Streetscapes: Bath

The following text is excerpted from Ptolemy Dean’s new book Streetscapes: Navigating Historic English Towns, published by Lund Humphries. Find out more about the book and purchase a copy here.

‘Bath is, beyond any question, the loveliest of English cities’, wrote Walter Ison, whose 1948 work on the city continued: ‘During the eighteenth and early parts of the nineteenth centuries Bath underwent a complete metamorphosis, a spontaneous and orderly process of rebuilding and extension, based on the classic ideal’.[1] Were [John] Speed to return to Bath, he would recognise very little from his map (click here to view an interactive version), apart from perhaps the outer walls of the abbey and the layout of one or two of its medieval streets. Indeed, the buildings of Bath now appear so uniformly 18th century that it can be difficult to decipher where the medieval town stops and starts.

And yet it is the medieval core, and especially the great Roman baths, that have always been its focus. The expansion of Bath by John Wood and his son into the surrounding landscape is justly celebrated. But less well known is how those new streets were then reconnected to the ancient core by Thomas Baldwin to create a unified and coherent city overall. It is this two-stage route from the Cross Bath at the heart of the medieval town to Queen Square and then on to the Circus and Royal Crescent that is the subject of this chapter. The ‘Crosse Bathe’ is illustrated and identified by the letter ‘W’ on Speed’s map, while the full route to the Royal Crescent appears on the 1886 OS map (click here to view an interactive version).

The origins of Bath were determined by its unique thermal waters, which are forced to the surface within a wide meander of the River Avon surrounded by steep hills. This boggy terrain might not have been the best location for a town, but the Dobunni, an indigenous Iron Age tribe, believed the hot springs were sacred and dedicated them to the goddess Sulis. The Romans, ever perceptive in the creation of towns, formed the walled settlement of Aquae Sulis—tactfully adopting the name of the local goddess. It was conveniently close to the Fosse Way, which ran between the legionary fortresses of Exeter and Lincoln, and became one of the most impressive bathing complexes in northern Europe. The Romans enclosed the bath and temple complex area within a tight enclosure of walls, and it is these walls, much rebuilt and with three main entrance gates, that are shown on Speed’s map.[2] Unusually, the gates do not face one another in all four directions in the Chichester or Exeter way, as the eastern side of the town was largely flanked by river. Consequentially, the north gate (marked ‘A’ on Speed’s map) is located at the north-east corner of the walled enclosure, with most of its northern edge solidly walled. This unusual arrangement would affect the later development of the city.

In time the Roman buildings collapsed and, as elsewhere, a new street plan emerged following a loose grid pattern anchored by the location of the Roman gates. Bath became an important ecclesiastical centre and, for a short period after 1088, the abbey church became a cathedral. The spa waters were controlled by the abbey, and the Cross Bath, constructed on the site of the Roman cistern and altar, was the most private and the most comfortable in temperature (marked ‘W’ on Speed’s map). By 1500, Bath Priory was in decay, and the old Norman cathedral was knocked down and replaced by a very much smaller priory church. Within barely a generation, however, the priory was dissolved, its roof stripped and the new church sold off. Eventually the city successfully petitioned Elizabeth I that it be restored as a single new Protestant parish church to replace five others. In 1574, the Queen visited Bath, beginning a process of royal patronage that would eventually transform the place. As Ison remarked, ‘This insignificant city, with little to recommend it beyond the medicinal springs and a charming situation, was chosen by the arbiters of fashion to be their summer retreat, and following in their wake came all of those possessed of rank or fortune . . .’.[3]

The astonishing 18th-century expansion of Bath is well described elsewhere. The architect John Wood declared in 1725:

I proposed to make a grand Place of Assembly, to be called the Royal Forum of Bath: another place, no less magnificent, for the exhibition of sports, to be called the Grand Circus; and a third place, of equal state to either of the former, for the practice of medicinal Exercises, to be called the Imperial Gymnasium of the city . . .[4]

The land chosen for this development was north and west of the medieval city, where the ground rose above the stuffy river basin below. Queen Square came first, completed in 1735, followed by the Circus and then the Royal Crescent (eventually completed by Wood’s son in 1775). But while these make a remarkable sequence of new streets, the connection back to the historic city remained unresolved. This was due, at least in part, to the solidly walled northern edge of the old city which had hindered access for development on this side. Furthermore, the land between Queen Square and the west gate of the old city had been developed by others who lacked Wood’s ambitious vision. The generosity of Wood’s streets around Queen Square contrasts with the relative meanness of those immediately to the south of it, as shown on the 1870 map.

