Conjunction and Incongruity

The word archive, meaning both the collection of documents and the building that houses them, is doubled in its meaning and it is not necessarily clear which one precedes the other. Drawing Matter Open Day highlighted in interesting ways the relation of causality between building and drawing as document or design, and the recursive nature of drawing in architectural practice.

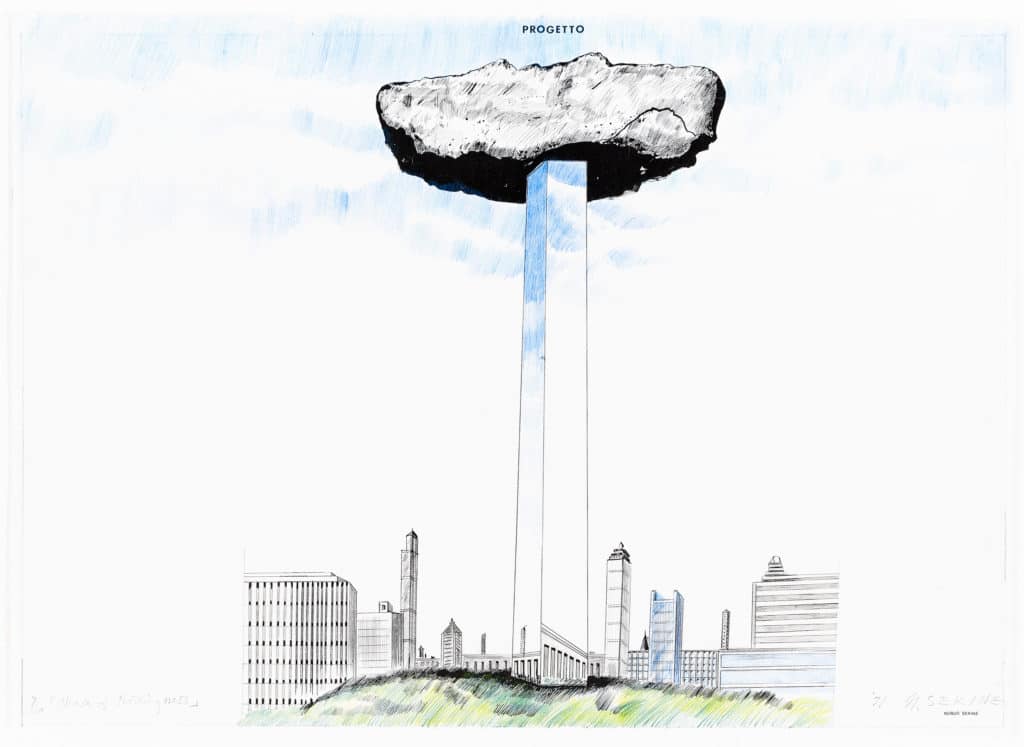

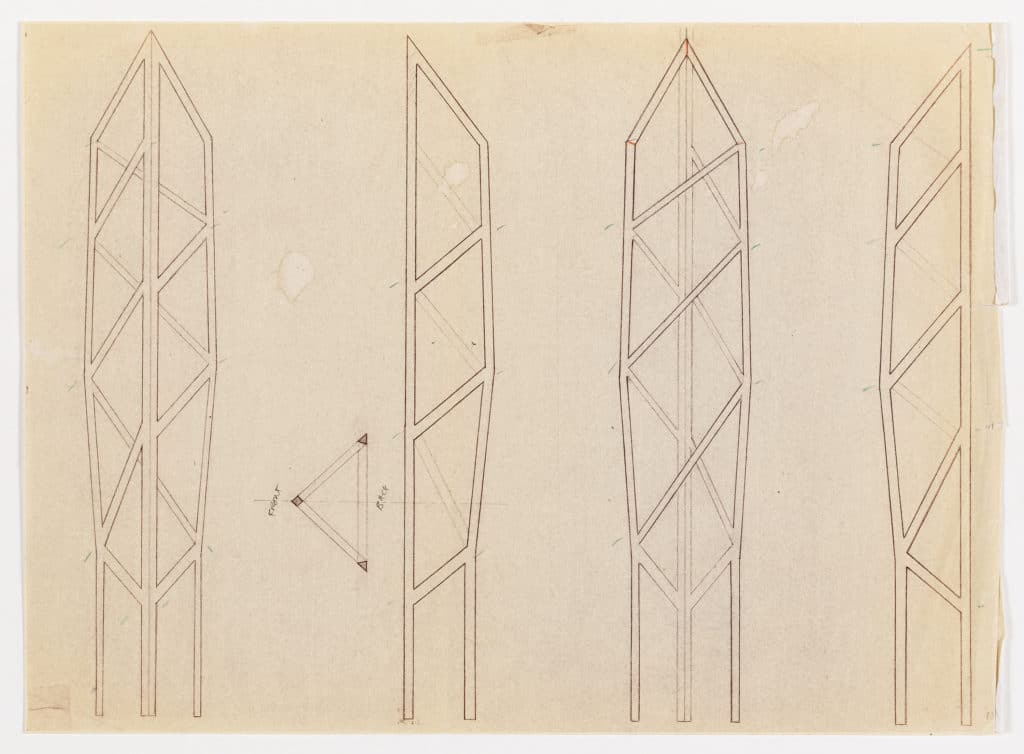

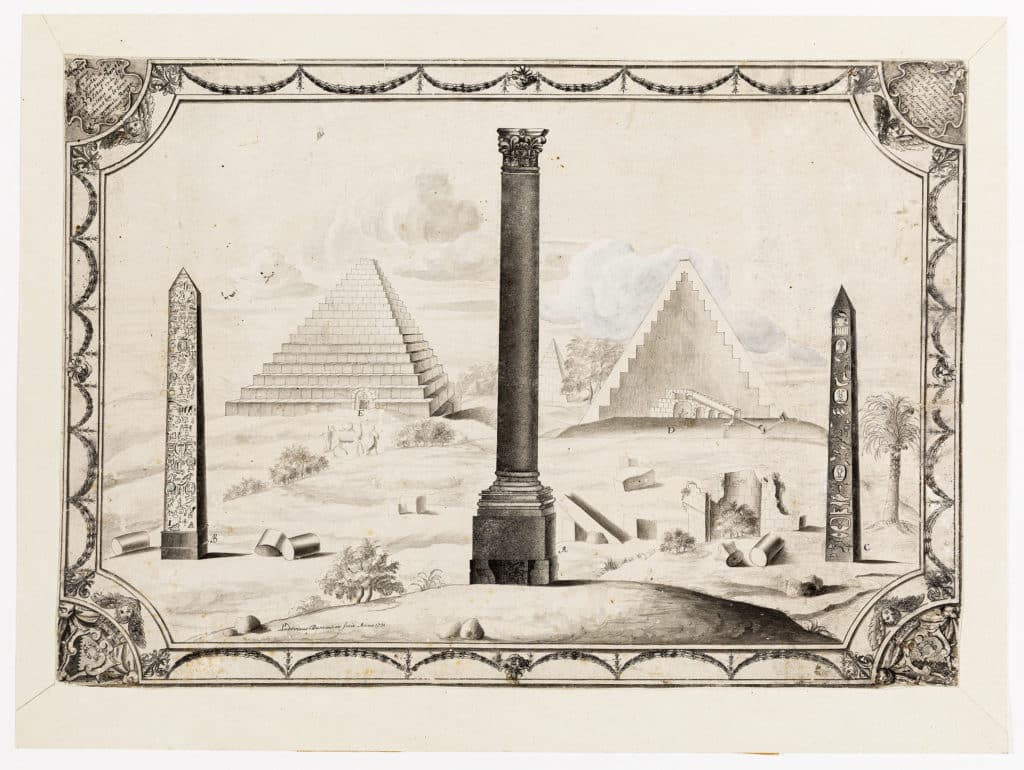

Drawing Matter is the title given to an architectural drawing collection assembled by the collector, curator and critic, Niall Hobhouse. Dating from the Renaissance to the present day, it includes architects’ sketchbooks, drawings and models. It represents projects that have been realised as finished buildings along with speculative ones that have never left the drawing board. The collection holds artefacts by both the anonymous and the celebrated such as an unknown album of drawings of Roman architecture in Italy circa 1731-1757 and a 106-page scrap book of detailed architectural drawings by Viollet-le-Duc. There are pages from the sketchbooks of the Swiss architect, Peter Märkli and a paperback booklet Working-Class Domestic Flats in Reinforced Concrete detailing a competition for five-storey flats organised by the Cement Marketing Co Ltd circa 1950 for which Lubetkin & Tecton won First Prize; Richard Sadler’s silver gelatin prints that show the Rebuilding of the Totally Destroyed City Centre of Coventry, 1948-50s; and a master plan by Cedric Price from 2002. There is a funny and fantastical work in Xerox copy, with ink and pencil, by Nobuo Sekine, part of the Mono-ha movement, titled Porgetto: Phase of Nothingness, 1971; Ludovic Dumontier’s 1732, Etude des Monuments de L’Egypte, in pen, ink and wash on laid paper is a study of Pompey’s column, Cleopatra’s obelisk and another obelisk, and the Great Pyramid, with decorative border and description in corner scrolls; and a contemporary obelisk by Peter and Alison Smithson, Obelisk for Hadspen House, a print with four elevations.

