Architecture’s Mirror Stage

Mirrors and mirrored glass, perhaps the most characteristically postmodern of surface treatments, were not only a material choice but also emblematized a turn inward toward what Sylvia Lavin has taken to calling ‘architecture itself.’ As the psychoanalyst Jacques Lacan might have put it, it was at this moment that modernist architecture became aware of itself as an object of desire, and reified this awareness into anxiety and aphasia. Architecture was looking at itself, and it didn’t always like what it saw.

During this ‘mirror phase,’ reflective surfaces were used to create a variety of visual effects. When used as cladding to the exterior of skyscrapers —their most familiar application — they often effaced a building’s shape and size through reflection of the sky or its surroundings. When applied inside buildings, they created dazzling, spectral, and sometimes kaleidoscopic atmospheres. These effects were ever-changing, hard to predict, and even harder to draw.

One practice that tried was the Detroit-based firm of Gunnar Birkerts and Associates (GBA), led by the Latvian-American late modernist, who went on to design the monumental national library in Riga, his birthplace. GBA’s building designs of the 1970s made ample use of mirror effects for various purposes. In their underground addition to the University of Michigan’s Law Library, for example, mirrors clad structural members to efface their presence and visually lighten their heft. In other applications, they served a more functional purpose, as in the IBM Regional Office Building the firm designed in suburban Southfield, Michigan, where concave surfaces diffused and distributed even light over the interior while maximizing the building’s insulation and thereby its environmental performance.

