Ink on his Hands: Montano’s Visceral Roman Architectures

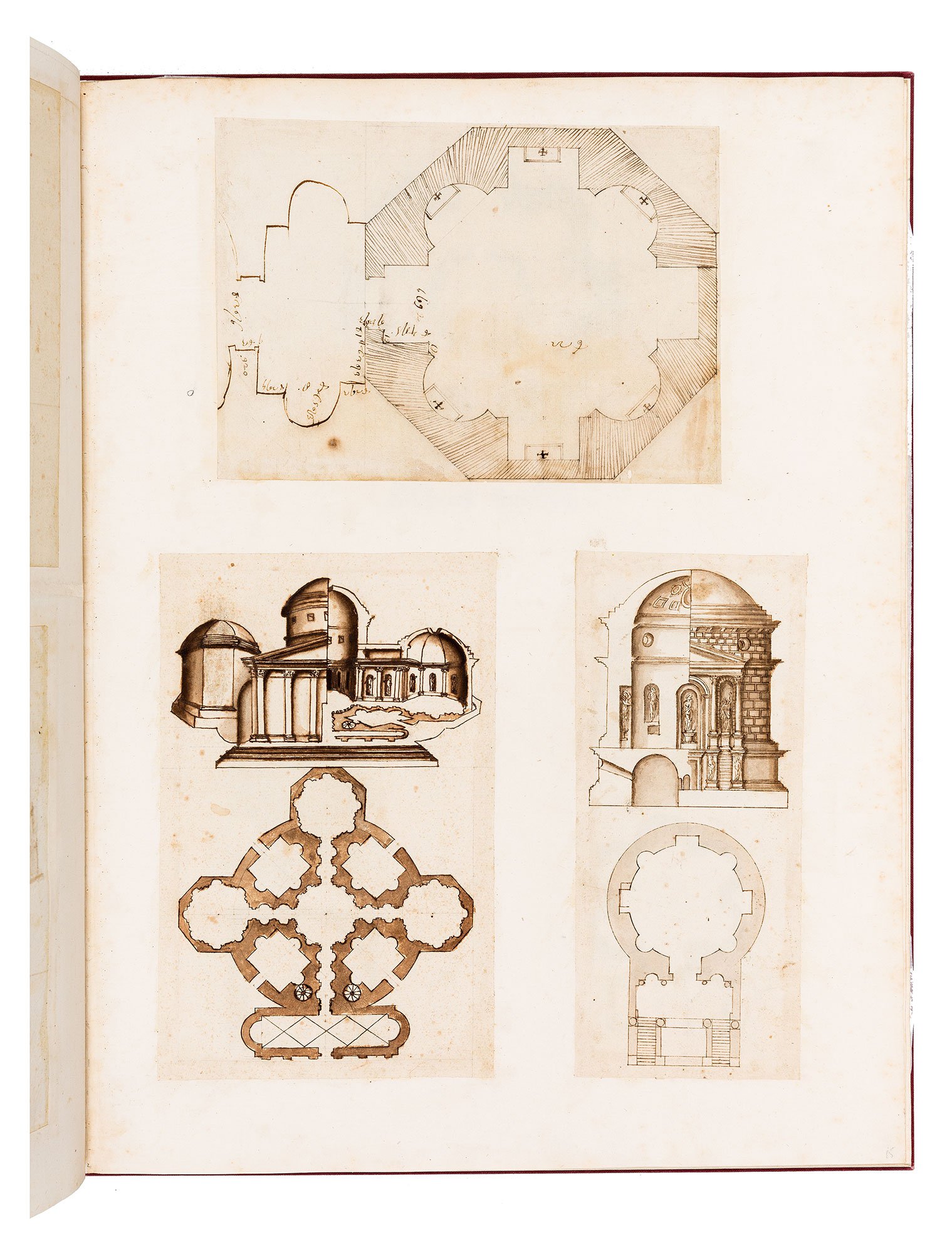

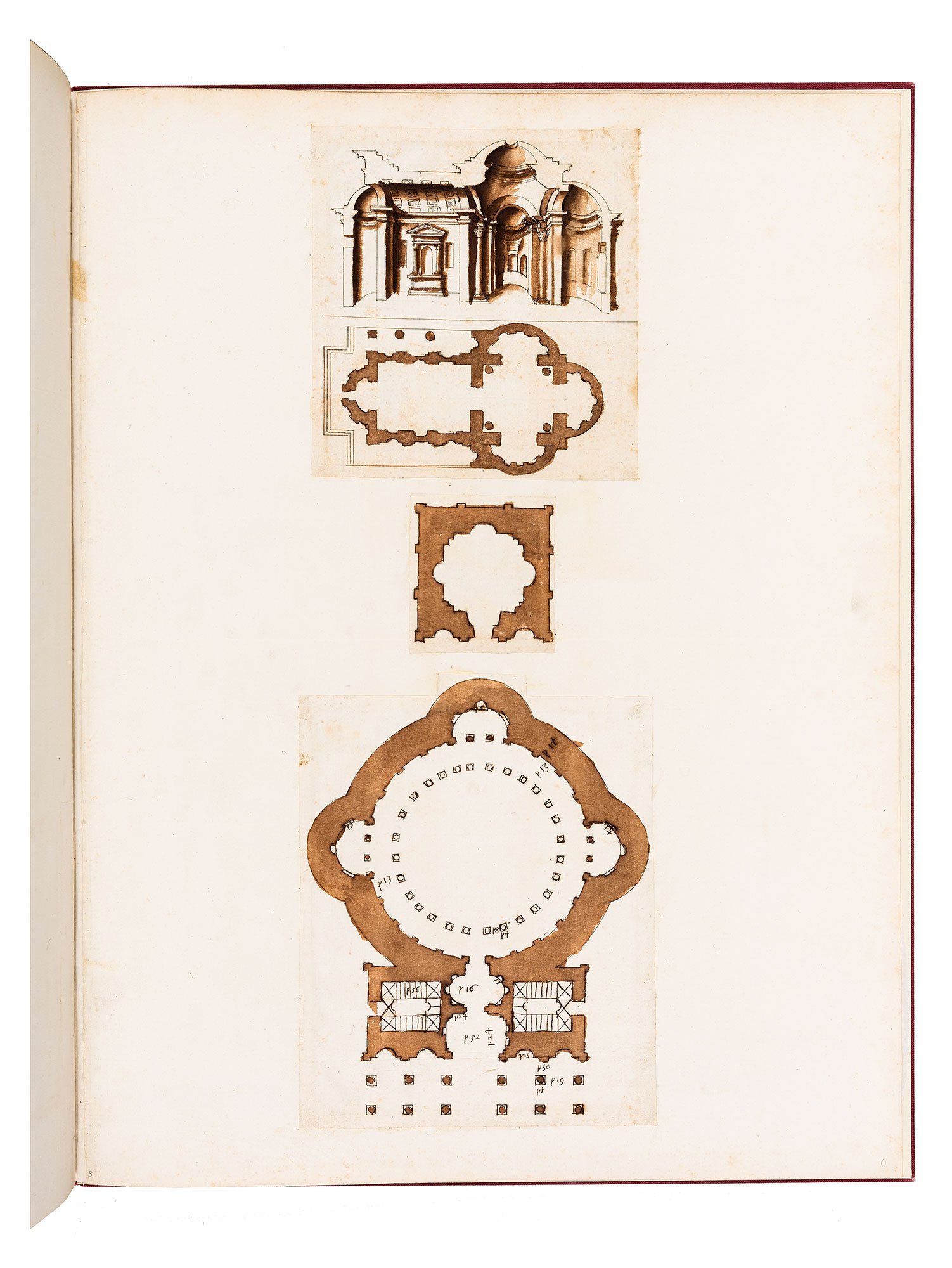

When he sat down to make the drawings that form this eight-page album of Roman buildings, Giovanni Battista Montano began by embossing lines onto the sheet with a stylus, straightedge and compass. Using natural black chalk, he then lightly sketched the principal parts and main particularities of the selected edifices. Next, Montano picked up his hand-cut goose quill and outlined the building’s lineamenti in iron gall or soot ink. He finished by colouring with brush and wash in freehand. The stylus underdrawings resourcefully positioned and delineated the edifices. The scarce traces of black chalk are most visible in areas without ink. In contrast to these first two layers, Montano’s ink gestures are conspicuous, agile, and confident. Frequently transgressing the ink outlines, his brush strokes impart a quickness of motion and an affective sense of dynamism. The wash intensifies the feeling of depth as Montano builds up layers in his fusions of sections and elevations, plunging the viewer into the edifices’ cavernous depths. But by the time he made these sheets, Montano was an expert draughtsman. The album was once a part of Cassiano dal Pozzo’s early seventeenth-century Museo Cartaceo, which for a time held at least 360 sheets of Montano’s drawings now distributed across Europe in London, Paris, Milan and Madrid. Most of these drawings used similar methods to depict the same buildings. And, in most cases, the drawings are not facsimiles. They are instead unique drawings, created by the architect as if for the first time, with their own chalk sketches, ink outlines, and wash strokes.

