River Arno

In Florence, the flooding of the River Arno on November 4, 1966 was of a magnitude not seen in almost 500 years of history. The city, built on this alluvial plain, was flooded and the river overflowed its banks, filling areas as far away as the Piazza del Duomo with muddy water.

The waters began to rise that morning and in less than 24 hours they had returned to their usual course, although almost as high as the Ponte Vecchio and with a strong current. It was a brief event, but intense enough to displace many Florentines, kill around 100 people, and leave a trail of destruction of a movable heritage of more than a million documents, mainly from libraries and archives, including books, immense manuscripts, paintings, and sculptures. That same year, Superstudio, an architectural studio made up of students from the University of Florence, began its activity.

Saving the city of Florence at this time was less about protecting its built heritage than rescuing these documents from the mud. The international attention that was given to this event quickly brought together a veritable army of young volunteers to save several kilometres of shelves affected by the torrent. The angeli delo fango (mud angels) arrived by their own means, from various countries, and offered to do all kinds of jobs, more or less qualified.

One of the effects of this ‘stirring of the waters’ was that, faced with the real threat of their imminent destruction, it gave a breath of life to these inanimate objects that would otherwise have remained in archives or out of sight and reach of the public: scaffolding was erected to study church murals up close, books were taken off the shelves, and transported in human chains across the city to safe places and, feeding the idealistic colour of this army, there is the report of Botticelli’s Magdalene painting having travelled, in broad daylight, in the back seat of a red Volkswagen Beetle convertible, from the Baptistery to Palazzo Davanzati: ‘a proto-Woodstock of high visual culture.’[1] Taken out of their context, removed from pedestals, assembled in unusual places, and in the middle of muddy rubble, the effort to alleviate this local event that had become a global tragedy had the momentary effect of giving new meaning to those inanimate, intangible objects, many of them inaccessible, bringing them closer to this group of art lovers, for whom Florence was the soul of Western civilisation. In those first days after the unexpected flood, the sense of emergency did not lend itself to wasting time in evaluating how to organise the teams or which methods were best for preserving the precious objects. Without always knowing for sure whether they were doing the right thing, book covers were removed, the mud from the pages was washed off with clean water, and the leaves were laid out to dry in unlikely places, sheltered under the gallery in Uffizi Square or on clotheslines in the boiler room of the train station. The work was done in a festive atmosphere, far from being a mechanical process:

‘You could hear music from someone’s transistor radio—it was the Beach Boys, usually—and the angels needed music, just as they needed to stop and smoke a cigarette, not just to relax but to keep warm, heating themselves from inside out. It was always cold and always damp where they worked, and often where they ate and slept. There was, of course, a surfeit of Chianti dispensed from immense demijohns just as there was limitless talk and laughter. People fell in love: with art; with one another; with themselves, because how often did you get to be a hero, much less an angel?’[2]

Among the thousand or so young volunteers who gathered here, there was a significant percentage of people with specific qualifications useful for the task of rescuing books and artistic objects. As well as students, there were artists, art historians, and restorers of ancient works. International campaigns such as the film ‘Per Firenze’, made it possible to raise money and bring together the greatest specialists and the latest techniques for treating works at risk.[3] The process of reorganisation and preservation became successively more systematised as it became clear that the response to the emergency would be followed by decades of great patience and economic cost. Cleaning and drying paper documents was just one of the concerns to be taken into account. Many of the books, due to the nature of their materials, would not even be suitable for this process because they would dissolve in the water. With the lack of fuel and the cold snap that followed in the first few months, the paper would soon be affected by mould and other contaminants. The speed of degradation and mould growth was difficult for rescue operations to keep up with.

Painting posed another kind of challenge. Cimabue’s Crocifisso, a painting on wood from the 13th century, had been destroyed to such an extent that only a third of its surface remained in usable condition. This was not the first time it had been restored. In this, as in many other cases, the question at the time was whether it would be more correct to restore it to the condition it was in immediately before the flood or, given such a level of damage, to bring it closer to the original condition it would have been in when it left the artist’s studio. The known techniques were not capable of solving a problem of this scale. Over the following decades, Florence thus became a field for experimenting and reinventing restoration practices and techniques. For paper documents, one of the techniques that already existed at the time was to preserve them by freeze-drying. This process, which is more common in the food industry, involves freezing very quickly in order to avoid the formation of ice crystals which, just like in food, damage the structure of the material’s fibres. The material is then dried in a vacuum chamber by passing the water contained in the solid state into a gaseous state.

