Gilles-Marie Oppenord

For French architects, the Grand Prix (later the Prix de Rome) was not formalized until 1720; however, study in the Italian peninsula was considered a crucial stage of an aspiring architect’s education. Gilles-Marie Oppenord, son of a cabinet-maker to Louis XIV, travelled to Rome in 1692 under the patronage of Edouard Colbert, marquis de Villacerf, the king’s head of buildings works at the royal palaces. Through his skills as a draftsman, he quickly gained the favour of Matthieu de La Teulière, director of the French Academy in Rome. As Joseph Connors has outlined, La Teulière’s correspondence while Oppenord was in Italy between 1692 and 1699 is filled with his appreciation of the young architect’s abilities on paper. La Teulière personally encouraged Oppenord in this capacity, assigning him the task of verifying Antoine Desgodetz’s influential measurements of ancient buildings and suggesting him as a draftsman to the French ambassador, Cardinal de Bouillon. It is likely that Oppenord also consulted La Teulière’s extensive collection of works on paper that the director had gathered at the Palazzo Mancini for French architects to study while in Rome. So vast was the number of Oppenord’s drawings by the time he left Rome that La Teuilère questioned how he could possibly bring them all back to Paris. [1]

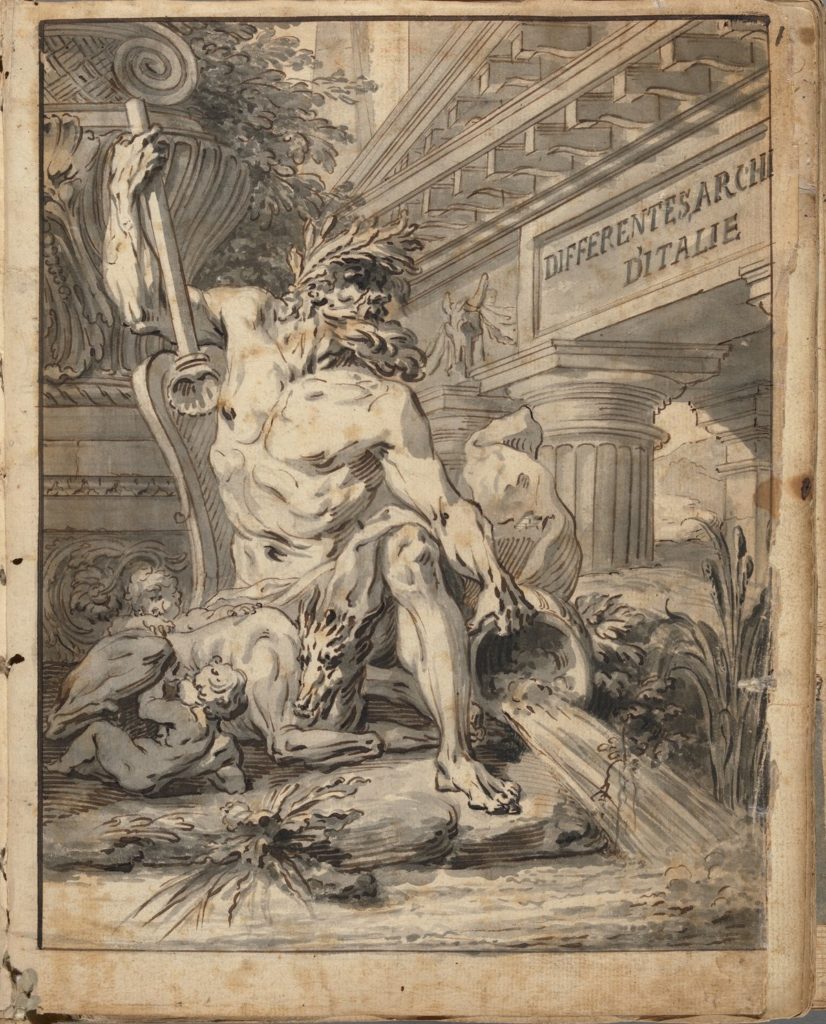

Among these, were sketchbooks that probably existed first as small leaflets of only six or eight sheets that Oppenord later had bound. Six sketchbooks are known today, arguably the most spectacular of which is in Harvard’s Houghton Library, which was recently included in the exhibition and catalogue organised by Ewa Lajer-Burcharth and Elizabeth M. Rudy, Drawing: The Invention of a Modern Medium (January 21 – May 7, 2017, Harvard Art Museums). The sketchbook retains its original binding, which reads in Oppenord’s own hand: ‘Recueil de plusieurs morceaux d’architecture des différents maistres italiens. L’an M.DC.IIC [1698]. Oppenord’. [2]

