Pan Scroll Zoom 5: Andrés Jaque

– Fabrizio Gallanti and Andrés Jaque

This is the fifth in a series of texts edited by Fabrizio Gallanti on the challenges in the new world of online architectural teaching and, particularly, on the changing role of drawings in presentations and reviews. In this episode Fabrizio interviews Andrés Jaque, founder of the Office for Political Innovation and Associate Professor of Professional Practice and Director of the Advanced Architectural Design Programme at Columbia, GSAPP.

As the Pan, Scroll, Zoom project evolves and gains momentum, it might become the basis of a small publication. We welcome comments and ideas at editors@drawingmatter.org.

Andrés Jaque: You know what? Even before we start this conversation, we should briefly consider what are the most important things that we have found out and understood during these months of confinement and remote teaching.

Fabrizio Gallanti: Yes – what exactly do you mean by that?

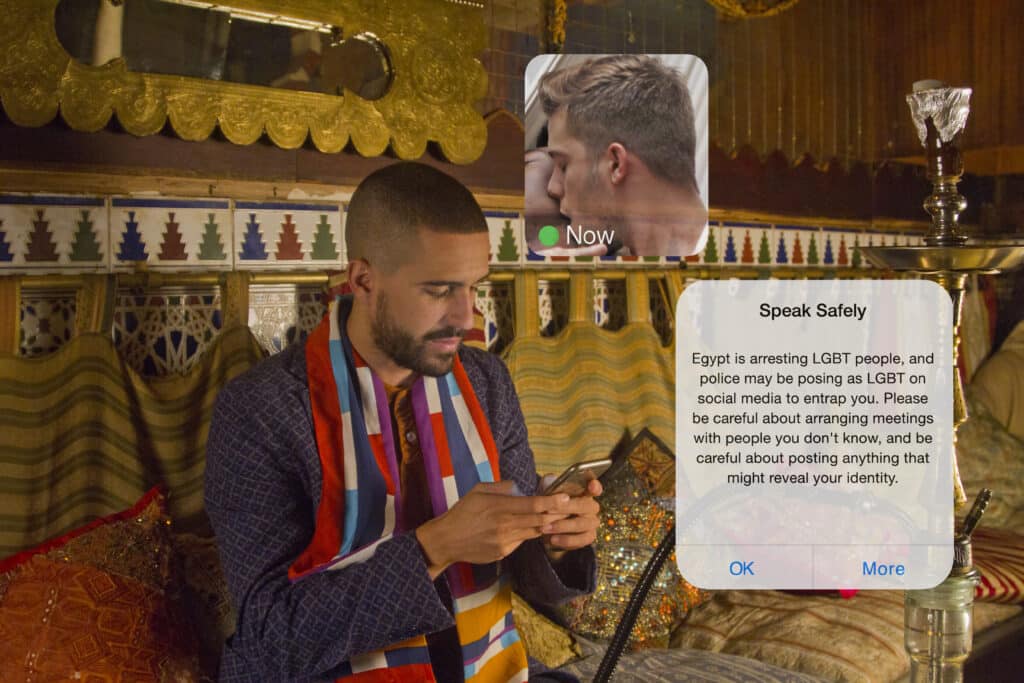

AJ: Well, there are issues at the core of this series that are eminently related to our field, architecture, and those we will discuss later. But the discussion of how our context is changing, dealing with the evolution in the way we interact, is deeply affected by nuances, of the implications of which, in the near future, we are not yet fully aware. Across research-based universities there is a broad discussion about how we should use digital tools of remote learning and teaching when we operate outside our usual realm, how we should intervene within territorial jurisdictions that treat quite differently such topics as freedom of expression or censorship. The discussion of this crucial question will shape the future of pedagogy. When we teach and conduct research in a specific location, the faculty, the administrators and students, no matter what their nationality or background, are subject to the legislation of the place. So, international students, for instance, function within a pre-determined legal framework. But what happens when a course is delivered through Zoom or other equivalent media, and the students or professors are located in countries where different political systems are in place, where ultimately freedom of expression is not always as guaranteed as we like to imagine? Systems of censorship or policy over voices of citizens are very different, and as we know how companies such as Facebook or Google control our data and might be willing to transfer them to certain states and other organisations, we should be concerned. What happens when entire chunks of pedagogy have, all of a sudden, been outsourced to private companies such as Zoom, over which we have little control and which we know operate precisely in the loopholes that exist between different national legislative systems, doing things that, while illegal in country A, might be legitimate in country B? I would dare to say that creating milieus and infrastructures where knowledge can be collectively produced and challenged under political and democratic protection might become the main role for universities to play in the present and definitively in the future.

