Anton Markus Pasing

Münster, March 2024

Mad I cannot be, sane I do not deign to be, neurotic I am.

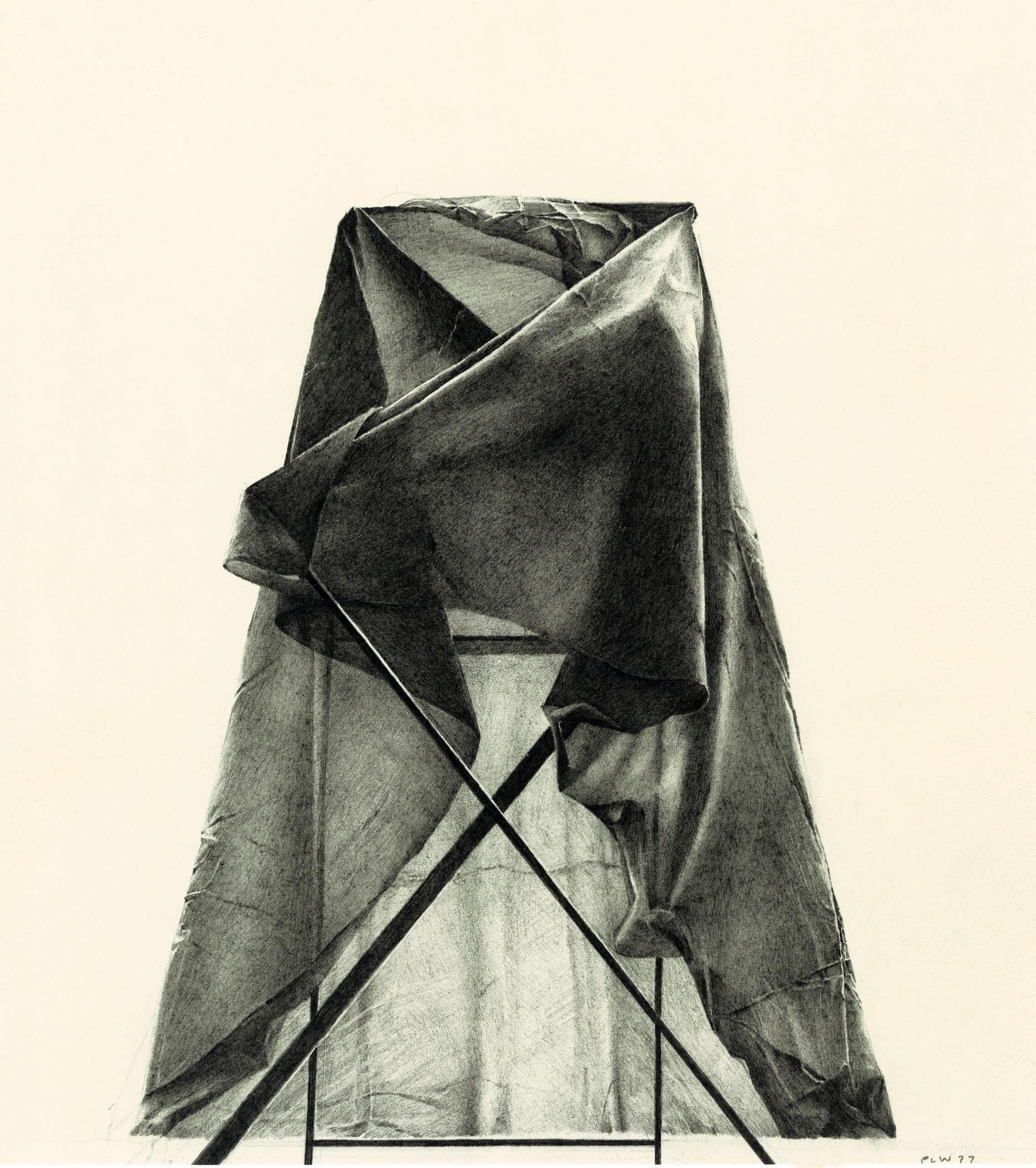

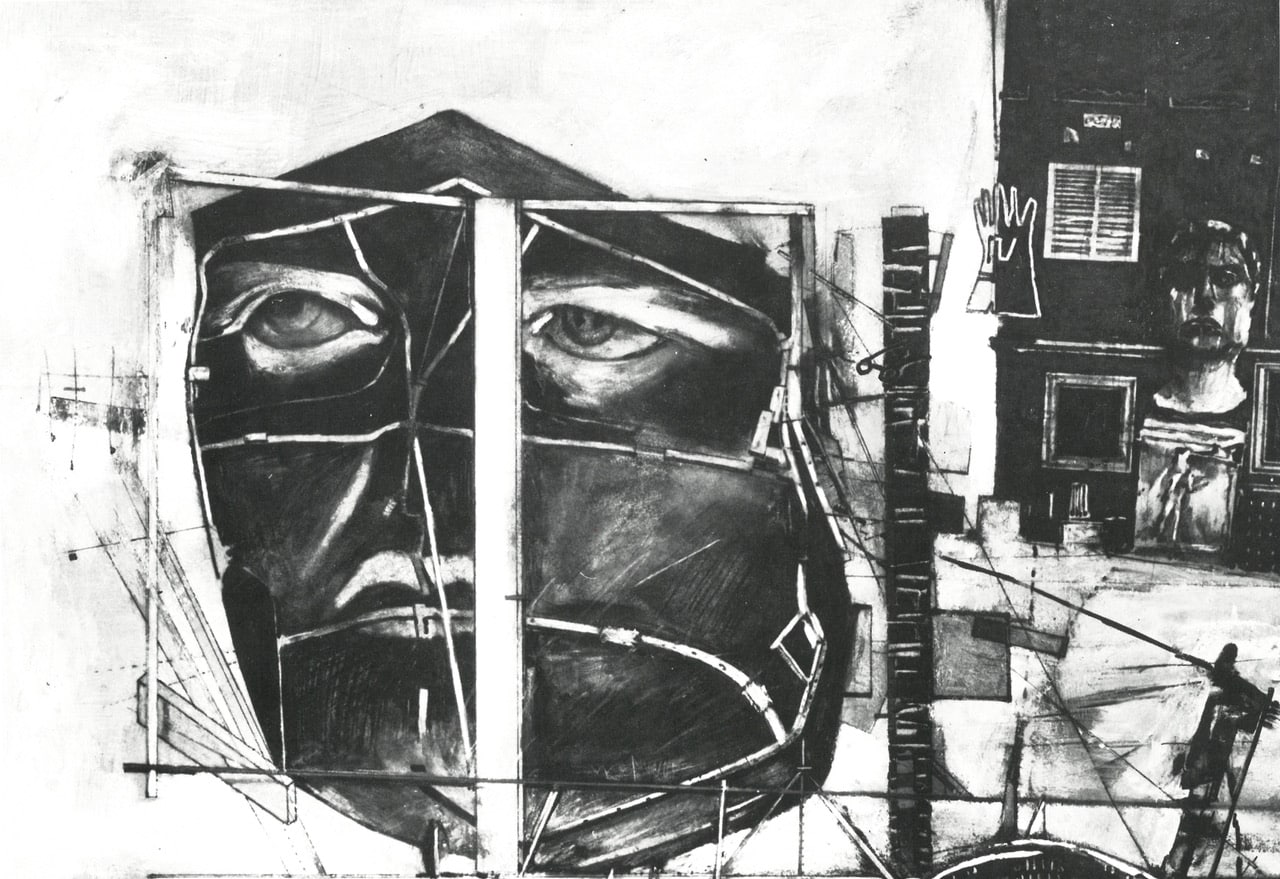

Nearly fifty years ago Nigel Coates writing in my Villa Auto AA exhibition catalogue chose the above quote from Roland Barthes to describe my pathological production of architectural fictions. These were hand-drawn, a medium now being rediscovered by a new generation of digital natives, those whose hands are more accustomed to clutching a mouse than a pencil. Anton Markus Pasing (aka. Remote Control) belongs to an intermediate generation; he is a godfather of the virtual image. It is now appropriate for me to pass on the Barthes reference and to firmly attach it to Pasing. How else could we describe his obsessive and immense oeuvre than a neurotic addiction to multiplicity? Italo Calvino informs us (through his fifth memo on ‘Multiplicity’) that ‘Each life is an encyclopedia, a library, an inventory of objects, a series of styles and everything can be constantly shuffled and recorded in every way conceivable.’ For Pasing the encyclopedia is one of images, and he had the good fortune to be born into the first generation to which digital technology offered the possibility of a constant re-shuffling.

