Peter Wilson and Mark Dorrian in Conversation – Part 1

– Mark Dorrian and Peter Wilson

This is the first part of an edited transcript of a conversation held in Thurloe Sq, London, on 25 July 2020. Peter Wilson’s exhibition ‘Indian Summer and Thereafter’ had opened at Betts Project the previous evening.

Mark Dorrian: What led you to architecture to begin with, Peter? You began studying at the University of Melbourne in Australia …

Peter Wilson: My first three years were at Melbourne University, there was no Bachelor then—after three years the tradition was to take a year out. I think of myself as still on an extended year out, forty-five years later.

MD: What was the pedagogic approach of the architecture school?

PW: I believe I was quite lucky … Australia was then at least ten years behind the rest of the world and had not yet updated to sociology-influenced teaching as in America or in Europe. Our first year was a sort of terminal echo of Itten’s Bauhaus introductory course – making tactile patterns or labyrinths to follow with your finger, using rough surfaces like sandpaper, or soft, like velvet. Even razor blades were allowed [laughs]. I really enjoyed that. We also had to make little balsa wood frames to suspend white cubes on fine cotton threads—3D composition. I don’t think they realised that they were doing something quite profound.

MD: I suppose it was a year system, where you were taught in a whole cohort?

PW: Yes, but we had to do courses like chemistry and I was really bad at science. We even had computer programming using punch cards—my ineptitude there was obvious, regularly mis-punching a hole.

MD: Did you actually have to make the punch cards?

PW: Yes, they gave you a stack of cards and you had to make the programme. I punched the wrong hole and kept the computer—which was as big as three rooms—thinking all night. They got really upset with me and wouldn’t let me at it again. The reason that I landed there was because I had always painted as a child, my escape from my sport-obsessed family. An aunt had given me a ‘how to paint’ book, which instructed [readers] to paint by north light, so I dutifully did. But it was a European book, so I spent a good few years painting in blistering Australian sunlight and could hardly perceive colour differences.

MD: So, after three years you spent a year in practice … and that was with Robin Boyd?

PW: No, after two years I worked during the summer for Robin Boyd. Actually, the reason I got into architecture was that when I left school, I wanted to be a painter and I started art school but I was a bit taken aback by how bohemian it was. I then went to the architecture school, had an interview, and was told ‘oh painting … you can do everything here, you can design buildings and also paint’. It was a complete untruth, but I liked the idea and from the first week I was really happy discovering that drawing in line and having geometric restrictions gave my drawing talent a framework.

MD: It’s interesting to hear about your encounter with the computational punch cards of the time as well, because they are so physical and, in a way, spatial—patterned and compositional …

PW: Yes. People were then aware that computers would play a big role in architecture in the near future, but were not sure exactly how. At that time in Melbourne there was also a great interest in Japan. One professor had actually been there and Robin Boyd obviously had strong Japanese connections. The architecture school—the one before the current building—had a little Japanese garden down one side. I even got my old Dad, not long before he passed away, to attempt a Japanese Garden in our urban fringe elysium. My friends called me Kenzo because of my obsession with Tange’s early concrete works. Around 1985, Toyo Ito asked me to design a piece of furniture for a Tokyo exhibition. I did a sofa that had a wooden seat and metal backrest, which were both perforated. The Japanese call perforated metal ‘punching metal’—there was perhaps a memory of those computer cards in my Punch Sofa.

MD: Did you have Japanese architects visiting the school and speaking?

PW: No—the only one who really had contact was Robin Boyd …

MD: Would you say the main orientation of the school at this time—the end of the 1960s – was still towards Europe?

PW: Yes, but also very much towards America. The RAIA had a visiting lecture series—people like Giancarlo de Carlo or Peter Blake, who talked about his book God’s Own Junkyard. I think bits of Venturi had seeped in at the edges. Robin Boyd had read Venturi and built a Pop building, which horrified everyone. The great aesthete dropping a giant fishbowl on top of a fish restaurant.

MD: The fishbowl as a ‘Venturi duck’. Did Boyd teach you in studio prior to you working with him?

PW: No, he didn’t teach and sadly died in his 50s. He was an absolute gentleman-architect. I was enormously impressed when I met him in his office. It was a Victorian terrace. In his room at the back, every surface was painted strawberry pink—it was just fantastic, a revelation—I’d never been inside such an exquisite aesthetic atmosphere. He sat behind his desk, a very delicate gent with blond hair—very polite, very formal. The reason he took me on was because of my drawing, but also because of an old boy network: I’d been to the same school he’d been to. One reason to leave Australia was to get away from that.

MD: What was his own training? Was he educated at the University of Melbourne?

PW: I don’t know where he studied. He was of the generation that was in the Second World War, in the army, like my father. He came from a family of artists—Arthur Boyd, an Australian painter, was his cousin. The Boyd family were the aesthetes of Melbourne. When I grew up, there were Robin Boyd houses scattered around the suburbs, and my only understanding of architecture was my parents saying ‘that’s a Boyd house’, and ‘that’s another Boyd House’. There was one up the road from us, the Troedel House, which I wrote about some years ago for an exhibition in Berlin.[1] It was my first experience of a modern house—my parents’ interior was all sort of fake English, my father being a Yorkshireman.

MD: And what was that experience like for you?

PW: It was a house that didn’t seem to have any walls, very strange, open plan, and a stepping-down landscape interior. One big glass façade with a pergola screening out the sun. Robin Boyd wrote somewhere that a modern man must drive a Studebaker and Theo Troedel did. His wife Yvonne had a red Mercedes sports car. As one of my mother’s tennis girls she would drive up, looking like Jacqueline Onassis, a big 1960s black perm bobbing above the red bullet.

MD: What were Robin Boyd’s points of reference?

