To Table

To table is to create the conditions for collective presence through food, space, event, and ritual; it is to host a gathering where practices and events—ranging from the everyday to the ceremonial, the spontaneous to the planned—become acts of social meaning-making. Also, as a verb, ‘to table’ conventionally carries a dual meaning, depending on its context and origin: it can either introduce an issue for discussion or postpone it. This linguistic duality reflects the table’s inherent role in both presentation and withholding. [1] As a noun, table has two primary meanings, too. On the one hand, it is a horizontal surface for eating, gathering, working, or displaying objects and on the other hand, it is an abstract chart that organises information in rows and columns for analysis and communication. In both cases, its essence lies in the systematic organisation, an ordered placement of components that clarifies relationships and establishes perception. Whether physical or conceptual, a table imposes order upon disorder so that meaning can be read.

Making a diagram of a table arrangement is a way of depicting a structure that describes and regulates both spatial and social relationships. Diagrammatic consistency is what allows the same configuration to remain relevant across different scenarios and contexts. This is not a matter of the type of the table in the everyday sense, not a classification by function or by material, but of the forms of interaction supported by the very configuration of the table. A table may vary in materiality or function while being described by the same diagram. A U‑shaped table, for instance, can serve equally well for a ceremonial feast or a business meeting. The physical form gives scale to the diagram and defines the conditions for collective interaction. This scale is constrained by intrinsic qualities of the event, namely the format, the purpose of the gathering, and the number of participants involved, and by surrounding factors like spatial characteristics of the room, physical boundaries, and so on. The two sets of parameters mutually determine the limit of the table and the scale of its diagram. Choosing a particular table, or essentially a particular diagram and scale, means choosing a way of social organisation—and, in doing so, delineating what the group at the table is.

In Politics, Aristotle introduces the concept of measure (μέτρον) as a limiting scale that preserves the integrity of the community. Visual comprehensibility, audibility, and recognition form the sensory thresholds by which the community’s proper scale is determined. A polis must be of such a size that it can be grasped in a single view, where the herald’s voice carries to all, and each citizen is recognised through their conduct and civic presence. The same principle applies to the table. The very act of gathering around a table fosters a sense of belonging, reinforces cohesion, and affirms a collective identity. Yet once the table is not limited and becomes too large, almost infinite, like a ‘flowing water banquet,’ the integrity of the collective experience begins to erode. The table no longer unites, but fragments the community into multiple self‑contained groups; it effectively splits into modules, each functioning as a group within the group. Despite such disintegration, the diagram of the table still holds everything together, allowing the composition to be perceived as a whole, even if no longer experienced as such.

We can see the diagram of the table operating as an architectural diagram: it constructs axes, central points, grids, proportional systems, etc.[2] It is not a different diagram, but one with the same compositional logic applied at a different scale. Even when such a diagram appears to be neutral, it already encodes hierarchies, centres and peripheries, lines of symmetry and intersection, that begin to carry extended meanings, including signals of power dynamics (accents and dominants). The very principles of social interaction presuppose hierarchies. They are always present, even in subtle gradations of visibility, proximity, influence, or simply through differentiated levels of participation, from main actors to supporting roles.