These two books, Unindebted Assumptions Part A and Part B, are a compendium, a taxonomy, an array of images that individually enthral and collectively stun. The original meaning of compendium is an abbreviation, an abridgement, reduced to a small compass (compendious). The OxfordEtymological Dictionary extends this definition to include streamlining. But for Pasing’s neurotic output such reduction is hardly possible, it is his objects, his formal compositions themselves that are often streamlined.

In the history of architecture and design streamliningis associated with superficial styling, a pencil sharpener by Raymond Loewy for example, that William Gibson described as looking like it was designed in a wind tunnel. A post-WWII evolution of ‘high-tech architecture’ also went through a phase of excessive streamlined styling. I am thinking of Future Systems whose pods and blobs evolved from Jan Kaplicky’s time in the Foster office. The pretext for such an architecture is utility. Finely tuned machines for precisely defined functions (e.g. a pod for a lone mountaineer to be suspended in nature) based on an ontology where technology provides the answers, but as Cedric Price said, ‘if technology is the answer, what was the question?’. Today we see technology more as the problem, as the generator of overproduction and overconsumption in wealthy countries. Pasing (although he began as an admirer of Future Systems, also Neal Denari (the Californian designer of helicopter-like architectures) avoids issues of fetishised consumption by fetishising the aesthetics of the architectural object. His objects are designed not so much to be useful but to intimidate—sublime apparitions, almost indifferent to their own material history and equally as coy about their formal composition.