FG: In fact, numerous universities are conducting extremely careful due diligence about certain software, to avoid the risk of being exposed to espionage in case the data were to be stored in servers within countries that are lax about privacy issues or where it is literally the state itself that runs rogue operations. Many companies that provide online teaching tools are now clearly stating on their websites where the data of their users is kept, as well as what security protocols they are adopting. We can agree that the drawings of an architectural design studio might not be great objects of desire, but some PhD research in the areas of engineering or advanced biology might be, instead, extremely valuable.

AJ: The fact that pedagogical interaction is now broadly mediated, registered and archived in privately owned infrastructures, of which we know little about how likely they are to share information with third parties, opens questions about the capacity of universities to provide a safe space for academic speculation and critical engagement. I think that the current scenario of online teaching imposes on us the need to rethink many of these questions. We are well aware by now that screening and intrusions on one’s privacy are also more frequent than we realise. I know that studying processes such as the one we are discussing have been one of the focuses of scholars such as Laura Kurgan or James Bridle, and that they are committed to exploring the importance of universities investigating these matters.

At GSAPP in Columbia University during the Fall semester, we have initiated a hybrid format of teaching – the campus is subject to very tight controls to prevent the spread of Covid-19. There is a very interesting and completely novel educational atmosphere, where off-line interaction has become more planned and where serendipity is progressively moving into the space of online interaction, where new forms of informality are emerging. It is a very interesting shift, which has occurred in just a few weeks.

FG: Knowing how you interweave research, teaching and your own practice as a designer, by generating very powerful representations, I wonder how you have organised your courses. And I am interested to understand how architectural drawing has been mobilised in your teaching.

AJ: We will all be witnessing most of the changes in the next weeks, once we collectively resolve the urgent and immediate practical issues: timing, what software to use and how to overcome the impossibility of being gathered in the same physical space. To me what has been most poignant is how it was clearly revealed that architecture operates almost as a sensory organ. The Covid-19 pandemic has accelerated what I feel is a growing collective concern to consider architecture as a means with which to address a set of crises – climatic, societal and territorial – that should be put at the centre of our perception as a discipline. In particular, the collapse of the model of globalisation, based on the acceleration of movement and dynamisation of capital, has become obvious and we realise how much that model was flawed even before the pandemic. The neo-liberal idea of a seamless circulation of goods and capital has vanished in a few weeks, and so has the idea of architectural design as neutral, ubiquitous and oblivious to the conditions prevailing in specific territories.

The second crisis relates to the city. Until recently, we have accepted the myth that the city was the solution to every problem, whether environmental, political or economic. One can see this in all those lectures of the ‘Urban Age’ series, sponsored, somewhat suspiciously, by banks and corporations, or the rise of mayors as the new heroes of our world, capable of doing what was impossible at a national level. A good example of this has been Sergio Fajardo in Medellín, often seen as close to the central government of Colombia. We came to the point of repeating that the ‘city was the answer’ to any problem! Well, no city could have faced the pandemic alone, or could even address issues of climate crisis and inequality, without the collaboration of structures of governance and design that operate on both territorial and trans-national scales, and on the much smaller scales in which seeds, genes and molecules are being designed and regulated now. The city is not a spatial or societal figure that can effectively comprise the conflicts the world faces now.