In consequence, the Bath Improvement Act of 1789 was established ‘to effect some necessary clearance of the older part of the city and generally improve the approaches to the baths’.[5] Empowered by the Bath Corporation, the architect Thomas Baldwin drove the new Union Street through the medieval town, creating a new point of entry on its northern side, bypassing the narrow streets around the west gate and connecting directly into Stall Street, the medieval route south through the old town. This was widened, while Bath Street was driven west through more parts of the old town to reach the Cross Bath, which Baldwin also rebuilt. Stall Street was animated by an elegant arcaded crescent ‘for the honour and dignity of this City’.[6]

Bath remained a largely complete Georgian city until 1942, when it, like Exeter, became a victim of the Baedeker bombing raids. In 1968, Bath joined York, Chichester and Chester as the subjects for a government review on how to protect historic cities.[7] The architect Peter Smithson summarised the lessons of its success in 1971:

Firstly, Bath demonstrates above all that it is perfectly possible to build a memorable, beautiful, and cohesive community structure of fragments . . . Secondly, the use of the same materials controlled by substantially the same technology obviously helps. Thirdly, the art of town planning, as we see so clearly here, is to establish the measure and interval of events not to pre-determine form. That this is so observable so clearly in Bath can perhaps be attributed to the (probably unconscious) transfer of the theory of the Picturesque . . . from garden design to town design.[8]

Pevsner in 1958 had chosen to quote directly from Uvedale Price, who had written in 1781: ‘Intricacy . . . might be defined (as) that disposition of objects which by partial and uncertain concealment excites and nourishes curiosity . . . that most active principle of pleasure’.[9]

A closer look through Baldwin’s northern colonnade reveals how it screened the open area serving the west front of medieval Bath Abbey. The colonnade therefore ensured that the new symmetry created along the Stall Street frontage would remain unbroken and was able to mark the entrance to Bath Street without distraction. While managing the complexities of all of these pre-existing buildings and layouts was a remarkable achievement, the architectural consequence of Baldwin’s screen nevertheless conveys the inescapable reality that, in Bath, the abbey was secondary to the natural marvel of the thermal waters themselves.

As we move north, Baldwin’s Union Street cuts through the former city wall to connect into the southern end of Old Bond Street. The streets here are not aligned, but this is masked by an island building that masterfully manages the misalignment in a picturesque way – the pattern noted by Peter Smithson. In this view south along Old Bond Street, Union Street can be seen just to the left of the island building. The red-painted niche in this range accommodates a small figure salvaged from the Melfort Cross, a lost medieval structure that was close to the Cross Bath and which offers a subliminal link to the destination of this route.

A closer look at this small but vital island building reveals its modest form. The only composed elevation is the key northern end which fills the long view for those heading towards the medieval town. The royal coat of arms set into the lowered upper parapet on this side is enough to introduce skyline interest and reduce any hint of ‘boxiness’ on this aspect, which apart from the shop front is otherwise windowless. Elsewhere, where long views cannot be obtained, it mattered less and there is an irregular placing of windows, shop fronts and chimneys along its flank sides. The cross street behind, Upper Borough Walls, follows the line of the old north wall of the town, which had so constrained the town’s growth before Baldwin punctured it with Union Street.

Visible fragments of medieval Bath are rare to find, but a short stretch of the once containing north wall has somehow survived along Upper Borough Walls just to the west of where the new Union Street was cut through. Overshadowed by 18th-century redevelopment, it gives a vivid impression of the radical transformation of Bath at that time.