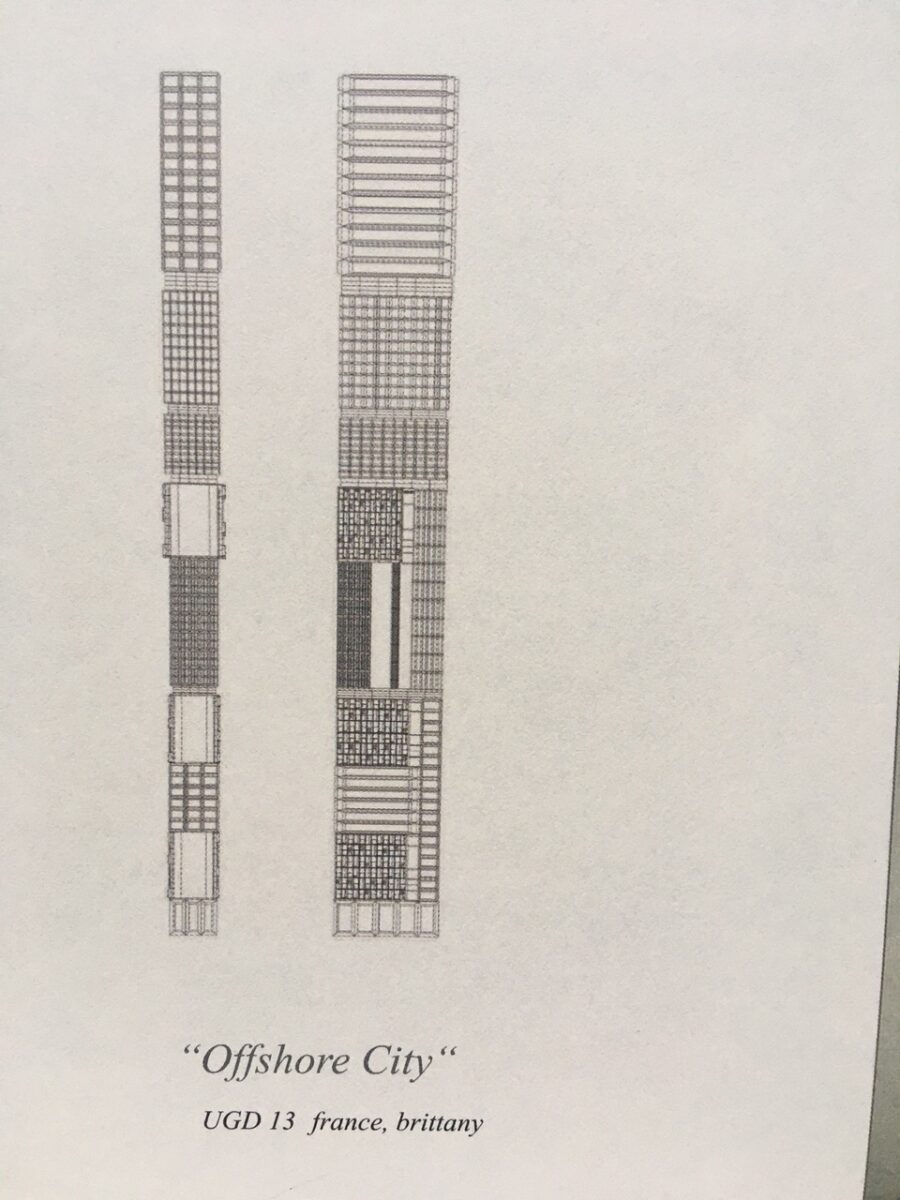

To stretch a point, we could refrain from relegating Pasing’s works to the visionary box, but locate them instead within the genre of architecture. This requires a scrutiny of compositional tropes. Lurking behind or within almost all his hallucinatory mirages is to be found a precise Cartesian volume. We could interpret this disciplinary rigour (e.g. Offshore-City) as the result of Pasing’s time as a student of Oswald Mathias Ungers at the Dusseldorf Kunstakademie. Usefully, the extensive compendium of these two volumes is sprinkled with precise plan and elevation linework, the DNA skeletons of mega-forms destined to subsequently (once rendered or fractured) hover in sandstorms or above Dutch polders.

From Piranesi to Joseph Gandy to Corbusier’s Ville Radieuse there has always been a speculative facet to architecture, Pasing’s renderings certainly belong to this genre (as does Taut and Scheerbart’s Alp-blanketing Glass Architecture), although he consciously avoids the brave-new-world utopianism usually associated with the visionary. But neither are they dystopian or apocalyptic, simply a celebration of a bio-machine aesthetic. His machines seem to be charged with a capacity for time travel, to visit the ancient Roman Forum or what looks like Pliny’s country Villa. Here painted contexts pirated from Art History give the images a borrowed authenticity, although one wonders what the Inquisition would have said if the giant guts of a robot, with drone-like propellors, had appeared above a Canaletto festival (perhaps the Venice waterfront would have been less crowded).

Outside of Time is the category Pasing invokes for these counter-factual histories. One of the most evocative is an invasion of a traditional Dutch landscape painting, an 1899 Windmill on Polder by Paul Joseph Constantin Gabriel—romantic in the extreme—a windmill firmly anchored in polder mud, the land is slowly and patiently being made (Aeolian pumping), a glimpse of the archaic alchemy of land emerging from primal-slime, which the historian Simon Sharma tells us is a foundational mythology of the Netherlands (The Embarrassment of Riches). The entire picture, both sky and water are a septic-primeval chemical yellow, except for the warm comforting and haptic reddish tone of the windmill box and adjacent thatch roof. What can a Pasing techno-mirage on the horizon add to this already loaded and almost mawkish bucolic atmosphere? Rustic windmill technology is mirrored by the implied futuristic mechanics of the newcomer, it is saying ‘I too can play your game of pitching artifice against the scale of the wide polder horizon, against the forces of nature’. Here as in many of Pasing’s machines a dramatic horizontal cantilever defies gravity and mirrors the earth’s surface. To the right a swathe of umbilical cables connects the newcomer to a hovering mothership. Is this a new technology extracting energy from the mudflats to keep the mothership aloft? Or is the mothership, circled by adulatory birds, a godhead about to ascend into the golden heavens? Elsewhere in the book Pasing invokes ‘A Machine called—only my yearning shows how much I suffer’, a Goethe quote attributing Freudian symptoms to these invasive machine mirages—constituting an empire of tech-things.

