Gordon Matta-Clark

The Genesis of Architecture (and the Genetics of an Anarchitect)

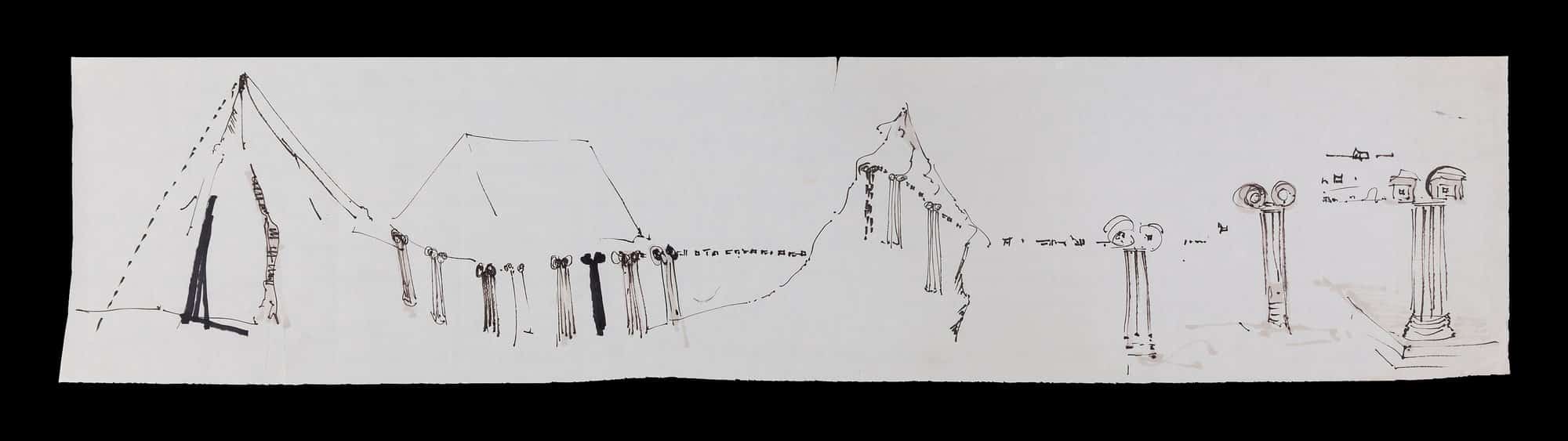

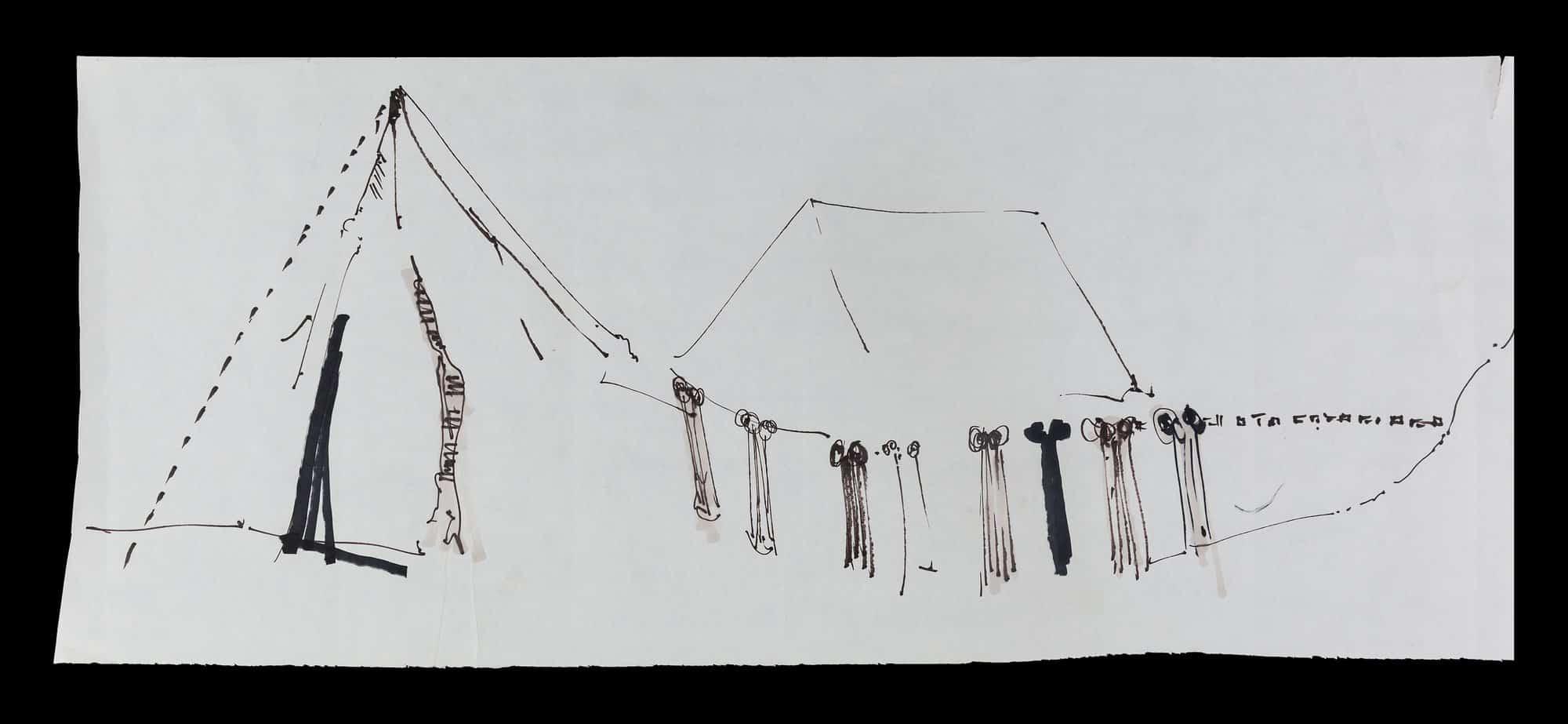

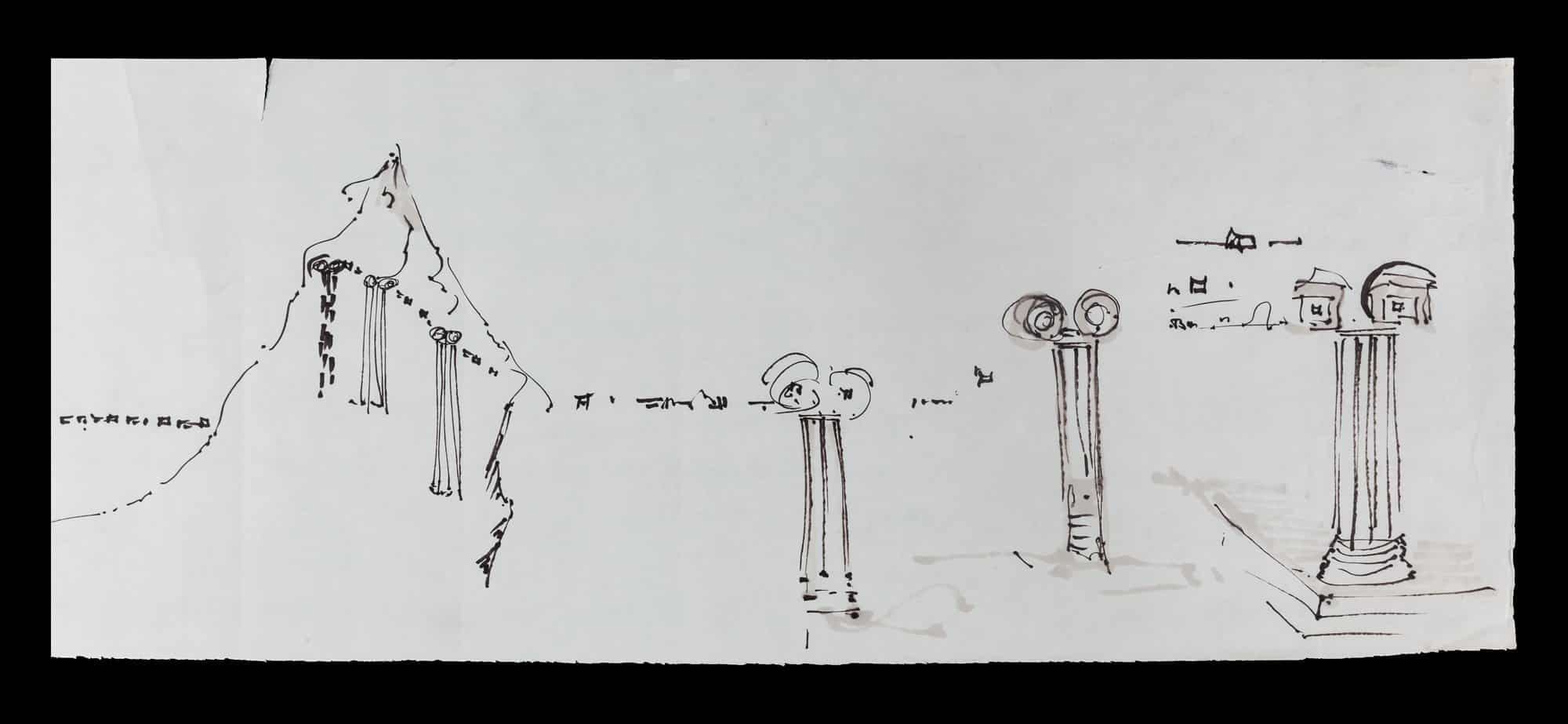

During a poetry reading at St Mark’s Church in the East Village of New York in 1973 Gordon Matta-Clark announced that he would draw on a roll of butcher paper an account of the history of architecture with a single long stroke of the pen. At the conclusion he would tear off sections as gifts to the audience, which no-one present chose to claim. This is apparently the first sheet from that roll. It is closely allied to a plate of Gottfried Semper that he would have remembered from his five years of study in the Architecture School of Cornell University, Matta-Clark’s rapid-fire lines and points move, sometimes in perspective and sometimes in elevation, from the tent and primitive hut to the first expressions of the classical column, capturing the formal genetics of drawing as he recounts the genesis of western architecture.

Matta-Clark was the son of the charismatic Chilean Roberto Matta, an architect who, after a stint with Le Corbusier, turned to painting, and became a central figure in the Surrealist movement. His mother Anne Clark was an artist; her lover for some years of Gordon’s childhood, and in many ways a second father, was Isamu Noguchi, the sculptor and designer (and son of the great Japanese-Californian writer Yone Noguchi), an era in which Noguchi was deeply involved as a designer of dance performances with Martha Graham. Anne went on to marry the leading film critic Hollis Alpert. He was named after his