Drawing Out, Drawing In: Cartographies for ‘Out of the Sea’

The provocation for this essay is Drawing Matter’s own: ‘we take the word “drawing” to be as much a verb as a noun…’ Drawing describes an act and a thing: both a process and the outcome of that process. There aren’t many English words like it, and many of them are to be found in the creative realm — a painting, a making, etc., parting in one’s hair, maybe; a being.

There are so many things that fascinate me about the word. One of which is that even the noun-form of drawing — the thing or artefact — is captured: as an -ing word, it is ongoing, still in the act. In this sense, maybe a drawing is never inherently complete, just as a being is an entity going about the business of existing in a durational manner. John Berger suggests that the completion of an artwork relies on the viewer; that it is finished ‘not when it finally corresponds to something already existing… but when the foreseen ideal moment of its being looked at is filled.’ [1] So, these artefact-as-ing words are not only creative but perhaps hold participatory potential.

Drawing is also a fascinating word because of its two-way meaning: to draw in the sense of making marks entails a putting-down, a deposition of matter, like graphite or ink applied to a page. But it is also a pulling force, as with the drawing of blood, or breath. These meanings are almost opposite – one inward, one outward. And they are paired, constantly and reciprocally in the process of making a drawing: we put down marks, and as we make them we draw from memories, so that with each line we call forth knowings and preferences, other lines we have seen and drawn. Once they are on the page we see them objectively, and they spur new, responsive marks, so we put down some more, and reach into our minds again. We continue to draw out, draw down, draw from, and draw into and on. These processes are embodied and inseparable.

When we draw places, we draw objects and masses and lines and textures out of the landscape. We identify contours and features to transcribe, and what is between them is edited out. As Manuel de Solà-Morales beautifully put it, ‘to draw is to select, to select is to interpret and to interpret is to propose.’ [2] We draw from the world and we transpose to the page, and in doing so we plot a new fiction. He said another thing about the relationship between drawings — in particular, cartographies — and the place they describe: that ‘this “fiction” might effectively be its proposal’. [3]

In this drawing set I was working consciously with fiction and with the subjectivity of mapping, and the confluence between the knowledge that map-making is mythic, and that it is propositional. The drawings are a Covid-19 story, a project that came about through trans-continental collaboration. They involved responding to a landscape I have been to before but couldn’t revisit. I was supplied with that place’s digital simulacrum: a point-cloud scan. The capacity to draw from the model (an array of nodes plotted by a scanner) and from memory made for two divergent but equally fictive and flawed, reservoirs of information.

My friends, who own a point-cloud scanner, returned from Myanmar to isolate on their property in Quindalup, in the South West of Western Australia. With regional borders closed, they began to scan Canal Rocks — an incredible coastal granite formation with two, cruciform slashes that run through it. They asked me if I would create drawings from their point-clouds for an exhibition called ‘Out of the Sea’. I am from Western Australia but have been living 4000 kilometres away in Newcastle, New South Wales, for the last two years. My history, my family and friends, and my lover remained in WA with a closed state border between us. As I began to work with the scan, other artists were brought into the project. We were all sent the same data to work with in our own media. I asked whether I could have the raw model, and I found myself wandering around it in digital space.

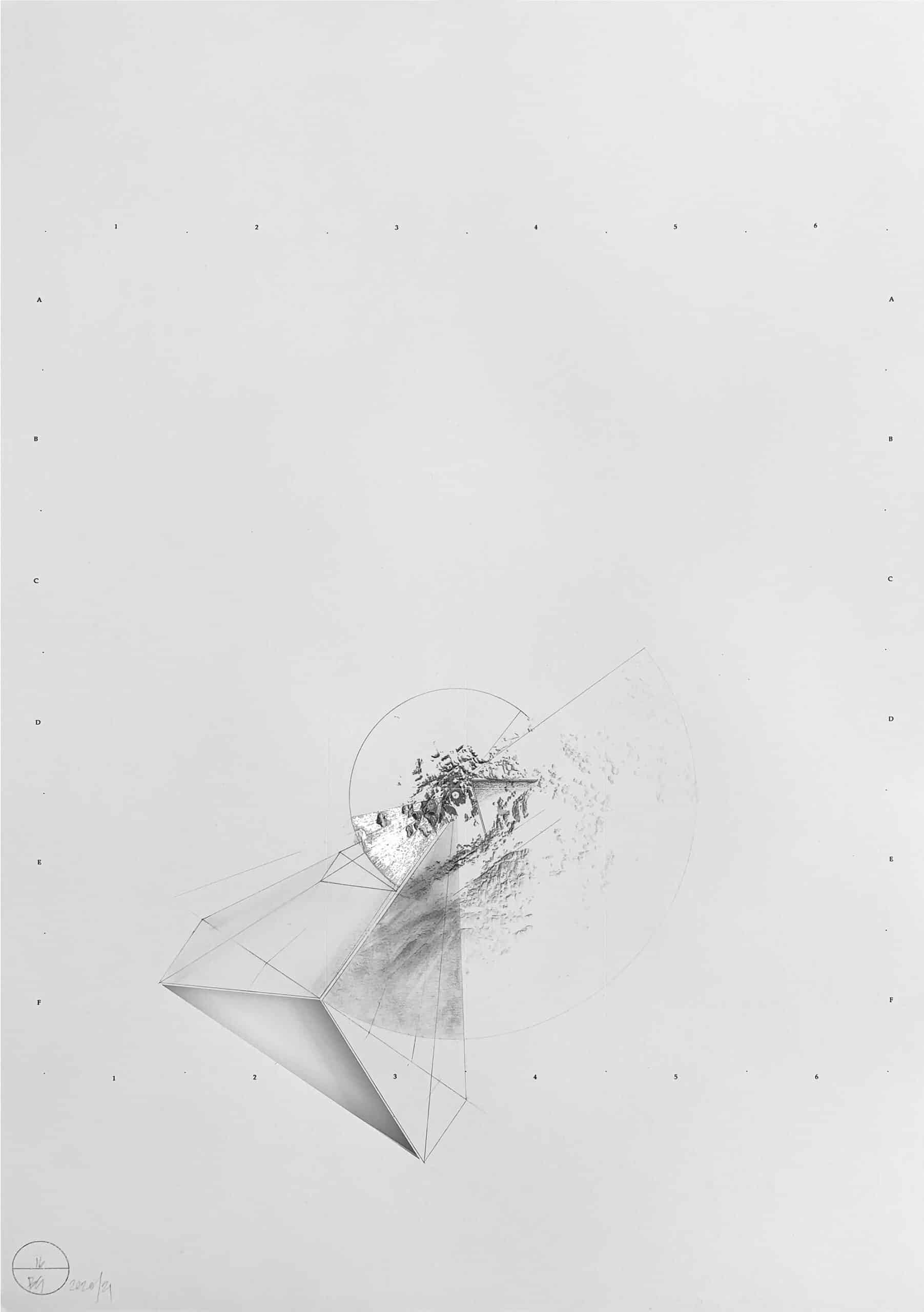

What I find compelling about a point-cloud is that it makes a comprehensive casting of the landscape from a certain distance, but the closer you wheel toward any part of it, it disintegrates, and the space between each mapped particle emerges. The presence of the landscape in the model is riddled with absence, and this felt significant in terms of my inability to reach the site, in turn constituting the intangibility of home. I thought about the strange relationship between longing and lines (as elongated points) as things that become longer. Distance and absence and void get interwoven.

This cloud was made up of seventeen scan locations stitched together. Taken individually, each contains only what can be seen, or more accurately, touched, by one, biased, lens. Each scan, then, has its umwelt, which, looked at from any other angle, revels the view-shed or the gaps in its world view. [4] And it cannot see water. Water is the force that generated this landscape: that shaped the peaked and creased rocks, and that surges through the canal in rough seas and creates thrilling reverberations through the granite canyon beyond. It created the place, but it is missing from the scans. It is the ghostwriter of the data.