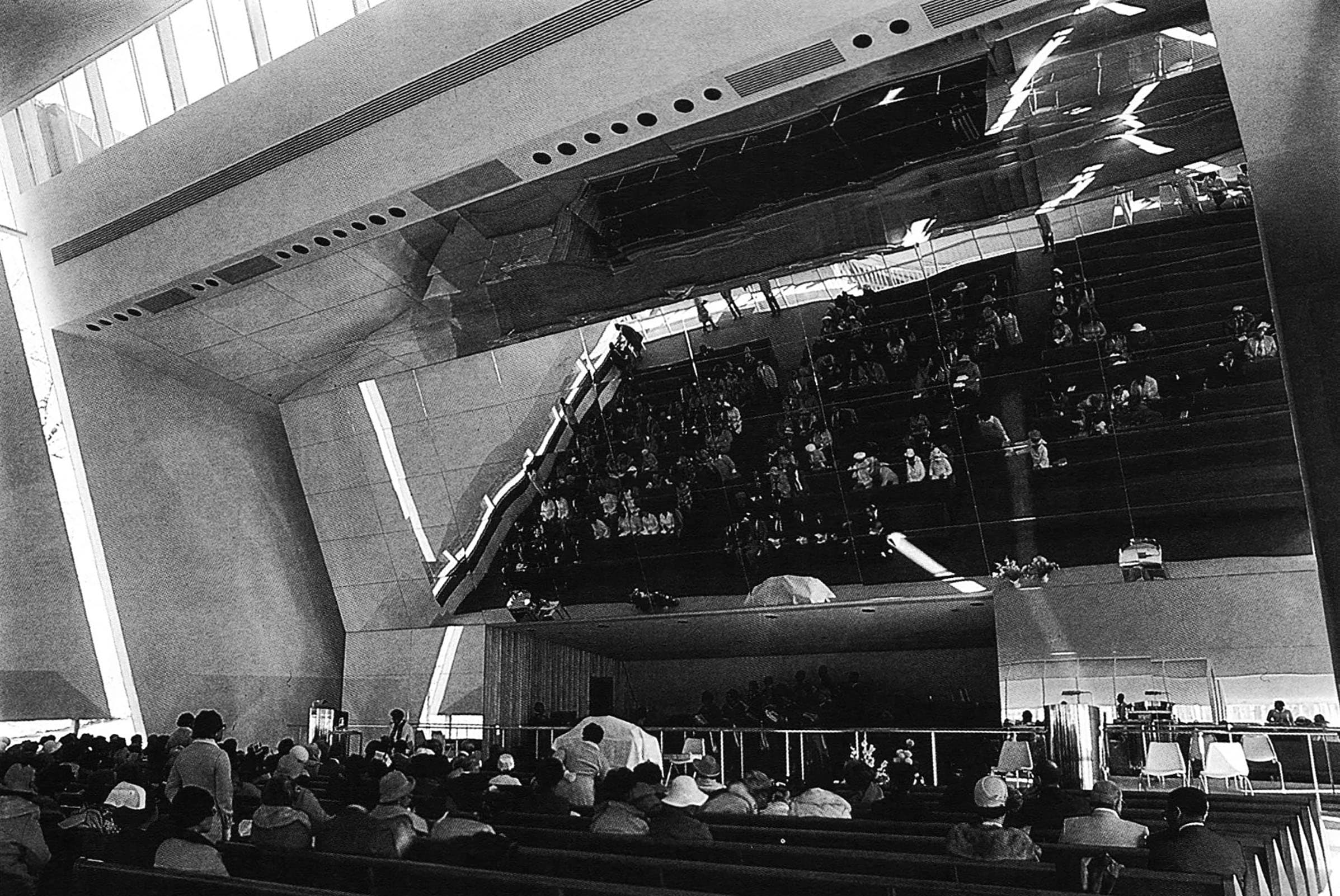

Mirrors were also specified not only for what they reflected, but also what they could draw into being, namely, new forms of subjectivity, both individual and collective. The most dramatic example of this in GBA’s work is at Calvary Baptist Church in Detroit, where, upon entering the worship space one is confronted with a massive panelised wall of mirrors reaching forward overtop the pews like a petrified wave. The largest and most perplexing of the church’s several mirrored surfaces is the central facet of this wall. Oriented at 25 degrees from the vertical, it returns congregants a picture of themselves as part of the congregation. It is intended to make the group reflect on their membership in a faith community and participation in the work of worship.

