Processing Process

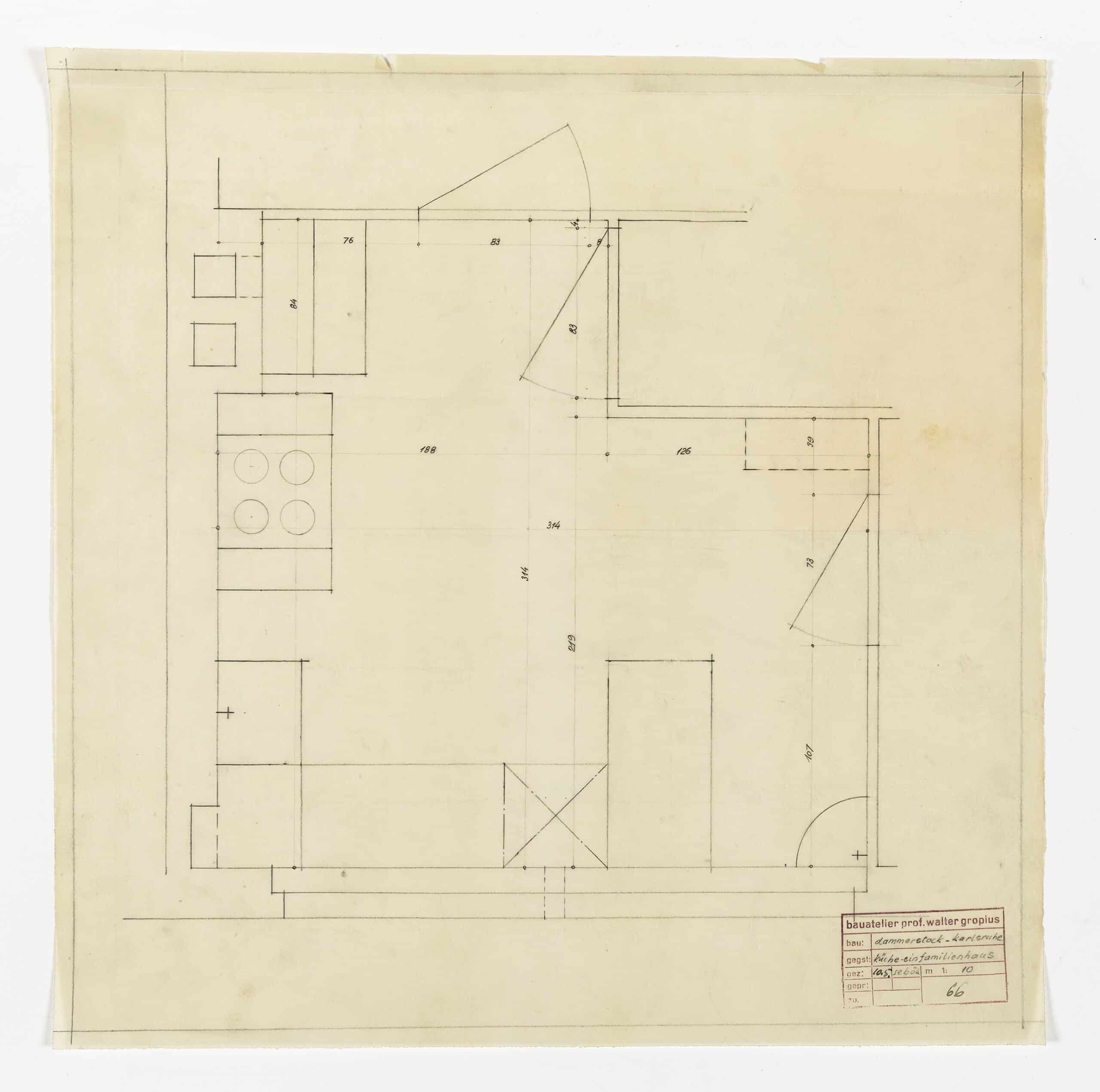

It is not Walter Gropius’ fault that his drawing for a single-family row house is strikingly dull. Even the towering figures of architecture, those revered creators of space and form, must, at times, strip their visions down to something much simpler. Clear, unadorned, almost utilitarian sketches become the necessary language through which design is conveyed. This 48 × 48cm sheet economically outlines a kitchen’s dimensions and schematic layout at a 1:10 scale. Nothing more.

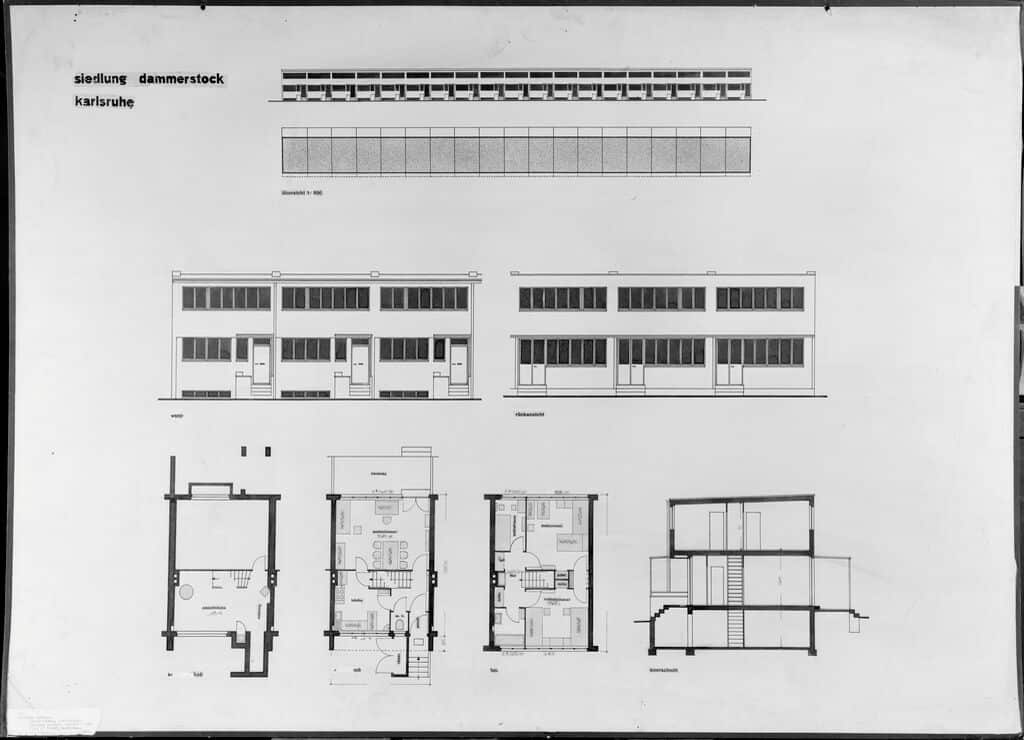

This pencil-on-trace paper sheet does not have the polish or aesthetic import of this ink-on-paper presentation drawing of the same project in the Harvard Art Museum collection. Most would see the Harvard drawing as ‘important’. It’s twice the size of the one on trace, inked with sharp clarity, and comprehensive in its scope: plan, section, elevations. It reads like a final statement. The 1929 Dammerstock-Karlsruhe housing project appears fully formed on paper. That clean correspondence between drawing and building, between idea and execution, is perhaps comforting. But this is a drawing that offers certainty, not inquiry. It stages architecture without revealing the work of making architecture.

