Yasmeen Lari: Drawn Closer

In 2005, earthquakes in northern Pakistan killed 80,000 people. This was an eye-opener for me, and I was drawn to work with these remote, impoverished mountain communities, to help to rebuild their lives. Having retired from conventional architectural practice, and this was something I’d never done before. Unlike NGOs offering to build prefab housing or using cement concrete blocks and steel girders, I wanted to build reusing materials to hand. I prepared some sketches before arriving in the mountains, but unlike life in an architectural office, it was impossible to issue drawings for someone to follow in these remote, devastated places. This was self-building. People had to do things themselves. If mistakes were made, we had to incorporate them. This was an entirely different way of working.

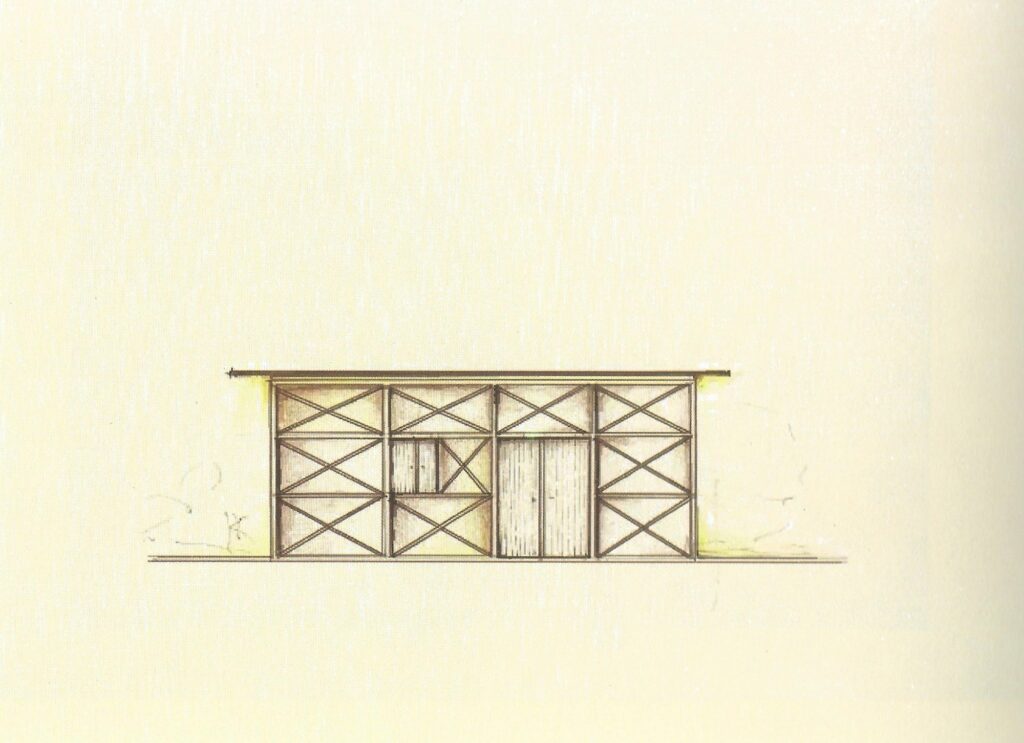

The principle of construction in an earthquake zone is that all building elements must be interconnected: the walls, the roof, the foundation. In stone walls you have to build in wooden ladder-like frames/assemblies that we had designed to provide resilience. This had never been done in this area before, which made it difficult to explain to people why it had to be done in that particular way. I began by making a sketch of one room. The design was meant to be incremental – starting with one room to provide immediate shelter, then adding on a second room or a veranda. At the same time, the only materials we had access to were stone and timber joists reclaimed from the debris to which I added lime, having learnt its value while conserving Lahore Fort World Heritage. I would make the sketches with basic room sizes, but then I had to stand there and make adjustments depending on what was available.

I worked in this area for about several months (moving away only when countywide floods struck in 2010), but because everything had more or less collapsed or was declared dangerous because of cracks in the structure, there were few safe places to stay. Each day I made the 2–3-hour commute, driving through the hills where you never knew when a landslide might happen. There were tremors for weeks following the earthquake. I had no funding to do any of this, but my husband had spared 500,000 rupees (about £5,000), and I was lucky to get a lot of volunteers – students and other architects – from Pakistan and abroad who came to help. There were maybe 50 or 70 villages all isolated on different hilltops (in an area 5000 ft above sea level). We divided ourselves into teams and travelled to the villages to carry out the work. In 2006, I set up a base camp on a hilly 6-acre lot amid pine trees which allowed us to continue to experiment with different kinds of materials and structures for seismic-resistant construction.

