Cedric Price: Parc de la Villette

The following account looks into the drawing DMC 1438 related to Price’s Parc de la Villette competition entry, to quest for the modes in which this media object resituates his design approach of design for pleasure, not only as the evolution of his practice, but crucially as part of an enduring conversation with Joan Littlewood that had been initiated in the 1960s with the Fun Palace project.

In a dimly lit room, Cedric Price shifts gently his cards, sips the red wine left in his glass and begins to unpack what designing for pleasure and delight—a core principle of his architectural practice—entails: ‘it was just off Times Square, with a Yorksman who’d become a theatrical agent … Joan Littlewood and myself, at a little drunken early morning brain stretching session (audience laughs) on what’s called this brilliant thing that we were designing in London.’ Rejoicing the remembrance of the moment, he lights a cigar and goes on: ‘we went through layers of sort of verbal nausea … until we arrived at Fun Palace—we thought it really tummy-turning.’Yet fun, Price adds with irony, ‘is now something that architects specialise in (audience laughs).'[1]

Price recounts the anecdote of how the name Fun Palace came about during the five-part and two-day lecture Autumn Always Gets Me Badly, held at the Architectural Association, London, in November 1989, in order to challenge the complicity of concurrent architecture within the commodification of fun. For ‘fun buildings’ crucially lack the active force of pleasure brought about by the choice made available to the user. Instead, Price argues that pleasure and delight should become an integral provision in any design undertaken irrespective of its program. Delight is pursued through designs that create opportunities for self-directed time, choice, change, doubt, wonder and surprise, all intended for the user’s enjoyment—even if it is hard work for the designer, Price warns. And so, he concludes with a proposition: ‘not to imagine the end-product when planning for pleasure, but rather (try) very hard to introduce in whatever (one) is doing a mental frontiersman element for a split second in the user.’[2]