But these are not abstract ideas. All these crises have emerged and become visible in the past months, mixed with crucial issues of inequality: while many of us would be allowed the privilege of staying at home, many others – often members of racialised communities – were delivering food and experiencing a higher risk of getting infected.

Forgive this long introduction, but I think that within this scenario, the question of architecture and representation has become even more fundamental than it was in the past. In my reading, drawing, historically, has never been a tool for simply illustrating, depicting or symbolising reality, but instead how ‘representation’ has functioned is simply as a ‘parliament,’ therefore as complex systems that allow for the coexistence of multiple subjects, so that they are installed in the area where decisions are made. Drawing is intrinsically connected to the process by which architectural artefacts unfold their agency and negotiate it with the agency of multiple other entities.

When in my office we designed, more than ten years ago, the Never Never Land House in Ibiza, we drew with extreme accuracy all the shrubs and trees present on the plot, paying attention to and depicting their roots and the shape of each branch. It is only because these living entities were made visible through the act of drawing that then they were taken into account in the design and during the construction phase. Exceptionally, we failed to include two trees out of more than thirty in our plans, and these two trees were cut down the same day that construction started. Neither we, nor others in the team, found a way of preventing them from disappearing. There is no permanence without representation; or put in a Latourian way, no assemblage without assembly. It was a clear lesson for me, that I have ever since tried to transfer within pedagogy, to find the space in which to push forward even more radical topics that might have to find points of compromise within the professional practice.

FG: It is interesting that you always use the word ‘drawing’ in the singular, because if I were to characterise your approach, I can clearly visualise how just one drawing is always enough to convey all the ideas of a project. Similarly, when I participated in the final reviews of your design studios at the GSAPP, I also noticed how the students always presented a unique, extremely synthetic drawing, charged with infinite layers of information. They reminded me, often, of the illustrated pages of the Encyclopédie.

AJ: I think that architecture is just ‘societal articulation’. What I mean by this is that architecture, as an ecosystem of practices and technologies, comprises all that facilitates and manages the entanglement between the different entities that constitute societies. From this perspective, I don’t see any conceptual difference between the political status of a building and that of an architectural drawing. They both operate as assemblages of multiple heterogeneous realities that, through these architectural artifacts – buildings, architectural drawings or others – gain a platform where their fragile state of coexistence can achieve durability.

For me architecture does not illustrate the social, it is in itself the social. When we draw both in our office and in the studios that I run at the GSAPP, we consider architecture to be, at all scales and in all media, a societal assemblage, where multiple positions, conflicts, alliances and solidarities converge. Any entity is multiple. Like in Joseph Kosuth’s works, a dog is both a body where blood circulates and an entity that is registered by a municipality as the pet of a human caretaker. The dog is the assemblage of both the record and the body. The drawing is intrinsically part of the building, not its portrait. Representation in architecture is not about creating subsidiary images of an entity, but rather providing that entity with a presence in multiple sites of criticality and action.

The conditions by which many ‘others’ are incorporated into buildings or drawings will become even more of a crucial issue for architects at a time when our culture and politics are entering a climatic and therefore relational paradigm. Climate and relationability require architecture to redevelop the way it operates as media, since they are both aspects of reality that are very difficult to be sensed by humans now. Architectural know-how has developed over centuries very efficient tools to face specific aspects of reality, for instance budget and costs. Yet it lacks the capacity to confront other sensitive issues such as social inclusivity, ecological impact or the consequences of architectural operations on wider territories, through the chains of supply or the organisation of labour. If we analyse dominant tools such as BIM, it is clear how that digital suite is rather useless at incorporating the political issues that now have become central and inescapable.

Both in my office and at the programme I direct at GSAPP, we are trying to mobilise drawing as a tool of dissidence against these softwares, such as AutoCAD, Revit, Rhino, that are conceived to serve some interests to the detriment of many. I always notice that all the interesting architecture studios that we know always use digital tools almost against the logic with which the software was originally created.