By contrast, the small kitchen plan on trace is unassuming but honest. It was drawn to test proportions and layout, an exercise in design calibration. But more than a test, it is a moment of vision: a tool for seeing whether the organisation makes sense, what revisions might follow, and what remains unresolved. This drawing is not about display but discovery. It records the dialogue between eye, hand, and idea.

What makes architectural drawings compelling is not their polish but their capacity to think through space—to visualise ideas not yet formed, to see what a building might be. Process drawings are the spaces where architects learn to see, using pencil and paper to test an idea, confront it, and respond. Drawing externalises thought. You put something down to look at it, to see whether it holds. The page looks back and asks: what next? When I spent a week rifling through the drawers at Drawing Matter’s new Covent Garden home, I wasn’t looking for masterpieces. I was looking for the moment when a drawing becomes a way of seeing. That friction between thought and line, between what is imagined and what is seen, is where the work happens. Whether a starchitect or student, the impulse is the same: draw in order to see. These sheets are not evidence of conviction but of curiosity. They remind us that process drawings are not records of what one already knows—they are encounters with what one hopes to understand.

Asplund’s Window

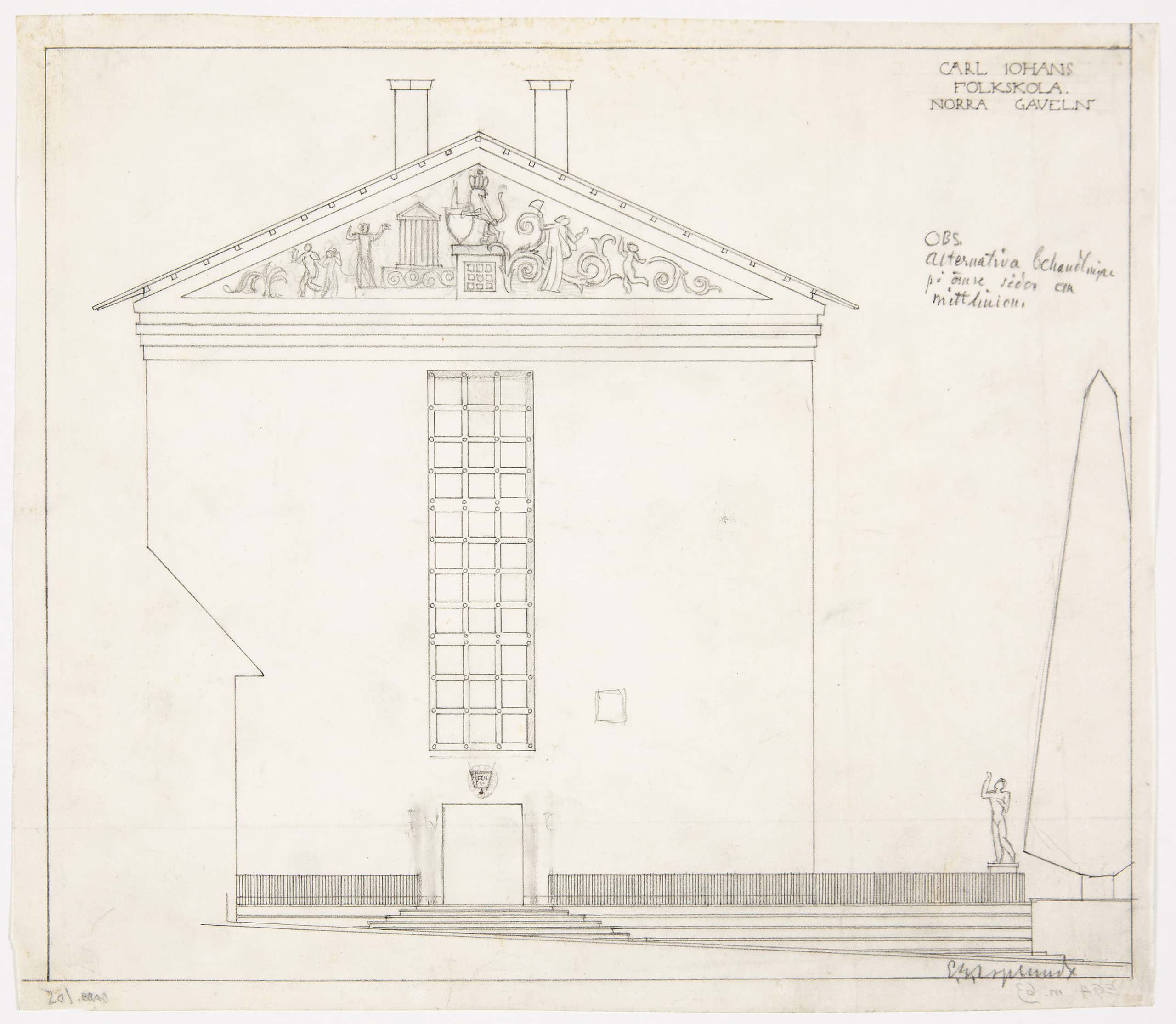

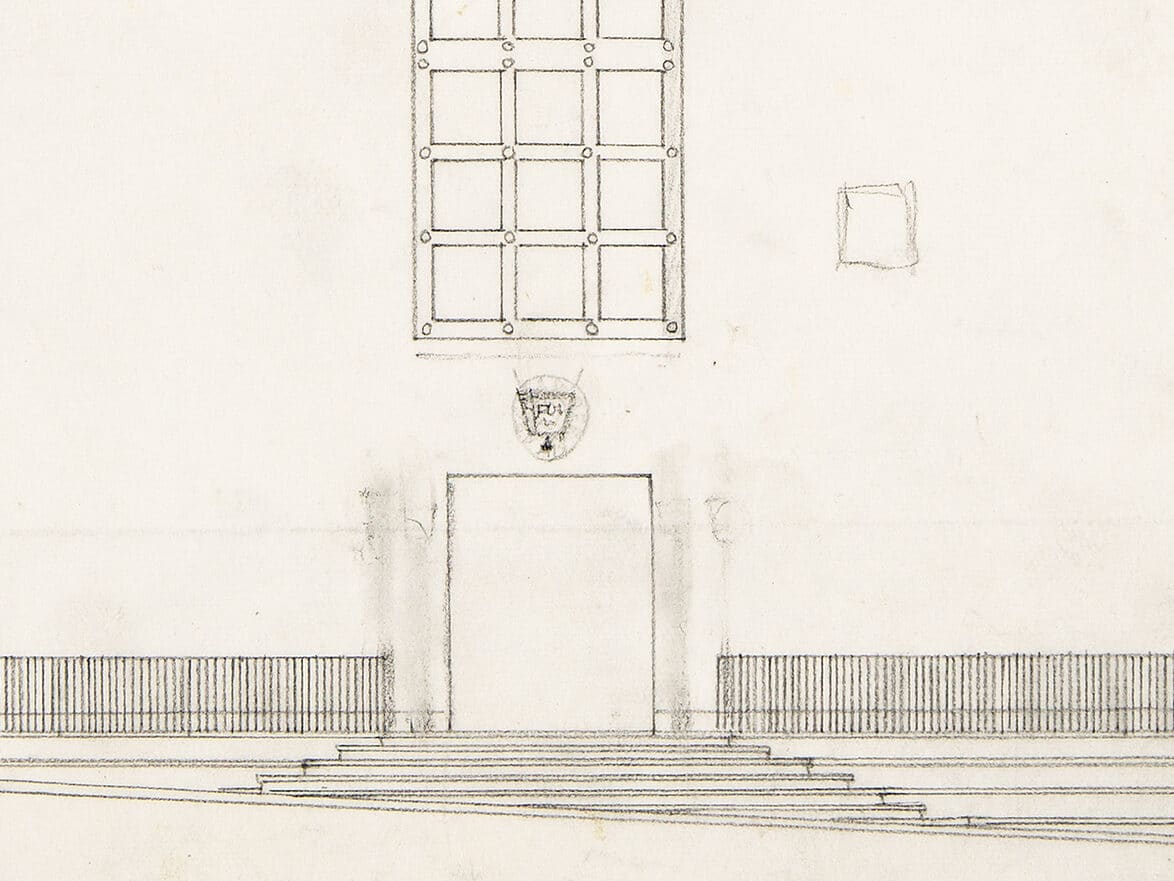

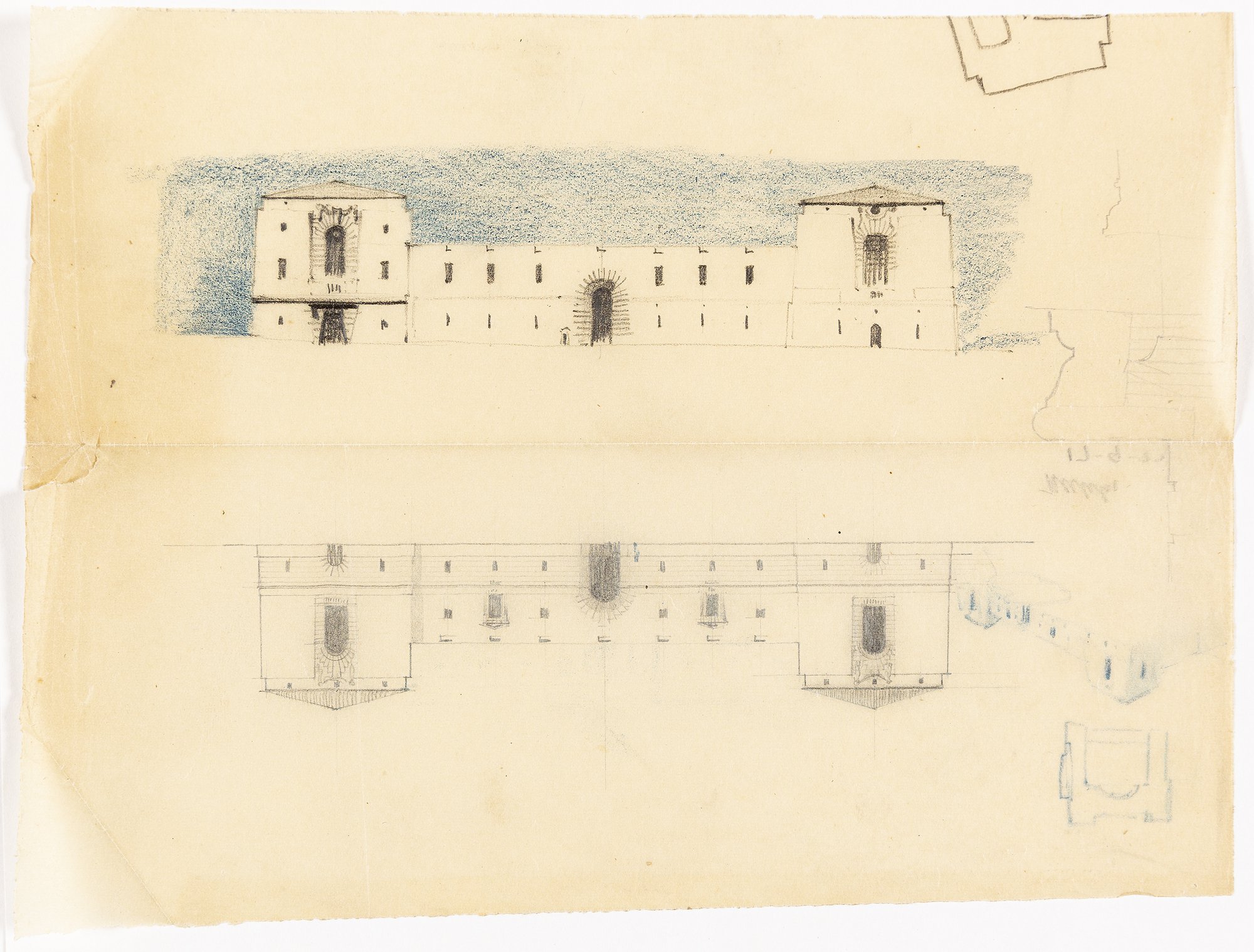