So here was a fictional representation of a real place, sent across the country like a letter from home anticipating a response, to me, in Newcastle, where I walked and took my troubles to my own sea. Two cartographic projects came to mind. The Bellman’s Map, from Lewis Carrol’s The Hunting of the Snark, catching within its borders a featureless sample of watery nothing, and Mike Webb’s Temple Island, the drawing set that took the laws of perspectival view-sheds and made from them a phenomenal world. [5]

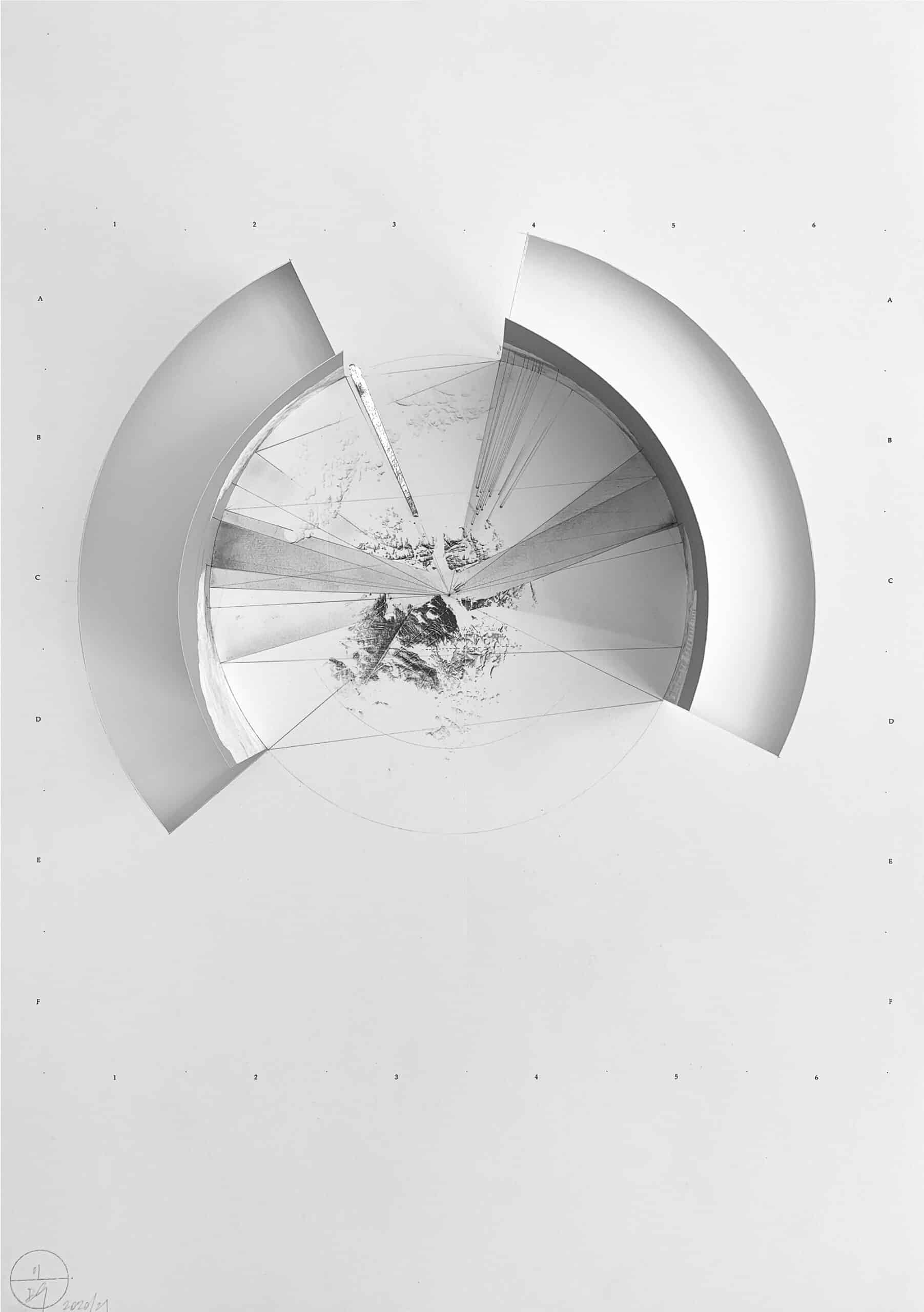