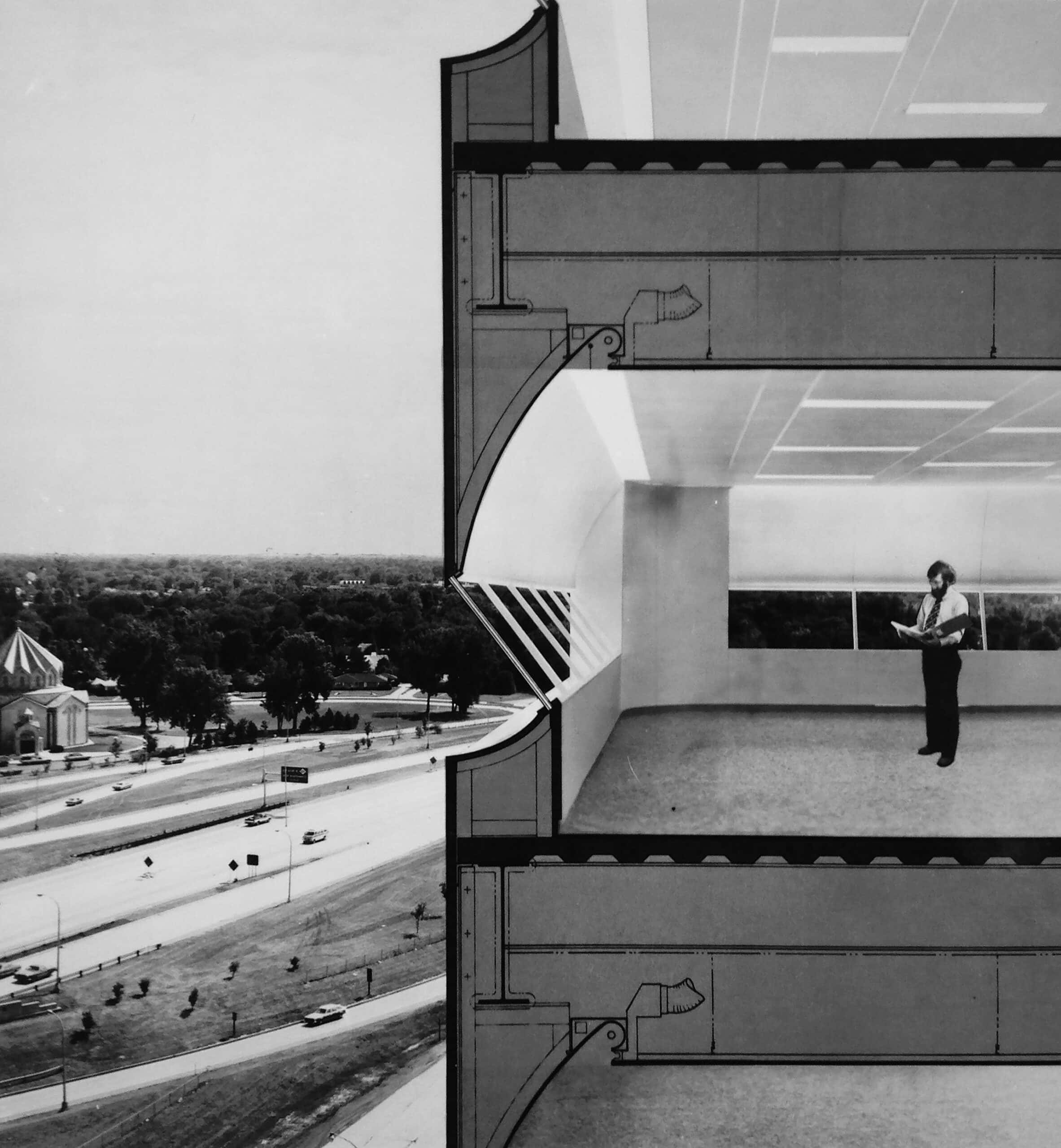

These varying applications induced an equal variety of representational modes. Many were conceived primarily in section drawings, through which reflections could be calibrated acutely and accurately. But others, like IBM Southfield, required hybridized section-perspectives to convey the designers’ intentions. In one of these [below], a solitary bearded man stands in an empty office space gazing at a binder. The drawing illustrates that the even diffuse light that pervades the space is achieved not by fluorescent bulbs (though they are present in the drop ceiling) but with the system of reflecting lenses built into the building’s exterior walls. Moreover, because of their orientation and framing, the downcast transparent panes appear less like picture windows than like museum vitrines. Through these openings, occupants could inspect the suburban specimens that surround them in the very same posture as the scale figure inspecting his documents.

GBA’s ostensible achievement was to drastically improve the environmental performance of this office building at the height of the oil crisis. Yet this disguised a continuation of Birkerts’ career-long experimentation with the ways that walls could be, as he once put it, ‘formed to receive glass’ rather than merely punctured with a window. This line of thinking ultimately bore its strangest fruit in a commission that, appropriately enough, came from a museum dedicated to glass.

