In Search of an Honest Map

We don’t experience place as maps would have us believe. We might technically exist within the map, an orientation marker besieged by the total sum of data, every landmark, park and street swarming around us at all times. But our perspective is only partial – a patchwork of neighbourhoods, structures and scrambled place names linked by personal memory and emotion, rather than historical or geographical significance.

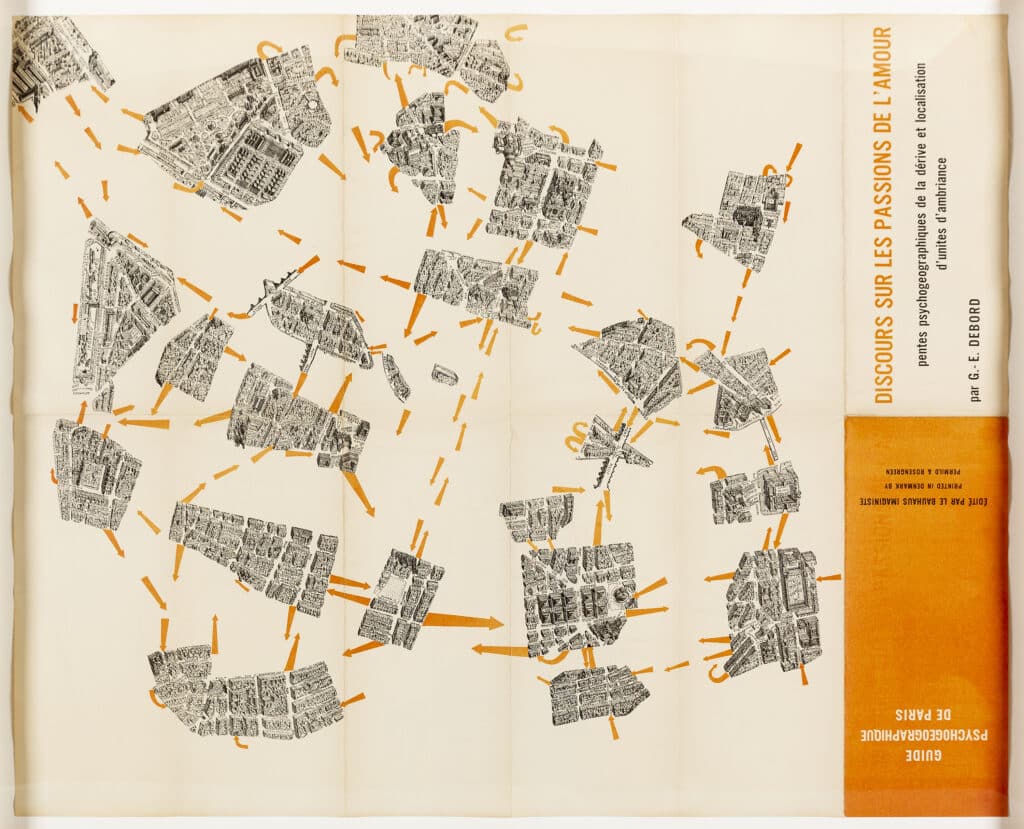

Guy Debord’s 1957 work, Guide psychogéographique de Paris, is the truest representation of our relationship to place I’ve found. The map can’t be called accurate, and barely includes any data, but it is honest. G. Peltier’s map of the capital has been defaced, chopped up chunks chucked back in a random assortment. The city’s scaffolding is erased, bright arrows threading through the space – a fortified hive reduced to the most delicate of cobwebs. Debord created the work as a rejection of rational, functional city planning – a Situationist experiment to inspire more playful interactions with our surroundings, encouraging the dérive, or ‘drift’: aimless, unplanned explorations of an urban landscape, navigated by chance and emotion.

Out of context, Debord’s map is a drawing that could depict our limited perception of place. In each of our heads is a different map, unique archipelagos of seemingly random locations linked only tentatively or floating in isolation. We travel blindly around these islands, often unaware of the distance in-between. London is an extreme example – the effect of the underground is such that the city’s connective tissue, as in Debord’s map, is stripped away. One descends at Point A and ascends at Point B, the journey just darkness and noise. Though I spent four years living in London, I left with an incomplete understanding of how its significant areas – and the areas significant to me – were connected. An inextricable element of anyone’s idea of London (except perhaps a London cabbie) is the network of voids running through it.