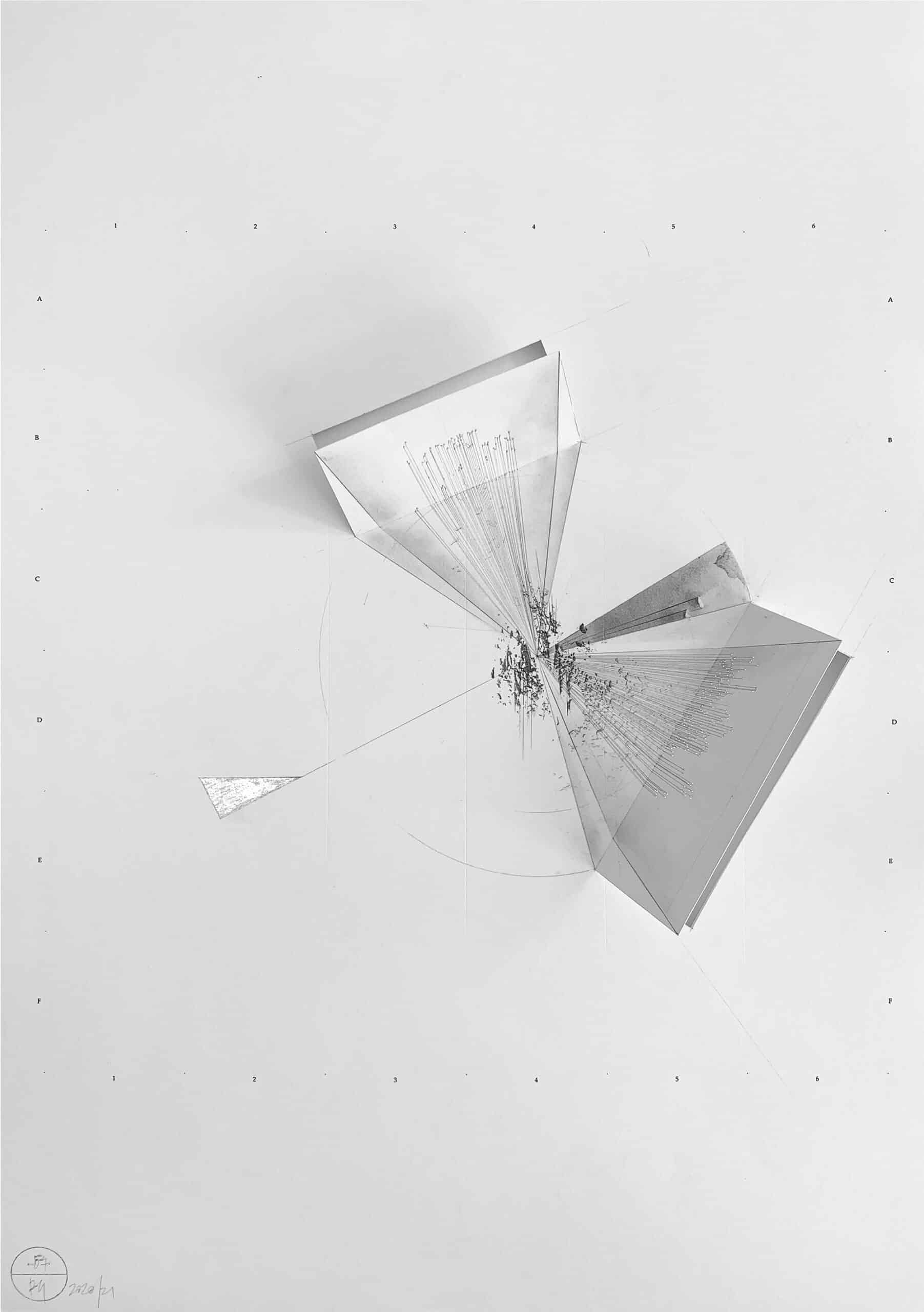

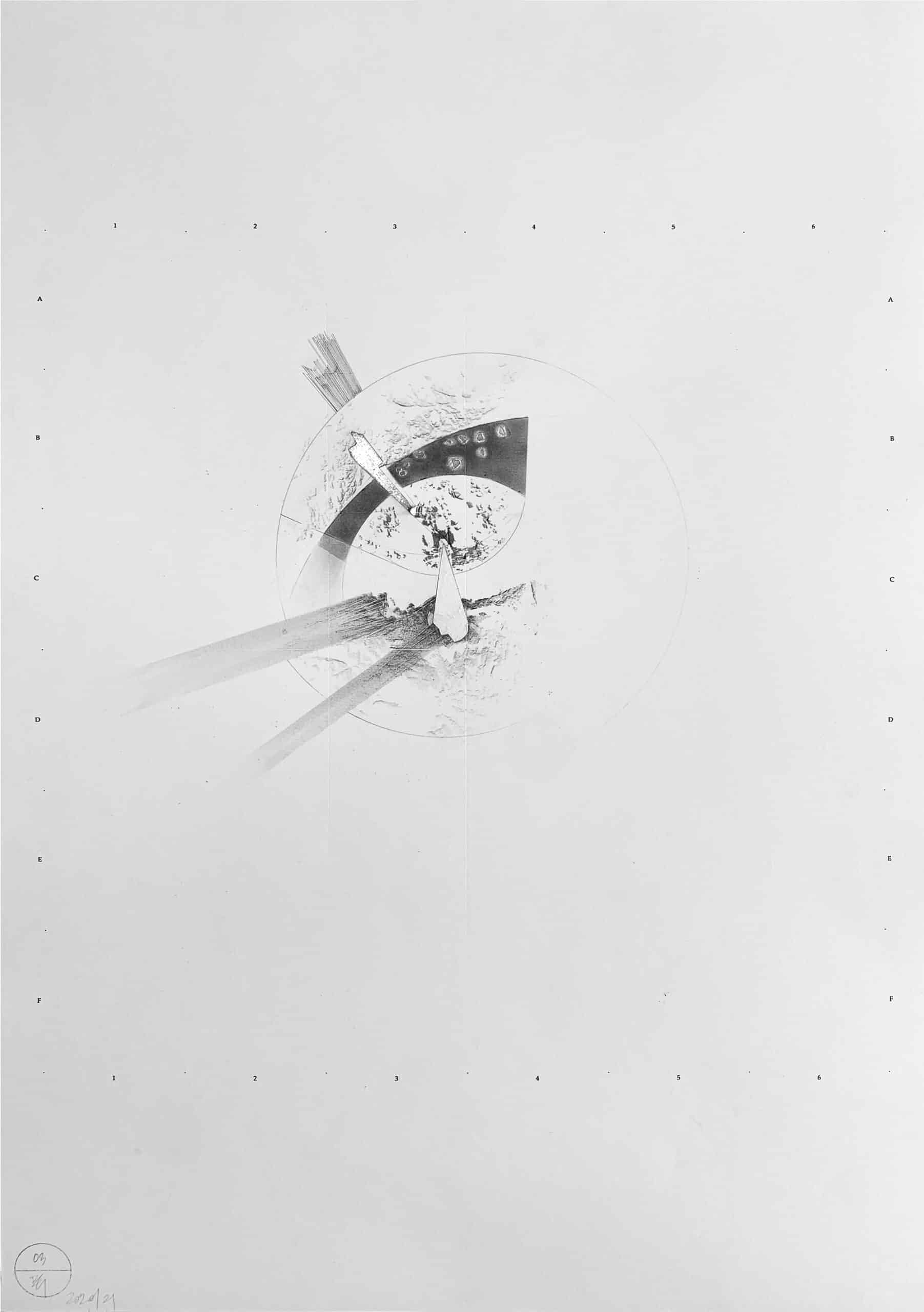

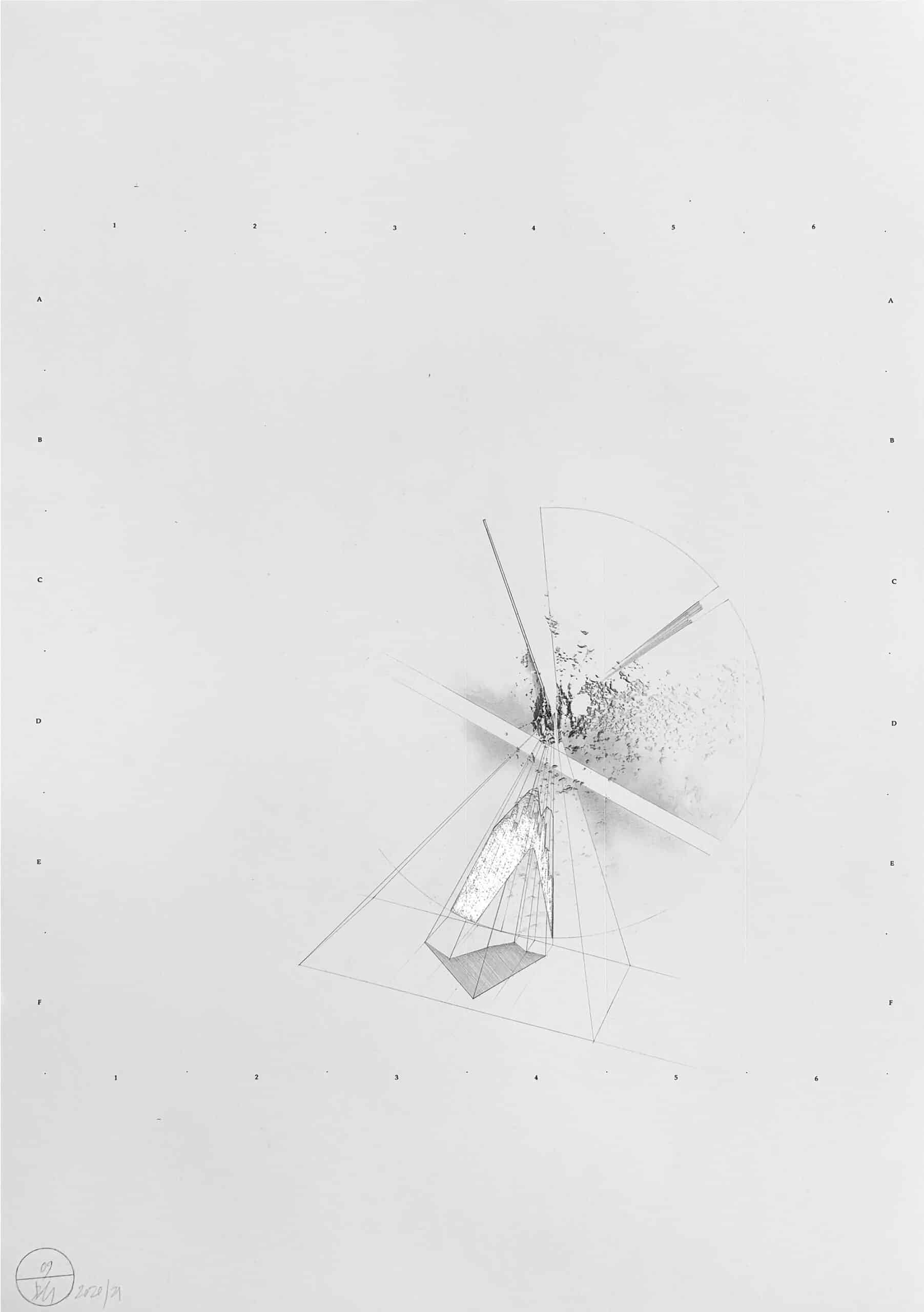

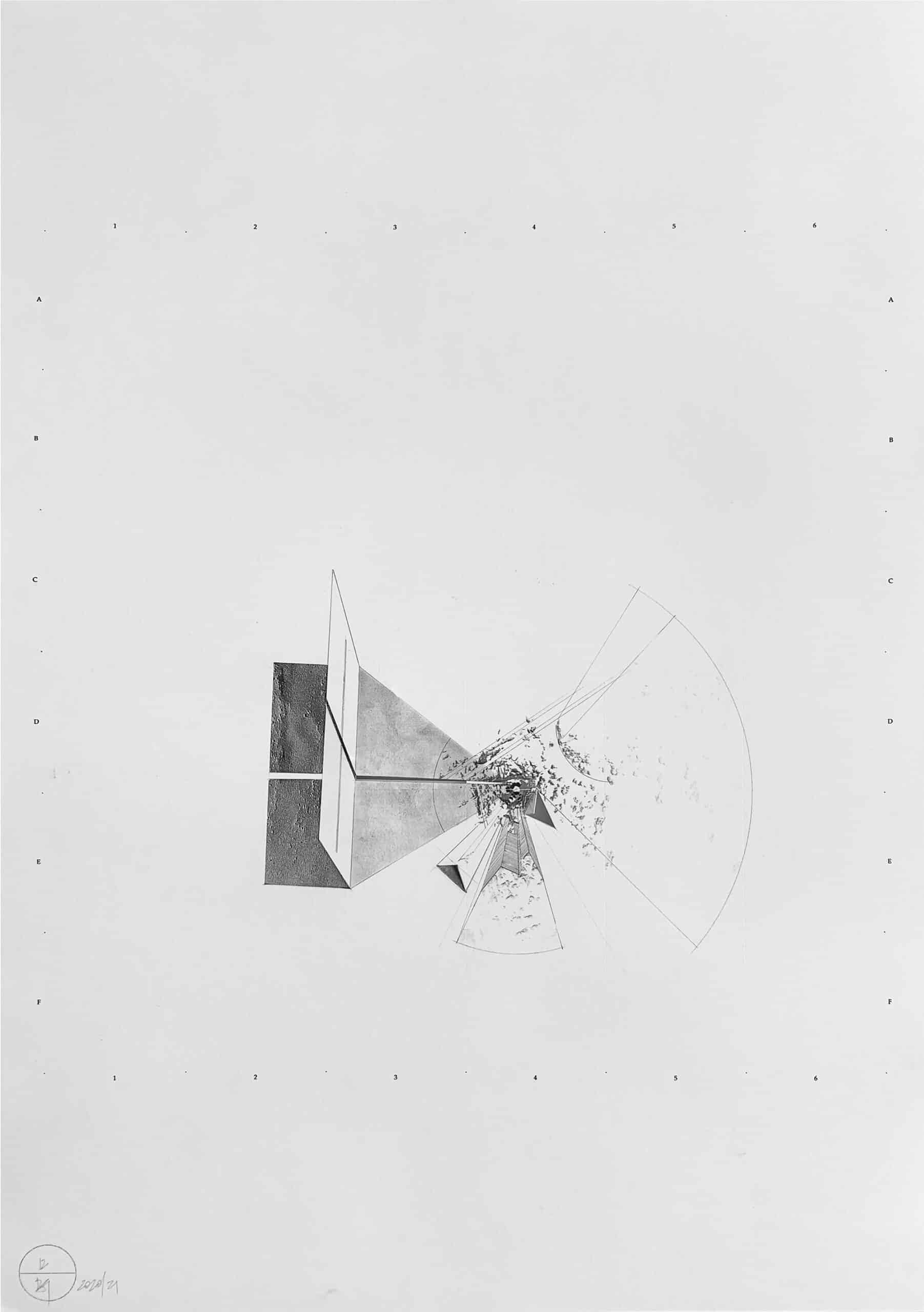

I stripped the point-cloud of its photographic data, leaving white nodes in grey space. I looked at each individual scan in plan, perhaps the most abstract of views, and imagined what each spherical, wandering eye could ‘see’ without recourse to the model or the benefit of perspective. I located topographic features, drew them out of the page, named and exaggerated them, as if constructing stories from constellations, inventing forms and connections. I made seventeen initial maps. They had annotations like Wrinkles, Atoll, Tower. I then appraised them with the model open, this time panning through it in perspective to negate or confirm what I had read. Some features strengthened and others were cast off, through a set of ‘re-mappings’ — drawings over photocopies of the first maps that contained new marks, edits, and the occasional note saying no. These were imagined into a final set, envisaged as deep drawings, or thin models.

