Dance Dance Revolution

In 1788, the art theorist and critic Quatremère de Quincy devoted a long entry of the Encyclopédie méthodique to the arabesque, ‘forms of ornament that are often the most capricious, fantastical, and imaginary, whether in sculpture or painting, that architecture employs in the decoration of walls, panels, door-frames, pilasters, friezes, and sometimes even on vaults and ceilings.’[1] For this serious architectural theorist obsessed with classical origins and absolute order, arabesques posed a semantically loose and visually messy topic. Possibly originating in the Islamic prohibition of figurative images (but already found in classical antiquity), arabesques eventually came to cover virtually all of architecture’s surfaces. Seeking to define this ornament with multiple names—moresque, grotesque, arabesque—and many points of origin, he writes that ‘one can only define the arabesque in calling it the abuse of ornament.’[2] Particularly egregious was the ornamental upending of architectural propriety. He upbraided those who used arabesques in spaces that required respect and gravity, for they would offer nothing more than ‘a mix of discordant subjects, & objects incompatible with [respectful] sentiments.’[3]

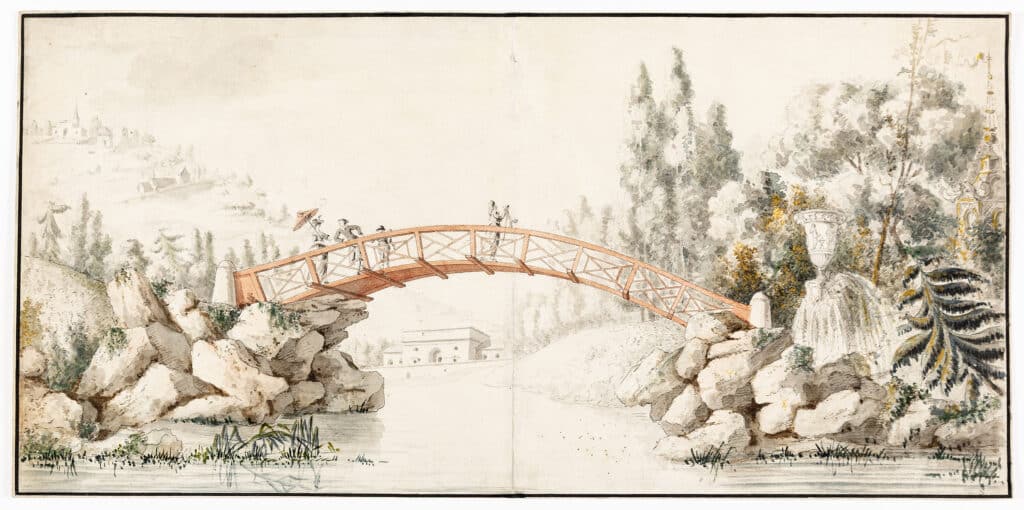

Few architects heeded Quatremère de Quincy’s advice. In late eighteenth-century Paris, arabesque decorations snaked through nearly all of the residences constructed in the city’s great building boom that took place from the end of the Seven Years’ War in 1763 to the start of the French Revolution in 1789. The cultural critic Louis Sébastien Mercier described enormous buildings emerging ‘from the earth, as if by enchantment, and new neighborhoods are composed of nothing more than hôtels of the greatest magnificence’.[4] At the top of this ancien régime speculative building heap and the viral explosion of arabesque sat François-Joseph Bélanger. Known as the architecte des folies and the great rival to Alexandre Brongniart and Claude-Nicolas Ledoux, Bélanger made no bones about being the builder to the great, the powerful, and the gorgeous. Purchasing the title of architect to the comte d’Artois, Bélanger proceeded to construct lavish residences (among which his counted his own) and design outlandish pleasure pavilions and grounds such as Bagatelle and the Folie Sainte-James. He did not manage to travel to Rome like the other academically trained French architects. Instead, he booked passage to England, where his imagination fed off the works of William Chambers, the Adam brothers, and picturesque English gardens. A playboy (and sort of a cad), he dated opera singers and dancers. As a shrewd architect, he took financial risks yet always maintained a keen interest in infrastructure projects, buying properties scattered around Paris (notably the triple townhouse rental property on the Rue St. George).

As a property developer, Bélanger accrued wealth by purchasing real estate in new neighborhoods, including the Chausée d’Antin, where he would cover the house of his lover and future wife, Mademoiselle Anne-Victoire Dervieux, in arabesques. In 1785, Dervieux had asked Bélanger to update the lavish residence that Brongniart had built for her in 1778. The first advice he gave was to buy adjoining properties to expand her domain. Next, Belanger fixed the roof, giving Brongniart’s flat one a pitched profile made of copper cladding. He also added two wings towards the garden side of the property. His most significant and well-publicised additions were the octagonal bathroom and conjoined circular boudoir in the east wing, and the dining room on the west side wing. In 1789, at the start of the Revolution, he updated the décor.