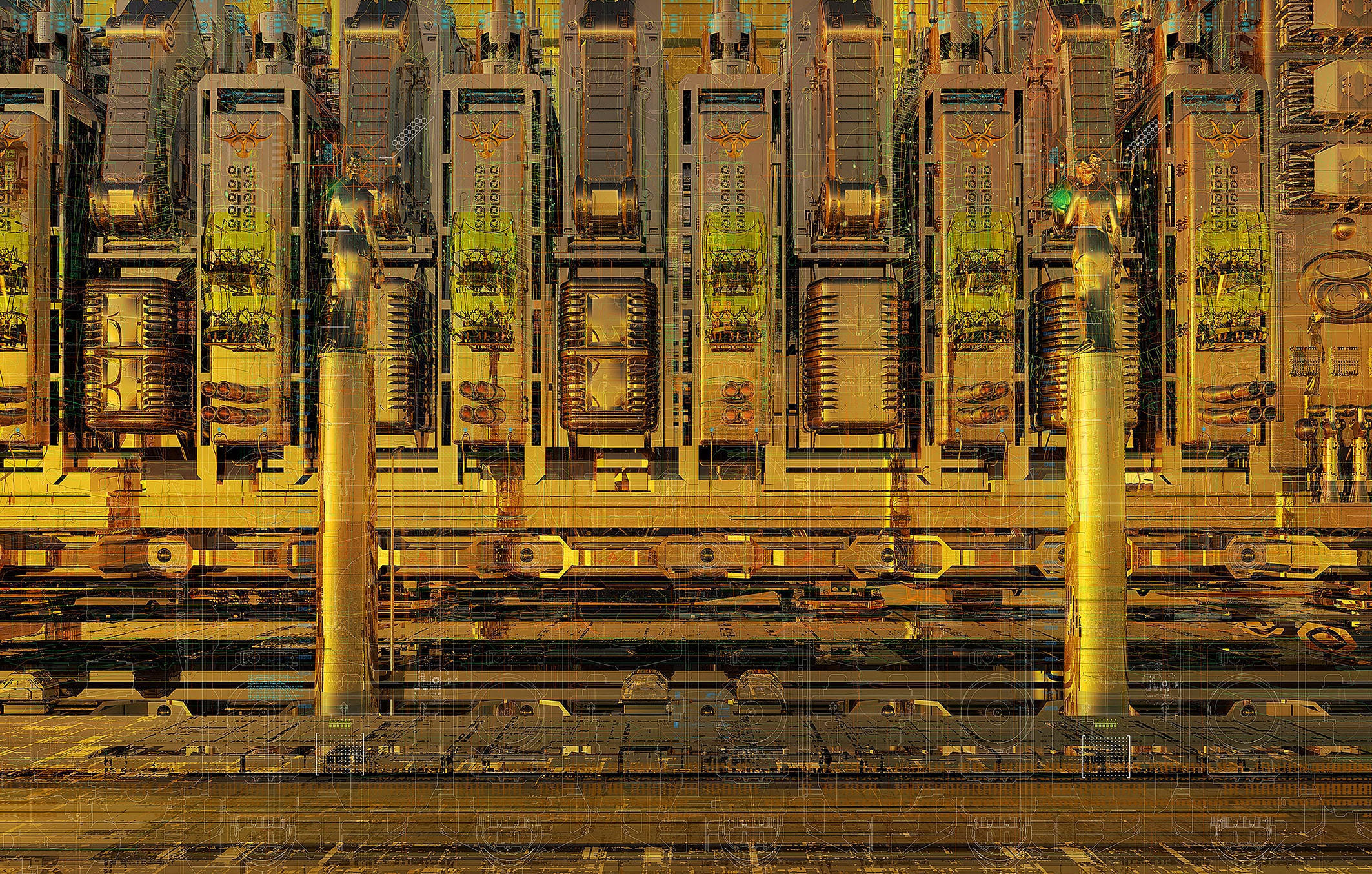

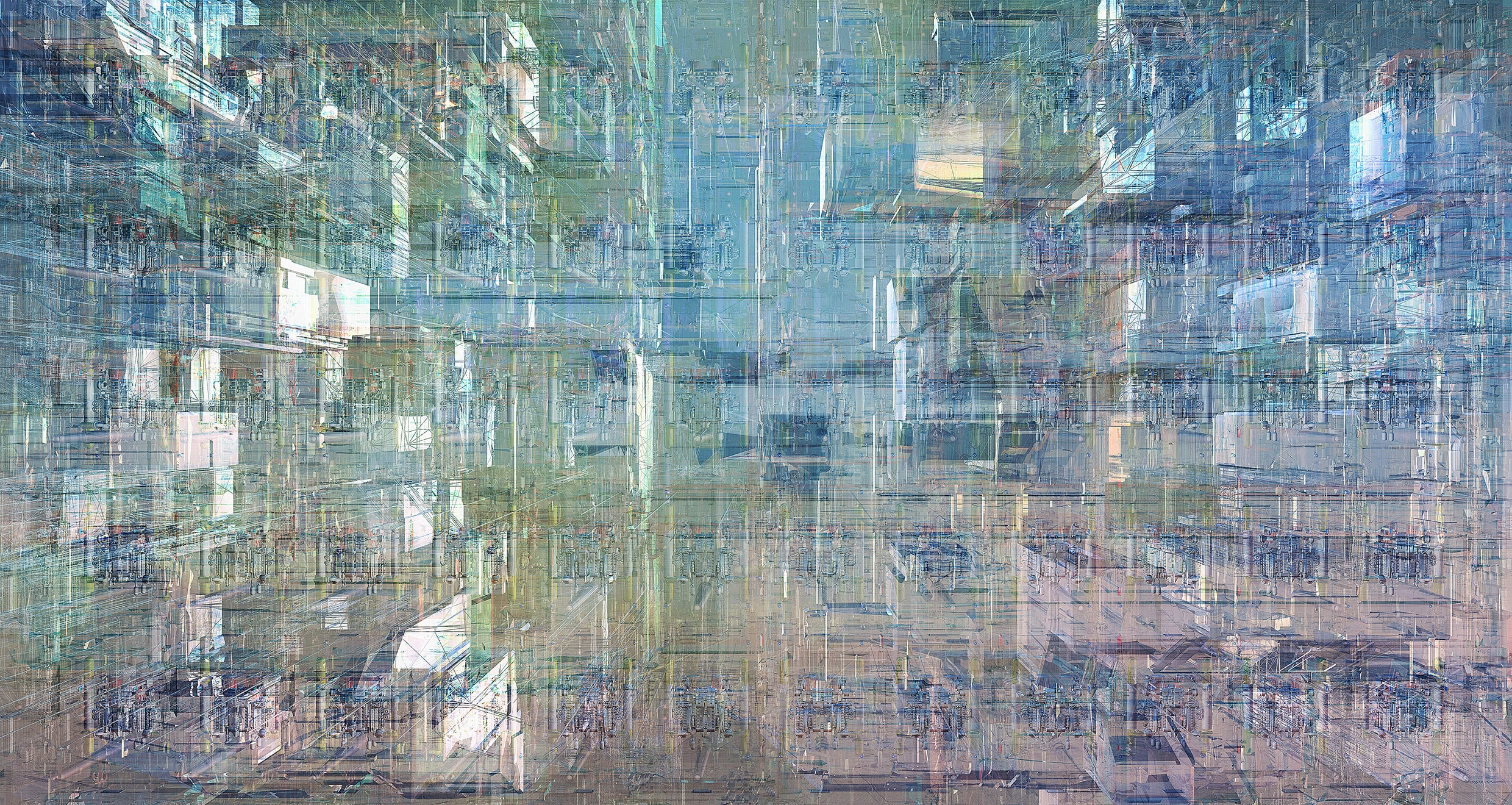

But not immortal tech-things—The Last Journey—a shining golden series of images in Part Aconjures a glittering funeral device projecting people or their robotic virtual avatars to eternity. And even this virtual eternity is conjured in the chapter called The Big House of Ice—the last farewell. Here Pasing is at his most accomplished in rendering an ethereal spatial construct of astounding tectonic complexity, washed by a ‘Slightly Bluish Cold Light’. As always, the images eclipse the accompanying narrative except for the Polar Bears hovering outside the Big house of Ice, as if they had inflicted an ecological disaster on the humans trapped within. Or am I confusing this slightly bluish light with Theatre 0—Wellness Resort for AI—fragile traceries hovering in an upper atmosphere azure—the pinkish blue one sees from an airplane window at dawn, a white noise zone Pasing’s AI calls it. Maybe even AIs with their massive demand on global resources (water and energy) should be granted or at least dispatched to their own Nirvana.

My respect for Anton Markus Pasing is that of a dinosaur for a hairy mammoth (of the digital ice age). We both live in provincial Münster, beyond the event horizon of contemporary discourse. A ruse that allows both to pursue our individual obsessive trajectories, in my case the building of buildings across Europe and a refusal to stop drawing (illustration)—in his, a Professorship in Düsseldorf and rushing back to his villa to knuckle down to digital meditation. It is important to know that he shares this villa with his wife and a museum scale collection of tin-toy robots. He is a Peter Pan of the Star Wars generation. His works also exude a kinship with Hollywood films. I have heard that his digital skills are so advanced that he teaches classes of film animators. He regularly wins prizes for architectural representations but over the last ten years has moved into the fine art category. As a consequence, works produced under this rubric were shown by a reputable Cologne gallery in 2022-2023.