parents’ great friend, the mystical surrealist painter Gordon Onslow-Ford, who with Matta and Robert Motherwell had undertaken the famous 1941 journey into Mexico in which they first defined the tenets of a new school of painting and sculpture, grounded in psychology and the cosmic, which we now know as Abstract Expressionism. His childhood was divided between Santiago de Chile, where his first language was Spanish; Paris, where he and his brother Sebastian sat at the feet of Andre Breton; and New York. Gordon himself stayed at Cornell for a year after completing his architectural training in 1968 to work with the team of graduate students who put together Thomas Leavitt’s great Land Art show of 1969, and in particular with Robert Smithson’s salt installations and Dennis Oppenheim’s cut through the ice of the lake.

One could scarcely imagine a more heady or certain background from which to produce an artist for whom any taboo was a challenge, and all conventions existed to be undermined. His own first works were experiments in shaping primitive sculptural forms from an impossible amalgam of unlikely materials. His second involved an invitation to a friend to become the subject of cannibalism. He fried photographs in a pan, and served platters of bones to the customers of his restaurant Food. He sought architecture in the ‘narchitecture’ of manhole covers and underground water systems, and art in the fearfully dangerous aerial dance of his body, whether between trees (at Vassar College) or (in Kassel) on the flimsiest skein of a spider-web tower. Both patient and antic, every work was ephemeral; and he was profoundly happy