In the Archive: Abattoirs, Boucheries, and Slaughterhouses

Click on drawings to move and enlarge.

As architectural typologies, abattoirs, boucheries, and slaughterhouses embody the civilising of animal slaughter; serving as concrete expressions of the culture of animal consumption. Over time, the slaughterhouse has evolved in both its structures and perceptions, from a small-scale, craft-based operation rooted in necessity, to large, mechanised sites of mass production—‘the disassembly line’ as Sigfried Giedion puts it.[1] The dissection, violence, and suffering inherent in these sites are often rendered invisible, obscured by architectures that emphasise civic importance, technological advancements, and environmental controls. The Drawing Matter collection holds a few drawings related to this civilisation of the meat industry’s infrastructure.

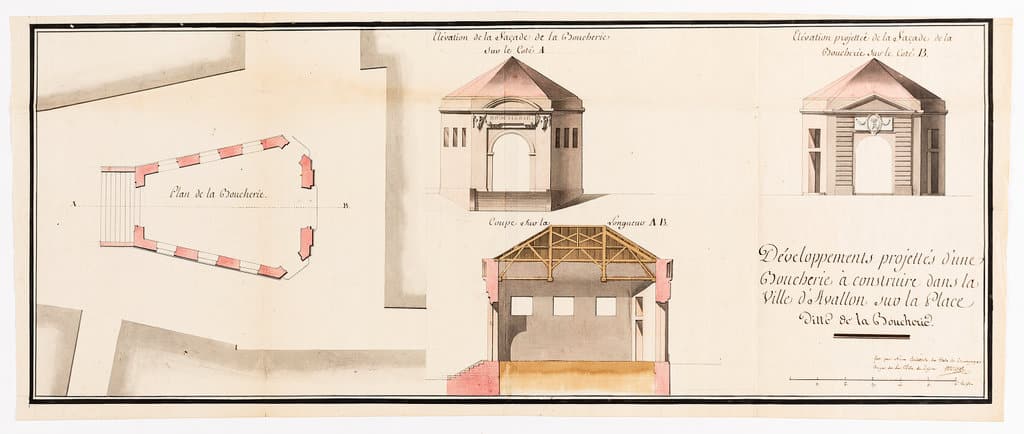

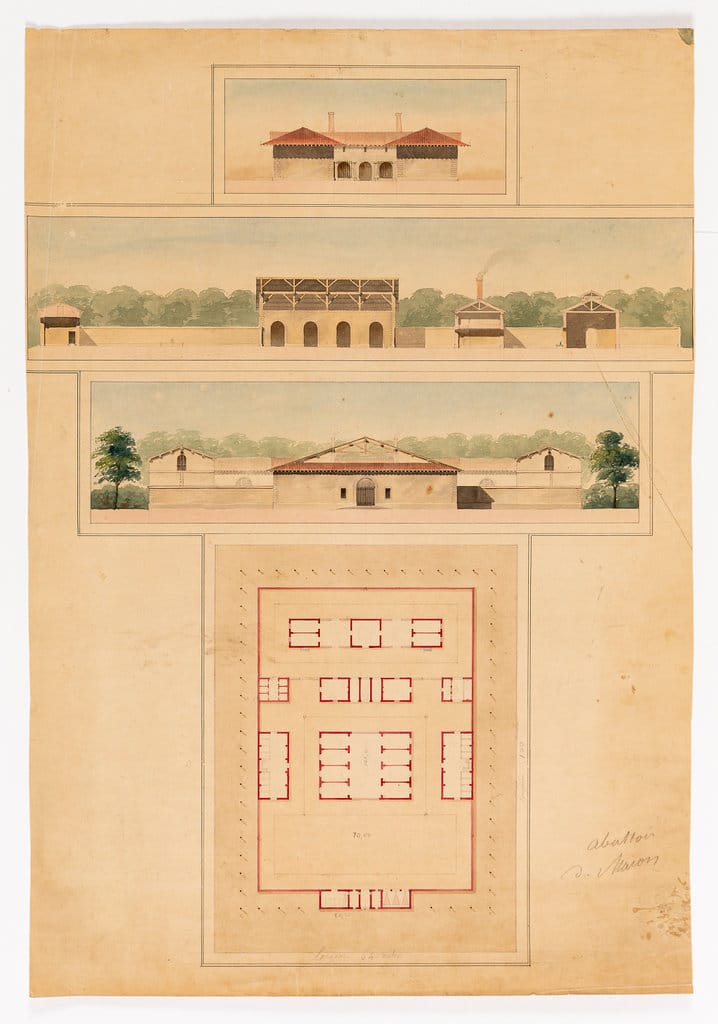

Charles Joseph Le Jolivet designs a hygienic, open structure for a boucherie in Dijon, emphasising lightness and ventilation. Large windows and doorways punctuate the walls, while the pitched roof’s wooden structure contributes to the space’s generous height. The elevations continue this simplicity, the first rendered in the Tuscan order, adorned only with two bucrania and the plain inscription, ‘Boucherie’; the second in heavily rusticated stonework, topped with a swagged roundel. In its austere ornament and lowly order, the market is described as a service structure with little social value, a space of sacrifice and selling. Similarly to Le Jolivet’s proposal, Paul Piot’s design for an abattoir and boucherie in Mâcon, France, rationalises the typology of the structures. In his series of drawings, we are offered an efficient and economical concept, with the programme of the site defined in