The Future of the Past: The ‘Round Church’, Cambridge

The war to restore to churches ritual and at the same time architectural dignity was waged by one man and one society, the man being a fervent convert to Catholicism, the society calling itself Catholic too, but meaning what is called Anglo-Catholic. They operated independently, but appreciated one another. The man was Augustus Welby Northmore Pugin (1812–52)[1], the society was the Cambridge Camden Society.[2] Pugin began to write and fight in 1835, and his most important books came out in 1841 and 1843; the Cambridge Camden Society was founded in 1839 by the Cambridge undergraduates, John Mason Neale and Benjamin Webb, and its journal, the Ecclesiologist, started to appear in 1841. Pugin’s writings were highly successful, though in some quarters his success was a succès de scandale; the same was true of the Camdenians together created the High Victorian attitude to church buildings—High Church buildings—and that implied church restoration.

Pugin on Wyatt is as good as Carter and Milner on Wyatt. ‘All that is vile, cunning and rascally is included in the term Wyatt.’[3] Pugin on church building, however, is new: ‘We can never successfully deviate one tittle from the spirit and principles of pointed architecture. We must rest content to follow, not to lead.’[4] But the Catholic architecture of the ages before the Reformation which was to be followed might have been Early Christian, Romanesque (i.e. in England, Norman), Early English with a lancet windows, the style of Westminster Abbey, Decorated or Perpendicular. Commissioners’ churches were usually lancet style or, if elaborate, Perpendicular. Pugin from 1839 or 1840 onwards regarded as the climax of English church architecture the style of Westminster Abbey, that is what he called Second Pointed or Middle Pointed. The Ecclesiologists concurred.