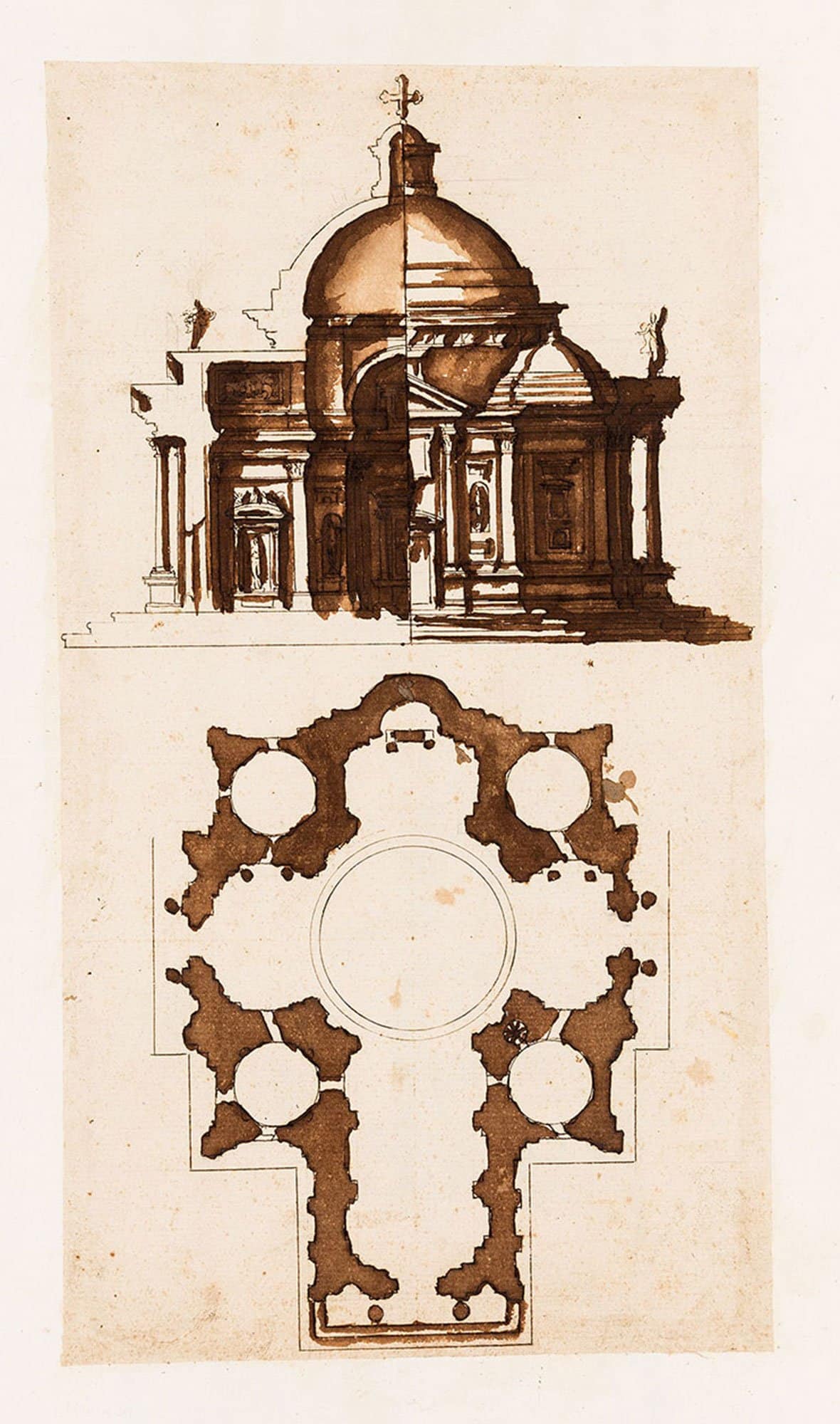

Montano’s Somerset drawings are small enough for four to fit on one album sheet. Each page depicts the elements of a building in plan, section, and (oblique) elevation, and often Montano combines the views in one all-embracing hybrid representation to simultaneously reveal and conceal. The approach is almost visceral as Montano partially peels away a facade to show the heart of the structure, demonstrating that even a small sheet of paper can intimately portray Rome’s most inner recesses. Despite their skillful execution, the representations reveal a spontaneity in Montano’s process, suggesting that the drawings were not didactic.

Apart from a couple of cruciform buildings, the majority of the album focuses on buildings with centralised plans. Montano was a member of both the Accademia di San Luca and the Virtuosi al Pantheon, which were founded to reflect on ancient Roman edifices and spolia, and to theologically centre and empower the artists of Rome. He would have been attuned to the tradition of hylomorphic solutions ensconced by Alberti, in which form and appearance hinged on significance and purpose. The centralised plan held a particular power and included mausolea, nymphaea, thermae and tempiettos, but also early baptisteria and churches. It was connected to water and rituals of spiritual purification. In short, centralised plans came to represent both the taming of the unruly natural spirits springing from Nature’s internal viscera and a harnessing of the naturally grotesque and monstrous through the presence and the sanction of the Holy Spirit.

The architectural expression of such divine presence can be seen throughout the Somerset album. For example, Montano draws an unidentified Roman structure with four domes over four grotto chambers to articulate an edifice that is profoundly devout. The apportioned plan (above, left) is constructed over circle guidelines that radiate from the centre towards the periphery of the structure, implying an elaborate backdrop to the scalloped interior walls. In turn, the narrow inner corridors and rooms are depicted in intense rhythmic self-reliant strokes that portray them as places of acute shadows and seclusion. Closely looking at the narrow corridors, or even to the main central chamber, reveals lace-like walls drawn in small, repetitive, segmented strokes. For instance, Montano almost always drew the semi-circles with two strokes, working from the outside toward the inside-middle