Drawing Without Erasing

The following text first appeared in Drawing without Erasing and Other Essays, by Flores & Prats (Barcelona: Puente editores, 2023), 16-23.

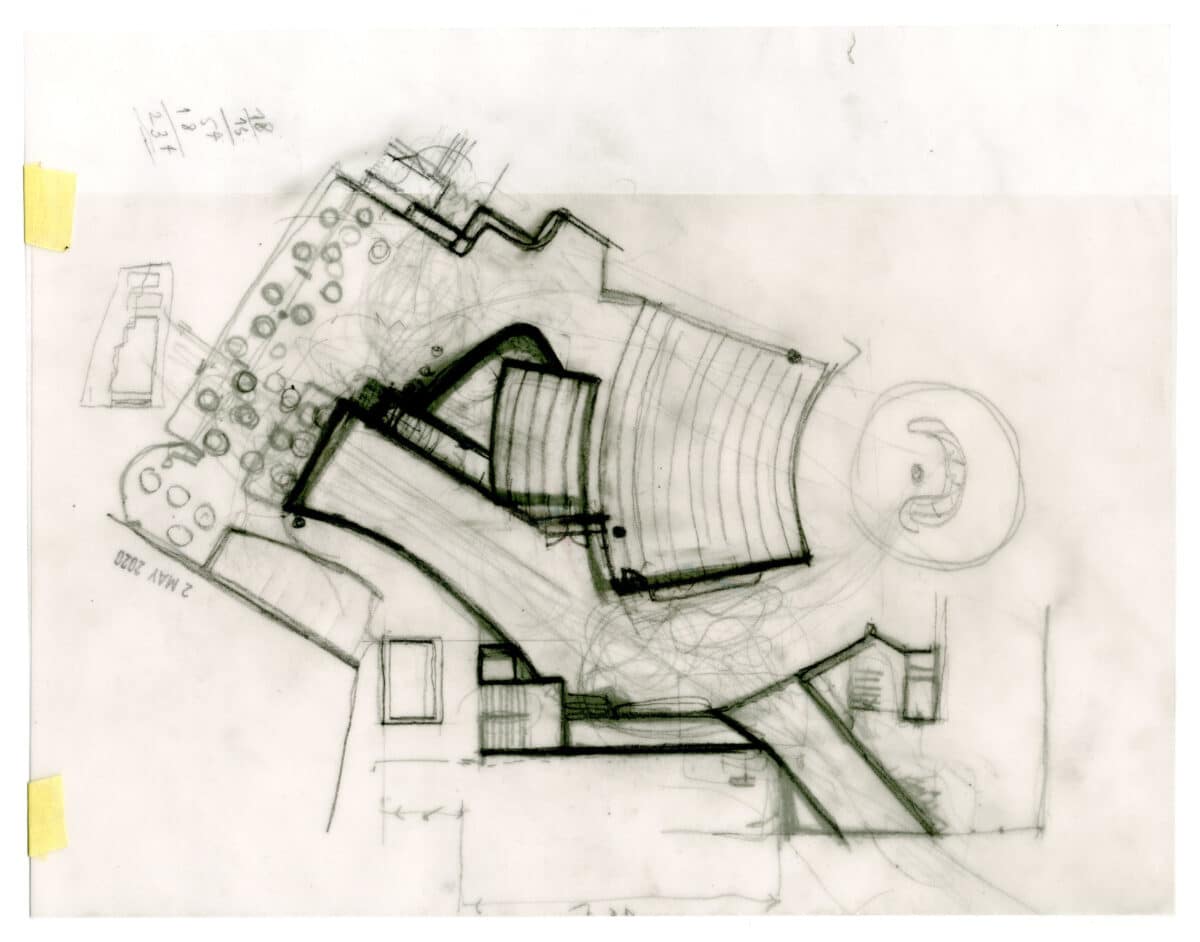

Not so long ago, a journalist interviewed us for the British magazine Architecture Today, and the resulting article was called ‘Dirty Drawings’. This suggestive title might bring to mind a range of different things, but it was in fact a direct translation of dibujos sucios, an expression we use in our studio to refer to the kind of drawings that buzz with ideas, with many lines drawn by many hands. That is, they’re not clean; they’re covered in clouds of smudgy graphite. These are not polished drawings to be presented—they come from our reflections on the projects, but they are still very useful because they show our concerns, our doubts, and all our comings-and-goings in drawn form. Normally, these drawings are not made public: they are created in the studio at certain moments, like when you’re in the middle of something, or when you start a discussion with a colleague or collaborator, and everybody’s drawing on the same piece of paper, and in this sense, they are the direct visual representation of conversations and exchanges like this. Sometimes, they are simply scanned and archived; they comprise a more private, intimate material to show and talk about later on. This is why that journalist was so interested in them.

Dirty Drawings

Our dirty drawings are done quickly, freehand, using soft-lead pencils. We draw on tracing paper, placed on top of a computer-drawn plan. By using tracing paper, you can focus on a specific point of the base drawing, rather than on the whole plan. This way, you can test things out quickly, to get things moving forward. ‘How do all these parts connect together? People will be at the bar, going up the steps, walking and crossing the space. This whole experience should be connected.’ You draw from one end to the other: people walking or looking around or asking for information, or perhaps they’re sitting and waiting on a bench. All of this should be a continuous sequence, like in the street, where so many things are going on simultaneously. Your hand knows how to include the tension that exists from one end of this street to the other: when your pencil moves, you are thinking, and your pencil comes with you. ‘Maybe a bench should go here?’ You and your pencil put your thoughts down on the paper. This drawing explains how all these elements, i.e. the bar, the steps, the corridor, the seats… should work together as one. We want people to meet by chance, and get to know each other; these kinds of situations are what make places like this so appealing. You can see the drawings getting freer as the drawer’s mind fires up. You draw and redraw without erasing anything, leaving several options on the overlapping sheets of tracing paper. This way, the drawings soon become a pile of variations and distortions of a flexible geometry that increasingly adapts to the place and to your ideas. At a certain point, you realise that you like one of these iterations so you stop and redraw it with greater precision in terms of intention, geometry, dimensions, and proportions. All of this material can usually be found spread over tables: it is the result of the architect’s day-to-day work.

The Desk

An architect’s desk is an interesting place; it is home to our partial or complete models and the books we’re into. We need to be surrounded by books, and their physical quality, so that we can look at them when stuck on a problem or when we’re tired of drawing. Opening a book is a good way to let your mind drift away for a while and enter into someone else’s world, where you can think over the issues with a project by looking at other people’s beautiful drawings. We let our eyes and minds wander over all the pages of the book, and this is why its physical condition is so important: it’s like a faithful companion, ever by your side. After looking at a book for a while, we get back to our own tasks. This is why, on our desks, there are books, process drawings, some sketches, tracing paper, and some handy work tools: set squares, pencils, cleaning brushes, a rubber, a sharpener, coloured pencils, a scale ruler for measuring, templates, masking tape, and many graphite pencils. It’s not unlike a building site; the builders keep their own tools close to hand, and they use them all the time.

We can draw with set squares, or we can use a parallel ruler for moving and drawing perpendicular lines. This ruler makes us work within orthogonal geometry, of parallel and perpendicular lines, while the set squares let us move across the paper with greater freedom. It is important to think about how the tools define the process, how they define a certain way of drawing, a way of constructing the document. To stop the paper from moving, we always use masking tape, and we also use it to secure, temporarily, some things to the table. The lamp is important too, as it directs the attention to specific points of the drawing.

Accompanying us, stuck to the walls, are drawings, old sketches, or photographs of the site. An architect’s desk is surrounded by their own imaginary, and these drawings are an extension of their ideas. Also, in some way, their books, models, and photos are fragments of their mind. When you sit down and start working, these elements are activated; the pieces of paper and set squares begin to move, and you get drawing.