FG: And are the students also aligned to these forms of resistance?

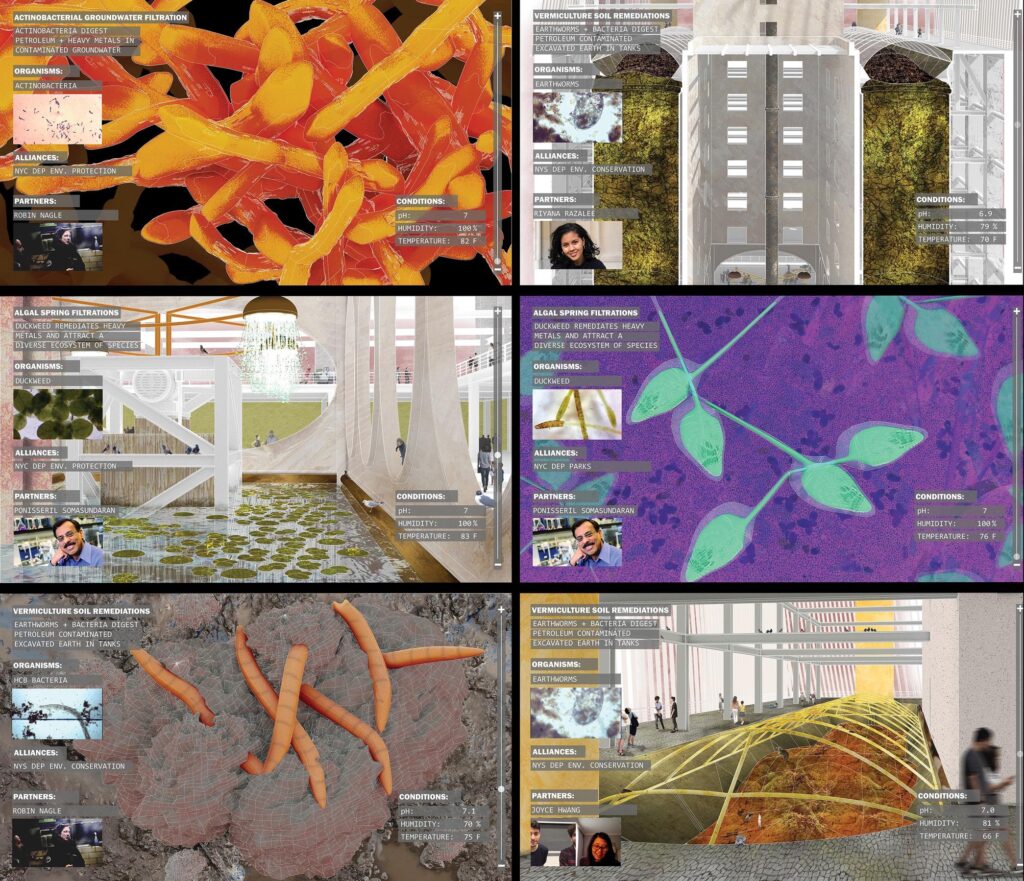

AJ: During the last semesters we have been analysing how Manhattan has been, at least since the 1920s, progressively expelling any undesirable components from its territory, becoming what it is now, a polished playground for advanced capitalism. Animals have been pushed out, as something that is deemed contaminated. Now garbage and waste end up in Kentucky, for instance. The project by Frederico G. Castello Branco, Frank Mandell and Christopher Stavros Spirakos proposes to dig the toxic ground under the current development of Hudson Yards, using it as a resource that stays in the city and is processed by a new ecosystem, which they have included in a skyscraper. Currently Hudson Yards is being built by creating an artificial new concrete ground, a gigantic thick slab that covers what is below, a solution that is just cosmetic (and cheaper) and does not improve the area.

The students collaborated with more than twenty stakeholders: NGOs, environmental lawyers, scientists, citizens’ organizations, animal activists. What is toxic for humans might be a nutrient for certain bacteria and thus trigger processes of remediation, also allowing for other animal and vegetal species to return to the city.