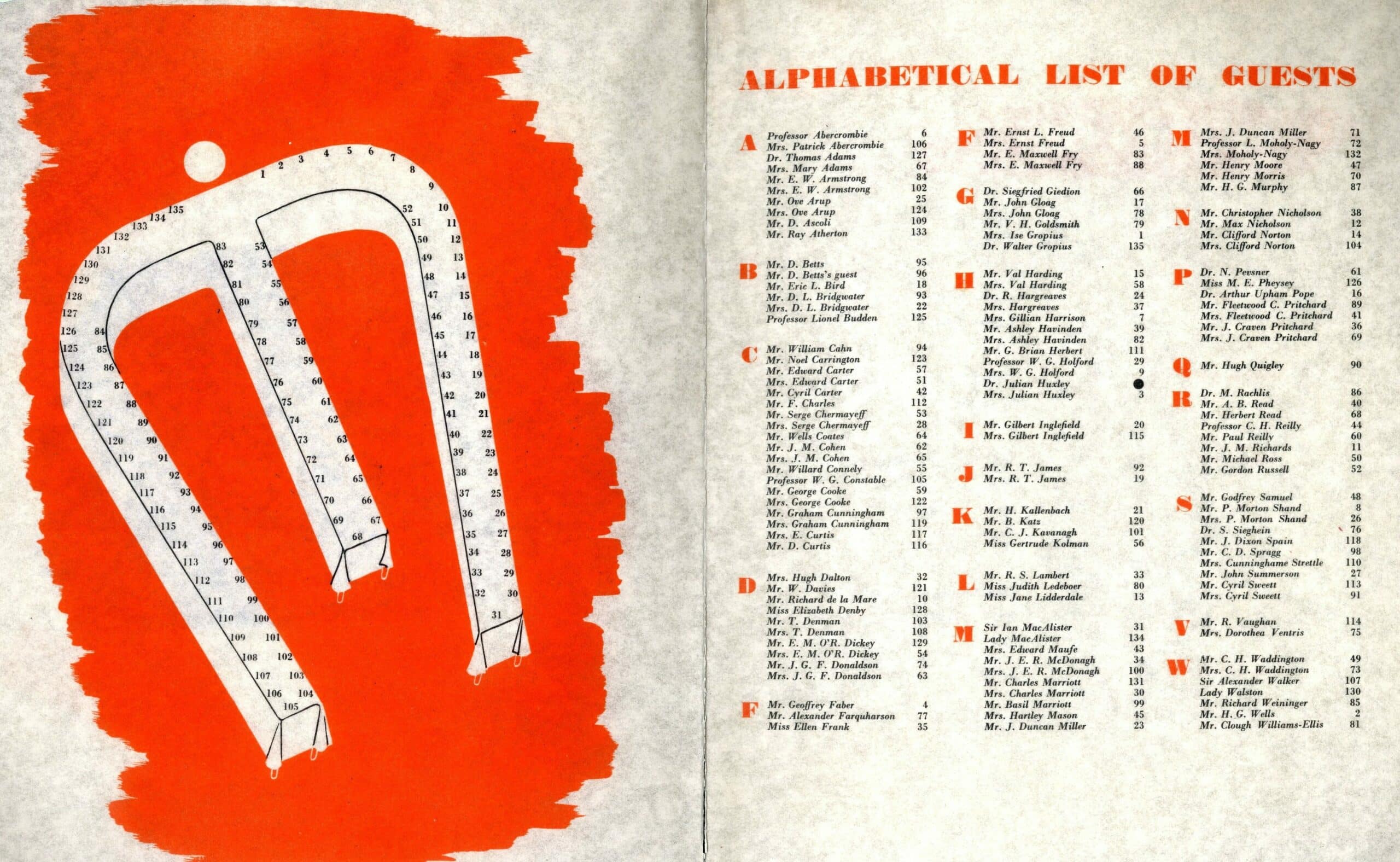

During an event, the spatial and social logic of it—which are not mere reflections of one another but overlapping manifestations of a single diagrammatic order—is made explicit in supplementary visualisations such as a seating chart. As an abstract yet purposeful diagram that applies to certain events, the chart translates social structures into spatial hierarchies by pointing out the position of characters. In the Bill of Fare, a foldable menu card designed by Laszlo Moholy-Nagy for Walter Gropius’ farewell dinner held on the occasion of his leaving England for Harvard University in 1937, there is a seating chart of 136 guests. At its centre, above the turned E‑ (or W‑ or M‑) shaped table, a bold dot draws attention: both a graphic anchor and a symbolic ‘head of the table.’[3] Intriguingly, that seat was not assigned to the celebrant himself, but to the eminent biologist Dr Julian Huxley, who chaired the dinner and delivered the toasts. Gropius was seated immediately to his right hand (seat 135), with Mrs Ise Gropius to his left hand (seat 1).

The ‘head of the table’ refers to the most important seat, usually occupied by the highest-ranking figure: the host, the leader, an authority, a guest of honour, or newlyweds. The ‘head’ is not just a linguistic or social convention, but a spatial designation produced by the composition and held by the diagram.[4] The most common configuration is placement at the short, terminal side of the table, as in Tim Burton’s 1989 Batman, in which Bruce Wayne and Vicki Vale sit at opposite ends of an absurdly long table—a staging that turns a private meal into a performance of awkward formality. In contrast, in Leonardo da Vinci’s The Last Supper, one of the most iconic tables in art history, the central figure is positioned at the middle of the long side, with the others unfolding symmetrically on either side in a composition that implies strong symbolic and religious connotations.

