Houses for Printing: A Microcosm of the World

The following text is an excerpt from the guide that accompanied the exhibition ‘PRINT READY DRAWINGS: Composites, Layers, and Paste-ups, 1950-1989’, installed at the MAK Center for Art and Architecture in Los Angeles between 11 November 2023 – 4 February 2024, and curated by Sarah Hearne.

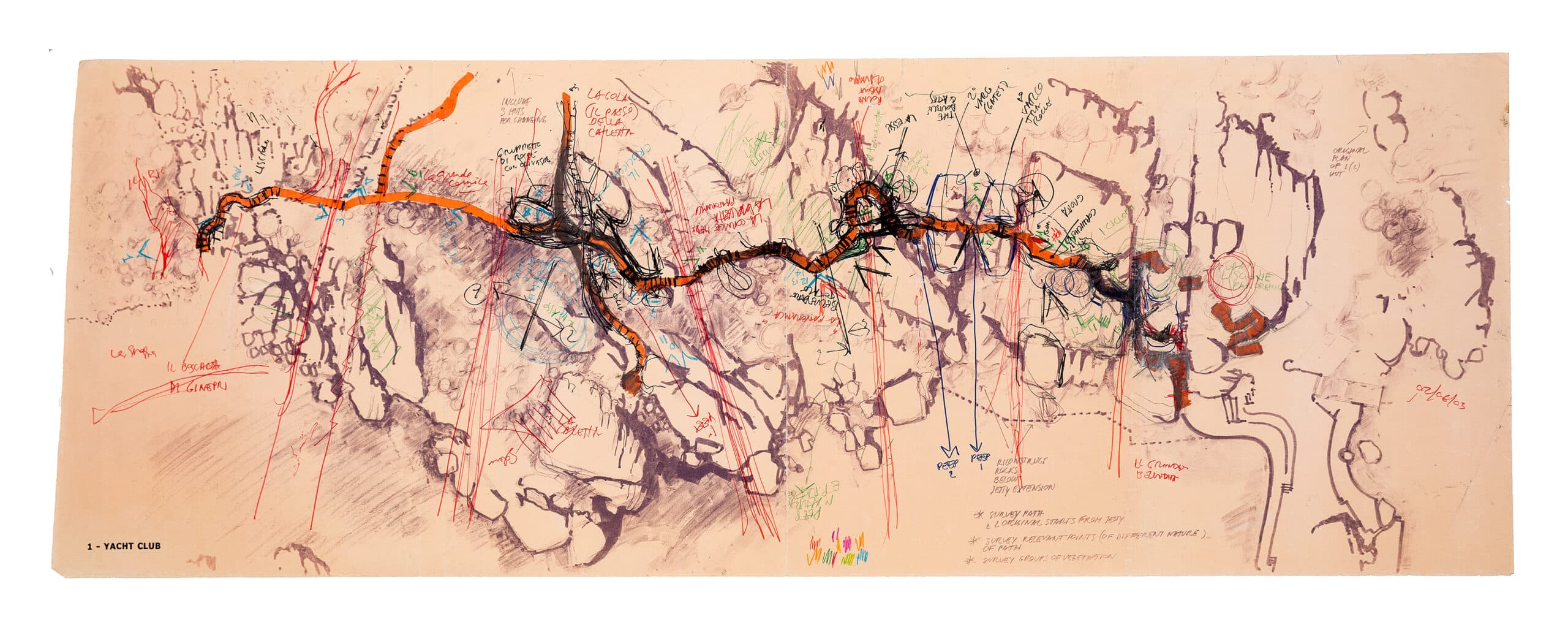

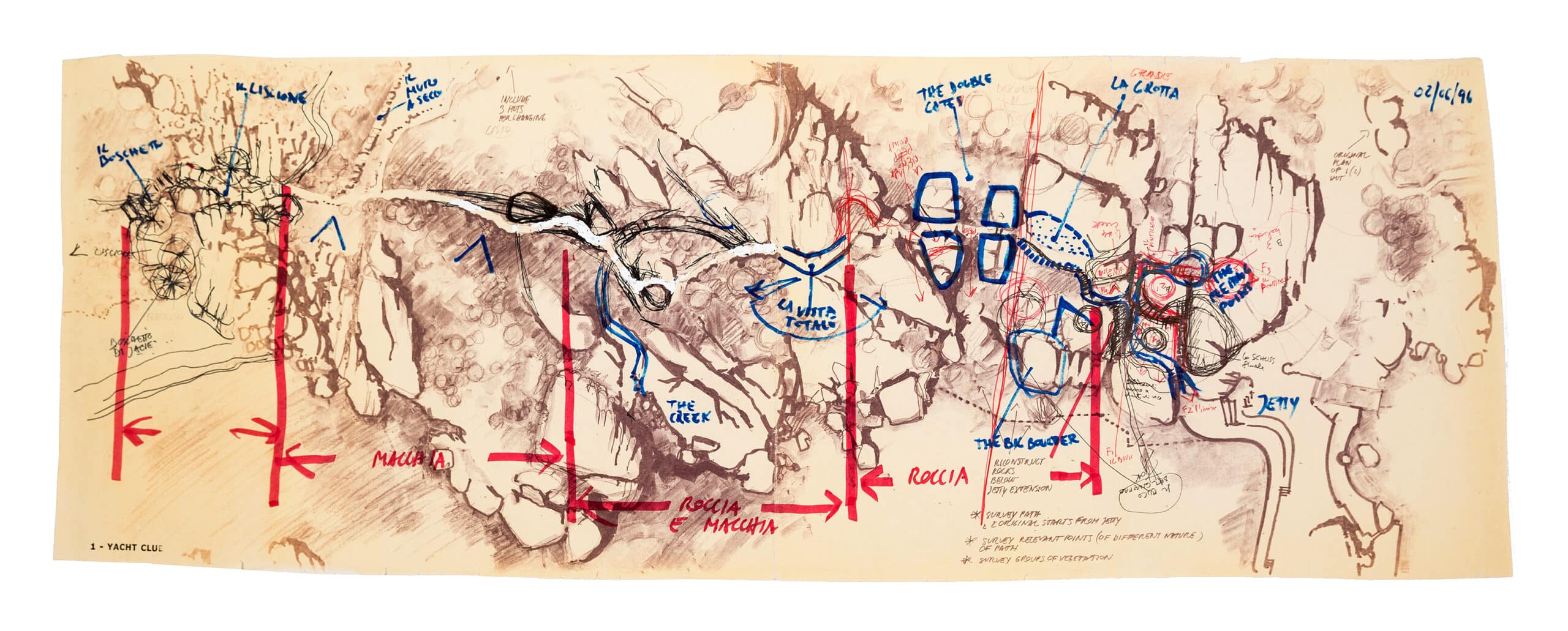

Caterina Pincioni, secretary at Alberto Ponis’ architectural office in Palau, Sardinia, described the context of printing at the peak of his activities developing the seaside tourist destination in 1970s. When Ponis joined fellow London-based designer of branded Italian restaurants, Enzo Apicella, to develop Punta Sardegna in Sardinia for British holidaymakers in early 1963, he began with a single house. The pathway to the Punta Sardegna Yacht Club, which is depicted in the resulting diazo print drawings, was laid out in situ with surveyors. This line, printed in cement, was later recorded in an illustrated graphite survey, mapping rocky outcrops and overgrowths. By the 1980s, Ponis had designed over 100 houses for the region, with the diazo prints for each house developed in the office. Using heliographic processes required paper rolls to be imported from nearby Sassari, developed in ammonia under UV lighting, and suspended to dry on wall racks, with the vapours from the process mitigated by opening the office to the coastal Sardinian air, which was central to Ponis’ phenomenological understanding of a natural and unspoiled regional site, flora, and climate. The Yacht Club Pathway prints were made from this initial study and marked with in situ observations of the site. He has described these overlayed diazo prints as a ‘report,’ a term that suggests a coming after, and a form of documentation. These items, creased to be folded into pockets and speckled with watermarks during site visits in the rain, retain the evidence of their utility.

