Aitchison / Prendergast

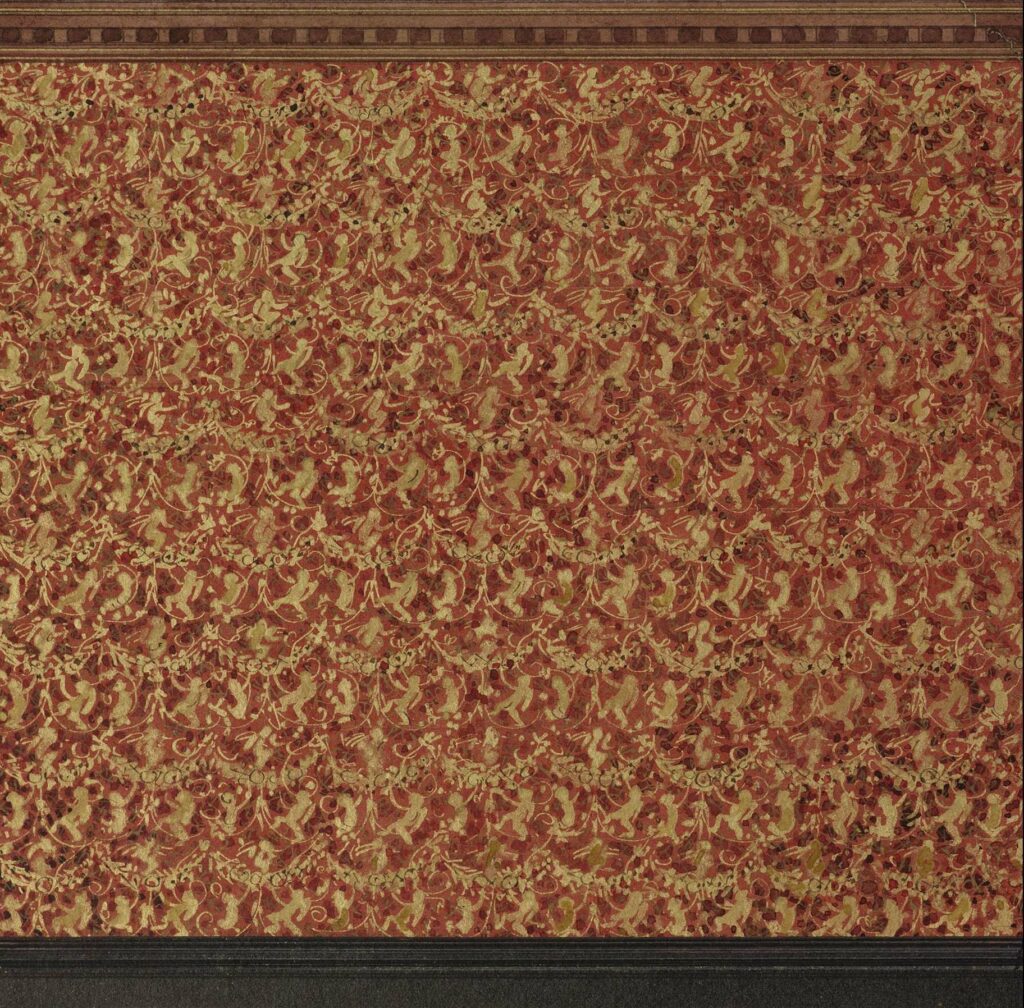

This finely detailed watercolour drawing is a perfect miniature representation by George Aitchison of his proposal for the composition of a wall in the morning room of Lord Leconfield’s house in Chesterfield Gardens, London, 1881. The figures that define the room – the door and its frame, the fireplace and its altar-like structure containing a mysteriously blank mirror – are all drawn with care, but also with a cartoon-like character expressed in a parody of hardwood veneer and the simplicity of the dark skirting that connects them together. Each one of these is instantly recognisable as an object belonging to the domestic interior. Along with the section lines that frame the drawing, tracing round the frieze at the top and the matching furniture at its edges, these elements mark the boundaries of a strange forested domain of tangled lines.

Read as part of the same language as the emblematic door and fireplace, this field clearly represents an expanse of scaled-down stencil work that proliferates over and around the walls and the chimney breast. If, however, we take into account the fact that ‘The field may be Farmer Hodges’ but the landscape belongs to him who appreciates it,’ which Aitchison quoted at the start of his book The Principles of Restoration (1877) then it is equally apparent that it is not necessarily what it seems.

Aitchison was a man with a well-rounded public life, belonging to an artistic milieu centred on his friend Frederick Leighton; he was a founding member of SPAB and a professor at the Royal Academy, becoming president of the RIBA in 1896. If he painted this complex and repetitive field, which he probably did, it would have taken many hours of private time to complete. Moments of reverie and boredom can be detected in the movements of the tiny men who strut, squat, dance and recline amongst the many layers of golden bower. Sometimes they are squashed up together or conversing in pairs, at others they are quite separate and their little heads are barely visible through the branches. The ground upon which they are laid is a beautiful, archaeological red, but over the top is a speckling of deeper blots like old blood that follow no pattern. The drawing is trapped in a separate world defined by its section line and made more evident by the empty mirror that reflects nothing and which may, in fact, be a window into purgatory.