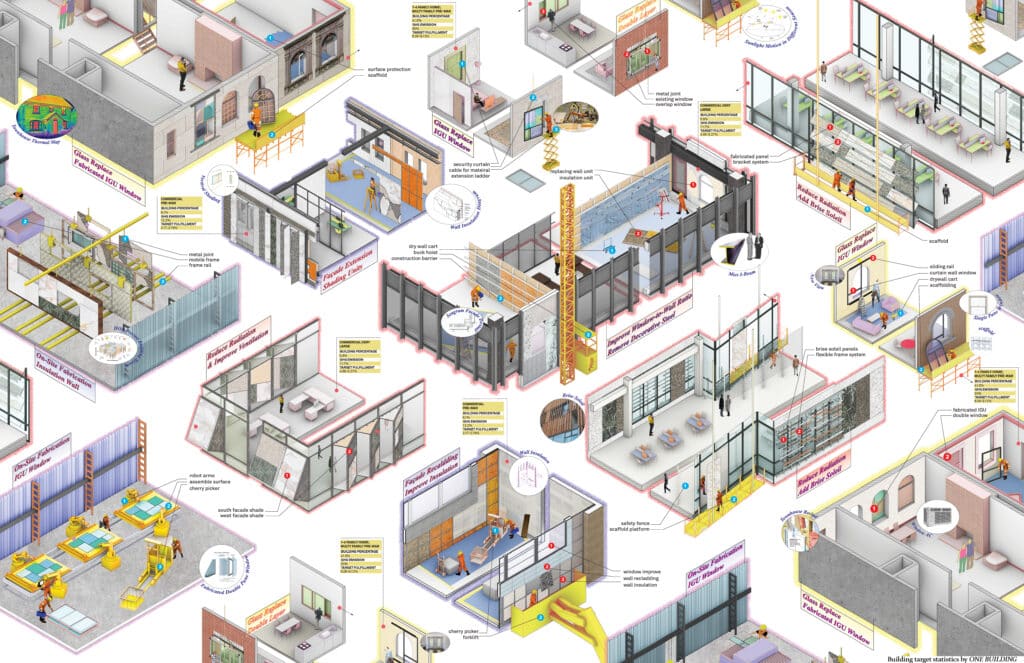

This other design by Yining He and Xinning Hua [below] is also very interesting, as it can be read as a reaction to the current debate about the Green New Deal. Every single day New York produces tons of waste derived from building and demolition. The students generated a visual catalogue of everything that gets demolished during one day: facade systems, windows, ceilings, walls, pipes, internal partitions, etc. The project becomes a sophisticated choreography where these materials are reused to improve the energy efficiency of other buildings being refurbished. As the proposed operations require a more specialised labour force, the project also guarantees better salaries for workers. These are the kind of drawings that interest me now as they bring in all the associate partners that make a project feasible.

In general terms, I am very optimistic about the current generations of students. When I studied myself, many were obsessed with the idea of personal success, a caricature, actually, as in Oliver Stone’s Wall Street. Talking about politics in architecture back then invariably made some people angry. Now that attitude seems to have completely disappeared. What is interesting is that there is now a collective and shared understanding that architecture is a political practice, an attitude that has come to the universities from the real life of everyone. Students have been hit by 2008 and now by Covid-19, so they have a much healthier relationship to consumerism, for instance, and they pursue completely different models of becoming architects. Priorities have completely changed.

FG: So the drawing is also conceived as a tool with which to negotiate – therefore it needs a style of expression that can also communicate to non-specialists. Was it something that students were induced to do?