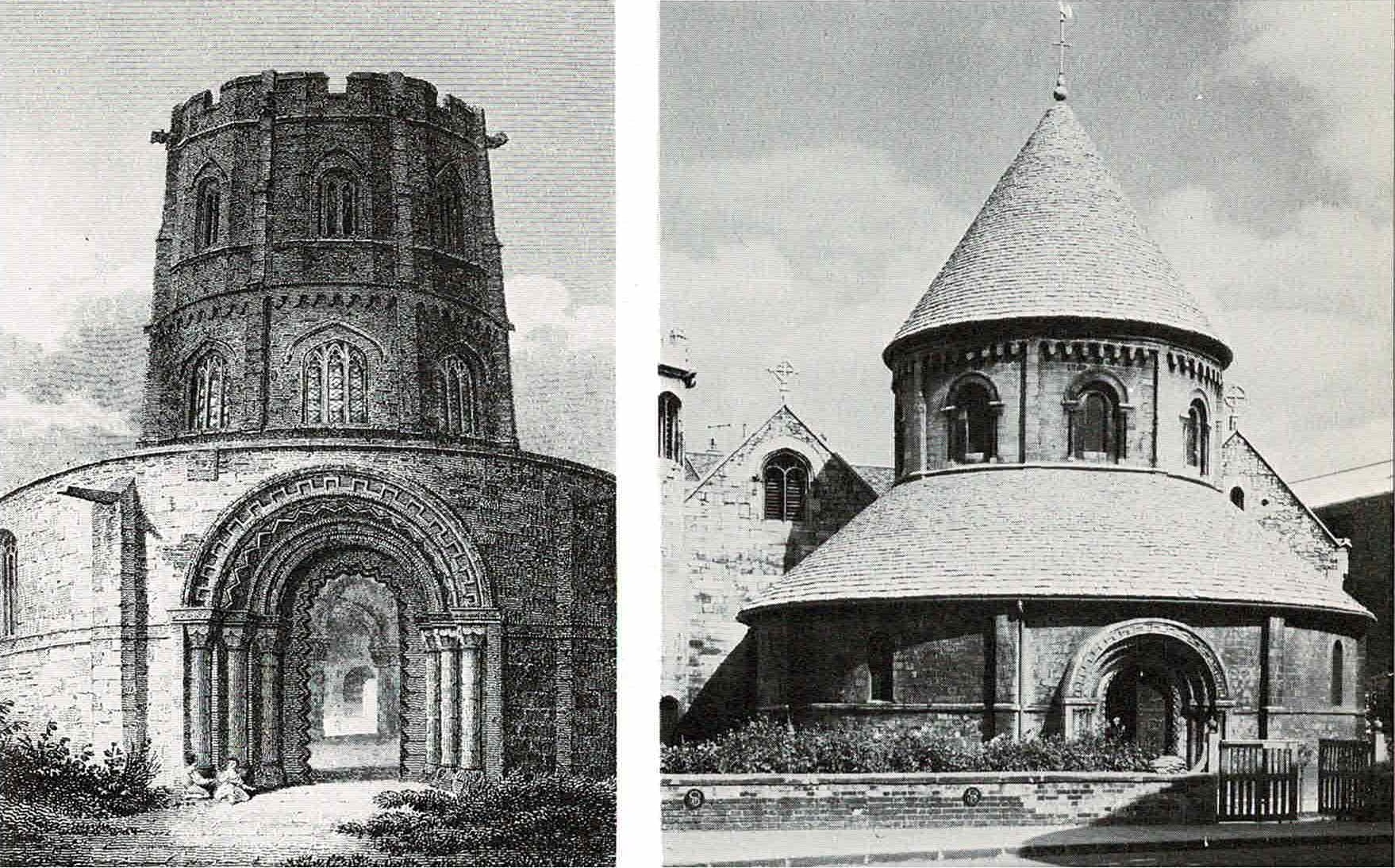

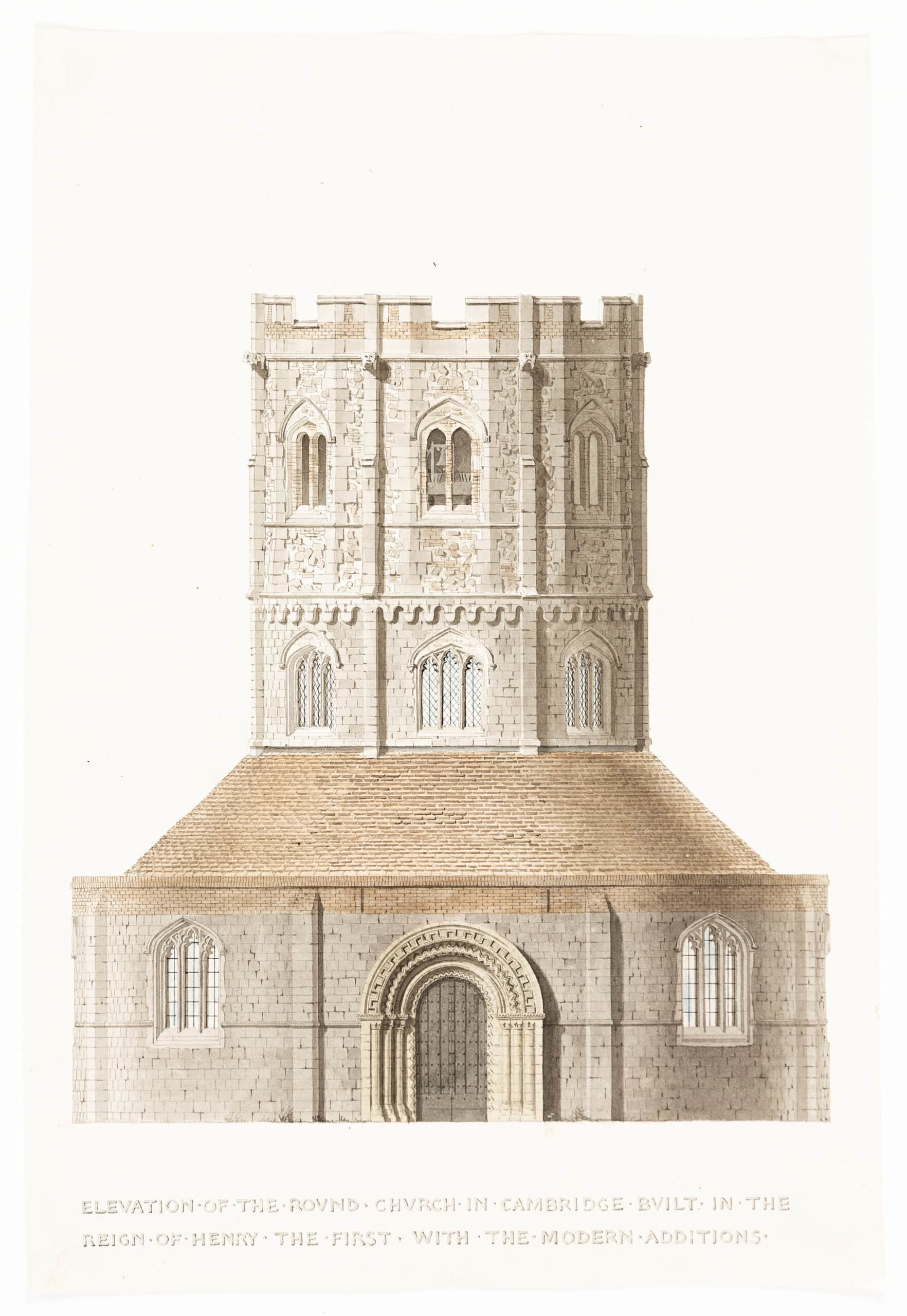

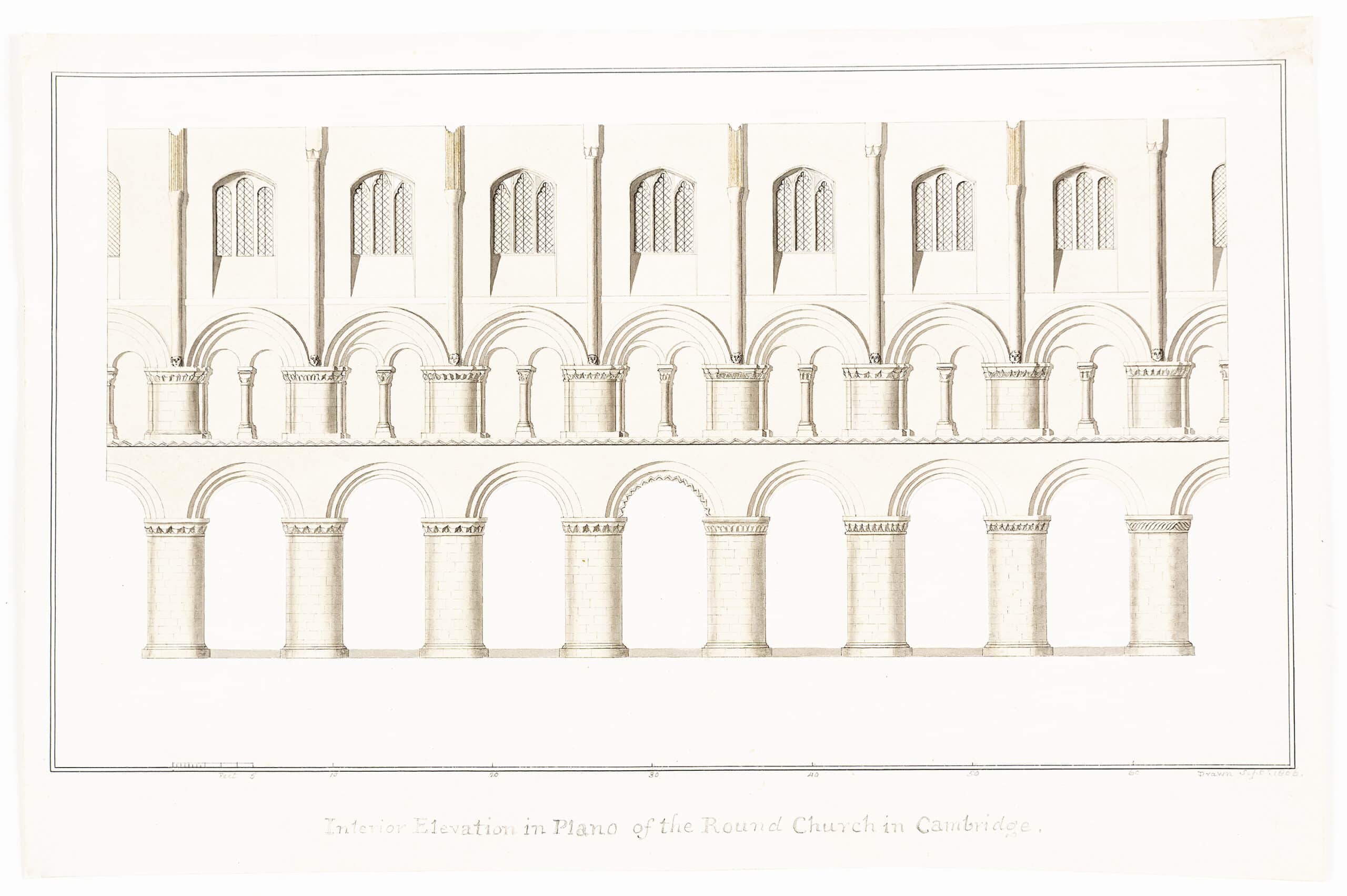

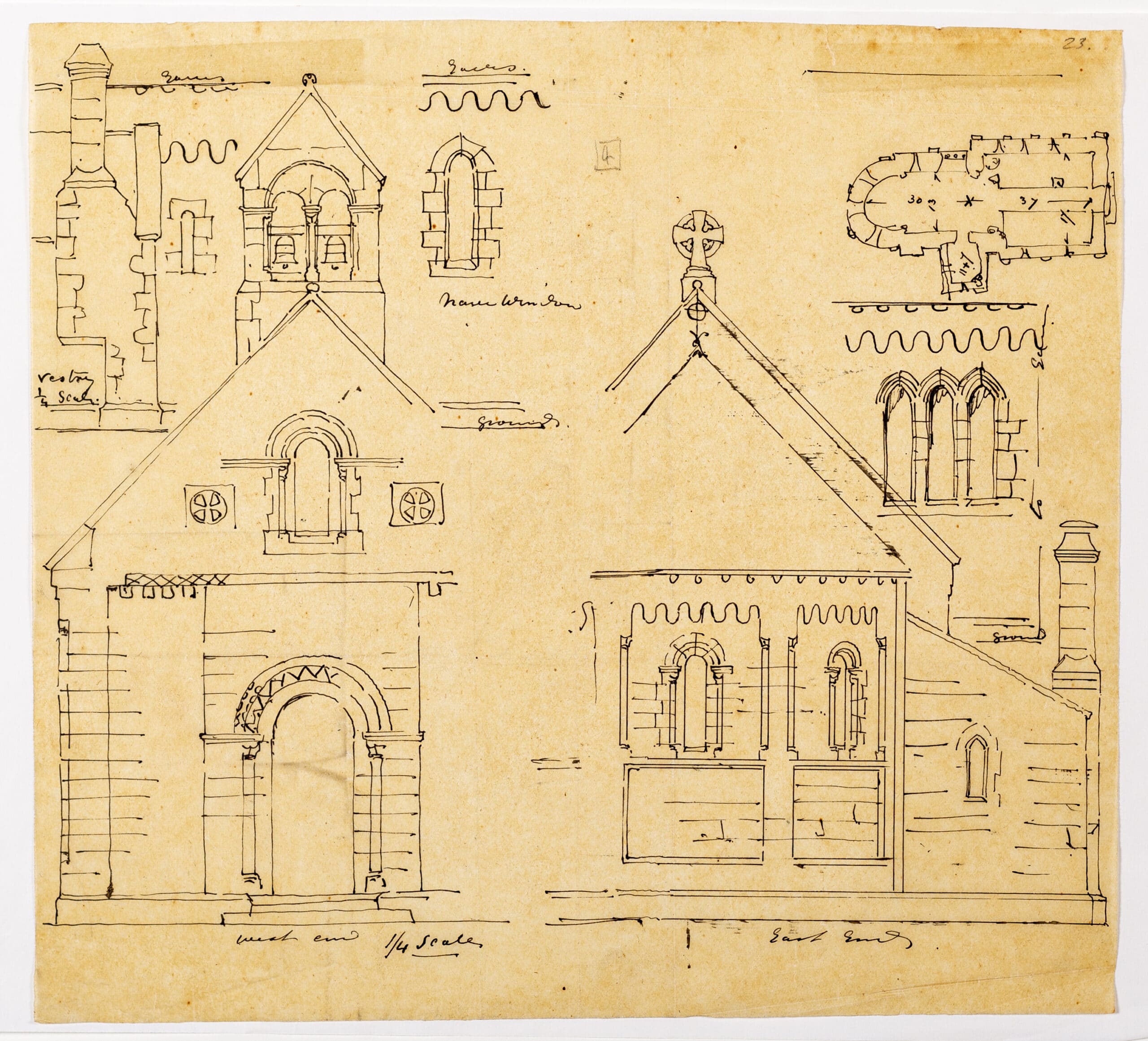

Pugin and the Ecclesiologists were also agreed on certain ritual requirements: a sufficiently long chancel for the altar and a surpliced choir, the isolation of chancel from nave by a screen, i.e. of priest from congregation, and more generally on dignity and sacramentality. In Pugin’s writings restoration appears only marginally; Neale and Webb not only dedicated space to it in the Ecclesiologist, but went themselves into the promotion of restoration. It was they who induced Salvin to restore the Round Church, i.e. the Norman Church of the Holy Sepulchre, in Cambridge. The way the restoration was done gives a foretaste