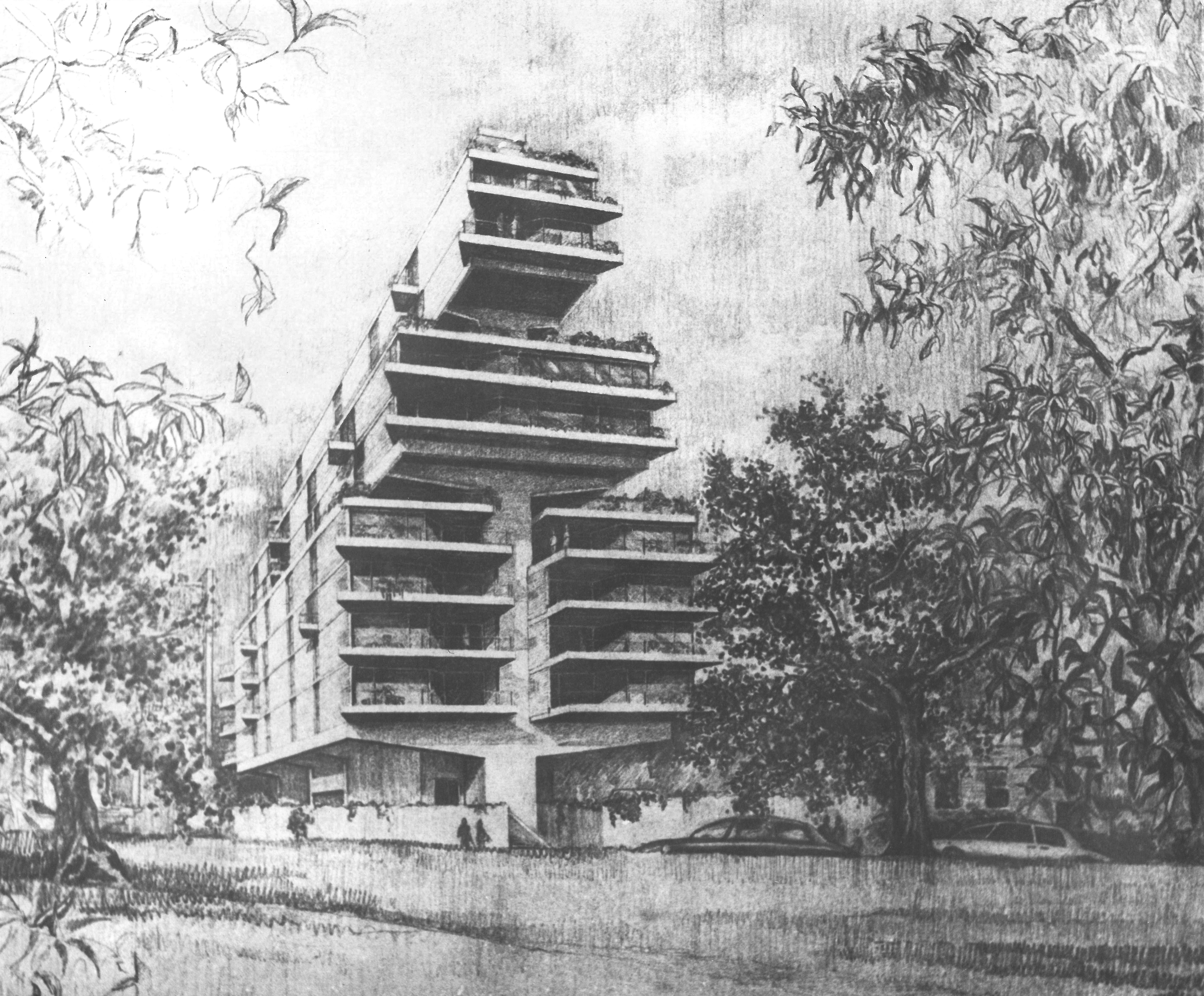

PW: He wrote New Directions in Japanese Architecture, a 1968 Thames & Hudson book. It was the first English-language book on Metabolism. That’s a drawing I did in his office. (Fig. 1) It was the second version of a sort of Metabolist megastructure. He was also pal of Gropius but frustrated that he’d never built a public building—except Jimmy Watson’s Wine Bar. His ex-partner, Roy Grounds, not as good an architect but a much better self-promoter, built the National Gallery of Victoria. He had a really cheesy explanation, claiming that he first drew the figure of a rectangle enclosing a circle with a stick while strolling on the beach—eureka!—and that was the plan.

MD: How long did you spend in the office?

PW: Probably 8 weeks … a really hot summer as well, drawing with a sweaty hand. No air-conditioning.

MD: Was this the point when he talked to you about the Architectural Association?

PW: Yes. He would come in and lean over the board where I was drawing and tell me what to focus on and what was not right with the light or the perspective. There was a conversation about the gum leaves—how they drip in winter. And I maybe asked him something about Japan, so he spoke a bit about the Metabolists but then said, ‘what’s really interesting these days is Archigram and the AA in London’.

MD: Had he been there?

PW: I don’t know. He wrote for the Architectural Review, so he had good contacts in London. He was a networker.

MD: Had you been aware of the AA before that?

PW: No. The following year Dennis Crompton and Ron Herron came to a conference in Australia and performed the Archigram opera. I sat in a row behind an architect called John Andrews, the one who did the Harvard Graduate School. He was an Australian who had won a big competition in America and had come back to be a star in Australia. He wore a red boiler suit proclaiming, ‘I am a hip modern man’. He was really guffawing and laughing—‘this is not architecture’. And one was offended and took their side. Not long after I made a plug-in city with table-tennis balls as capsules, which my sporting family thought a waste.

MD: Did you have predecessors travelling from Melbourne, or even Australia, to the AA at the time?

