On Drawing

When I was very young I wanted to be an artist; I wanted to be a painter, and I started making paintings. Quite successfully: once, I sold a painting and bought a Fiat Cinquecento with this money. Impossible for me now, even if I complete a fairly big project. But I thought that painting was not socially relevant, so I decided to become an architect … because the idea was to set up a new world that was utopian, at a young age.

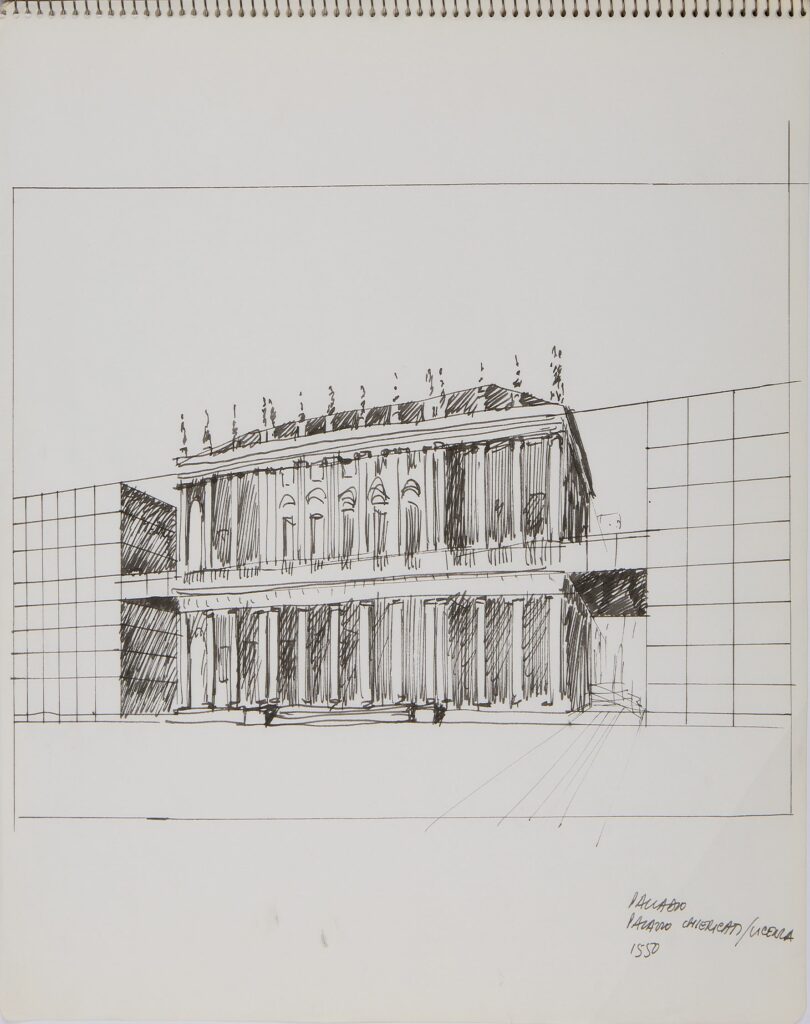

And so I graduated in architecture, but I was still involved in art, and as soon as I became an architect, I found no opportunity to build anything. Piranesi wrote once that he was forced to use drawing, because there was no other hope to build anything: okay, we were in exactly the same position. My generation in Italy had many talented architects, but none of us could ever build anything. So I started working with some friends in a group called Superstudio, in 1966 – which means … half a century ago! Well, and what did we do half a century ago? We were making drawings, mainly; we were writing quite a lot, in magazines, and we were teaching.

