Elizabeth Chesterton & Tomorrow Town: A New Town Thesis by Architectural Association Students

In 1999, I was an undergraduate at Edinburgh University studying Architectural History when I undertook a work placement at the university archives. Here I was asked to help organise an uncatalogued collection received from the Patrick Geddes Centre at the Outlook Tower. Within this collection were 12 portfolios.

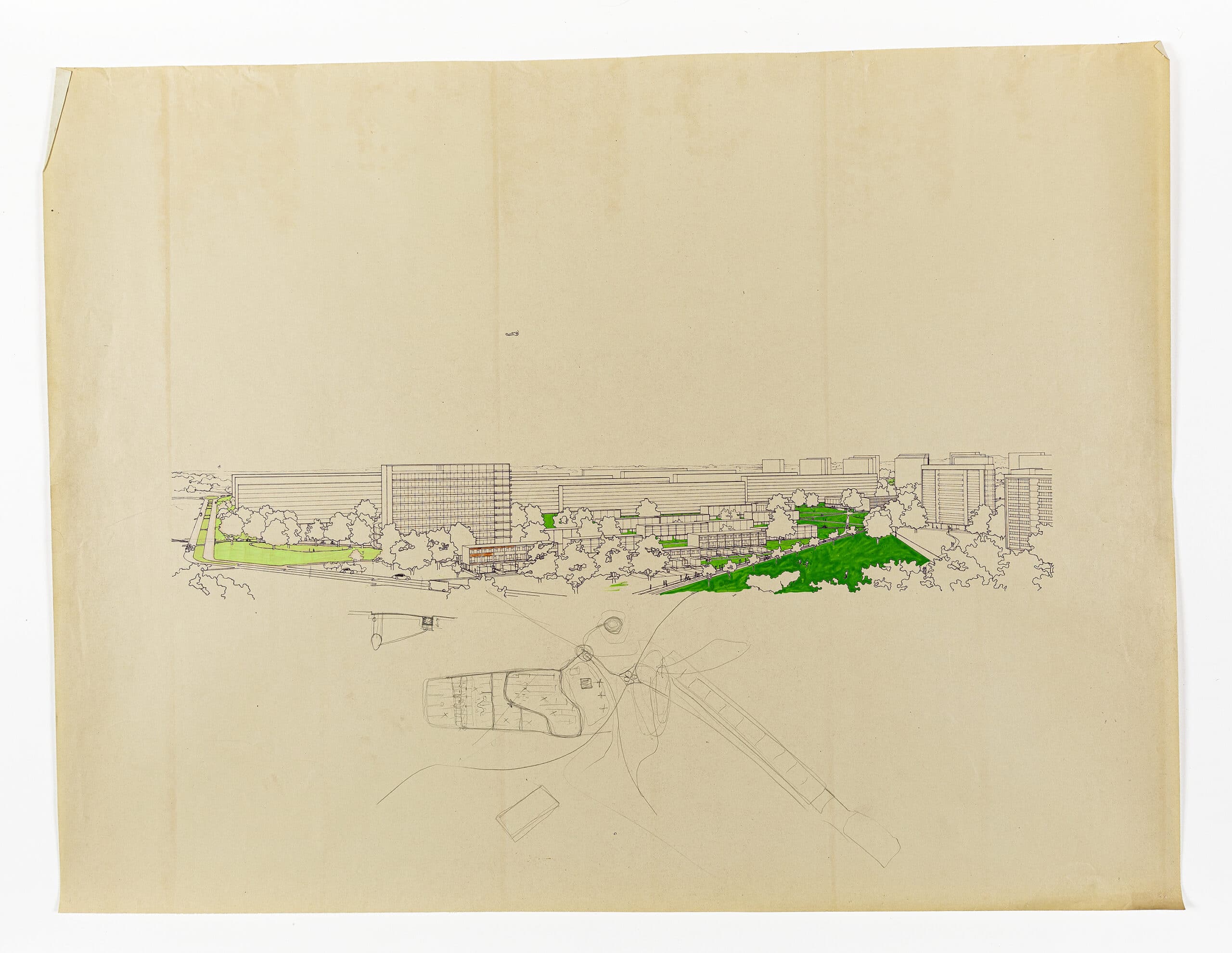

Portfolio 7 particularly caught my eye as it contained beautiful, brightly coloured drawings, looking as fresh as the day they were made. There were around 90 sheets in total, showing details for a designed town. On the rear of each sheet was stamped ‘Architectural Association, School of Architecture, Unit 15, Spring Term 1938’. This was the starting point for a research project which culminated in the publication of my paper: ‘Tomorrow Town: Patrick Geddes, Walter Gropius and Le Corbusier’.[1]

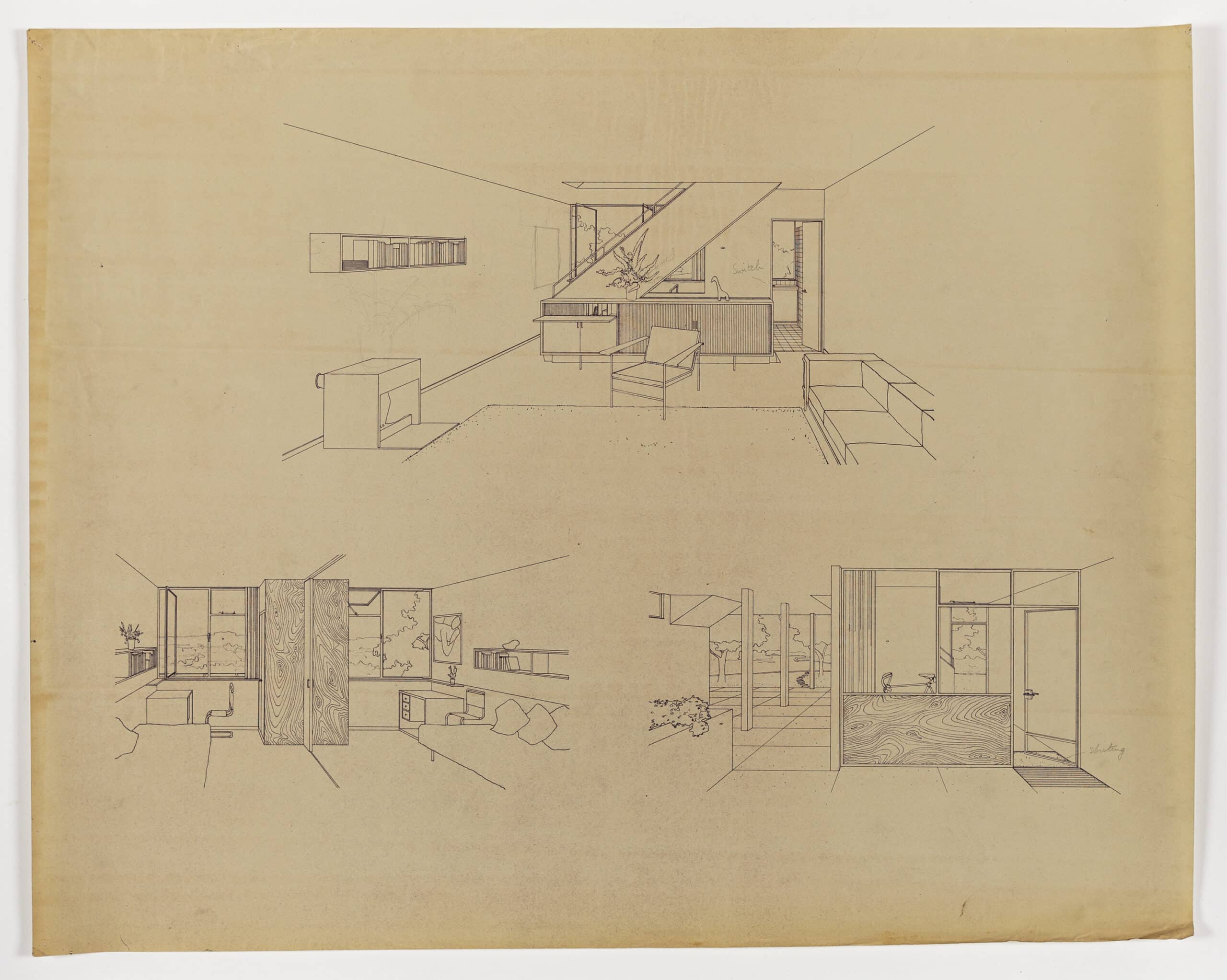

Twenty-three years later, Drawing Matter found me—through a clearly functioning grapevine—working as a Development Management Planner. Drawing Matter had a collection of drawings belonging to the late architect and urban planner Dame Elizabeth Chesterton, and within this collection were 23 drawing sheets showing details for a town. These drawings appear to be part of the same new town project that Architectural Association (AA) students had undertaken in the spring of 1938. Elizabeth Chesterton was one of these 13 students and their unit master was Eric A. A. Rowse.

… Could I provide some comments, reflections or additional information, asked Drawing Matter. Why not, I replied.

Tomorrow Town

The 1930s were an exciting time to be an architectural student. Modernist urban theories from the continent had begun to gain real traction in the UK. The industrial age had produced ‘modern life’, and Modernists believed the old-fashioned towns and buildings no longer met the needs of ‘modern man’. Rowse and his final year students sought to advance the Modernist cause through their showpiece, ‘Tomorrow Town’.

