Notes on the Visionary Spaces Exhibition at the Belvedere 21

I arrive at the Belvedere 21 after visiting Walter Pichler’s famous farmhouse in Sankt Martin an der Raab, only a few days prior—it is a stiflingly hot day in Vienna and for some reason, I have chosen to walk. I arrive at the Belvedere 21 to attend the Visionary Spaces exhibition that showcases some of Walter Pichler’s works in concert with Frederick Kiesler’s.

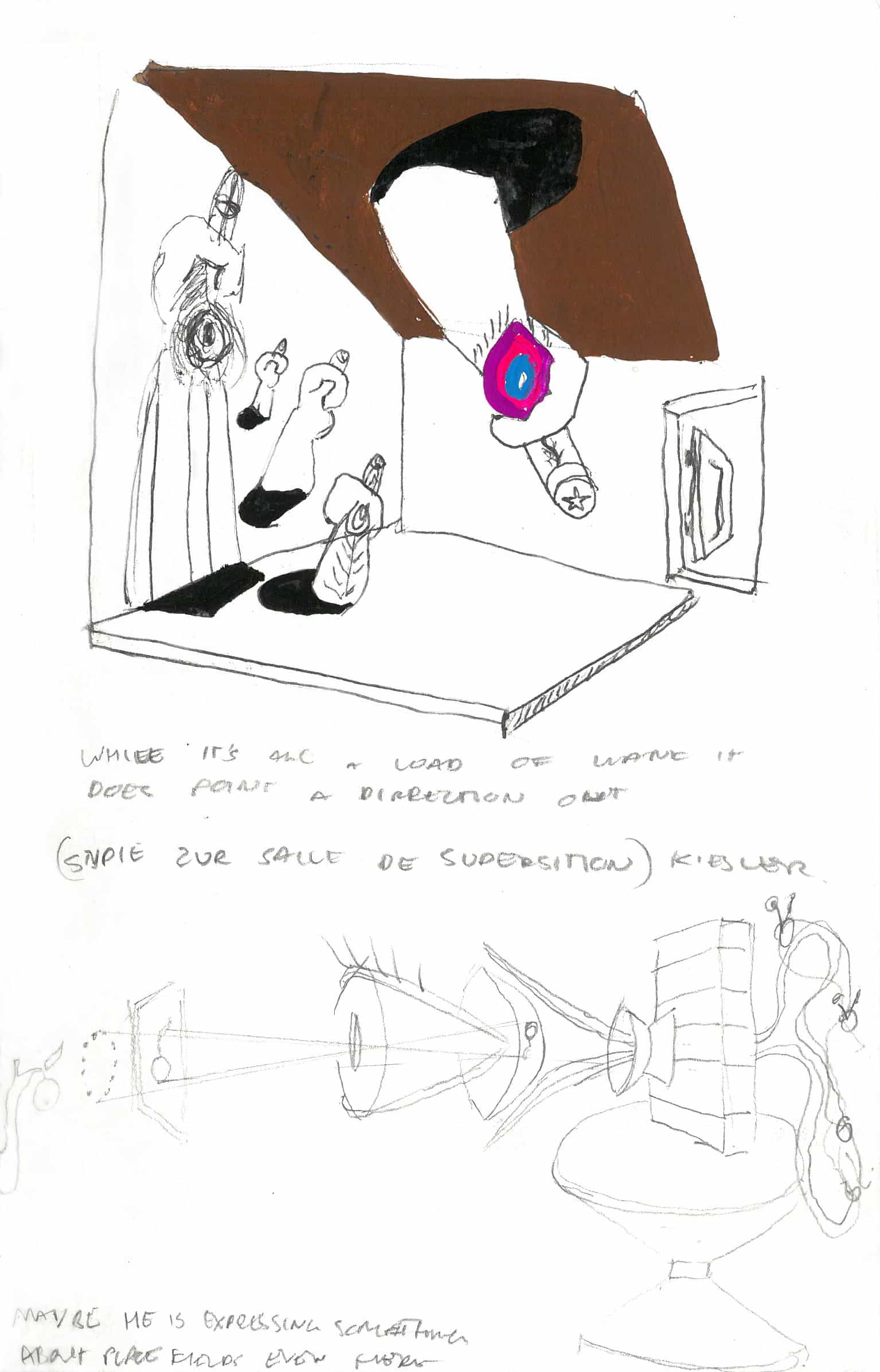

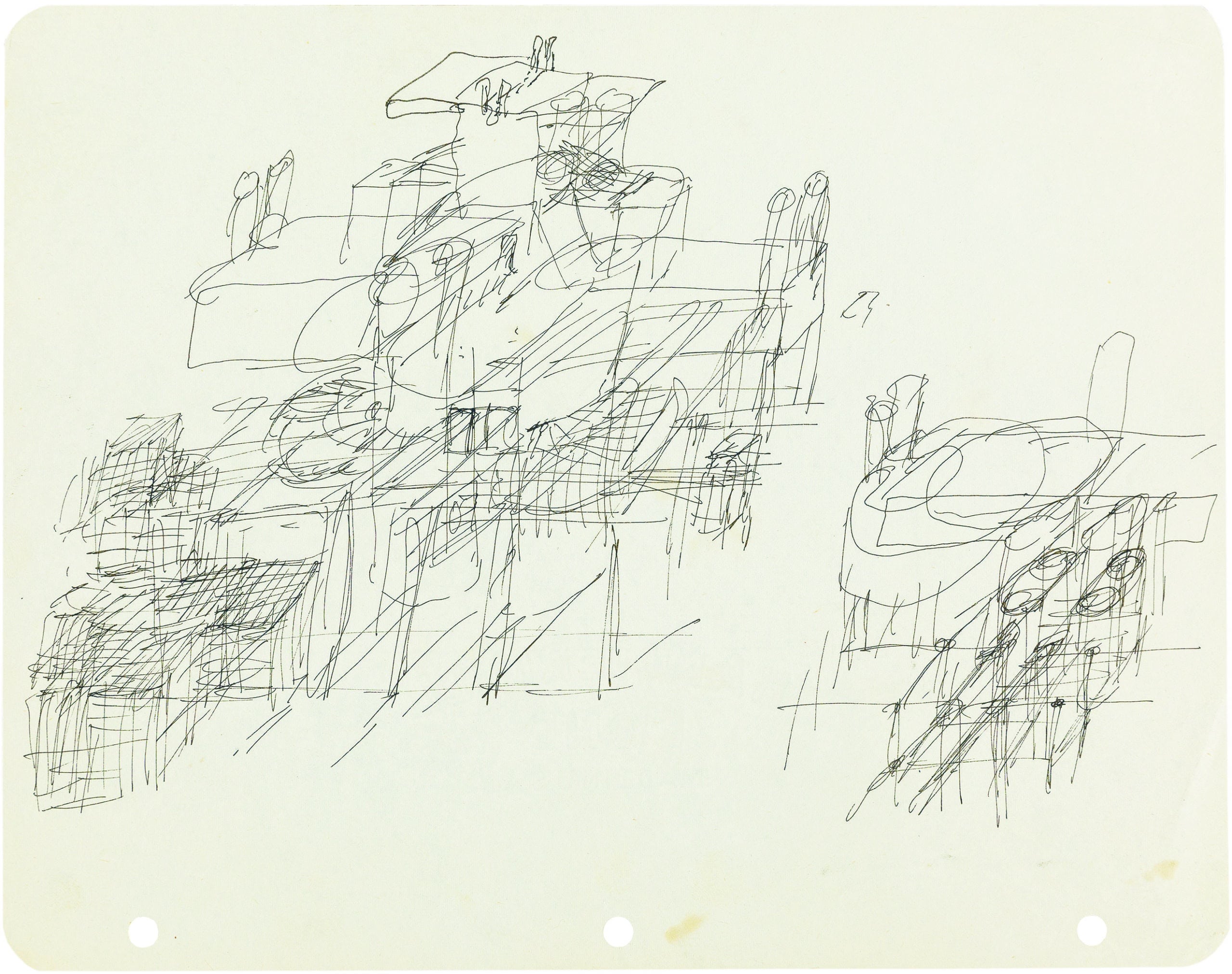

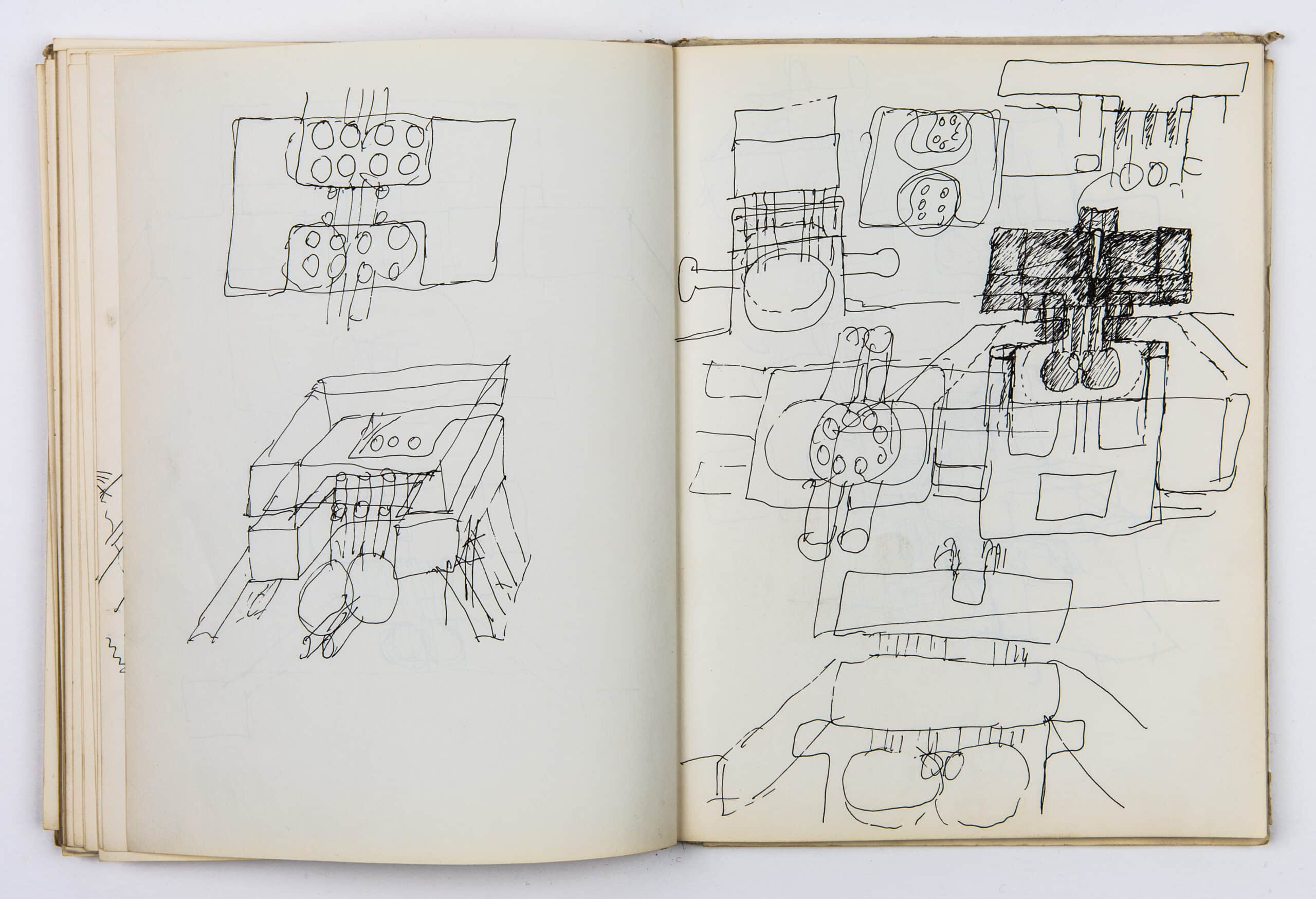

After walking over the concrete entry bridge, admiring the floating box and the maroon external steel structure of Karl Schwanzer’s Austrian Pavilion, which was converted into the art gallery after the 1958 World’s Fair in Brussels, I enter the Belvedere 21. Seeing the two bodies of work presented side by side, I cannot help but first make a comparative analysis. I walk around the gallery relatively fast and take note of my first impressions so that I can then slowly go around afterwards to each of the works, give them the attention they deserve, and read each of the descriptions. I write in my Moleskine a singular statement: ‘Fredrich Kiesler reads as an unskilled tripper when presented next to the refined craftsmanship and maturing ritualised practices of Walter Pichler.’ The first comparison that irks me is the curation of Kiesler’s Study for a Vision Machine next to Pichler’s Prototypes. Kiesler’s drawings diagram the two sides of the boundary between body and world—in a manner that would align with the aesthetic preferences of someone watching Adventure Time while tripping. Pichler’s Prototypes, on the other hand, critique, play with, and use as design provocation the alterations to our spatial experience, that Pichler had been witnessing as a result of new technologies. ‘I guess, one could say, they are BOTH reflections on new technologies’ I think to myself but resist the urge to write down—while also resisting the curator’s guidance.