I lived in Bath for over five years, and though the city is small and doesn’t possess a subway, voids are present. There are streets I never walked down, neighbourhoods I never visited. There are landmarks, hazy, I had no interest in, and places that stood out more than they would to someone else: the bench above the golf course, the lane behind the Circus, St. Stephen’s Millennium Green.

The COVID-19 lockdown provided me with an opportunity to discover more islands and draw new arrows between them. In the first weeks of the crisis, the strict limits imposed by our government-allotted exercise time meant that my usual walks and connections quickly became stale. I wasn’t walking – I was trudging trenches into my map, the streets becoming treadmills rather than routes through an environment. Slowly, I began to deviate, unknowingly practicing Debord’s dérive, drifting without aim around the city I thought I knew. I started walking with my camera, navigating not by habit or convenience, but by connecting the dots between potential photographs, hopping from shot to shot. With each picture, my map of Bath – the private, not the learned – began to grow.

Guide psychogéographique de Paris challenged me to think about other, more honest, ways we can map our surroundings. I considered making a photographic collage organised by geographical coordinates – a mapless map that better represents my idiosyncratic Bath, all the extraneous bits lopped off. Or superimposing the photographs onto an existing map I could share with others, interrogating their idea of the city, shrinking the space between their islands.

As I went through the photographs taken during this time, I became aware of a pattern, an unusual perspective: I was looking upwards. Victorian advertisements on buildings; a rare vapour trail; a copper beech against a blue sky; the labyrinthine canopy of a plane tree. It wasn’t clear if this viewpoint was another reaction to repetition, an attempt to see the city afresh, or if it was representative of an urge to escape the confines of lockdown. The pictures prompted me to think about the accepted cartographical perspective, and its inherent dishonesty. The bird’s eye view is unnatural – I live on the ground, I have never experienced my home from above. Just as G. Peltier’s drawing, which Debord defaced, tilts downwards in an attempt to make the city more familiar, I wondered if a map could be drawn not with an aerial view but a terrestrial one. After all, it’s not birds who use maps, it’s people.

Not found in cartography, the worm’s eye view is a perspective employed in architectural drawing to show certain features that might otherwise be hidden. Notably it can be seen in Auguste Choisy’s vaulted ceilings, and in Stan Allen’s drawings of the Merida Museum for Rafael Moneo, Alfred Arndt’s colour plan for the exterior of the Bauhaus Masters’ Houses in Dessau, [1] and in Hugh Strange Architects’ designs for the Drawing Matter archive. James Stirling, Michael Wilford and Associates often used worm’s eye axonometrics as ‘a method of showing off dexterity in drawing skills’. [2] It’s a perspective so strange in illustration, so foreign to the eye, that outside of their architectural context, these drawings read more like M. C. Escher creations than technical designs.

Would it be possible to produce a map from this perspective, and would it be more honest? A map that represents the way we actually experience the world, instead of some disembodied, omniscient depiction? Would the map defamiliarise our environment, allowing us to become more observant? Would the map inspire new ways to interact with the city, or trap us in an impossible, Escher-esque illusion?

The suggestion is clearly unfeasible and possibly even a little mad, but perhaps no more unfeasible or mad than Debord’s abstract reimagining of Paris. His map, though entirely inaccurate, and far from functional, is a map that strives to be meaningful, urging us to experiment and play within our situation. Debord created a jumping-off point – a call for us to question our preconceptions of place. Guide psychogéographique de Paris feels refreshingly human, and though utterly unnavigable, can surely be called honest.

Notes

- Alfred Arndt, Master semidetached houses seen from below, 1926.

- Chris Dyson, ‘No house style: the drawings of Stirling and Wilford,’ Architects’ Journal, October 13, 2015.

Nicholas Herrmann is a writer, editor and film photographer, whose work explores place, identity and nature. nicholasherrmann.com

This text was entered into the Drawing Matter Writing Prize 2020. Click here to read the winning texts and more writing that was particularly enjoyed by the judges.