As a petite maison, Dervieux’s seductive residence was an example of the new building typologies that emerged in eighteenth-century libertine Paris. Somewhere between a grand hôtel and a rustic getaway, the dancer’s house was located in the Chaussée d’Antin, an undeveloped neighbourhood on the northwest outskirts of Paris where architects, property developers, speculators, and rich clients paid to play with the social and architectural norms of the period. Her house also functioned as a form of publicity. Dervieux, who began her career as a dancer and singer onstage, gained notoriety as a courtesan to the rich, powerful, and wealthy. While most eighteenth-century interiors were spaces of intimacy closed off to the public, the publicity generated around the petite maison in the literature of the period provided a narrative for ‘kept women’ like Dervieux to generate income and publicity from spaces intended for intimate encounters. Tickets were sold to curious visitors, stoked by reading libertine novels such as Vivant Denon’s Point de Lendemain or Bastide’s La Petite Maison, where architecture was an active agent in plots of seduction.

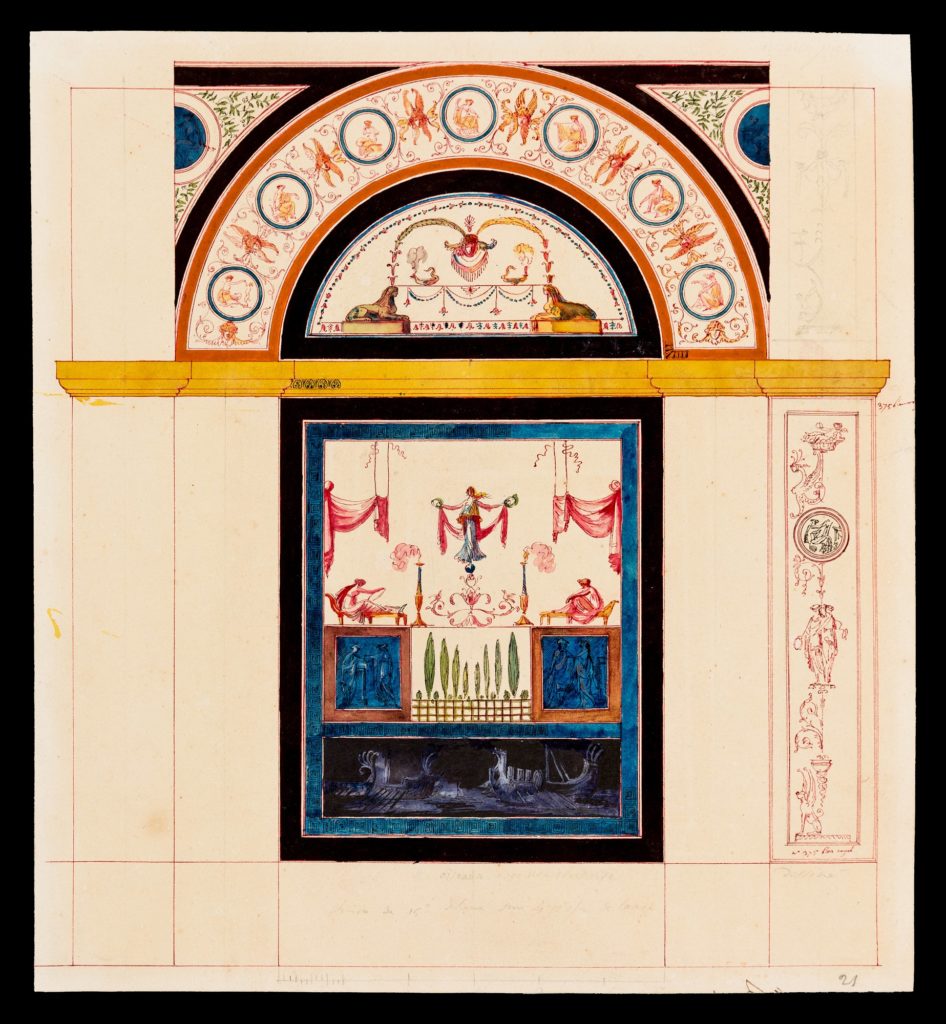

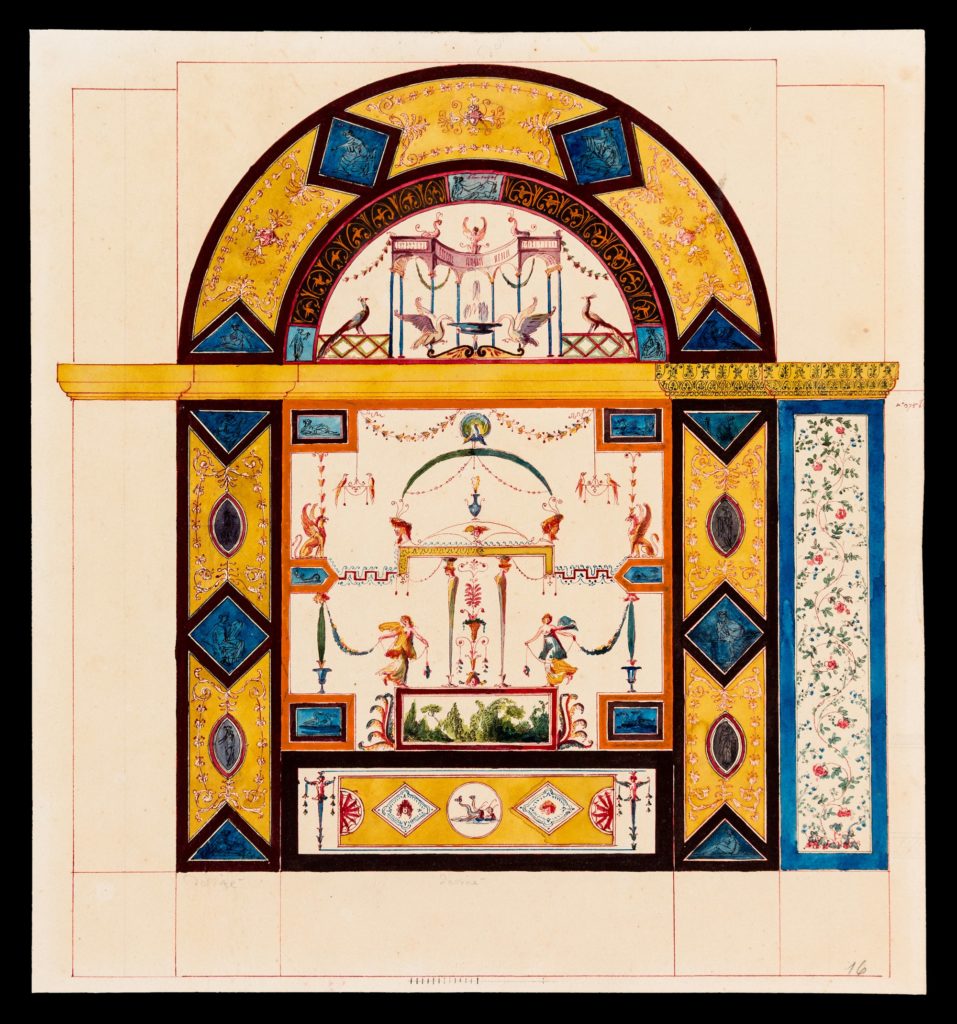

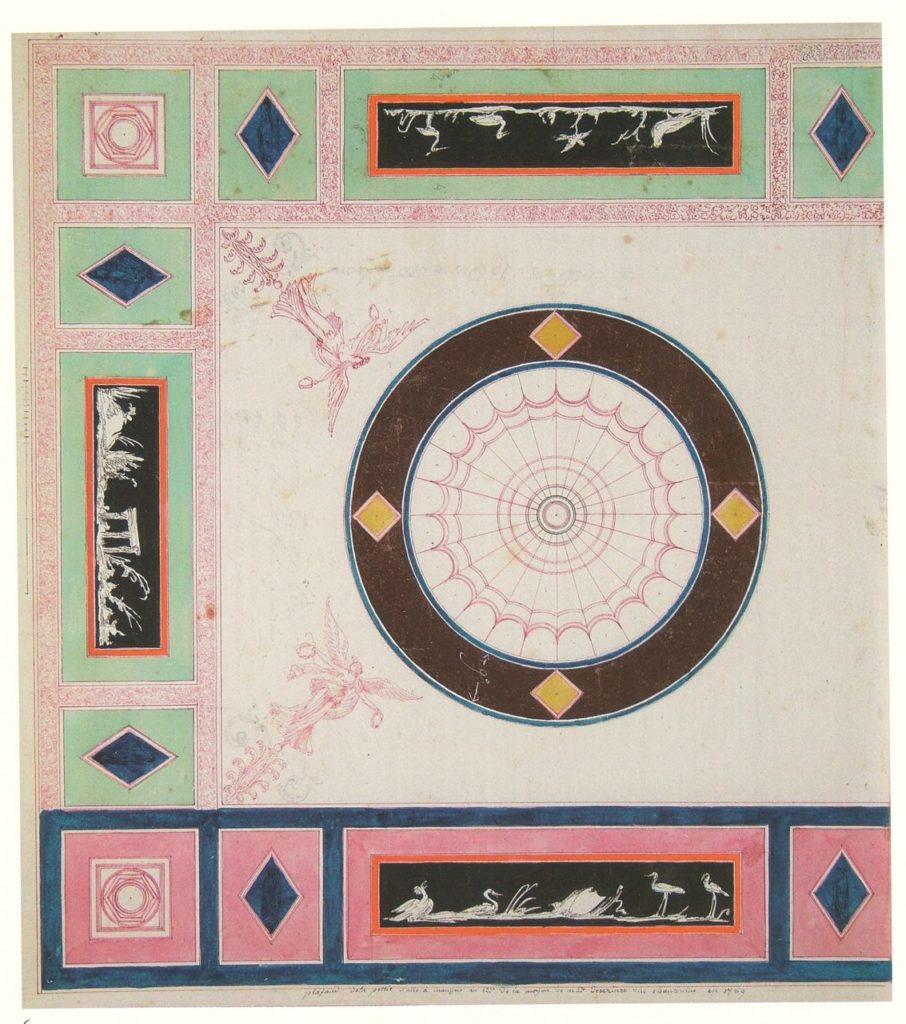

Colour was a key component of seduction, and is central to the drawings for Dervieux’s interiors, all that remain of this destroyed residence today. For example, a design for the ceiling includes a central circular motif in the style of a roman sail vault by Bélanger, in a French nod to Robert Adam, along with three rectangular vignettes of birds set into the edges, which alternate with a diamond pattern inset into rectangular segments. The drawing also features Belanger’s unusual use of pink ink to sketch in additional sections, in contrast to the somber tones of brown and black typically employed at architectural firms.