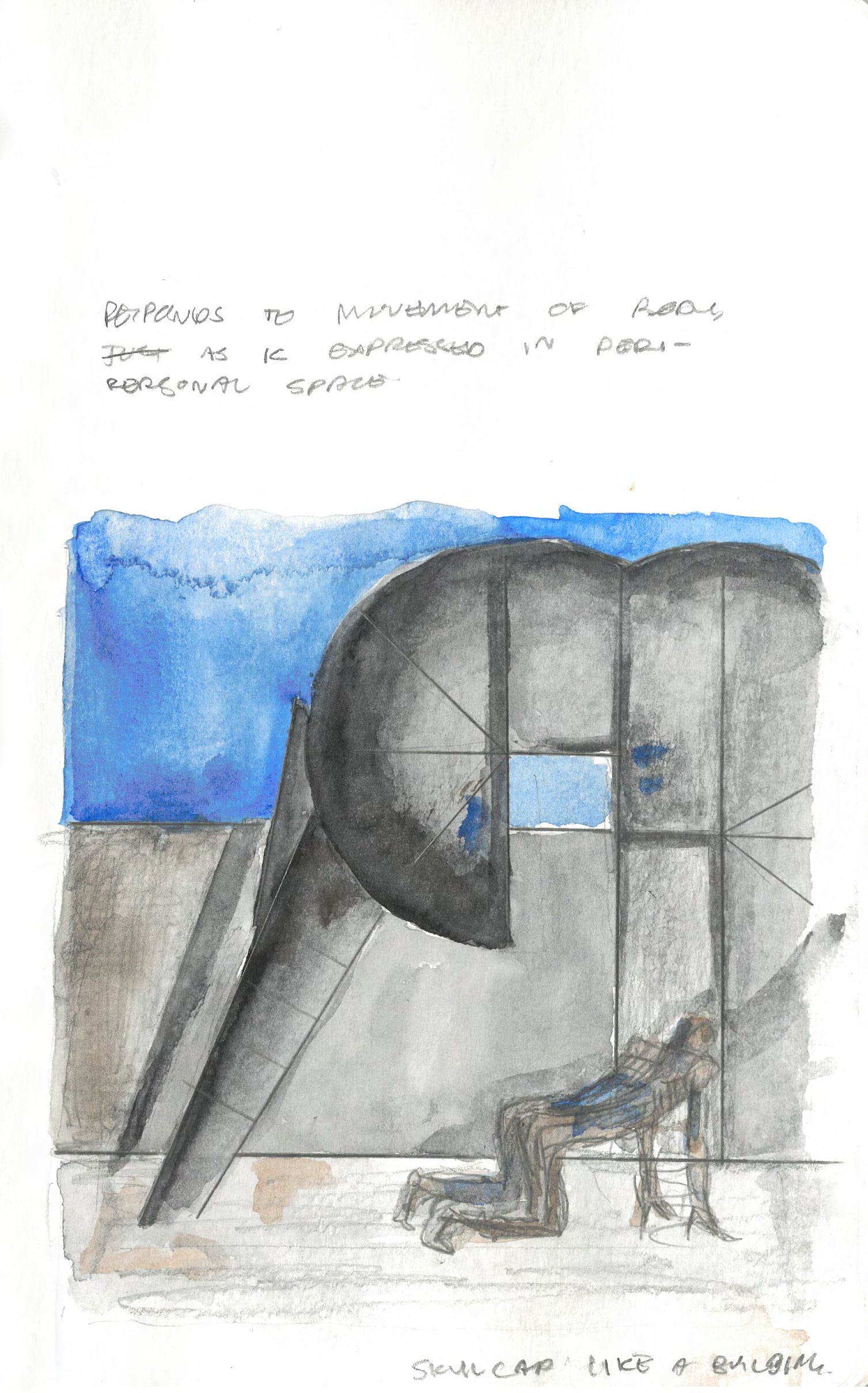

On the flip side of the curved wall, that makes the exhibition into a ‘Display’—a trend that seems to be in fashion in European curation at the moment—are models of Pichler’s Skullcap (Like a Building) and a collection of his other Skullcaps, opposite Kiesler’s Bone II. Again, the inferred duo irritates me! Pichler tests and displays varied media, as he gradually figures out how to build a space that mirrors the experience of an I, reenacting the internal scale shift that occurs when transfixed by one-pointed attention, or when disassociating from an experience entirely. Kiesler, on the other hand, merely mounts a brass dildo on top of some crafted-together stones and sticks that seem to be expressing that he is experimenting with Freudian psychoanalytics. Maybe Kiesler is expertly expressing something of the pastiche of clichés that scaffolds his own psyche and experiential history. Even if he is, yet again, his work appears descriptive rather than expressive or affective, and while I am not, at all, averse to immature art, it leaves me hoping that I no longer have to compare such vastly different artworks.

The main narrative unfolds around one chance meeting, where (potentially) the pair discussed their shared interests, or (potentially) Pichler was irrevocably changed by the insights of an older practitioner. Either way, the connection between the two practitioners seems to be representing a more contemporary agenda, aligning itself with a trend that is occurring now. A trend that inspires us to free ourselves from the constraints of contemporary architectural practice, either by blurring the lines between architecture, sculpture, and furniture design, or between architecture, urban design and landscape. Both avenues seem to promote the desire to release ourselves from the office job we accidentally found ourselves in when pursuing a career in the building or creative industries—I admit I envy the times that these practitioners worked within.