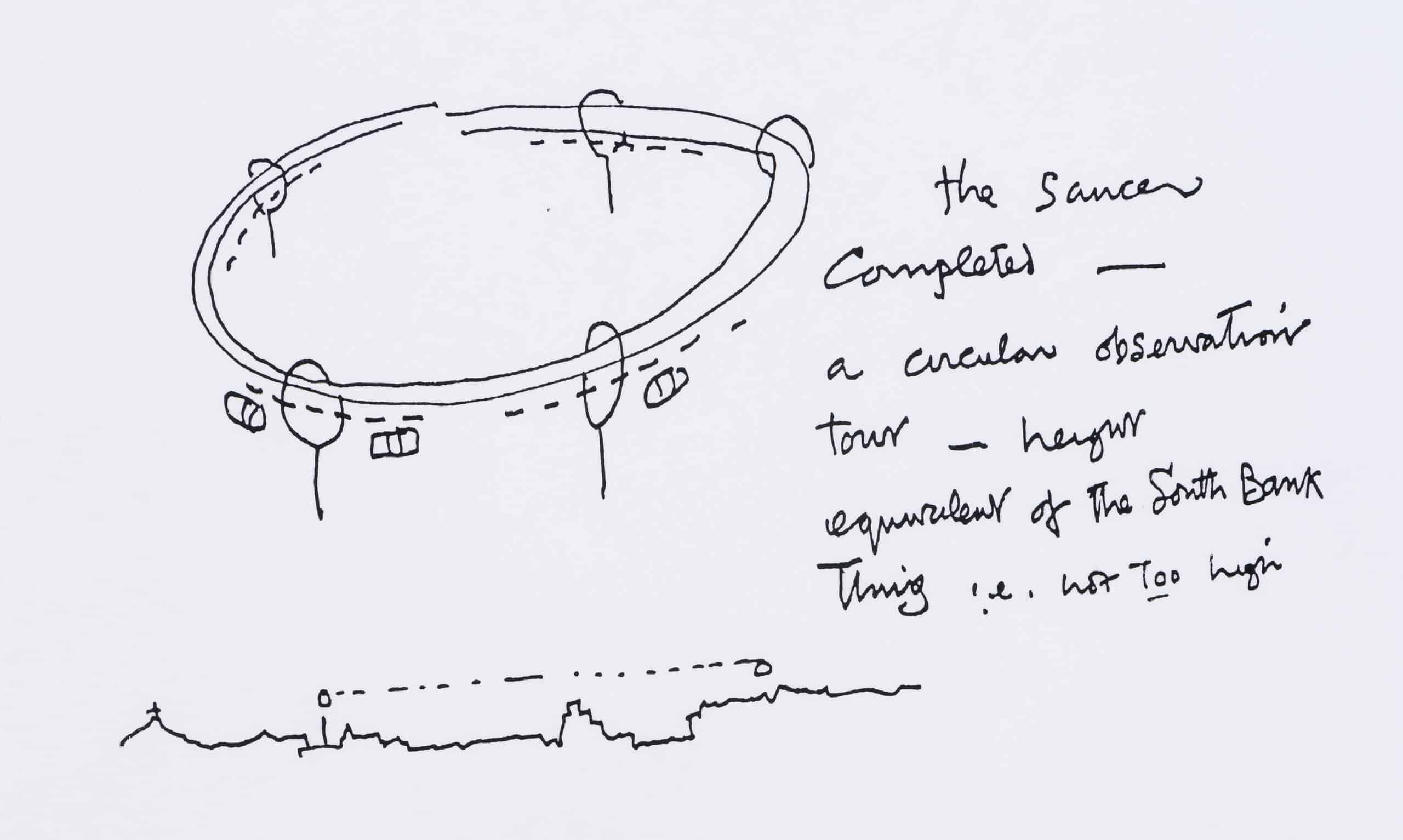

The section ‘Uncertainty and Delight in the Unknown’ in Cedric Price: Works II, published with the occasion of the exhibition of his work at the Architectural Association in 1984 and reprinted as The Square Book, offers a constellation of modes to achieve this: the deep framework of the major Fun Palace servicing changeable suspended enclosures for self-paced engagement; the lightweight and ground-based modules operated by a mobile crane of the Camden Pilot project; the range of uncommitted areas opened within the existing urban fabric in South Bank—‘London’s last communal lung’—which are then occupied by a troupe of contrivances to activate further the site, some named such as ‘The Thing’, yet mainly anonymous. ‘Such a fora for change’—claims Price—‘are central to the meaning of City.'[3]

