Notes on Nabokov

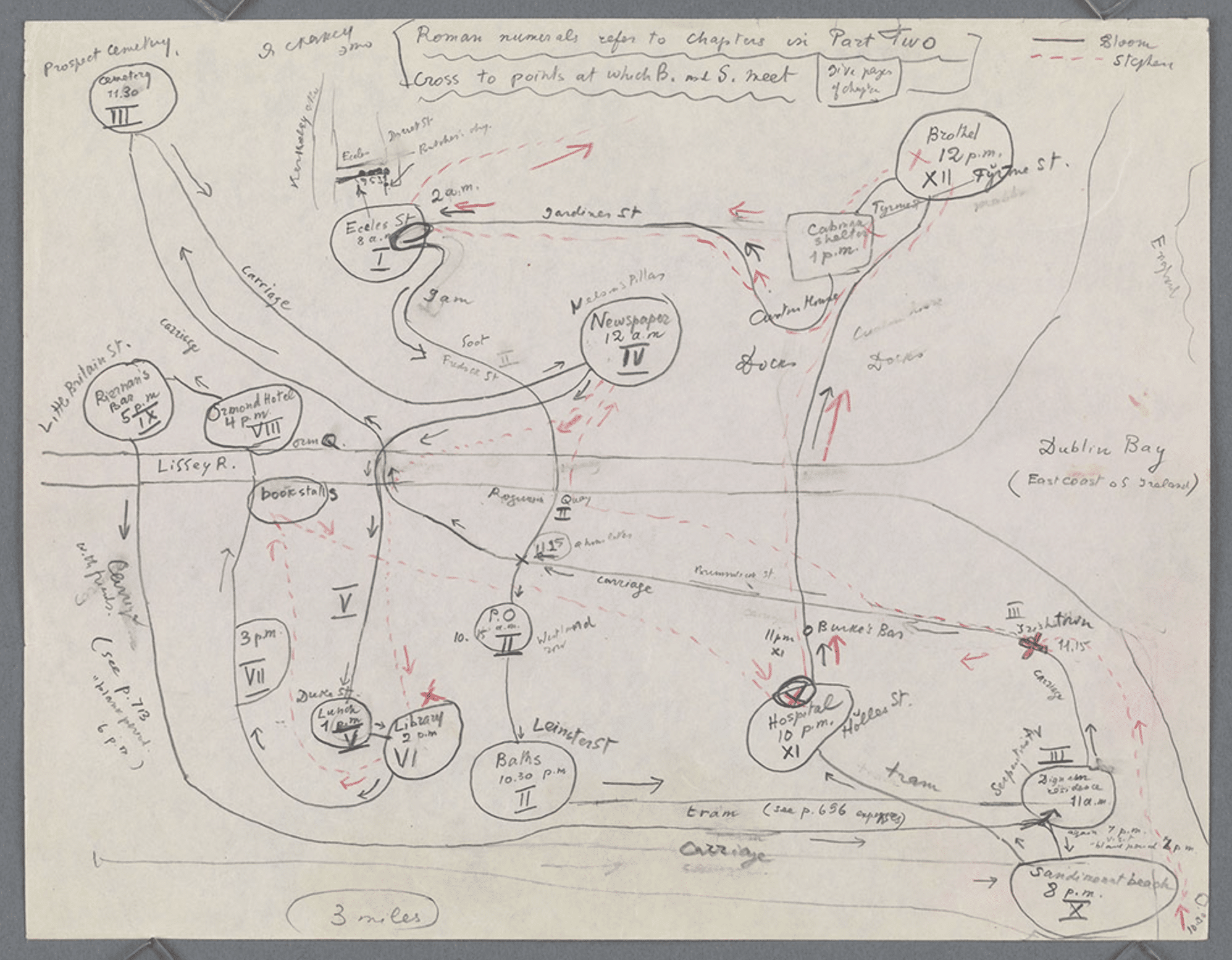

Between 1948 and 1958, Russian exile Vladimir Nabokov (a heavy open ‘o’ as in ‘knickerbocker’) taught a course at Cornell University called ‘Masters of European Fiction’. This drawing—one of a few that Nabokov would make as part of the course—depicts a map of James Joyce’s Dublin in Ulysses. Drawn are the intertwining itineraries of central characters Leopold Bloom and Stephen Dedalus of the middle twelve sections of the book. A key in the top rightmost corner of the page indicates Bloom’s path as a steady black line and Dedalus’ dashed in red. Within the drawing are other references to scale, geographical location and time. The two parallels which bisect the drawing are labelled as the Liffey River washing out to Dublin Bay on the right-hand side of the page (England is shown scrawled as a wayward scribble further right of the bay). Across the bottom of the page runs a faint line indicating a scale of three miles within which the episodes take place. Roman numerals and page numbers refer to the text itself, whilst place names fill bubbled islands of activity. Bloom’s and Dedalus’ paths, with accompanying modes of transportation, wind and squeeze their way between them. Arrows indicate their direction of travel as the day progresses. One can read the drawing by tracing either Bloom’s day, beginning in the centre left island at his home on Eccles Street as his line coils its way around Dublin finishing where he began. Or, perhaps by coming in from the bottom right corner as Dedalus, whose light red lines dance faintly around Bloom’s, sometimes blowing close enough to meet (these are marked with crosses) and other times tragically asynchronous, out of space or time with one another. Like the novel itself, the drawing appears to make parallels with Homer’s The Odyssey. Chapters and places are depicted as distinct islands amidst the city of Dublin, resembling a kind of naval chart amidst the archipelago of classical antiquity.

The drawing Map of Leopold Bloom’s and Stephen Dedalus’s travels through Dublin is one example of Nabokov’s responses to the literature he was teaching—others include drawings of Jane Austen’s Mansfield Park estate and diagrams of Franz Kafka’s cockroach in The Metamorphosis (describing the parts of the insect anatomically, slyly noting that Gregor Samsa is a beetle and need only open his wings and fly away). Nabokov, who, in exams, was fond of asking students to recall the exact colour of the wallpaper in Anna Karenina’s room, felt that ‘literature consists of such trifles’ and encouraged his students to ‘fondle the details’.[1] Rejecting all interpretations—Freudian (‘the Viennese Quack’), Homeric, historical or otherwise—he instead favoured style and the exactness of detail in the text.