As I re-enter the gallery, the curation guides me to the left where I am presented with a very long text describing the story of the pair meeting (that I do not want to read) as I see Kiesler’s famous Correalist Rocker and Instrument out of the corner of my eye—these fill my belly with excitement. This first section of the gallery pairs these pieces with his Nesting Table and Standing Lamp, leading to Pichler’s Galaxy 1 and 2 and then his Prototypes, all under the thematic ‘Functional.’ The undulating spirited form of Kiesler’s chairs is so imprinted in my mind that I can do nothing but gaze at them with that sort of admiration you have for objects that seem familiar because you have praised them for far too long. They look precisely like his drawings of them. They are beautifully crafted and playful and invite both animation and action. Likewise, his table and lamp are chunky and wiggly and in the context of the gallery, and next to Pichler’s work, appear to have been made of, or themselves defined the aesthetic of their time. Photos of this or that celebrity sitting in the chair hang along the wall—highlighting the fashionable nature of his work and making him seem more like the cool tripper who hung out with all the celebrities, making funky stuff with all their money—an enviable route to freeing yourself from the monotony of a desk job, for sure.

Next to these works Pichler’s Galaxy 1 and 2 seem simultaneously pragmatic and futuristic and don’t hold any of the lush material knowledge that is endemic to his later work. Moreso, they do not seem to house any of the vitality or essence of his later works—they seem like a product, rather than the creations I have come to expect from him. I guess this is what the curator means by ‘Functional.’ As products, they draw from the aesthetics of space travel, in a way that contributed to the aesthetic of a generation, but I see very little of him in them and am utterly unmoved. I find myself barely capable of contemplating the work at all and am much more inspired to move on to his Prototypes.

Pichler’s Large Room Prototype 3 dominates the back corner of the room. The curtains of the gallery are open, and so the tall walls of glass (and the world beyond) create a perfect backdrop, illuminating the huge inflatable sphere with the metal box in the centre and the leaf blower at the rear. I have seen photos of this work before (and crafted similar inflatable structures myself), but in this context, I see this piece as a ‘real’ prototype. It appears, to me, as a seed that fuels both his extensive, future material exploration and mastery, and an exploration, or sort of sculptural diagramming, of spatial experience that eventually leads him to a mastery in affective architecture. In my mind, this piece is the first in the show that is ontologically concerned, and yet again, as soon as I see it, the previous works suddenly seem mundane. With this work, he begins to use sculpture as a practice to question the very nature of being—rather than simply designing fashionable objects.

Next to it are Pichler’s Small Room Prototype 4, Finger Stretcher, and Radio Vest, which appear almost prophetic—as I photograph them with my iPhone and blast Ludovico Einaudi from my ear pods in the silent gallery. The Small Room Prototype 4 is a helmet-like structure that fits over the head with a built-in television. While larger, it acts in the same way as virtual reality headsets do—detaching the visual from the felt world outside. The Radio Vest pairs objects and shop drawings, whereas the Finger Stretcher acts as a tool—extending the space that is attended to as bodily into the object. All act to edit our experience and extend or alter what it is to be within a perceived world.

As mentioned, these works are paired with Kiesler’s Study for a Vision Machine and Study of the Salle de Superstition. This time, I read the curator’s text. The curator suggests that both sets of works emerged from a deep interest in perception. It seems a vast jump to suggest that Kiesler is depicting any sort of genuine knowledge of visual perception, or any pursuit thereof, especially as he diagrams the boundary between body and world as a brick wall. Pichler, on the other hand, is not explaining anything, he is using the practice of sculpture to imagine, to interrogate and to express a deeper understanding of not just vision but of spatial perception. Moreover, in these works, spatial perception starts to become his medium, as he designs devices for altering and editing perceptual experience itself.

Around the corner, a stunning brass surface is poured onto a mound of sand, glinting in the light that is streaming in through the glass walls that edge three of the four facades of the gallery. This creates an unfortunate amount of glare on the other works, but perfectly plays off the vein-like diverts of Pichler’s Two Crucibles with Inflows, emphasising the jump to an expert material and tectonic understanding. Next to it is a table designed (and quite clearly not made) by Kiesler. It is The Marriage of Heaven and Earth, obviously designed without any expressive understanding of brass casting techniques or the inherent semiotic qualities of the media. This table, made of heavy quantities of brass, may as well have been sticky taped together, as the comparison in craftsmanship is astounding and leaves Kiesler looking like a kid at daycare—it makes me think about how wasteful brass construction is and about how, morally, you couldn’t justify such a work today.