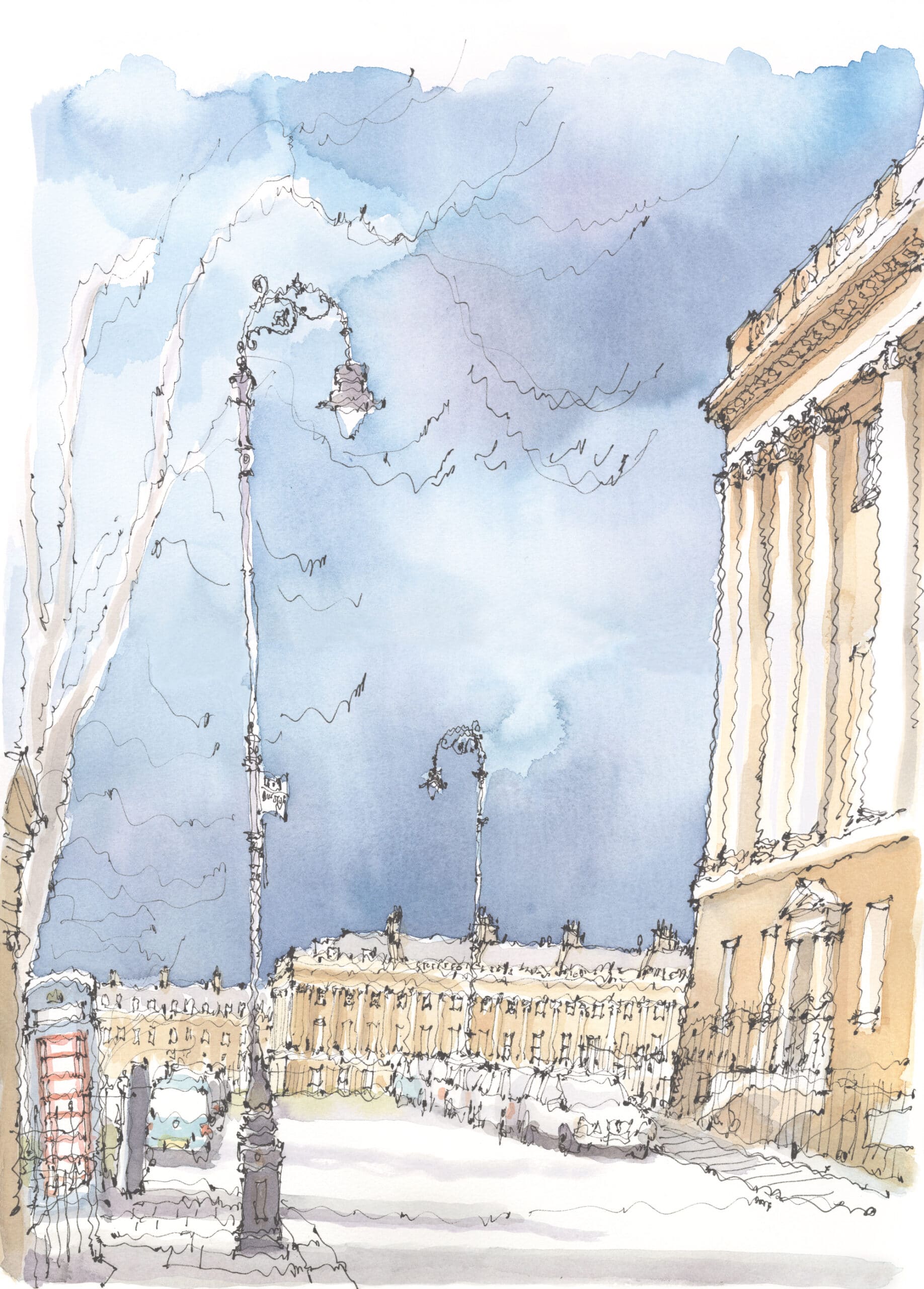

As we continue northwards, this view looks across from Old Bond Street towards Queen Square. It is the final connection between the historic centre, with the improvements made by Baldwin and the new streets added by Wood. This last section took decades to resolve. Initially the route from Old Bond Street to Queen Square passed along the appropriately named Quiet Street, which was initially a narrow road that was less than half of the width of Wood Street, which connected into Queen Square beyond. Quiet Street had to wait until 1871 before it was finally widened and, consequently, the richly articulated north side (seen on the right) strikes a decidedly Victorian character. The stagger of Quiet and Wood Streets seen in this view opens onto the trees of Queen Square beyond, marking an appropriately stately connection between the older and newer sections of Bath.