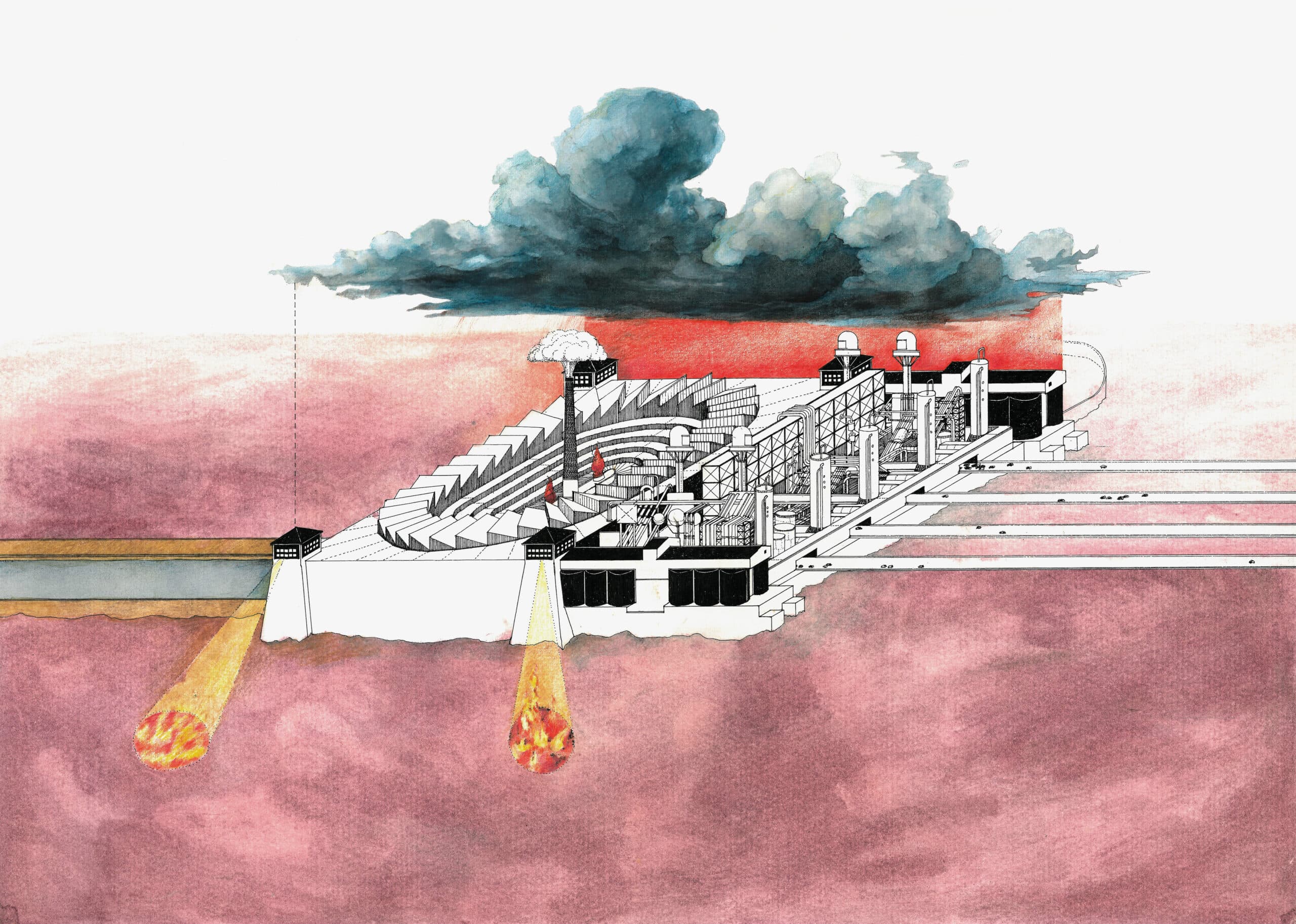

PW: I don’t think so. I arrived with Jenny Lowe. We had worked together in Melbourne, even once making an inflatable. I still have a slide of this big orange thing lurking in the Australian bush—inflated with a vacuum cleaner and hot like a sauna in the Australian sun (Fig. 2).

MD: Did you travel to the AA immediately after the period in Robin Boyd’s office?

PW: I did one more year at Melbourne University, and then it was the year out. There were maybe ten or fifteen people from our year who went to Europe as interns.

MD: To different locations?

PW: One went to Switzerland and worked in Zürich in the office of Justus Dahinden, a 1960s modernist. There he had contact with Alfred Roth, who was gay and had worked with Le Corbusier. Visiting the Roth house was extraordinary—he proudly showed us his Mondrians on the wall, one of which had disappeared with a departing boyfriend.

MD: What was it like arriving in London and the AA?

PW: Turning up at the AA on my first day in London, I was just totally enamoured—it was like a circus. I had bounced from the extreme periphery to the epicentre. I stayed at first with friends of my family in Blackheath. Everything was spatially so different to Australia. It was winter and it was cold, people wandering around in duffle coats and stuff, frost on Blackheath and little houses around it. My hosts were living in low-rise modernist housing, I think across the road from where Peter Moro lived. I finally got a job with Peter Moro, who had worked with Leslie Martin on the Festival Hall, but at the time there were no theatre projects in the office, only housing in Lambeth. Before that I worked a couple of weeks with Zeev Aram on the Kings Road. He was a London personality of the 1960s, a bit like Conran, also dealing in modernist furniture—Eileen Gray, etc. After that I jobbed a few weeks for Theo Crosby at Pentagram.

MD: I’m interested in not just the studios you took at the AA, but how you chose. How did you orientate yourself within that, coming from the outside?

PW: When we arrived, we got to know AA people and it was the time of squatting. Jenny and I got in with a guy who managed the projection technology for lectures at the AA and we squatted a house in Crystal Palace. We lived there while I was working and went to AA lectures in the evenings. Peter Moro’s office was around the corner, just off Charlotte Street.

MD: You had a period of acclimatisation.

PW: Jenny and I did our version of the European Grand Tour the summer before starting in Bedford Square.

MD: Where did you go?

PW: We bought mopeds in Amsterdam—being Australians we thought, yeah Europe’s small, a moped will do [laughs]. And we rode the mopeds from Amsterdam to Copenhagen, which took some time. A wide flat polder landscape with NATO Starfighters booming overhead. Then we headed for Italy. Realising that it was going to take weeks, we skipped northern Germany by train. We must have flashed passed Münster.

MD: You left the mopeds behind at that point?

PW: No, we had the mopeds on the trains. We got off at Wuppertal to see Engels’ home town, with the upside-down railway over the river, and I promptly got my moped tyre trapped in a tram track and fell off. Then we proceeded down the Rhine Valley to Switzerland to see our friend in Zürich and Le Corbusier’s then brand-new Heidi Weber Pavilion. After that we crossed the Alps on mopeds—we had to walk uphill the whole day with them on full throttle. They could just pull themselves up. And the next day we rolled down into Italy.

MD: Amazing. Were you carrying a lot of pack?

PW: An army sausage thing with all out stuff squeezed in, and a sheet of plastic because it rained a lot and we slept in forests. We skirted around Milan and made for Genoa, took a train to Florence and back, and were just starting the return to the AA along the Ligurian coast when a bus knocked Jenny off her moped. She was in hospital with concussion for two weeks. It was really traumatic. I hung around exploring Genoa, and then we flew back. We used to say jokingly that she became a surrealist after her Italian bump on the head.

MD: In terms of the units that were being offered, what was available and how did you decide?