its control of space and composition. At its centre are eight échaudoirs for the slaughter of cows, sheep, and pigs, then sixteen bouveries for the holding of live animals, but the processing space is separated, seen at the top of the plan in three closed structures. Le Jolivet and Piot’s designs reflect Enlightenment ideals, blending morality, social welfare, and environmental control in their formation of typologies. Their buildings echo both Roman architectural dignitas and contemporary advancements in hygiene and public health.

Similarly, James Bunstone Bunning’s proposal for the ‘improvements’ to Smithfield Market in London reflects the site’s evolving social significance. The drawing’s caption underplays the changes Bunning is making; he not only expands the scale of the market but moves its location entirely, repositioning it alongside Cow Cross Street and extending it toward Charterhouse Lane. In Bunning’s title of the proposal as a ‘neighbourhood’, it is clear that he envisions the market as a distinct district of the city. But he nods to its smaller original site in front of St Bartholomew’s Hospital, now marked with a circular structure with a central tower. With the city’s preparation for the 1851 Great Exhibition, which produced a wealth of civic projects, Smithfield would represent Britain on a global stage; even London’s infrastructure was invested in representing British values, vision, and technology. The market therefore extends from a monumental red-brick facade, bustling with traders and clients, and in the project plans it stipulates vitrified bricks for hygienic cleaning, iron columns that double as drain pipes, and a ‘kick bar’ in all livestock pens.[2] But despite its grand new scale and hygienic technologies, the market’s pens are devoid of animals; the rational grid is ready to be filled.