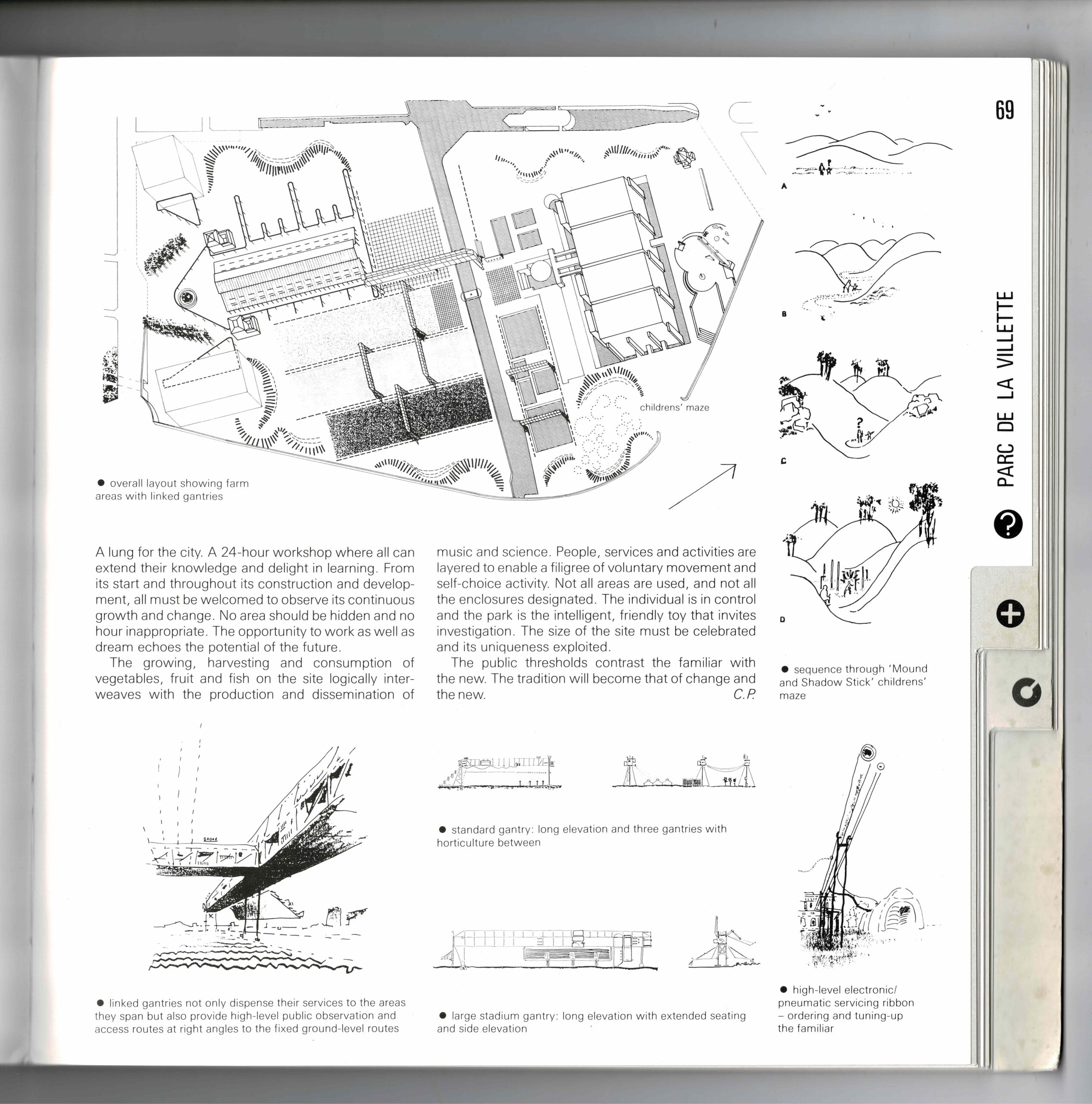

The competition entry for Parc de la Villette was among these projects. ‘A lung for the city’ —opens the text describing the project:

‘A 24-hour workshop where all can extend their knowledge and delight in learning. From its start and throughout its construction and development, all must be welcomed to observe its continuous growth and change. No area should be hidden and no hour inappropriate. The opportunity to work as well as dream echoes the potential of the future. The growing, harvesting and consumption of vegetables, fruit and fish on the site logically interweaves with the production and dissemination of music and science. People, service and activities are layered to enable a filigree of voluntary movement and self–choice activity. Not all areas are used, and not all the enclosure designated. The individual is in control and the park is the intelligent, friendly toy that invites investigation. The size of the site must be celebrated, and its uniqueness exploited. The public thresholds contrast the familiar with the new. The tradition will become that of change and the new.’[4]