As a child I never really knew what real Pakistan was. I grew up in a very pampered and isolated manner because my father had worked for the British government as a civil servant. After independence in 1947, when Pakistan became a sovereign state, we continued to have those privileges. We were only allowed to move within an elite social circle, and never permitted to go into old parts of the city.

When I moved to England and went to study at Oxford Brookes, I was taught how to be a prima-donna architect. I returned to Pakistan to make ‘starchitecture’ for elite clients, building in cement, glass and steel. My Finance and Trade Centre (1989) in Karachi was the largest building in Pakistan for a time, and I am could be considered the country’s biggest culprit of high-carbon construction. But my husband, historian Suhail Zaheer Lari, is a great photographer, and we used to travel to different places and old medieval towns in the country. These trips opened my eyes and inspired me to think about what I needed to do for Pakistan. I often talk about this period as my un-learning experience. In 2000 I decided that I didn’t want to carry on having a studio and pandering to the rich. Once I retired, I was invited by UNESCO to work as National Advisor for Lahore Fort World Heritage Site, and then the 2005 earthquake happened.

After the 7.6 Richter scale earthquake, I went from one disaster to another, working more and more with women. Our society is very restrictive, and outsider men are not allowed to enter women’s quarters. Because there were often no women in relief teams after a disaster, no one could articulate how one-half of the population of these villages was being affected. But being a woman, I could talk to them, and to my horror, I learned that women had to survive the whole day without a toilet. You could only go out in the early morning before the prayers, or after the sunset prayers, behind the bushes.

I understood that I needed to work things out for them more than anything else. They were the ones who had no voice and had no chance of interaction. We asked what crafts they had practised before the earthquake that they had to give up, and it turned out that they were proficient in this amazing traditional beadwork. We created craft centres in the villages to enable them to start making bead products again. A group of them would gather at one house (dubbed mini craft centre) and make bead jewellery which they could then sell. When we started I wanted to have a big meeting with all of the women in the area. The army general who was in charge (the Pakistan Army was in charge of supervising relief work in the area) said ‘Ma’am, don’t you realise that no woman will ever come? They’re not allowed to go out of their houses.’ But then 300 women walked something like three hours to come to this meeting. That is the event that completely opened my eyes. I knew women were keen to restart their lives and needed a helping hand.

Of all of my work with women, the Pakistan chula project revealed something important to me. Traditionally a chula is an open-flame brick stove set on the floor. It is a horrible way of cooking – squatting on the ground in the dirt, breathing in smoke. In order to prevent the stove from being washed away during recurring flood disasters, I designed an earth-platform-based chula that allowed women to cook sitting on a clean, elevated surface. By training chula-barefoot-entrepreneurs, we have taught thousands of women how to build the chula (60,000 earthen Pakistan Chulah have been built to date, benefitting over 400,000 persons) and, amazingly, they started decorating them. In Pakistan pattern defines everyday life, it covers every surface – on utensils, walls, fabrics. Like the traditional rural structures, the chula are made of earth – a material the rural woman knows well – and so their stoves become canvases for self-expression. My designs evolved into something extraordinary, something personal to the maker and a work of art. Every chula becomes its own drawing.

I grew up in a family where, having been trained by the British ruling power my father was somewhat anglicised, and in the colonial mindset anything local was not considered of value. It just happened that in contrast, my mother was extremely religious and believed in traditional values, so we grew up with two very different kinds of beliefs. There was something within me that related me to the soil, but I was not at all aware of what existed in terms of my cultural roots. Ironically, it was while studying in England that I became familiar with cultural traditions in Pakistan. In the nineteenth century the British had done a phenomenal amount of documentation on sub-continental architecture. I don’t think that after Independence we have been able to match the work those scholars had done in the late nineteenth century. For example, Henry Cousins compiled a book on the patterns of the ceramic glazed tiles (kashi) that decorate our sixteenth to eighteenth-century monuments in Sindh. The British left us amazing documentation that we can use, and I often refer to it. And so I have been lucky to experience my heritage and culture from two sides – one a more academic recording of traditions by the British, and then through these on-site experiences of the women living the decorative tradition. I don’t think you’d find another person in my country who has experienced all this. I cannot tell you how many doors opened for me once I gave up my architectural practice.

This interview was done with Helen Thomas. Drawn Closer is a year-long collaboration between Domus and Drawing Matter, edited by Sarah Handelman. Each issue of the magazine features one architect discussing a drawing which they recognise as a transformative moment in their work. This text appears in the April issue. Domus 2020 is guest-edited by David Chipperfield.