Notes on Port Royal, Jamaica

– Paul Cox

My parents Oliver and Jean Cox were devoted ‘Jamaicophiles’, having worked on many projects in the country since the 1960s. One of the most enduring and absorbing was a proposed redevelopment of Port Royal as a renewal and upgrade of the historic city, rebuilding and restoring while making an interesting site for tourists and an enhanced economy for the local people. The project involved a lot of historical research and many drawings to understanding the layout of the city before and after its demise by earthquake and fire in 1692.

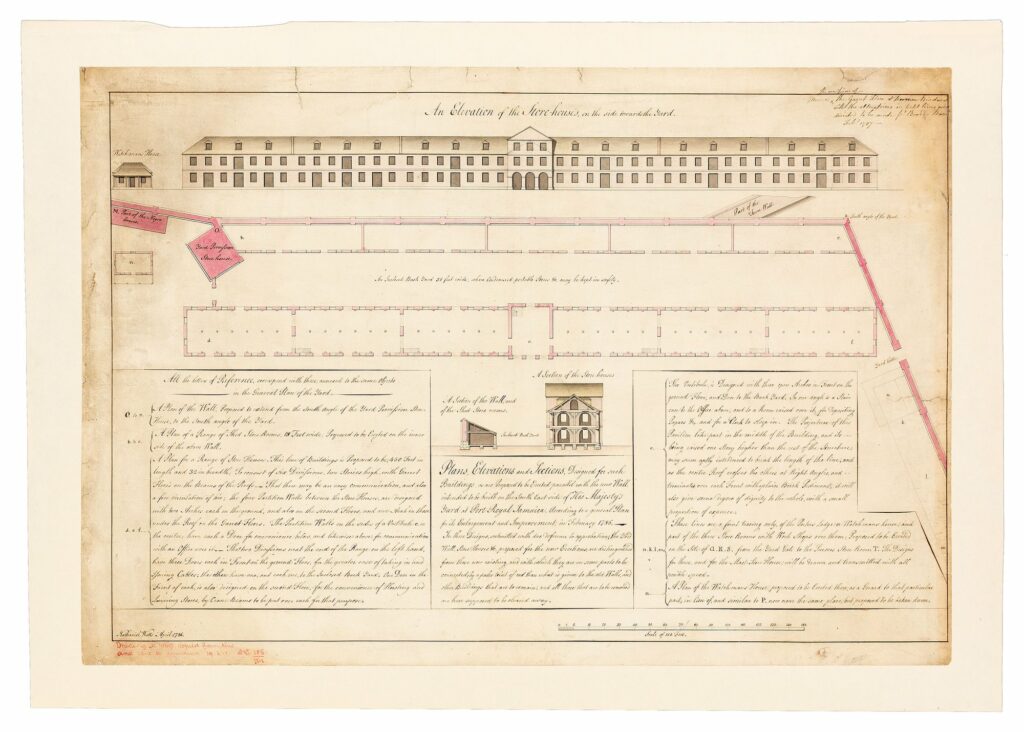

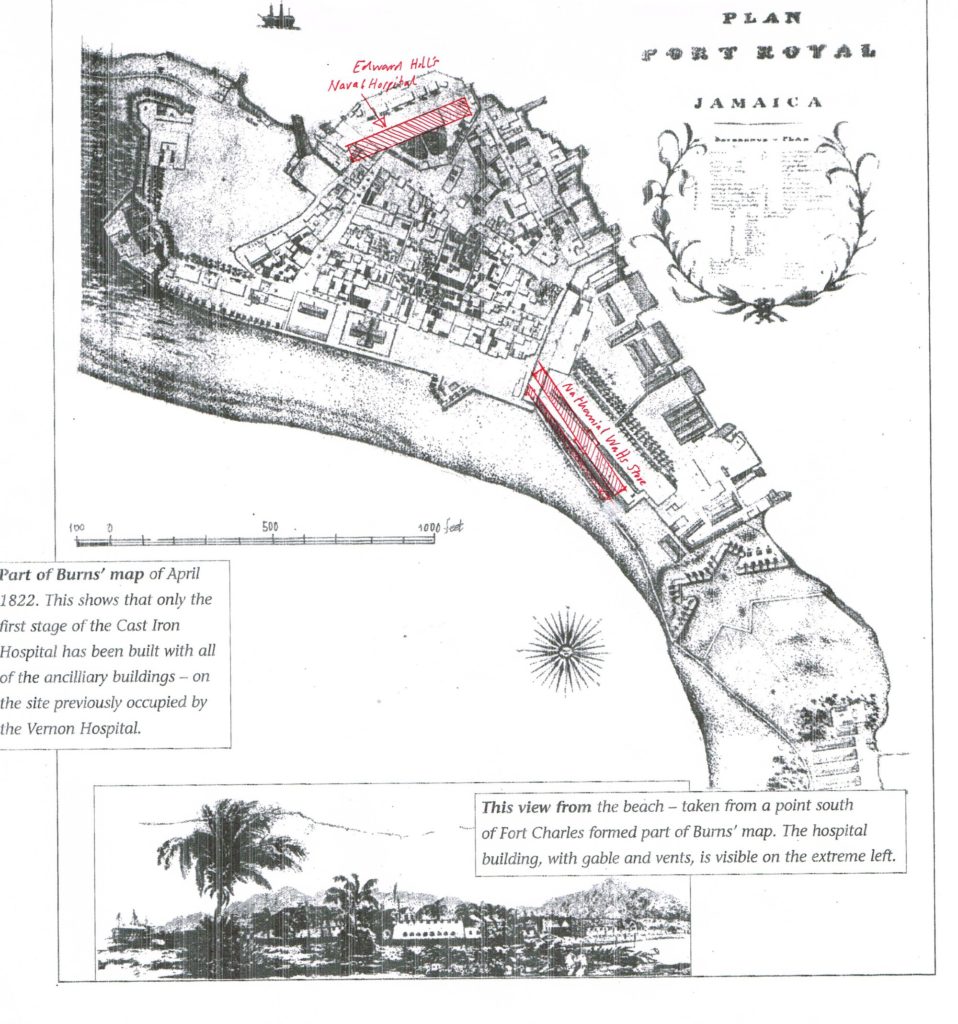

After the earthquake Port Royal remained essentially a naval garrison as an outpost at the end of the Palisadoes peninsula. The port defended the bay of Kingston and served as a strategic base for the protecting British interests in the Caribbean. The Nathaniel Watts drawing is intriguing as it was made at the time of similar investment in infrastructure in Port Royal by the Navy.

I have looked at my father’s notes on historic maps of the city of this period and there is no sign of any substantial building like the Nathaniel Watts storehouse. I am sure he would have been very interested to see this drawing as it would have represented the preferred design approach of the Navy Board at the time – incidentally all the brick, stone and iron used in these buildings would all be imported from England as ballast so the trading ships laden with sugar were not returning to Jamaica empty.