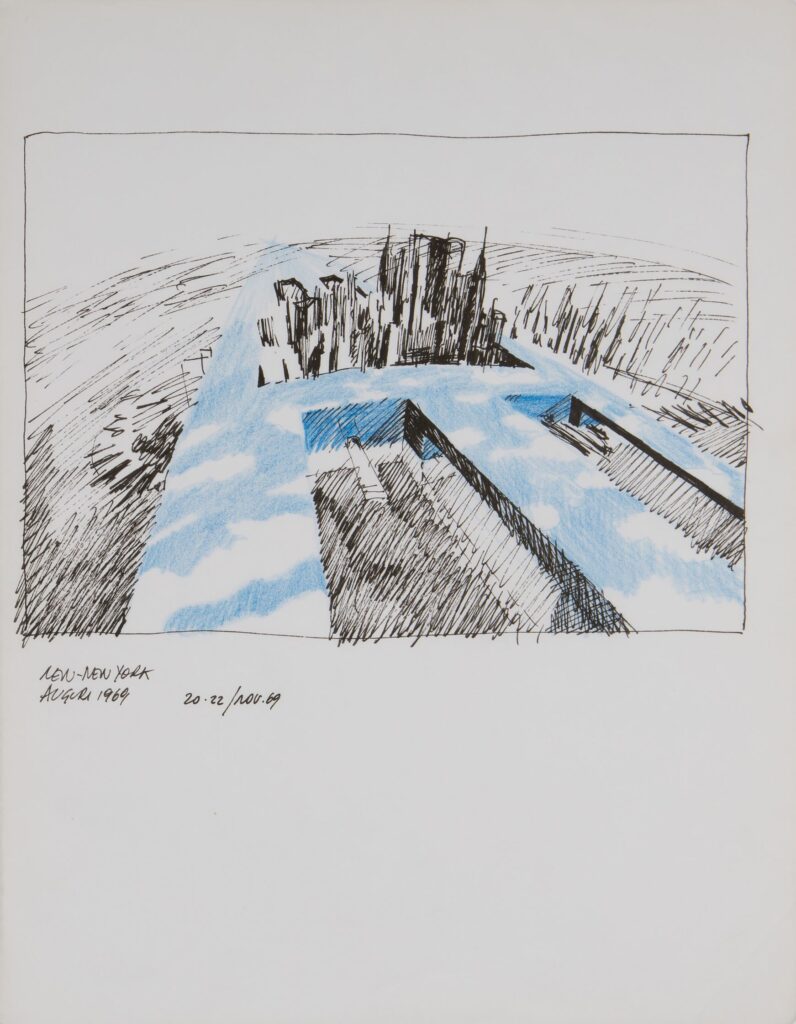

And the drawings, which are now in several different museums, from the MoMA in New York to the Pompidou, were only an expression, an illustration of some, let’s say, political manifesto. We had the intention to change the world; we had the intention to make revolution. But it was quite difficult, we found out, to make a revolution in the world. So we thought, well, maybe we can try and make a revolution in architecture, something much more limited. So we tried to do … something, which is now totally impossible to understand. Because if you separate the images from the writings, or if you separate the images from the context, it’s quite difficult to understand. [So the studio was, for radical architecture, a sort of Situationist movement.] What we did was a reaction to the present scene, a reaction against the International Style, against globalisation which was itself at the beginning, and so on.

