Parataxis

‘Whatever elements that may come to hand or that are selected from the profusion of materials within reach, are combined with words to create a simple poetic image. This should amuse, disturb, mystify or provoke reflection. These images above all should entertain – the only sure road to appreciation.’

Man Ray, ‘Objects of My Affection’ in Oggetti d’affezione (Turin, 1970) p. 5.

From either direction you arrive from a turn-off from tarmac road to a lane that slopes down towards a scattered settlement of buildings sat on roughly-cast concrete. Oversailed by a profile fibre cement roof and held behind the remaining walls of an old barn was the archive. Walking across concrete cattle slats laid between a gap in the wall, I stopped, opened the door, and stepped up into the room. [1]

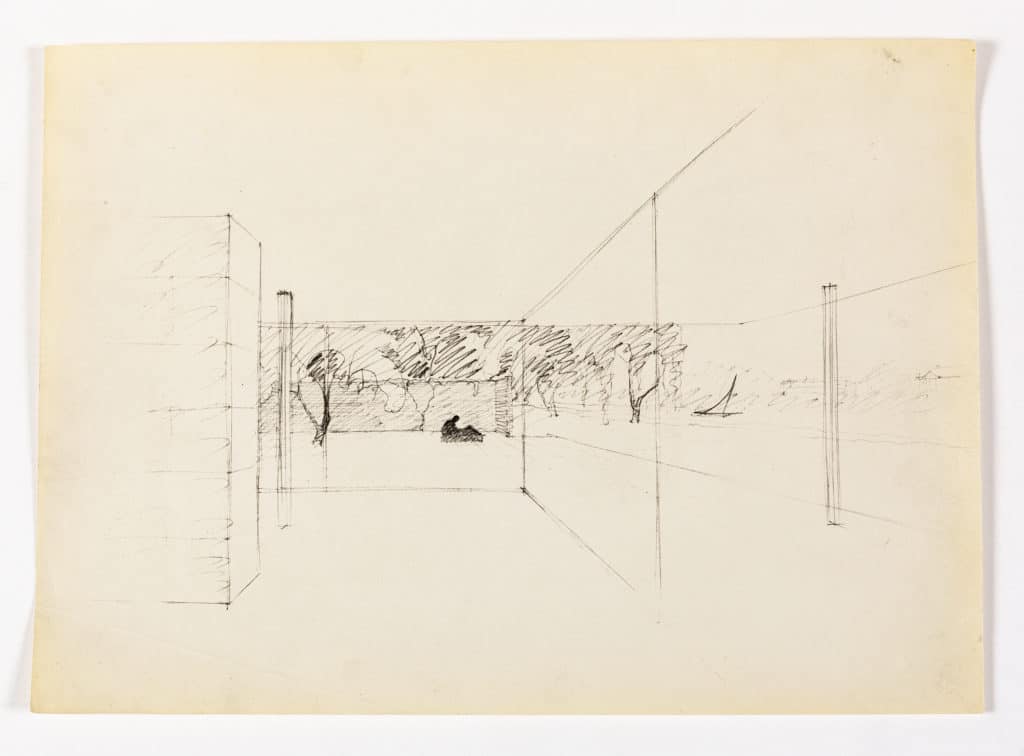

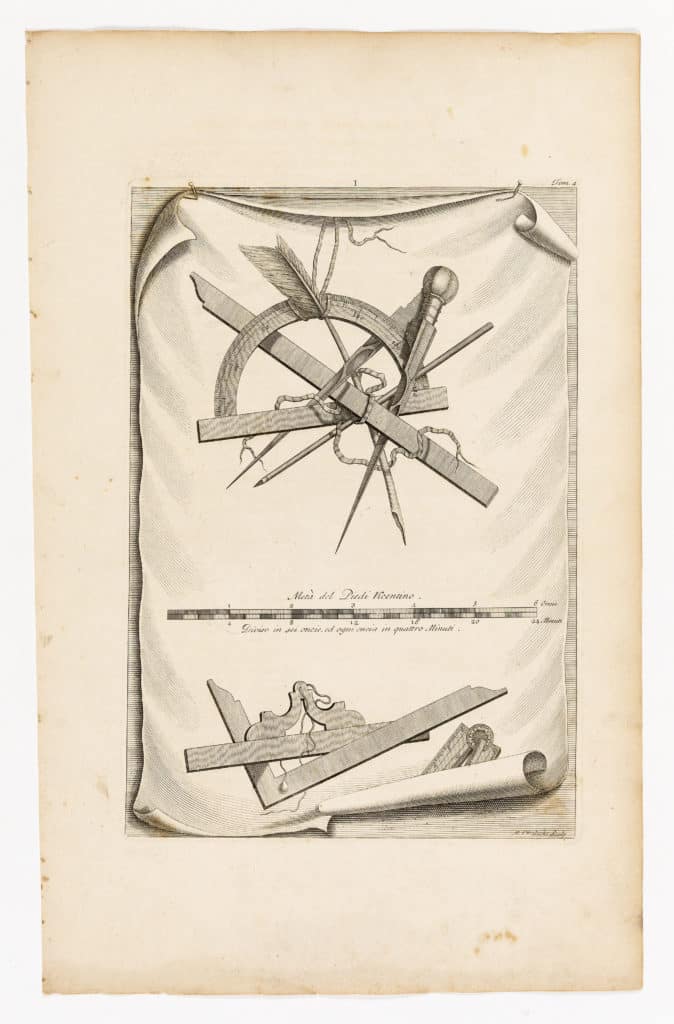

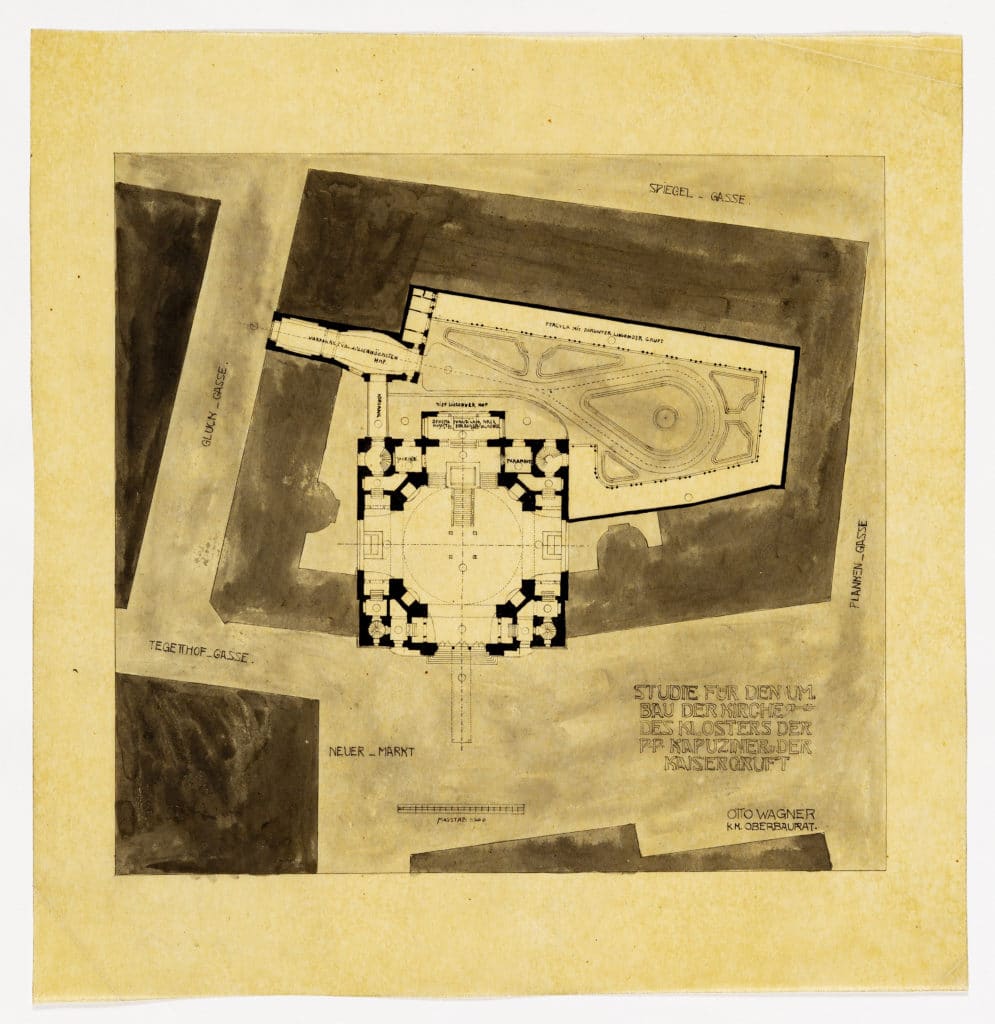

Inside a room formed from monolithic slabs of spruce were two large plan chests and an old exhibition table on a floor of cedar timber boards. At the far end of the room was a stove, which I didn’t use. The room was lit by three skylights and three lamps hung from the ceiling. One side was lined with cabinets and the other with upholstered boards. At various stages of my stay these upholstered boards displayed, starting from the far end of the room, portfolio drawings taken by Mies to an interview for a professorship; drawings for the façade of the Basilica of San Giovanni in Laterano by Luigi Vanvitelli; three sheets of model dwellings in Bruton with a particularly clear depiction of their sanitary provisions; a small and precise ground plan by Otto Wagner, on a square of paper, possibly for publication; a frontispiece from an early edition of the ‘quattro libri’, engraved by a Dutchman; a perspective of an unknown subject, by an unknown draftsman, for a project in Paris.

