Impressions of the Siza Exhibition

When I was an architecture exchange student at Faculdade de Arquitetura da Universidade do Porto (FAUP), between 2000 and 2001, there was a legend you could knock at Álvaro Siza Vieira’s office door and end up working there as an intern—the equivalent of walking into Mount Olympus to collaborate with Zeus. My admiration for Siza has since grown and faded but never receded enough for me to stop thinking of him as one of the greatest architects of the twentieth century, and an architect whose creations trigger a variety of emotions.

In August 2024, I visited the Siza exhibition at the Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation in Lisbon, after a technical visit to Casa da Arquitectura (Matosinhos) and on my way to Switzerland for a visiting professor period at the École Polytechnique Fédérale de Lausanne (EPFL) within the CAPESPRINT program of Universidade Federal da Bahia, my home institution. A couple of weeks later, I was visiting the Drawing Matter Collections (DM), having been invited as a lecturer for the workshop ‘Drawing Research Platform’ organised by Professors Patricia Guaita and Raffael Baur, based at ENAC/EPFL (ALICE lab). I had been researching through the DM Catalogue—being a guardian of part of Siza’s archives—drawings of Siza for my lectures, some of which were also present at the exhibition. These coincidences enhanced my experience of the exhibition, paving the context for the impressions I share here.

Curated by the Spanish architect, critic, and curator Carlos Quintáns Eiras—who also co-curated the Spanish Pavilion at the Venice Biennale in 2016—the exhibition aimed to cover all creative aspects of Siza’s career, relying upon archives deposited at the Serralves Foundation, the Canadian Centre for Architecture (CCA), the Drawing Matter, as well as the Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation and the architect’s studio. The exhibition was organised through thirty architectural concepts (such as ‘articulating’, ‘folding’, ‘fragmenting’, etc.), each comprising three built works that could exemplify or materialise these ideas—offering a broad yet detailed approach to Siza’s work around ninety buildings. The show welcomed the viewer with a great set of photographs, almost abstracts, followed by a handle-ready facsimile of Siza’s ‘legendary’ notebooks and some originals within glass cases. Three long lines of tables formed out of printed plates occupied the main exhibition hall, showing pictures, drawings and texts related to these selected works and their concepts, accompanied by a great set of original drawings hanging on the adjacent walls. Pieces of furniture, designed by Siza, and a video installation completed this first part. The show extended into a second room at the lower level, beautifully exhibiting other hand drawings by Siza, including drawings on papers glued to cigarette boxes—that Siza covers to avoid seeing the scary health advice, I suppose. The quality of the curatorial work was outstanding, and very accurate. Both the thirty concepts used to organise the information, as well as the selected works, were thoughtful. The physical arrangement of the exhibition was also carefully crafted, paying beautiful homage to Siza’s aesthetics. It allowed the viewer to go through everything in a very pedagogical way, achieving the complex goal of synthesising the huge amount of material available.

However, I did miss two elements. The first was a closer interpretation and analysis of Siza as a builder, and his architecture as a built element. It felt important that this could have been addressed in a critical way, while also exploring the idea of drawing in architecture as a means to its production and not something with an end in itself. There are building artifices used by Siza to achieve the effects and spaces he designs that would be interesting to investigate, showing the relation between these and construction details and material decisions. Some exhibition galleries in museums Siza designed, such as the Iberê Camargo Foundation (Porto Alegre, Brazil) or the Serralves Foundation (Oporto, Portugal), for example, are the result of creative roof and ceiling designs that allow for natural light to enter, although the way these are built is not always obvious. Other aspects, such as the tectonic and stereotomic language of designs employing stone, could also be appealing, acknowledging historical references and the role of the Portuguese stone masonry (and masons) in the development of this material aspect of his work. I would, therefore, add a thirty-first concept along with those of ‘pleating’ or ‘tapering’: ‘building’. In this direction, the idea of relating the drawings and real furniture within the exhibition was a clever one, helping to fill what felt to me as a gap.