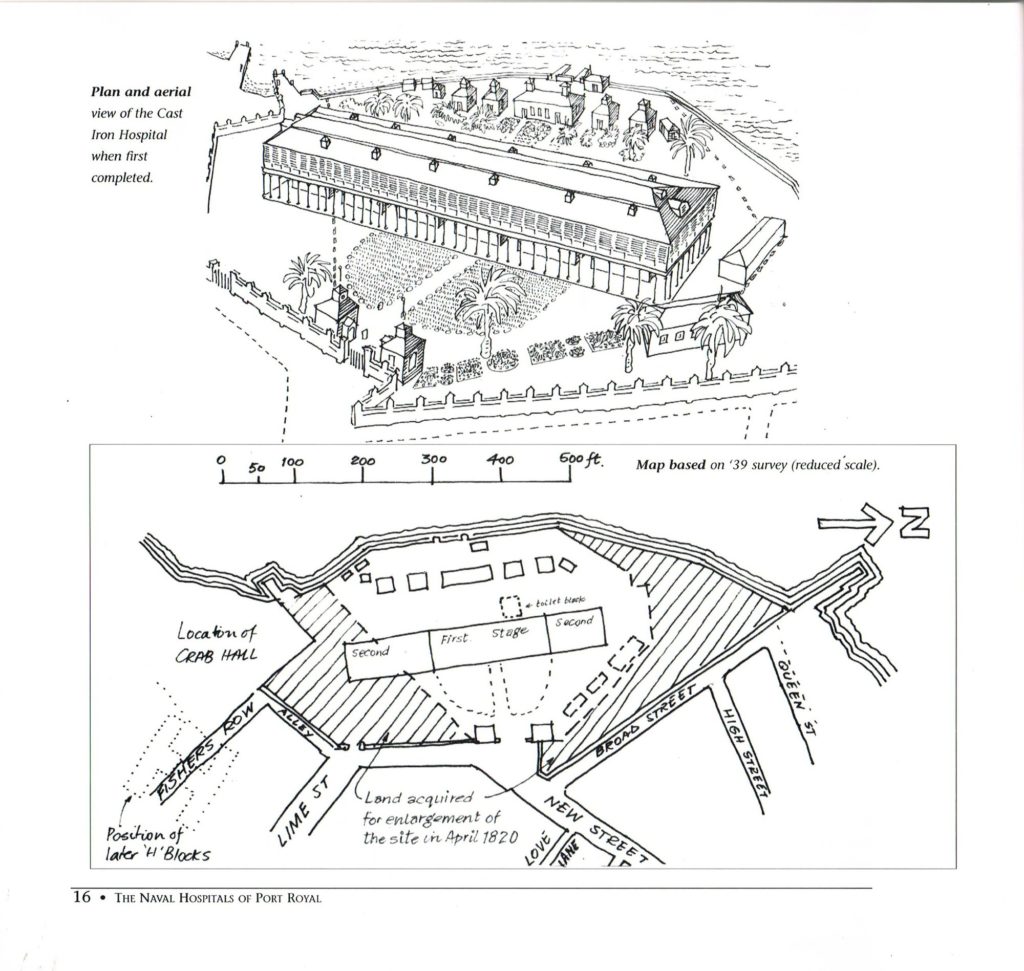

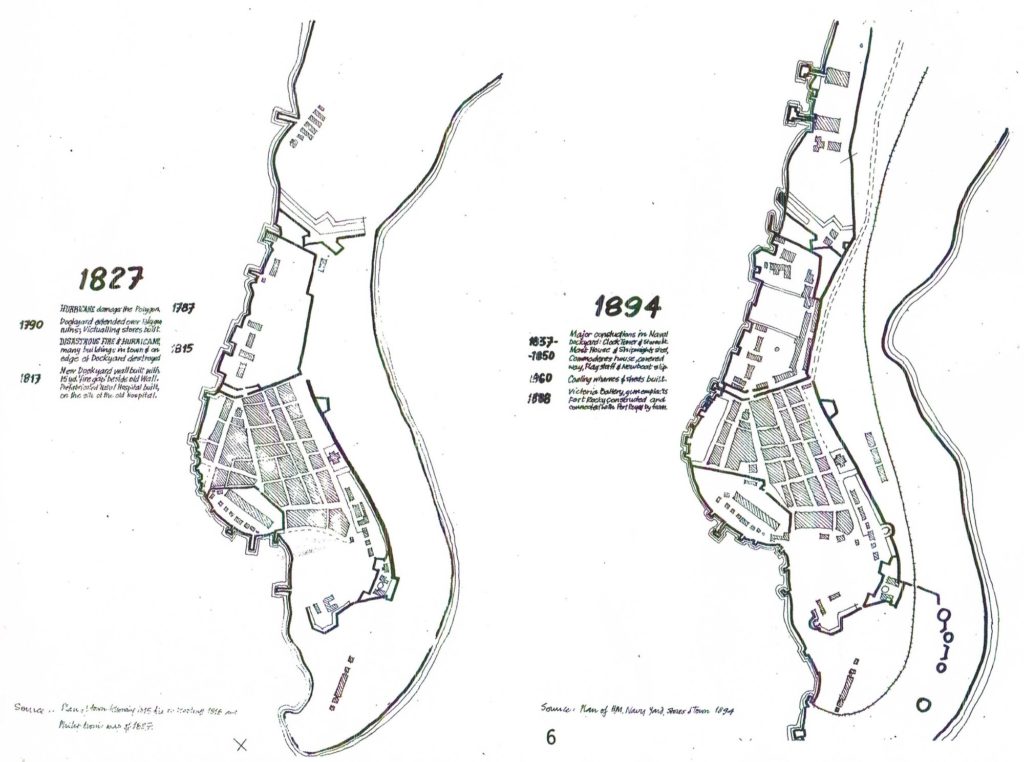

It is interesting also to compare this proposed scheme with the Port Royal Naval Hospital, the only structure to be built at a similar time and of a substantial size that survives to this day. I have looked at the report my parents did on the history of this building and a previous brick built structure that was destroyed in the earthquake of 1771. There is a note in their report of a victualling store being subsequently built in 1790 as part of the extension of the dockyard, but nothing on the 1827 map of any building of this imposing size abutting part of the town wall on the south-east side of the dockyard.