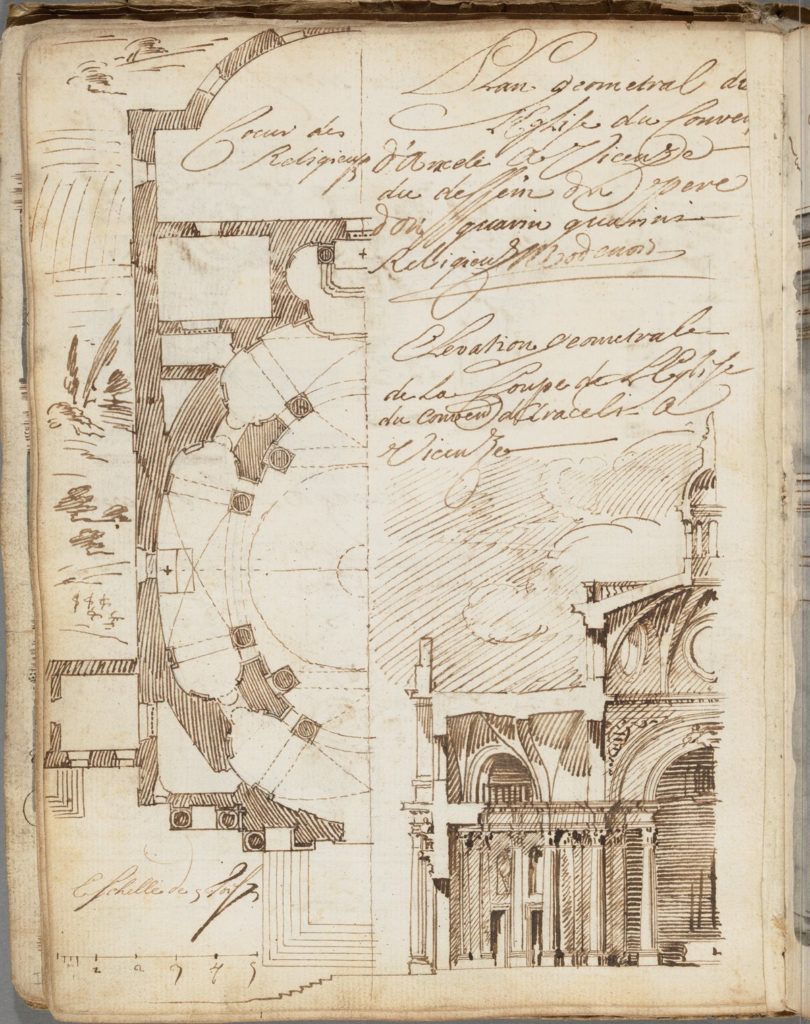

On its spine, the number 107 indicates the sketchbook’s place in a large group of reference materials. Its pages document buildings by Palladio, Michelangelo, Borromini, and others throughout Rome, Tuscany, and the Veneto. Villacerf believed Oppenord could study Palladio’s buildings satisfactorily through the plates in the architect’s treatise I quattro libri dell’architettura (1570); however, with La Teulière’s support, Oppenord successfully petitioned to visit a host of architecturally-rich cities, including Vicenza, Padua, and Bologna between June 9 and November 11, 1698. The Houghton sketchbook’s high degree of finish, alternating between pen and ink or washes over graphite, and its detailed annotations (often exceeding in specificity and formality anything Oppenord would need for personal use) suggest that it may have been meant to be published or presented to his patrons, if not as a gift then as reassurance of a decision well made.

While playful, picturesque vegetation and sculpture abound, the sketchbook records a tremendous quantity of precise information. Oppenord provided a concordance of measurements used in France and different regions of Italy, and noted that several of these were specific to architects and not daily use. He employed conventional forms of architectural representation that not only demonstrated his own facility in trade-specific vocabulary but also presumed an audience able to read its signs. These include an economic reproduction of only half of symmetrical designs, including his alternate views of a convent from Vicenza; use of sections, plans, and elevations; and a system of lettered references linking image and text. Beyond his audacious handling of pen and brush, Oppenord’s developing sense of authorship is announced throughout the album, even as he reproduced others’ buildings. His signature appears three times (possibly corresponding to earlier, individual leaflets) and to his own designs he has annotated ‘mon Invention’, ‘Oppenord Invenit’, and finally, the title ‘Epitaffe de moy [sic] gravé sur marbre’ above a full-page escutcheon. [3]