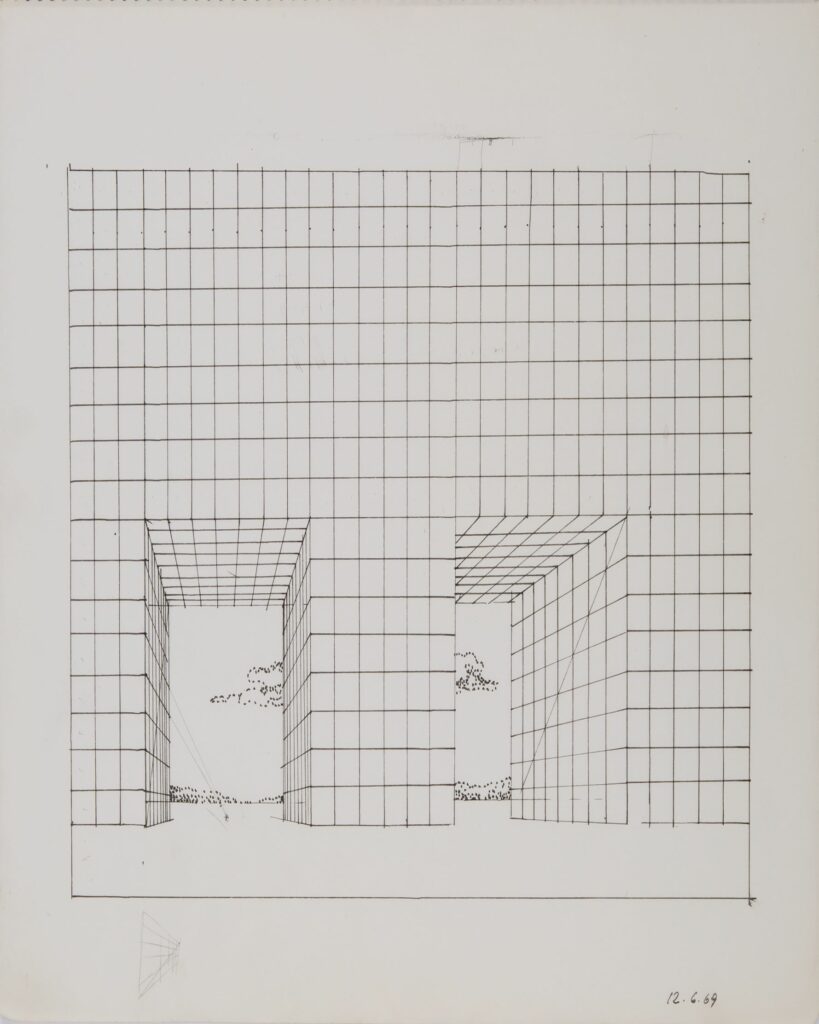

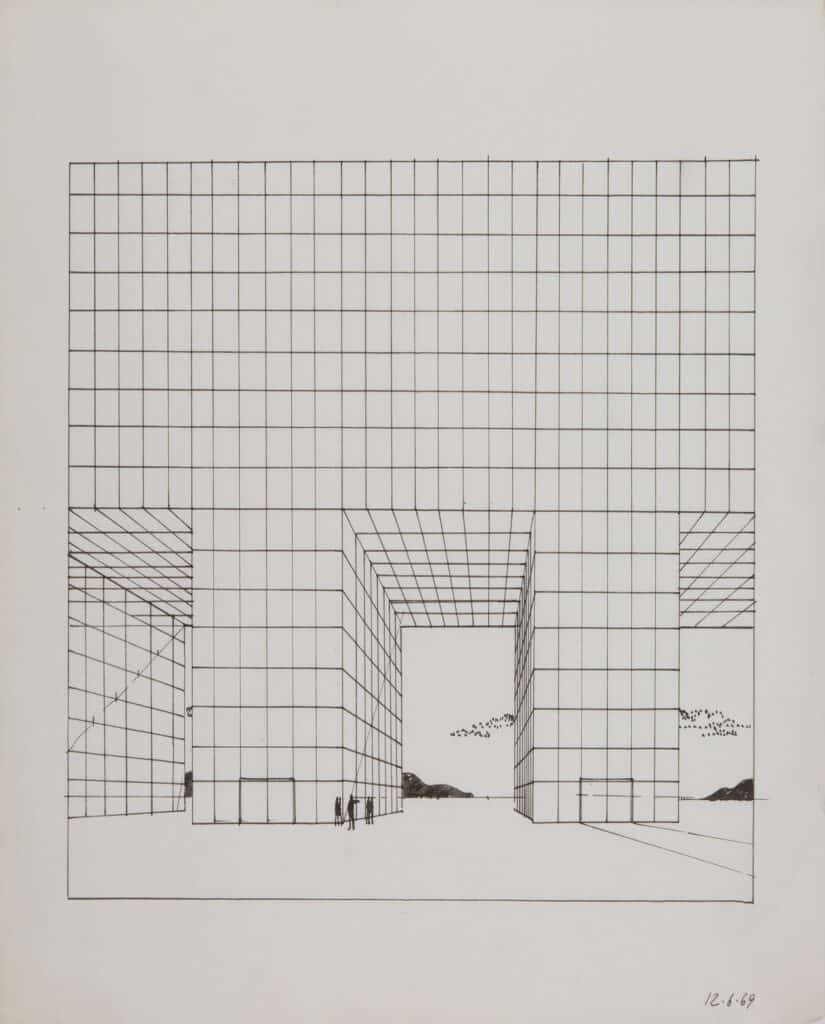

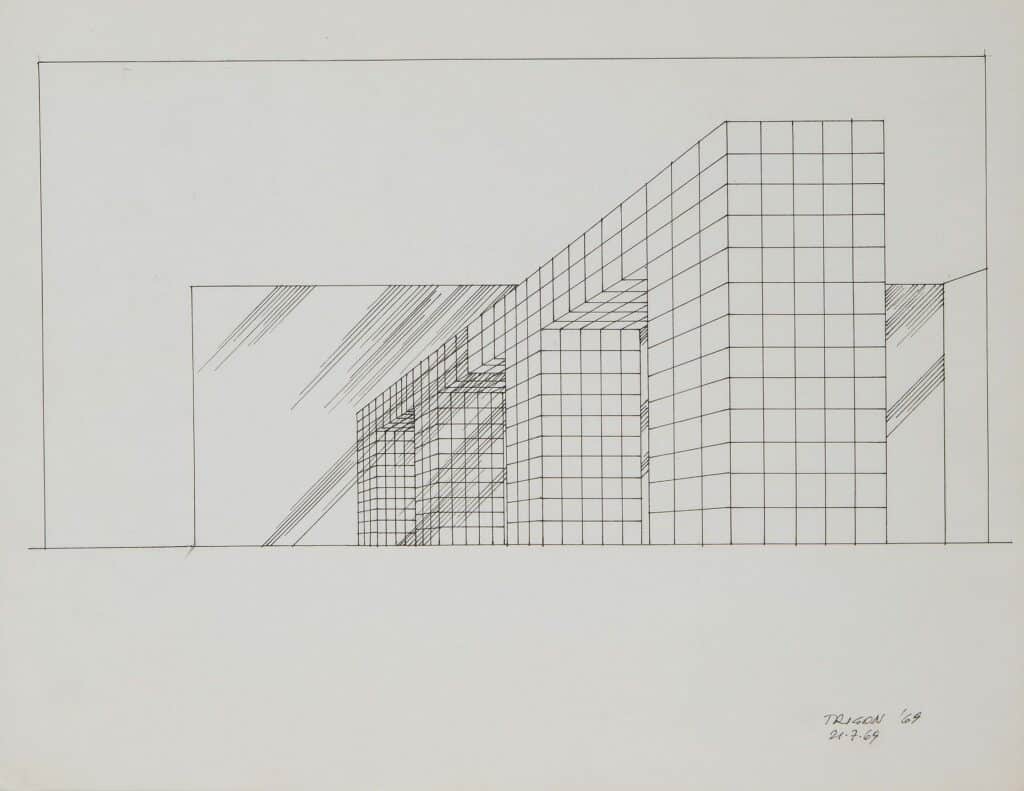

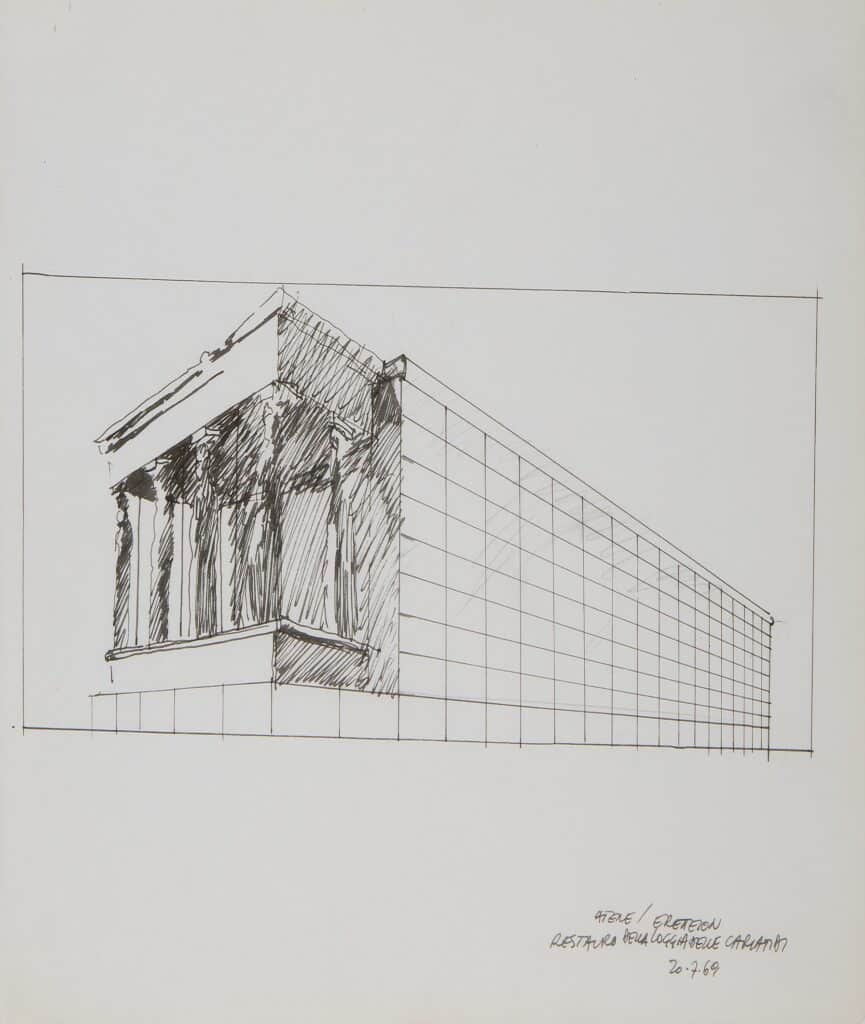

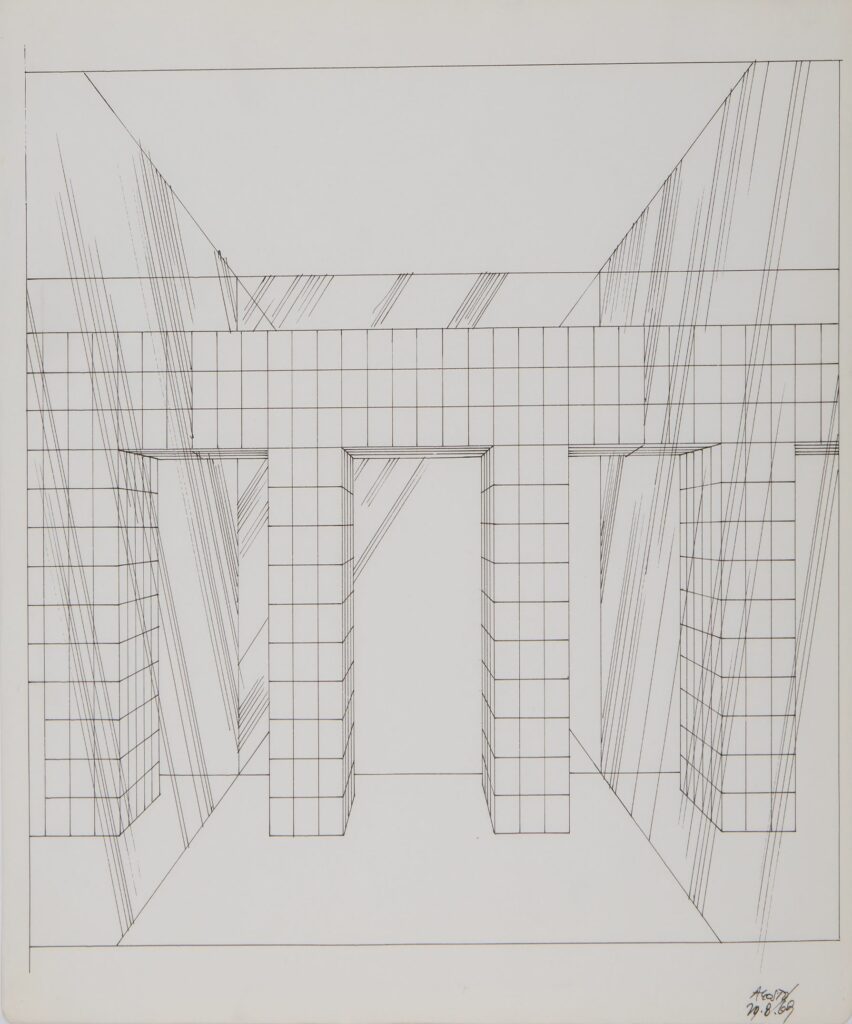

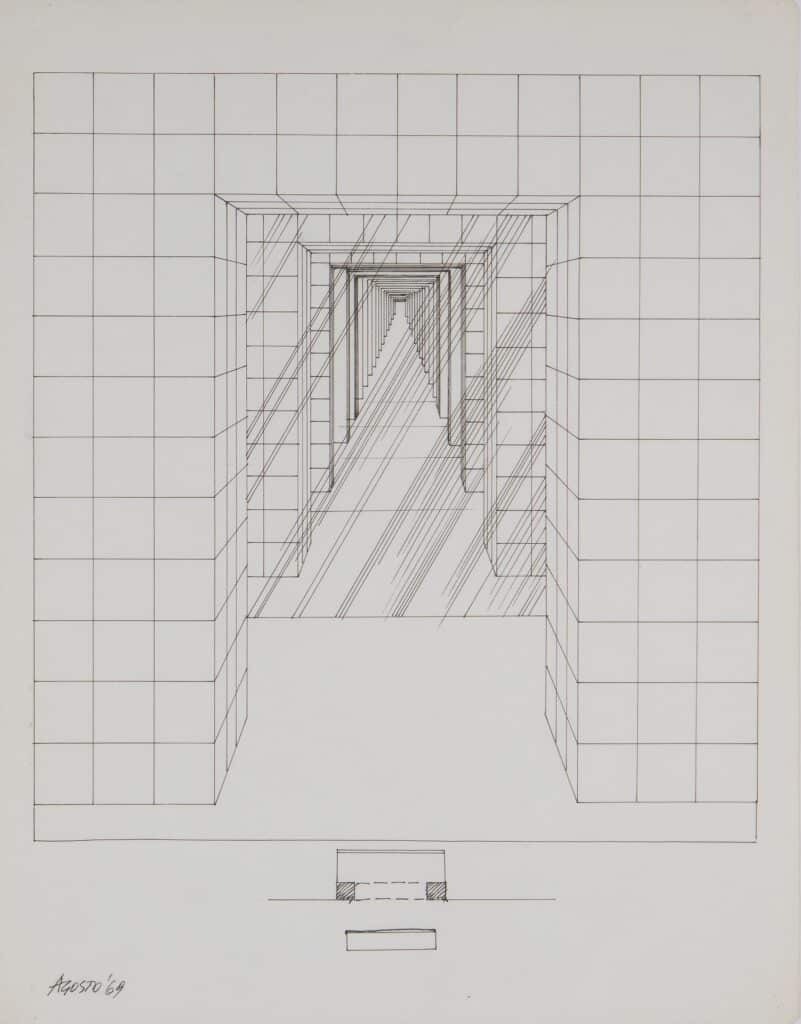

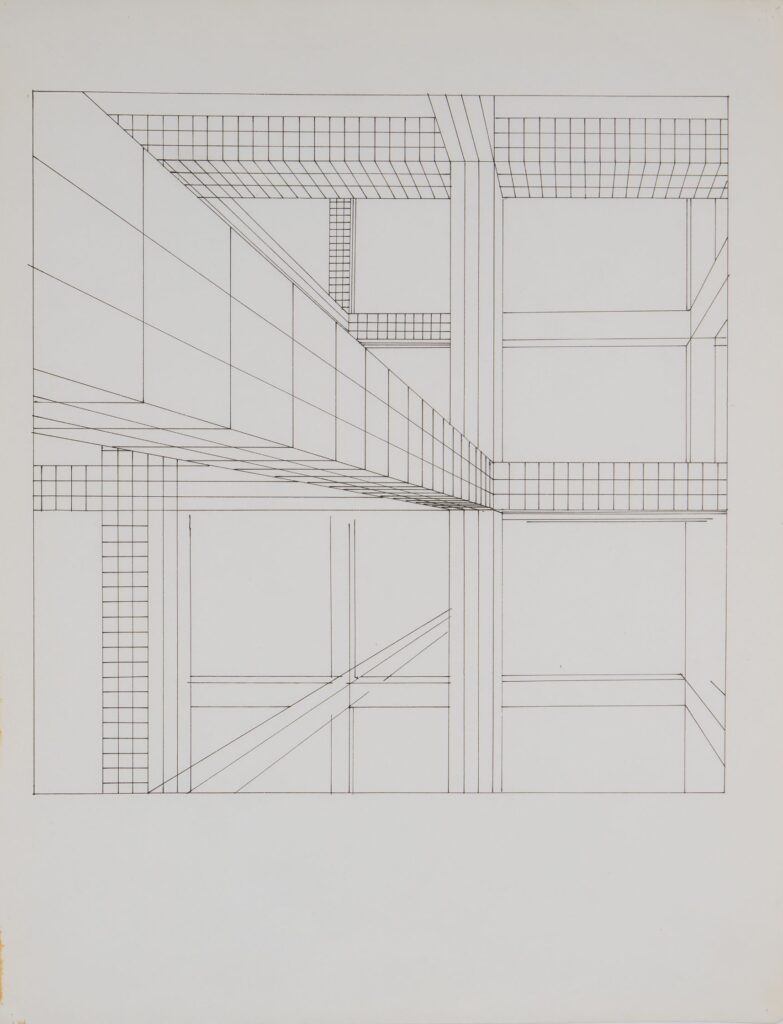

We did use a lot of artistic media, drawings collage, that sort of thing, and also a lot of rhetorical devices, like demonstratio per absurdum, the paradox, utopian irony and so on. For example, some of the things in my sketchbooks show a really typical project called the Continuous Monument. The Monument was a demonstration of the falsity and the absurdity of some of the theories that went on in that period. For example, one theory was that technology will solve everything. We will be able to make bigger and bigger monuments, we can build highways that reach more places, we are able to go to the moon … the idea was about the monument as a possible image for society, the symbolism. So on one side there was the beginning of high-tech, and on the other side something like Aldo Rossi, just to be very clear. We thought, okay, let’s try to combine these two things: we can think about a technology that can enable us to make enormous monuments, something which will be able to