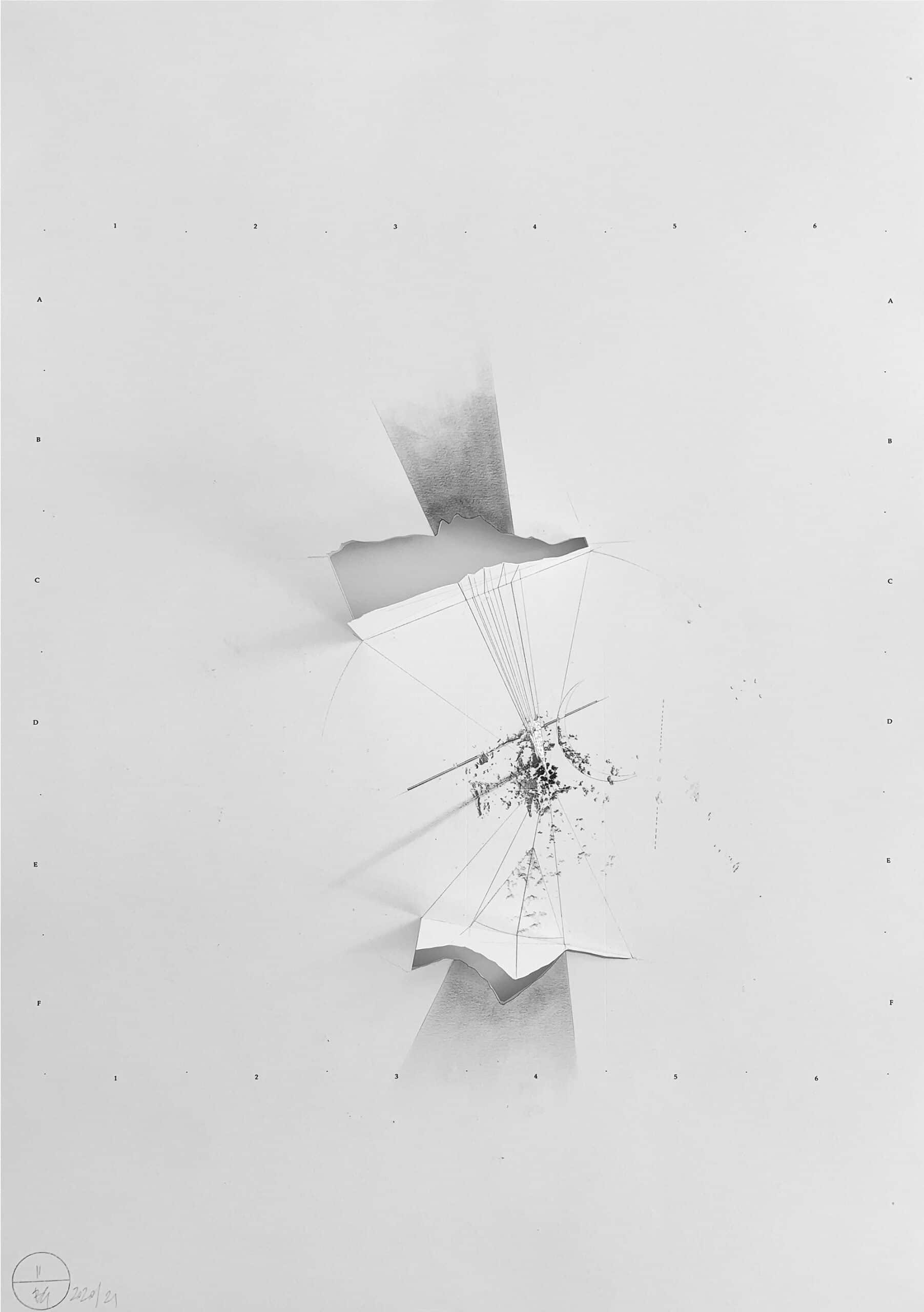

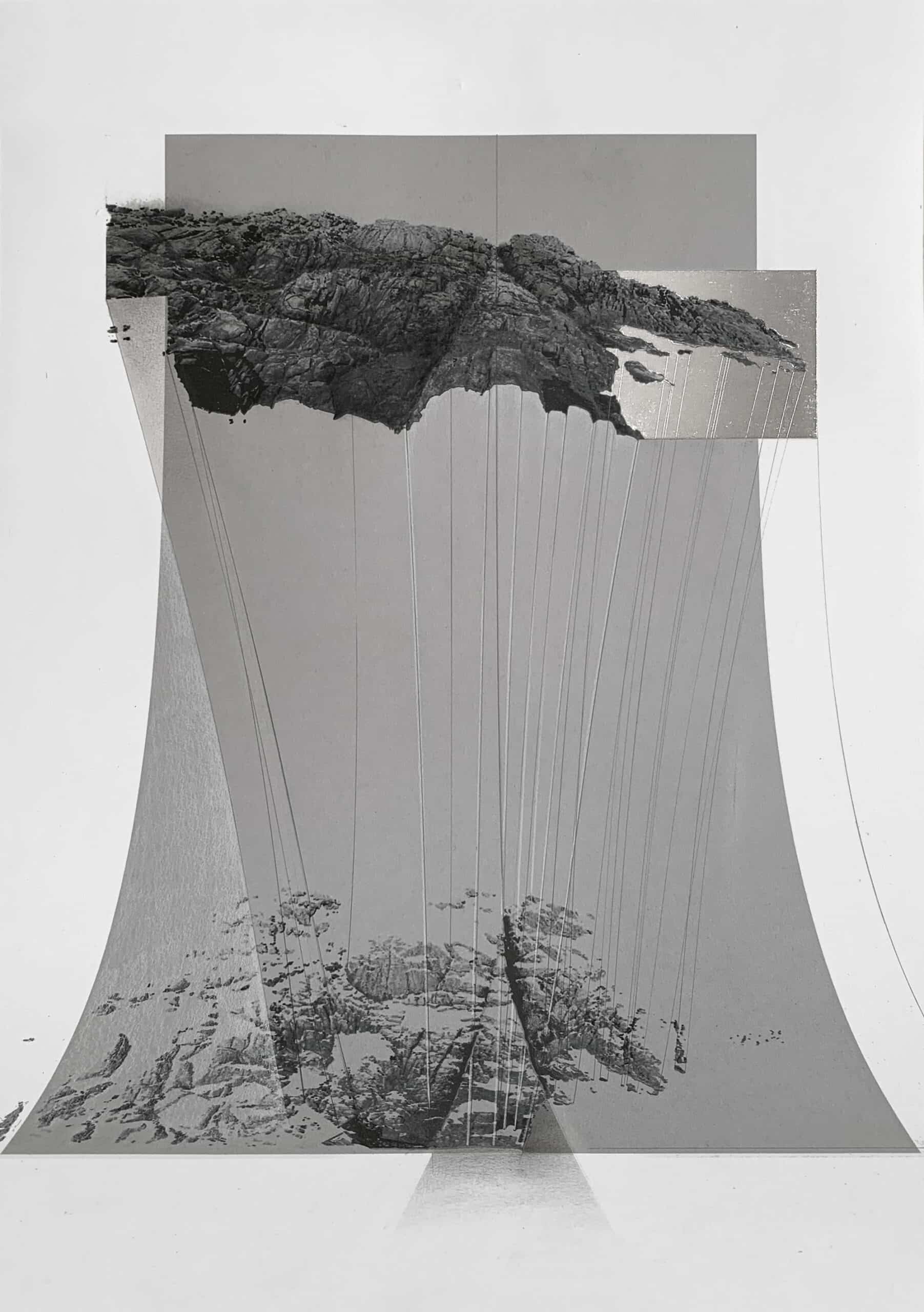

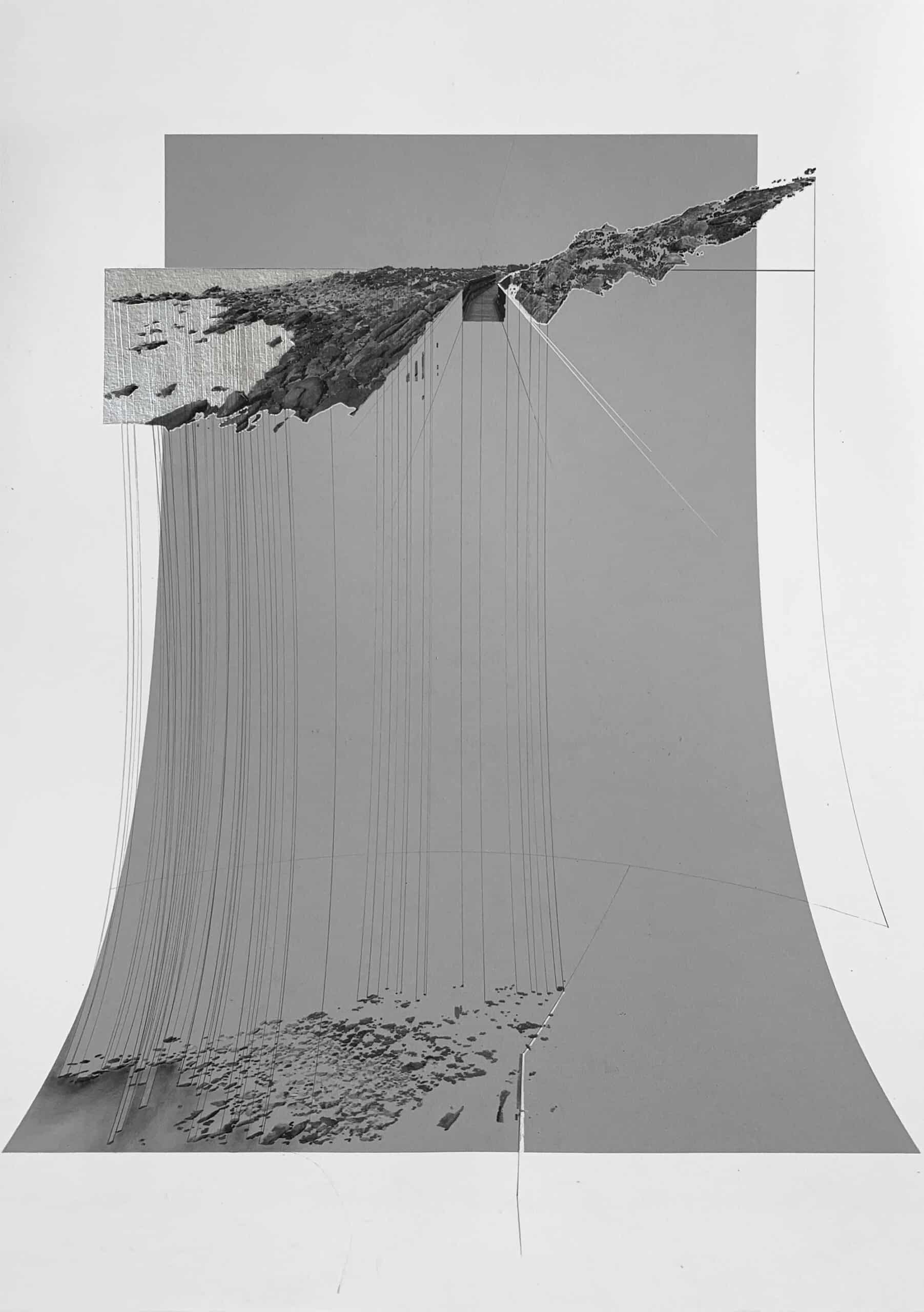

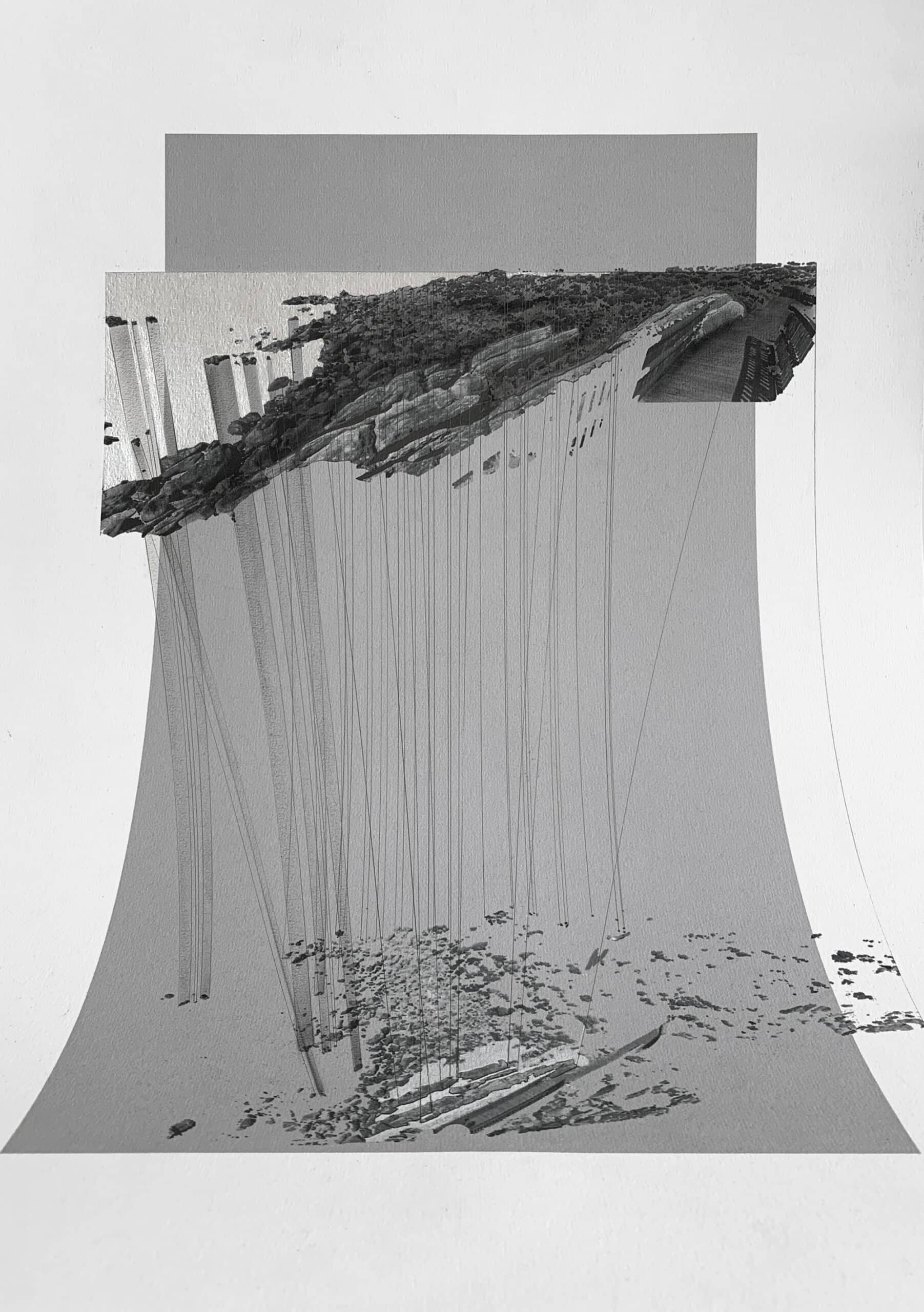

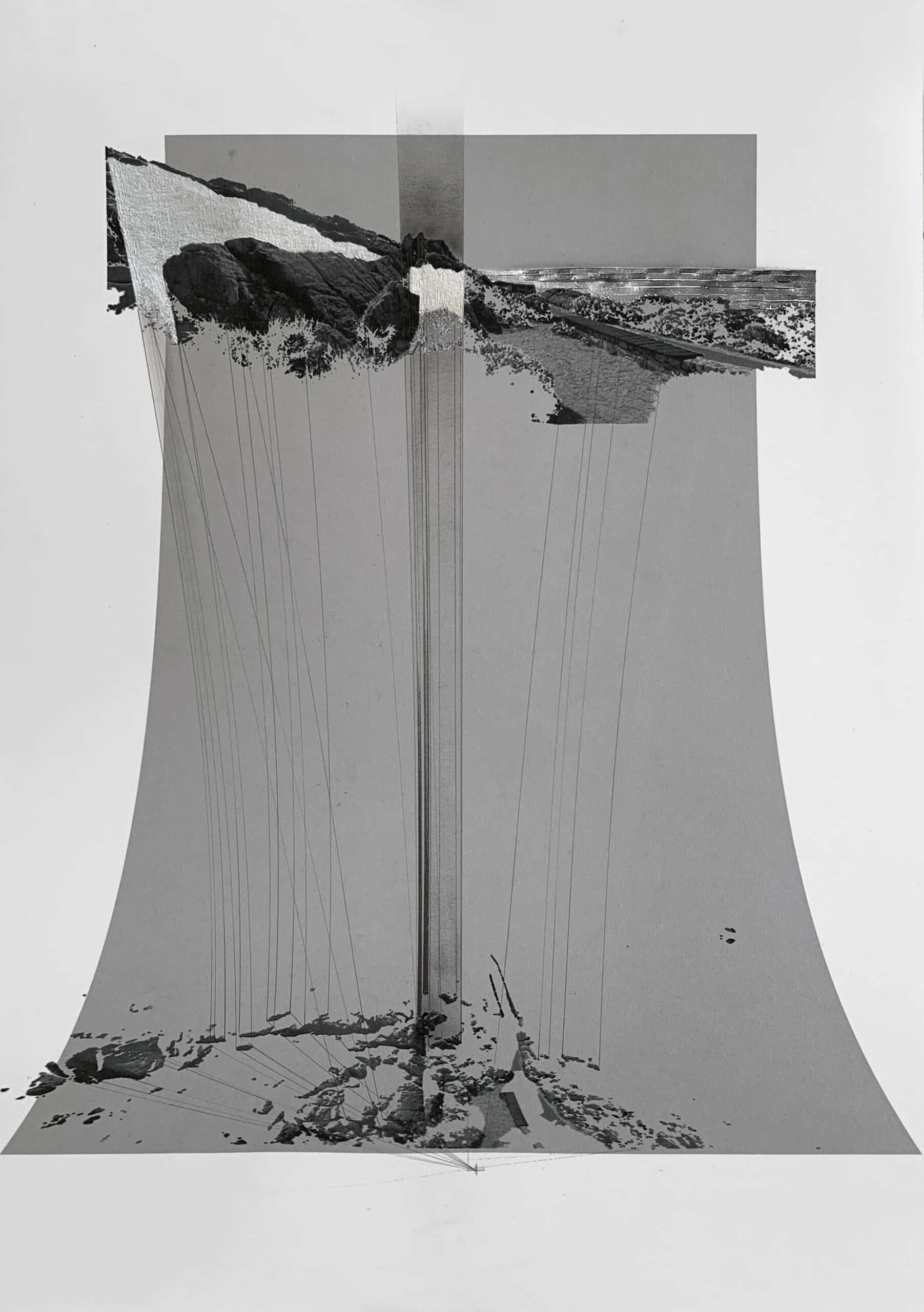

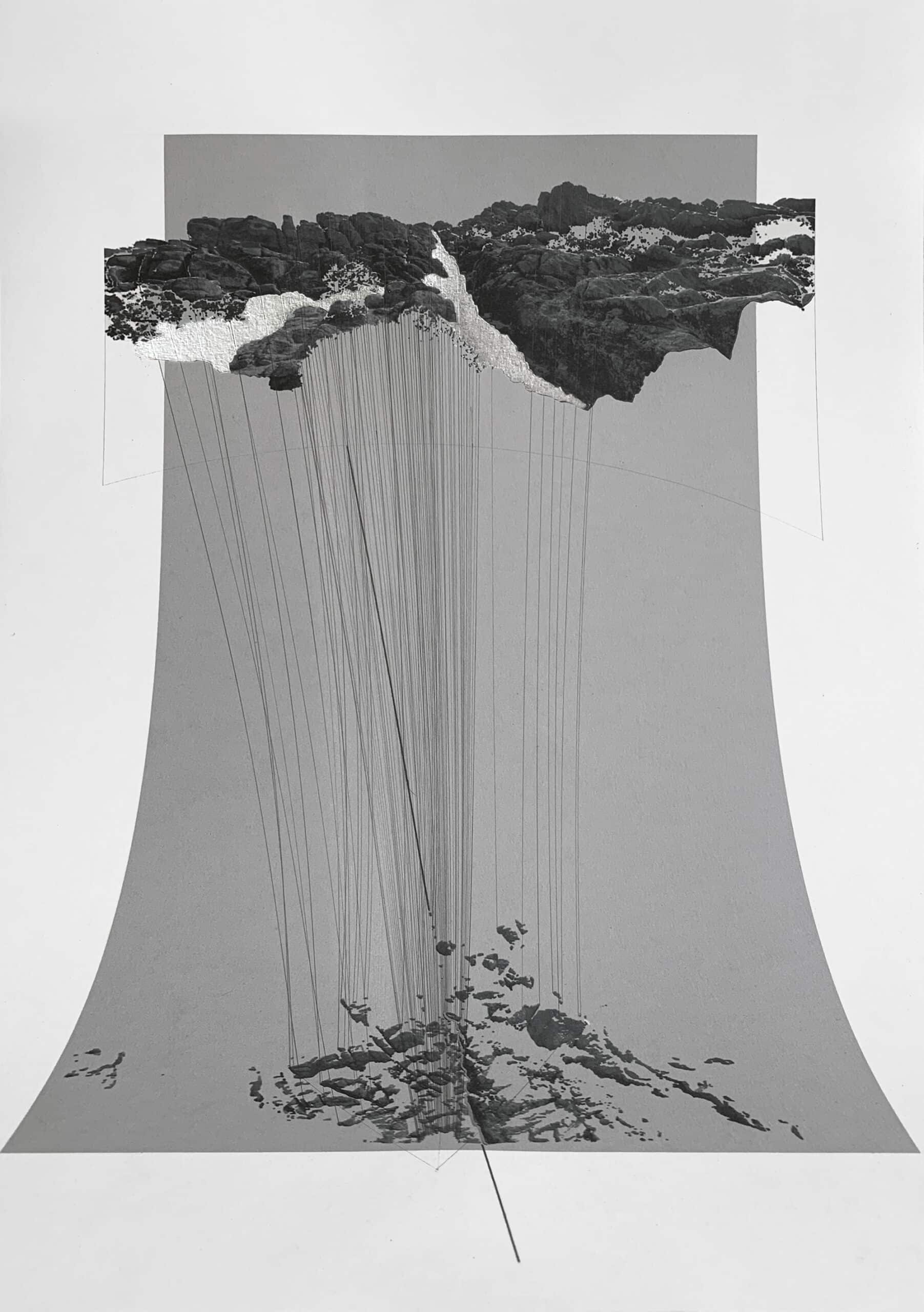

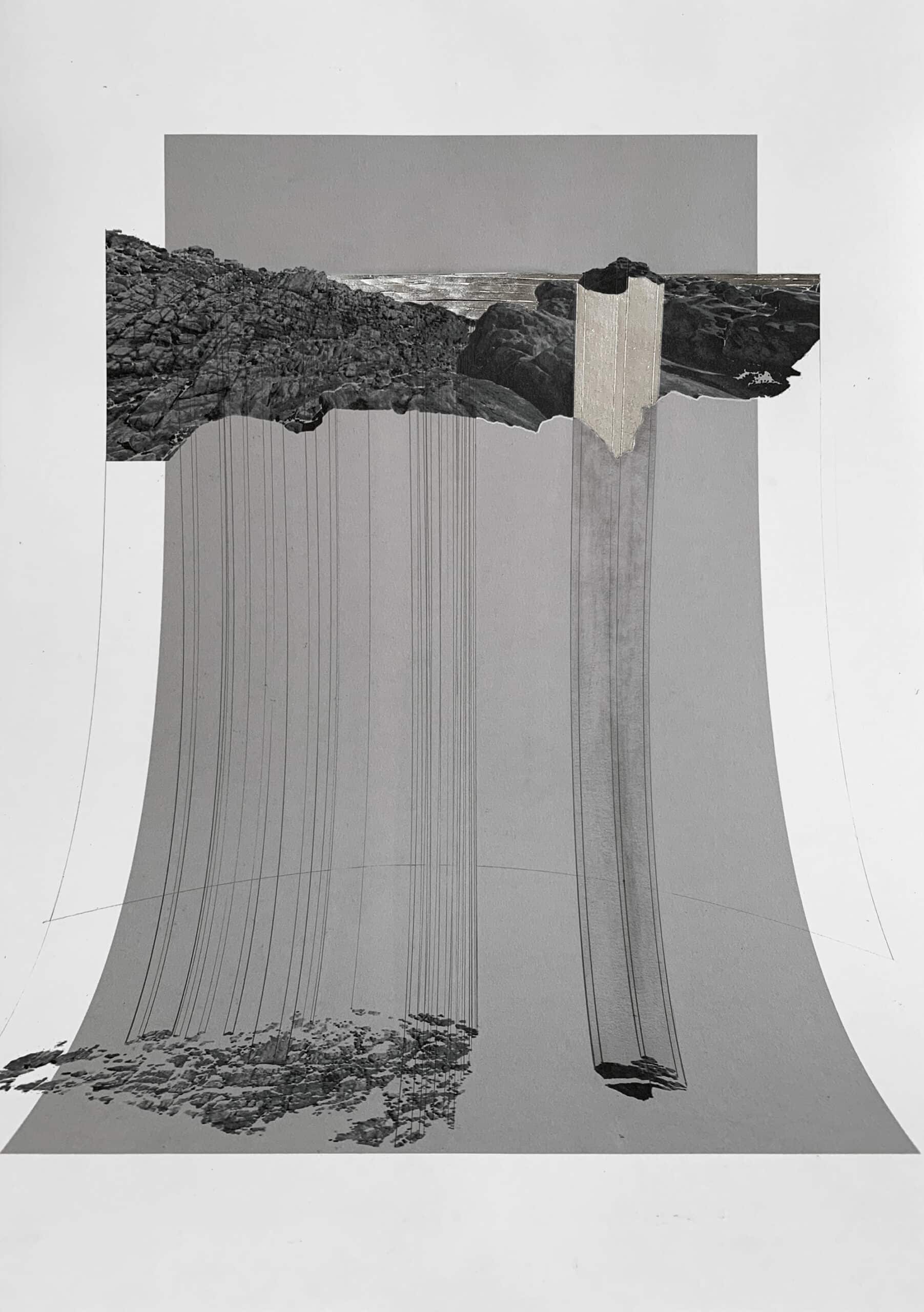

Having flattened the data through plan analysis and then revisited its three-dimensionality, I wanted to stretch the page to describe the myths I had now drawn from its geography. And so the paper folds up sometimes, and down others, cones of vision and limits of view are articulated, features are brought out, geometries articulated, and relationships formed. There are three maps that contain pairings, where the camera is placed between two physically opposite but formally resonant conditions (peak to peak, fragments to fragments, canal to canal). In these, the paper is folded up to