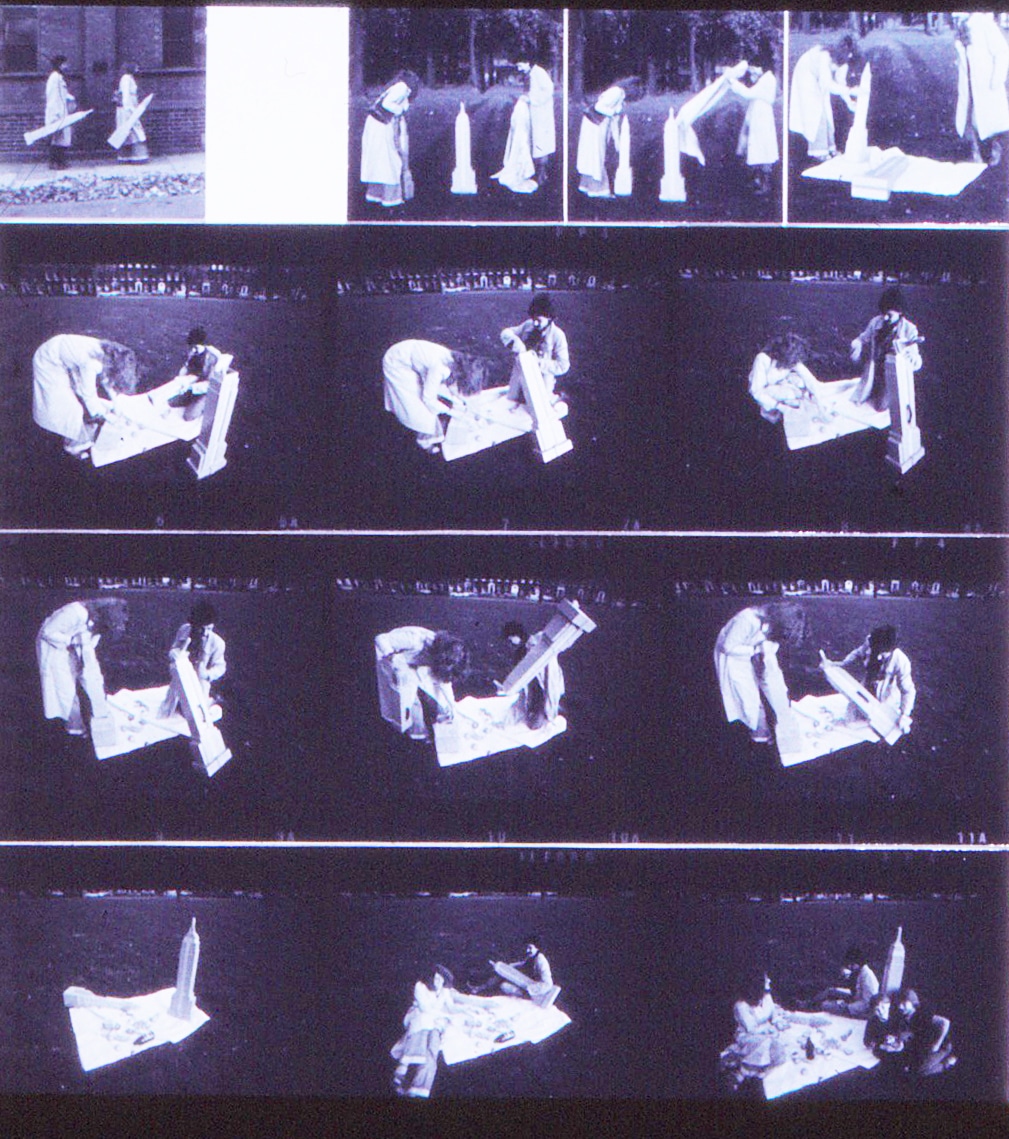

PW: In our fourth year the unit system was not yet in place. Alvin Boyarsky introduced it the following year. Instead, there were various programmes offered, so one could choose a teacher. Our first very short exercise was with Piers Gough. We had to design a ‘Sexy Stair’. Jenny and I worked together, finding a cardboard box and lining the inside with pornographic photographs. We then painted a little stepladder pink and hung the box from the ceiling with a hole cut in the underside—the viewer had to climb to the box and put their head in it. I guess it was performative, maybe even immersive, but also pretty naïve … we were aware of current conceptual art but didn’t quite understand it—or even our own milieu, for that matter (Fig. 3).

MD: What year was this?

PW: 1972. Then we signed up for another programme—a ‘utopian village’ with Colin Fournier, who had worked with Archigram on their Monte Carlo project. Alvin had invited Colin and Bernard Tschumi to teach at the AA—two French speakers. Basically, one produced almost no work at all … taking it all in was a full-time occupation. Then, over the summer, I hitch-hiked from LA to Vancouver and across the prairies to New York. Coming back in the fifth year we were told we would have to choose a unit. But myself, Jenny, Nigel Coates, and Jeanne Sillett were the tearaways who didn’t want to sign up for just one unit … I signed up with two, Dalibor Vesely and Elia Zenghelis, and Jenny signed up with three.

MD: So how did that work? Did you sign up for half the year each?

PW: I did a project with Dalibor first. It was a based in Cambridge, so we all explored Dalibor’s future haunt. Then Jeanne and I moved across to Elia, to put down roots.

MD: What motivated the choices? Why did you want to work with Dalibor … was it the unit brief?