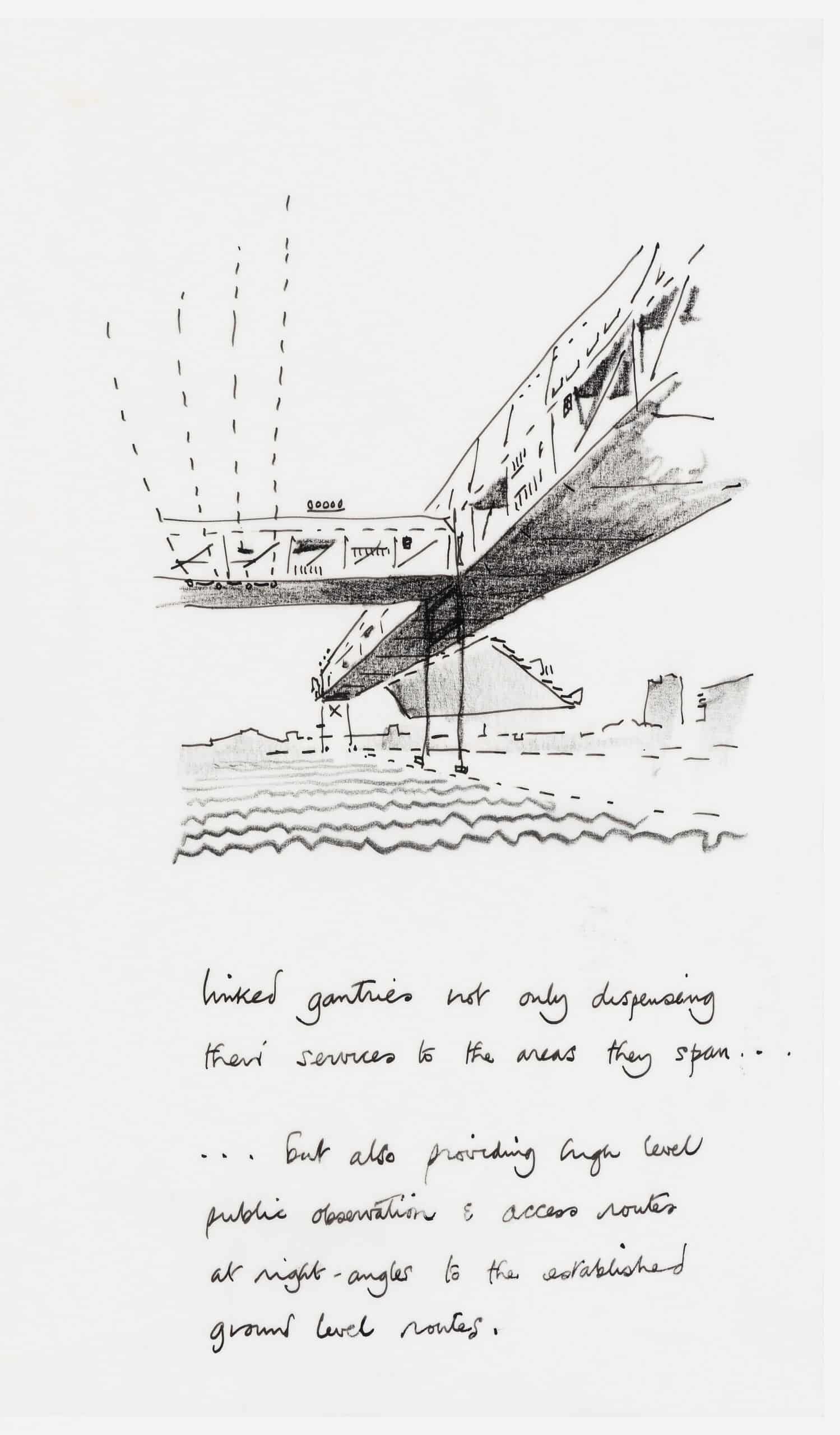

Price envisioned a metropolitan food resource and leisure centre served by high-level infrastructure. Reservoirs of uncommitted land were built in the design to accommodate change and a taxonomy of gantries facilitated public observation and self-paced movement: the kind that bridges horticulture patches, the ‘large stadium gantry… with extended seating’, the linked sections providing access and further ‘high-level public observation’, and the high-level electronic and pneumatic servicing ribbon ‘ordering and tuning up the familiar’[5]. All these architectures would enable the delights of the park.