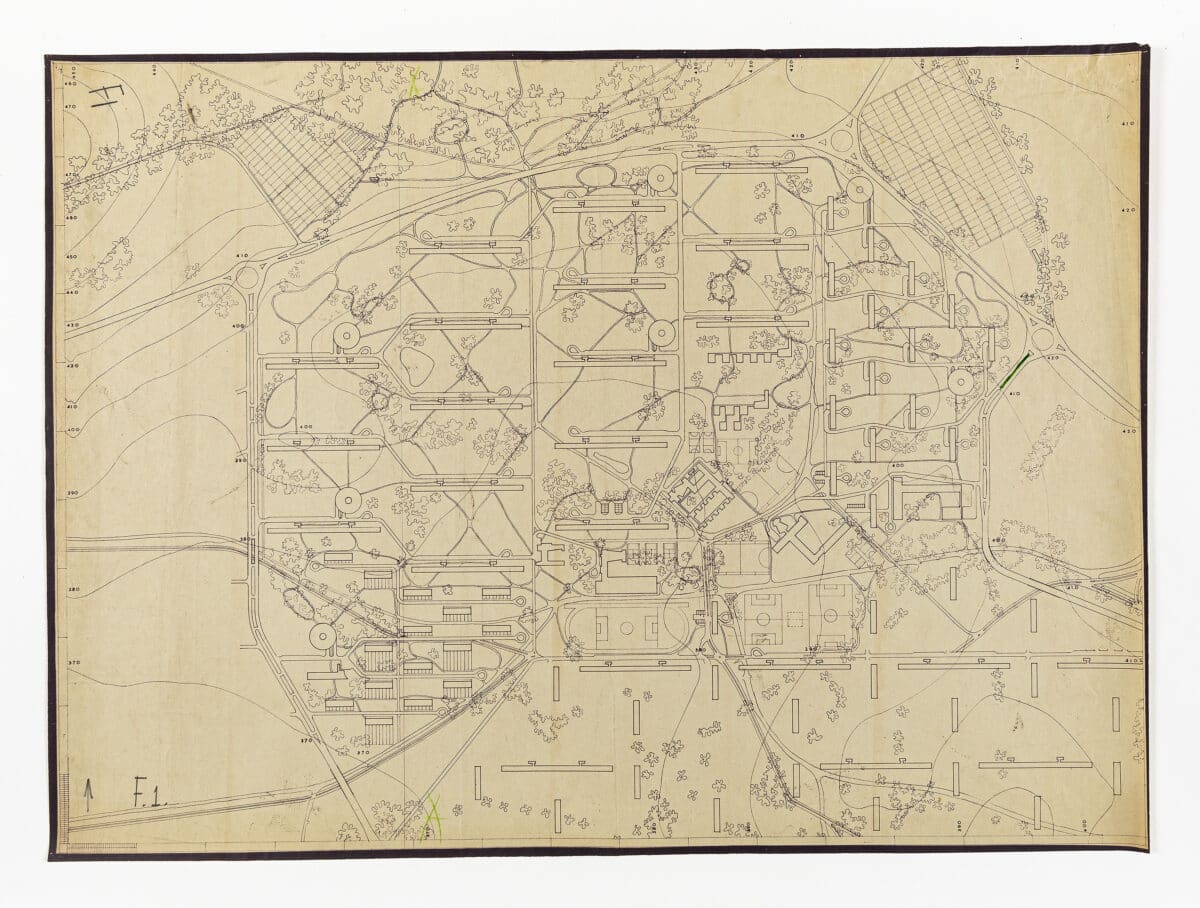

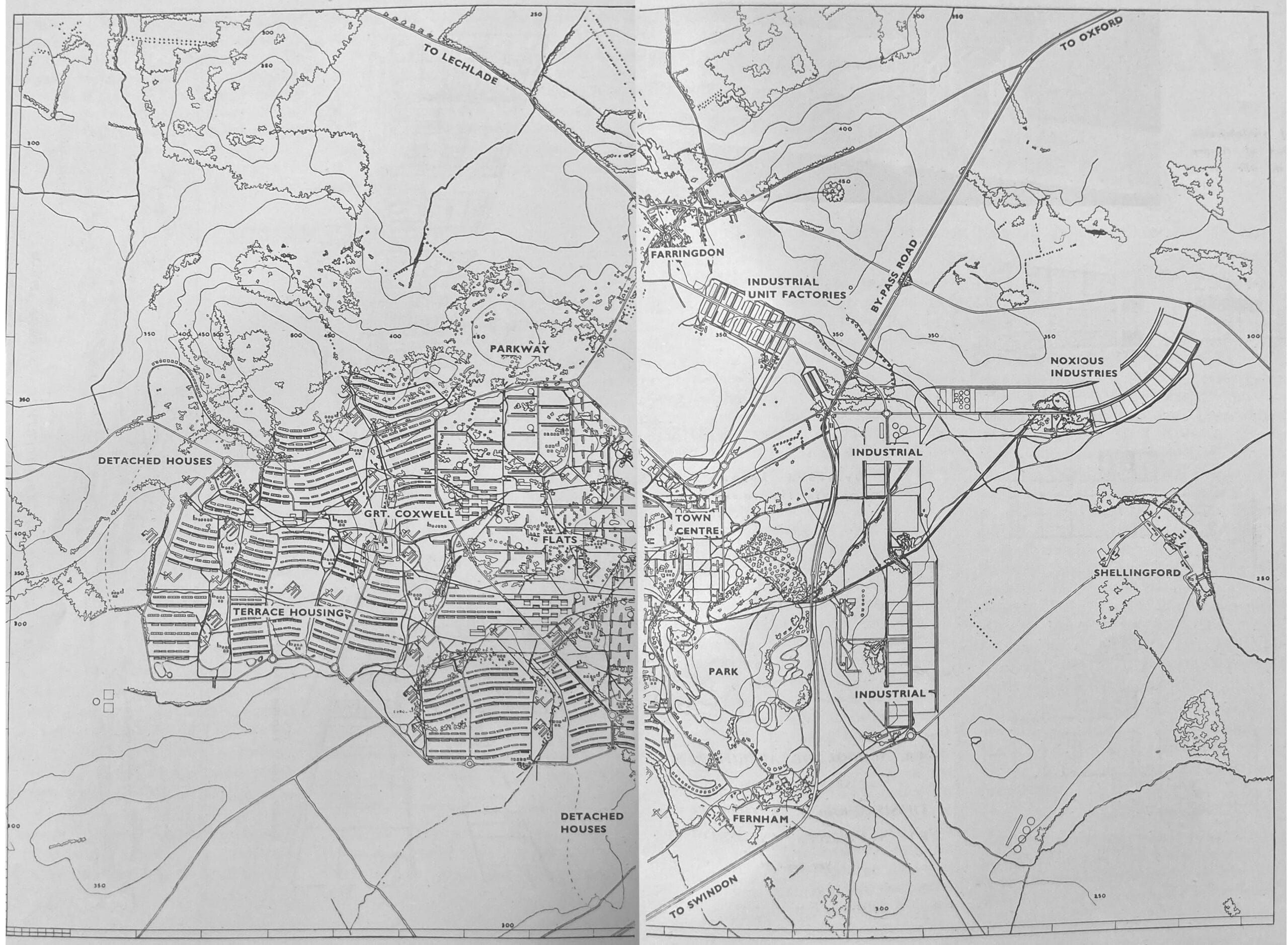

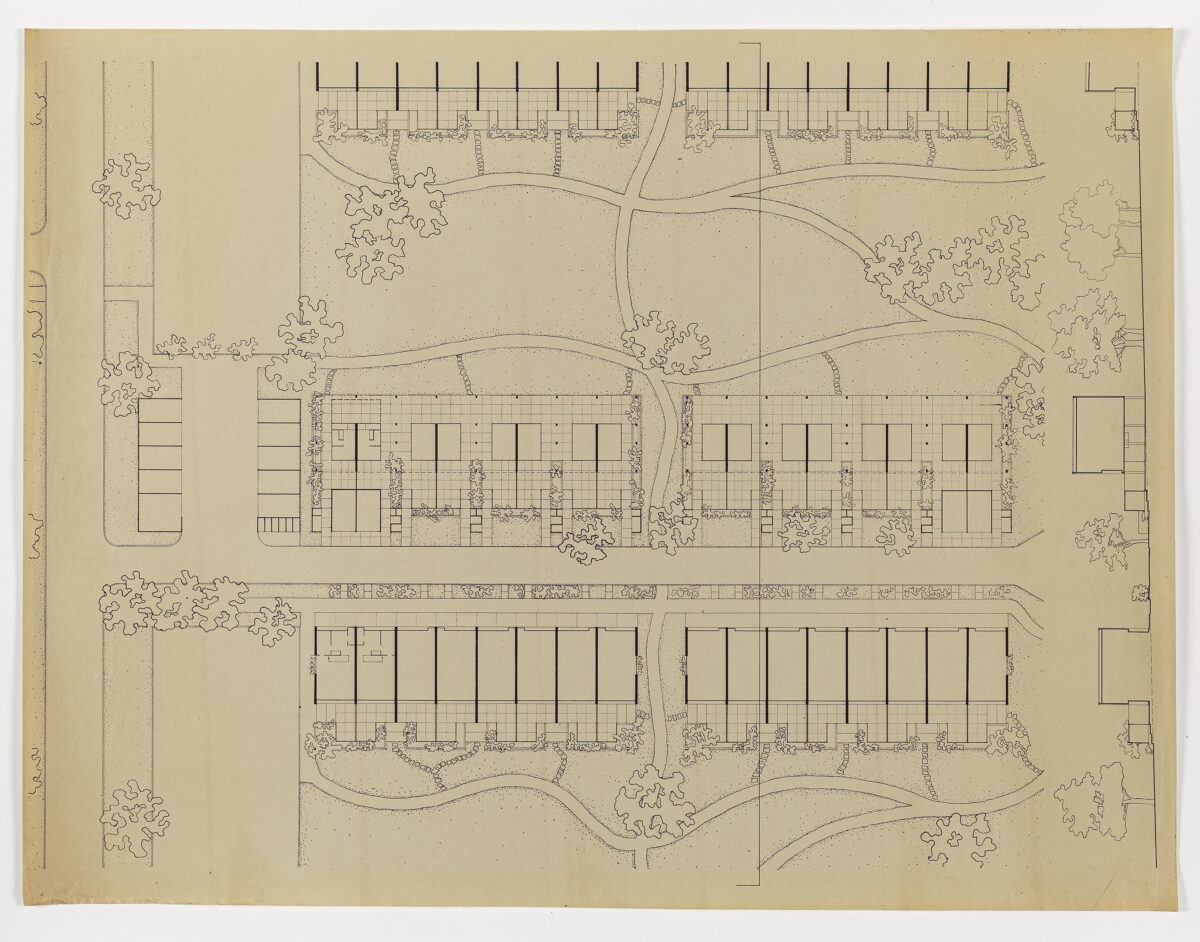

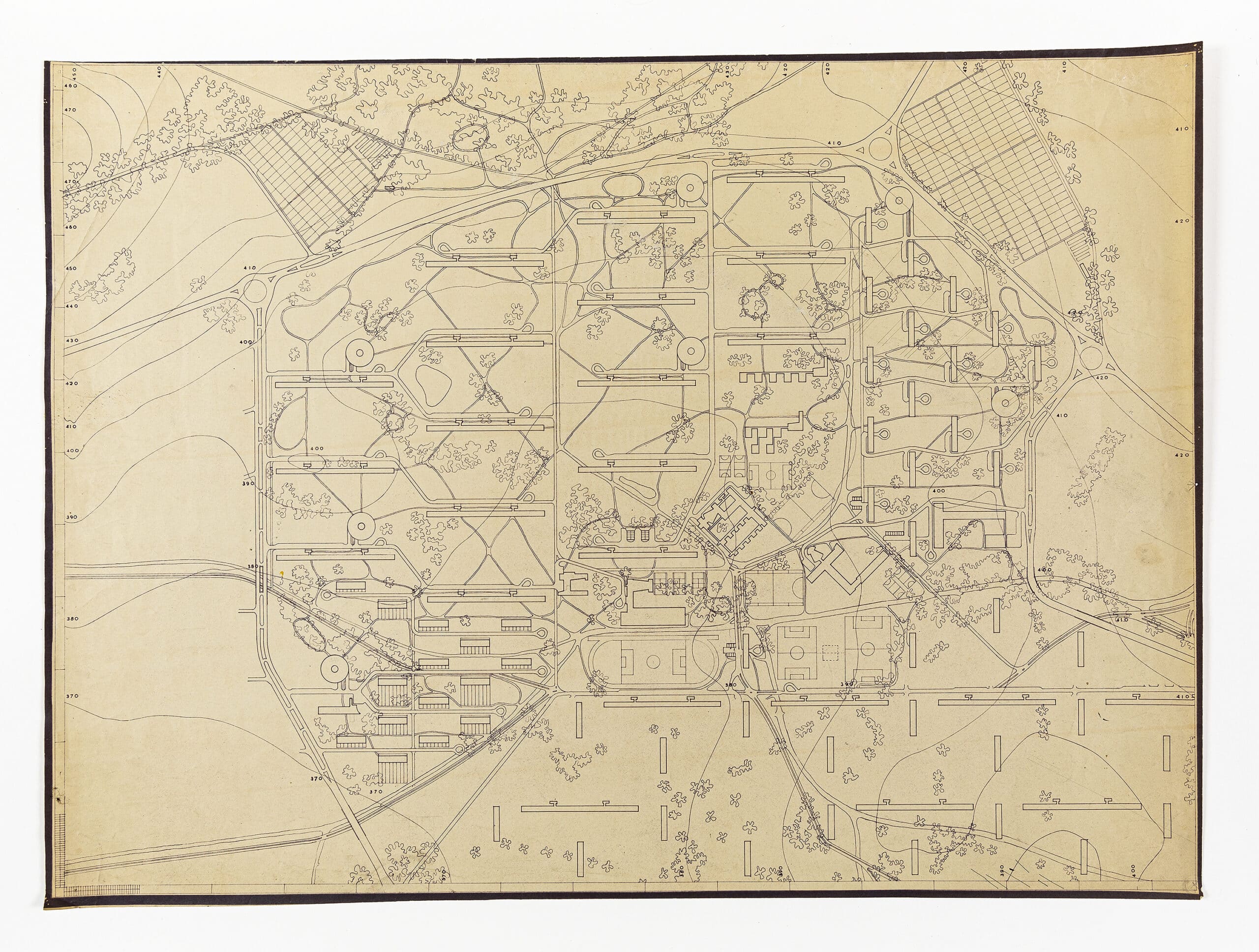

Tomorrow Town was to be a comprehensive, self-sustaining ‘new town’, designed to be inhabited by 50,000 people. It was to have housing areas with community facilities and schools; a town centre with cultural buildings; an industrial park; and inter-regional transport links.