Drawing Matter aims to ‘begin with drawing itself’, and the ‘intentions with which the drawing was made, the conventions on which it depends, the real and imagined architecture it reproduces, and at what the designer’s hand might show which the building itself cannot.’[1] There is no doubt that it provides a wonderful resource through which to attend to this line of inquiry, but it was clear that the wider project that has arisen around the Drawing Matter collection merits consideration too. The online archive, the architectural commissions, the collaborations, and curatorial exhibitions suggests another line of inquiry into conjunctions and incongruity, the symbiosis of art and architecture, the rural economy, renovation, regeneration, gentrification and new philanthropy.

For the Drawing Matter Open Day visitors were advised to make a first stop three miles down the lane in the global art market phenomenon of Hauser & Wirth, to their Durslade Farm complex, a rural Somerset outpost to their other galleries in London, New York, Los Angeles and Zurich. This was no mere coincidence as the show there was curated by Hobhouse and presented some of his collection. Josephsohn/Märkli: A Conjunction presented the creative collaboration and friendship between an artist, the sculptor Hans Josephsohn, and an architect, Peter Märkli, who designed La Conjiunta in Giornico – the conjunction – in which to house Josephsohn’s reliefs and half-figures completed in 1992. Intended for sculptures, not for people, with no windows, no insulation, no toilets, the poured concrete walls work in conjunction with the highly textured surfaces of Josephsohn’s bronze sculptures. This pair’s friendship and La Conjiunta as a combined expression of both their practices gives an example one kind of symbiosis of art and architecture. Märkli, Hobhouse said, had been free in allowing his felt-tip, pencil and biro pages extracted from the sequence of a sketchbook to be displayed in the Hauser & Wirth show – where they were elevated to a fine art display as individually framed works – but had been more reticent to share those drawings that were for him the specific architectural designs for La Conjiunta. This, I speculate, perhaps indicates where Märkli felt the value lay in his drawing practice.

Architectures of display add value to artworks; this seems to be at play both in La Conjiunta, where Märkli was the architect, but also at Hauser & Wirth where the architect’s drawings became the objects on display. There was something incongruous about Märkli’s sketches next to Josephsohn’s bronzes in the renovated gallery space that, according to the architectural design concept, has maintained ‘the junctures between new and existing’. [2] I missed the conjunction but liked the inversion.

Another conjunction at play was that of these two re-purposed farm sites. As far as new and existing goes, it was Drawing Matter that preceded the arrival of Hauser & Wirth in the area by some years. Set amongst an array of converted and existing farm buildings in Somerset near Wincanton on a working farm formally part of the estate of the historic Hadspen House, the Hobhouse family had owned the Hadspen Estate since 1785. The first part to be renovated at Shatwell Farm was The Dairy House, re-modelled by Skene Catling de la Peña, as a retreat from the main estate. Other early commissions were intended for a number of follies at Hadspen, one of which was Obelisk by Peter and Alison Smithson. Hobhouse then further developed the complex of farm buildings on selling his 12-bedroom family seat in 2012, the same year that Hauser & Wirth bought Durslade Farm. One of those architectural commissions is the RIBA national award-winning building designed in 2012 by Hugh Strange Architects to house the Drawing Matter collection itself. Drawing Matter Open Day included in its display of works the drawings and model that Hugh Strange made of the design for The Archive.

The Archive at Shatwell is a space for handling and reshuffling the drawings. In contrast to the aesthetic of display at Hauser & Wirth, the presentation at Drawing Matter felt contingent and exploratory, presented in their archival sleeves and inviting reorganisation. In fact the built environment of the site has a similar feel. Many of the structures are temporary as regards planning, such as library pods in shipping containers, which give the sense that they would be open to re-articulation with the next curatorial perspective. Alison and Peter Smithson’s Obelisk is also a case in point. It was conceived for Siena in 1984, but built as a folly for Hadspen in 1994, then relocated to Shatwell on the sale of the Hadspen Estate. The Smithsons’ Obelisk connects this rural site to ideas of regeneration and current housing crisis through association with the architects’ recently demolished and much debated Robin Hood Gardens, a mid-twentieth century solution for social housing. It is as if the ensemble of architectural elements at Shatwell has been curated as an experiment in town planning over-laid upon a working farm.

