Richard J. Neutra: Visitor Center at Gettysburg National Park

In 1941, the US National Park Service acquired one of numerous versions of a 360-degree cyclorama, an in-the-round painting of the turning point in the great rebellion against the American union at Gettysburg in July 1863. First painted 20 years after the battle, the panels filled a drum 80 feet in diameter. In 1957, as part of ‘Mission 66’, which sought to vastly enhance and expand visitor and interpretive centres in the national parks by engaging distinguished modern architects to design them, Richard Neutra, then in partnership with Robert Alexander, was invited to develop a proposal for the Gettysburg site that would find a more dignified observatory for the surviving cyclorama, provide an overview of the battlefield itself, and expand services to the increased number of visitors anticipated during the centennial of the Civil War.

Neutra’s conception of the programme far transcended this brief. Believing that ‘the sad memory of a still painful rift could by the erection of a monumental building… commemorate what mankind must preserve as a common aim of harmony’, his designs called for a site of international and human reconciliation served by a 300-foot-long exhibition pavilion; an auditorium; a rotunda to encase the cyclorama rising 60 feet from the ground; a plaza extending into the landscape overlooking the field of conflict from the point of view of the painted panels; and – two features lost in the eventual development – an observation tower and a reflecting pool designed to mirror that ‘everlasting sky that covers all of us’.

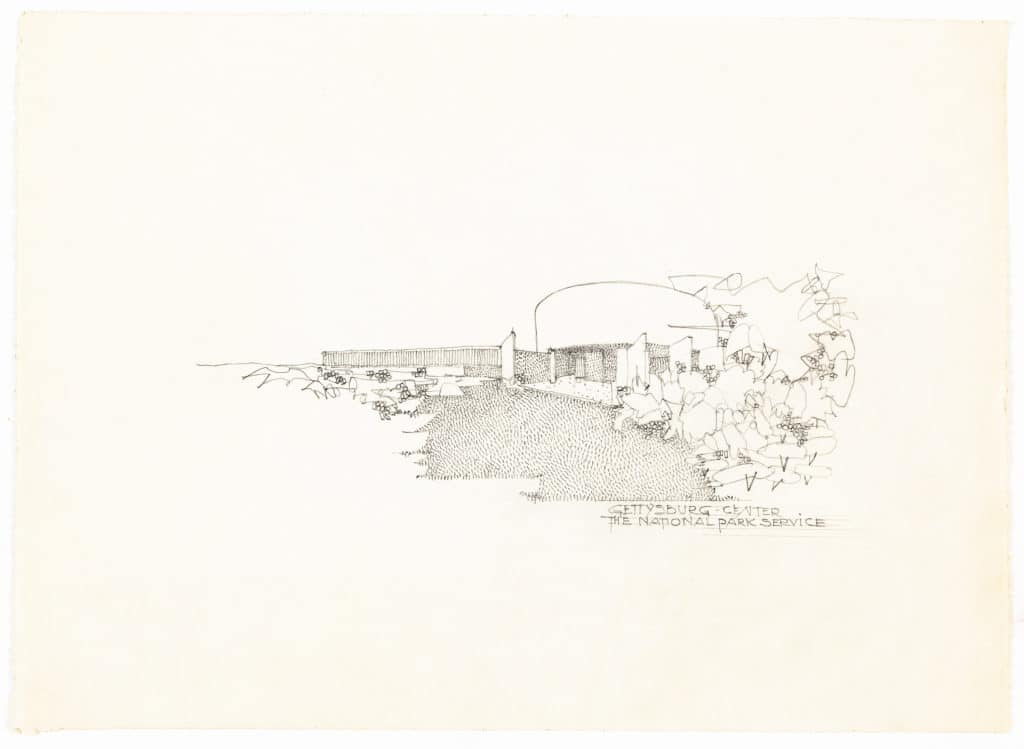

This tiny suggestive drawing of a vast project is an oblique view of the east elevation, shown close to the form in which it appeared late in 1958 as a final design known as ‘Scheme P’. Probably conceived for publication and exhibition while the project was still in construction, it distils to something like an abstraction what Neutra called the ‘climax’ of a visitor’s journey, when the great retractable doors to the rotunda ahead and the auditorium to the left open across a speaker’s platform to ‘a tremendous, gently rising outer gathering ground’ – a point of symbolic re-unification within the landscape, shaded by the fateful grove of trees at which the Rebel troops were halted, a swath beneath ‘the everlasting sky over all of us’. That platform Neutra envisaged as a ‘rostrum of the prophetic voice’, where world figures would find words equal in their power to what he called the ‘grand, short, wistful and prophetic’ address with which Lincoln had first memorialised the site.

Neutra’s mastery of framing and the pencil point emphasise the universality and neutrality he was striving to achieve when he proposed that the monument ‘should play itself into the background’ and ‘not shout out any novelty or datedness’. Alternating hard and soft leads, the drawing fills less than a third of the sheet, and the architecture less than a third of the pictured landscape. Perspective is realised with tiny gestures, like the added weight of the pencil on the top of the piers, or the added density of pencil points to suggest shadow under the overhang. Contrasts between the hard geometry of walls and the fluent shapes of vegetation are rendered by varying the length of line: short sharp strokes to silhouette the building and long sinuous strokes to shape the outline of the trees, where the pencil scarcely leaves the page – a technique that requires a scrupulously poised hand to avoid smudging. And everything, including the use of a single improbable tree-limb to point us to it, converts the blankest and least animated element in the composition – that great 35 foot high floating drum – into its primary and only volumetric subject, casually resolving with utter finesse the draftsman’s conundrum of how to show a cylinder in outline.

Federal administrators themselves recognised the monument as the culmination of Neutra’s career and boldly honoured his extraordinary ambition in its execution. It was recently, despite a massive outcry, demolished.

– Nicholas Olsberg