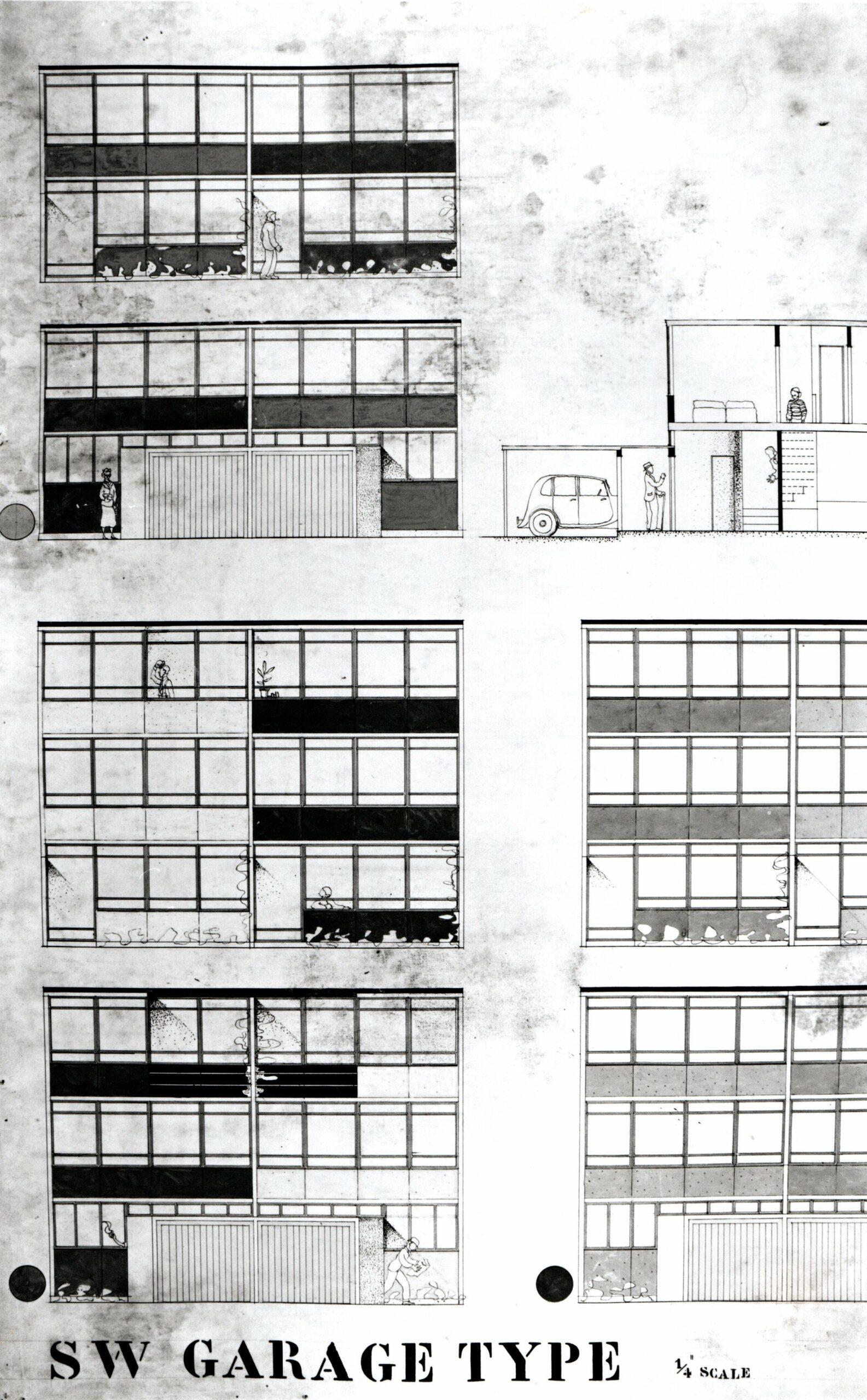

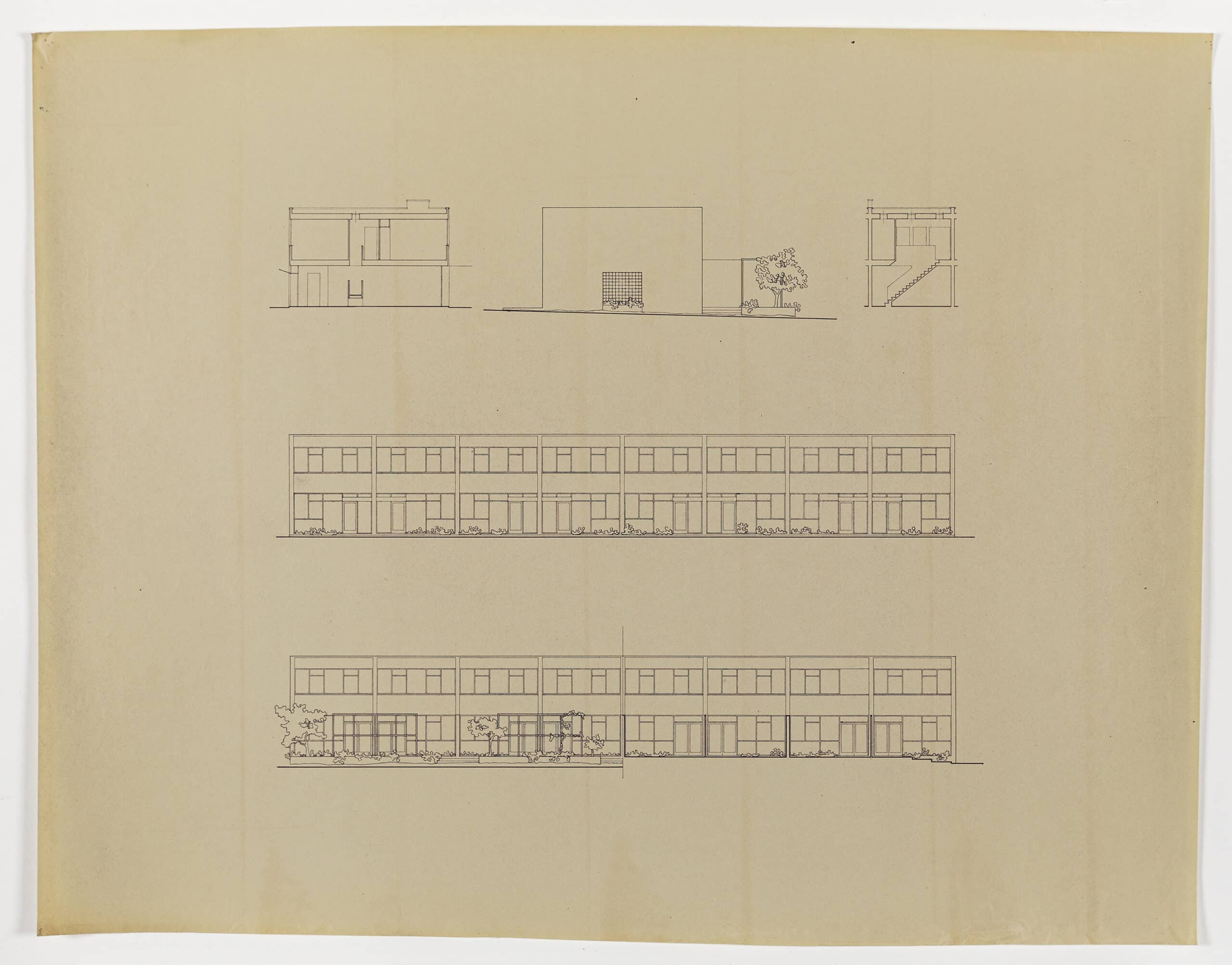

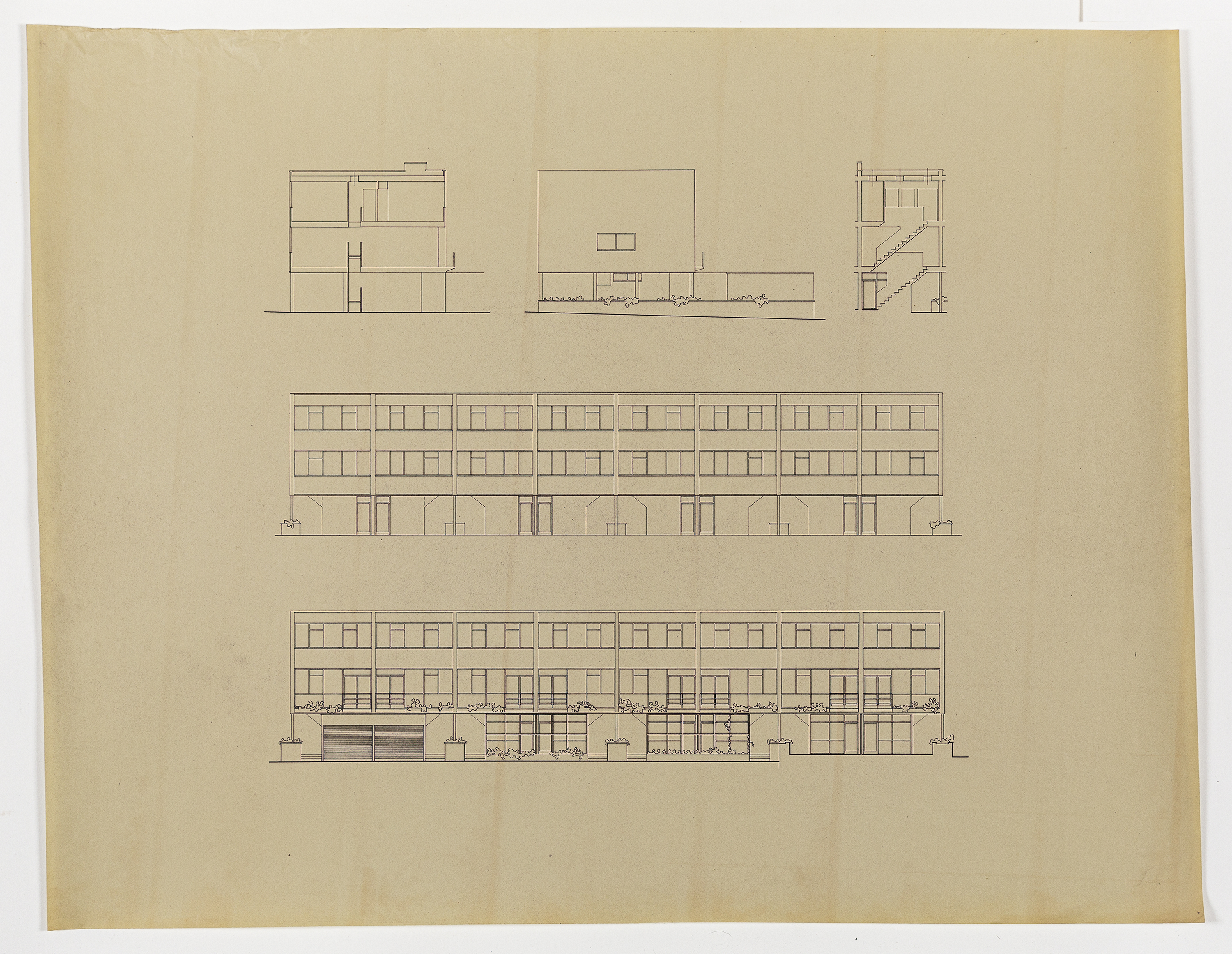

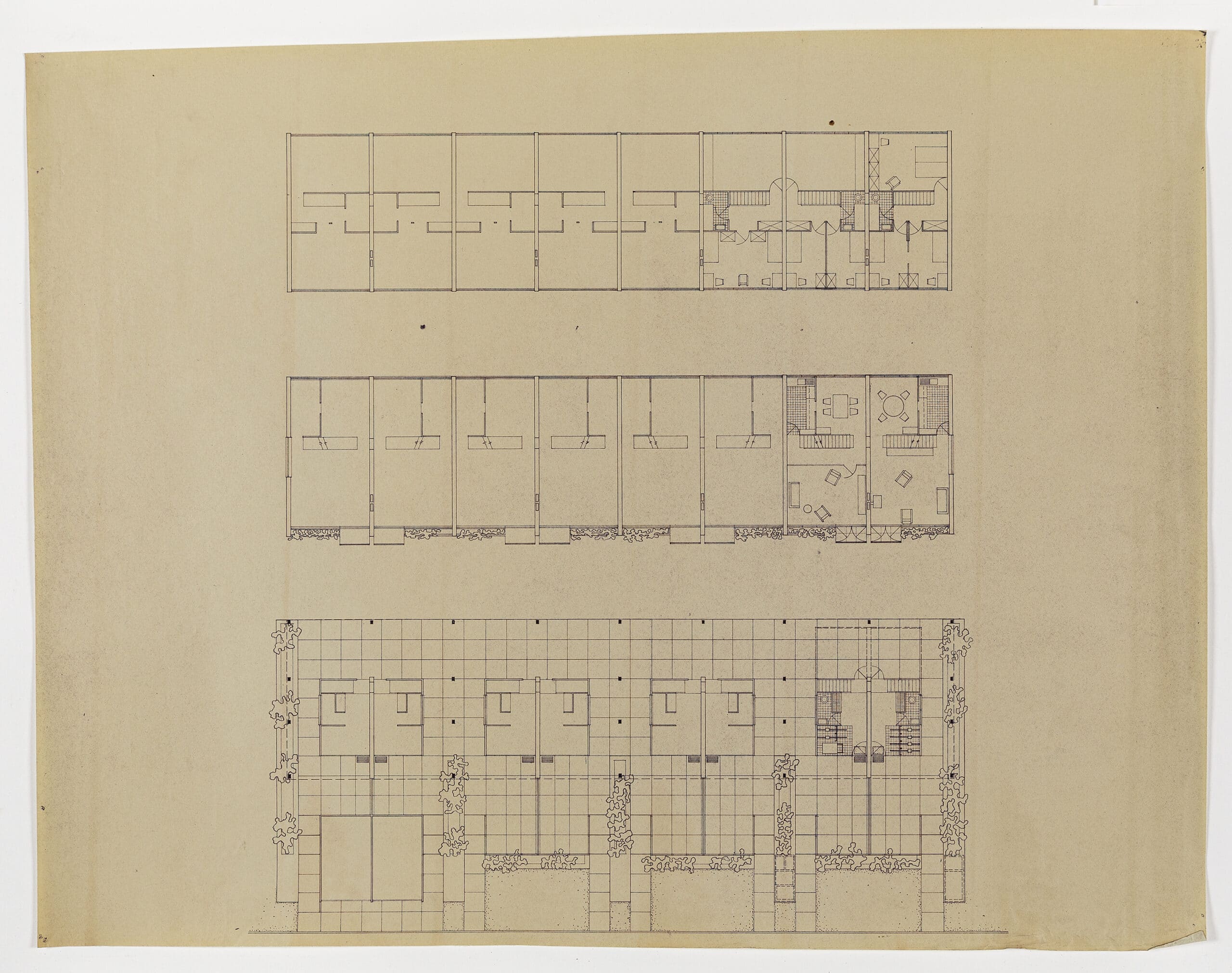

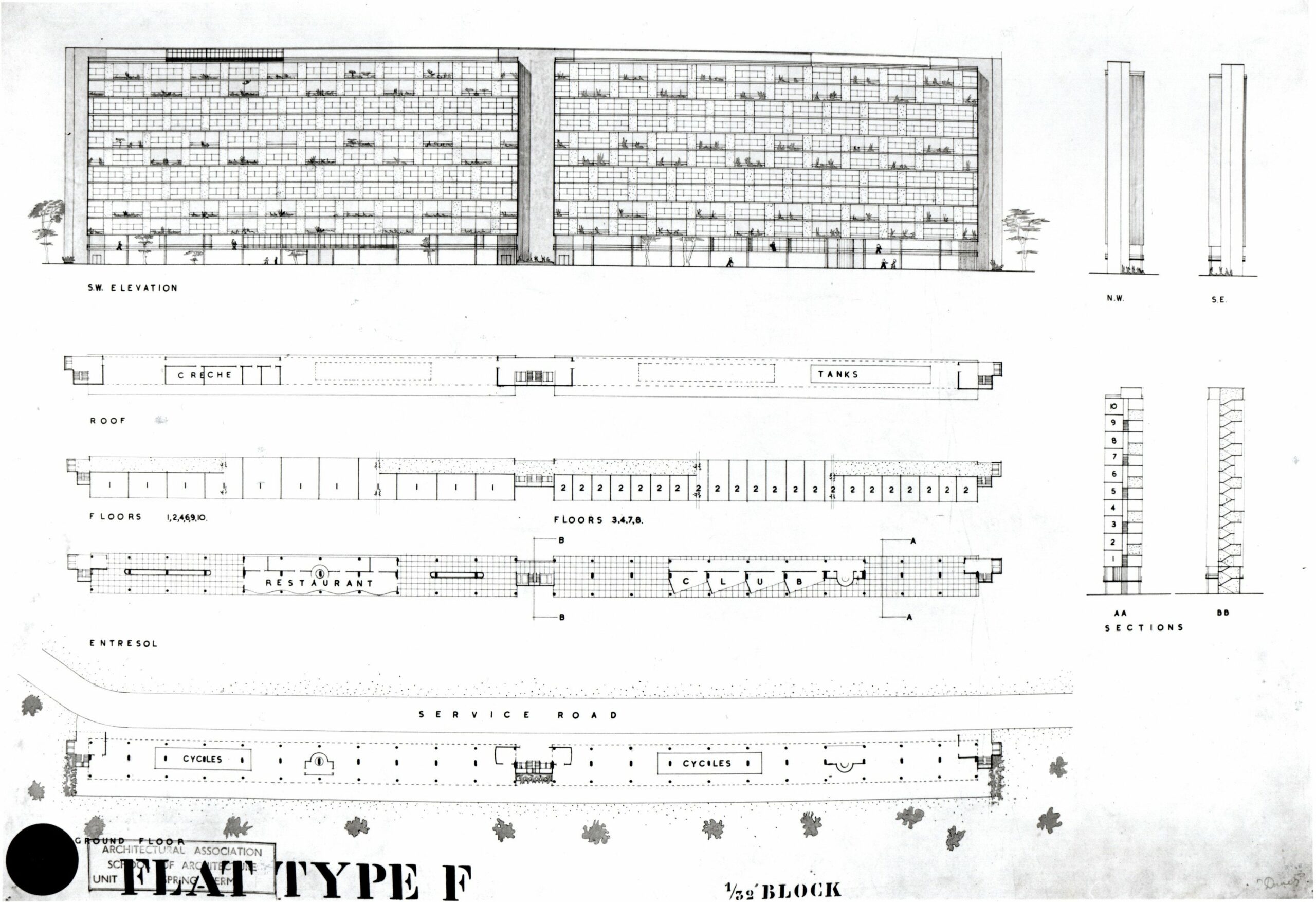

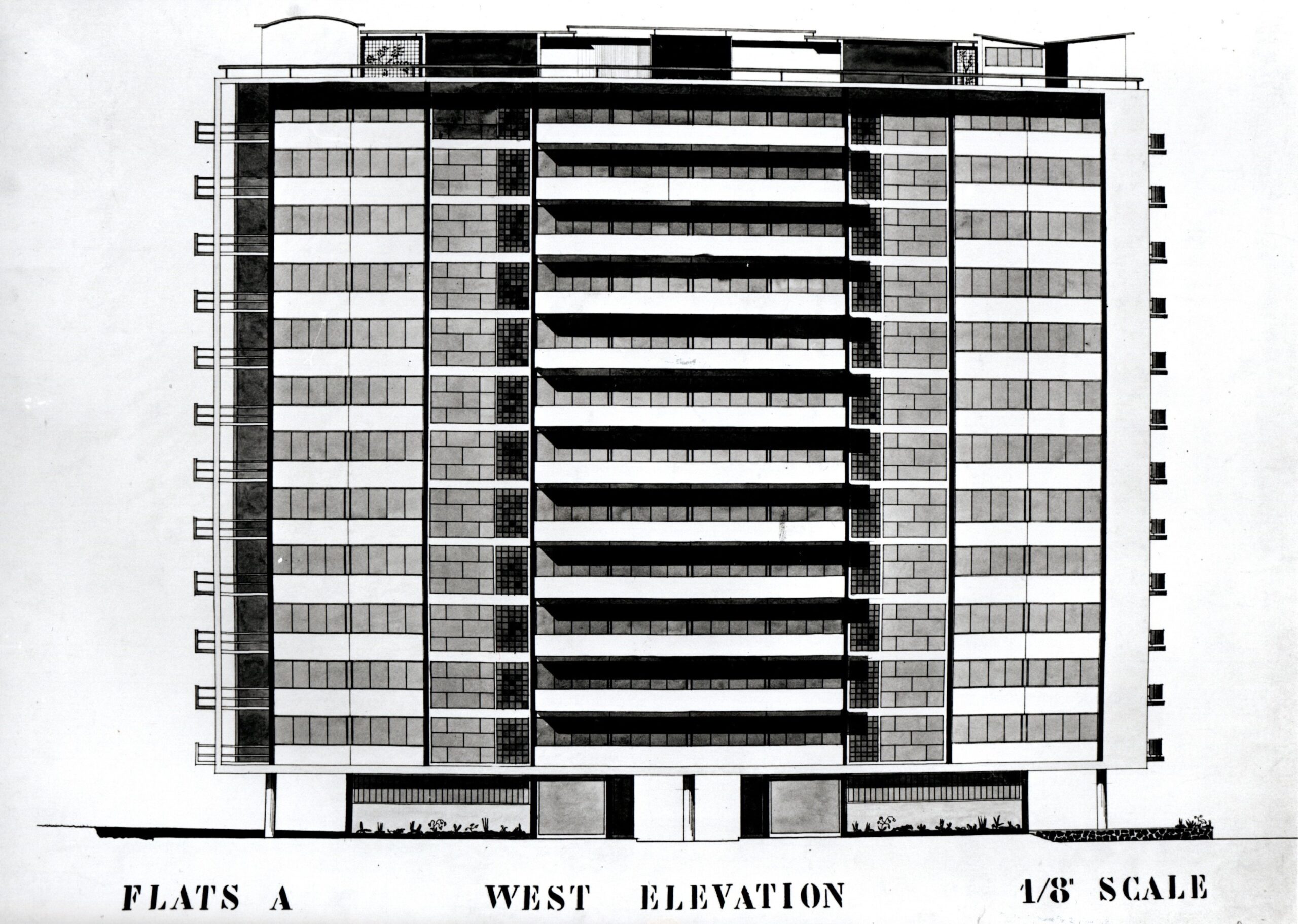

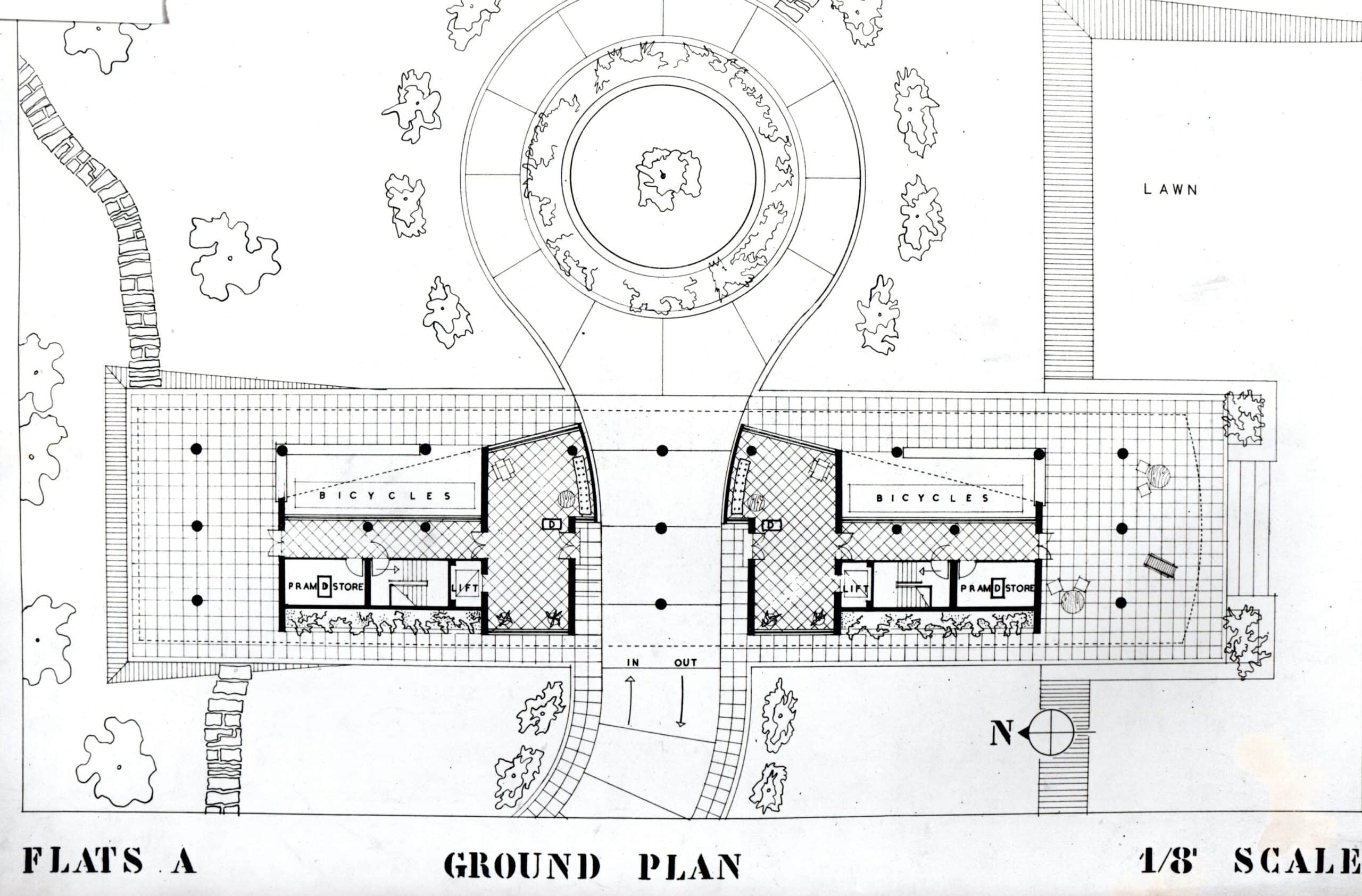

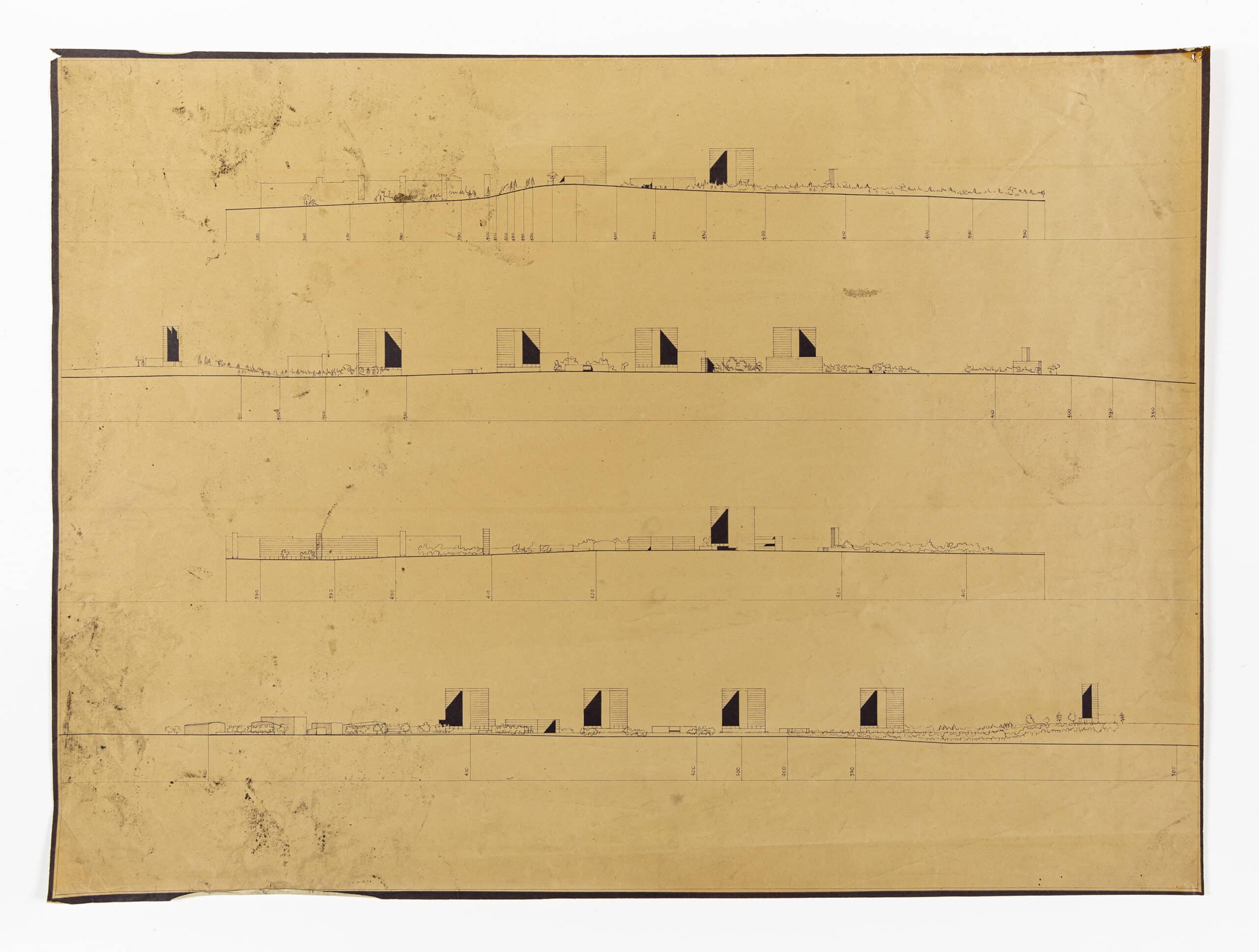

The buildings and streetscapes of Tomorrow Town are instantly recognisable as Modernist in style. The streetscapes show acres of open green space and trees. The buildings are light and simple—they sit on pilotis, they have white concrete facades, flat roofs, and ribbon windows. The roads are wide and quite devoid of traffic.

Model towns were nothing new and many had been designed and publicised over preceding years. What is interesting about Tomorrow Town is that it was designed with a level of detail intent on actually being built. For starters, and unusually for a model town, it was based on a specific site—an area of rolling countryside to the west of Oxford. Tomorrow Town’s detailing shows an all-encompassing commitment to Modernist ideals—from considering ‘modern living’ to using new structural techniques and prefabricated production, and to the way the students worked as a group, the project was set out and recorded as a process to be repeated.

Almost 90 years has elapsed since these drawings were made. What relevance, if any, does Tomorrow Town and its nascent ideas on Town Planning hold today?

Town Planning

When Tomorrow Town was designed, town planning as a profession did not exist. The School of Planning and Research for National Development, set up by Rowse in 1935, could be recognised as one of the earliest town planning schools in the UK. In a way, the Tomorrow Town thesis was an experiment to better inform the way his planning school could run. The aim of the school was to produce ‘master planners’, trained to work on a national scale using set methods. The two essential elements of this training were ‘collaboration’ and ‘research’.