‘The study cites two methods in current use for drying water-damaged archival and library materials: vacuum freeze-drying by sublimation and vacuum-drying by evaporation. The emphasis is on freeze-drying. Here, the wet materials must first be frozen. This produces a condition of total stabilisation which, in turn, provides an unlimited span of time to think, plan, and decide what course of action to take.’ [4]

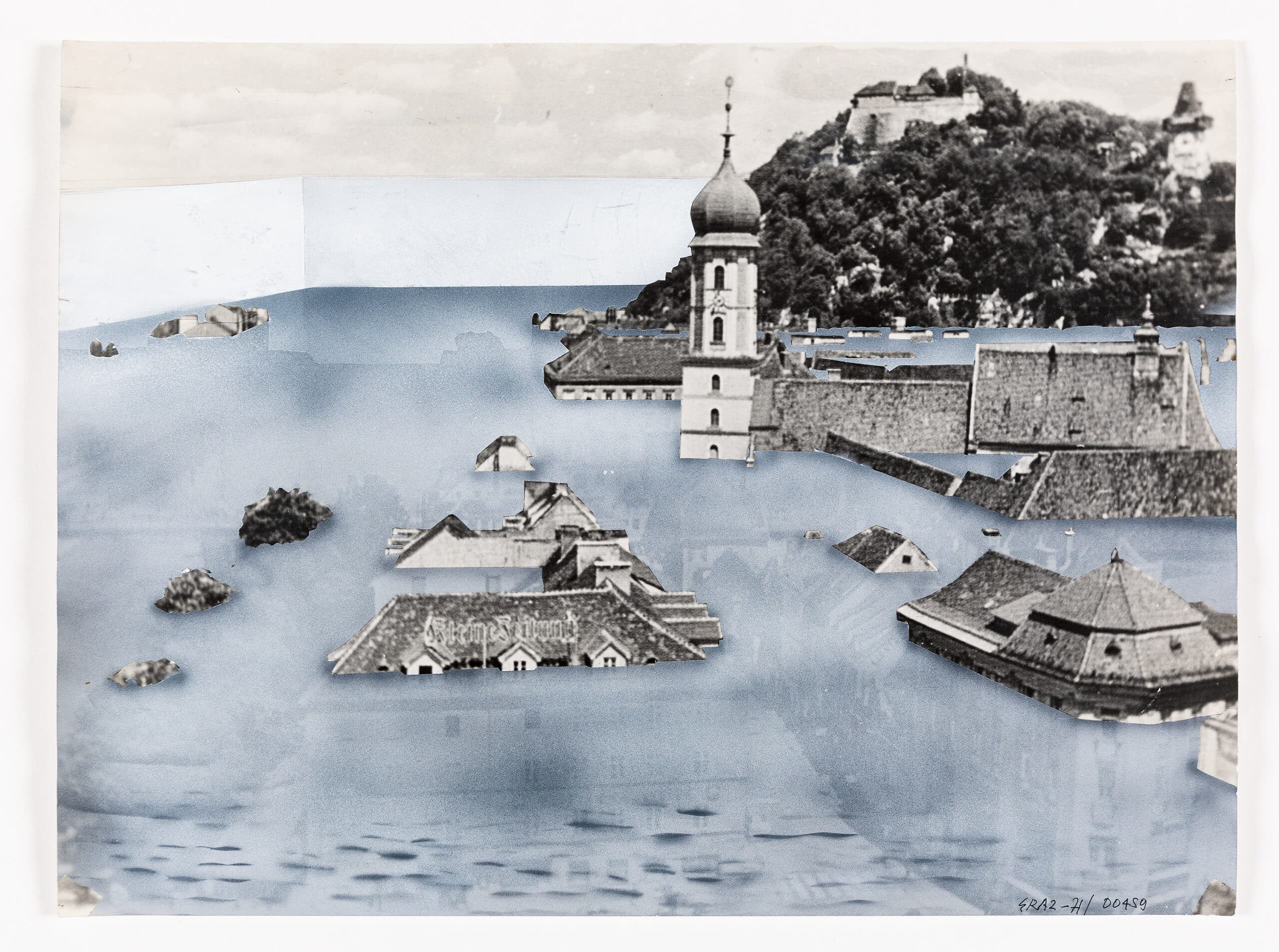

There is no reference to the use of freeze-drying specifically in Florence, but the description of the process, especially the possibility of gaining unlimited time to think, resonates with the provocative proposal that Superstudio would present for the Neue Gallery in the Austrian city of Graz in 1971. The intervention would involve flooding its centre, and freezing it in the same way with dry ice (Un Cubo d’aqua per Graz).[5] What was, like most of his proposals, ‘paper architecture’ (as it was more an illustration of an argument than a project to be built) would have the effect of leaving the city suspended, unchanged, for an indeterminate period of time, which would simultaneously be a way of preventing it from changing.

It was on paper, in fact, that the main arguments for intervention and safeguarding heritage were made. Italia Nostra, an organisation founded in 1955, before the Arno floods, has the mission of protecting and promoting historical, artistic, and environmental heritage, contributing to the construction of a certain idea of national identity. Its campaigns with public opinion, which are still active today, are recurrent, warning UNESCO; for example, of the threat of cruise ships over Venice or opposing the departure of Italian works from the territory (even temporarily), but also the return of foreign works to their countries of origin.

Superstudio, with their realistic photomontages, realised that mastery of the visual language, of the colour print magazines of the time (which they cut out to make the new images), was fundamental to establishing a dialogue, broadening the debate to the public. If the idea of national identity is a construction, so is the distinction of what is considered heritage and, going through various eras, which is the most significant and the most appropriate way to deal with it. The discussion around the reconstruction of