Behind the Lines 10

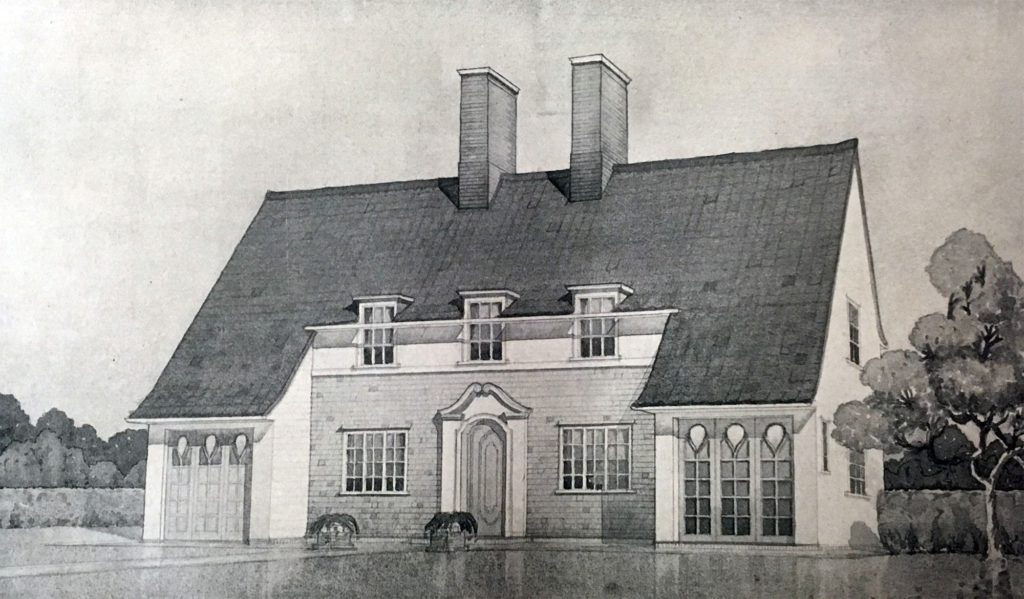

It was undoubtedly the doing of that ancient buffer Lutyens, Samuel Hardy reflected sourly, as he stared at the pages of the September 1932 issue of The Builder and saw an illustration of the winning entry. It showed Mr Edward H Banks of ‘Villa Desiré’, Downlands Road, Purley, Surrey’s awful concoction of a house with its ragbag of features: feeble swan neck pediment, ridiculous tall chimneys, Glasgow School patterning on the garage doors and loggia glazing, plus hideous half dormers bisected with guttering. What type of pretentious fellow calls his house Villa Desiré anyway, he thought grumpily.

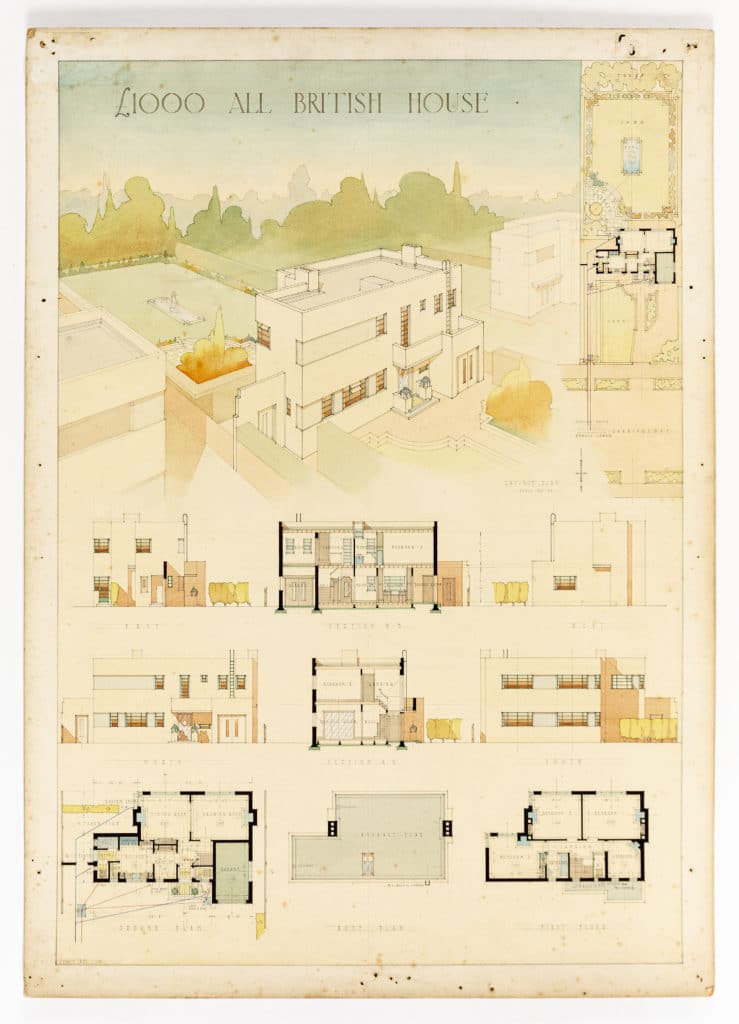

He wasn’t sure about the IAAS – why did they need to break away from the RIBA? He had recently read a report of Lutyens’ presidential speech to the IAAS and gloomily noted the old man’s statement: ‘I crave for soft thick noiseless walls of hand-made brick and lime, the deep light reflecting reveals, double doors, easy stairways and doorways never less that 1ft 6in away from a corner.’ He – Hardy – should have thought this project through. Lutyens was never, in a million years, going to approve a flat roof. It was a red rag to an old bull. With hindsight why had he wasted so many hours working on his 30 x 22in Whatman board (scale 8ft to 1in), working out how to fit in all four elevations, two sections, two floor plans, site plan and a bird’s eye perspective of house and garden all the while dreading a smudge of ink or spillage of tea as he worked.