Much has been made of Nabokov’s polemic position on literature but perhaps less about the drawings that accompanied his pedagogy. Nabokov’s drawings are, in a sense, architectural reconstructions of literature. They are used not merely to explore the sensual and topographic qualities of the text but show how drawing relates to meaning and presence. Literary theorist Hans Ulrich Gumbrecht separates aesthetic effects into meaning—prevailing mostly in verbal arts as symbolic or semantic content—and presence—a spatial effect primarily found in visual arts and music that conjures corporeal sensations.[2] Following Gumbrecht’s theorisation, the drawings begin to explicate the sense experience of an artefact which is otherwise obscured through our symbolic relation to it. Nabokov caustically satirises the tendency to read through abstract allusions in his novel Pale Fire where Charles Kinbote obsessively uncovers himself and his own history in the lines of the titular poem. It is through the specificity of the drawing that Nabokov is able to unearth the private sense effects of a piece of work: traversing feelings that are more personal than bumbling broad discussions within ‘isms’ and frameworks. The practice of drawing is the triumph of presence, uncovering a richer interior experience.

Although architectural drawings, particularly of the technical variety, value precision and specificity, these precisions are measures (lengths and areas, cutting lists and contracts). The precision of the technical drawing does not (always) reach for the presence of the architecture but merely produces a bill of quantities. To evoke a work’s ‘beautiful burning life’, the drawing must be precise in another way, precise in the way a drawing by Joan Miro is—a passionate precision where ‘everything is in correspondence.’[3]

Notes

- Vladimir Nabokov, Lectures on Literature (Boston: Mariner Books, 2002), 1.

- Hans Ulrich Gumbrecht, Production of Presence: What Meaning Cannot Convey (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2004), 98-100.

- Nabokov, Lectures on Literature, 283.

Michael Becker studied architecture at the University of Edinburgh. His work was awarded the Sergeant Award for Excellence in Drawing and a commendation for the RIBA Bronze Medal. He likes drawing and is looking to get stuck in.

This text is one of the selected responses to the Open Call: Storytellers, Observed—an inquiry into the origin and circumstances of a single drawing (or series of drawings), observing the ways by which each achieves the specific purpose for which it was made. For further information click here.