Niall Hobhouse’s Drawing Matter is like a wonderful folly in the best and broadest sense. Follies occur as a surprise in the landscape of a country estate and the architectural folly employs humorous excess for the purpose of architectural speculation freed from utility. Working to re-erect Obelisk in 2016 at Shatwell Farm, the Smithsons’ grandson, Lucas Wilson, described Hobhouse as a ‘hugely generous patron of architecture’. The construction of follies also has a history in supplying work to the rural poor. In this genealogy Drawing Matter could be thought of as a new kind of philanthropy. In comparison, it struck me that Hauser & Wirth at Durslade Farm was an example of a commercial gallery taking on the remit of publicly funded arts centre or museum – even to the extent of inviting non-obligatory donations at the door – in an area of the country poorly served by public galleries.

The Hauser & Wirth Somerset Durslade development had fully incorporated all previous elements of the working farm into a slickly designed experience, whereas the Drawing Matter site at Shatwell Farm felt refreshingly open – on the approach a hand-written sign pointed the turn off, the farmyard included piles of material that was hard to distinguish between the yet-to-be used or the already-discarded, and a charming mobile café served home-made cake, teas and coffees courtesy of the organisers. The working farm credentials at Shatwell Farm are attested to by the young live cattle that are housed in the Cowshed by Stephen Taylor Architects (who also designed the Hay Barn) and on the open day we as visitors became part of the picture as we looked on as the calves ate hay.

It is interesting to wonder what part these two ventures might play in regeneration and the rural economy. The Drawing Matter archive includes Paul Piot plans for an ‘Abbatoir and Boucherie’, circa 1828 -1840, certainly a type of architecture integrated into rural farming economies. In a glass cabinet in their foyer of Hauser & Wirth hang slabs of meat, reminiscent of YBA artwork. It carries the notice ‘this is not art’, although in the 1990s it may have been mistaken for a Damien Hirst. It was artwork that looked like this that made Hirst wealthy enough to commission the building of his own exhibition space: Newport Street Gallery in Lambeth, London by architect group Caruso St John winning the 2016 RIBA Stirling Prize. The proper significance of Hauser & Wirth’s meat cabinet, we were told, is as a proof of the credentials of this site as a working farm – a few short steps away in the restaurant and we viewers can become consumers of that beef.

Hobhouse offers the conviction that, in the South of England at any rate, there is a false and exaggerated difference between the rural and the urban. Hobhouse’s creation of a collection, and his process of commissioning architects are both forms of curation as a practice of conjunction and incongruity. Any personal collection is motivated by the interest and enthusiasm of the collector. As such any collection can appear to contain incongruities – until one considers the totality as an expression of a biography or as a kind of portrait. Along these lines, Sadler’s print of Rebuilding of the Totally Destroyed City Centre of Coventry, 1948-50s showing the devastated cityscape ripe for town planning, might recall the razing to the ground of the Hadspen Parabola walled garden. This flattening was initiated by Hobhouse in aid of a competition for new garden designs for the site that were never to be realised. Drawing Matter has developed Shatwell Farm as incongruous conjunctions of urban and rural, as a kind of folly on the scale of the town plan, it has the appearance of a civic square marked with an obelisk, the agora, a meeting place and place to talk, in the vicinity of its civic buildings – its library and its archive. Drawing Matter returns the building to the drawing – Hobhouse curated Josephsohn/Märkli: A Conjunction by returning Märkli’s La Conjiunta to the pages of the architect’s sketchbook, Hobhouse has turned his Hadspen House into a collection of architectural drawings and its established and famous Parabola garden into a set of open-call garden designs. Drawing Matter ‘begins with drawing itself’ but in a recursive move also returns architecture to drawing, which is also like a kind of escape from the finitude of the built.

Polly Gould is a Postdoctoral Research Fellow in Design-led Architectural Research with ARC Architecture Research Collaborative, School of Architecture, Planning & Landscape, Newcastle University. She has lectured on fine art and architecture programmes and is a curator and artist showing with Danielle Arnaud.

Author’s address: Polly.Gould@newcastle.ac.uk

‘Conjunction and incongruity’ was first published in arq, volume 22, number 1, 2018.

– Iris Moon