Florence’s historic centre had already been going on for more than two decades, since the withdrawal of German troops in August 1944. The post-war destruction, particularly the dynamited bridges over the Arno, would revive a kitsch restoration tradition in the eyes of this new generation, ‘[…] a pastiche of Rationalist reinforced concrete structure and imitation of the Tuscan style […]’, not unlike the neo-renaissance interventions that had already taken place at the end of the 19th century.[6]

In the 1960s, both the rehabilitation of the historic centre and its expansion were contested as they were unable to cope with the increase in population and where the university student population was also doubling. The architecture students, in particular, demanded a voice in the renewal of the city and the education system itself. It was not the 1966 flood alone that inspired Superstudio’s initial theoretical formulations. The Superarchitettura exhibition, the founding moment that brought this studio together with their fellow countrymen Archizoom in Pistoia, had already been in preparation months before. However, the episode may have helped fuel this critical attitude towards history and its custodians.

In Salvataggio di centri storici italiani (Italia vostra) from 1972 (the year after the project for Graz), [7] the studio proposed saving Florence by flooding it, as a way of getting involved in the discussion about how to think about heritage. [8] In his photomontage, the city appears as a large surface of water, from which the iconic Duomo and Giotto’s bell tower erupt, around which sailing boats sail:

‘[…] if you really want to restore the situation, why just restore to the 19th century? Why not restore the renaissance situation? If you do that, why not the medieval situation? In fact, why don’t you go back to the Roman situation? And if you go back that far, why don’t you go back to the Pleistocene situation? In the Pleistocene situation Florence was a lake! And we figured out what the level of the lake was. We said ‘it’s really easy, we can do it. We have to dam the Arno River in a certain place. Leonardo did a study that showed it could be done.’ So we would dam the Arno River, and Florence would be a submerged city, which would be perfect for tourism. They could see the city by submarine instead of by bus!’[9]