create actual three-dimensionality. On others, orthographic extrusion, projected shadow, and small cuttings and bendings lend depth. Lines sometimes connect perspectival information to camera location, explicating the relationship between plan and perspective. Mapping 03: Dissolving, uses anamorphic projection that snaps the panoramic pop-ups into connection with the camera point. The maps and their names tell stories. The water remains absent.

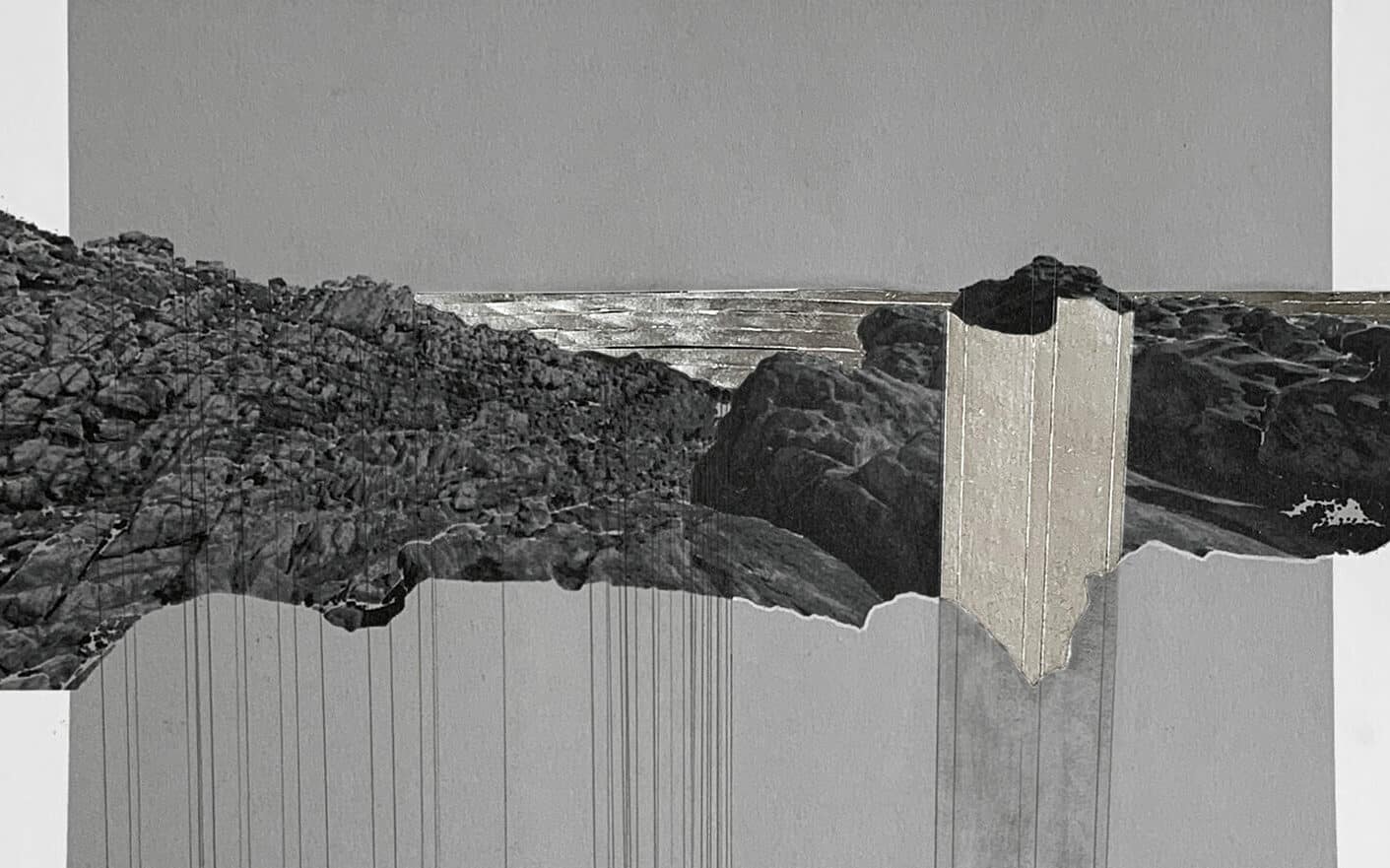

The Scan set shows you something that can be seen in perspective from each location, twice. First, top of page, in perspective (as per the umwelt of the scanner), and second, below, from 40 metres above. This is a nonsensical view, one that shows up all of the gaps between the features that the camera perceives. A series of lines connect the two instances of points and objects, showing