Schinkel: ‘Precisely Loose’

What light may Schinkel’s drawings shed on Building Information Modelling (BIM) practice?

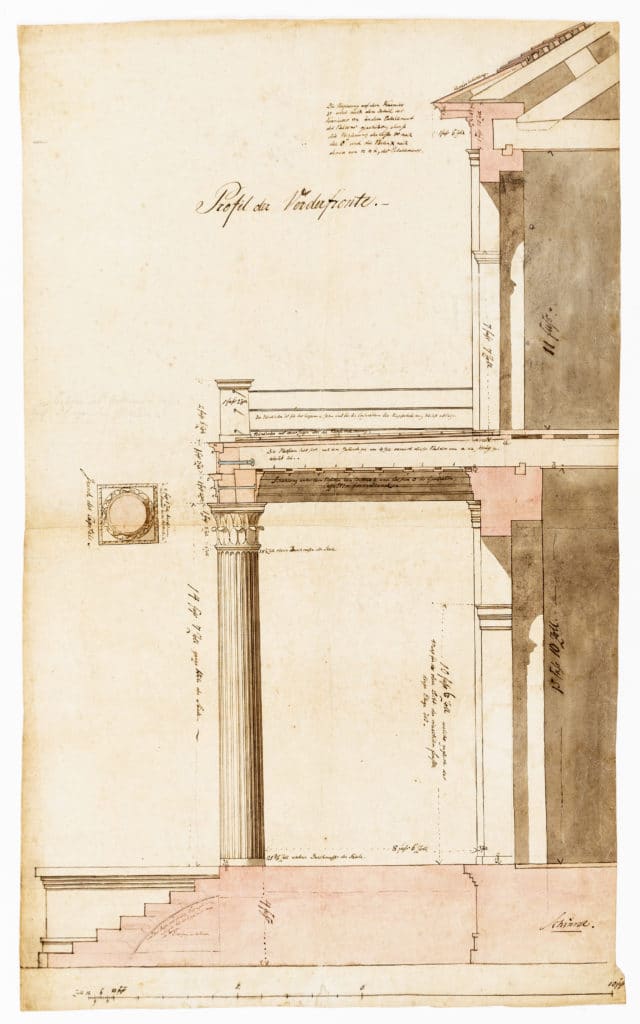

In 1806 the young Schinkel was asked to develop a residence design from a set of initial layout plans. He drew a façade section, a peristyle detail and a column capital, before the war began and the commission was discontinued. These development drawings demonstrate Schinkel’s ability, since his early years, to design across different scales with technical understandings. As we will see, in the age of Building Information Modelling (BIM) practice, Schinkel’s design method is highly relevant.

The drawings for Tilebein Country House at Züllchow in Pomerania, by Schinkel and his mason, Wimmel, are precise and, at the same time, rather loose. At the roof junction there is a gap between the lower and upper rafters, not necessarily drawn in scale. It suggests the correct load path of roof tiles, which shall bypass the periphery beam and transfer down to the lower rafter before reaching the tie-beam and the column, which stabilise the roof by lateral thrust. The gap articulates more than exact geometry: it conveys a structural intention, to be digested and understood by the builder. Similar examples can be found in other annotations to the drawing, such as ‘the beam of the building goes through [the column] and carries the [load of the] front roof [of the entrance]’, which was also a structural intention; ‘skylight in basement’; and ‘under the stairs, lighting maybe given at the sides’, of which the latter two are not drawn explicitly.

Compare Schinkel’s working method with that of contemporary BIM practice. BIM is designed to be developed in stages. The Level of Details (LOD) increases as the project moves on. Schinkel also developed his drawings in stages, but he understood construction details and was capable of moving back and forth between large and small scales during the early design stage. BIM is meant to be a virtual reality: it is modelled to be as accurate and informative as possible. Schinkel, instead of drawing everything in its exact shape, size, position and quantity, would draw intentions only – but very precise intentions.

Schinkel’s teacher, Friedrich Gilly, remarked that Schinkel would have a glimpse of ‘what was essential in an idea and what was not, and took the liberty to focus exclusively on the essential’ [1]. Gilly’s comment was originally made during Schinkel’s trip to Italy, where he collected ornament examples. Coming from Schinkel’s development drawings, we shall say, that exclusive focus on the essential intent in details also applies to his precisely-loose design method – something architects in the BIM age should be reminded of.

[1] Christoph Freiherr von Wolzogen, Report on Designs (Drawings) for the Tillebein Country House at Züllchow in Pomerania, 1806, p. 8.