Sourcing Superstudio

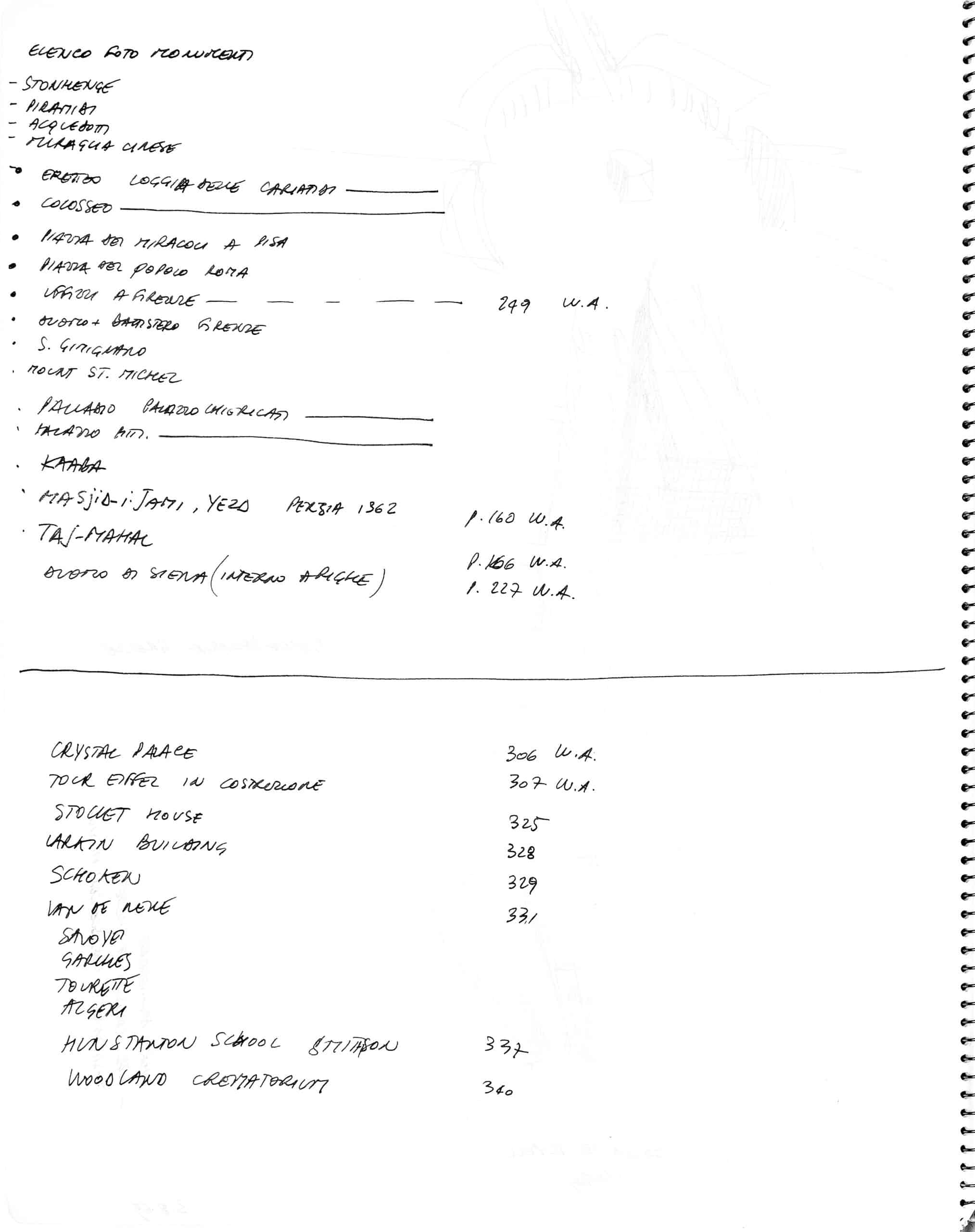

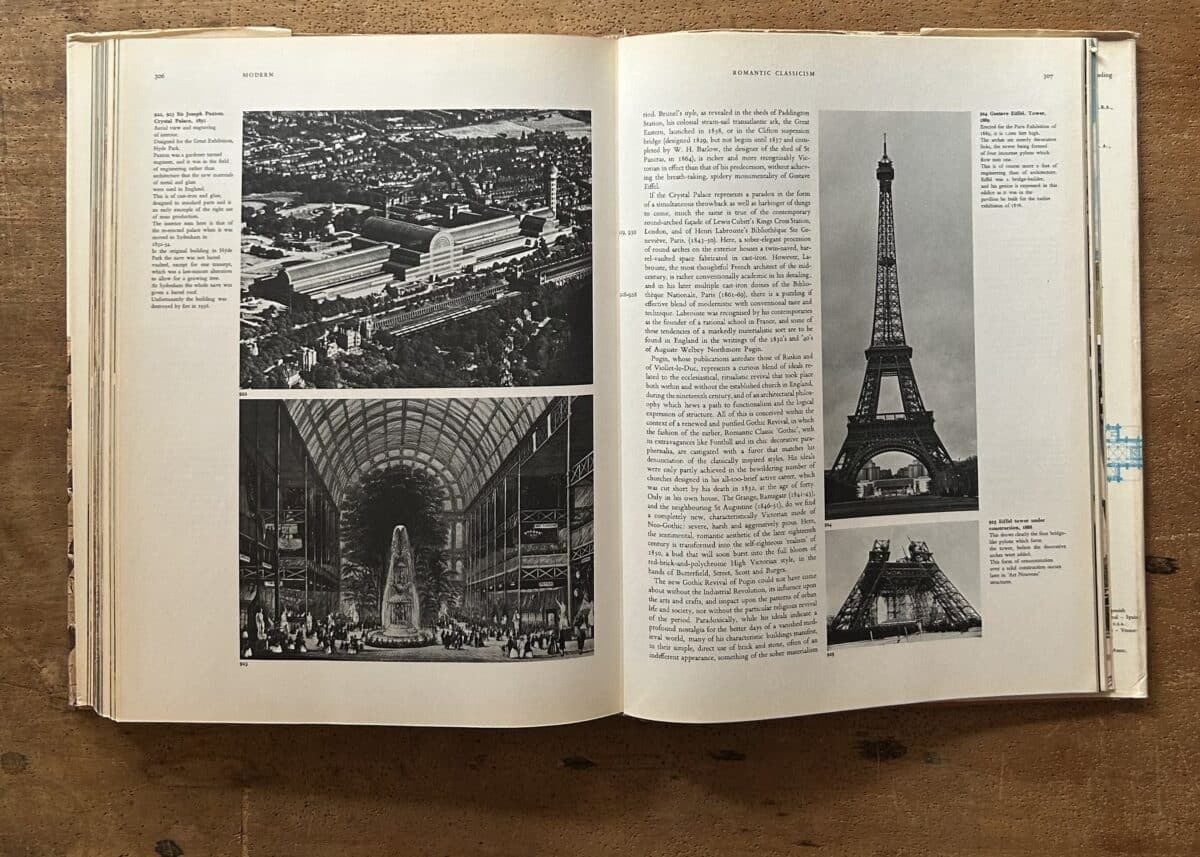

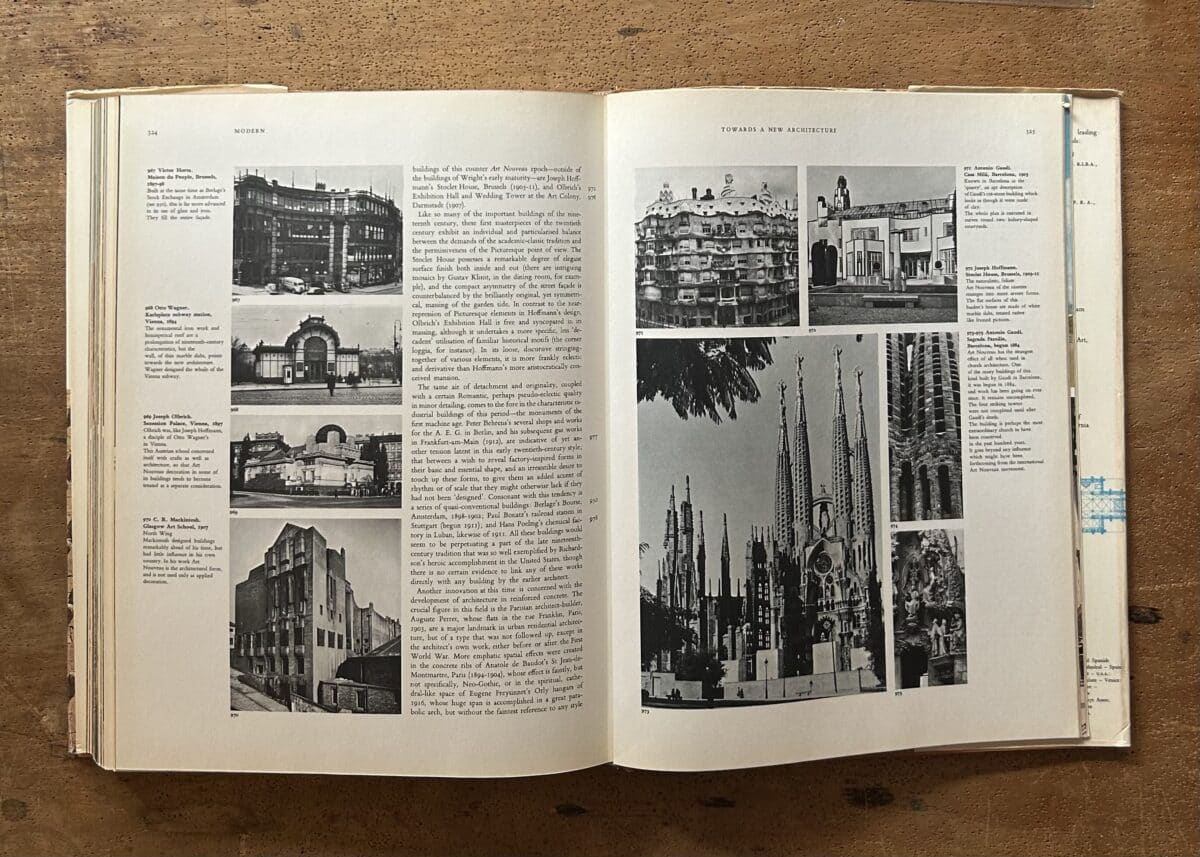

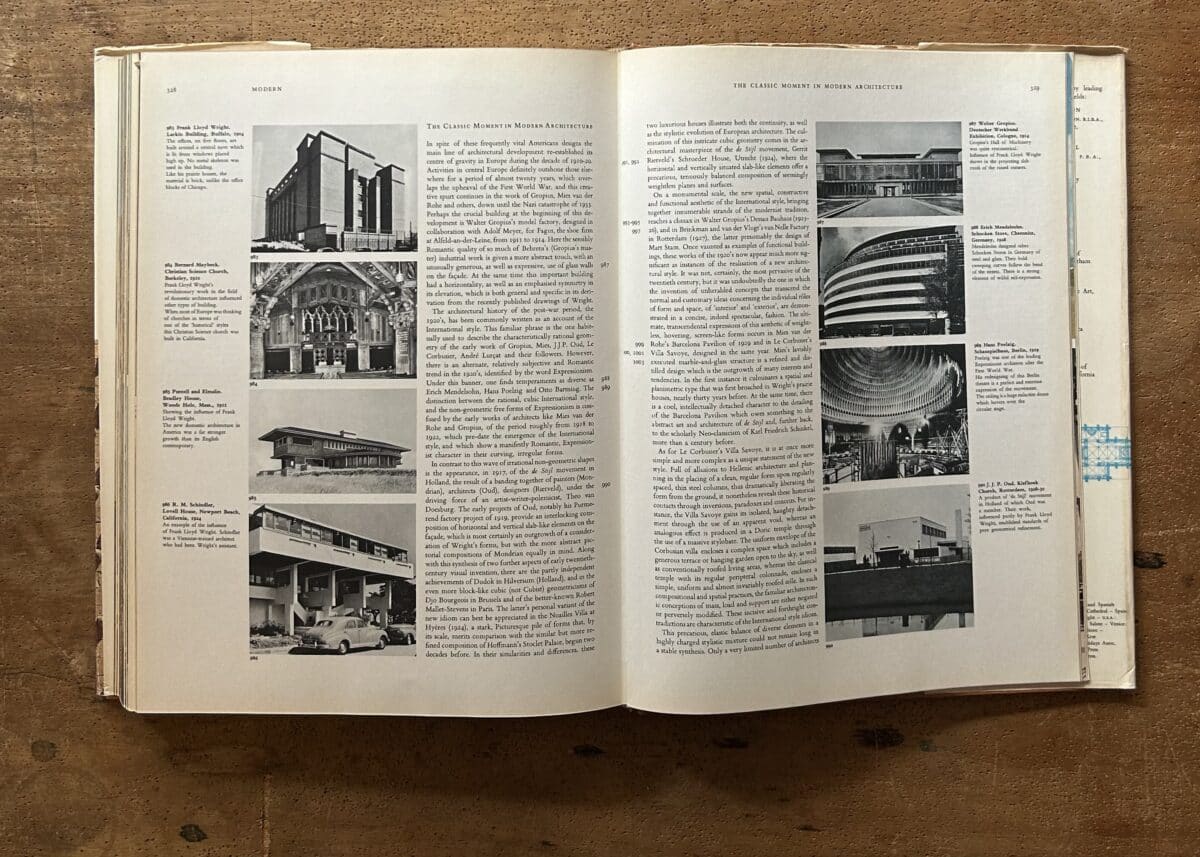

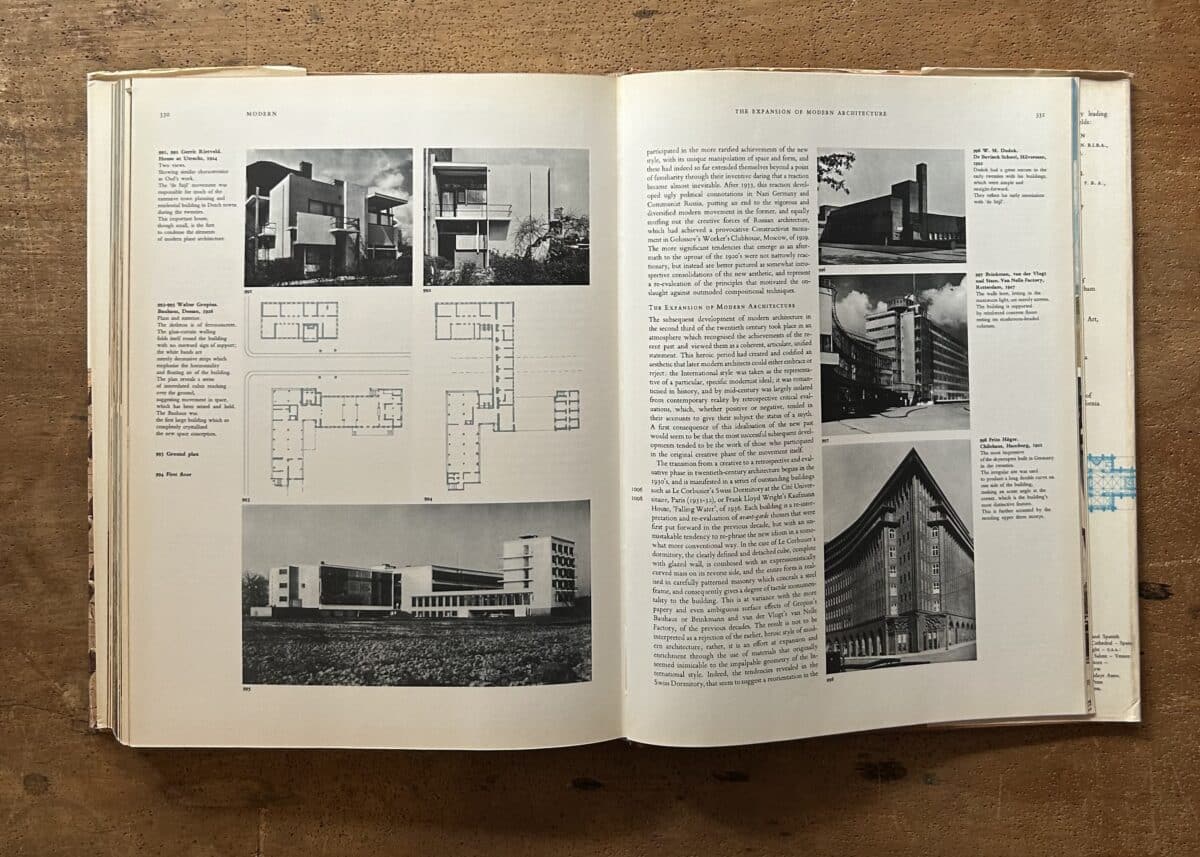

On the 21st page of Natalini’s 12th sketchbook (DMC 2141) there is a list of buildings and landmarks. It feels quite disparate at first. It begins as a chronological list of architecture’s greatest and most recognisable hits: Stonehenge… the Colosseum… the Uffizi… the Taj Mahal… Crystal Palace… the Eiffel Tower. Then it becomes a litany of famous projects from the twentieth century: Le Corbusier’s Villas Savoye and Garches, La Tourette, Algiers; Asplund’s Woodland Crematorium; the Smithsons’ Hunstanton School… A number often follows the names of these buildings, and sometimes the letters ‘W.A.’.