Nothing seems simpler than making a list to describe my experience, but in fact it’s much more complicated than it seems. Did I leave something out? Did I get the details correct? (Was the engraving made by a Dutchman?) Despite its incompleteness a list is necessary. It seems to me that its verticality, running counter to the horizontality of writing, offers a glimpse into my experience. By making a list of these drawings I am imposing a structure that attempts to replicate their display in the room. In reality I saw these drawings alongside, before, and after other drawings. A list can attempt to capture a moment – the drawings on the display boards – but it fails to describe my overall experience. A list fails because what I experienced was both successive and simultaneous. Language can represent the former but struggles to depict the latter.

Simultaneity is impossible in any other collection, where my journey works differently. Usually I know what drawing I’m looking for, possibly having already seen it reproduced in a publication or on the Internet. I search for a drawing on an online catalogue. Having made an appointment, I attend a location at a certain time. I can usually only ever see the drawings I’ve requested. (Despite this, I am overly nosey and always look at the material requested by other researchers). I tend to look at the drawings one at a time and my behaviour is quite stiff: I observe, measure, record. I’m not always sure that I enjoy looking at the drawings. I see it more as a form of examination. The enjoyment comes later when I study a photograph of the drawing alongside my notes, and then the exploration begins, away from the drawing itself.

Another list. These were the things I looked at on Tuesday 22nd August, mostly in the afternoon. Three of the five sheets of drawings sent by Schinkel for the Tilebein House; a ground plan by Aldo Rossi, collaged together; a church at the junction of two roads; in a Fed-Ex box, the sketchbooks of Peter Märkli from around