With this provocation, they evoke both the traumatic episode of 1966 (which is still nearby) and the fact that, demonstrably, this place was a lake millions of years before. With this direct affront to Italia Nostra, they declare that the understanding of cities and their heritage was not necessarily shared by this generation, and certainly not by that group of architects. This attitude is only apparently iconoclastic because it only happens on paper. It was a way of questioning the very foundations of architectural practice, as a discipline that transforms (and predates) the territory. At a formative moment for their future practice, it is significant that they claimed to question the ground itself, either by replacing it with an abstract and continuous grid, or by flooding it. Also in this project, the construction of a cubic cage to maintain Milan’s characteristic smog, the landfill of Rome, or the drainage of Venice’s canals were mentioned as strategies for recovering city centres.[10]

For Florence, as for other Italian cities, where the weight of history and its heritage (in addition to the effects of the post-war crisis) seemed to limit the aspirations of these young architects, the aforementioned iconoclastic provocations appear evoking extreme natural phenomena: a deluge, a permanent fog, an eruption, or an extreme drought, transferring the responsibility for the destructive act to a divine entity or nature.

As early as 1975, the echoes of these proposals found a parallel in Mário Ramos and Fernando Barroso’s vision for Avenida dos Aliados in Porto. In Insurrectionary Organisation of Space, it was also the ground that was covered in sand, covering the space designated by power as a space of representation. The then architecture students, like the Florentino studio, expressed their desire to erase all the imposed, predetermined forms that conditioned their conduct, in favour of the search for true individual freedom: of thought, spontaneity, and creativity, ‘to question everything, if necessary, starting from nothing.’[11] The desert, as a symbol of the absence of references, with the instability and formal variation typical of sand dunes, eloquently illustrated this aspiration.

Despite this proximity in positioning, these Portuguese never crossed paths with Superstudio.[12] This common spirit of contestation and defiance of any kind of power can certainly be attributed to the air of time. Insurrectionary Organisation of Space was a clear reference to Fernando Távora’s book, which would give its name to one of the curricular units that is still taught today in the first year of the architecture course at the University of Porto (General Theory of the Organisation of Space), just as ‘Italia Vostra’ challenged the totalising vision of Italia Nostra.

Another similarity can be found in the tension caused between what was established as built heritage (or a monument) and an invention of nature: the creation of a dystopian scenario where, by design, the symbols of power are called into question, often in a state of ruin. The themes of ecology, the threat of planetary destruction, and the interest in ancestral knowledge are recurrent in these authors, who at the time were seen as alternative discourses to those established by power. In 1976 Ramos and Barroso envisioned the revitalisation of the São Vítor neighbourhood with the pedestrianisation of public space, with vegetable gardens and geodesic domes[13]; in 1978 Natalini and Frassinelli presented the survey of the tools and artefacts of Zeno, a Tuscan peasant, to the Architecture Biennale, giving visibility to ancestral wisdom, alternative ways of life and self-sufficiency.[14]

In all these proposals, care is also taken with the drawing, understood in a broad sense. Collage was a resource used by both of them, based on photographs and images cut from magazines, always with a sense of verisimilitude in the proportion of the elements and the technique of perspective:

‘It is probably unnecessary to know the rules of descriptive geometry by heart (I really don’t know them too well either), because today the help Adobe offers is substantial; however, the difficulties of inserting a building or an object into an environment give completely different results depending on how well the principles of perspective geometry are understood.’[15]

Barroso and Ramos also communicated their projects using conventional architectural representation tools: plans, sections, elevations, axonometries, as well as collages and elements from comics and photo novels.[16] In Insurrectionary Organisation of Space, there is a strict correspondence between the plan and the elevations of Avenida dos Aliados, which gives it, as in the other proposals, an ironic sense. The drawings, despite being thought of as a visual expression of a political and poetic claim, could actually be used to realise it. However, there would be no ambition or interest in seeing them built. Gian Piero Frassinelli, a founding member of Superstudio, would years later recognise the similarity between his Continuous Monument and the project The Line, a monolithic linear city, between two mirrored walls 500m high and 170km long, whose construction in Saudi Arabia was then about to begin[17]:

‘Seeing the dystopias of your own imagination being created is not the best thing you could wish for.’[18]

As this text was being discussed with the Drawing Matter editorial team, the collage ‘Florence as a Field of Maize’ emerged, establishing new resonances with the sand dunes, with their characteristic vegetation, proposed for Praça dos Aliados in the city of Porto: ‘The Monument had done its job around the world, and the city has been superannuated- it returns to find its hometown transformed into a “campo di mais”’.