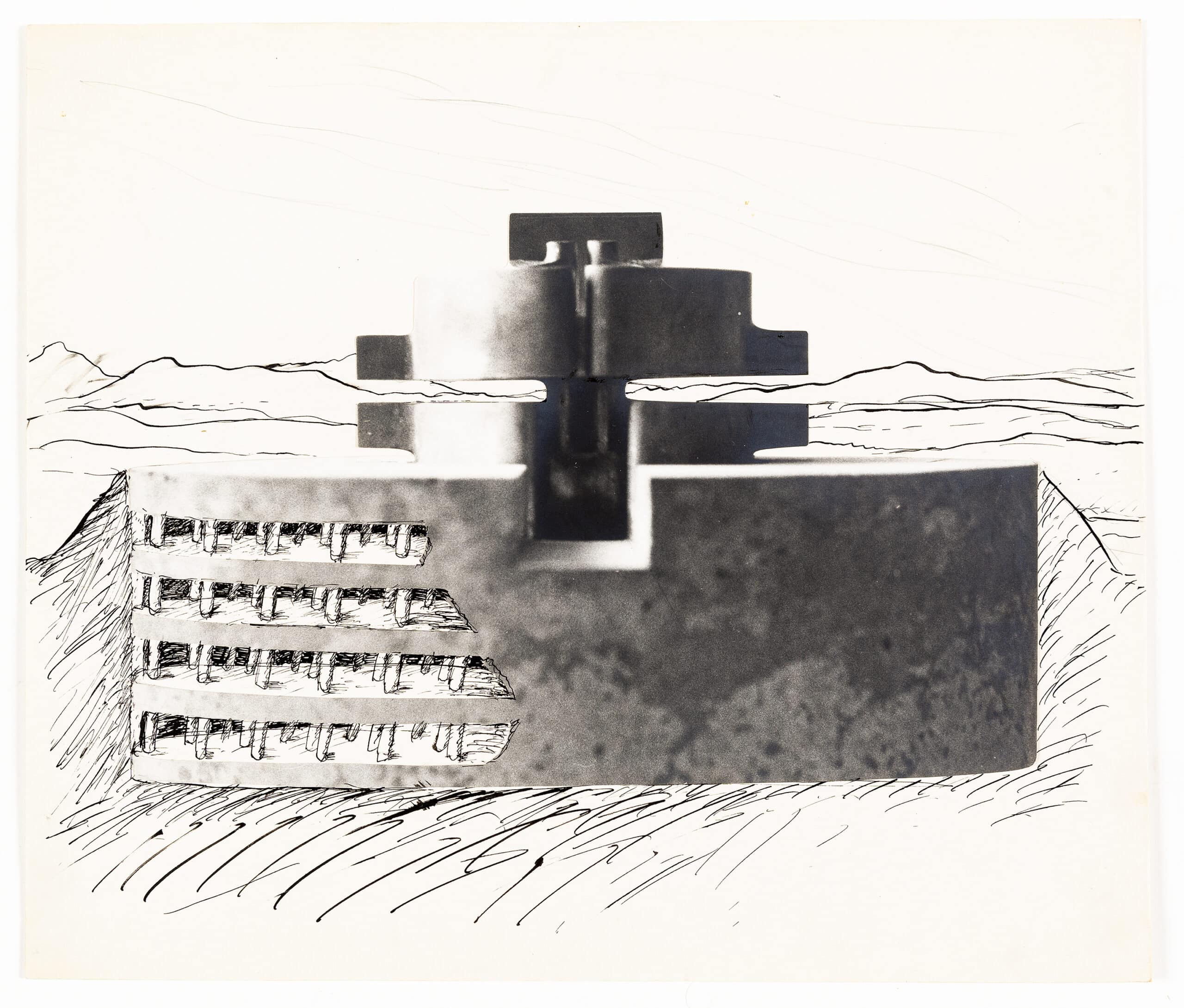

From here, I saunter back to where Kiesler’s Endless House sits in an adjoining space to Pichler’s drawings and models of his Underground City, and Underground Building, and the abundant collection of his other sculptural work, including his Portable Shrine, Old Figure, Butterfly, Chapel—along with a set of other architectural works that could have been a whole different exhibition. Before moving into this ‘second exhibition’, I finally see Kiesler’s genius, and the two figures suddenly seem to be on par. With this work, Kiesler’s countless trips, and wasteful play in different mediums, seem to have finally led him to a metaphysical or ontological endeavour that is quite remarkable. With this project, Kiesler is blurring the boundary between architecture and sculpture to free the practice from the international modern and to move toward crafting more sculptural forms. In this way, he could be regarded as a sort of forefather of many later works that similarly play with form. OR his work could be tied, as the curation suggests, to Pichler’s, with as perfunctory a comparison as ‘Organic.’