This 1921 elevation of the Karl Johan School in Gothenburg closely resembles the final building. At this stage in the design process, Erik Gunnar Asplund had likely arrived at a scheme that satisfied the programme and articulated a coherent architectural vision. The drawing is tidy, nearly resolved. But within this otherwise complete façade, two small moments interrupt the surface of confidence.

Low on the page, just to the right of the vertical window array at centre, Asplund has added a small freehand square. It is tentative; it doesn’t belong to the drawing’s ruled linework. The architect quizzed himself: ‘Is this composition too symmetrical? Should I add an offset window? Let me see…’ The addition is speculative, a moment of testing. Asplund drew it, and once again stepped back to look at it. He did not erase it, but it is not present in the final building.

There’s another change, more subtle but equally telling. The entry, as drawn, once had pilasters flanking the door. Their ghost remains in faint erasure marks. At some point after drawing them, Asplund decided they didn’t belong. The final building has a plain, unadorned entrance.

A quick sketch that leads nowhere. A deletion that holds. These two gestures—a scribbled square, a vanished pair of columns—are insubstantial edits in relation to the overall design. But they preserve a trace of the architect mid-thought. This is what process drawings offer: not only what the architect intended, but what they considered and abandoned. This is not a drawing to formally display an architectural idea, but a drawing that makes space for re-seeing it.