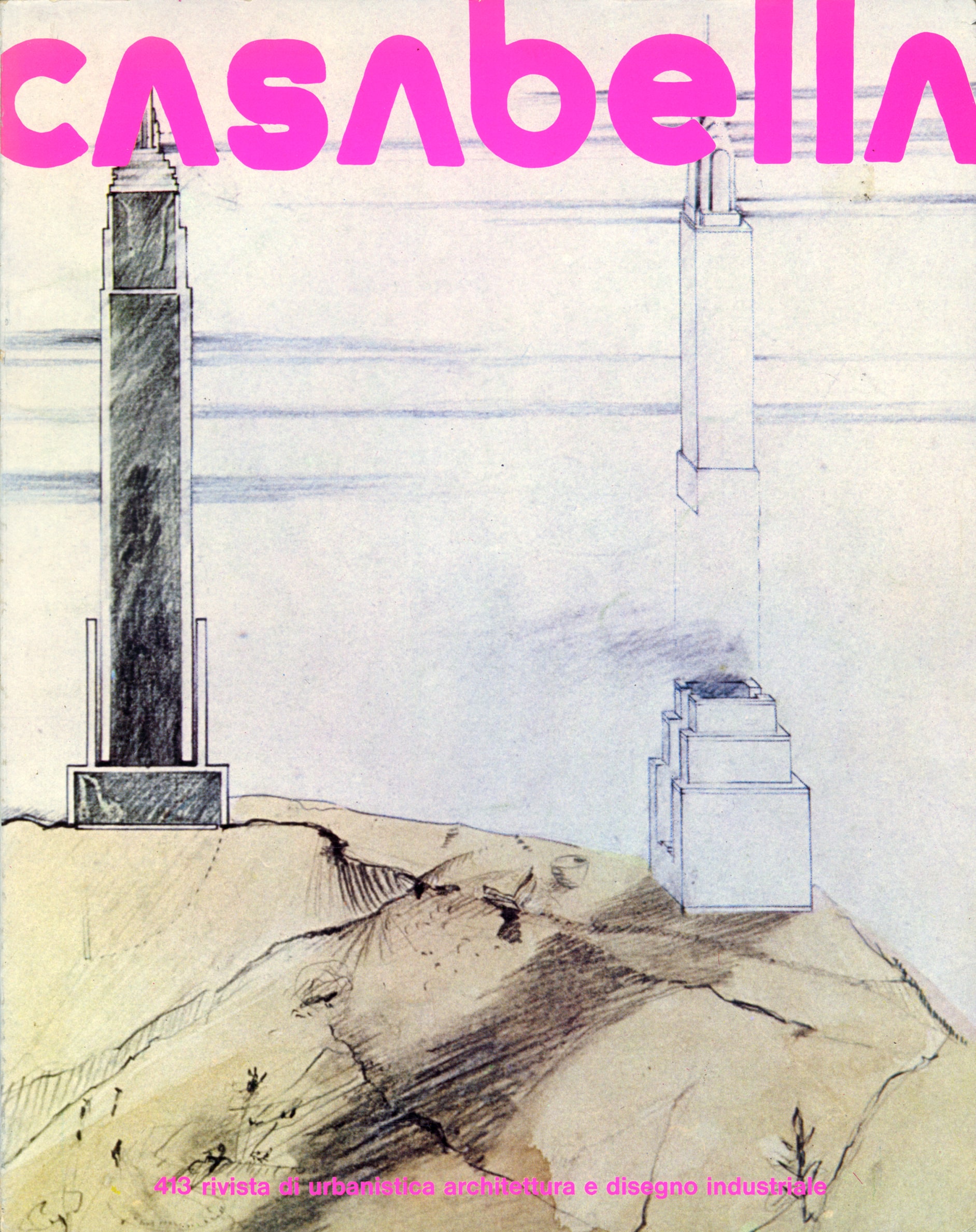

PW: Well, Dalibor was focused on surrealism then—there was a sort of surrealist revival in the 1970s. It was super interesting—also loads of Duchamp. At that time Elia and Rem Koolhaas had just produced their first joint project, Voluntary Prisoners of Architecture. We really liked the fact that it was published in Casabella, which was the vehicle of our greatest interest at the time—architettura radicale. Elia’s teaching assistant was Leon Krier. Alvin had just picked up Leon from the Stirling office.

MD: What was the relationship between Zenghelis and Krier at that time? What was it like working between them?

PW: They were both meant to be talking about the city, that was the common theme. What attracted us to Elia’s unit was that we thought Leon Krier was tongue-in-cheek. We presumed it was all irony and then to our dismay, realised it wasn’t. We then played up.

MD: What was the project that the tutors had set for you?

PW: I don’t think I actually did a project with Leon. Shortly afterwards I drew The Second London Fire project, which is now in the AA archive. It was a reaction to Leon’s Reconstruction of the European City thesis—a reconstruction of London after a devastating fire. But it was 100% provocation (Fig. 4).

MD: Was Koolhaas teaching with Zenghelis?

PW: No, he was writing Delirious in New York.

MD: What kinds of things were you reading at the time?

PW: I didn’t read much—Calvino, Borges, The Fountainhead, which was not yet politically incorrect. Nigel read everything. It was terrifying. He could quote anyone. Barthes was pouring out of him. Nigel and Bernard would have conversations in seminars while the rest of us just sat there looking at them.

MD: Was Nigel in the unit with you?

PW: No. Nigel and Jenny joined Bernard and Jeanne and I joined Elia. We basically divided at that point. Then, after the Diploma Committee decided against failing us and instead gave the four of us the Diploma Prize, Nigel and Jenny came back as teaching assistants to Bernard, and Jeanne and I as teaching assistants to Elia. We taught one year with Elia alone. It was quite exciting—Elia would come in in the morning and say ‘I was talking to Rem last night. I designed a Sphinx Hotel on the telephone’. He would report all these things that they were designing verbally. Then Rem returned.

MD: Last night during the exhibition opening at Betts Project you mentioned Superstudio. I was looking recently again at their ‘Twelve Cautionary Tales’ published in Architectural Design …

PW: Yes, we were aware of all of that.

MD: … and it struck me, seeing that once more, how alike the Voluntary Prisoners of Architecture project is. It just twists the narrative a little bit …

PW: Yes, exactly, Rem and Elia took Superstudio’s critique and made it propositionally positive, but still ironic. Because Rem’s book was out when he came back, he was hugely courted and published everywhere—nobody had ever done an architecture book which was so visually seductive. Jeanne and I thought, as we were teaching in the studio, that we’d have to Manhattanise. So we each made a model: mine the Empire State Building and hers the Chrysler Building. We screwed a suitcase handle on the side of each to make elongated picnic boxes—sandwiches in the base, bottle in the shaft. I’ve actually still got mine next door—it’s somewhat clumsily made, sawn on the kitchen table. This was our condescension to Elia and Rem, carrying around the Empire State Building on a London bus. At that time, we had discovered the Landmark Trust and used to go and stay in curious follies. A couple of times we rented the Gothic Temple at Stowe and that was a really important landscape experience. There are pictures of Jeanne and me with Empire State and Chrysler Building in hand, striding across the Elysian Fields (Figs. 5-7).

MD: That connects to something I want to ask about – the emblematic quality of particular kinds of architecture and the importance of that to you. I’m thinking about early projects such as the Bird House or the Water House—and in a way the Villa Auto as well—where there’s an intensely metaphorical character but also a very strong sense of the presence of the object within a broader landscape. I remember when we went together to look at the Bird House drawings in the V&A archive—I hadn’t realised until then that it was in East Anglia and it had to be understood in relation to the flatness of that landscape.

PW: Yes—it’s Suffolk, exactly where W.G. Sebald later walked in his Rings of Saturn. The Bird House is important as it was done a couple of weeks after graduating from the AA. One realised that everything one had done as a student was addressed to our teachers—we had father figures and wanted to shock them. On graduating from the AA the protective umbrella had been taken away and it was now necessary to invest in a serious work of architecture. That for me was the Bird House. It was obviously influenced by Raimund Abraham who used to regularly turn up at the AA. And while teaching with Elia, Tony Vidler was in London for half-a-year and associated with Elia’s unit. He was delivering his AA Ledoux / Boullée lecture series, The Writing of the Walls. We had really long seminars with him—it was incredible, a profound introduction to architecture parlante.

MD: Tony’s work on the ritualistic aspects of Enlightenment architecture – the initiation rites of the Lodges etc. that he was writing about—is wonderful. In the Bird House, where you find the wings left behind—or still to be donned—there’s a sense of a narrative sequence of transformation …

PW: … the Bird House wasn’t actually mapped in plan like that. It emerged in section …

MD: Yes, but in the section one still sees that through the structure of a sequence of stages—an understanding of some kind of journey of events that unfolds, as I recall anyway …

PW: Yes, and there was something vaguely performative about it. After our Diploma submission we had rented a house in Suffolk to relax and hang about. We all wandered off into the landscape. Jenny and Nigel found an abandoned house and made some pseudo-Cabbalistic signs on the wall and painted vectorial dashed lines across the floor and other space-articulating stuff. I found my windmill and did a more conventional version of what they were up to. But this idea of the body actually being there, of the physical experience of place, is what germinated in my work at that moment.

MD: It’s interesting—again, last night you mentioned Ledoux’s drawings, the sections I suppose, in relation to your own drawings. I hadn’t really made that connection. I’m always struck by the poché in those drawings—whether they’re by Ledoux or the more explicitly figurative drawings of Lequeu—by the specific quality of the hidden volumes of the architecture.

PW: Yes, that sense of depth in drawing on a page. What I was really taken by was when solid things were just left as white paper, and only the depth became distinguished, articulated by shade…

MD: Considering the sectional interest that is there in the Bird House, the Water House, and also the first Shinkenchiku Comfortable House—did the idea of the section hold a particular value for you in the way you were thinking about the development of the projects?