The legal framework for town planning in the UK was created after WWII with the Town and Country Planning Act, 1947. Collaboration and research were then, and still are, essential procedural aspects in the now established profession of Town and Country Planning.

The first step in any Development Management process is to assess the existing site. Modern data sets and Geographic Information System (GIS) mapping have revolutionised this. Sitting at your desk, with the click of a few buttons, you can find out the level of flood risk; the archaeological sites; the built heritage protections; the natural heritage protections; the former site uses; potential site pollution; the soil quality; the current land use; planning history… the list is long. In 1938, there was no such equivalent and the AA students spent much time collecting data and undertaking surveys themselves.

The second step in any Development Management procedure is to consult and notify all stakeholders. This is with a view to gaining professional advice on things like road safety; protected species mitigation; flood mitigation; business viability reports; design advice on listed building details or on landscape views; availability of public water supply, etc. Community and local opinion is also sought and considered. Rowse saw master planning as part of an interdependent system of thought, a level of collaboration he called the ‘composite mind’. Site meetings, office meetings, online meetings all happen to enable this collaboration of thought but in times of minimal staffing and working from home, the efficient running of this aspect can be a struggle. Talk of planners and other development professionals working in ‘silos’ is a common complaint. Instead of discussions and relationships, I am often directed instead to ‘standard guidance notes’.

Housing Crises and the New Town

There is something enticing about new towns, being able to start from scratch and get every detail for a new life just the way it is required. A current-day new town could have a climate resilient location; sufficient water supply; easy access to the national grid; road layouts could prioritise active travel from the outset; buildings could have a high standard of accessibility, be super-insulated and built from sustainable materials. Retrofitting existing settlements never seems as efficient or satisfactory and the upheaval always upsets existing residents. Well, new towns are back in vogue. The Labour Government has recently committed to building 1.5 million homes in 5 years and one of the principal methods to meet this target will be ‘new towns’. A New Towns Task Force to advise the government of suitable sites was set up in September 2024.

Tomorrow Town, too, was designed in response to a housing crisis in the 1930s. Following WWI, the UK population continued its drift towards cities for work. There was not enough housing in the cities, and improved transportation meant that housing development grew instead on the outskirts of cities. London was said to have doubled in size between 1919 and 1939. There was a real fear that British countryside and agricultural land would be engulfed by suburbs.