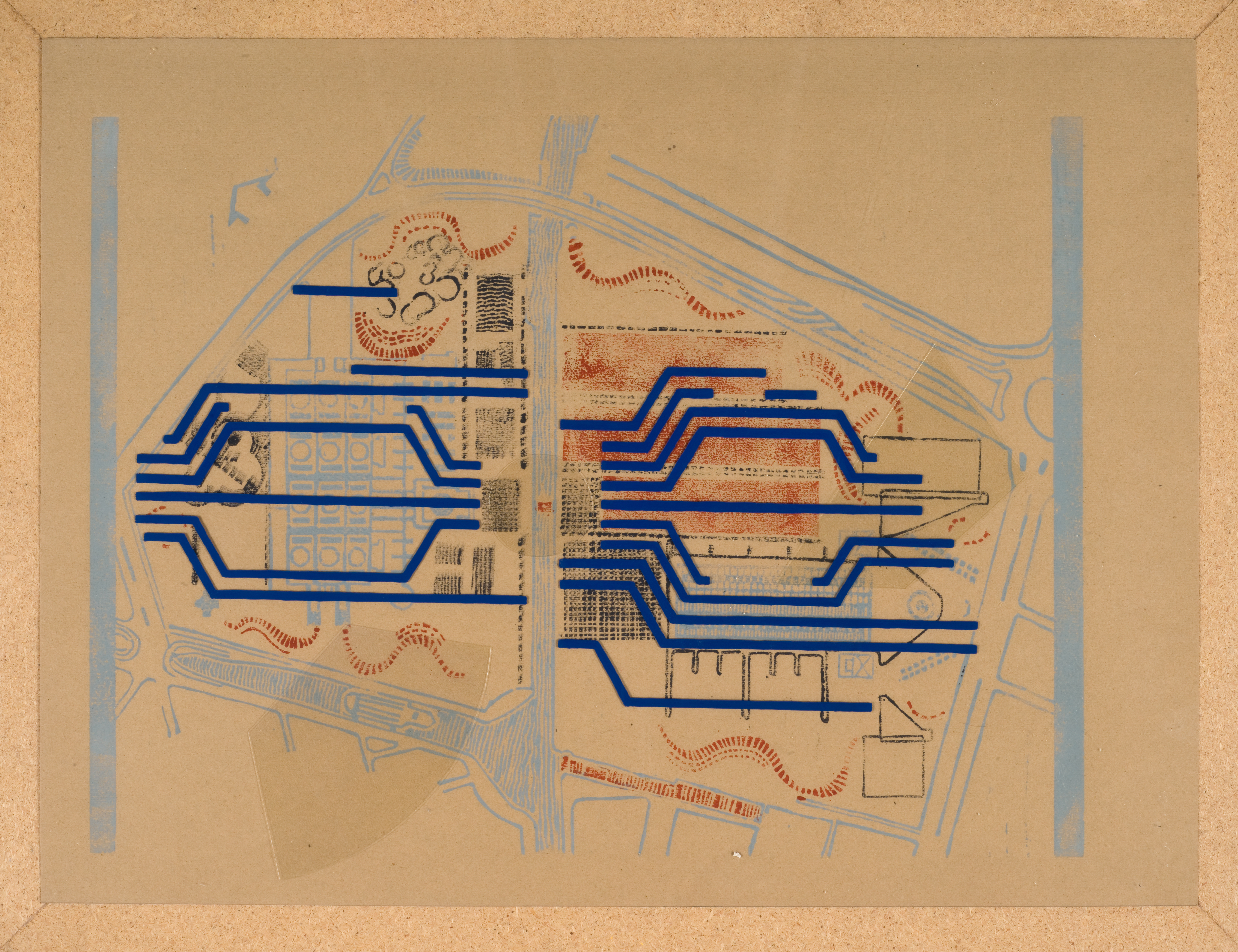

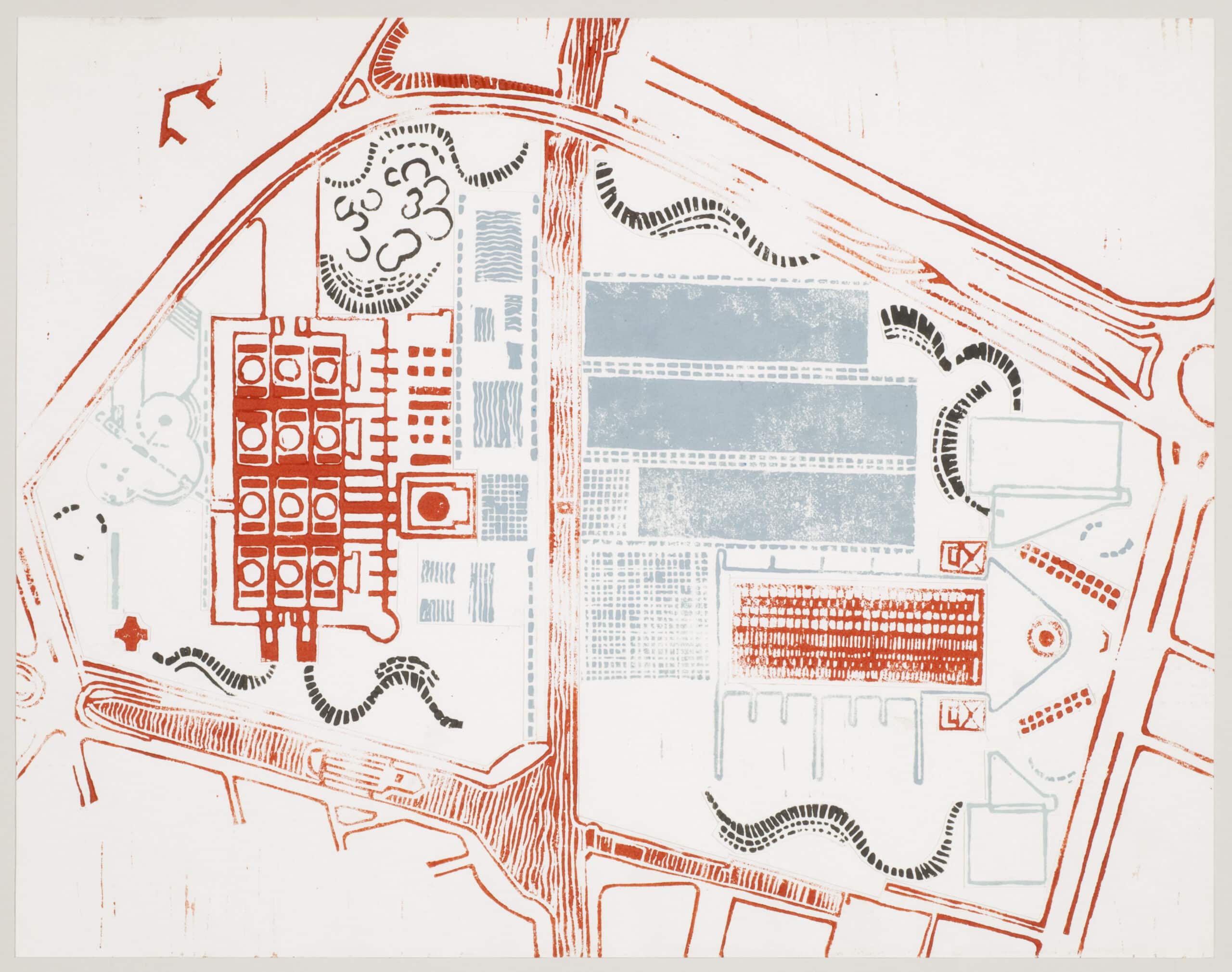

The lithograph held at Drawing Matter visually conveys this affect. A number of graphic objects occupy gently the park’s grounds. Light blue lines outline the existing urban shell: the roads and canals that limit the park’s grounds, the bulky structure that occupies the north area and the additional one off the centre in the south. Red and black figures pepper the site with new additions. Three main elongated patches unroll from the central canal while minor squared areas intensify the occupation on its flanks. Several winding lines draw the park’s edge. A composite dome-like object leads the north entrance, and a fine black line stretches and turns to explore the south region. An unyielding grooved pattern of blue lines hoovers above.

A related print with a swap of colour code is part of a series of 25 copies of development drawings at Cedric Price fonds, the Canadian Centre for Architecture, of various sizes and assorted media—including ‘crayon, possibly graphite, paper montage, correction fluid, coloured pencil and ink on reprographic copies, linocuts, translucent paper and paper.’[6] This archive’s catalogue refers to the project as ‘Parc’, and notes a certain distribution and mingling of its records within materials from other projects such as Serre, Serre (2), Rink, Aedes , Stratton and Non-Plan.[7] The following contributors are mentioned alongside Price: Establishment public du parc de La Villette (competition organizer), Elia Zenghelis (role unspecified), Bernard Tschumi (correspondence writer).’[8].

‘Bloody marvellous—just the right amount of detail with a mattering degree of partial judgement that makes “CP Projects Int” such an unbeatable agency for the biased good … CP HQ (Cedric Price Head Quarters) now undertaking rapid assessment of how little is needed & how much would spoil’.[9] Price greets the two-page survey sent by his ‘Site-Looker’ Joan Littlewood.

Rudi Kegel, Frans Schokkenbroek, Clemens M. Steenberg (eds.) (Delft University Press, 1983) 6,8.