Lutyens’ Fold

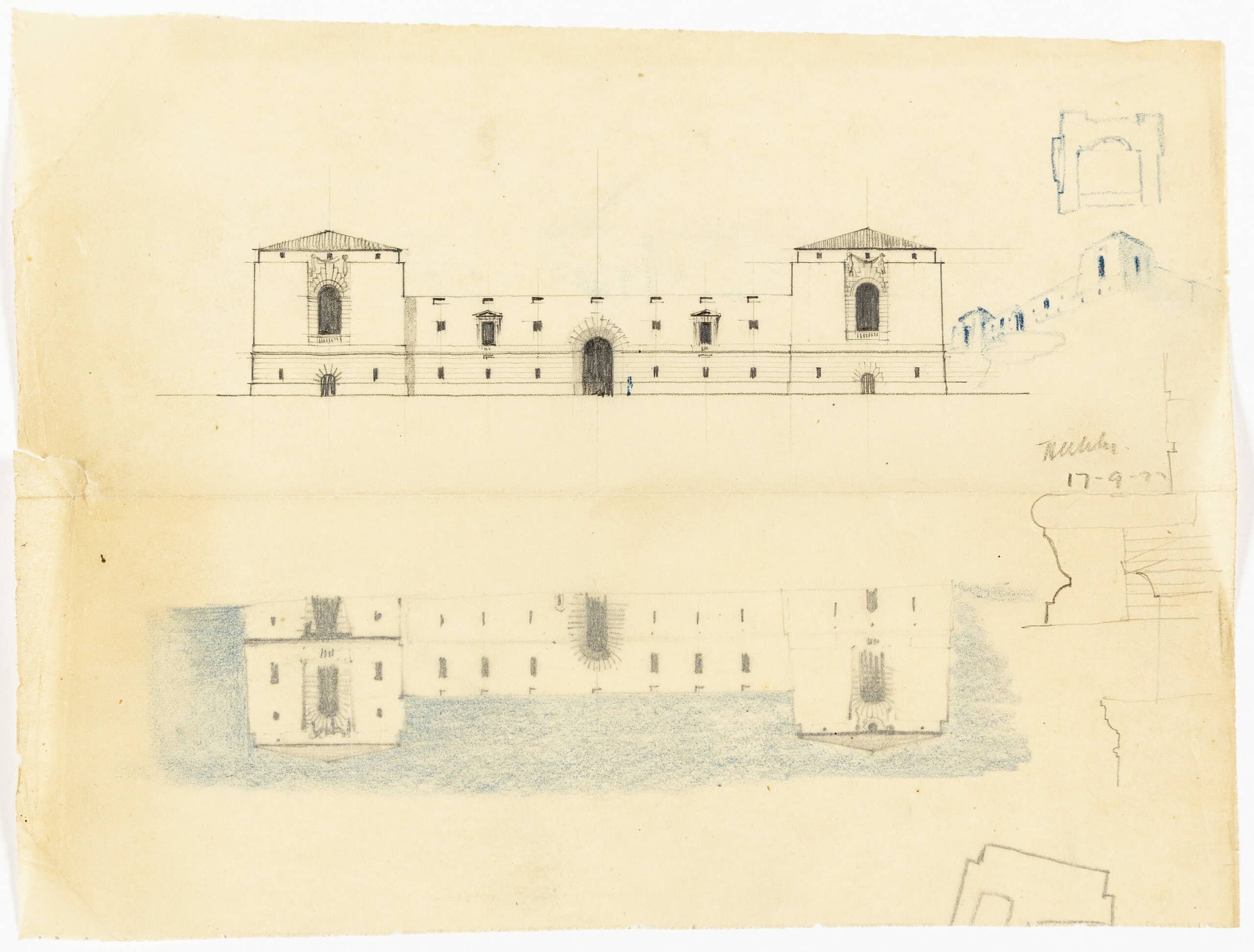

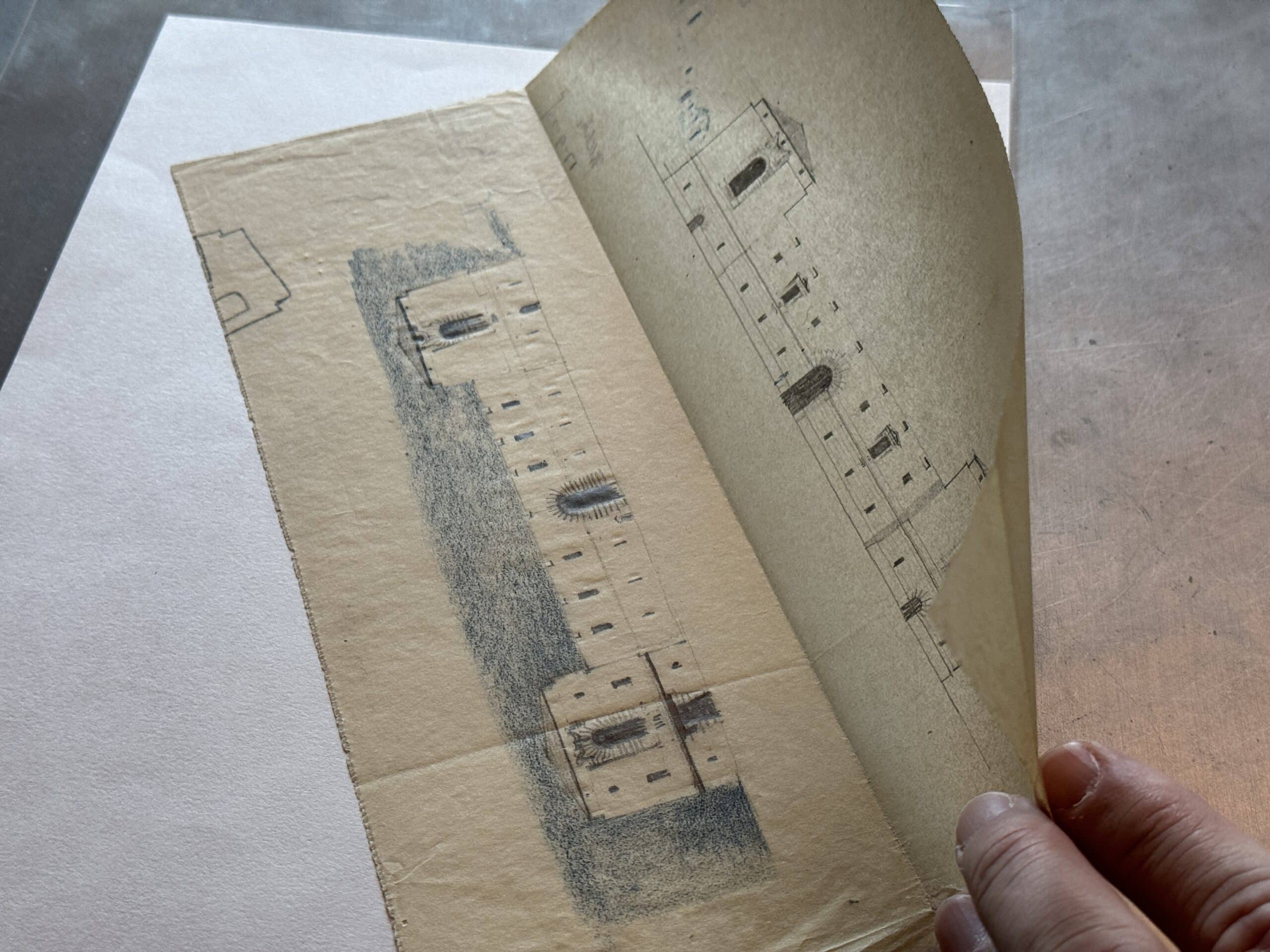

This may be the most elegant drawing I saw at Drawing Matter. Modest in size— smaller than 200 × 250mm—it is drawn on tracing paper, its recto and verso offering near-identical visions: a long building elevation mirrored below, like a reflection in water. Along the right margin, a constellation of marginalia: moulding profiles, an oblique upward view of the proposed façade, a swift study of a courtyard plan—each a fragment of thought caught in passing.