PW: I think I discovered it through those drawings actually. The whole sequence was a consequence of only teaching half a day a week. I had an enormous amount of time on my hands. As a student I had been taken up with being present at the AA, going to almost every lecture, and that was overwhelmingly immersive. Afterwards one was a little on one’s own. I used the house as a typological and emblematic template—each house had its character, its personality. Those drawings took an enormously long time as well—they were sort of crafted, sitting with a pencil, shading, shading, shading. It was meditative.

MD: You’ve talked about Bachelard before in relation to these.

PW: Bachelard we got from Dalibor—The Poetics of Space. Actually, my AA project about the fire of London was based on Bachelard’s Psychoanalysis of Fire.

MD: At what point does the specific thinking on the figurative enter? Is that something that was always present, or does it gradually emerge—through, for example, the identification of particular inhabitants of the houses whose characteristics and traits seep into the architecture, a bird-man with the Bird House, and so on?

PW: In the Bird House it was ‘bird’ because the windmill that I found had been populated by swans—big white feathers everywhere. When Jeanne and I stopped teaching with Elia and Rem we collaborated with Mike Gold and Paul Shepheard—the four of us taught a unit together. I think the figurative was a particular theme of Mike’s. He and I used to organise life classes in his flat in Notting Hill.

MD: Tell me about the group, The London Architectural Club, which you were involved in.

PW: That was a really interesting forum and particularly British. With Elia and Rem and Dalibor it was all very European, with theory as reference. The Club was the initiative of Paul Shepheard and Will Alsop, with their mentors James Gowan and Cedric Price commenting. We met at Paul’s house, somewhere in Camden, once a month or something like that. Most of us were young Turks at the AA. Also at that time, Peter Cook had given Jeanne and myself an exhibition at Art Net, his Covent Garden gallery—we were the exhibition following a show by the Smithsons called ‘A Tree’, ‘A Fence’, or something like that.

MD: These meetings were taking place around the mid-1970s?

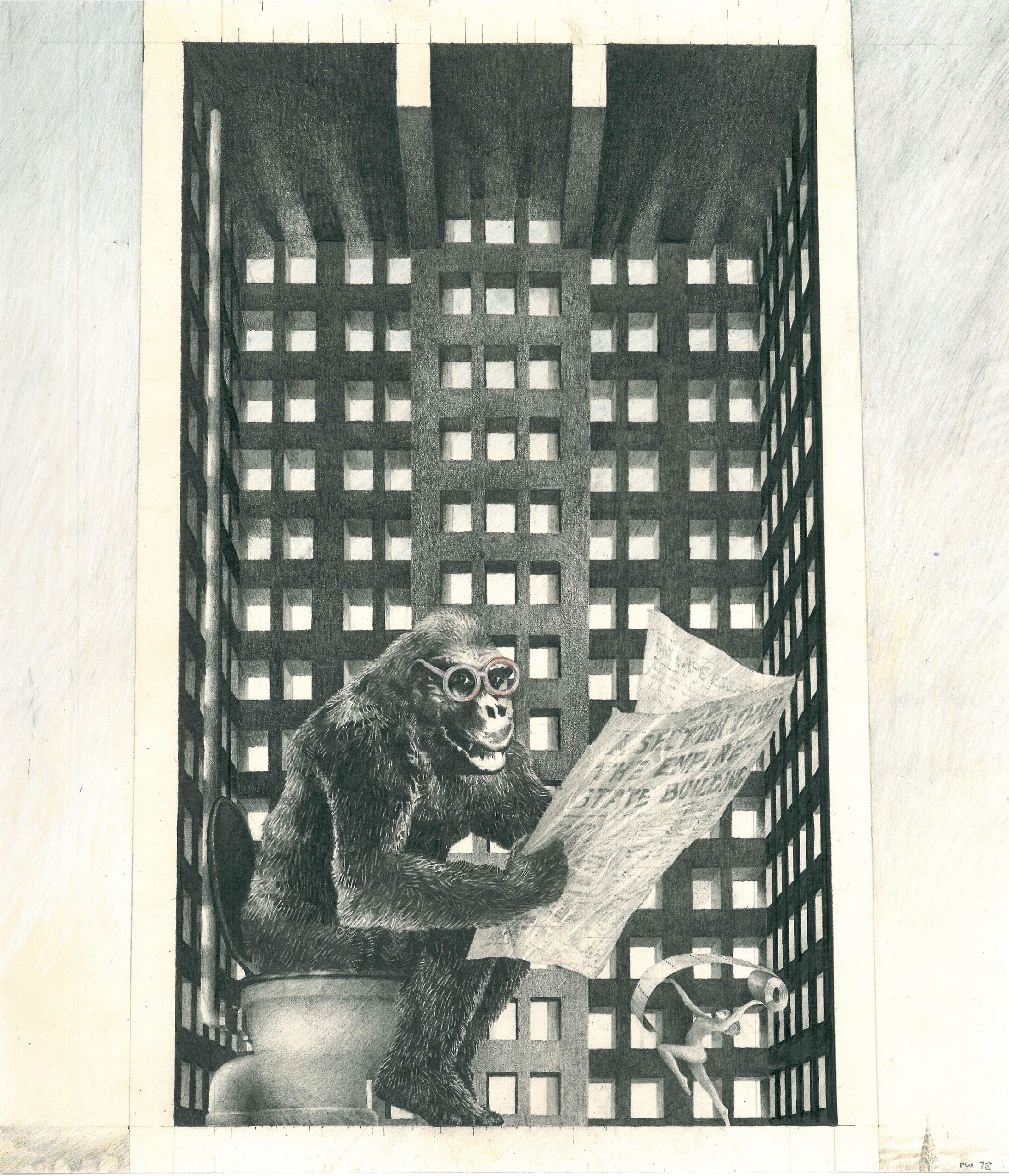

PW: This is 1975/76. Actually, when I started producing things like the Water House, the person who really helped was Leon Krier. He hadn’t taken offence, and put me in touch with Maurice Culot, and the Brussels ‘Reconstruction of the European City’ faction, who published me in Archives d’architecture moderne. From there, without my knowledge, Manfredo Tafuri took my 1977 Comfortable House and King Kong Inside the Empire State Building drawings and included them—alongside Madelon Vriesendorp’s 1975 Flagrant délit—in his book The Sphere and the Labyrinth, where they were used to illustrate his condemnation of ‘L’architecture dans le boudoir’ (Fig. 8).[2]

MD: And there is this interest—maybe it’s not so explicitly there in Krier, I suppose it flows through Dalibor again—in the remythologisation of the everyday. In the discussions at the London Architectural Club meetings, did Cedric respond or react to the work you were producing?