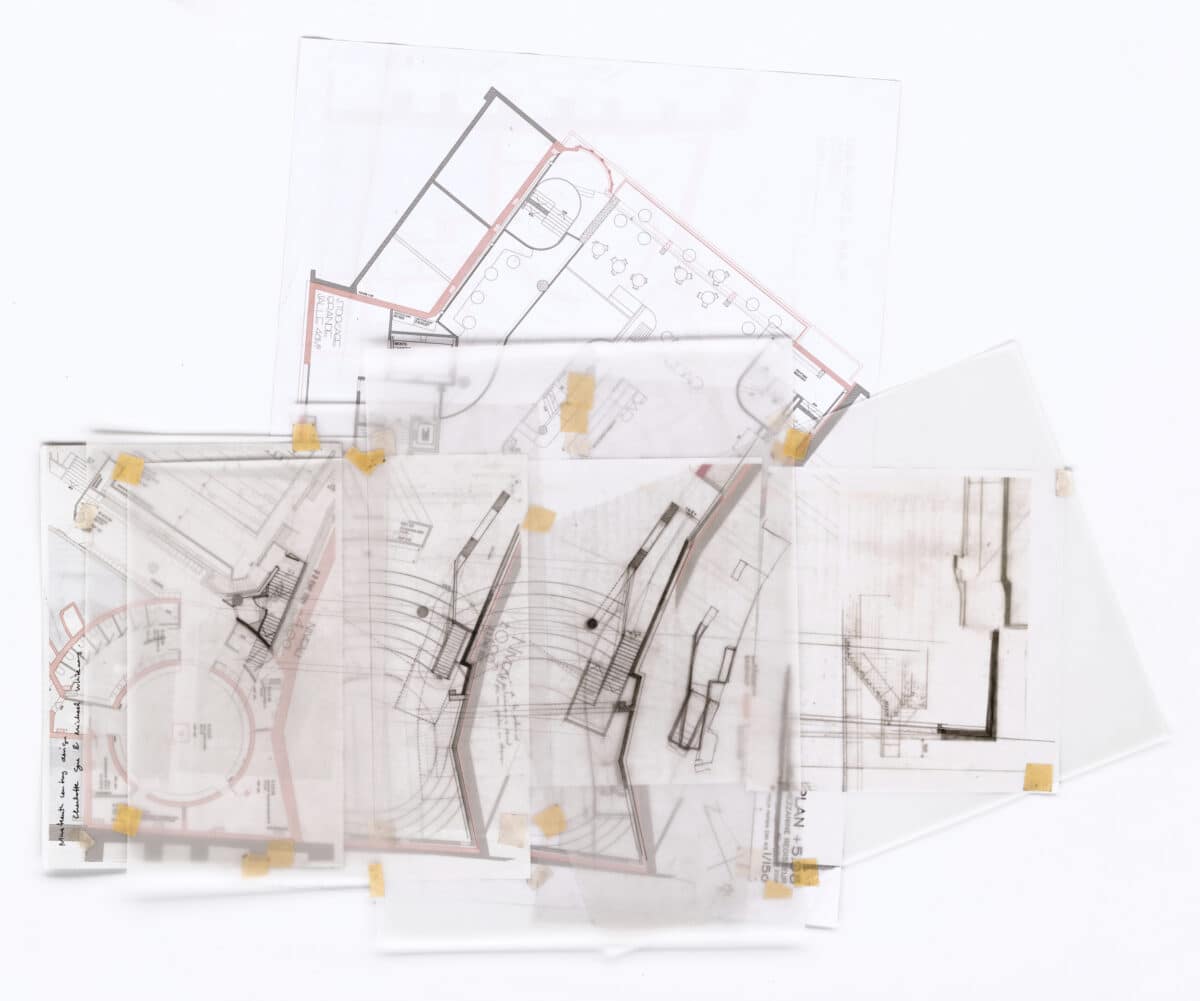

Overlapping Papers

There is another kind of document that records the process, in layers: one drawing is superimposed upon the previous one, and a complex document is thus created, an amalgamation of overlapping papers. We print out digital documents as a base to work upon, and then we lay a sheet of tracing paper on top and start drawing on it. The digital base gives a kind of certainty, a set structure to be developed and modified. However, when a sheet of tracing paper is placed on top of it, the image below fades somewhat, and cannot be seen so clearly: this method gives you the freedom to come up with new ideas, because it creates a certain distance. This is a good way to work because you reflect upon or critique the layer underneath, while also actively turning it into something new.