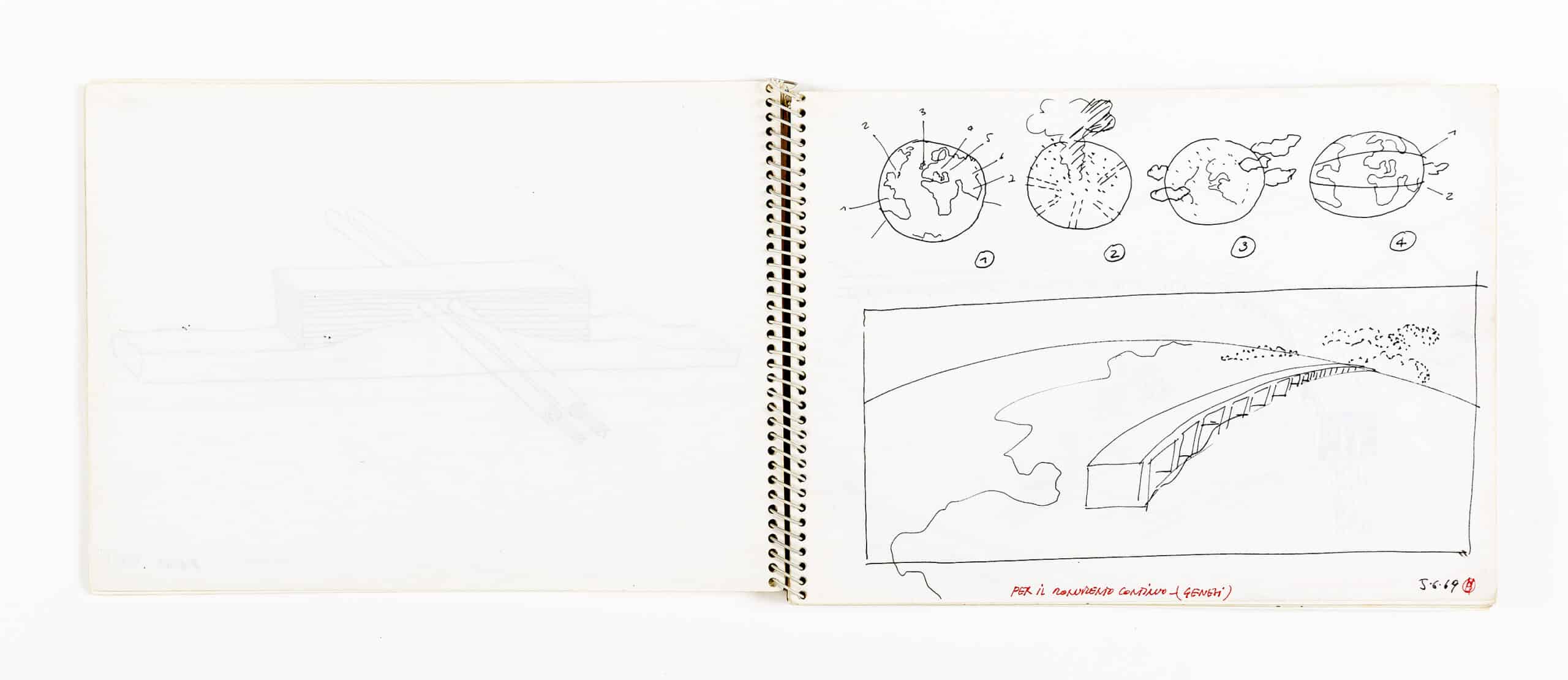

This sketchbook contains preparatory work for Superstudio’s 1969 Continuous Monument collages. The Continuous Monument—a white gridded superstructure that would make its way around the globe, eventually covering it—was a theoretical proposition: it was only ever going to exist on the page. The ‘radical’ power of the project would hinge upon its public representation and, in order to translate their abstract and provocative proposition of total urbanisation into a digestible narrative form, Superstudio drew on popular forms of illustration—films, and photomontages made of magazine scraps.

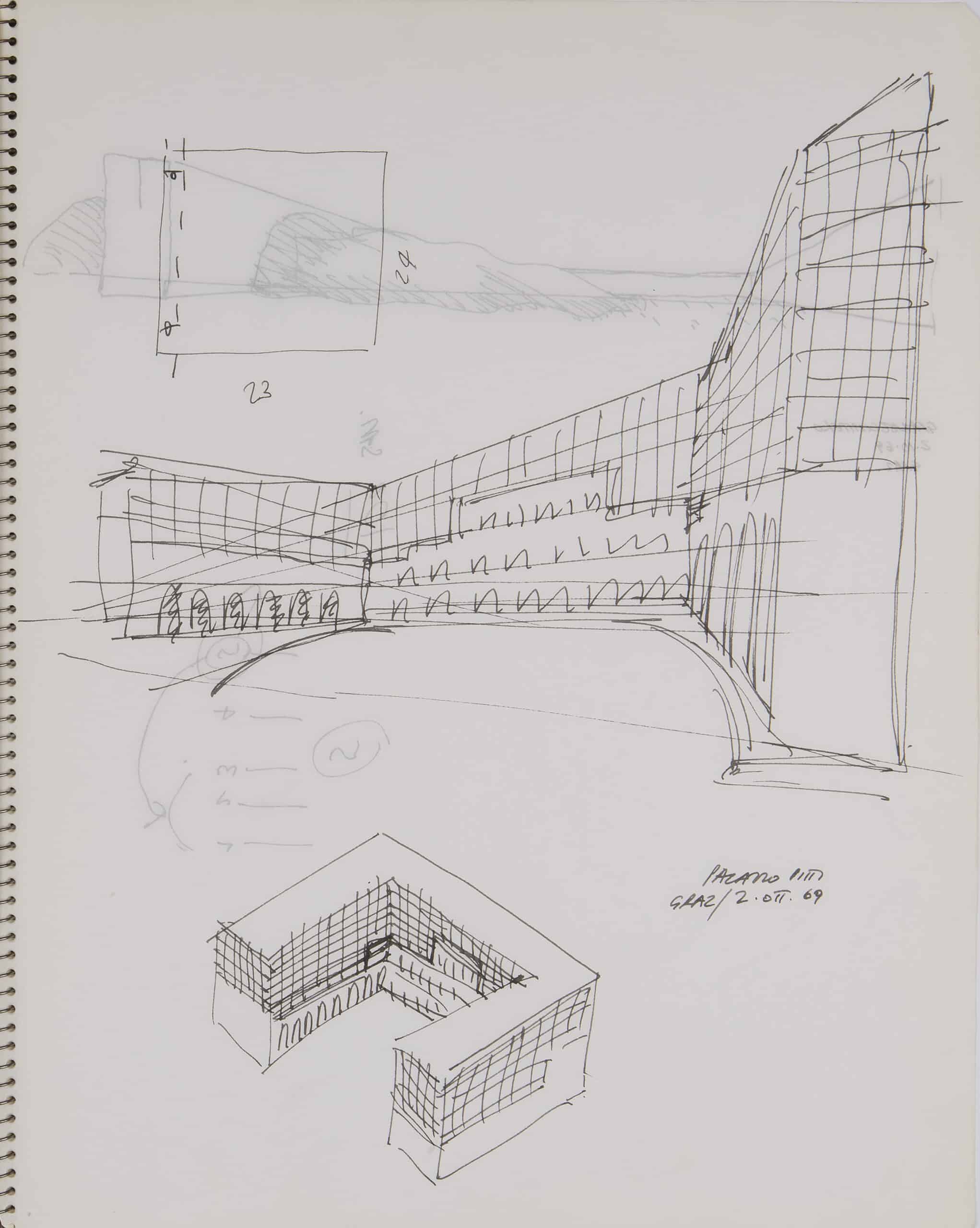

The Continuous Monument would have to be represented in space. But what space? Flicking through earlier sketchbooks, you can see the development. It starts life stretching into blank infinity, just curling itself round the edge of the globe. Then it moves through open space, empty space. Soon it moves through landscapes: deserts, mountains… It passes alongside a motorway and through downtown Manhattan. Only then does it start to interact with existing buildings.

So we return to the list on page 21. It’s one of the many lists in Natalini’s sketchbooks: events to attend, articles to read, guest lists… This list, it became evident, was a list of potential Continuous Monument locations: places through which it might pass. We decided the numbers were likely to be page numbers and that ‘W.A.’ could stand for the name of a book.