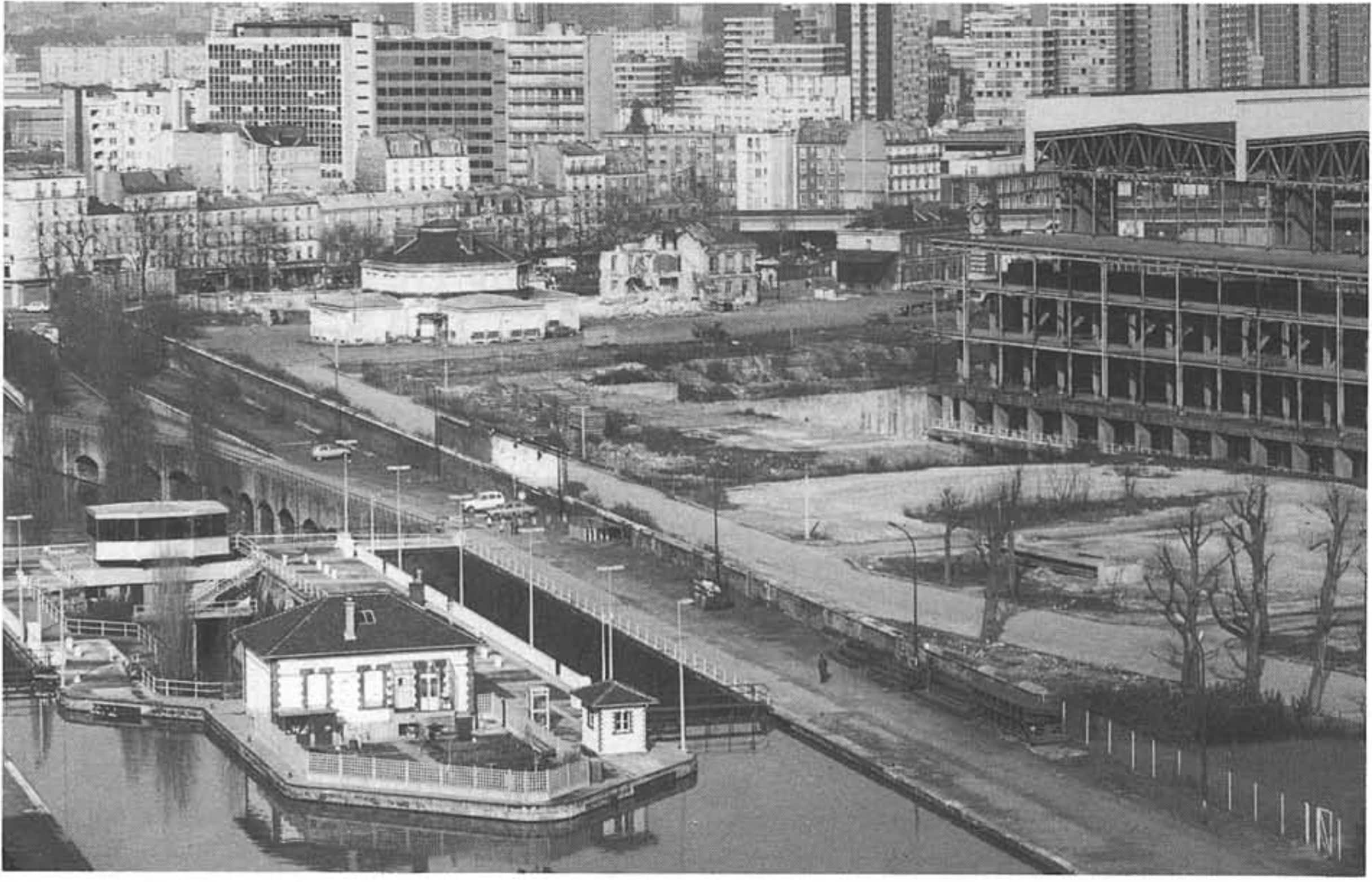

‘Map you have v. (very) incorrect. Site is cluttered with buildings’—Littlewood notes after visiting the competition site.[10] She diligently surveyed and reported to Price the inaccuracies found with regards to the ‘solid buildings’ and the ‘temporary structures’ present in the two main areas of the park, namely the ‘Grande Halle Patch’ and the ‘Musee Patch’—a suite of constructions which she claims to be ‘wrongly placed & out of proportion.’ On the Grand Halle Patch she notes, ‘there is ‘open access on all sides’, while the Musee—despite ‘only viewed from a distance due to footwear problem’—she claims to be an ‘enormous affair … resembles a dockland crane structure, 3 apparently disjointed overhead platforms supported by concrete pillars.’ She muses: ‘the work may have been abandoned when the government changed its cast. The large slogan “DO NOT CLOSE PARC VILLETTE” is fairly recent. There has been a lot of controversy. The scandal of money wasted on Parc V—obviously the Musee started and abandoned.’Inconsistencies recorded for the permanent constructions include: ‘2 large market halls, not 1; 2nd for sheep to left of Grande Hall on map’; ‘2 1890 Town Hall Type Buildings’; ‘the restaurant & pavilion des maquettes disused looks like 1880 County Railway Station’; ‘solid art, the fountain with Reckitt’s blue “Lions”. Temporary structures are also assessed for each of the main areas. Near the Halle she notes ‘a dirty old circus tent & 100 ft long canvas shelter for pony rides, old hoardings, wire or wood fences which fence nothing’ and ‘extensive smart portacabin type offices, one containing a dusty, broken model of a site project and another some characters—sitting it out.’ Littlewood wonders about the potential ‘fairy recent use of the area—a fair? Some kind of theatrical activity—?’ On her way to the Musee, a new small park on the bank of the canal does not impress her—‘two rows of sad trees.’ She then stumbles upon ‘the ugliest play structure viewed to date, bottom left on the map.’ Further caveats relate to the desolate state of the park, due to being cut out of its surroundings: ‘considering the number of kids who must be coped up in the housing blocks seen on all sides the emptiness is uncanny. I saw 2 people plus dog in the park. But access is v. (very) dangerous via dangerous roads … a labyrinth of criss cross sorties + tunnels.’ [11]