the time he was working on La Congiunta, each book a different size depending on the gauge of his jacket pocket; William Wilkins’ survey drawing of the Holy Sepulchre in Cambridge; a drawing of a mask by Gio Ponti made first thing in the morning; a rendered elevation of Tyringham Hall, with the building in orthogonal projection and the landscape in perspective; Louis Kahn’s drawings for an office building in Kansas City; Anthony Salvin’s copy of one of Wilkins’ published survey drawings of the Holy Sepulchre; Peter Wilson’s studies for a public convenience, made with the combination of watercolour pencils drawn both precisely and rubbed over a uneven surface, possibly a textured paving slab; a model for a music room by Fontaine, at first flat and then assembled as it was discussed.

Order and hierarchy have always been an integral part of collections, perhaps even their purpose. In her book on miniatures and collecting, Susan Stewart discusses how collections replace history with classification, ‘thereby making temporality a spatial and material phenomenon, its existence dependent upon principles of organisation and categorisation’. [2] Viewed as a collection, Drawing Matter is different from this – its organisation is looser and allows itself to be adapted to the desires of visitors. And unlike many collections Drawing Matter does not attempt to construct a past from a set of presently existing pieces. Instead, the interest is in the drawings themselves as a key part of artistic and cultural practice: their materiality, peculiarity of conventions, and the residue of ideas that remain on their surface.

Notes

- Between the previous two sentences there was of course a host of interactions: welcomes, introductions, coffee, laughter and discussion. It was accompanied by at least one if not two dogs.

- S. Stewart, On Longing, Narratives of the Miniature, the Gigantic, the Souvenir, the Collection (Baltimore, 1984) p.153.

– Matthew Wells