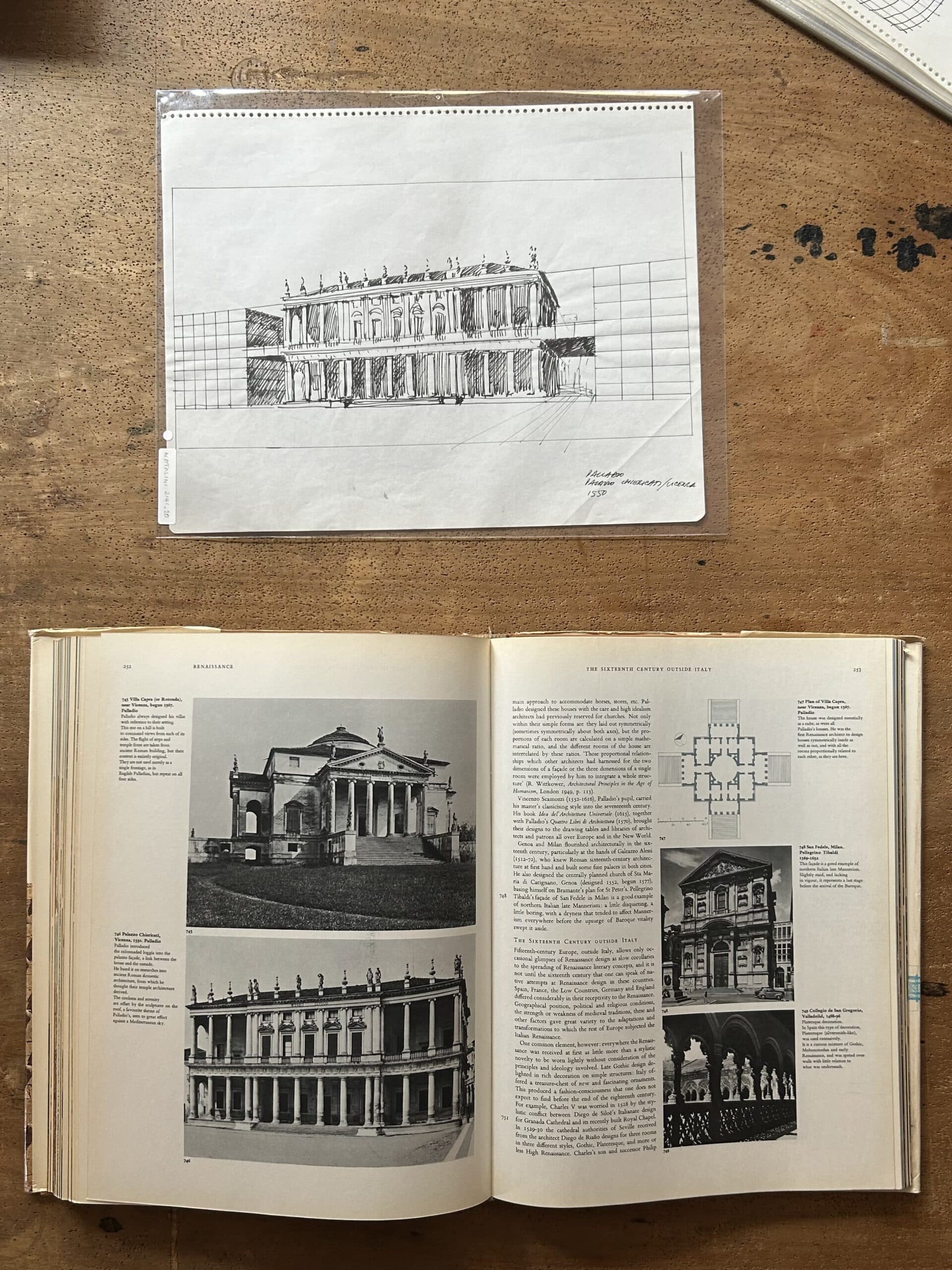

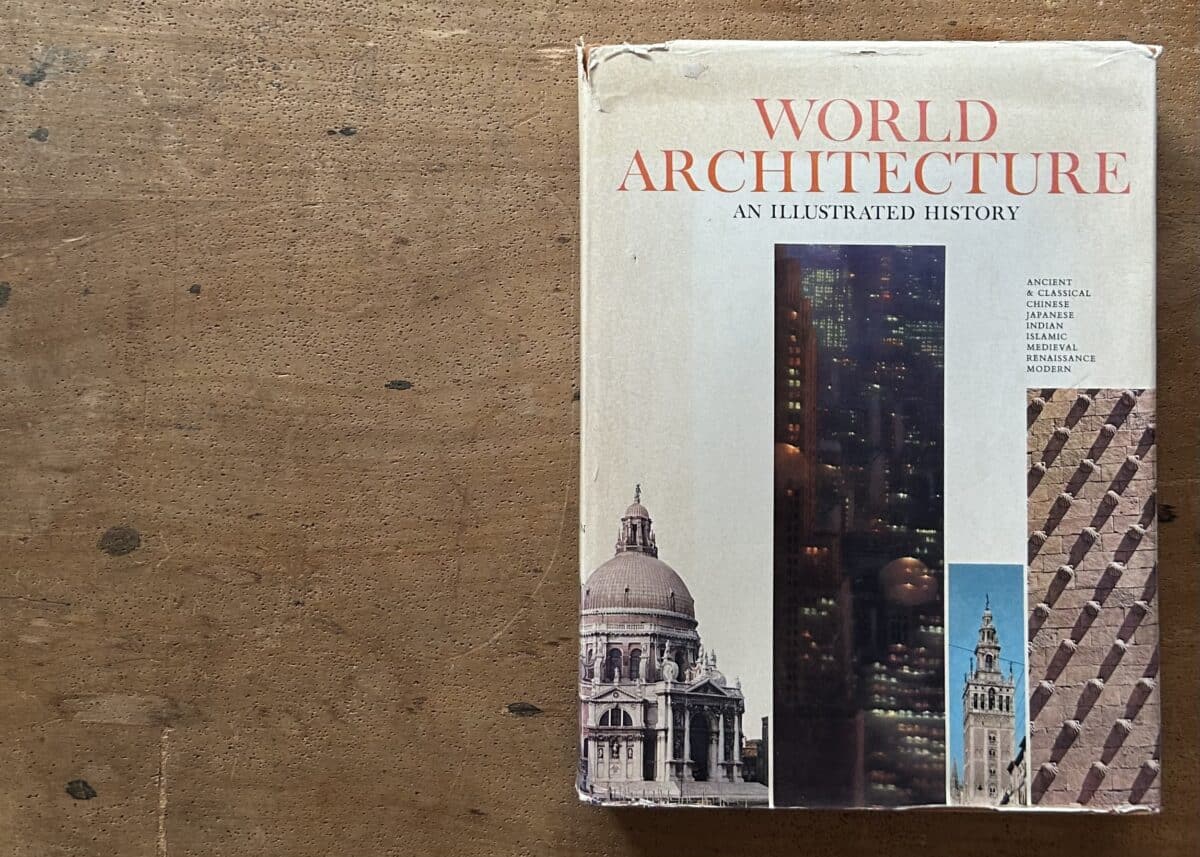

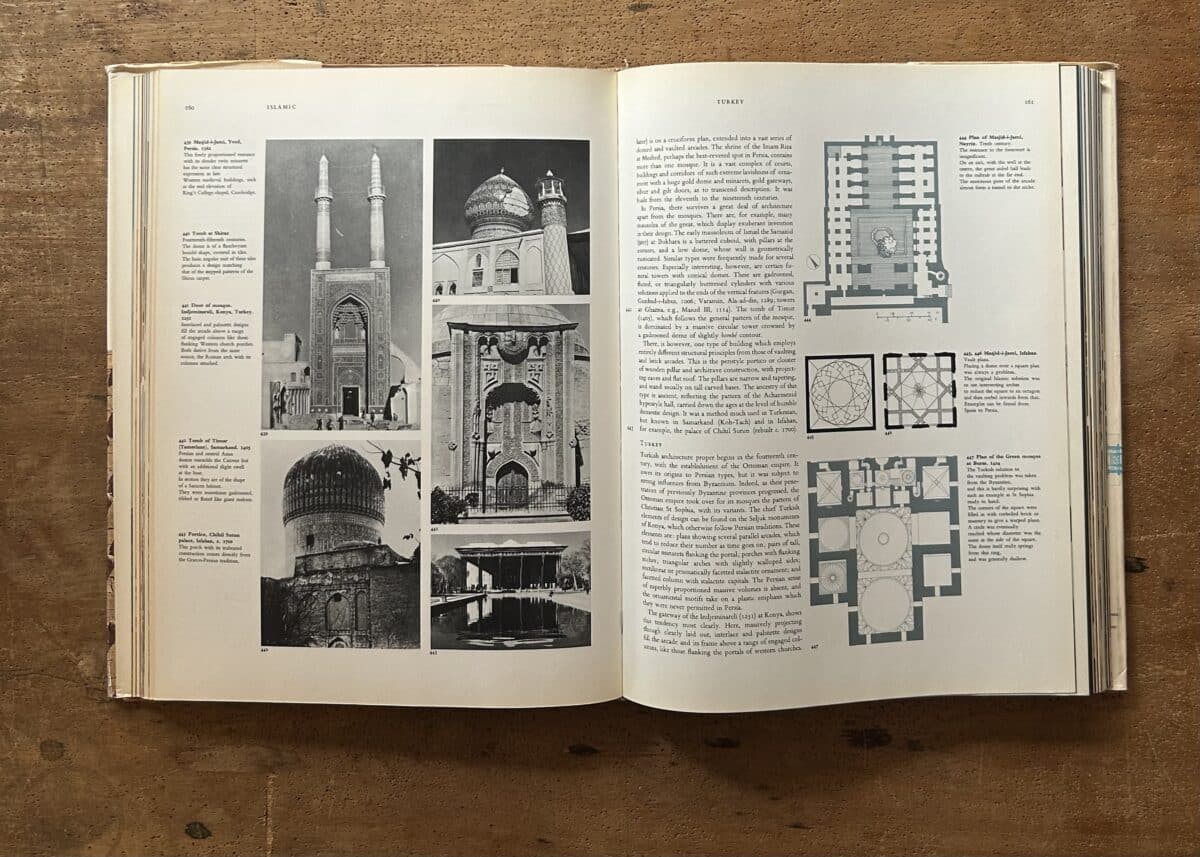

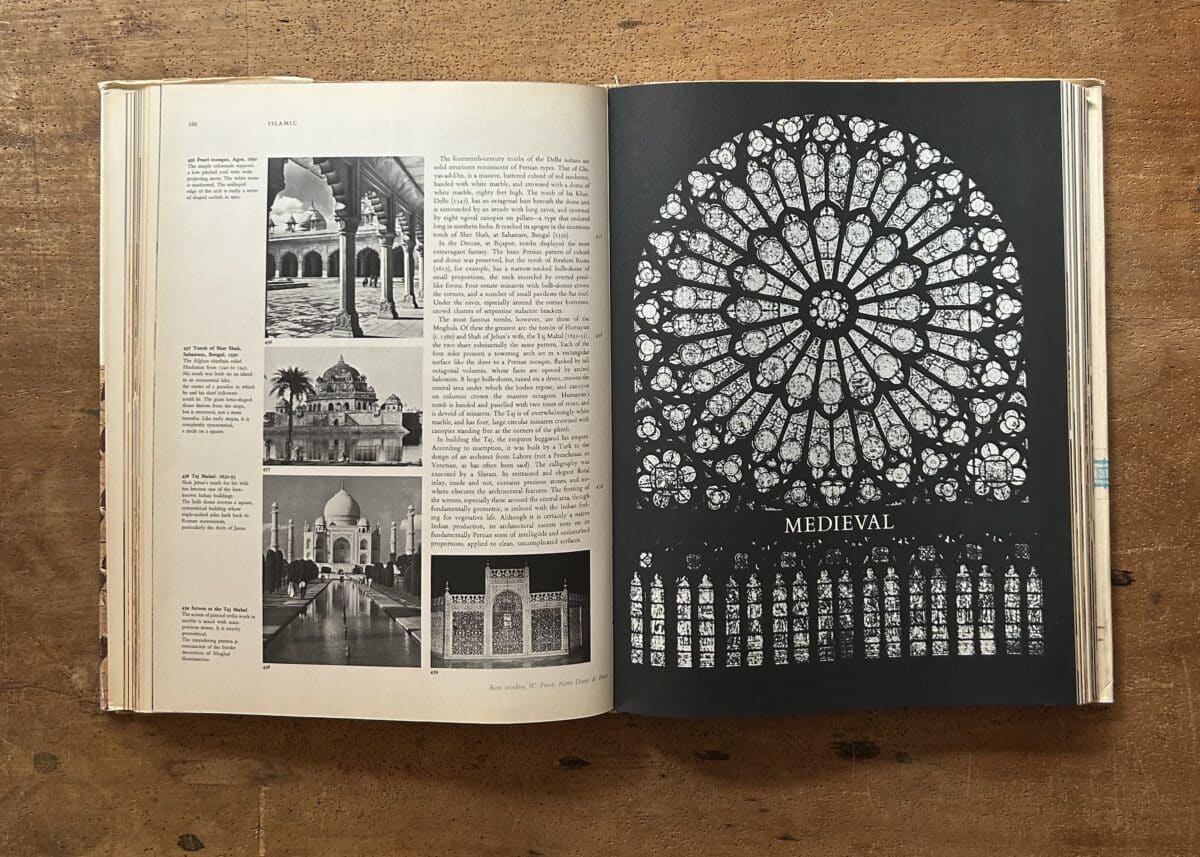