Although the tables are more or less the same and have the same diagram, the two examples convey different meanings. Placement at the short end makes the figure more visible to potential participants at the table and marks a position of authority and exclusivity—especially since it is typically reserved for one person. Centrality along the long axis, by contrast, reinforces unity, particularly when the group is positioned on one side of the table, making the composition observable to others while still emphasising the significance of the central figure. By only shifting who sits where, especially the ‘head’, the two tables produce very different relationships, while still following and extending the internal logic suggested by the table and its diagram.

The arrangement at the table encodes cultural meanings that are grasped both consciously and unconsciously. In this sense, the table becomes a site of symbolic order. Seating configurations and role assignments, structured by status, gender, or age, reflect cultural constructs shaped by etiquette, protocol, tradition, and religion. These patterns, if not established conventions embedded in collective memory, are practised and continuously reproduced and reinforced through images, photographs, films, and texts. By repetition, they become planted in our perception, forming a visual canon through which we intuitively read any table scene as one organised by power relations and social hierarchies. Even small shifts in the formal characteristics of the table set, such as an additional chair, can significantly alter the interpretation of the table and its diagram, and hence the group dynamics it implies.

Within this framework, the table, whether part of a ritual or used as a compositional device, is understood through cultural codes, often by analogy. Take, for example, the ubiquitous round table: a configuration that intuitively evokes the legend of King Arthur, it signifies unity and shared authority, even if such equality is more symbolic than actual.[5] Similarly, The Last Supper continues to shape visual culture far beyond religious contexts, with its compositional logic cited in both homage and subversion. Among many interpretations, Luis Buñuel’s Viridiana (1961) and Annie Leibovitz’s photo shoot for The Sopranos (1999) stand out. Both replicate the formal structure and the implied hierarchy of Leonardo’s work, but radically shift the context—transforming its religious solemnity into scenes charged with irony, power dynamics, and secular meaning. The sacred is replaced with the profane, yet the diagram remains intact, playing a central role in the adaptation: it preserves and transmits visual conventions, creating a sense of recognition and connection for the viewer.