This sidestepping of an architectural obligation in his imagery has engendered a new evolution in formatting. Large scale fields of digital registers are each a triumph of an entirely self-sufficient nomination which Pasing refers to as Deep Surfaces. With titles like Translocation, Veritable Disassembly, Affliction (Heimsuchung) they are like digital Jackson Pollocks—all surface—of equal distribution, no foreground, no background, no figure-ground. They bring into focus the omnipotence, the slothful serenity of the self-authenticating digital prototype. I believe they are printed on metal, giving the virtual a material foundation. In these digital images we find a contemporary update of Marshal McLuhan’s The Media is the Massage (1967). Turbine Room from 2022-2023 belongs to this series, an ice-cold bluish haze that nostalgically invokes a Hollywood film (Matrix). Also quoted on the pages of Unindebted Assumptions is the epic Tannhauser Gate line from Bladerunner. Almost as if describing a Pasing-scape, the last words of the Titanic replicant played by Rutger Hauer were: ‘I’ve seen things you people wouldn’t believe. Attack ships off the shoulder of Orion. I watched C-beams glitter in the dark near the Tannhauser Gate. All these things will be lost like tears in the rain. Time to die.’

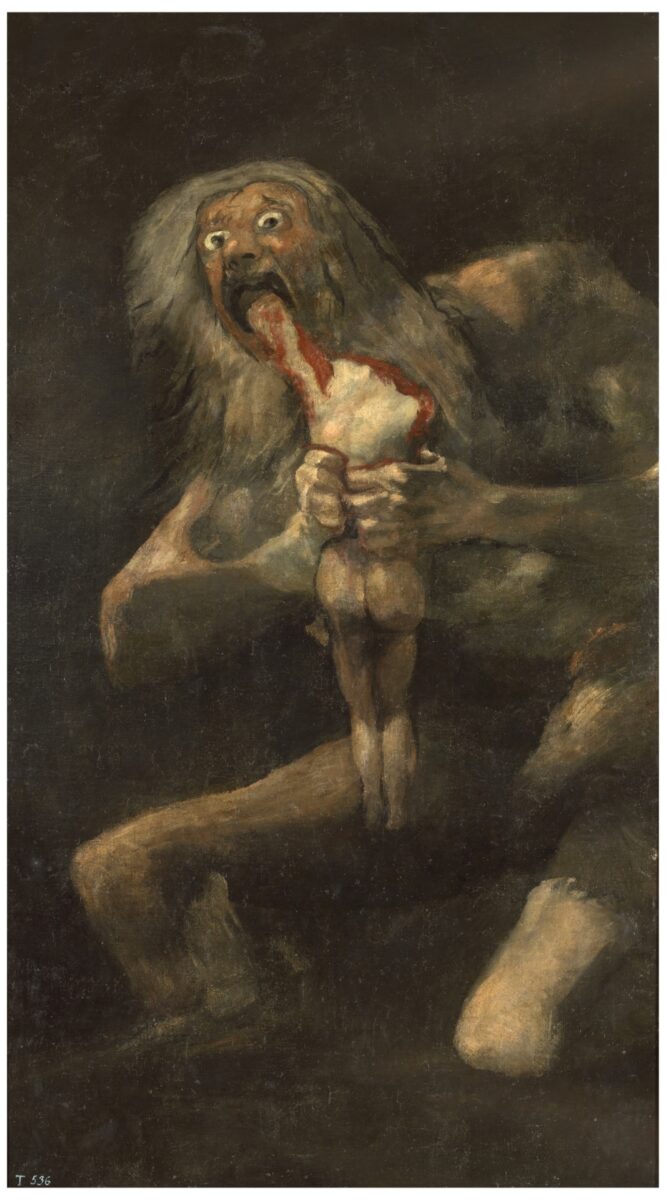

Yet another facet in the work of Pasing drifts to the dark side. A 2016 series called Quiet Rooms projects gloomy stages in gridded perspective, oppressive in the extreme, Kafkaesque in their sombre logic of verisimilitude. The reintroduction of weighty rectangular panels in these spaces embodies an indictment of the tectonic logic of architecture (in comparison to airy virtual clouds). Such settings could dispatch people to purgatory, they are luckily rendered unoccupied except for a couple of skulking rats. One is reminded of Adolph Appia’s sets for Wagner (the foreboding dungeon of Klingsor) also of Goya’s Black Pictures in the Prato called The Sleep of Reason (El Sueño de la Razon Produce Monstrous—The Sleep of Reason Produces Monsters).