Tomorrow Town would help solve this with an efficient use of land. It proposed generally high-density buildings with small built footprints, and was arranged to spare the best agricultural land and to retain as much open green space as possible.

The Green Belt and the Grey Belt

Tomorrow Town was to be surrounded by a ring-road, designed to keep development inside its boundaries and to protect the countryside. ‘Green belt’ policy was taken up post-WWII and has run continuously for 90 years.

The policy has its critics though. The green belt has been accused of not allowing a town to expand and evolve, reducing the amount of land available for building and pushing up house prices. Additionally, over the years some development has leaked into green belts, making them no longer so green. The new Labour Government is arguing to redesignate these areas as ‘grey belt’ and make them available for housing—the grey belt being a term for poor-quality, underutilised land within the green belt.

Hierarchy of Travel Routes

In Tomorrow Town there are roads running around the periphery of the town. At certain points the roads enter the town to allow access to the shopping buildings, where the road dead-ends. None of the town’s roads are through-roads. There are, however, separate pedestrian and cycling routes weaving across the whole town. These run through parkland and are more direct than the route the roads take. Walking and cycling journeys were prioritised over cars/buses because it was recognised that such journeys kept you active and allowed for more social interaction.

Active travel routes like these are up-to-date with contemporary transport planning principles. Active travel routes are encouraged by providing a pleasant and safe journey, and by being shorter or faster than by road.