go all around the world. We started producing images of this sort of continuous monument, the continuous strip of urbanisation which was going around the world. And that was compared with the beautiful landscapes, the real cities and so on. In our idea, this image was the image of a sort of disaster that was coming out of these things. Now this image is seen as a very nice utopian image because the reality surpassed our fears, or fantasies.

Well, in fact we were not utopian, we were not utopists, we were using the anti-utopian as a sort of rhetorical device. And we did produce a lot of similar projects, like the Twelve Ideal Cities or the Continuous Monument, and slowly we started to get involved in another sort of investigation, let’s say, between architecture and anthropology. We started studying the popular culture, the production of architecture without architects, that sort of thing. We did stop producing drawings, but we started making more didactic materials – books, manuals, handbooks and producing movies. We did produce movies about human behaviour, confronted with Life, Death, Love, Ceremony and so on. After this period, we found ourselves old enough to stop researching and studying, and we tried a different way of [negotiating] the small changes in the world. I tried to be an architect; some others tried a different career, some disappeared and others became teachers. So after this Superstudio time, I was trying to become an architect building things in Italy and other countries like Germany and the Netherlands – so what I am doing now is completely different from when I made these drawings.

But in a certain way it’s the same thing, because what I have been doing for the past twenty years – mainly in the Netherlands, where I have been working in twenty-five different cities – is a sort of contemporary traditionalism. I am very interested in the local language; I think architecture has more to do with agriculture than with design. Design is something totally alien to architecture: if you are a designer you design a car, let’s say a beautiful Ferrari, and the Ferrari can go everywhere, from Canada to Kuwait: maybe they have something strange in the oil but it’s the same car, which is expensive, luxurious, beautiful and sexy. If you are making a highway, of course, it’s going to change if you have to cross a river or to cross a mountain. I think architecture has to do with the construction of roads in this sense: every architecture must be appropriate to the place, to the local culture and so on. So