Notes

- Robert Clark, Dark Water, Flood and Redemption in the City of Masterpieces (New York: Doubleday, 2008).

- John Imam, ‘Architects Dreaming of a Future With No Buildings’, New York Times, 16 February 2021, https://www.nytimes.com/2021/02/12/arts/design/superstudio-civa.html [accessed 12 April 2024].

- Per Firenze is the original title, translated into English as Florence: Days of Destruction. It’s a documentary produced by RAI and directed by Franco Zeffirelli in 1966, the month after the flood. It was narrated by actor Richard Burton, with English and Italian versions. This campaign was responsible for raising around 20 million dollars for the city’s restoration efforts.

- Peter Lang, Suicidal Desires, in Peter Lang and William Menking, Superstudio, Life Without Objects (Milan: Skira, 2003); in James McCleary, Vacuum Freeze-Drying, a Method Used to Salvage Water-Damaged Archival and Library Materials: A RAMP Study with Guidelines (Paris: UNESCO, 1987).

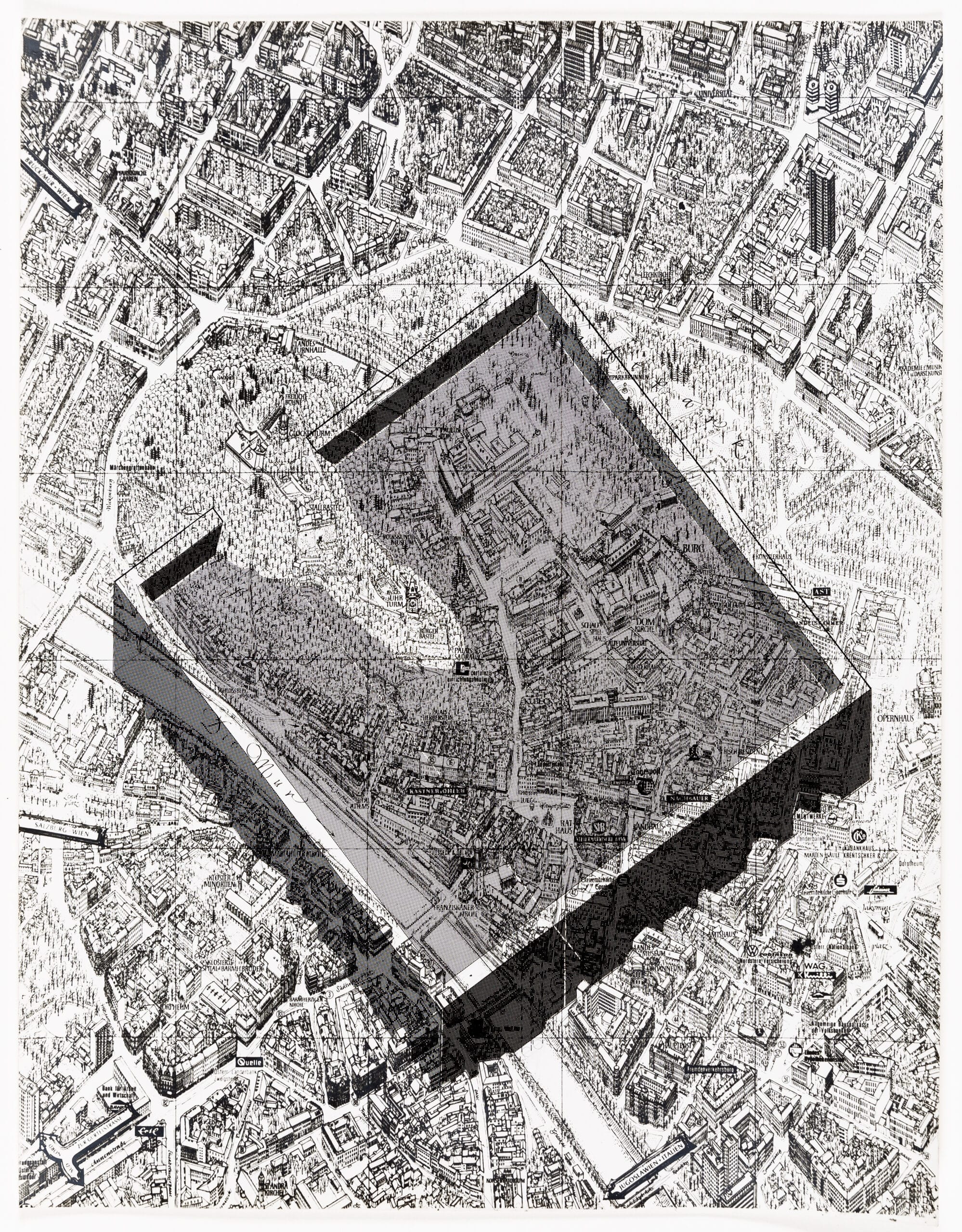

- The ‘Graz’ project (Superstudio, 1971) is deposited in the Drawing Matter Collection (2156.9). In this collection of drawings, photomontages, and postcards, in addition to the proposal for the Austrian city, there is a set of diptychs with postcards pasted side by side on cardboard of the cities of Graz and Florence with the title GRAZFIRENZECONTINUA inscribed in pencil. Also, in the Drawing Matter Collection, there is the map ‘Firenze, 1971’ (2074) where, on a military map of the city of Florence, a square is drawn to adapt Graz’s solution to the historic centre of the Italian city.

- Peter Lang, Suicidal Desires, in Peter Lang and William Menking, Superstudio, Life Without Objects (Milan: Skira, 2003); in James McCleary, Vacuum Freeze-Drying, a Method Used to Salvage Water-Damaged Archival and Library Materials: A RAMP Study with Guidelines (Paris: UNESCO, 1987).

- This project was published in IN magazine in May/June 1972.