Queen Square was the first significant intervention made outside the walls of the old city by John Wood the Elder in 1728–35. Wood had initially intended to level the sloping site so that his new square could lie flat. But this would have cost an additional £4000 (a significant sum at that time), so he was forced to build in conformity with the natural fall of the land. This has affected how the square reads as a place. Wood envisaged the pedimented north side as a palace forecourt, which it achieves successfully largely because this side of the square runs level across the slope, looking down on what lies below. The east and west sides face the sloping land and consequently appear transitional and therefore seem to command less attention. Originally, the central garden of the square was formally laid out with a tall stone obelisk at its centre. The obelisk remains (extreme left) but trees planted in later years along the garden perimeter have grown so thickly that they now screen much of the central garden. Welcome though trees often are, the scale of the square is now hard to read, even in winter when the branches are bare. A proposal to remove them and to restore the formal arrangement of the square was mooted in 1946 but not carried through. Gay Street (right) continues up the hill to serve the further developments to the north. At the very far end of Gay Street, another clump of trees can already be seen.

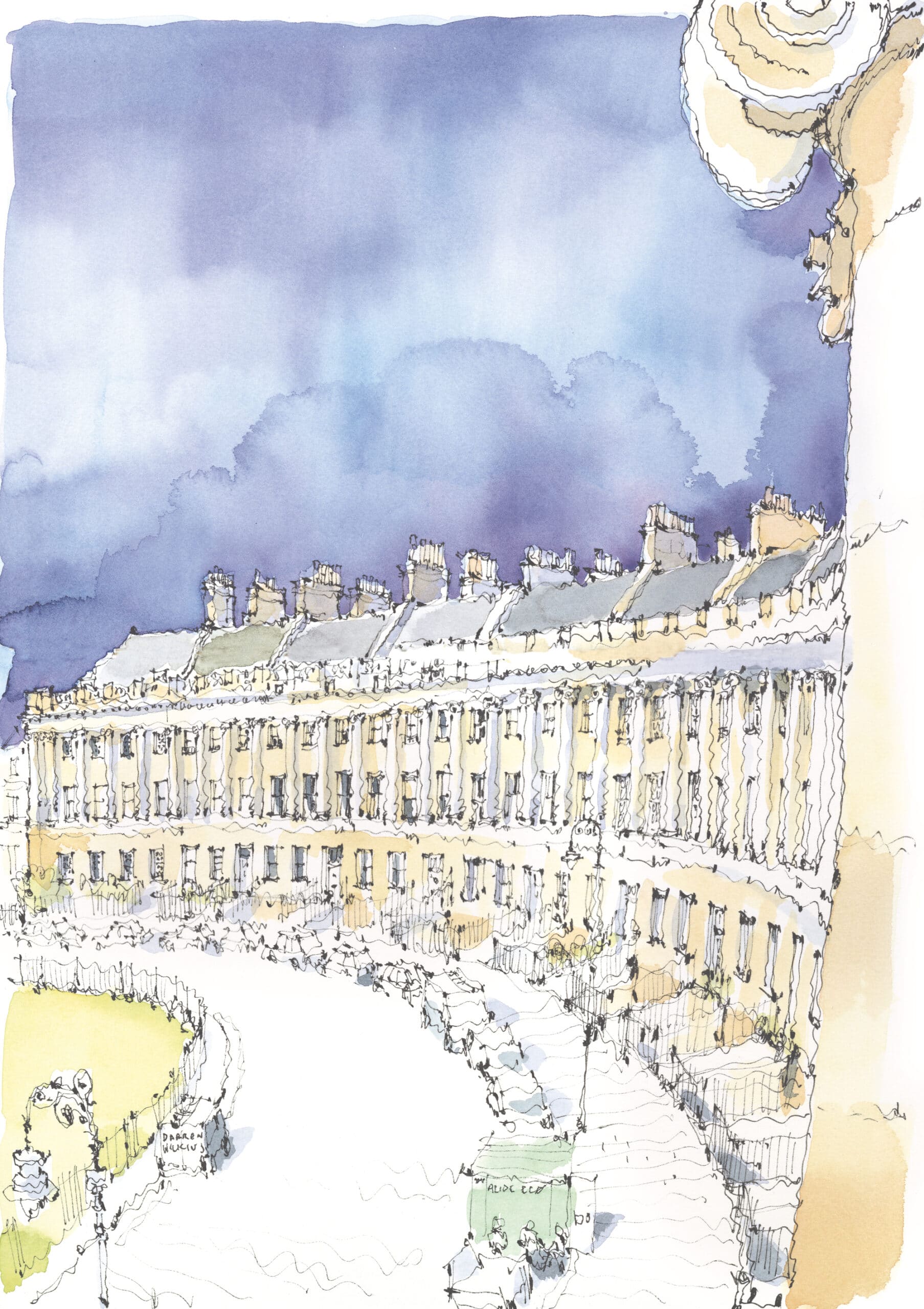

At the northern end of Gay Street, the Circus begins to open out. Here the slope of the long upward incline flattens and the ground again becomes level. Consequently, emerging onto the plateau of the Circus from the hill of Gay Street provides a palpable sense of arrival that is missing from Queen Square. Wood’s ‘Roman amphitheatre’ of 33 houses was originally hard-paved with a statue at its centre. There are now five immense plane trees, which could be seen in the distance from Queen Square. They form a group in the middle of what is now a grassed enclosure. Happily, there are no trees around the perimeter of the garden, so the composition of this remarkable space can be appreciated. As the three street entrances into the Circus are not aligned with each other, a change of direction is unavoidable. This configuration was deliberately achieved to manage a further extension of development to the north-west but without compromising the symmetry of the Circus. In the middle distance is Brock Street, the continuation of this route.