The more remarkable aspect of this work reveals itself through his drawings. The organic form molds to the contours of Kiesler’s thoughts, as he grapples with the complex relationship between procedural memory and spatial perception—with a somewhat similar perceptual and conceptual framework to Shusaku Arakawa’s and Madeline Gins’ in their Reversible Destiny Lofts. In this project, the pair examines ‘the architectural body’ of our immediate-perceptual-surround and attempts to create apartments for living forever. It is only at this moment, that I can see Kiesler using, as Pichler did with the Prototypes, architectural practice as the methodology for the pursuit of knowledge. He plays with curved and undulating forms and once again makes models in media, that he is clearly not intimate with, but this time this doesn’t matter. In his drawings he focuses on diagramming spatial movement and intuiting, through practice, the relationship between memory and action in intimate or daily spaces and routines—establishing a ‘process architecture’ as the exhibition catalogue refers to it. With the practice of drawing, he seems to have heightened his spatial and temporal perception, so that he may pursue expression for the looping of perceptual memories, that activate our sense of agency and of being in a world—revealing, as with Pichler’s mastery of varied media, a profoundly deep understanding of spatial perception. Imagining through the undulating spaces of his Endless House, I am overjoyed to see that he has (finally) found his media and a more rigorous practice.

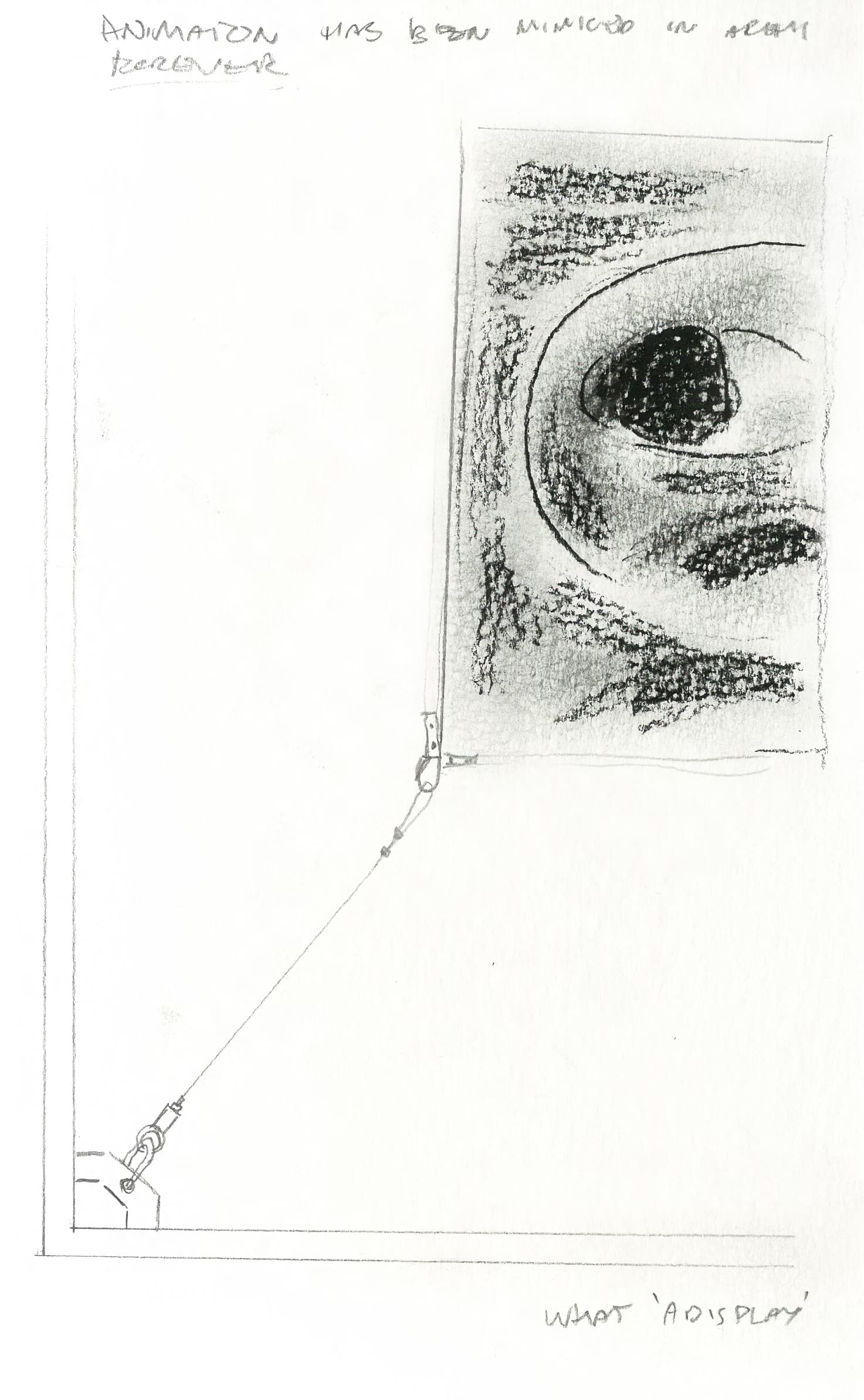

As I move around the ‘Display’—made of elegantly welded together partitions with slender wiring and fastenings that hold the work suspended in space—to Pichler’s other projects, I become abundantly aware that Pichler is an authentic sculptor and craftsman, who has added architecture to his extensive collection of mediums. This is not so much an act of blurring the boundaries between two professions, as it is an extended and matured sculptural practice. While each project is formally and politically interesting, what strikes me, looking at the collection of drawings and models on display, is his process for testing and thinking through his varied collection of media. He makes with MDF and plaster, and then with brass or lead and concrete, and then with straw and found materials; he performs rituals of vitality, he draws, he draws again—each time testing and changing and carving out the final form. Through each act, he slowly births something new into the world, that accretes all his experiential understanding into a singular object.

With the whole collection in mind, I realise it is through this process that Pichler’s works become so affective, and are in themselves a rigorous pursuit of experiential understanding and imagination. With each piece, he seems to select a puzzling experience to understand and then explores it through each media or media relation, repeating it across varied scales of consideration—scales that are both spatial and temporal, or procedural. Through each media test, he uncovers and layers something about the material quality of existence into the project, through each scale shift he layers something of his own being into the world. With each act, the piece gains more reality and finally appears as an elaborate expression of a profoundly deep experiential understanding —leaving the viewer moved into questioning their own experience.