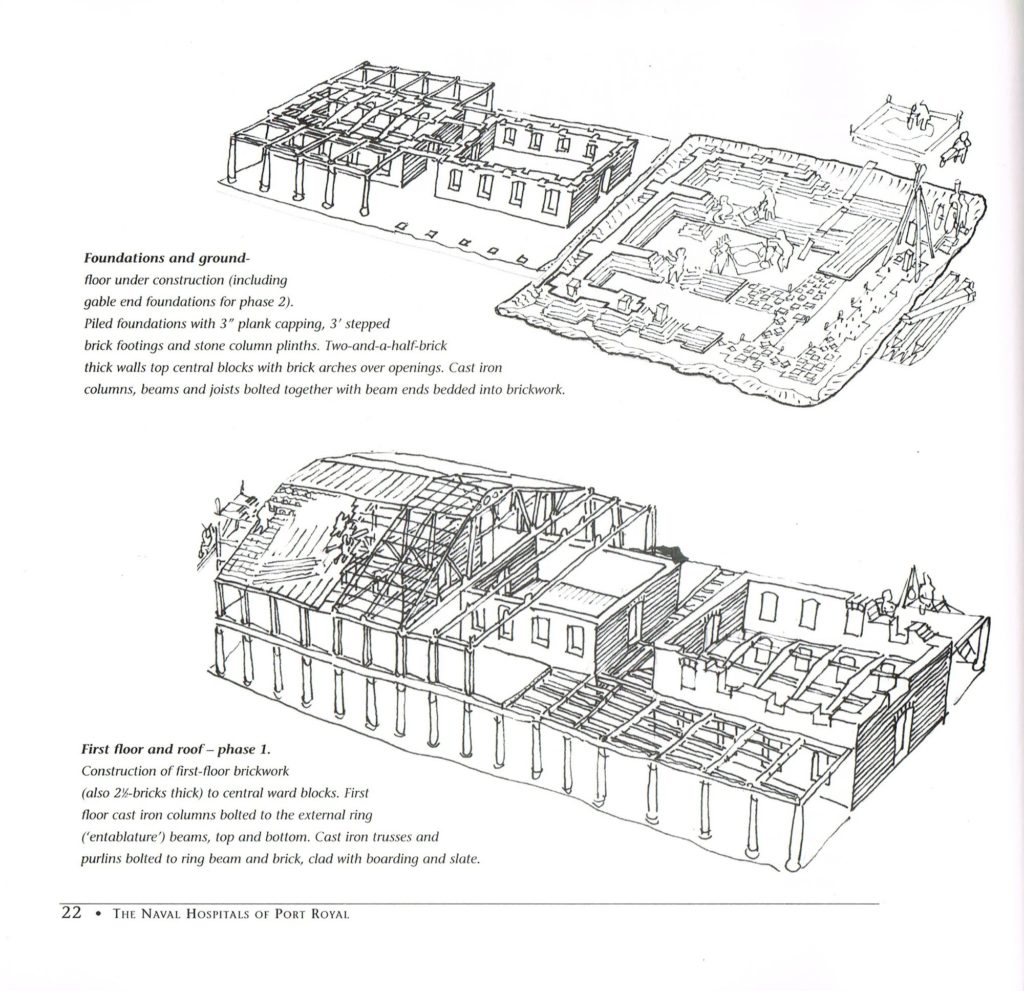

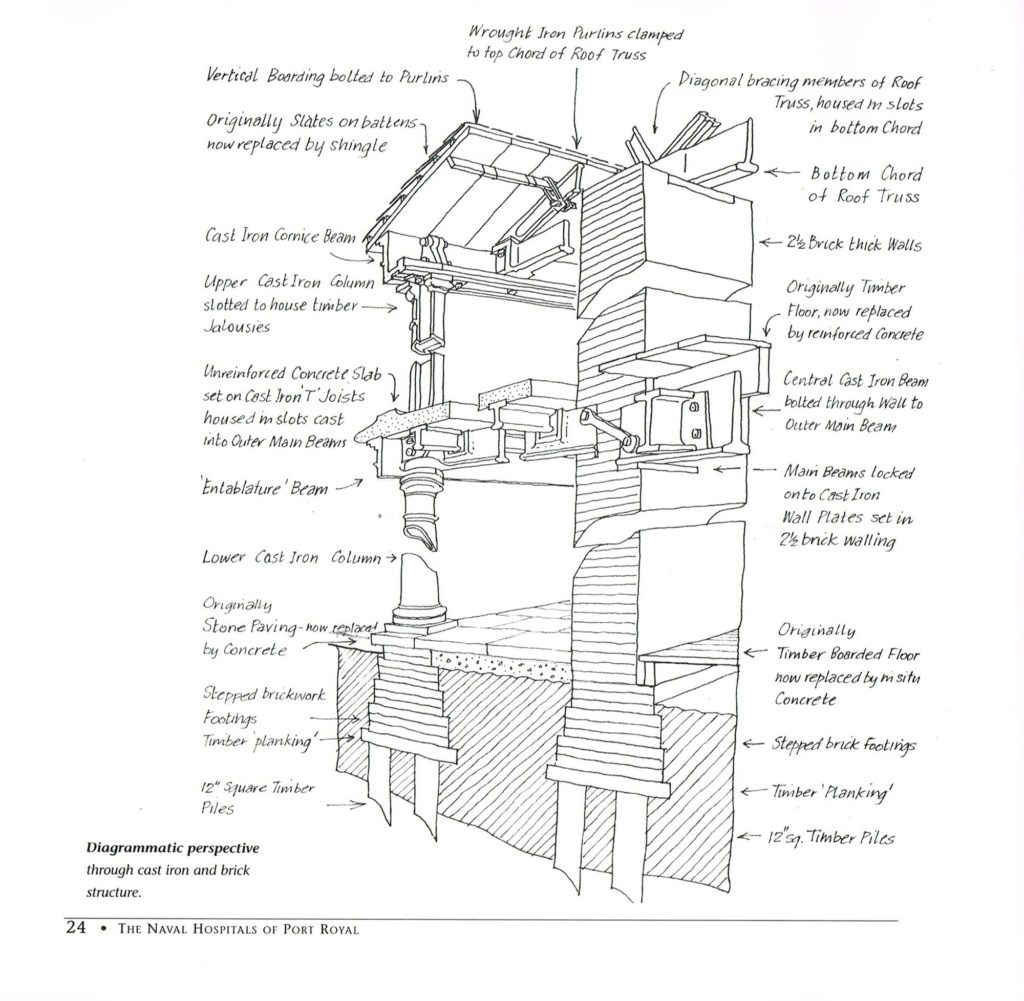

Reading my parents report on the hospital, it is interesting to note that the Navy officers commissioning and designing these buildings had ‘a lofty disdain for local conditions’. The navy, having failed with their first brick built hospital, commissioned professional architect Edward Holl to design its replacement in 1804. Aware of the tropical implications, the innovative Holl devised a cast iron superstructure built around six brick core elements. The ironwork was cast at the famous Bowling ironworks in Bradford to an ingenious interlocking design of Doric columns supporting a peripheral deck. This was surrounded by a curtain of jalousies that provided shade and controlled ventilation throughout the building (enhanced by being set tangential to the prevailing wind). The flexibility of this remarkable structure has enabled it to stand to this day intact after six major earthquakes and the same number of severe hurricanes!

The history and significance of the Naval Hospital – in terms of how it presented a new and more enlightened approach to colonial architecture – seems to be more relevant than the Watts storehouse. The ‘stoic’ references made in Watts drawing intend an imposing grand edifice, having some disregard for the vicissitudes and volatile location it was intended to be placed in. Using the stylistic context, the notorious Rose Hall, a planter’s ‘Great House’ on the north coast near Montego Bay with its portico and arched openings bears some resemblance. The treatment of the slaves on this plantation was renowned for its brutality. Sadly the story of the British exploitation of slave labour has a long and ever present legacy in Jamaica, you can be reminded of this by many of the surviving buildings around the country.

My parents’ work in Jamaica was always sympathetic to local needs rather than imposing a European objective to the schemes they were involved in.

From an email to the editors, 26 June 2020

Addendum: email to the editors, 2 July 2020

I have looked into the drawings in a little more detail and identified the location of the where the Watts storehouse would have been aligned to the south-east corner of the naval dockyard. You can see from the 1827 map there is nothing on that site though some buildings similar to the Watts arrangement appear on the 1894 map. According to my father’s chronology, Port Royal naval stores were built in 1838 and in almost the same position but somewhat smaller than to Watts’ design. In 1905 the naval dockyard was closed by Admiral Sir John Fisher Commodore as the navy withdrew from Port Royal and most buildings were removed. There was a major earthquake the following year; had the Watts building gone up it was mercifully spared from hurricanes and earthquakes during its existence if it had ever been there at all.

There was some allowance in Watts design to get benefit from cross-ventilation as the garret floor was open to allow for ‘free circulation of air’ through the open dormers in the roof. It would not have worked quite as adequately as the hospital’s ventilation system, as the building ran aligned with the prevailing wind and not tangential to it.