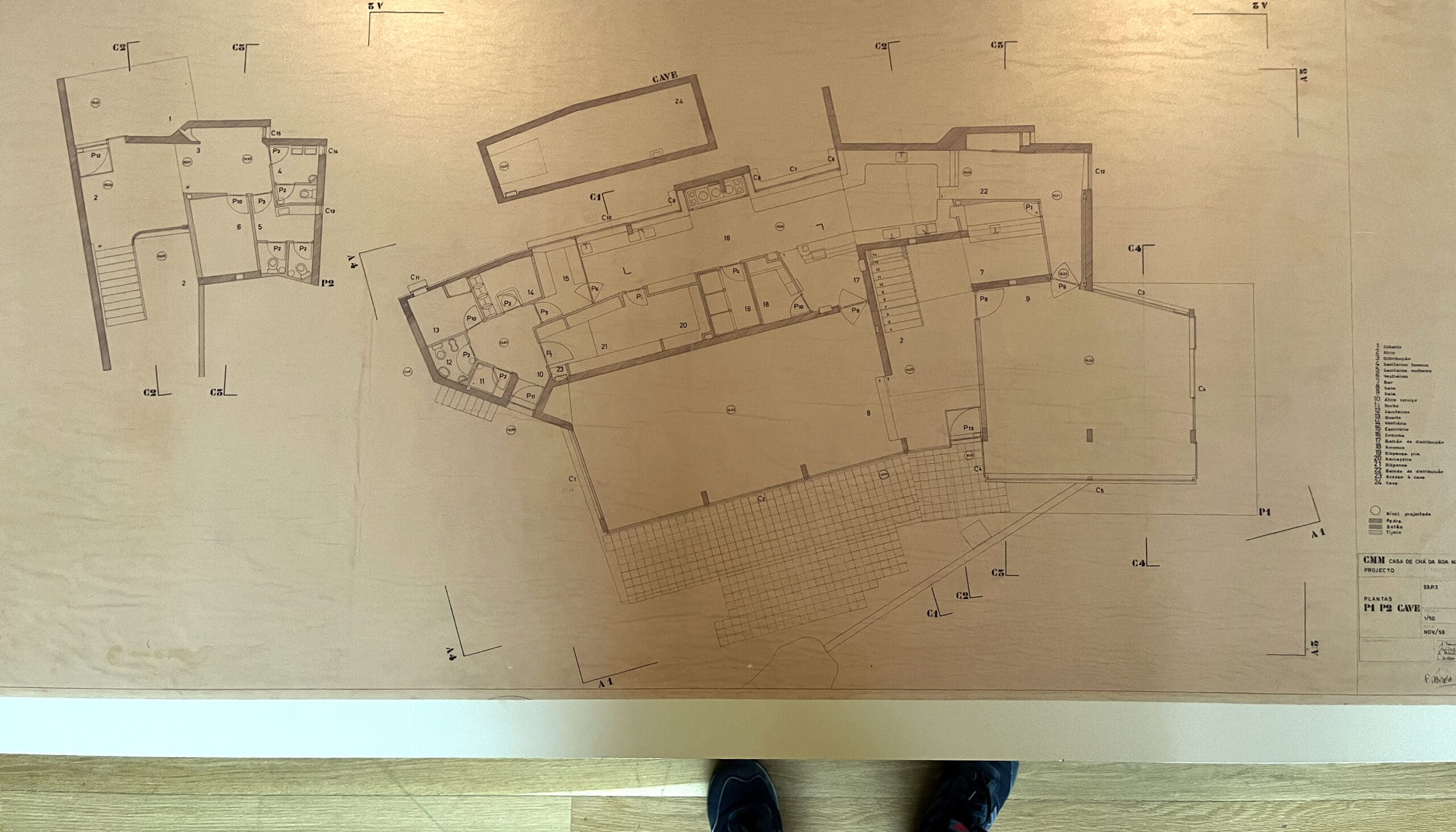

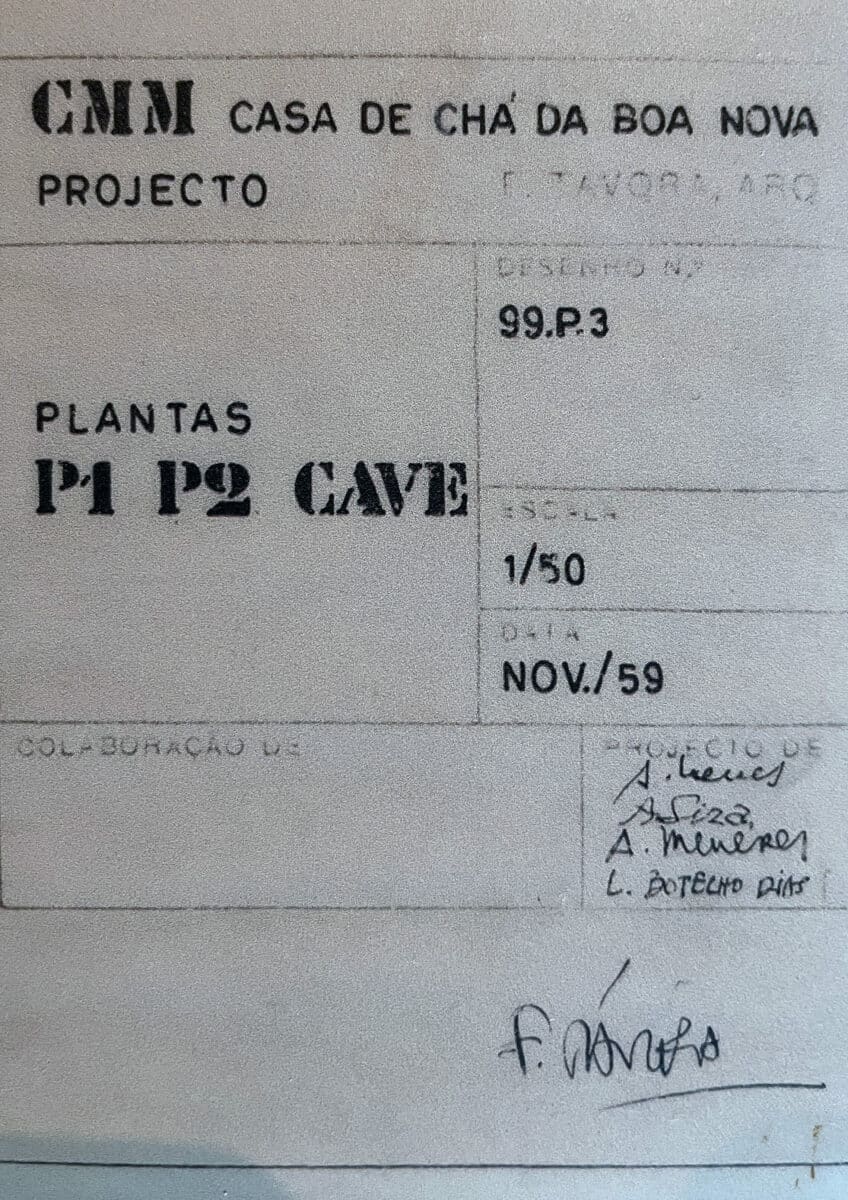

Secondly, I missed the reflection on the transdisciplinary and collaborative work between Siza and other architects, engineers, construction workers and clients that effectively led to that amount of work—this may have deserved some light, especially in times in which a more collective feeling within the production of architecture is expected of our society, in contrast to the lonely star-architect paradigm. In Siza’s case, this is illustrated, for example, by the Boa Nova Tea House building, a project led by him but in collaboration with other architects—namely Alberto Neves, António Menéres, Botelho Dias e Joaquim Sampaio—usually not regarded as co-authors. The building is actually the result of a competition that architect Fernando Távora handed over to his team with some defined outlines before leaving for America as a Gulbenkian fellow.[1]