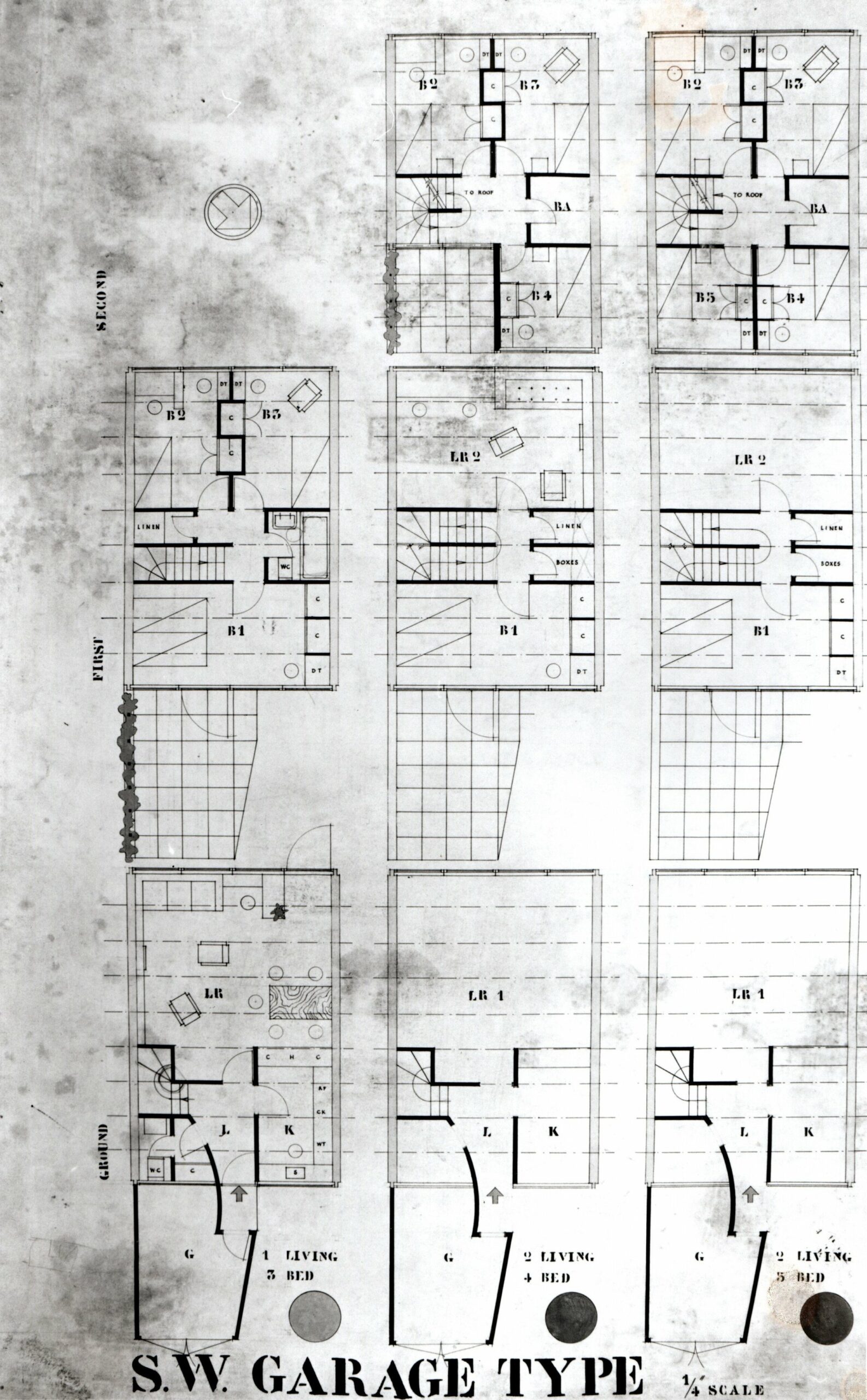

One thing which immediately caught my eye in the Tomorrow Town plans, was the lack of car-parking spaces. There are buildings annotated as garages, but their size and capacity is not stated. I wonder if the Tomorrow Town students would have predicted the popularity and affordability of cars in the future, and their domination. Current off-road parking requirements depend on the size of the dwelling, but for a family home it is usually 2-3 parking spaces. This would have changed the look of Tomorrow Town considerably.

Many urban planners see the private motorcar as the worst thing to have happened to towns and cities. The more space that is provided for cars the greater becomes the need for the use of cars, and hence to provide even more space for them. The supply and demand for car related facilities becomes a self-propelling spiral. If the Tomorrow Town team provided good public transport as an alternative, perhaps the need or want for cars in their new town would not grow to the levels it has in 2024.

Neighbourhood Units and the Community

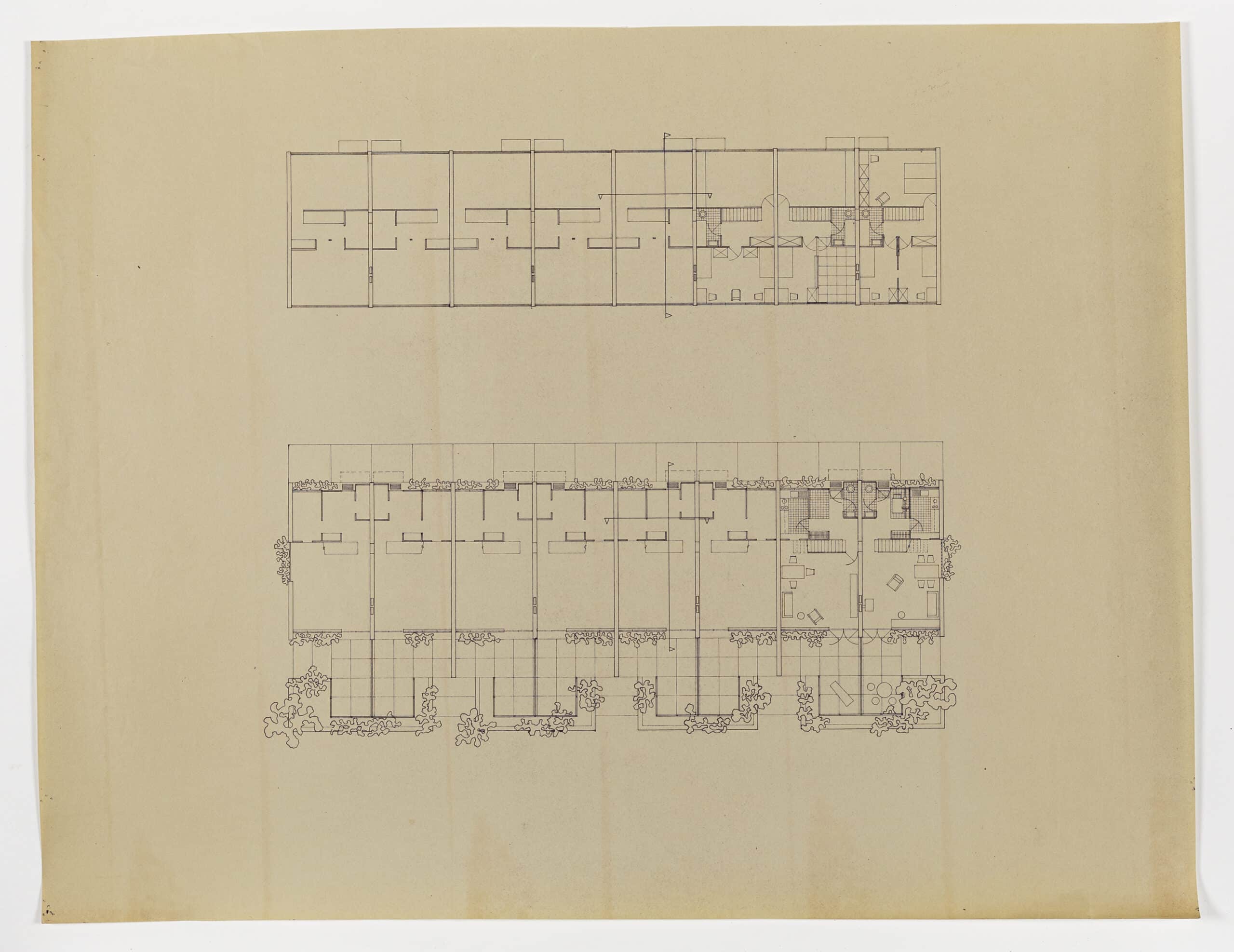

In a deliberate attempt to avoid the lack of community which prevailed in the burgeoning suburbs, Rowse and his students wanted to support the formation of communities. Tomorrow Town’s population was to be arranged into smaller groups, a system of villages coordinated into an urban region. Housing was grouped together to form intimate numbers, separated by trees and distance from other housing groups. An apartment block for example was a ‘village’ of 300 people, a courtyard of 3 apartment blocks was a community of 900.

The students prescribed a friendship group of around 20 people; an acquaintance group of 250 people; and a community group of 2000 people. There were communal living-rooms; sub-community centres; creches; community centres; allotments; communal workshops and garages. Each community area had a nursery; a primary school; a shopping building; a club; and a clinic; sports fields; and a secondary school.

This level of public facility provision requires a lot of money to manage and up-keep. I found no mention how the finances for Tomorrow Town would work. There seemed to be a presumption by the Tomorrow Town designers that public funding would provide for on-going maintenance of such facilities, and that this funding would be available in perpetuity. History has shown us that when social housing estates were built in Britain between the 1950s and 1980s, money was always tight and the easiest place to cut costs was from the communal facilities. Here the new inhabitants could find it hard to form close knit communities and they often felt isolated. There were other issues at play, but a principal factor in the ‘new town blues’ was the lack of well serviced communal areas, local shops and good public transport.

Density in Urban Planning

The Tomorrow Town team did realise there was a minimum population and building density required to make community facilities work and to make a town and its amenities sustainable. Tomorrow Town had calculated that minimum number was 50,000.