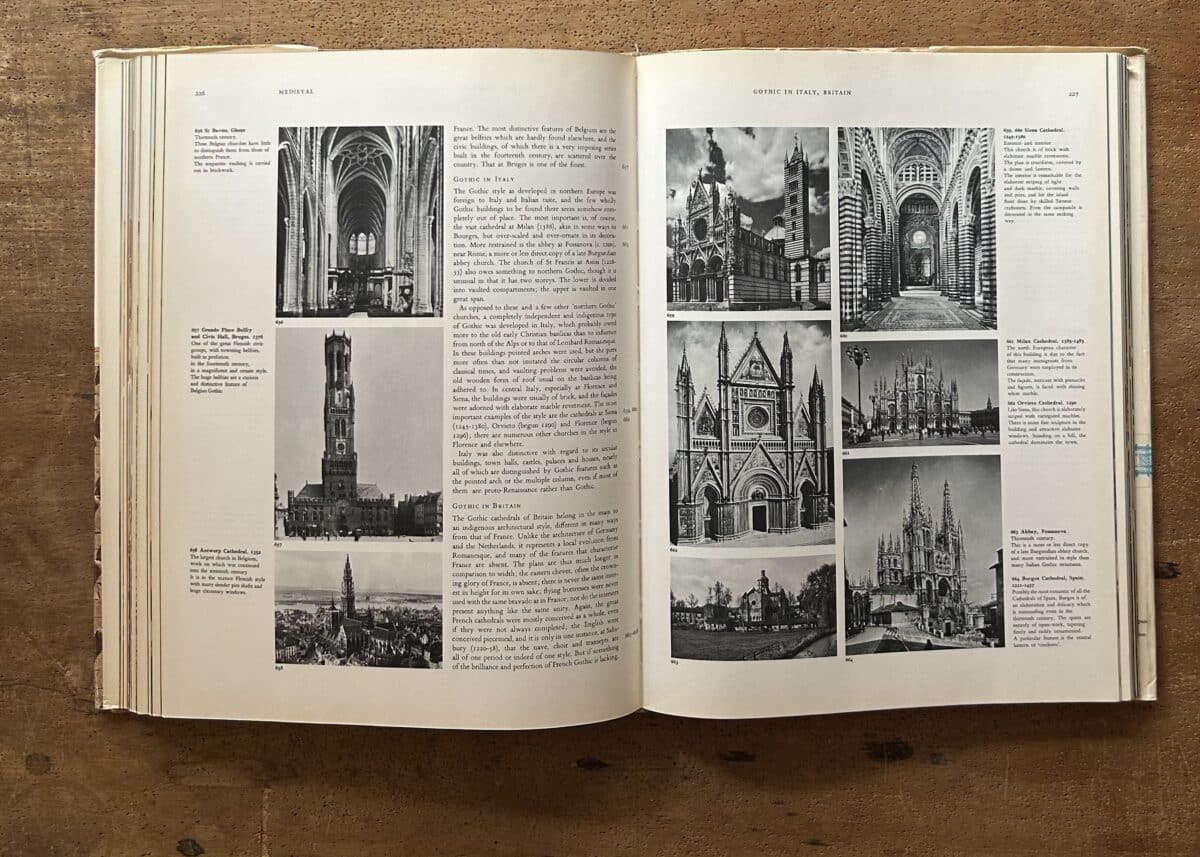

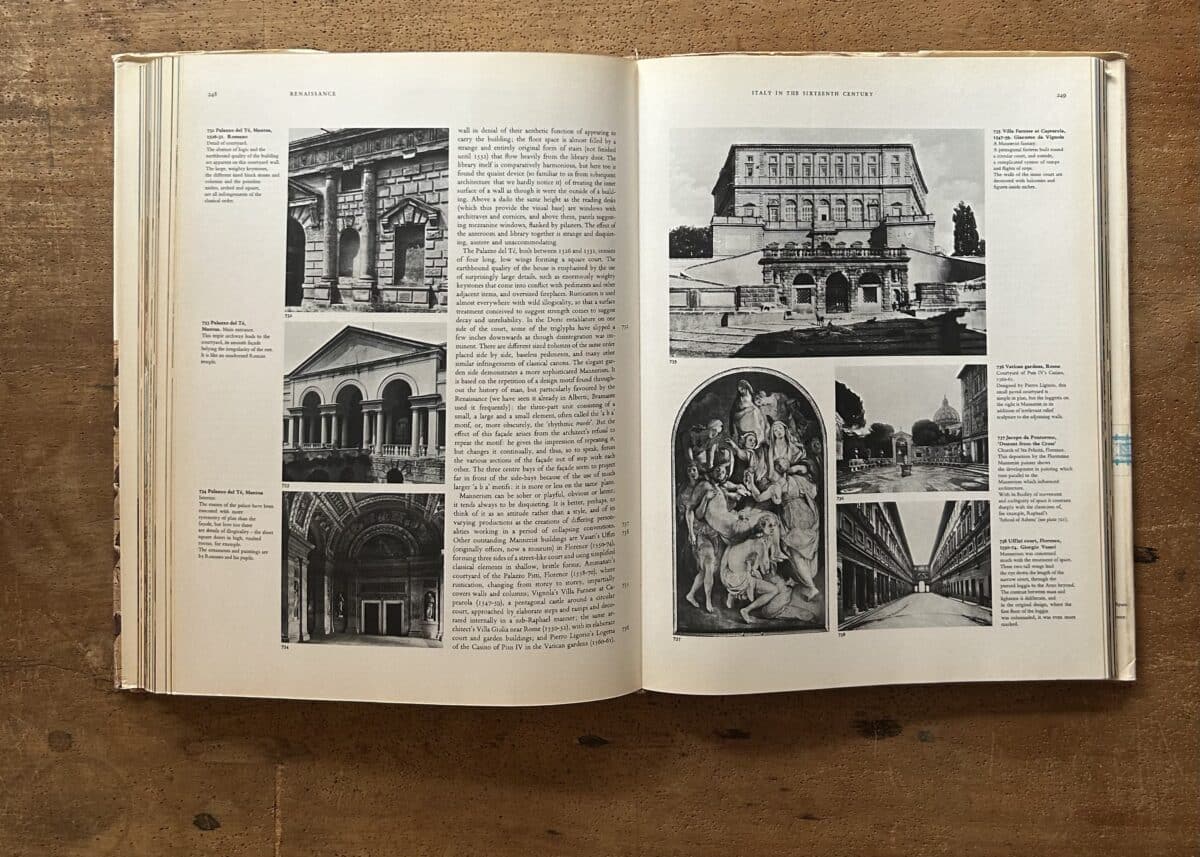

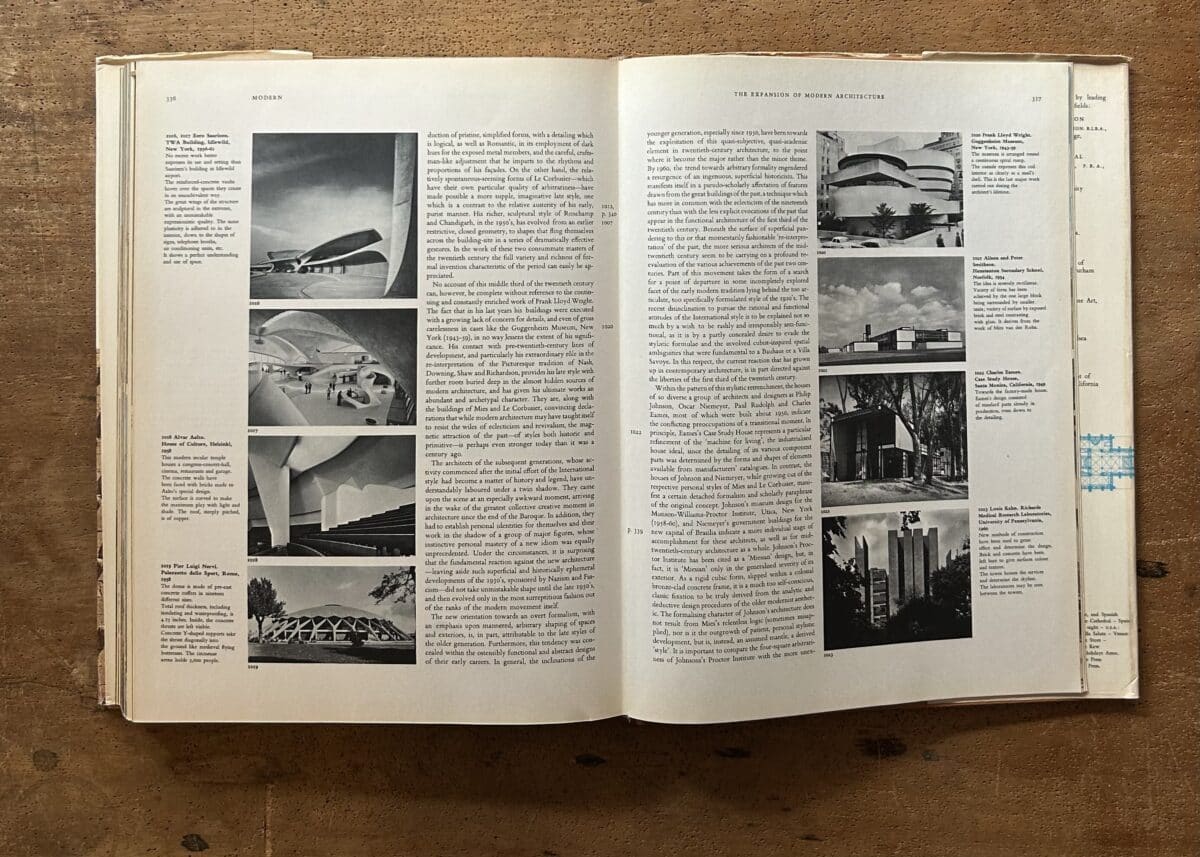