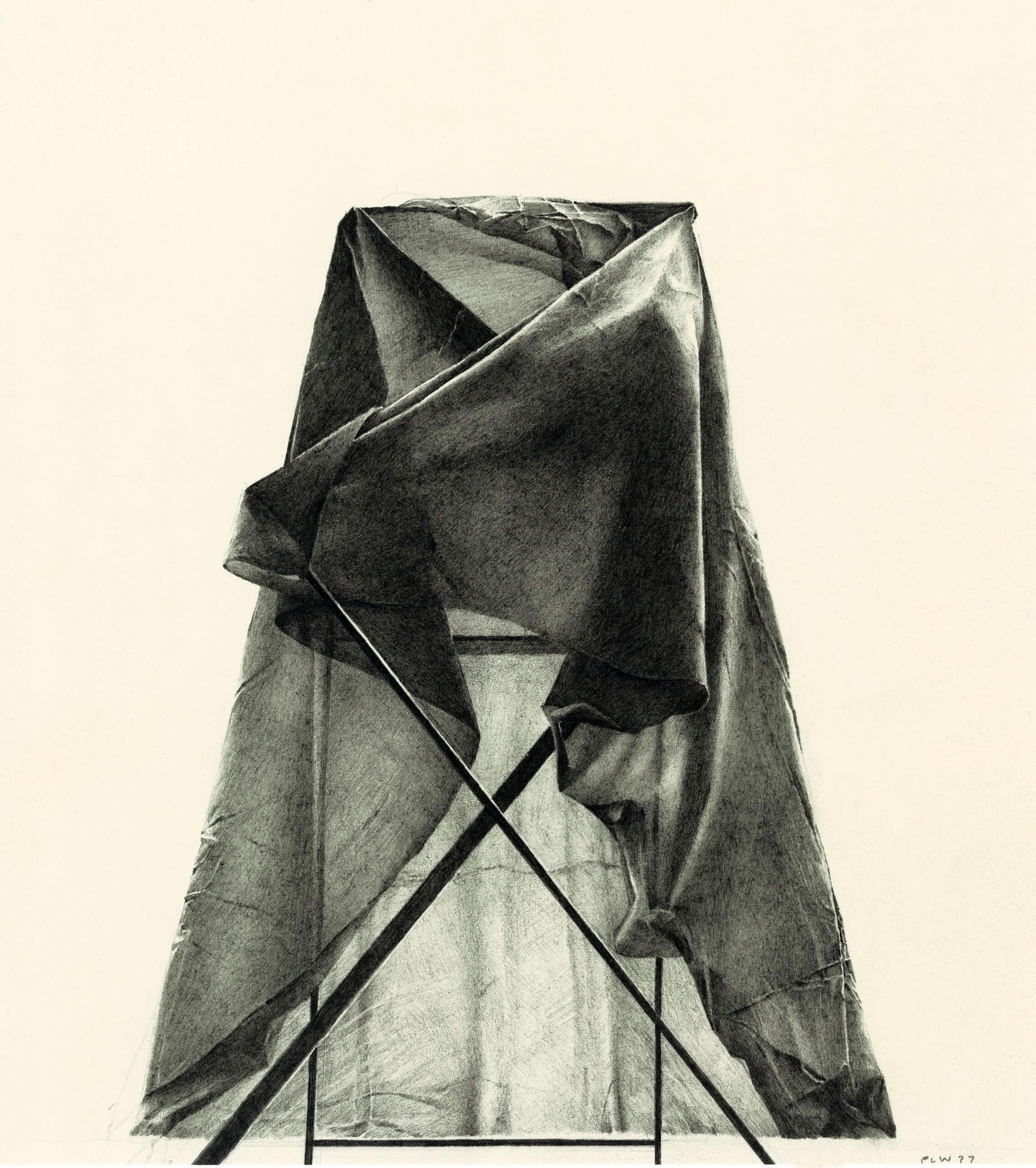

PW: Yes. I did one presentation—I’d just moved into the studio, and I wanted to put a curtain on the window so I’d made a construction of wood and draped some cloth across it. Then I did a drawing of its fabric folds and shadows. Cedric got really excited by that, I don’t understand exactly why because he wasn’t a graphic person. I think it was because it was sort of performative and provisional … it was something which hadn’t found its form (Fig. 9).

MD: I’m sure that’s right … an act of just draping this fabric, but then also looking closely at that, really examining what is purely contingent. I want to ask about the relation between figuration and abstraction, and the way that that gets negotiated—you can see this playing out in the work in various ways, and one of the ways it gets articulated is through the ‘frame’ and ‘adjacency’ idea.