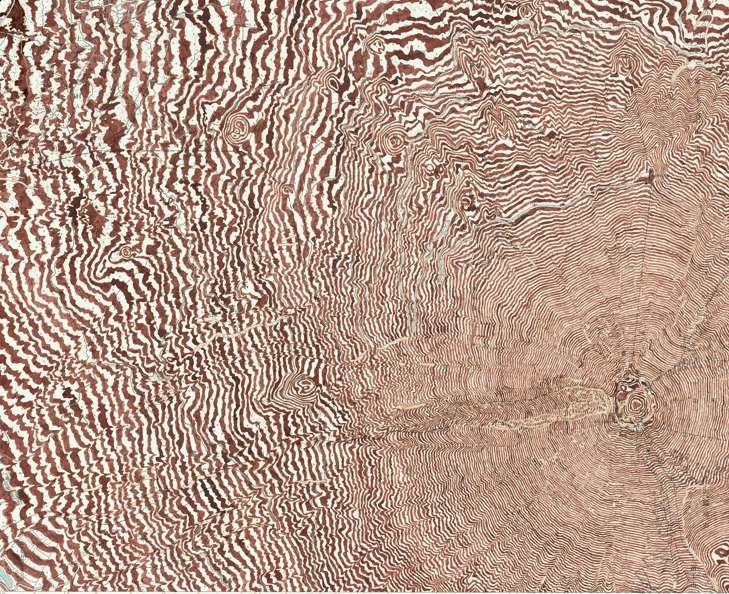

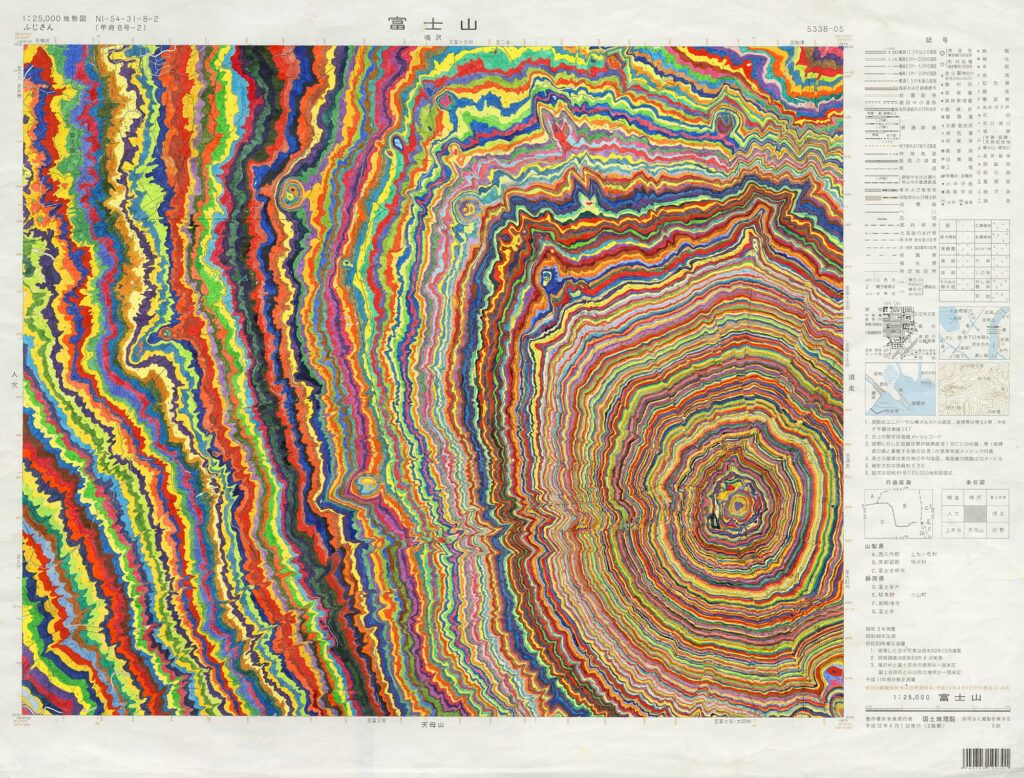

In her book Memoirs of a Survivor (1974) Doris Lessing uses the decorated field (this time created with wallpaper) as an imaginative device to suggest worlds beyond reality, in which the problems that beset life can be lived through differently, as in a dream. A connection between the drawings of Aitchison and the writing of Lessing was first made in conversation by the artist Kathy Prendergast while looking at the Aitchison drawings in the RIBA Study Room. As she examined the drawing of the wall in the morning room of Chesterfield Gardens with a magnifying glass, trying to work out how the structure of the pattern was laid out, and whether it was painted entirely by hand or aided by some mechanical means (she decided against this), she talked about making her own drawings. Her process of rendering very fine repetitive strokes, particularly in her earlier drawings of the world’s cities, often induces the disembodied state of mind evident in Aitchison’s wallpaper. The drawing entitled Mount Fuji, shown here, enacts this process in ink over a printed map, and so the asymmetry of the framing of this smoothly sloping land surface that is nevertheless replete with turmoils and quivering fragilities is predetermined. Made as part of a series called The Land Describes Itself, this was a precursor, using just one colour, to the second Prendergast drawing shown here called Fujidelic.

For Prendergast, the fascination of these images is the ambiguity of the surface, which only works as a drawing when it becomes extremely flat: in the way that the surface of absolutely still water is flat – a flatness that has tension, like the Black Square of Malevich. When this is achieved another dimension – the sky or the world under the surface – is implied but not seen. This, for her, was the link to Lessing’s wallpaper, which can have its figurative and associative moments: a zebra’s hide, a nipple, a blemished stone, or even a pattern; but the ultimate effect of the overlaid drawing is utterly transformative, and these images are trapped in the thinnest of layers.

– Iris Moon