In Paris, Oppenord became official architect to the king’s nephew, the duc d’Orléans, but his fame was secured through Huquier’s largely posthumous publication of his drawings. When Oppenord died in 1742, Huquier purchased the majority of his collection, proceeding to cull drawings for individual motifs and combine them freely in print, a procedure that was consistent with his treatment of drawings by Watteau and Boucher. [4] A small section of his oeuvre devoted to Oppenord, the four-part Livre de fragments d’architectures, recüeilis et dessinés à Rome d’après les plus beaux monuments (1742–48), also known as the ‘Petit Oppenord’, takes its frontispiece directly from Oppenord’s ‘Epitaffe de moy’ and includes many motifs pulled from the Houghton album, albeit stripped of their identifying annotations. The economic condensation of a range of motifs and information follows from Oppenord’s original, but the visual éclat of dramatically juxtaposed scales, rhythmically aligned profiles, and the witty inclusion of figural sculpture amidst geometric forms has been lost.

As Katie Scott argues in her book The Rococo Interior (1996), when circulated in print Oppenord’s drawings for ornament provided especially rich fodder for critics of the rococo (then known as the ‘nouveau goût’ or ‘style moderne’), who established a historiographic tradition that placed Oppenord as the conduit—or culprit—connecting baroque Rome and rococo Paris. [5] As it had been for La Teulière, Oppenord’s seductive facility on paper proved crucial. In his Vies des fameux architectes (1787), Antoine-Nicolas Dezallier d’Argenville summarised this peculiar curse of Oppenord’s talented draftsmanship: ‘Oppenord drew the figure like a painter, and ornament to the greatest perfection. His drawings in pen and ink are highly esteemed: they alone made his great reputation. Their bold, seductive touch prevented anyone from perceiving that they would not retain the same effect in execution’. Their inevitable destiny was, however, among ‘amateurs of bizarre and contorted forms, those that plunged France into Barbary’. [6]

This text is adapted from David Pullins, ‘Architecture & Design’ in Drawing: The Invention of a Modern Medium, Ewa Lajer-Burcharth and Elizabeth M. Rudy eds. (Cambridge, MA: Harvard Art Museums, 2017).

Notes

1. Joseph Connors, ‘Borromini in Oppenord’s’, in Ars natural adiuvans: Festschrift für Matthias Winner, ed. Victoria V. Flemming and Sebastian Schütze (Mainz am Rein, Germany: P. von Zabern, 1996).

2. ‘Receuil of several pieces of architecture by different Italian masters. The year M.DC.IIC [1698]’. See ibid., 609–10; and Elaine Evans Dee, ‘The Oppenord Sketchbook’, in Design into Art: Drawings for Architecture and Ornament: The Lodewijk Houthakker Collection, vol. 1, ed. Peter Fuhring (London: P. Wilson, 1989), 79–81. The other five sketchbooks are in the Louvre (RF 35698); Nationalmuseum, Stockholm (NMH THC 5106-5125); Kunstbibliothek, Berlin (Hdz. 2405=OZ90); Cooper Hewitt Museum, New York (1960.102); and Canadian Centre for Architecture, Montreal (DR1996:0013).

3. ‘My epitaph carved in marble’. See pages 2 (verso), 36 (verso), 59 (recto), 67 (recto), 76 (recto), 74 (verso), and 78 (recto).

4. See ‘Albums and Sketchbooks’, in this catalogue; Jean-Francois Bédard, Decorative Games: Ornament, Rhetoric, and Noble Culture in the Work of Gilles-Marie Oppenord (1672–1742) (Newark: University of Delaware Press, 2011); Katie Scott, ‘Reproduction and Reputation’, in Rethinking Boucher, ed. Melissa Hyde and Mark Ledbury (Los Angeles: Getty Research Institute, 2006), 91–132; and Martin Eidelberg, ‘Gabriel Huquier: ‘Friend or Foe of Watteau?’ The Print Collector’s Newsletter 15 (5) (1984): 157–64.

5. Katie Scott, The Rococo Interior: Decoration and Social Spaces in Early Eighteenth-Century Paris (New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press, 1996), 261. Fiske Kimball frames Oppenord this way in The Creation of the Rococo (Philadelphia: Philadelphia Museum of Art, 1943), 91–93.

6. Antoine-Nicolas Dezallier d’Argenville, Vies des fameux architectes depuis la renaissance des arts, avec la description de leurs ouvrages, vol. 1 (Paris: Debure l’aîné, 1787), 438–39.

– Niall Hobhouse and Nicholas Olsberg