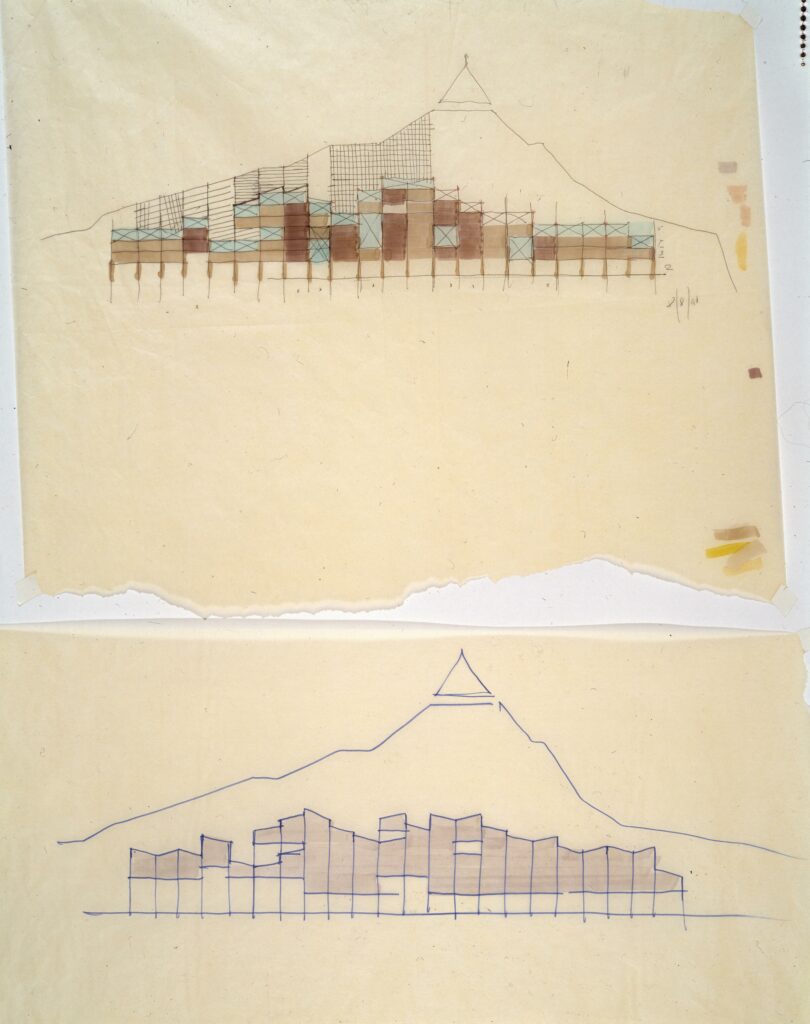

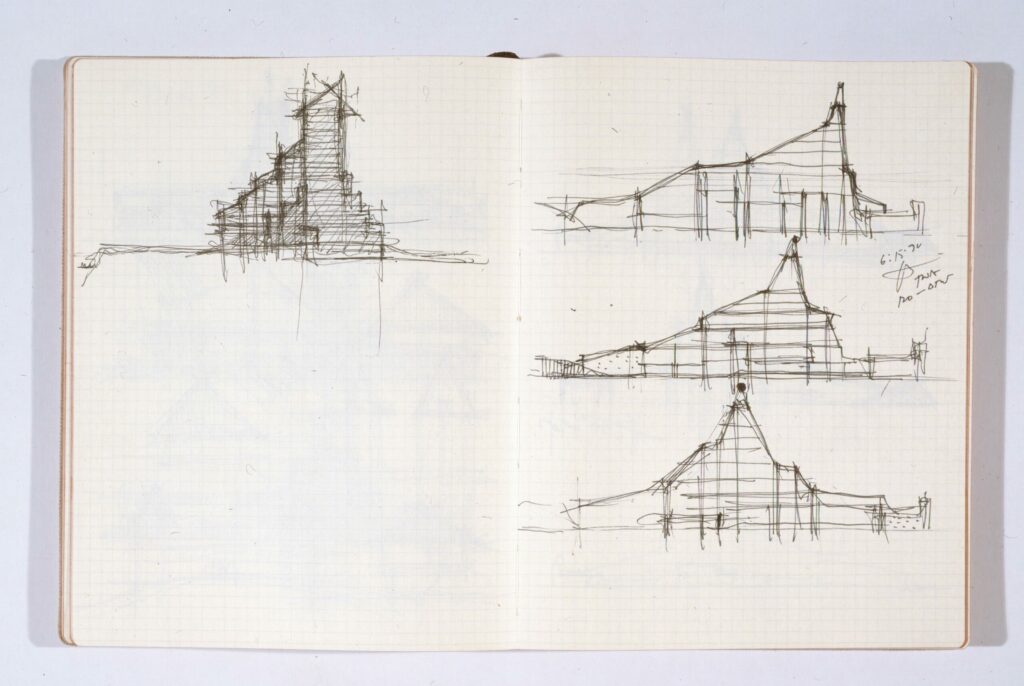

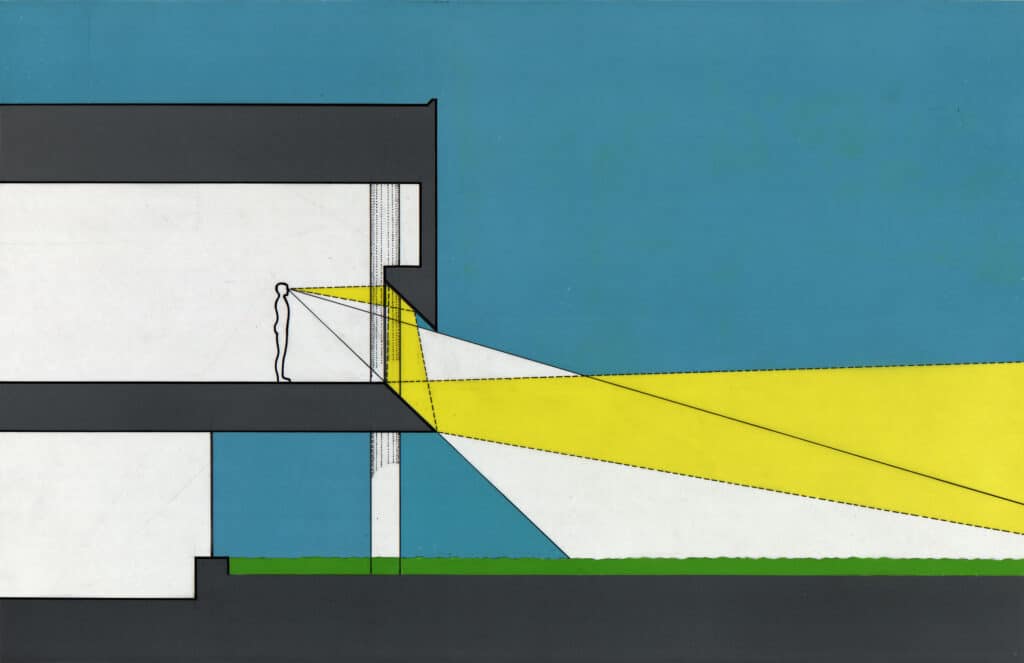

The Corning Museum of Glass in Corning, New York sits on the edge of what in the late 1970s was an active corporate headquarters complex for its namesake, the industrial Corning Glass Works alongside its subsidiary, the artisanal Steuben Glass Works. As client, the museum encouraged GBA to explore new effects and applications for Corning’s signature material. A section drawing overlaid with brightly coloured film illustrates one outcome of their lengthy design process — mirrors in a periscope arrangement that reframe or mediate one’s view of the outside world. This building is, one might say, a device for defamiliarization.