John Wood the Younger (born 1728) succeeded his father, who had died aged 50 shortly after the foundation stone of the Circus had been laid. The younger Wood extended the two streets out from the Circus. Brock Street, leading north-westwards, initially follows the contour of the hillside and appears near level, with an informal mix of well-mannered Georgian houses of the usual Bath pattern. It cleverly manages an architectural moment of calm to distinguish it from the palatial architecture of the Circus, whose houses are fully colonnaded, and what is to follow. In the distance, at the end of Brock Street, a row of buildings can be seen that are set well back behind further open ground – the only hint at this stage that the Royal Crescent lies ahead.

John Wood the Younger died in 1782, aged 54, having completed the Royal Crescent (1767–75). It is the summit of the Palladian achievement in Bath. The central house, now a hotel, affords a closer glimpse of the remarkable scale and generosity of these buildings from within. Wood designed the elevations but allowed the sub-lease of sites to prospective tenants, giving them full liberty to plan the interiors of the individual houses. Consequently, the backs of these houses are varied to the individual tastes of their owners. As a pattern of development, it has never been bettered.

Notes

- W. Ison, The Georgian Buildings of Bath from 1700 to 1830 (Bath: Kingsmead Reprints, 1948 [repr. 1969]), 27–9.

- Speed’s map is likely to be based on Henry Sabine’s map of 1603. See C. Spence, The Story of Bath (Stroud: The History Press, 2016), 71.

- Ison, The Georgian Buildings of Bath, 29.

- John Wood, quoted in ibid., 31.

- Ison, The Georgian Buildings of Bath, 168.

- ibid.

- ‘Bath – A Study in Conservation’ was written by Colin Buchanan and Partners. It was the least successful of the four reports, leading to much unnecessary demolition, recorded in A. Ferguson, The Sack of Bath: A Record and an Indictment (Salisbury: Compton Russell Ltd, 1973).

- P. Smithson, Bath –Walks within the Walls (Bath: Adams & Dart, 1971). I am grateful to Niall Hobhouse for giving a copy of this to me.

- Uvedale Price, ‘Three Essays in the Picturesque’ (1781) quoted in N. Pevsner, North Somerset and Bristol: The Buildings of England (Harmondsworth: Penguin Books, 1958), 95.

Ptolemy Hugo Dean OBE is a British architect, television presenter and the 19th Surveyor of the Fabric of Westminster Abbey. He will be known to some as a historic buildings adviser on the BBC 2 ‘Restoration’ series. Previous books include Sir John Soane and London and Sir John Soane and the Country Estate (both with Lund Humphries).

Peter Smithson’s commentary on the city, referred to in this text, can be viewed as an interactive PDF, here. Find here a short video by Ptolemy Dean on the book, made for the Architecture Foundation’s Book Week 2024.

– Timothy Hyde