of their attitude. The Perpendicular ambulatory windows were preplaced by Norman windows and the bell-turret was removed and a conical roof was built instead. The procedure followed the declared principle of the Camdenians. In the Ecclesiologist of 1842 we can read: ‘To restore is to revive the original appearance … lost by decay, accident or ill-judged alteration.’[5] And the principle was applied with zest; for as Neale said: ‘How can I feel the most devoted affection to so noble a cause as that of church restoration?’[6] Already, in the first volumes of the Ecclesiologist, the Camdenian was set out in unambiguous detail:

We must, whether from existing evidences or from supposition, recover the original scheme of the edifice as conceived by the first builder, or as begun by him and developed by his immediate successors; or, on the other hand, must retain the additions or alterations of subsequent ages, repairing them when needing it, or even carrying out perhaps more fully the idea which dictated them…. For our own part we decidedly choose the former; always however remembering that it is of great importance to take into account the age and purity of the later work, the occasion for its addition, its adaptation to its users, and its intrinsic advantages of convenience.[7]

There are ominous turns of phrase in this: ‘carrying out more fully’, ‘taking into account the purity of the later work’, ‘intrinsic advantages of convenience’. The first may mean making a church more Second Pointed than ever it had been, the second the removal of Perpendicular additions, the third the alteration of internal fixtures for the sake of Victorian worship. Indeed a little later Ecclesiologist says: ‘We have no hesitation in urging the propriety of entirely removing later super-added clerestories, and restoring the roofs to the form they undoubtedly had when the earlier arcades of the nave were built’[8] and expressed the hope than in a particular case the architect ‘will not hesitate to replace the existing late Middle Pointed tracery of the east window with a design of an earlier character, so as to restore it to the state in which it must have been originally erected.’[9]

Excerpted from Nikolaus Pevsner, ‘Scrape and Anti-Scrape’ in The Future of the Past: Attitudes to Conservation 1174–1974, ed. by Jane Fawcett (London: Thames and Hudson, 1976), 40–42.