No one enters a competition without imagining that they will win it. Young Samuel Hardy of Bournemouth, freshly qualified, had, as a matter of course, imagined that his entry would amaze and delight the judges. The list of assessors had seemed uncontentious – obviously Lutyens as President was one; there were four practising architects – fair enough; the President of the Institute of Builders – perfectly reasonable – and lastly, the frivolous, and as he thought entirely peculiar, inclusion of Miss Winifred Johnson, editor of My Home and Woman and Home. He had supposed that she would have little to contribute and even less influence.

The brief had been to design a house costing £1000, excepting the cost of the site and architect’s fees. The competition’s declared purpose was to encourage the use of ‘All British Building Materials’ and to demonstrate the advantage of commissioning an architect. Thinking of his recent visit to see the Crittal factory village at Silver End, Hardy had immediately decided that their metal windows would be an essential element in his design – what, after all, could be more British than Braintree? The slim horizontal lines of the glazing bars, painted jade green, would look fine against the smooth white rendered walls. Parthenon, the IAAS journal, was full of advertisements from the Associated Portland Cement Manufacturers for ready mixed products such as ‘Snowcrete’ (in three standard tones) ‘for stucco finishes, rendering and pointing’. How could anything named Portland came from anywhere but England? He had never given the flat roof a second thought, it was so obviously the modern solution.

This was, after all, 1932. He had even daydreamed of conversations with the wife of the £1000 client about access for sunbathing. Bournemouth had no shortage of folk wealthy enough to build a house like his. There were plots on Sandbanks still available he knew.

When Samuel Hardy turned over the page and looked at what was oddly termed the ‘Third Premiated Design’ he groaned. The only feature that demonstrated it wasn’t still 1911 was the addition of a garage stuck on the side of the house. Ridiculously small windows, excessively steep gable roof and patterned brickwork reminiscent of a Victorian terrace in Swindon. Maybe that was what ‘All British’ meant to the IAAS judges. Not to him, had none of these men looked at anything being built further than Dover?

Samuel Hardy had to wait for the October issue of Parthenon to come out to read a detailed account of the competition, which he did in a very bad mood: ‘No fewer than 369 entries had been received from all over the Empire…drastic changes had taken place in small domestic architecture within the last few years. The layout of the drawings reflected thought, artistic temperament and training.’ Exactly so, Hardy thought to himself, and braced himself to read the critique of Mr. ’Villa Desiré’ Banks’s winning house: ‘detail of refined character…north elevation simple and dignified…the lounge is a nice room and the dining room adequate…kitchen is conveniently arranged, but a little more width would have been an advantage.’ Ah, a contribution from Miss Winifred Johnson no doubt. Damn, and here she was sticking her oar in again: the second prize house made ‘full use of modern labour-saving devices in the kitchen.’ He had underestimated her importance.

Of the third prize house, which he so particularly despised, he read that it had: ‘Nothing that is new but at the same time no feature fails to harmonise and the result as a whole is extremely pleasing’. With increasing horror he read that ‘in the drawing room an ingle is introduced, and although it may be an ornamental feature it is questionable whether, as designed it would be particularly comfortable or useful.’ Too right – crouching in a dark round some smoky, cosy-corner inglenook made him think with a shudder of his parents’ dark, beamed house with its Jacobean pattern chintzes and Tudoresque furniture. Did the judges have no idea of the beauty and the healthiness of rooms filled with sunlight and air, such as he had presented? Evidently not.

The domestic interests of Miss Johnson, for whom he was developing a serious antipathy, seemed to occupy most of the competition summing up. Who cared that ‘considerable use was made of kitchen cabinets, cold storage cupboards and combined hatches and china stores’ –this was an architecture competition, not the Ideal Home Exhibition. He read on: ‘The kitchens were invariably small. In one instance a sitting and meals recess was provided for the maid as part of the kitchen, whilst in another a small maid’s room was inserted between the kitchen and the hall.’

With a jolt of recognition, he realised this was a reference to his own plan. He had always felt sorry for Doris, his parents’ maid, sitting in the kitchen on a hard chair at the kitchen table for hours on end, so he had planned a small sitting room for the maid. It was unclear whether this was admired or not. In any case it certainly wasn’t what he wanted to be mentioned for. After another paragraph about some entrants cleverly contriving covered entrances to garages the report stopped abruptly. Samuel Hardy felt let down.

It so happened that a month later Hardy was to read, and note with a degree of schadenfreude, the following letter from Ernest G Allen FRIBA in the October issue of the Builder: ‘no reasonable person will take exception to the elevation of the winning design…but surely construction should have some bearing on the award, and it would be interesting to know how the author of the design proposes to construct the chimney.’

A few weeks later that same month he came across a snippet in the paper that the distinguished architect, Sir Edwin Lutyens and his wife were undertaking a lengthy continental tour to Pompeii, Athens, Constantinople, Damascus, Cyprus, Baalbec, Jerusalem and Cairo and had left England in August. Samuel Hardy realised that Lutyens wouldn’t have even seen his drawing…did that make it better or worse?

– Philippa Lewis