Shortly after these neurotically dark 2016 renderings Pasing produced another series of images titled Beyond Darkness,equally as black, butthe all-encompassing architecture has solidified into autonomous hovering objects sculpted in what could be read as dark matter. Here an implied scientific analogy runs into a very up-to-date problem. A recently published Post Quantum Theory speculates that time may flow randomly and fluidly making space haphazardly warped. This implies that zones may exist that do not observe the laws of classical or quantum theory—a wobbly space-time with no need of dark matter to explain it.

Regarding explanations, it is unnecessary to comb the collected works of Pasing looking for authorial justifications. If there were any, they should be regarded with the same skepticism a psycho-analyst reserves for his patient’s explanation of his own symptoms.

Like the deaf painter Goya (who ultimately abandoned the grotesque and dark world of a pre-Enlightenment Spanish court) Anton Markus Pasing escapes regularly to the empty expanses of the North German Island of Norderney. If his projected images can be designated Digital Elswheres, he has here found a physical elsewhere of matching poetic resonance. I use the term ‘elsewhere’ as in cosmology—a location beyond the event horizon of a singularity—i.e. beyond the quotidian details of our everyday lives. These Norderney tidal flats, where the coasts of Germany and the Netherlands dissolve into the North Sea, are introduced as northern territories (not to be confused with the Australian Northern Territories where the mysterious Uluru Rock is located). The bleached ambience of these expanses are rendered in an engulfing yellow haze, not dissimilar to reportage of the Gulf War. There it was the debris of conflict that hovered in the sandstorm, in the northern territories it is a by now familiar taxonomy of Pasing’s intimidating techno characters. In later iterations they melt or dissolve into haunting silhouettes, eroding residues of a fetishistic figuration. Is a catharsis here underway? Landscape itself triggering a purging of the techno-neurosis. Here digitally constructed images at one point merge with photos of tidal eddies and ‘leaves of grass‘ (Walt Whitman’s metaphor). Pasing enigmatically describes these hyper realistic dune-grass fields as the result of his own invented AI.

This derive through the oeuvre of Anton Markus Pasing began with the ‘Neurotic I am’ quote from Roland Barthes’ The Pleasure of the Text (1975). We can in conclusion suggest reading Pasing’s haunting images as visual texts where, as Barthes says ‘a bit of neurosis is necessary for the seduction of the reader-viewer’. This immense lexicon is challenging, it cannot be accessed via the conformist discourse (non-discourse) of the internet scanner. The pleasure it takes in the seductive image invokes a certain guilt, it may well be either idle or vain. Representation is an embarrassed figuration encumbered with other grand narratives like: reality, morality, likelihood or truth. In the oeuvre of Pasing we are not dealing with representation but with figuration, diagrammatic and not imitative, a body split into fetish objects and erotic sites.

As Barthes concludes ‘the monument of psychoanalysis must be traversed—like the fine thoroughfares of a vast city, across which we can play, dream etc.: a fiction’.

Peter Wilson is a founding partner in Architekturebüro BOLLES+WILSON. Peter is the author of Some Reasons for Traveling to Italy (2016), Some Reasons for Traveling to Albania (2019) and Bedtime Stories for Architects (2023). His drawings are held in the collections of Drawing Matter, V+A, CCA, DAM Frankfurt. BOLLES+WILSON are the subject of three El Croquis Monographs and the publication, A Handful of Productive Paradigms (2009).

Anton Markus Pasing’s studio ‘remote-controlled’, founded in 1994, works in the field of ‘space-encompassing artistic research’. Since 2005, he has been a professor of architecture and typology at the Peter Behrens School of Arts in Düsseldorf, where he conducts research into analogue and digital, spatial and structural design processes. One of his current studio works, ‘The Wall’, was exhibited at ‘Sir John Soane’s Musuem’ in London in 2023.

– Mark Dorrian