As a comparison, the more purely architectural works of Frederick Kiesler seem underdeveloped, and flat. Comparing the two, in the gallery setting of the Belvedere 21, sets up an unfair comparison. Becoming aware of the curator’s intent—to identify that the two practices of art and architecture, have constantly been blurred—I would say that unfortunately it rather highlights their distinction. Pichler is a sculptor who has added architecture into his extensive collection of mediums, and Kiesler is an architect and furniture designer, who was overly awarded by his celebrity friends for having some crafternoons with his tripper buddies, who happened to have an overabundance of brass. Their professional distinction lies not in what scale of project they work on, or in what mediums they make in, or in the organic nature of their forms, but in their different methodologies for thinking through complex ideas. Pichler tests and explores through his media, where Kiesler (aside from the Endless House) develops a conceptual understanding through whatever ‘research’ he deems fit and then applies a design process to produce an output—leaving the making to another.

By commenting on this distinction, I do not look to undo anyone’s work in attempting to blur the boundaries between sculpture and architecture or to undermine it. On the contrary, I am in full support. However, the exhibition seems to highlight that if we are to further pursue such blurring of disciplines, the pursuit might not simply be about scale or the programmatic and performative brief but might rather be about one practice informing a regeneration of the other. Positioning Pichler and Kiesler as the forefathers of such a movement is not only apt but applaudable. Regardless of any comparison or distinction between the two, the exhibition makes me feel that anyone wasting their life away at a desk or computer—as I am now—should get out and engage with the ‘dirty real’, by making some things, so that one day we might get on with contemplating the nature of being and the potential future of the profession. And in that regard, I consider the exhibition a raging success.

In Drawing: The Enactive Evolution of the Practitioner (2010), Patricia Cain develops a practice of enactive copying—whereby she methodically enacts the process of another artist’s drawing practice and, while doing so, questions how we think when we draw. She then uses this method to reposition drawing as a tool for retraining the eye to see the world anew. Architects, as opposed to artists, produce drawings for many different reasons—some drawings are sketchy expressions of a vision, some are thinking drawings, and others are presentation or construction drawings. Each type requires a different kind of thinking and communication. By enacting a similar process to Cain’s while attending to architectural drawings here, I do not simply question how we think when we draw but use the process to put myself in the other architect’s hand and imagine the world that they are scribbling out as well as the lived experience that they are drawing from. I question why the drawing was made at all and what the author learnt from its production. It becomes a sort of séance.

Emerald Wise is a creative practitioner, academic, and educator, whose work revolves around ways of looking at the world and embodied processes for enacting knowledge. She co-founded the emerging creative research collaborative UNMAKE studio and the architectural practice Whispering Smith, which she left in 2018. She is currently a PhD Candidate at the University of Newcastle.

On the 22nd November 2024, the exhibition Visionary Spaces. Walter Pichler Meets Frederick Kiesler in a Display by raumlaborberlin opened at the Kaiser Wilhelm Museum.