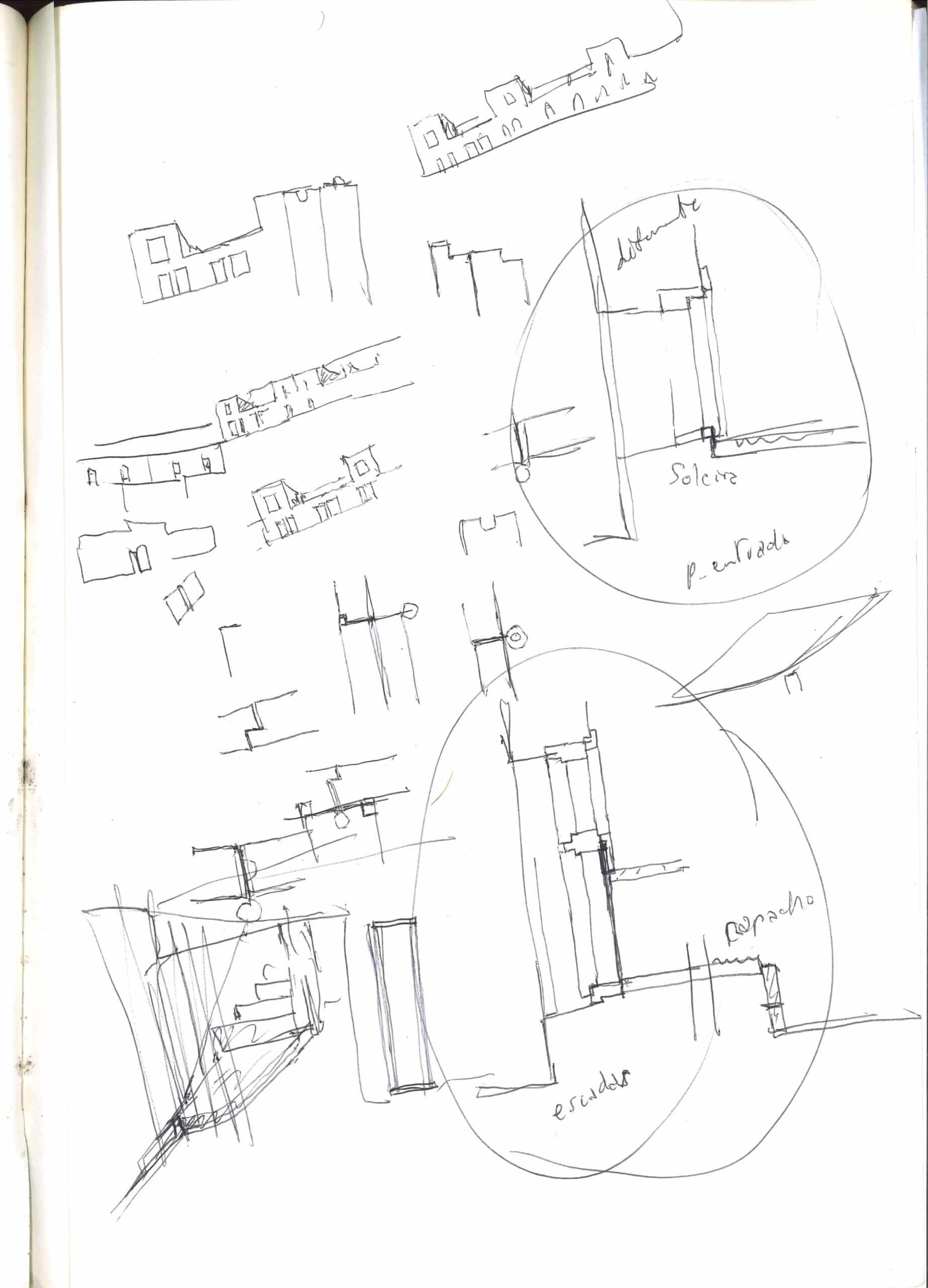

In that sense, it was joyful to see Siza’s sketchbooks and other freehand drawings, such as the travel sketches and portraits, both in the second part of the exhibition and at DM archives two weeks later—in the latter, the originals A4 sketchbooks for Évora. They granted access to a privileged window into the ‘Olympic’ office over the Douro, allowing for an unusual view of his process, architectural development and thinking. It was interesting to compare drawings made by the architect, and other drawings which are the product of studio work and collaborations, and it was different from seeing these reproduced in books. It allowed for the perception of a more ‘human’ working process, while revealing the uncertainties, speculations, decisions and design development embedded in the design process. In the end, it made me fonder of Siza’s work—if that is possible—and also more conscious of the amount of collaboration required to materialise his ideas in the real world, and out of paper.

With many thanks to Fundação Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior (CAPES); Universidade Federal da Bahia (UFBA) – Programa CAPESPRINT; ENAC Summer Workshop Drawing Research Platform Somerset (Prof. Patricia Guaita and Raffael Baur); and Drawing Matter Archives (Niall Hobhouse, Jesper Authen and Matt Page).

Notes

- See, for example, the article: Ricardo Meri de la Maza, Clara E. Mejía Vallejo, ‘Naturalezas appropriadas en las primeras obras de Távora, Siza y Souto de Moura’ (Appropriate Nature in the early works of Távora, Siza and Souto de Moura), ZARCH 17 (December 2021), 108–121.

Sergio Kopinski Ekerman is an architect, urban planner, and Associate Professor at the Faculty of Architecture of Universidade Federal da Bahia in Salvador (Brazil) where he was the Dean from 2020 to 2024.