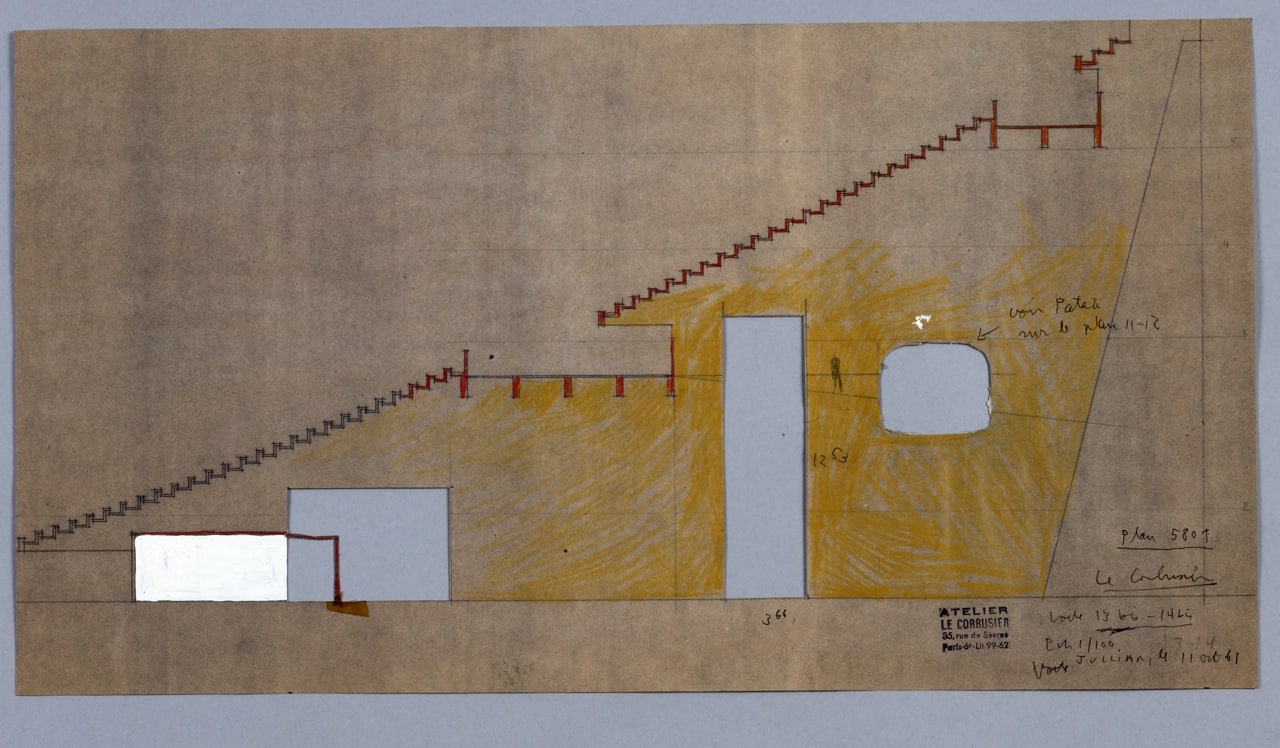

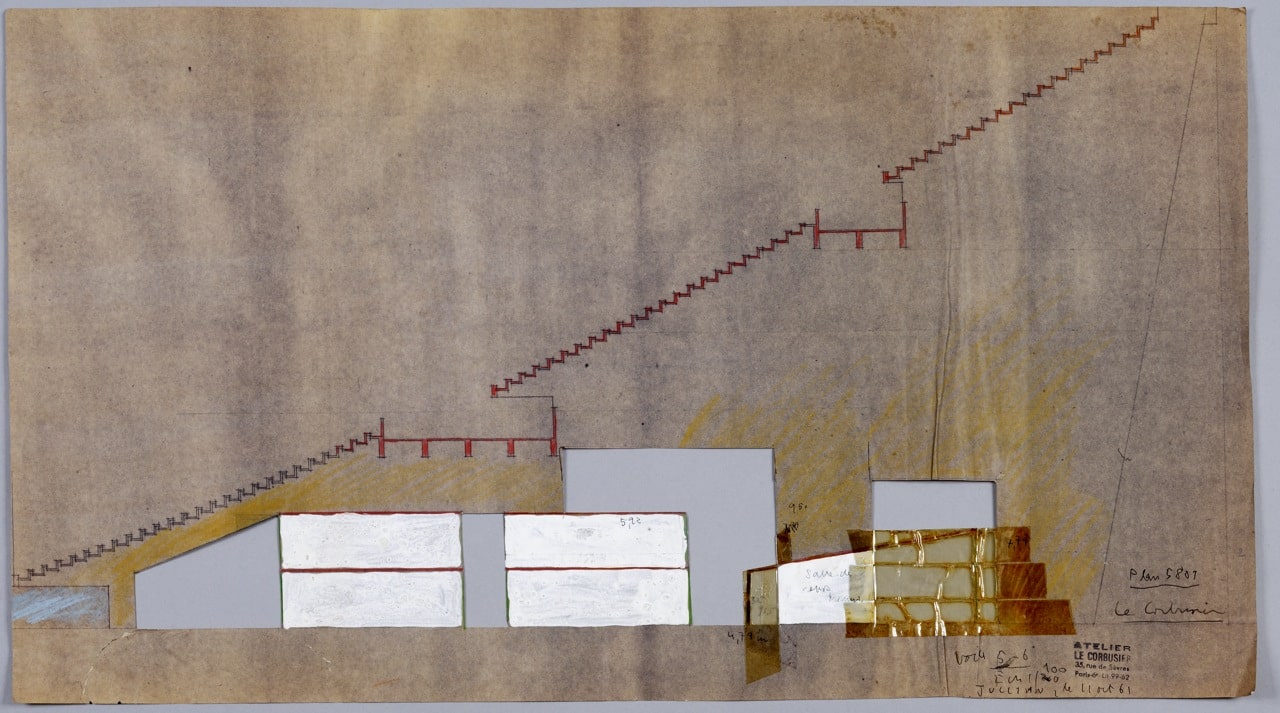

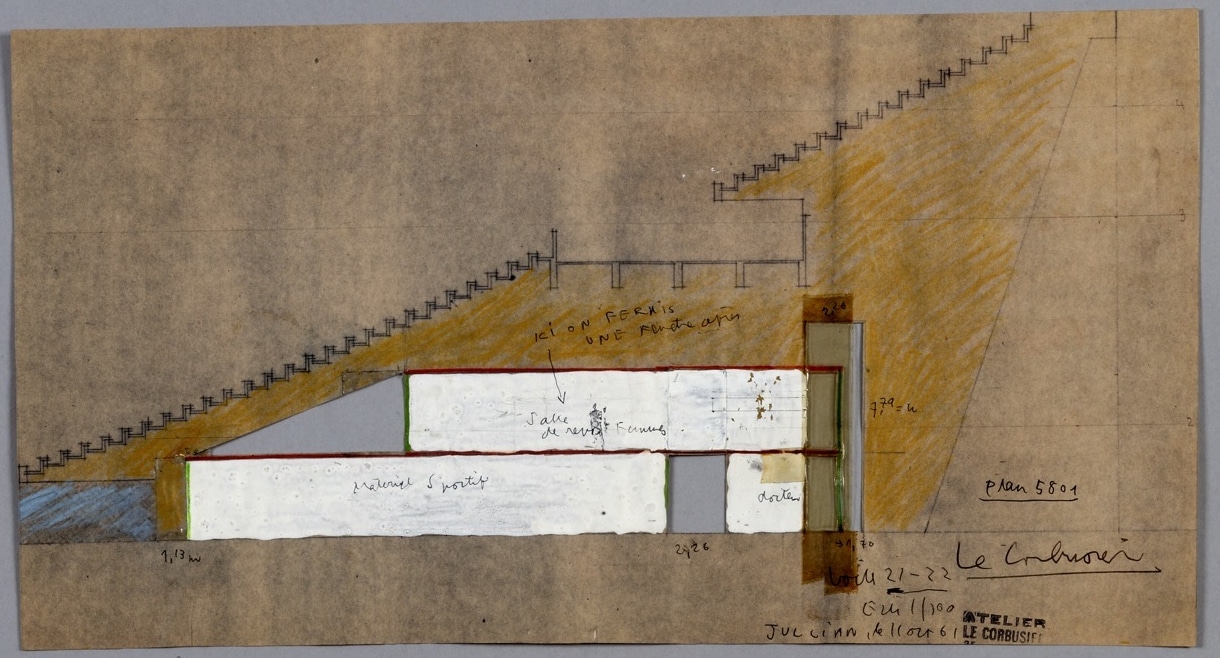

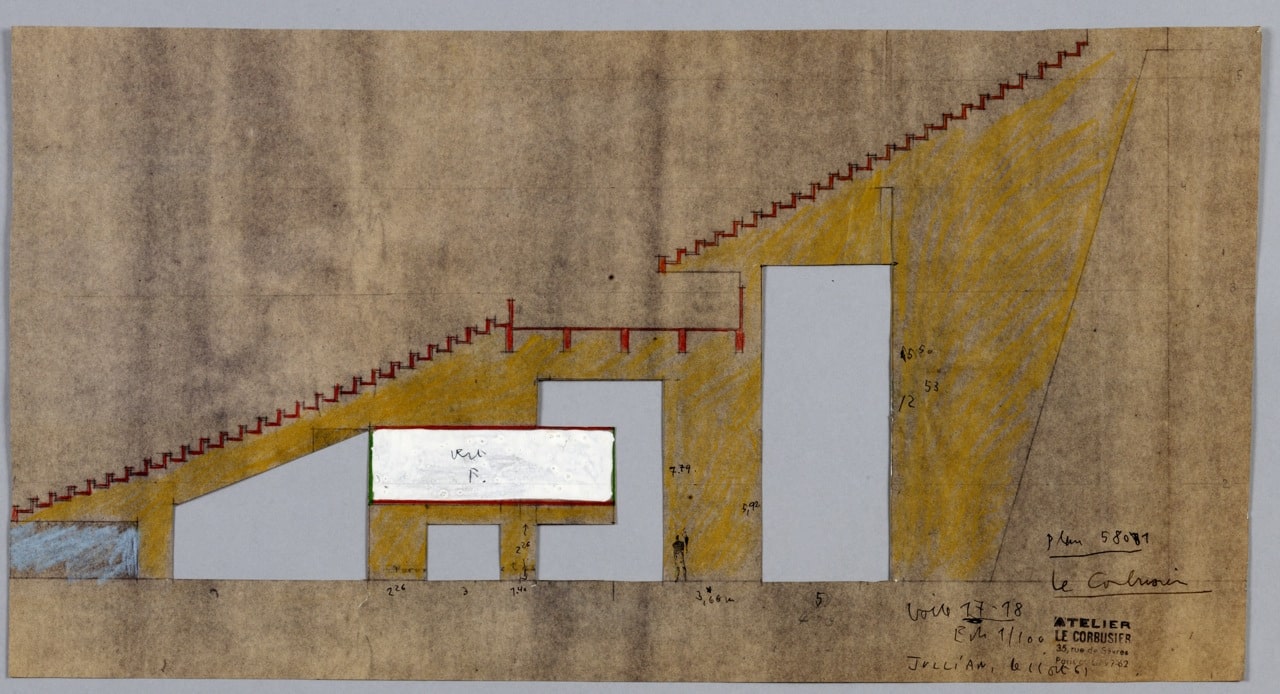

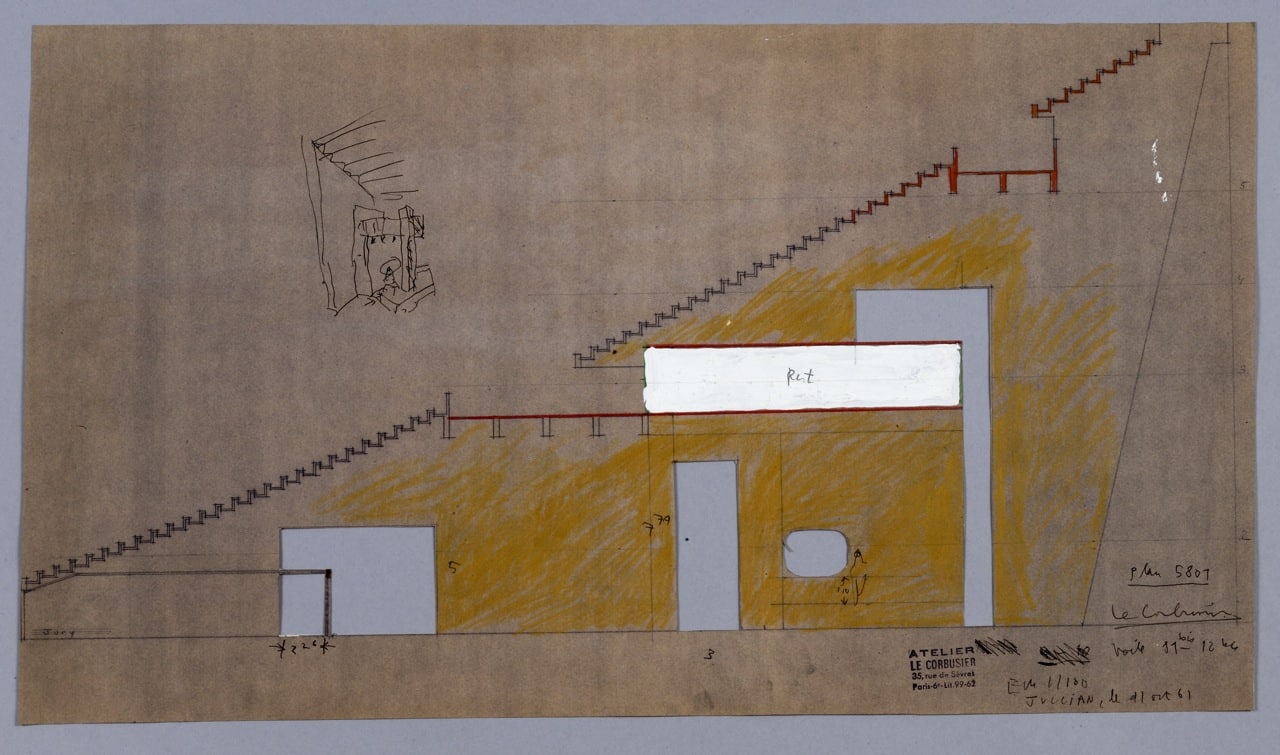

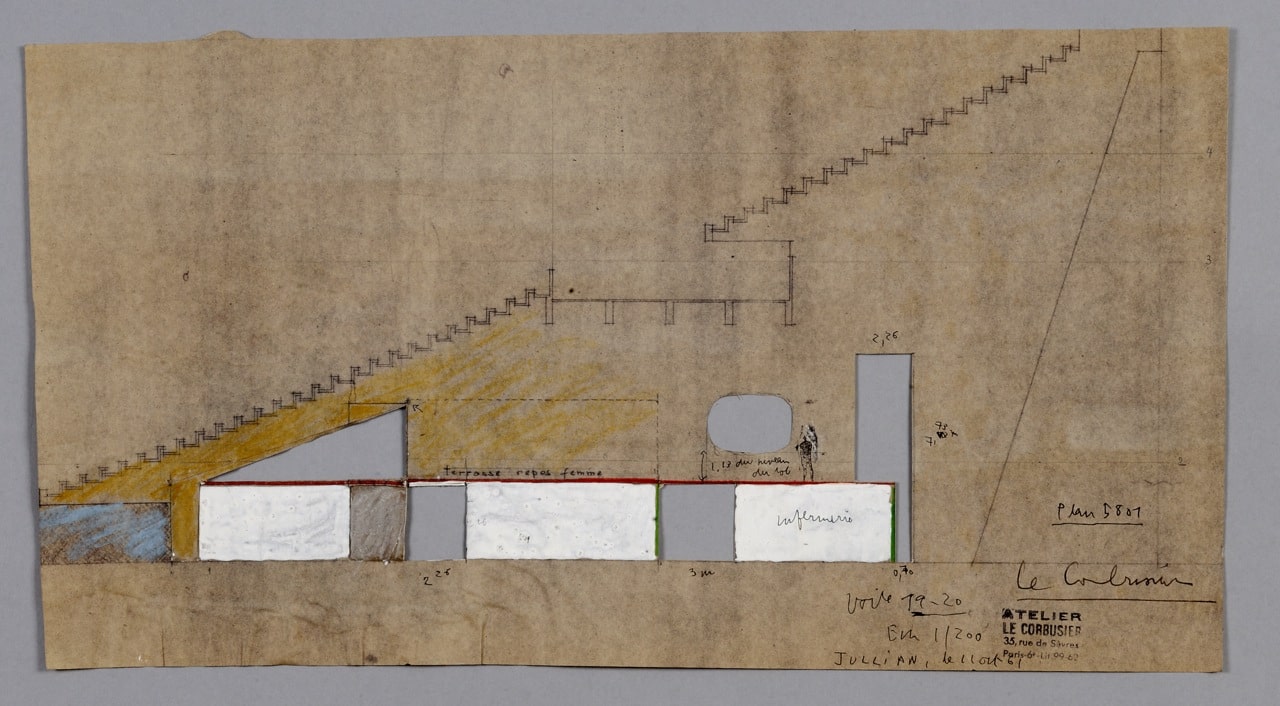

In designing a new stadium in Baghdad between 1955 and 1964, drawings crossed between the atelier of Le Corbusier at 35 Rue des Sevres and 66 Avenue Kléber which housed the technical wing of his office and the engineering office of Georges-Marc Présenté who consulted on the project. The section displayed here is one of a series of sections describing the ‘veils,’ or structural fins that fanned out in plan to support the stadium and seating and to conceal service spaces. The diazo-printed base of the document has been altered with cut-outs, overlays of crayon and white paint to conceal areas of alteration. These were produced in the atelier by Guillaume Jullian de la Fuente. The discussion around authorship of the Baghdad Stadium centralizes the spaces of production in narratives that mythologize the protection of hands