But the quiet hero of this drawing is the fold. A single horizontal crease divides the sheet, separating two versions of the same façade. When folded, one design ghosts over the other—a clean overlay, where one thought hovers above another. It’s not difficult to imagine the moment itself: Lutyens, standing over the completed elevation, formulates a new direction. He folds the paper upward and redraws. There’s no hesitation, no reaching for a new sheet—only the urgency of capturing the idea before it slips away.

The crease changes how we encounter the drawing itself. Most architectural sheets recede into image—the paper disappears into representation. But this one asserts its materiality. It is not only meant to be seen, but handled. The fold insists on the drawing as object, not merely illustration. The drawing becomes a tool for physical engagement, inviting interaction that makes examining it a temporal experience.

That temporality is what the drawing ultimately stages. Folded and unfolded, it becomes performative: a choreography of revision, a reenactment of a moment in design. Most drawings conceal their sequence; we rarely know which line came first or what change prompted the next. Similarly, layers of trace paper are rarely preserved in order—sketches scatter, get shuffled, or vanish entirely, leaving behind fragments with no clear beginning or end. But here, the steps are fixed: a drawing, a fold, a response —captured not in a loose stack but in a single object. And at Drawing Matter, you can perform it yourself: refold the sheet, trace the ghosted lines, inhabit the instant when one version gave way to another. We do not know which idea Lutyens kept, or whether he kept either. But we know which came first—and that continuity of thought, preserved in paper, is a rare thing.

As-Builts

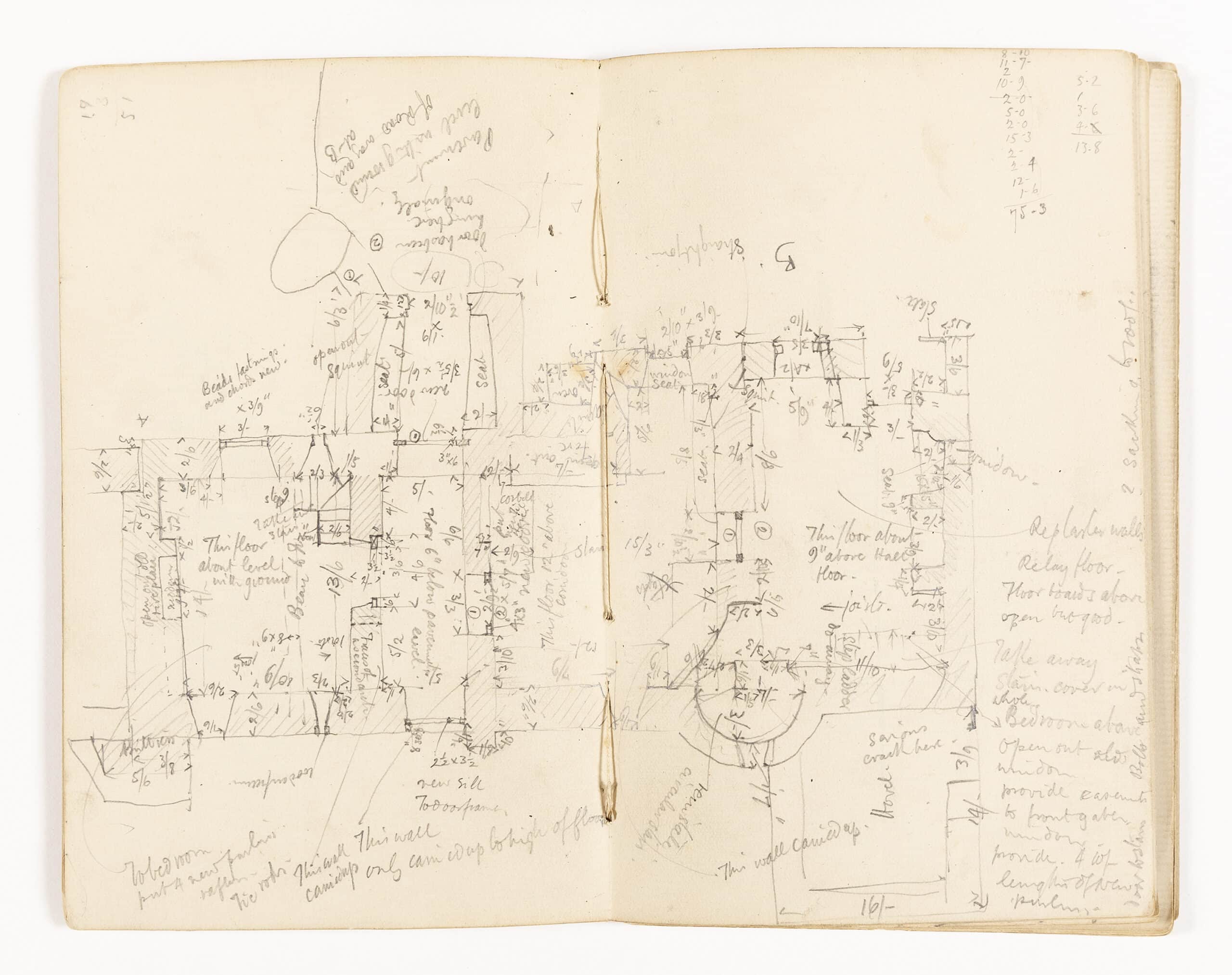

If, like me, you once served time as a young architecture intern sent to measure an existing building for as-built drawings, Detmar Blow’s sketchbook spread from 1896 might awaken a familiar unease. There is a particular tedium to this kind of work—crawling through dusty rooms, extending your tape measure from baseboard to crown moulding, slowly accumulating the raw data of architecture. It is a vital task, if unglamorous.

But it is also deeply intimate. Before the advent of laser rangefinders and 3D scanners, architects built their understanding of space by tracing it slowly, bodily. You walked the perimeter. You reached, stooped, craned. You pressed your palm to every surface, made a line, and recorded a number. Ceiling heights were noted. Electrical outlets marked. Material transitions logged with care. The building revealed itself not all at once but incrementally, through the steady accumulation of measurements.

I can see Blow walking around this house. As he turns a corner, so does his sketchbook. His measurements and annotations change orientation throughout the drawing. He rotates his sketchbook to keep the wall in front of him horizontal as he draws. Aside from sidebar notations, there is no clear definition of ‘up’ in this drawing. This drawing is a tactile reminder of the physical measuring process. The architect rotates around the building, hoping the lengths total a tidy circuit. The sketchbook apes the architect’s rotation in miniature, turning in his hand as he pivots around the space.

The drawings we’ve seen so far—by Gropius, Asplund, Lutyens—live in the generative space between concept and construction. But not all process drawings move in that direction. Some face the other way. Blow’s pages are as-built studies: records of a house that already exists. And yet, they are no less rooted in process. These lines are not made to finalise a design but to begin one. Before proposing a renovation, addition, or reimagining, the architect must first understand existing conditions. Blow’s drawing is an act of architectural seeing—of moving through space with the eyes and hands of someone preparing to intervene. He does not simply observe the house; he constructs it anew, line by line, through his body moving through space.