- Laurence Allais, Designs of Destruction, The Making of Monuments in the Twentieth Century (Chicago and London: The University of Chicago Press, 2018).

- Gian Piero Frassinelli and Antonio Natalini, Superstudio: La Moglie di Lot e la Coscienza di Zeno (Venice: La Biennale di Venezia, 1978).

- The drawing boards for the Milan (AM 2000-2-139) and Rome (AM 2000-2-132) projects are composed of a photomontage and a sheet with a descriptive memory and plan drawing, and belong to the Pompidou Center archive. Both drawing boards are signed by Frassinelli.

- Paulo Bandeira, Escola do Porto: Lado B, 1968-1978 (Uma História Oral) (Guimarães: A Oficina and Sistema Solar, 2014).

- Despite having an international reach from an early age, Mário Ramos says he doesn’t remember seeing any of these projects in the library of the School of Fine Arts where he was studying.

- The São Victor project (Barroso and Ramos, 1976) is deposited in the Drawing Matter archive (DMC 3478.2 and DMC 3478.1.1).

- Gian Piero Frassinelli and Antonio Natalini, Superstudio: La Moglie di Lot e la Coscienza di Zeno (Venice: La Biennale di Venezia, 1978).

- Gian Piero Frassinelli, ‘Superstudio, Finding the Horizon’, Drawing Matter, https://drawingmatter.org/superstudio-finding-the-horizon/ [accessed 21 December 2023].

- These drawings can be found in the Drawing Matter archive (DMC 3477.4.4.3).

- Already after this text was first written, at the beginning of 2024, it was reported in April that the announced 170km would be drastically reduced to less than 2.5km.

- John Imam, ‘Architects Dreaming of a Future With No Buildings’, New York Times, 16 February 2021, https://www.nytimes.com/2021/02/12/arts/design/superstudio-civa.html [accessed 12 April 2024].

Ivo Poças Martins is an architect, currently working on his PhD research at Lab2PT, in Escola da Arquitectura, Arte e Design da Universidade do Minho with a grant from FCT.