‘I chose a distant meadow’: The House that Neutra Built

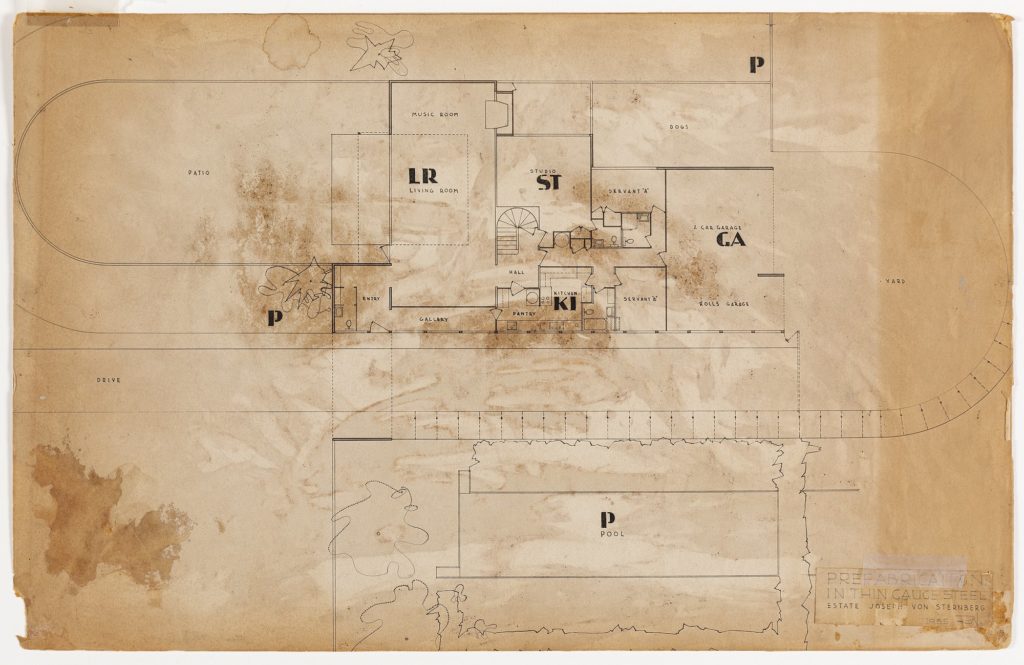

There are several curiosities in the plan of this classic modernist house by Richard Neutra. First, more area is allowed for dogs than for music. Second, there is a two-car garage, but a separate parking-space for a Rolls-Royce. Here is fine discrimination.

But fine discrimination is exactly what you would expect from a client who, like Erich von Stroheim, acquired a nobiliary particle as social promotion.

This client was the man who became Hollywood’s Josef von Sternberg. In 1934 he commissioned Neutra to design a house at 1000 Tampa Avenue, Northridge, in the San Fernando Valley northwest of Los Angeles. It was built the following year as von Sternberg was transitioning from Paramount to Columbia.

It was Neutra’s habit to quiz his clients about their preferences with unusual thoroughness and this resulted in another curiosity not evident on the plan. Von Sternberg insisted that the bathrooms have no locks. This in order to deter suicides by neurotic guests. As the patron of Marlene Dietrich who starred in von Sternberg’s The Blue Angel, he knew a thing or two about temperamental actress-types.

The house was characterised by huge, generous swooping metal-clad curves without and well-ordered rectilinear spaces within. A ship’s searchlight was featured over the porte-cochere, a gesture typical of the machine romanticism of the day when Herbert Read offered a ship’s propeller as art.

In his autobiography, Neutra makes fun of an anonymised client who insisted on an electrified moat. The Sternberg house does not actually have a moat, but it does have a water-feature which could be mistaken for one. Isamu Noguchi designed a swimming-pool that was not built.

Von Sternberg had left his Orthodox Jewish home in Vienna in the silent movie period, but his culture wandered with him westwards because the California where he settled had become the new focus of German-speaking culture. Within greater Los Angeles his neighbours included: Thomas Mann, Alfred Doblin, Alma Mahler-Werfel, Bruno Walter, Theodor Adorno, Fritz Lang, Billy Wilder, Rudolph Schindler and, of course, Neutra himself.

But having escaped from the Vienna ghetto, von Sternberg also wanted to distance himself from so claustrophobic, if distinguished, a community. Of his site he said with an unexpected pastoral touch: ‘I chose a distant meadow.’ And what Neutra designed for him was no less than a moated retreat where he could enjoy his collection of High Modernist art – including Kandinsky, Archipenko and Matisse – along with his dogs and, of course, his Rolls-Royce. Presumably, the searchlight was specified as a defence against intruders like Thomas Mann from the Wild West of Santa Monica.

It’s a nice warning against too prescriptive a view of history that in the year von Sternberg commissioned Neutra, in London Sir Reginald Blomfield published his potty anti-modernist rant Modernismus. To Blomfield, the style so adroitly commodified for rich Californians by Neutra was evidence of nothing less than Kunstbolschewismus. It was an architecture of cosmopolitan, elitist, Jewish Communists.

So what a pleasant irony that in 1940 von Sternberg sold the house to Alysa Rosenbaum who, re-branded as Ayn Rand, published The Fountainhead in 1943. Besides its lionisation of the architect-as-consummate-genius, Rand also railed against Bolshevism. She found the house ‘unbelievably wonderful’ and Julius Shulman took glorious photographs of her living there in 1947.

It is often assumed that Howard Roark, Rand’s architect-hero, was modelled on Frank Lloyd Wright, but Neutra was fond of suggesting he was the source…at least insofar as Roark’s priapic tendencies were concerned.

The von Sternberg house was demolished in 1972 and replaced by a condo. This drawing, along with Shulman’s photographs, is all that remains of a uniquely beautiful building.