How do you construct a drawing that encompasses the multiple dimensions of a project? We normally start by printing and carefully laying out on the table all the drawings that relate to the particular area of the project that we want to work on, so we can bring together all the relevant information. This document is made from fragments of floor plans, stuck on top of each other, with one or more elevations. So this base is the starting point, and then we might draw, for example, a section to clarify how a certain part of the project works, at the same time that we study how each level might be affected by that section. You might need several floor plans of the project to build up the cross-section, so you order the different plans and align them on top. This is when the set square and parallel ruler come into their own: with them, you can project the plans onto the section below it. The section and the fragments of the floor plan inform each other, and you end up with a new drawing made up of complementary pieces. Left on the tracing paper is a fragment of the reality of this project; the rest gradually fades away.

In the drawing process, we put all our knowledge and ideas down on paper, everything we know. Therefore, by the end, these papers are documents that register exactly what we were thinking at that time. This document records everything, not only the drawing, but also numbers, texts, all of it. Whatever is in your head gets ‘thrown’ onto the paper, and then these documents become a container of the time, the conversations and concerns involved in the evolution of a project. They might be formed by many tiny fragments, each an attempt to understand the problem: a façade on the bottom, with a fragment of a floor plan on top, and then a section to the left because you need to know how it all works together… If you have all the information in front of you, you understand the whole problem. Then, you can modify the plan; for example, you might raise or add a step, and you can easily adjust all the drawings in line with this adjustment. You can control the whole thing.

When you draw the various dimensions of a problem all together, your eyes move from one drawing to the next, and you connect them in your mind. That’s when the space begins to feel real, and you can work on it. This is a relational way of thinking that relies on the direct connection between eye and hand: the drawing is the result of the impulse and intuition of these two together. Therefore, this approach is less effective if some parts of the drawing are on a different table or screen, because this disrupts the thought process and the solutions do not articulate the different parts of the project. Drawing by hand is a direct reflection of what we are thinking, so it is impossible to draw only in plan or only in section. That is, the hand moves as our head moves, and the drawing reflects the complexity of our thinking: we link together the multiple dimensions of the reality before us.

The Size of the Paper

These documents are made up of fragments of computer drawings under several layers of tracing paper, i.e. everything that we deem necessary for studying a certain part of the project. The document is so big that some of the paper might have to be tucked under the table to be able to keep drawing. It is large, but you do need it all; you must not limit your inquiries to the size of the paper. If you have big sheets of paper and big printouts, you can draw by moving right or left, in plan, and in section. You don’t know where your thoughts will take you, so you should give yourself the freedom to move around the paper, without having to hold back. If you only have an A3 sheet, the development of your thinking will be restricted, and that’s a shame.

The final document might end up having many layers of paper, because you had to do more and more tests. It’s great to build up a document brimming with your interests, one that starts to grow and incorporate other aspects: not only sections or floor plans, but there might also be a diagonal view of the space. If and when there is too much information, you can always put a blank piece of paper under the last sheet of tracing paper, only the part that you need to focus on, and hide what is further beneath; this way, you can concentrate on one part, and start rethinking the space. You then have a new part of the plan, a new reality that emerges from that day’s design work. Then you label it with the date, the scale and all the information that you think is important to register.

It’s interesting to see how this document can change over time: first comes the computer-drawn base, composed of several printouts folded and stuck together to form a precise amalgam of the fragment being studied; then there’s a big drawing by hand on tracing paper, which is just a selection of the computer drawing. Next comes a new version on top of it, with a new idea or new perspective on the problem, and so on. After each revision, the drawing becomes richer, but for even greater clarity we can slip blank pieces of paper in between and hide some older lines of thought. Thanks to the size of the paper, we can fit in more drawings and studies of the part of the project that we are dealing with at that moment. It becomes a complex document with many layers of paper, featuring multiple studies that contain all your reflections on the project. Even so, you might need to go back to this document at some point, because you’ve suddenly had a brainwave…

Ricardo Flores, alongside Eva Prats, runs the Barcelona-based office Flores & Prats.