AJ: Yes, to me it is always important for the drawing to be very large and not easy to saturate; that is to say, it is a platform that allows for the addition and modification of the data it articulates. A drawing should work as a platform that leaves room to imagine future transformations and changes, therefore it should not be entirely finished or extremely specific in every single detail. I see a drawing rather as a palimpsest that allows for experimentation, changes, corrections, alterations or for simultaneously allowing different possibilities. The most interesting moments for me in the Zoom and Miro experience are the instances when different participants can draw simultaneously on the screen. During critiques and reviews this possibility allows for the documents included in a presentation to be annotated, sketched upon, changed by many, actually functioning rather better than during conventional in-person presentations. When we used to do drawings by hand, we often tried to produce very large sheets, almost furniture pieces, real tables of negotiation. A drawing needs to be very large, as you want to have people seated around it. Miro of the annotation function in Zoom allows students to a certain extent to replicate that sensation of collectively working on the same template. In any case I do not see a big conceptual difference between pencil and computer. I agree with Michel Serres, who stated that cartography had not significantly evolved over centuries, and I would say that the same can be said of the architectural drawing. And it is not by accident that the annotation function of Zoom is the first function disabled when Zoom-bombing is intended to be prevented.

FG: If we consider a movement in the opposite direction, in your studios, drawings are also used to incorporate, within architecture, data and information coming from other areas of expertise.

AJ: My studios are always conceived in the same way. We determine a reality that is traversed by an intense political conflict, and we address it using the instruments of architecture. Currently we are working on the Lincoln Center in New York, a place that every architect loves. But actually it is a horrible place, because in order to build it, 18 housing blocks occupied by a predominantly Puerto Rican population were destroyed and a large number of these citizens ended up deported, as Robert Moses stated, ‘where the rail ends,’ in Rockaway Beach, on land already prone to floods every year. I am interested in starting with a unresolvable conflict, where architecture finds itself in difficulty. So the first action is to use the drawing to bring back the presence of these communities, the traces of the past but also the continuing consequences. When someone asks ‘Why are African American or Latino communities in New York often more exposed to the consequences of climate change?’, the answer is just there in front of you: they have been expelled to the riskiest places, where they were exposed to environmental vulnerability, almost below sea levels. It is a process where the drawing is almost like in the movie Poltergeist – it reveals presences that have been historically neglected and made invisible.

FG: What is the output? Is it a sequence of analytical drawings?

AJ: No, actually, again, it is a singular item, a three-dimensional file where everything is kept together. I still believe that plans and sections are capable of concentrating huge quantities of information. I am also interested in the possibilities of using drawing to establish comparative readings. For instance, if one overlaps the sections of the vanished blocks of what was dubbed San Juan Hill with the new houses for the displaced community built in Rockaway, observing the foundation details it becomes obvious how there are issues with the water table and the risks of inundation. A digital three-dimensional model allows the generation of what I call ‘orthodox’ drawings, almost as MRI scans, plans and sections that can be read as forensic evidence of the multiplicity and controversiality that reality is made of.

The challenge for architecture is not to quickly find an easy solution, but rather to overlap the multiple layers of a place, in order to advocate that ethics and design be mobilised together in order to provide a sense of collective urbanity and spatial, material and relational justice. In the drawing, almost magically it becomes possible to allow for different realities to coexist and the contentiousness of coexistence can be addressed.

My obsession, when I try to connect the act of drawing and the political function of architecture, is how to produce representations that are not easy to saturate, and therefore do not automatically promote exclusion. That is why I hate such an excluding narrative as the framed lineal progression of the Eames’ Powers of Ten. I remember in my first year, when we started the course of drawing by hand, that it was important not to exercise too much pressure on the pencil nor to rub too hard with the eraser, in order to play with a wider palette of greys rather than just black or white. I consider design needs to self-impose a condition of unfinished process: therefore it needs to progressively allow for new subjects to be incorporated over a slower timeline, as Isabelle Stengers proposes with her notion of cosmopolitics.

I am quite fascinated by the book Slow Violence and the Environmentalism of the Poor by Rob Nixon. Communities have for far too long been exposed to forms of slow violence that are almost impossible to detect: I think that the architectural drawing is an act of resistance that can make moves to try to stop and reverse such violence.

– Fabrizio Gallanti