Yet within the unwelcoming environment, a number of facilities appear to hold some value for the future pleasure park: ‘Of many neighbouring restaurants, 2 allegedly famous’; ‘Large post office at hand’; ‘Plenty of parking space adjacent to site, might be kept’—and she advises Price further—‘site is very big, presenting dull vistas so design might involve upward expansion.’[12]

Structured around the temporary and permanent, these field notes scrutinise the capacity for change of this clogged and disconnected site. Despite the dull atmosphere recorded—dirty old circus tent, sad trees, ugliest play structure, dangerous roads, uncanny emptiness—Littlewood shares with Price a belief in the potential of design to transform its urban shell into a public pleasure ground over time, as anticipated in the positive valence of some catalyst-facilities—good restaurants, large post office, enough parking space to be kept. Ultimately, her notes reveal an active design sensitivity akin to Price’s penchant for delight.

The colourful lino print transforms this subdued site into an ‘urban lung’. Laboured erosion of matter—and clutter—thins out the datum of ink. Drawing by undoing. Large reservoirs of uncommitted land are carved out. Few winding lines and patches mark the paper with ink. Price’s intervention operates by stealth—‘how little is needed & how much would spoil’, he conveyed to Littlewood.[13] Price confirms this in his competition entry: ‘1.08. Many areas designated for variable activities are not detailed at this stage since it is felt that the management of the Park must have a large proportion of areas of different terrain and servicing, the use of which they can determine as the Park progresses.’[14]

Rolling entertainment, the plan multiplies. 25 copies are retained in the archive. They bond with adjacent bodies. Lines of different ages activate them—gantries,cranes, pipes, halos, booths, ‘”hello, goodbye” dispensers’ [15], ‘delight robots’[16], etc.These nimble contrivances become exchangeable tokens from the reservoir that is Price’s reversible practice, where the boundaries between projects dissolve. Lean and timely, Price’s life-long practice—operational-cyclical rather than historical-linear, as Banham advised in 1984 [17]—is crafted through such a vast repository of enablers of pleasure and delight, and entertained by the sustained conversation with Joan Littlewood.

Notes

- Cedric Price, Autumn always gets me badly, Architectural Association, November 1989. AA YouTube channel, 41:50. <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xaCYl9Y38X4&list=PLI1nDzeohfnn1USwgj87uX3mxVSsdxOTO&index=13>, [Accessed 28 October 2024].

- Ibid.

- Cedric Price, Cedric Price: The Square Book (Chichester: Wiley-Academy, 1984), 54–55.

- Price, The Square Book, 69.

- Ibid.

- Cedric Price. Parc: site plans, some used for cutouts, sketches, and notes. DR2004:1104, Cedric Price fonds, Canadian Centre for Architecture. https://www.cca.qc.ca/en/archives/380477/cedric-price-fonds/396839/projects/407605/parc#fa-obj-409685

- Cedric Price. Parc. 1969, 1982-1985, predominant 1982. Cedric Price fonds, Canadian Centre for Architecture. <https://www.cca.qc.ca/en/archives/380477/cedric-price-fonds/396839/projects/407605/parc> [Accessed 28 October 2024].

- Ibid.

- Letter from Cedric Price to Joan Littlewood, dated 11/8/1982. Folder Add MS 89164/6/50. Joan Littlewood Archive, The British Library.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Letter from Cedric Price to Joan Littlewood, dated 11/8/1982. Folder Add MS 89164/6/50. Joan Littlewood Archive, The British Library.

- Cedric Price, Park de la Villette competition entry. DR2004:1102:004, Cedric Price fonds, Canadian Centre for Architecture.

- Cedric Price, Park de la Villette competition entry. DR2004:1102:006, Cedric Price fonds, Canadian Centre for Architecture.

- Sketch, Cedric Price notebook no. 1. Cedric Price Collection, St John’s College Library, Cambridge.

- Reyner Banham, ‘Cycles of the Price-Mechanism’, AA Files 8, no. Spring (1985) 103–6.

Dr Ana Bonet Miró is a Senior Lecturer in Architectural Design at the University of Edinburgh, and a chartered architect. She is co-curator of the touring exhibition ‘Delightful Fun’: a Cedric Price Thinkbelt for our times (2024-25) and author of Architecture, Media, Archives: The Fun Palace of Joan Littlewood and Cedric Price as a Cultural Project (2024).