It is still a hot topic in urban planning circles: what minimum density will allow the viability of public facilities, or even just a café? The Covid-19 lockdowns put a spotlight on the importance of the liveability of neighbourhoods, with people spending more time locally. Planning professionals encouraged the notion of a ‘15-minute neighbourhood’ aiming to make it easier for people to meet their daily needs within a 15-minute walk, bike ride, or wheel trip from home. This notion was far from new, even for the Tomorrow Town designers.

Looking at the plans for Tomorrow Town, the amount of open space between buildings seems frivolous, even alarming. Again, the question of maintenance crops up. Who was going to cut all that grass, and who was going to pay for it? ‘Green corridors’ are encouraged in modern urban planning and they must have sounded like a good idea in 1938 as well. The old-fashioned towns that Tomorrow Town was aiming to replace could be over-crowded and have limited access to green space, sunlight and fresh air. In reality, however, Tomorrow Town made it hard to visit friends or relatives in an adjacent housing group. It would have been a lonely and long trek, somewhere between 300m and 4km in length, over open ground. The experience would not be pleasant if it was raining or dark, or if you had young children with you.

High Density Living

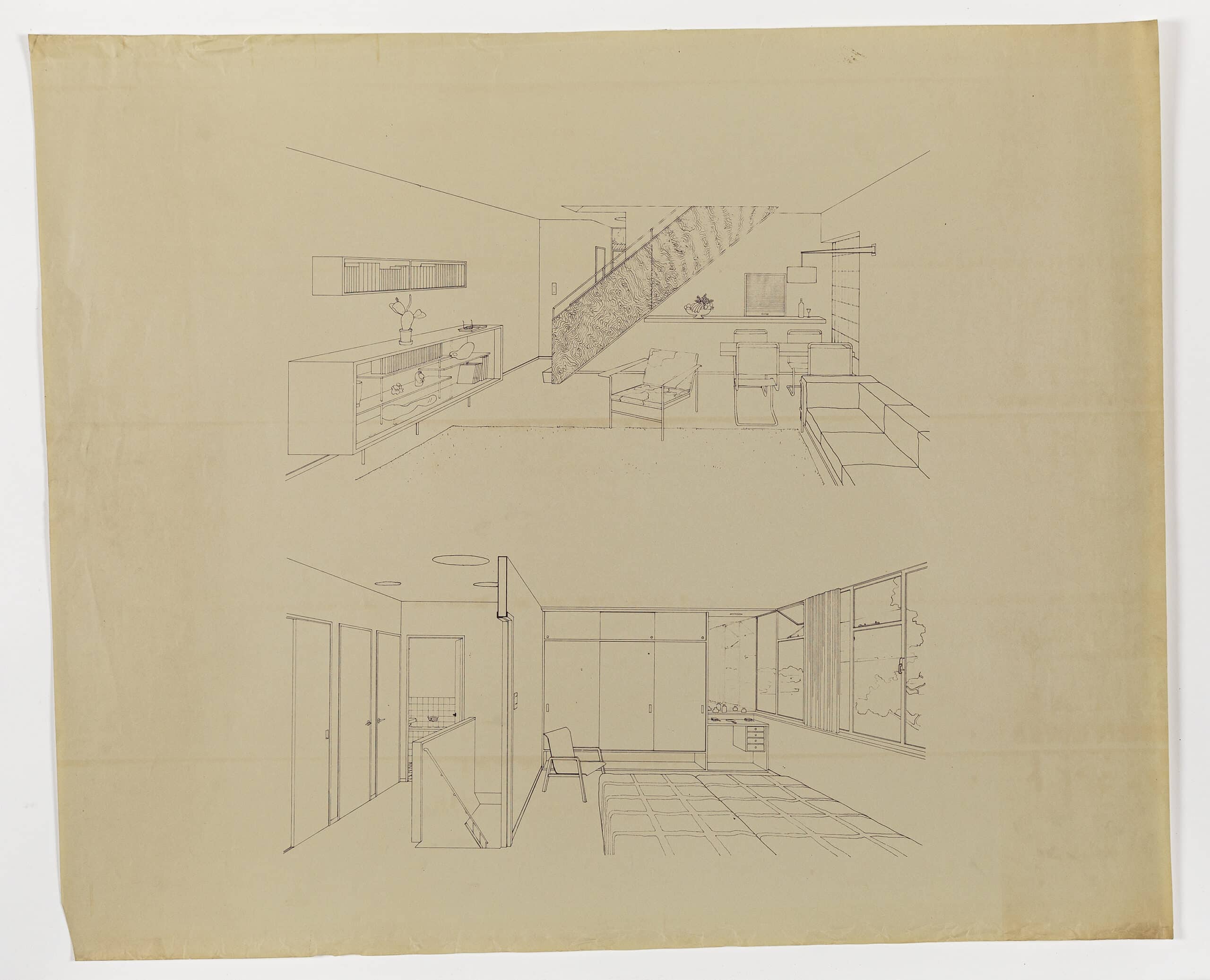

The spaces between the Tomorrow Town buildings were vast but many of the residential buildings were designed to be high density themselves. One of the proposed apartment blocks took on the idea of a ‘unite d’habitation’—dwelling cells. A 400-room tower block was designed where each ‘cell’ was provided with a bedroom, cupboards, and a combined kitchen/bathroom. The tower blocks in Tomorrow Town were located closest to the town centre, within easy reach of the main cultural and entertainment venues.

Tower block living got a bad name in Britain for a number of reasons. They began as a cheap housing solution in the 1950s. As a cheap build, they often developed structural problems and damp ingress; they were susceptible to fire risk; and they were unsuited to families with young children. They were often located out of town, away from amenities and work, and consequently became slums.

Wholesale demolition of tower blocks began in the 1980s but they have not been dismissed as a housing option. With the current price of renting in a city centre, the Tomorrow Town vision is not so far off the mark. Such habitation spaces exist and are sought after as a place to sleep and store some belongings, while the occupants’ socialising and leisure and work takes place in the city itself. Indeed, for the more affluent, luxury tower block apartments are popular with young or single professionals.

Modern Lifestyle

The question of how modern man would live in the future was regularly debated in Modernist circles. The Tomorrow Town team considered that modern man would have fewer belongings and be more mobile, moving house many times as his/her circumstance changed. As a young, single worker they would live in a small apartment; as a young couple they would get a larger apartment; as a family they would move to a house; and as an older person they would move to a bungalow.

In this I think the Tomorrow Town team failed to consider the human characteristic to grow-attached or at-home with a physical area or a house; or the human desire to live close to family or old friends. They also failed to be flexible or provide for variety in their living models. Current house design makes more effort to be adaptable to future, unknown needs. Today’s architects talk of multi-generational living—where children in their 20s (saving up for a mortgage?) still live with their parents; where grandma/grandpa (aged and no longer coping alone?) have a small annexe next to the house. There are housing complexes which mix student accommodation with accommodation for the elderly and this unpredicted combination has been proven to work well for both types of occupant.

Protected Features

An unusual feature for a Modernist-inspired new town was the preservation and protection of existing site features. The students for example decided to retain and incorporate the main street and historic buildings of the existing village, Greater Coxwell. Their proposed terraced housing was to slip in either side of the original street. Existing trees were to be retained when at all possible. The trees were kept to enhance the appeal and variety of the acres of parkland and to also buffer the separate neighbourhoods and zones of the town.

Following geology surveys, the Tomorrow Town team decided not to build on the best soil. The deeper richer soil was to be preserved for growing fruit and vegetables. The location and curve of the town’s streets were arranged to preserve the best agricultural soils.

Legal protection for historic buildings and for certain trees began in the Town and Country Planning Act 1947, and has remained an important consideration in planning decisions. Today the protection of agricultural soils is essential for food security, and although it remains a planning consideration it is often trivialised as an out-of-date policy. The protection of soils and land for the sake of flora and fauna however has become an extremely popular and current notion. Biodiversity Net Gain became a legal requirement in 2024.

* * *

Tomorrow Town hit the nail on the head in a surprising number of aspects concurrent with modern day town planning policies: traffic segregation; de-prioritisation of cars; 15-minute neighbourhoods; active travel routes; access to green space; urban density versus viability; protection of historical buildings; protection of trees and biodiversity and landscape and agricultural soils.

The lasting legacy of Tomorrow Town, though, must be the impact its working methods had on the planning schools and the future profession of town planning: ‘collaboration’ between built environment professionals, the public, and the planner; and ‘research’ to enable the best use of the site and is resources and assets.

What I enjoy most about Tomorrow Town is its certainty and ambition; its energy and optimism. These attributes seem missing in much of today’s profession where town planners are on the one hand blamed in the media and by politicians for the housing crisis, for flooding, for the death of the high street, for biodiversity collapse (you name it!) and on the other hand town planners are restricted from acting to their full capacity by lack of resources. In 1938, town planners were on the cusp of being invented and the AA students believed they were the architects of the future.

Where Tomorrow Town worked less well, is in its lack of built flexibility. How was the town to expand and evolve? Where was the adaptability for life’s variety or for a future no one can predict? Additionally, some of their ideas on how to live a complete and healthy life in Tomorrow Town seem overly controlling. Rowse, for example, had collected recipes for recommended foods; a level of communal living was encouraged; ideas on preventative medicine were pushed… these such things have little place in current Town and Planning legislation. I found no mention either of how Tomorrow Town would be financed; where the land would come from; who would build it; and who would go on to maintain it. I find this omission a gaping hole and perhaps a little naïve.

Additionally, I do not see myself living there. There is too much empty space between the buildings. At a ratio of 85% open land to 15% built footprint, can it even be called a town? I am still concerned about trying to visit friends in the adjacent housing group, and that long trek over open scrubland in the dark and rain with two toddlers in tow.

Notes

- Mary Ashton, ‘Tomorrow Town: Patrick Geddes, Walter Gropius and Le Corbusier’, in The City After Patrick Geddes, ed. by V. Welter & J. Lawson, (Edinburgh: V. P. Lang, 2000), 191–210.

Mary Mitchell (née Ashton) is a chartered member of the Royal Town Planning Institute and has worked as a Town and Country Planner for over 17 years at Local Government level.