touching the drawings and the maintenance of direct contact with Corbusier and his supervision. This was a project that originated coincidentally with a labour dispute in the office and a reorganization of spaces and staff. Fuente’s special role on the project is mythologized in relation to Le Corbusier changing the entry locks to Rue des Sevres as a means of expunging the previous office staff, stemming from a pay and credit complaint. This left Fuente as one of the only remaining assistants during the project’s three-month design development in the atelier.[1] A preamble in the meeting minutes from November 9, 1961 referred to a need to clarify ‘the situation’ between these two offices, suggesting that the separation was at times producing misalignments.

An examination of the relationship of drawings crossing Paris reflects a broader picture of contributions between the design and technical sides that circulated around the drawings. The separation of these realms of work in Le Corbusier’s office has been well documented. It was also a separation registered in the drawings circulating between them: in the materials related to the design of the Baghdad Stadium Fuente’s contributions were often collaged with coloured craft paper, testing the sectional qualities of the veils with cut-out areas. These documents were exploratory, and their duplication is explained in relationship to an iterative process of testing more aligned with the spontaneity of intuition and creativity. While the effort here was to distinguish the creative with the merely informational and technical, material manufacturers of duplicative processes and photographic drafting papers, of which there were a multitude by the 1960s, were investing in the possibility of drawing systems that followed a similar logic. These reproduction technologies problematized the notion of original, with terms like ‘reproducible reproduction,’ ‘intermediate master,’ and ‘second originals’— terms that no longer fit simple categorization and instead foreshadowed the digital terminology of versions.