to leave entirely open the matter of what constituted art or architecture – the act of making it, the remnants or debris left after producing it, the film that recorded an activity, the memory of the viewer who chanced upon it, or the sketch of an idea that it began with.

Yet throughout a wildly inventive career of less than a decade, made brilliant with his words, unconscionably glamorous with his presence, and profoundly unsettling in its challenges to the derelictions of society in its contempt for the forgotten and its scorn of the environment, it is Gordon’s drawing of architecture in some form that provides the glue. He began with a series of ‘electric’ drawings, echoing his father’s, that endeavoured to locate dynamic form. He sketched out and measured the lines of all his interventions in his notebooks. He drew architectures with a razor through the pages of sketchbooks. He constructed towers with his head of hair. He disturbed through broken patterns, with an air-gun, the windows of the Institute for Architecture and Urban Studies, reproducing the shattered glass patterns of a devastated South Bronx tenement on the face of a pinnacle of design privilege. And again and again, using a little chain saw and usually suspended from a fearfully simple block and tackle, he drew in the three dimensions of light cast through cuts between the walls , floors or roofs of unregarded buildings. And he ended with pencil again in hand, in a set of heart-rending voodoo sheets in which the art of drawing is called upon to conjure up a battle between his antibodies and the cancer cells that would shortly destroy him.

– Robert Smithson