Culture’) for December 1972. Three of the texts refer to other publications, competition entries, or exhibitions; an interview with Ettore Sottsass Jr. for L’espresso around La Triennale di Milano; an article for La Repubblica, on the Portuguese avant-garde; and writing for the competition of ‘La mostra dell’artigianato’ (‘The artisans exhibition’) hosted at the Fortezza da Basso in Florence in 1971. The other articles’ place of publication is not specified: ‘Superfici Profonde’ (‘Deep Surfaces’), ‘Viaggio in Vienna’ (‘Trip to Vienna’) (1978), ‘Tempo Morto’ (‘Dead time’), ‘Pinocchio Partigiano: il paese dei Balocchi Di Zanuso e Consagra a Collodi’ (‘Partisan Pinocchio: Toyland By Zanuso and Consagra in Collodi’), ‘Dalla Tecnica Povera alla Tecnologia semplice’ (‘From Poor Technique to Simple Technology’) (September 1974), ‘Data’ (‘Date’), ‘Scuola di Firenze’ (‘School of Florence’), and ‘Relazione Parigi, Tavola Rotunda, italiano, Francese, e Inglese: l’anti design non esiste’ (‘Paris round table report, Italian, French, and English: Anti-Design Doesn’t Exist’).

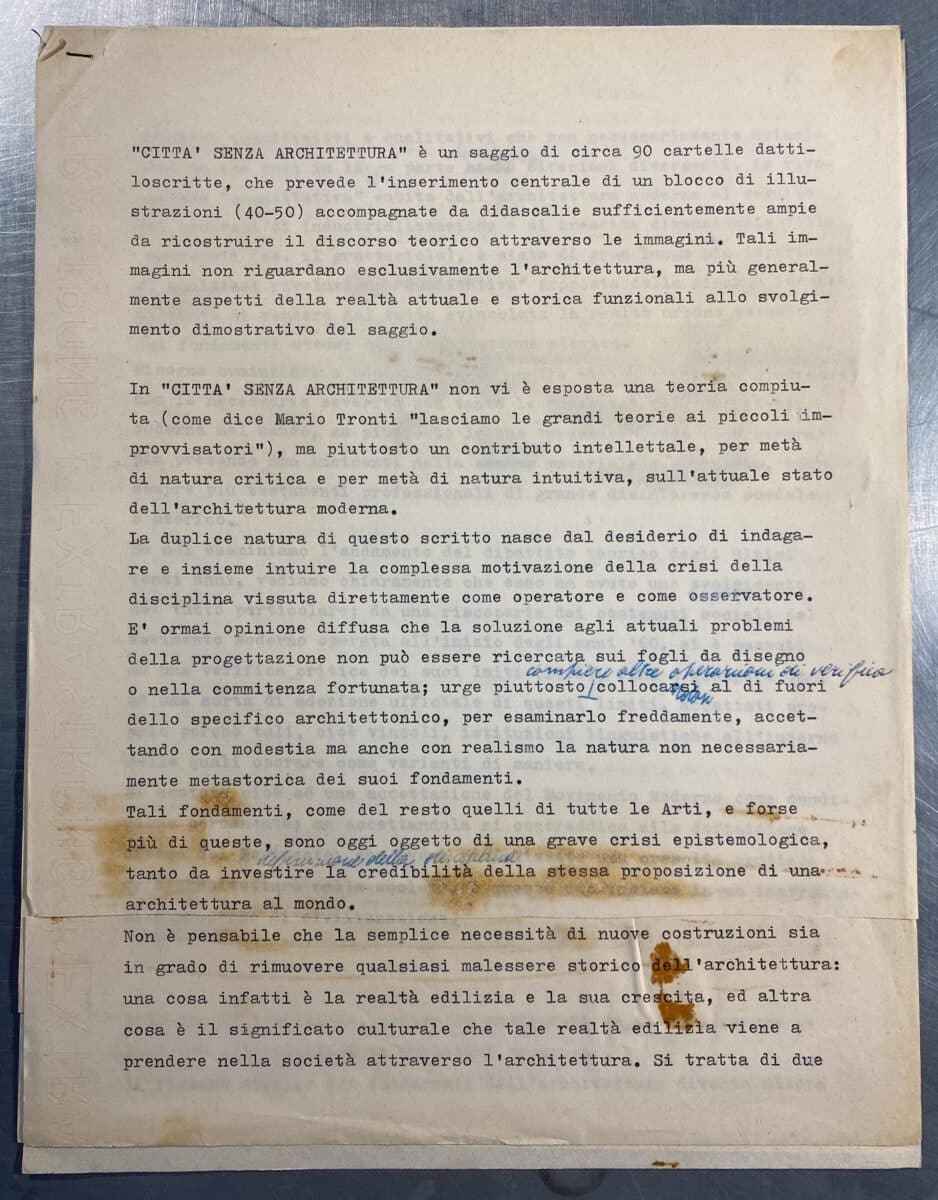

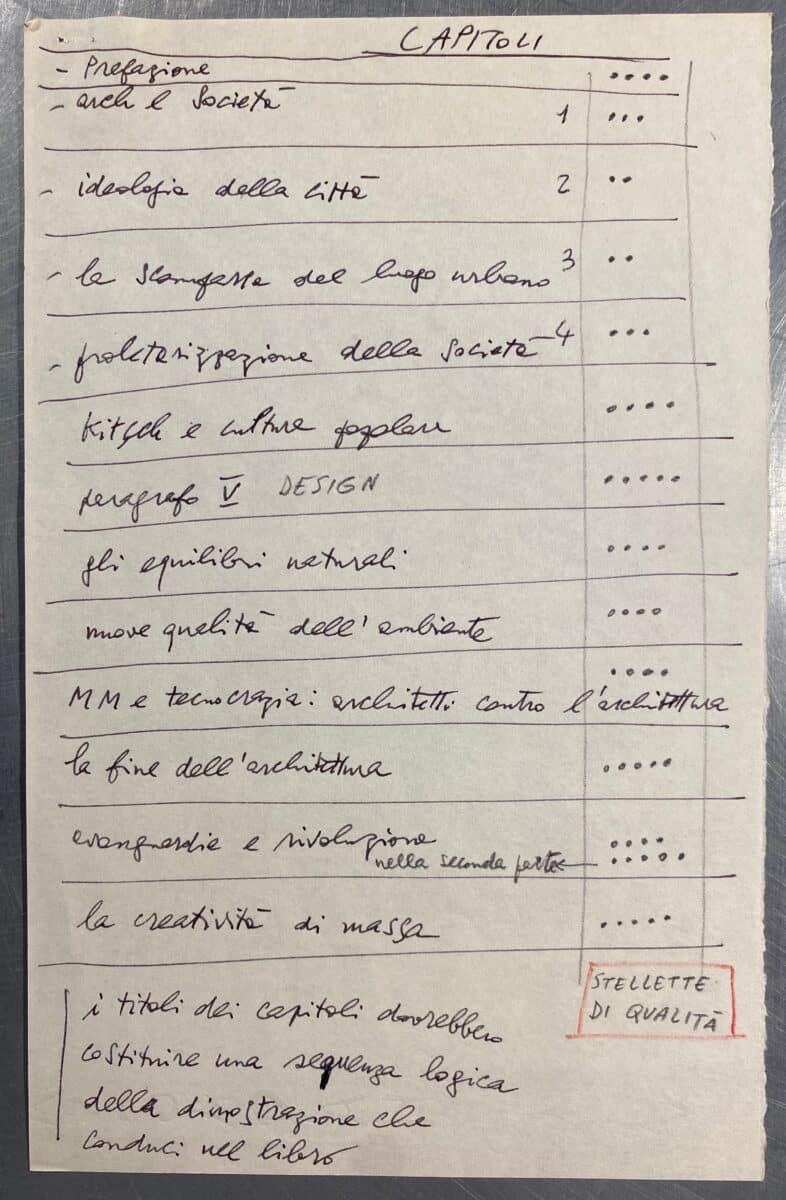

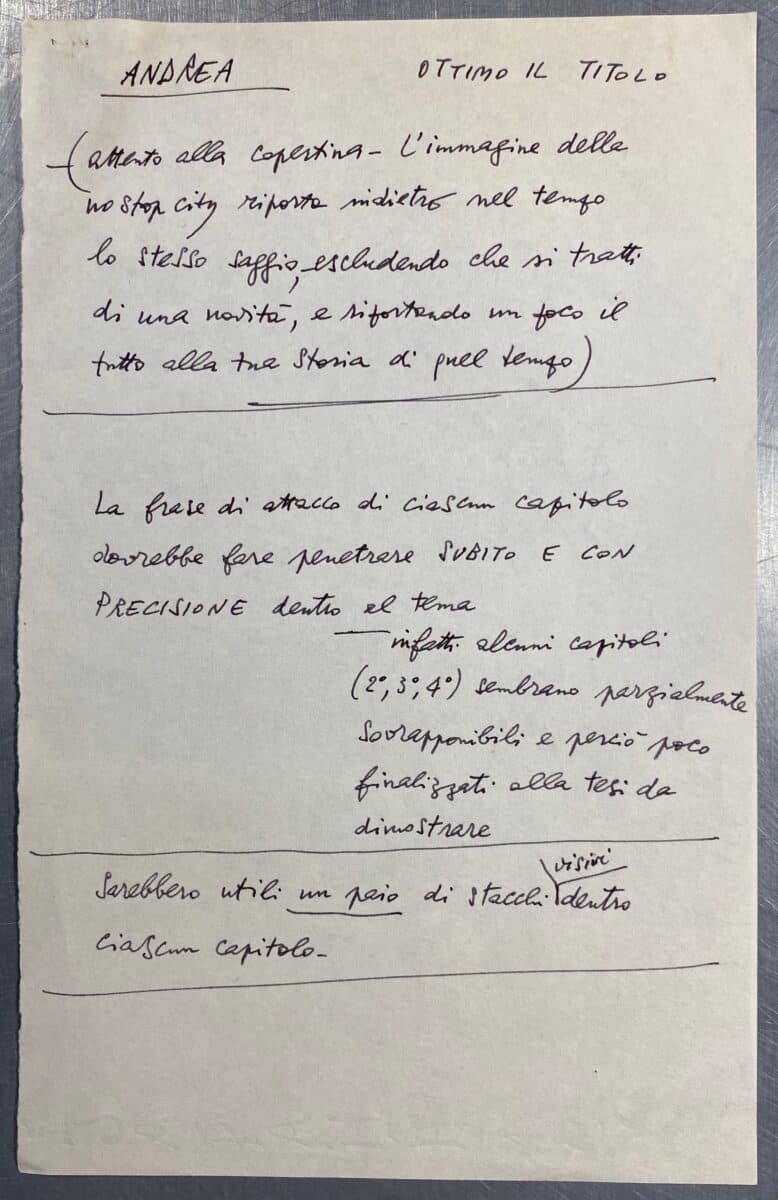

DRAFT BOOK, CITTÀ SENZA ARCHITETTURA

The drafts for Andrea Branzi’s unpublished book, provisionally titled Città senza architettura (City without architecture), are divided into six folders of revisions. The publication would consist of a series of essays on 90 type-written pages with a central block of illustrations. Although the exact order of the folders is uncertain, an editor’s bundle of notes reveals some of the processes taking place in the papers: the trimming of paragraphs and the division of texts into shorter chapters. Amusingly the editor even ranks the chapter’s quality with stars. While the date of the drafts is unknown, the ideas presented and a specific editorial comment—that using Archizoom’s No-Stop City on the cover would remind the reader of something produced long ago—suggest that it is possibly from the late 1970s or 1980s. To some degree, the drafts for Città senza architettura could be seen as a precursor to his later book Weak and Diffuse Modernity: The World of Projects at the Beginning of the 21st Century (2006), especially for sharing No-Stop City on the cover.

*

The authors of this collection guide would like to warmly acknowledge the brilliant work carried out by Elisa C. Cattaneo in editing Andrea Branzi: E=mc2 The Project in the Age of Relativity published by Actar in 2020.

Additions and amendments are welcomed at editors@drawingmatter.org