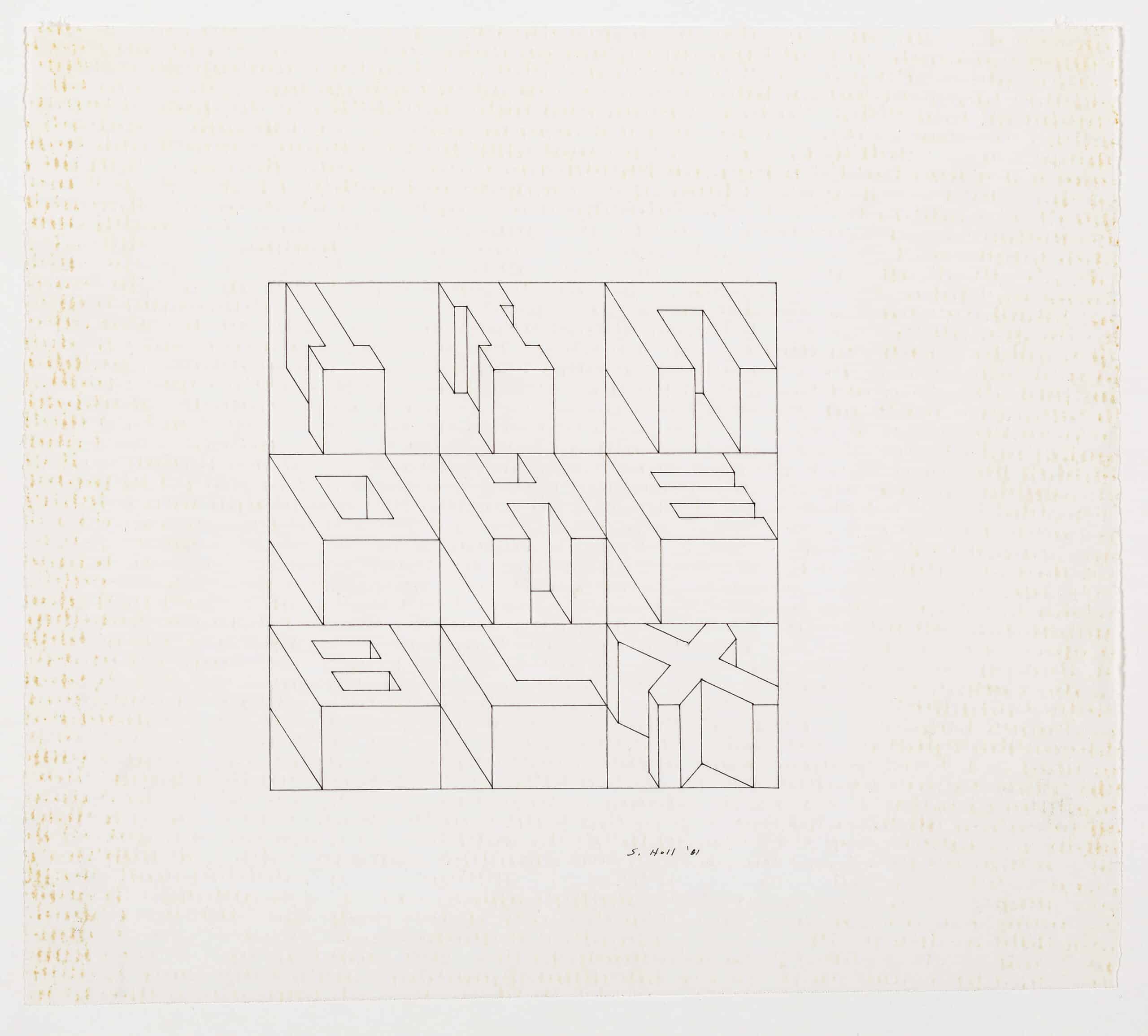

The diagram of the table can easily evoke a particular building type, like a palace, a temple, or a skyscraper. However, this resemblance is not rooted in aesthetics or visual reference. It functions similarly to the concept in The Alphabetical City, where Steven Holl presents nine building ‘types’ (a term he explicitly uses) and their combinations that were widely spread at the turn of the twentieth century in the US. Each ‘type’ is associated with a specific letter, not because they are meant to look like letters, but because they embody a certain compositional logic. They structure the interior and the exterior, define thresholds, courtyards, edges, and shape the building block and its relationship to the street, and sometimes the larger urban context. While the nine diagrams overlap with familiar letterforms—B, E, H, I, O, T, U, L, or X—this is intentional only in a conceptual sense. Unlike Johann David Steingruber’s Architektonisches Alphabet, which literally dresses letters as buildings, Holl uses the letter as an abstract reference point. The ‘type’ of a letter and the ‘type’ in architecture are homonyms: the diagram of a building or a table does not seek to become a letter, but instead the latter serves as a cognitive analogy—an abstract tool for thinking about organisation. Therefore (in architecture), referencing is not simply about replicating an object or an ensemble; it is also about quoting a diagram, along with the hierarchies and relationships it holds.

Every table, regardless of its shape, has a directionality—a facing or orientation. It may be directed toward an entrance, a view, a stage, or a focal object, or it may be centripetal. The sight, or the desire to be seen, can, in turn, determine the table’s overall orientation and position within the setting, shaping both the choice of diagram and the seating arrangement. For instance, a U-shaped table creates an inward-facing arrangement reminiscent of a cour d’honneur in front of a palace, framing a central space for attention and display. It appears in Pietro Longhi’s Banquet at Casa Nani, where the Elector-Archbishop of Cologne, Clemens-August of Wittelsbach, is seated at the centre of a formal banquet hosted by the Nani family.

The influence of the table extends beyond its physical surface; it actively structures the space around it, mediating the relationship between the table setting and its broader context. Whether placed in a dining room, conference space, banquet hall, or public plaza, the table’s position and orientation choreograph the behaviour and perspective of those seated at it, as well as how others observe, approach, and engage with it from the outside. The diagram of the table can be read in isolation, but it also responds to external conditions, creating another layer of compositional connections and becoming part of a larger spatial narrative.[6] The positioning of the table in its setting generates distinctly different meanings shaped by the spatial and typological conditions of the space. A striking example is the banquet held on January 22, 1782, at the San Benedetto Theatre in honour of the so-called ‘Conti del Nord’ (‘dukes of the North’). The setting was far from conventional. As depicted by Gabriele Bella, a large circular table was placed prominently on the stage, while spectators in the theatre boxes observed from above. This arrangement made the table simultaneously the visual and the symbolic focal point of the space. The stage functioned as a platform, and the round table—spatially and symbolically detached—presented as something meant to be seen. The traditional connotation of the round table as a symbol of unity and inclusion was quietly subverted. Those seated at the table became figures on display, while the surrounding audience assumed the role of silent observers. The separation was not overt, yet it was intentional, transforming a shared act into a carefully staged spectacle.