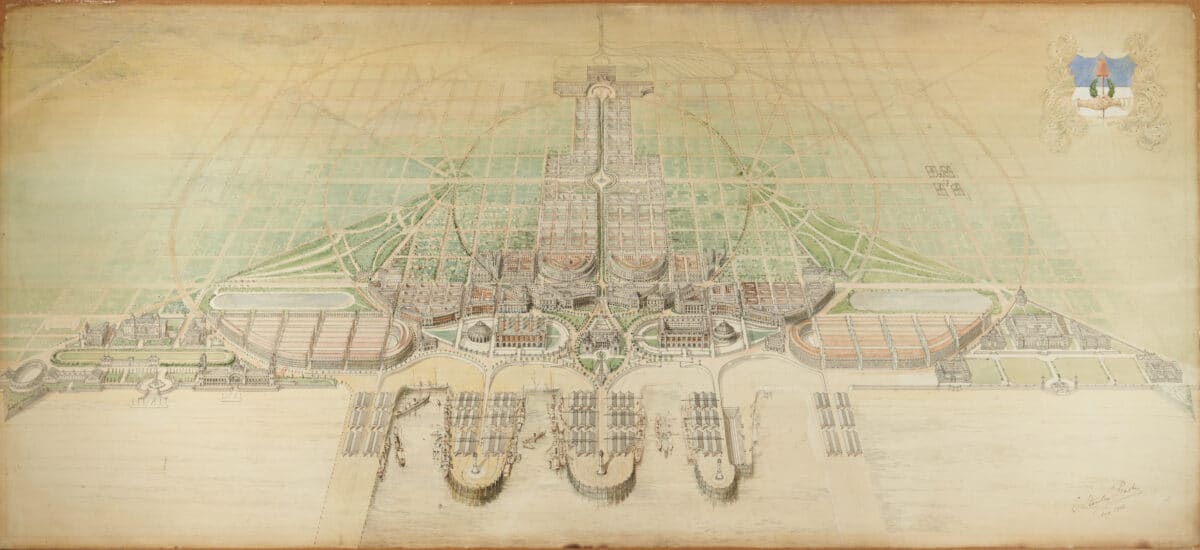

Charles Stanley Peach’s green and gold drawing dominates the virtual plan chest above, a vast horizontal image of a proposed city in the Bay of Samborombón, along the coast from Buenos Aires in Argentina. It often dazzles visitors to Drawing Matter, drawn to the concentric and gridded pattern of the glittering metropolis. This fascination only grows by telling them of its purpose: a slaughterhouse city. Held within the harmony of the city plan, located on the seafront are two large slaughterhouses, covered shelters close to the harbour, with boats at the ready to export the product. Both in the anonymity of the slaughterhouse typology and the emptiness of the green land beyond, we are presented with the slaughterhouse city as a consequence-free site: an expansive and fertile land that will support the city with an endless stream of willing livestock.[3]

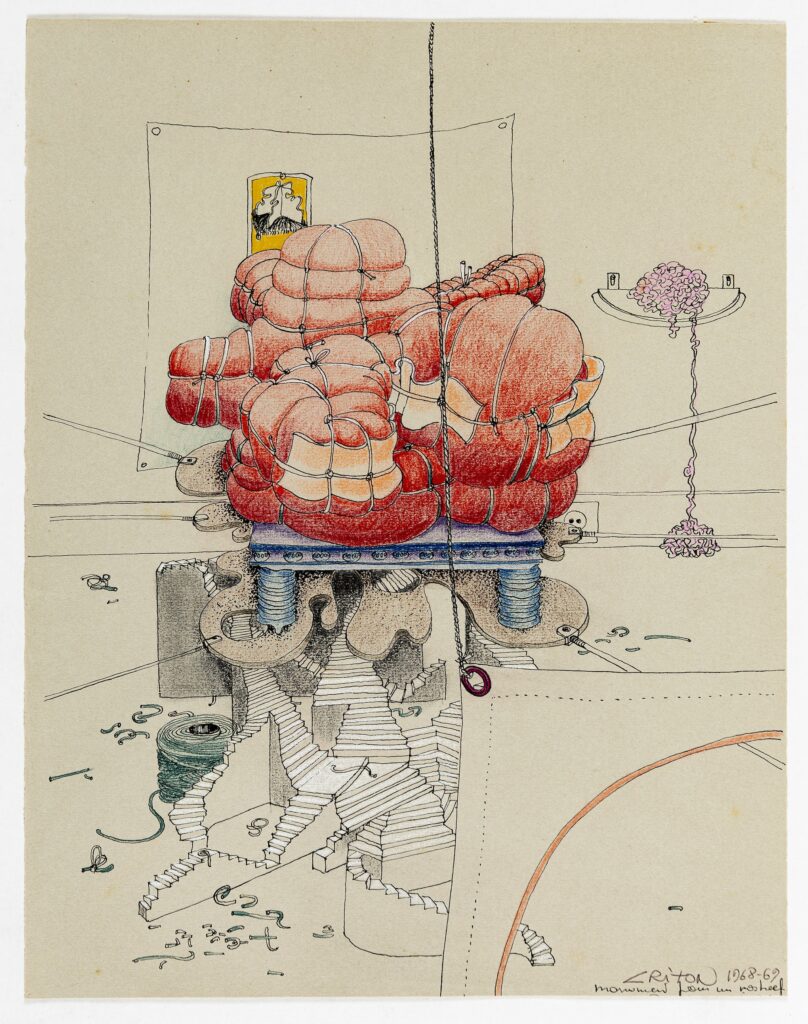

Jean Criton’s ‘Monument pour un Rosbeef’ offers a visceral contrast, its pulsating, iron-rich forms expand to fill the subterranean space of the ‘Forum des Halles’. In the late 60s and early 70s, Victor Baltard’s monumental glass and iron structures of Les Halles Market underwent a large-scale renewal to make way for a modern underground shopping centre. In Criton’s vision, the Pavillon de la Boucherie, which had been controversially demolished, is fighting back: the raw mass of meat dominates the space, unshackling itself from the butcher’s twine.

Notes

- Siegfried Gideon, Mechanisation takes Command (New York, Oxford University Press, 1970), 231.

- ‘On the Market: Victorian London’s finest cattle market’, Lyndon Goode Architects <https://www.lyndongoode.com/on-the-market.html> [accessed 07.01.2025]

- Paula Lee, Meat, Modernity and the Rise of the Slaughterhouse (Hanover, London, University Press of New England, 2008), 6.