The building’s complexity in plan only heightens its effect. Arrayed in semi and quarter circles in a form that was meant to mimic the crystalline shapes formed by rapidly cooling glass, the periscopic mirrors in fact act more like kaleidoscopes, fragmenting and fracturing the landscape itself into patterns of light and colour. The feeling is akin to being within a mirror rather than looking into it.

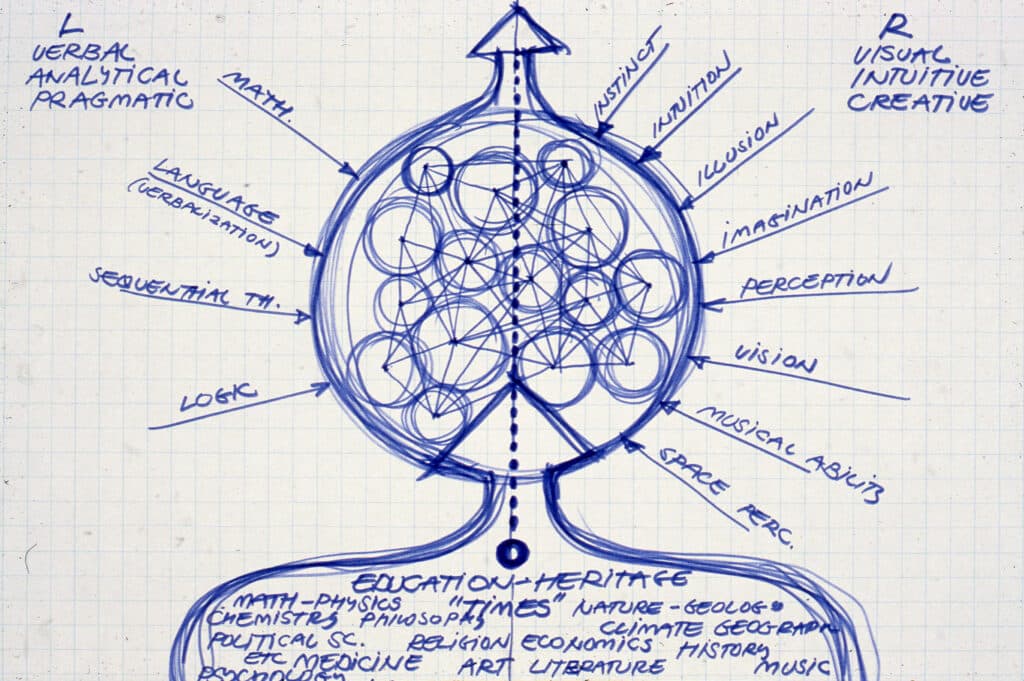

In the drawing, [above] an unclad, featureless scale figure casts two overlaid gazes simultaneously. One is directed into the periscopic wall, reflected downward and outward toward the horizon and the Chemung River floodplain on which the building sits. The other is downcast, facing through the periscope onto the museum’s manicured lawn. These illustrate the estrangement of nature, of the horizon, and of visitors themselves at work in the building design. The drawing is perhaps a reflection on individualization and identity — the way one’s self-image is always informed by a cobbling together of history and autobiography, as depicted in a later Birkerts lecture slide showing the elements of his own education and heritage [below]. This psychologized architecture confronts the visitor with their own fragmented lifeworld.

The figure depicted in GBA’s drawing is, therefore, hardly the unified subject of Enlightenment modernity, and, in its solitude, neither does it engage in the intersubjective, empathic engagement of Phenomenology. One might, in fact, see the design as a critique of phenomenological perspectives on architecture that were gaining influence at the moment the drawing was produced. This and other of GBA’s designs emphasize our inevitable, anxious distance from the supposedly authentic experiences that might trigger ontological questioning. These drawings reveal that ‘architecture itself’ is always both a mediated experience and an experience of mediation.

Michael Abrahamson is a faculty member at the University of Utah School of Architecture, where his research and teaching explore the materiality of buildings and methods of architectural practice across the twentieth century.

This text was submitted in the long form category (1000–1500 words) of the Drawing Matter Writing Prize 2020.