Pichler On the Go

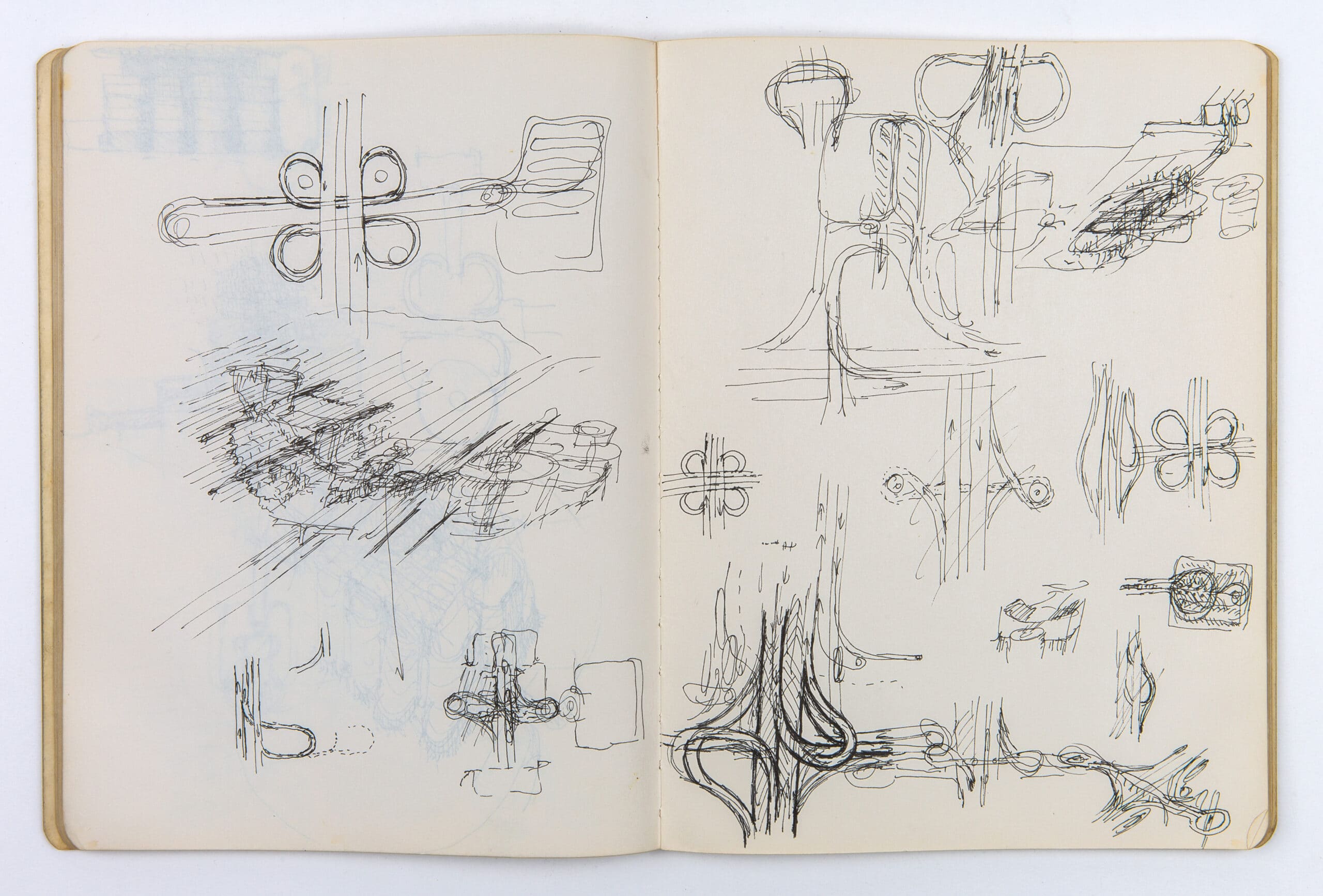

There’s something disarming about finding Walter Pichler’s work in a schoolchild’s notebook. The familiar black-and-white marbled cover—ubiquitous, utilitarian—feels worlds apart from the monumentality of his usual forms. This ‘Composition’ book was likely picked up during his 1963–64 travels in the United States. It wasn’t chosen for posterity; it was bought in haste, out of necessity.

Inside, the sketchbook is mostly what we expect from Pichler: a procession of internally driven forms—idealised and siteless designs as part of ongoing, personal architectural inquiry. But pages 47–48 break that rhythm. Here, we see something different: an architect looking outward. Drawings of what appear to be studies of the American highway system, with looping cloverleaves and soaring interchanges, suggest a moment of observation, of visual study. Yet even as he sketches what he sees, he begins to transform it. On the left, a terraced landscape with cylindrical forms suggests—perhaps—a Pichler-ised highway interchange, where looping ramp voids solidify into mass and level roadways become cascading architectural tiers.

What makes this page spread so compelling is its dual nature. It seems to oscillate between observation and invention. Pichler is looking and drawing—studying how these engineered systems work. But he is also wondering: what might they become? The drawing tests a visual logic: take the scale and infrastructural convention of the American highway and translate it into architectural form. Will it hold? Can it live outside the page? Or was it just a sketchbook fantasy, a capriccio never meant to go further?