Bélanger thinks in colours. Pink is used to structure and comment, as well to fill in and shape. More than the precedents, typologies, and lesson plans that drove the thought patterns of academic architects, he thinks in terms of textures and materials. This colorful sensibility extends to the range of tones found in the drawings proposing Pompeian wall elevations. As Peter Fuhring noted, ‘At first glance, the colours applied to the drawings are surprising, but once they are compared with the wallpaper of the period, it becomes evident that the search for intense colours and surprising colour contrasts was part of the sought-after goal.'[5] Wallpaper, in fact, appears to be the primary structuring device in a number of the drawings. And much of the arabesque decoration at Dervieux’s house may in fact have been painted as wallpaper designs by an artisan such as Pierre Cietti, as has recently been suggested by Christian Baulez.[6] So Bélanger thinks in illusions too. A number of the more colourful elevations with trompe l’oeil effects, particularly the arabesques that feature landscapes against a black background set into vignettes, appear to be by Cietti’s hand executing Bélanger’s vision. Cietti (or Cietty), who arrived from Italy in Paris in 1778, worked on a number of residential projects for Bélanger, while also serving as chief painter at the wallpaper manufacturer Reveillon and later Jacquemart et Bénard, before he was guillotined in 1794.

Accused of being suspects for their ties to the nobility, Bélanger and Dervieux were arrested on 15 pluviôse II (February 3, 1794) and thrown into jail at Saint-Lazare. Bélanger occupied cell number 39 on the third floor, with the former architecte des folies incarcerated near the cell of painter Hubert Robert. Both had worked on Bagatelle. Once known as ‘Robert des ruines’, the painter bided his time behind bars by painting on plates and selling them to English tourists. The architect and the dancer were eventually transferred to Sainte-Pélagie prison before being released in August of 1794, after the fall of Robespierre. Prison does things to a man. And so this inveterate playboy finally decided to settle down with Dervieux and marry her. Even on the other side of the Revolution, Bélanger remained very much a man of the ancien régime. His biographer Jean Sterne wrote that ‘The old man, always haunted by the mirage of the past, remained faithful to the tradition of the eighteenth century.’[7] Meanwhile, the world around Bélanger was in the midst of change, as the arabesques of the past were replaced by the work of a new generation of architects shaped by the events of 1789. There was no time to dance when you had to build the future.

Notes

- Quatremère de Quincy, Encyclopédie methodique (Paris: Pancouke, 1788), 73.

- Ibid, 74.

- Ibid.

- Louis Sébastien Mercier, Tableau de Paris (Paris: Mercure de France, 1994), Vol. 1, 224, “On bâtit de tous côtés.”

- Peter Fuhring, François-Joseph Bélanger (Paris: Didier Aaron & Cie; Galerie de Beyser, 2006), 12.

- Christian Baulez, “De Bélanger à Pierre Cietty, histoires de papier peint,” paper presented at the François-Joseph Bélanger colloquium, Paris, INHA, December 7, 2018.

- Jean Sterne, À l’Ombre de Sophie Arnould: François-Joseph Bélanger, Architecte des Menus Plaisirs Premier Architecte du Comte d’Artois (Paris: Plon, 1930), vol. 2, 361.

– Matt Page