But the diagram can also be appropriated to question hierarchy and authority, rather than affirming it. In nineteenth-century France, where political assemblies were banned, reformers organised banquets as a legal loophole to gather en masse. These banquets—the Campagne des banquets—demonstrated how the table can become a space of political subversion. They played a pivotal role in the lead-up to the February Revolution of 1848, which resulted in the fall of King Louis-Philippe and the establishment of the Second Republic. The table entered public space not as an extension of aristocratic convention, but as a tool for assembly and collective resistance. The table was used as it was intended, but the diagram was repurposed, subverting its meaning, converting familiar forms into vehicles for critique. The appropriation of an established diagram by those once denied a seat at the table is a gesture that disrupted established orders, allowing new forms of political presence to emerge. The diagram persists across political regimes, carrying within it the potential to shift meaning, reframe power, and challenge the conventions it once upheld. The diagram does not disappear or transform; what changes is the reading of it. Hierarchies—both compositional and societal—are not abolished but reorganised according to the renewed purpose.

Like architecture, and like the table, the diagram captures conditions and communicates the social fabric it emerges from. It is not merely about form or coherence; it is about power, orientation, and relational dynamics. It is a structure generated by society and, in turn, generates it. To table is to activate a moment in which society reveals itself through form. It is the convergence of an event, participants, and a spatial configuration; ‘to table’ is to engage, debate, celebrate, to enter a shared space where roles are clarified and a group comes into being, drawing a line between including and excluding, binding and defining.

Notes

- The British usage originates from the physical act of laying legislation on the Table of the House in Parliament—once a motion is placed on the table, it becomes a subject for debate and negotiation. In contrast, the American usage has always been more procedural than physical; ‘to table’ in the U.S. means to postpone or suspend discussion, a meaning that has become entirely figurative. This duality extends beyond language into broader conceptual and material domains.

- An architectural diagram is a tool that allows the visual representation of an object’s structure—its components, their cohesion, and the overall integrity. It serves not only as a means of visualising an idea, but also as a method for analysing and reflecting on form. Across practice and theory, diagrams are mainly associated with a formalist approach to architecture in which form is treated as a self‑sufficient and autonomous system reducible to purely geometric or compositional structures. However, diagrams are not concerned with form for its own sake, but also serve to articulate principles that shape social ties. A diagram is an index that reflects and in turn actively constitutes socio-political and cultural relations: establishing hierarchies, defining roles, formulating collective interactions, and recording group dynamics.

- The ‘head’ is placed where it is for a reason: it is the only position that aligns with the axes of symmetry and stands apart compositionally. Out of two possible positions, only this one is truly unique; the other, while symmetrical, follows the same logic as the other arms and thus does not stand out in the same way.

- In some configurations, a single ‘head’ stands in opposition to all other seats; in others, two or more ‘heads’ can share prominence, creating multiple focal points. Most commonly, the ‘head’ appears at one of the short, terminal sides of the table, where two unique positions face each other, each may imply a different status, yet both outrank the surrounding figures. Beyond the ‘head’ or ‘heads’, there are other roles, such as the ‘hands’, seated immediately to the left and right, which form their own hierarchy according to proximity to the head.

- The sense of equality evoked by the circle stems from its geometry: all points on the circumference are equidistant from a single centre. This suggests equal distribution, yet the centre remains a fixed point of orientation, marked as the spatial anchor of the whole.

- That importance is evident in the drawing Plan of the Coronation Procession, 1821 (Parliamentary Archives, LGC/5/2/1), which depicts the entire ceremonial route—from Westminster Abbey to Westminster Hall—culminating at the banquet table within the Hall.

With special thanks to Ximeng Luo and Maxim Zuev.

*

Sara Gohberg is an architect, educator, and researcher. She is a co-founder of the collective vol’naya and has collaborated with Bureau Alexander Brodsky and Fala Atelier. Currently, she is a Research Associate at Gestaltungslehre und Entwerfen, TU Wien. Sara holds an MA from London Metropolitan University and an MSc from The Berlage, TU Delft.