PW: That dialectic was a post-rationalisation …

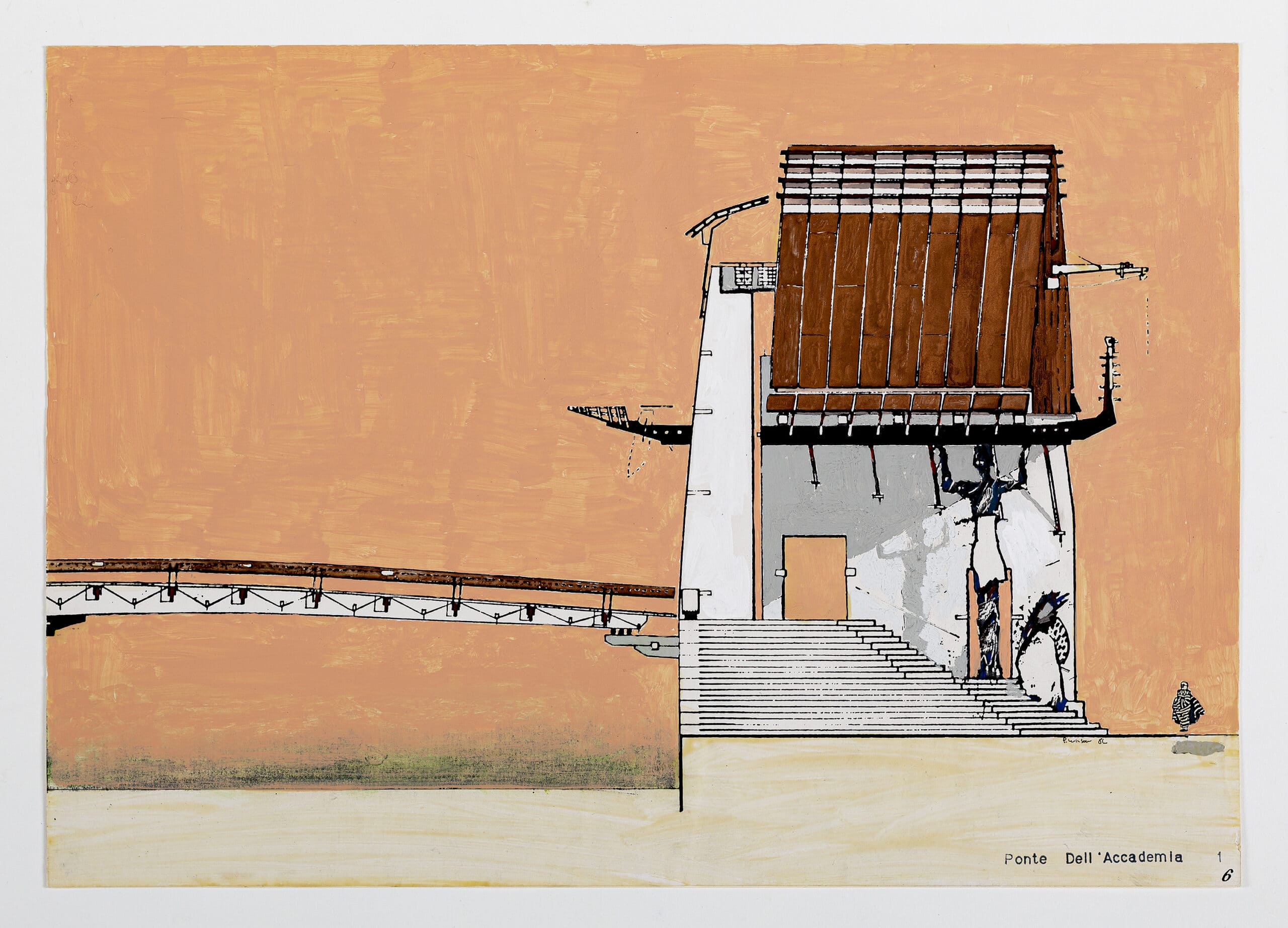

MD: Last night, whenever you were talking about Tony Vidler’s seminars and Ledoux, I was thinking about Lequeu then as well, and the drawings of the cow shed figured as an idol, a sacred cult object—a kind of literal and intense architectural figuration, which in a way re-appears with the cultic objects of Pop. But then on the other hand, there is the pure geometry of something like Ledoux’s spherical rural caretakers’ house, which also works within the parameters of the idea of an architecture that ‘speaks’, that articulates itself. And, it seemed to me, thinking about this, that another way we could talk about the relation between figuration and abstraction in your work is through the occupation of a kind of middle position between these extremes, or maybe an oscillation between them. In the Accademia Bridge, for example, or the Pont des Arts, there is a very legible figural presence produced by the elements, but one that at the same time doesn’t pass beyond a certain limit—other than on some occasions, such as the Egyptian ‘boat of the dead’ gondola carrier in the Accademia project (Fig. 10) …

PW: Yes, that’s very direct … I think that drift into remythologisation was something that was happening at the time. The Italian Radicals had mutated into Global Tools and Natalini was doing things like collecting walking sticks, seeing small everyday objects as things of significance.

MD: To what extent is the specific way the projects are imagined as being drawn or projected part of their conceptual framework and a way of orientating their architectural—spatial and material—qualities? As you move from those early houses into the bridgebuilding and shipshape period I have an increasing sense of those architectures being dynamically projected from particular visual positions. Perspective starts to become more important …

PW: I, at the time, made my AA students construct a perspective from the plan up—really laborious. They worked a whole term on one big piece of paper—it was reminiscent of the ‘tracing room’ floor at Wells Cathedral, with sideways projections here and there, sections slipped out on train tracks. Basically, I think the Foucauldian prison of perspective was for us a really brilliant format for learning to think spatially. On the other hand, there’s one of my drawings called Opera at Sea – Adjacencies Overboard. I was aware at one point of accumulating all this figurative baggage, it just became too much. You wrote about that.

MD: With the earlier house drawings, the visual position feels very stable. The architecture seems implanted and static—even if it’s about air and flight, as in the Bird House. But by the time we get to the Bridgebuilding projects and the Clandeboye work, the drawings …

PW: … start becoming filigree …

MD: … mobile, provisional, contingent …

PW: That was also the time for moving away from the massive materiality of Rational buildings, for example, and into Memphis’s frivolous forms. I was always considered by Nigel and Jenny and the others as being dangerously close to Rationalism, because I had drawn the Water House—absolutely square. Rationalism was a parallel discourse at the time. There was an extreme polarity between that stringent mode and the AA, which considered itself to be outside the European canon. I think it’s the canonical that doesn’t go down well with Anglo-Saxon empiricism.

MD: Were the kind of drawings that came out of the Austrian context—Raimund Abraham, Friedrich St Florian, Walter Pichler—important for you?

PW: Pichler was really important for me—I really admired Pichler’s drawings. I still don’t know how he did it—painted with tea or coffee or something.

MD: Yes, I’ve never felt I’ve quite grasped the relation in Pichler’s work between, on one hand, the enthusiasm with technology and inflatable structures and the television helmet and then, on the other, the more …

PW: … morbid …

MD: … sacral, earthbound work.

PW: There was a really good connection between Alvin’s AA and the Austrians. Alvin brought them in regularly—Hans Hollein as well.

Notes

- ‘Living the Modern_Australian Architecture’ was held at the German Centre of Architecture DAZ, Berlin between 12 September and 11 November 2007. Peter Wilson’s essay for the catalogue is republished as ‘Lifestyle Modernism’, in Julia B Bolles-Wilson and Peter L Wilson, Bolles + Wilson: A Handful of Productive Paradigms (Münster: Bolles + Wilson, 2009), 74–77.

- The drawing, as it is reproduced here, has been cropped by Peter Wilson, so that spaces in the interior of the Empire State building above and below Kong have been removed. The more expansive rendering of the New York skyline in the original image has been reduced, leaving only the top of the Chrysler Building visible (on the lower right of the drawing) and some shadowy forms (on the lower left). It was the earlier state of the drawing that appeared in The Sphere and the Labyrinth—under the title The Enigma of Cultural Appropriation and dated 1977. For the drawing’s initial outing in Archives d’architecture moderne, Wilson had given the title as Cultural Appropriation. However, on publication this turned out to have been rendered as L’énigme de l’appropriation culturelle, and hence the title in the Tafuri book (email correspondence with Peter Wilson, 16 May 2021).

Mark Dorrian is Editor-in-Chief of Drawing Matter Journal, holds the Forbes Chair in Architecture at the University of Edinburgh, and is Co-Director of the practice Metis. His work spans topics in architecture and urbanism, art history and theory, and media studies. Dorrian’s books include Writing On The Image: Architecture, the City and the Politics of Representation (2015), and the co-edited volume Seeing From Above: The Aerial View in Visual Culture (2013).

Peter Wilson is a founding partner in Architekturebüro BOLLES+WILSON. Peter is the author of Some Reasons for Traveling to Italy (2016), Some Reasons for Traveling to Albania (2019) and Bedtime Stories for Architects (2023). His drawings are held in the collections of Drawing Matter, V+A, CCA, DAM Frankfurt. BOLLES+WILSON are the subject of three El Croquis Monographs and the publication, A Handful of Productive Paradigms (2009).

This article first appeared in The Journal of Architecture, 26:5, Architectural Lineaments: Adventures Through the Work of Peter Wilson, ed. Mark Dorrian (2021): 599–638.

– Mark Dorrian and Peter Wilson