of the half circle. Light was scarce inside this structure as its only inlet would have been the domes’ oculi. Was this building a sanctuary? A family mausoleum? Or maybe it is the ancient brick temple near Palestrina, as suggested by Sallustio Peruzzi and on an anonymous mid-cinquecento drawing at the Canadian Centre for Architecture. The answer remains unclear, but Montano unravels an intricate internal world that commands a feeling of reverence.

Similarly perplexing is another sheet of a circular building with an ambulatory and three apses shown only in plan. Coloured over barely visible underdrawings, the three-apse-rotunda plan appears to have been painted in just four brush strokes. Montano did not colour the central columns, and he depicted the apses and the niches as hollow, allowing the inner space to subtly materialise. Taken as a whole, the rendering suggests the building embodied a sombre and commemorative atmosphere, perhaps not unlike that of the Pantheon. The edifice has been compared to Milan’s San Lorenzo but is also reminiscent of the period’s renderings of the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem (a more complex version of this can be found in Bernardino Amico’s 1596 Trattato delle piante e imagini di sacri edifizi). Montano’s rotunda is also represented in the CCA’s anonymous album. Peculiarly, even though the two plans have the same annotations, their proportions are greatly at odds.

While Montano is distinguishable by the ease of his brushwork, curatorially his choices seem to have followed well established Cinquecento convictions. The plans discussed turn up in Sallustio Peruzzi’s sheet of mixed sketches at the Uffizi in Florence; in an anonymous French artist’s album in Devonshire; on Pirro Ligorio’s folios in Naples; in Sebastiano Serlio’s 1540 Il terzo libro de le antiquita di Roma; in the so-called Codex Orsini in the Vatican; and in the folios of an anonymous sketchbook at the CCA. What is of greater importance, however, is that in Montano’s renderings, representational exactitude and originality are of no consequence. Precision is irrelevant. These drawings imagined Rome’s relics. Given the type of personified architectures and the artist’s unwavering execution, what surfaces as significant is Montano’s role as a performer, presumably even vendor, of astonishing representations that participated in a large network-like corpus – a genuine all’antica cornucopia – dispersed across the Italian peninsula and Europe.