Starting Out

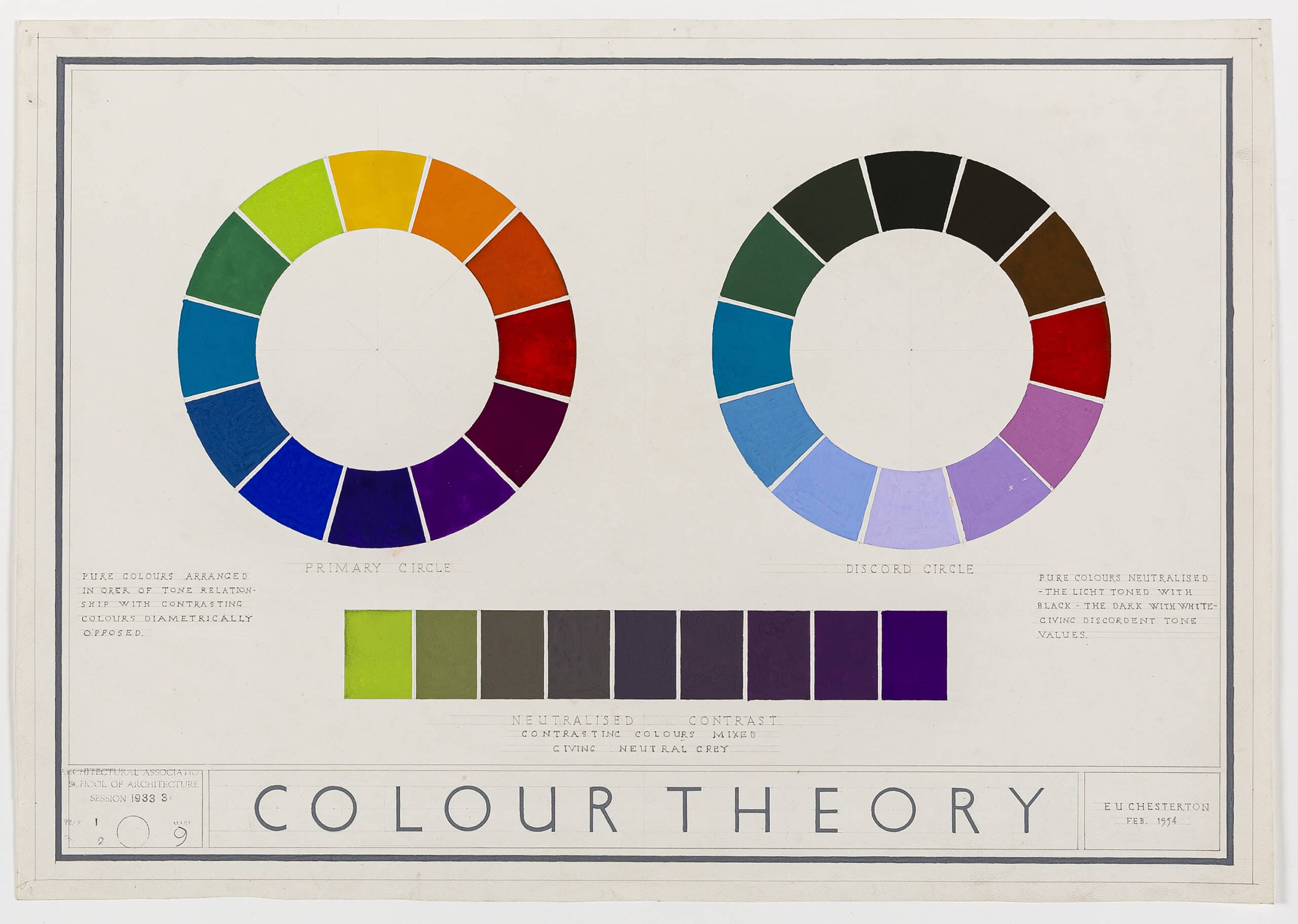

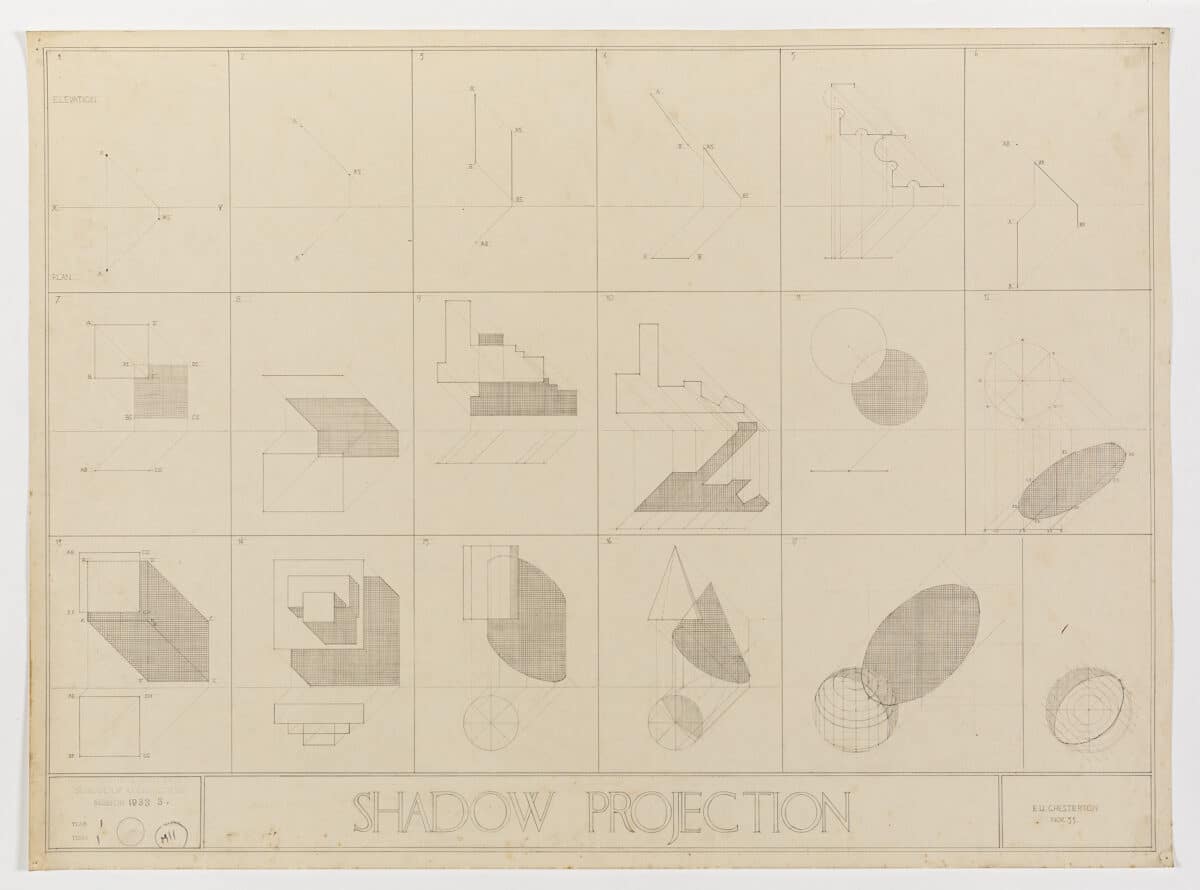

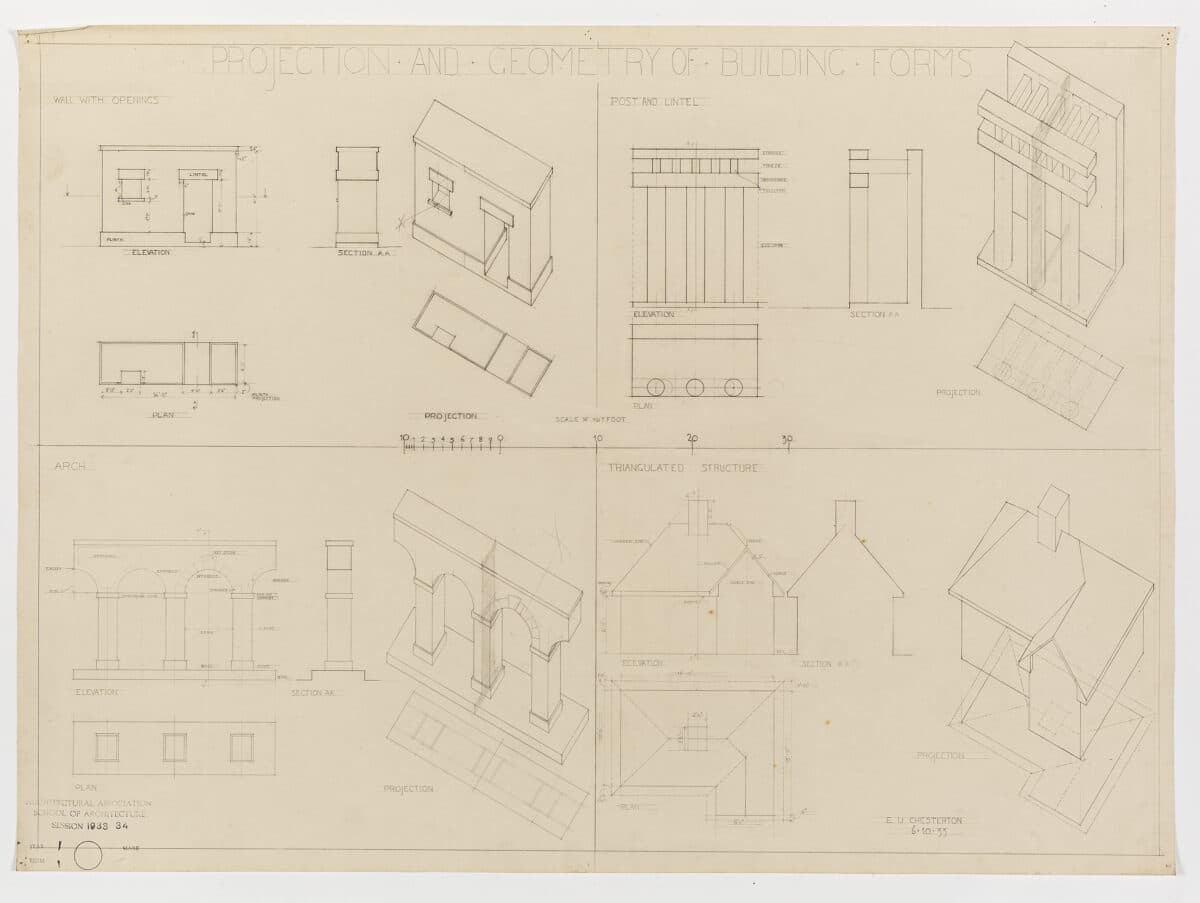

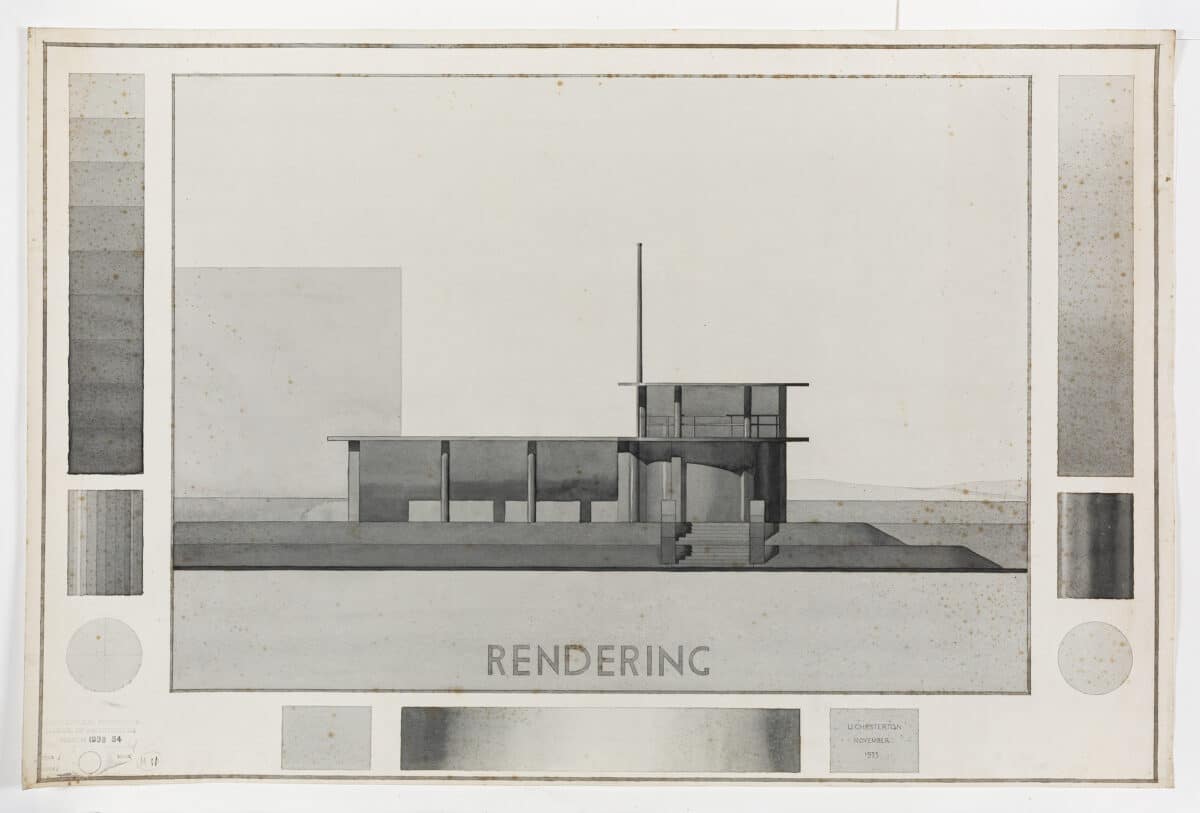

In 1934, Elizabeth Chesterton entered the Architectural Association in London. Drawing Matter holds a suite of her student work from that first year—a collection of measured, meticulous drawings that reflect the rote demands of architectural training more than any early expression of personal style. These are not the stirrings of a future master, but the careful products of a student learning to follow instructions, to meet expectations, to see what her instructors told her was worth seeing.

We can imagine them pinned up in rows beside dozens of others, each one answering the same tightly defined prompt. Their uniformity wasn’t accidental. It was instructional. At this stage, the student wasn’t yet the author of their own seeing. This wasn’t a space for personal vision, but an initiation into a visual discipline.

The drawings were not speculative design propositions—their purpose was fulfilled only when someone else, a tutor, responded. That response did more than assess. It modelled how to see. The tutor’s critique shaped perception: what to notice, what to ignore, what to revise. The student looked at the drawing, but didn’t yet know what to see. They borrowed the tutor’s eyes. In that surrogate seeing—through repetition, correction, calibration—a discipline begins to settle in. A visual literacy is formed that might, over time, deepen into an iterative practice: a feedback loop of drawing, seeing, and drawing again.

* * *

We call these drawings ‘process drawings,’ as if they were inert byproducts of design—passive markers on the way to a final form. But their significance lies not in what they precede, but in what they do. They are not merely part of the process; they are acts of processing. A better name might be ‘processing drawings’—drawings that do not simply document but actively engage, shaping understanding as they go. These marks on paper are the residue of seeing, thinking, and deciding—intertwined gestures that bring architecture into focus. We often treat ‘process’ as a noun, something complete and contained. But these drawings reveal process as a verb—an act unfolding in real time. They are evidence of the architect not merely designing, but working to understand the world through drawing: to see it more clearly by drawing it into being.

Pablo Garcia is an Associate Professor at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago. His creative and scholarly work explores the historical and speculative futures of art and technology relationships, focusing on drawing as both technical practice and conceptual inquiry. He is the creator of DrawingMachines.org, an online archive tracing five centuries of mechanical and optical drawing devices, and, since 2013, has produced the NeoLucida, a contemporary reimagining of the camera lucida, a 19th-century optical drawing aid. Garcia holds architecture degrees from Cornell University and Princeton University.