[2] Returning from this destabilized point of view to the Baghdad documents, we might consider the ways that reprographic techniques were found across both spaces, alongside the appearance of collage that occurred in documents that calculated technical information such as spatial capacities and dimensions pasted as coloured boxes onto the program brief. These overlaps complicate the efforts to maintain distinctions between the offices and the nature of the work that was produced in them.

Notes

- Fuente’s wife Ann Pendleton’s account of this event is found in the papers at Drawing Matter. Karen Michel describes this event as a labour dispute in 1958 in which staff were fired for asking for better compensation and credit, and they were replaced with Guillaume Jullian de la Fuente, José R. Oubrerie, and Arvind Taves. See Karen Michels, Der Sinn Der Unordnung: Arbeitsformen Im Atelier Le Corbusier (Braunschweig: Vieweg & Sohn, 1989), 42.

- ‘The intermediate master or reproducible copy encourages improvisation. The designer can make any number of duplicates, plans, elevations, and can sketch alternative suggestions on these.’ Brunning Company. Copying Technology, Practicing Architecture Section (July 1963), 145.

Sarah Hearne is an architectural historian, educator, and curator. She received her PhD in Architectural History at the University of California Los Angeles in 2020 with her dissertation ‘Other Things Visible on Paper: Architectural Writing and Imaging Craftsmanship 1960-87’.

‘Print Ready Drawings’ is curated by Sarah Hearne, with curatorial assistance by Arianna Borromeo, Lauren Akira Verdine, and support from the MAK Center exhibitions team Seymour Polatin, Exhibitions and Programs Manager and Brian Taylor, Curatorial Assistant. The exhibition features commissioned films by Julie Riley and Jenny Leavitt. Exhibition design is by Current Interests with conservation support from Paradise Framing. Graphic design is by Christina Huang. ‘Print Ready Drawings’ was made possible, in part, with generous support from the Getty Foundation’s Paper Project Series. Additional support was provided by the Graham Foundation for Advanced Studies in the Fine Arts and the University of Colorado Denver, College of Architecture and Planning.