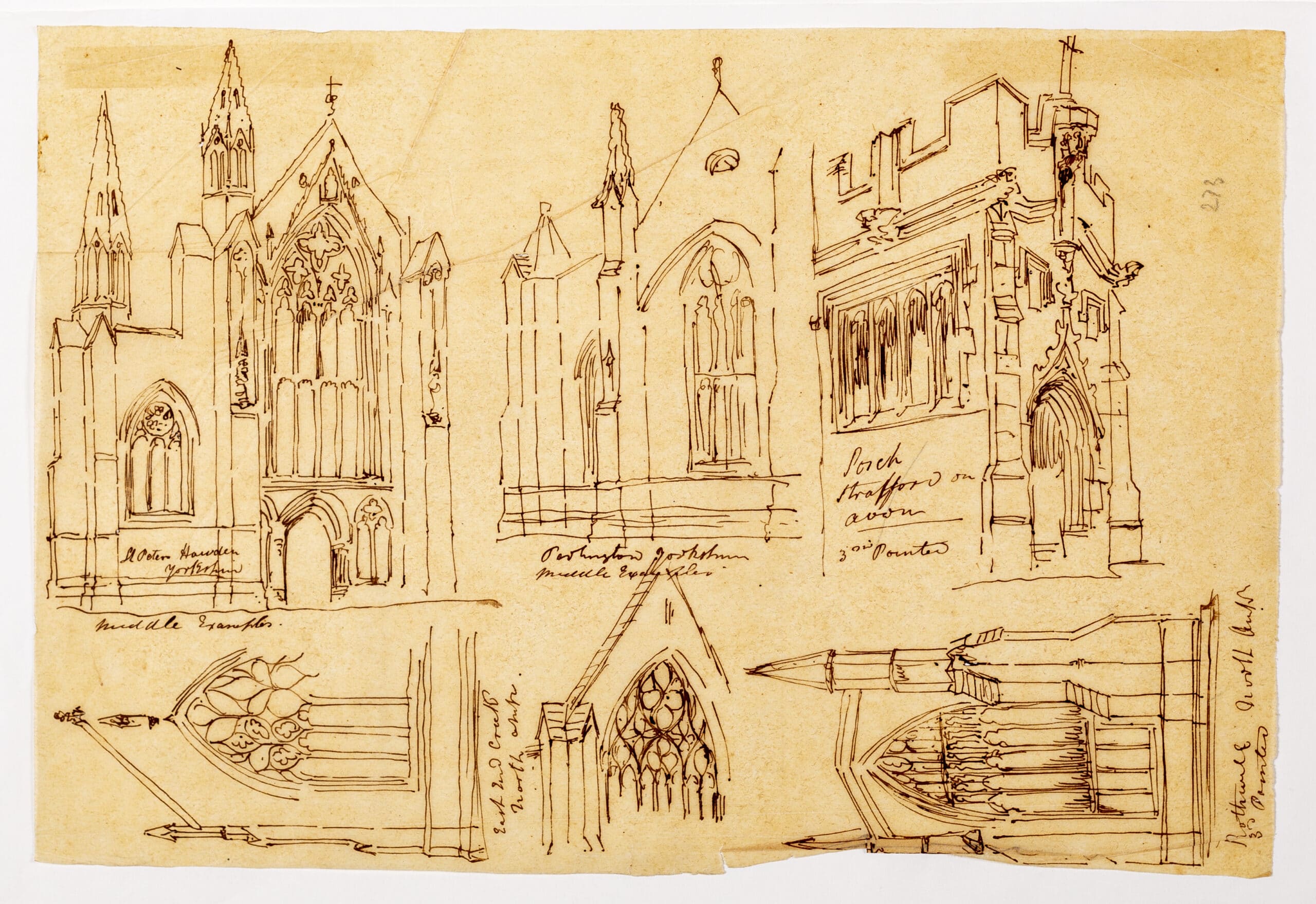

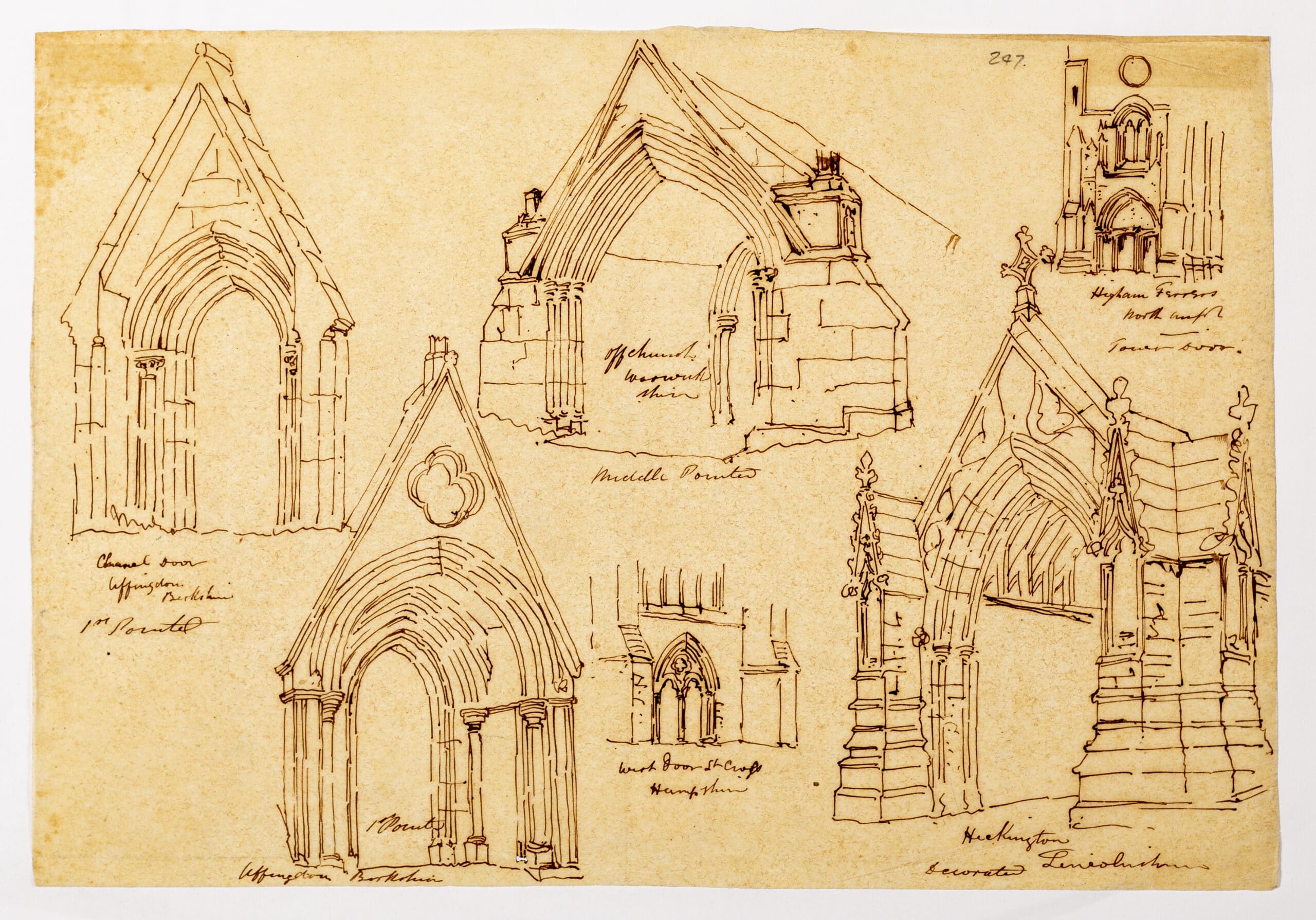

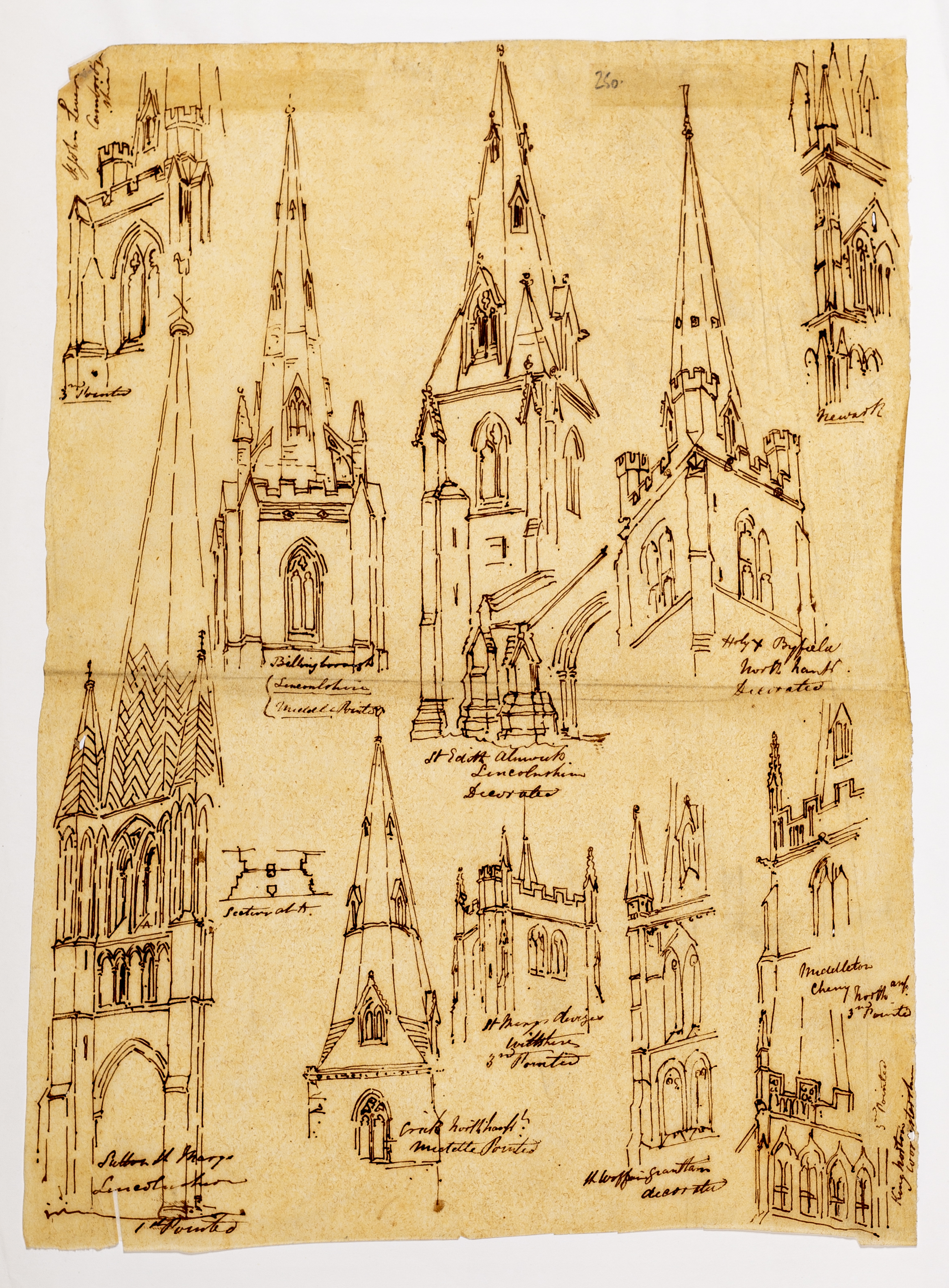

From the Drawing Matter Collection: William Wilkins’ surveys of the Round Church before the Camdenian ‘restoration’ by Salvin; studies of ecclesiastical subjects by Salvin from an album of nearly 600 record, survey and restoration drawings.

Notes

- B. Ferrey, Recollections of A. C. Pugin and A. W. N. Pugin (London, 1861); M. Trappes Lomax, Pugin. A Medieval Victorian (London, 1932); D. Gwynne, Lord Shewsbury, Pugin and the Catholic Revival (London, 1946); S. Gordon Clark, ‘A. W. N. Pugin’, in Victorian Architecture, ed. P. Ferriday (London, 1963). P. Stantons’s excellent Pugin (London, 1972) came out after I had delivered my lecture and transformed it into this paper.

- J. F. White, The Cambridge Movement (Cambridge, 1962), especially 156ff.

- B. Ferrey, op. cit, 156.

- A. W. N. Pugin, The True Principles of Pointed or Christian Architecture (London, 1841), 9.

- Ecclesiologist, I, 1842, 70.

- J. F. White, op. cit., 158.

- Ecclesiologist, I, 1842, 65.

- Ibid., IV, 1845, 104.

- Ibid., V, 1846, 77.

– Tom Spalding