them pulling apart. These carry their own myths and names — Fault, Two Terrains — and pick up the same characters that emerged in the mappings — Peak, Tower. These were exhibited curved, with the perspectives (at eye level) bending into plan (below and tilted toward horizontal). Graphite and charcoal create blackness, but the graphite from another angle reflects light. This luminosity, the silvering of the page, lends a sense of value through a material that is not in itself valuable. The sea is allowed to appear in this set but only through reflection, and sometimes abstracted ripples — cut into the page and bent.

I managed to get home for the exhibition and travelled to Canal Rocks with Leonie and Pete, who created the scan. After all my myth-making and longing for home, I found the Tower to be a rock no taller than my chest.

Beth George is currently working on a body of drawings and models for Covid Retrospect, an exhibition curated by the Architecture Et Cetera Lab.

This text was submitted to the General Autograph category of the Drawing Matter Writing Prize 2021.

Notes

1. John Berger, And our faces, my heart, brief as photos (London: Bloomsbury, 2005), p.26.

2. Manuel de Solà-Morales, ‘The Culture of Description,’ Perspecta, vol. 25 (1989), p.18.

3. Ibid., p.18.

4. For more on umwelten as perceptual life-worlds, see Jakob von Uexsküll, A Foray into the Worlds of Animals and Humans, with a Theory of Meaning, trans. by Joseph D. O’Neil (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2010), p. 43.

5. The Bellman’s Map I first saw was published in ‘Water-Land/Tierra-Agua’, Quaderns D’Arquitectura i Urbanisme, vol. 212 (1996).

Base data for the drawings was point cloud scans created by SpatialCo.

– Sebastiano Brandolini