in the same way that, with Superstudio, we were making some sort of criticism towards globalisation and technology, so in architecture which is appropriate to the place there is a sort of criticism towards a new form of globalisation and all these kind of new utopias which are purely form. The present form of architecture is something which is totally alien to society, history. Everything, really. Present architecture, when I look in the magazines, is really something else: well, I have nothing to do with such a thing. Before, at the table we were talking about architecture from Vitruvius and architecture now … from Vitruvius we have learned that architecture must be solid, useful, beautiful, and maybe now with these things we have to add it has to stay together or coexist with other things. But now it seems the main idea of utopia is to make things different. So architecture must be not useful, ugly, or very expensive. This is the world.

So, architecture is something that is becoming totally detached from human society, and more and more like an abstract art – something which I am not able to understand anymore, but that is because I am getting very old. In any case I am very happy to be here and to see some of my old drawings together with drawings of very good friends, people whom I like very much. And I’m very proud to have my drawings shown near to such examples from Louis Kahn, or Le Corbusier – as a young guy I met both of them and I’m still very proud of that, but I haven’t had my drawings shown with them, until now – so I’m very grateful to the curators and to the gallery for that.

If we wanted a new revolution, could it begin again with irony as it did with my revolution in architecture? We have a very few good ways to be revolutionary, maybe one of them is irony I’m not sure anymore. But nevertheless, I remember as a young guy working on an exhibition of Le Corbusier in 1964, just one year before he died. We were putting his beautiful drawings and models on the wall. Le Corbusier was there and he was going around taking off his drawings and putting there his paintings. He thought his paintings were much more relevant than the drawings. He said well, the secret of creativity is this one, architecture is coming afterward. At that moment I was not able to understand him but now I have the intuition that he was right.

– Adolfo Natalini, June 2015, at Hauser & Wirth Bruton, on the occasion of the Landmarks exhibition of architectural drawings and artefacts. Transcribed by Shumi Bose.

– Julian Lewis