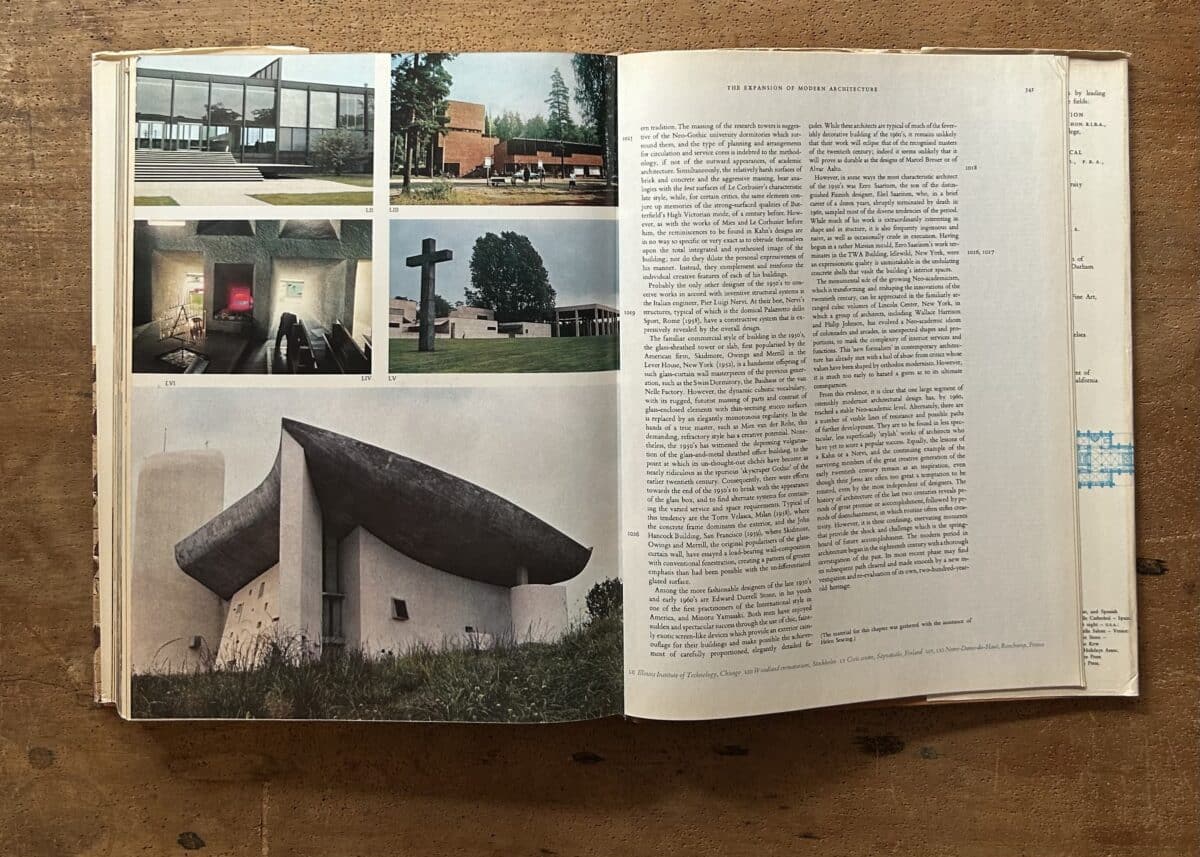

We found a plausible candidate: World Architecture: An Illustrated History, published by Paul Hamlyn in 1963. There was a PDF online. World Architecture matched Natalini’s list. It featured the Taj-Mahal on page 166, and the Eiffel Tower on page 307. We ordered a copy.

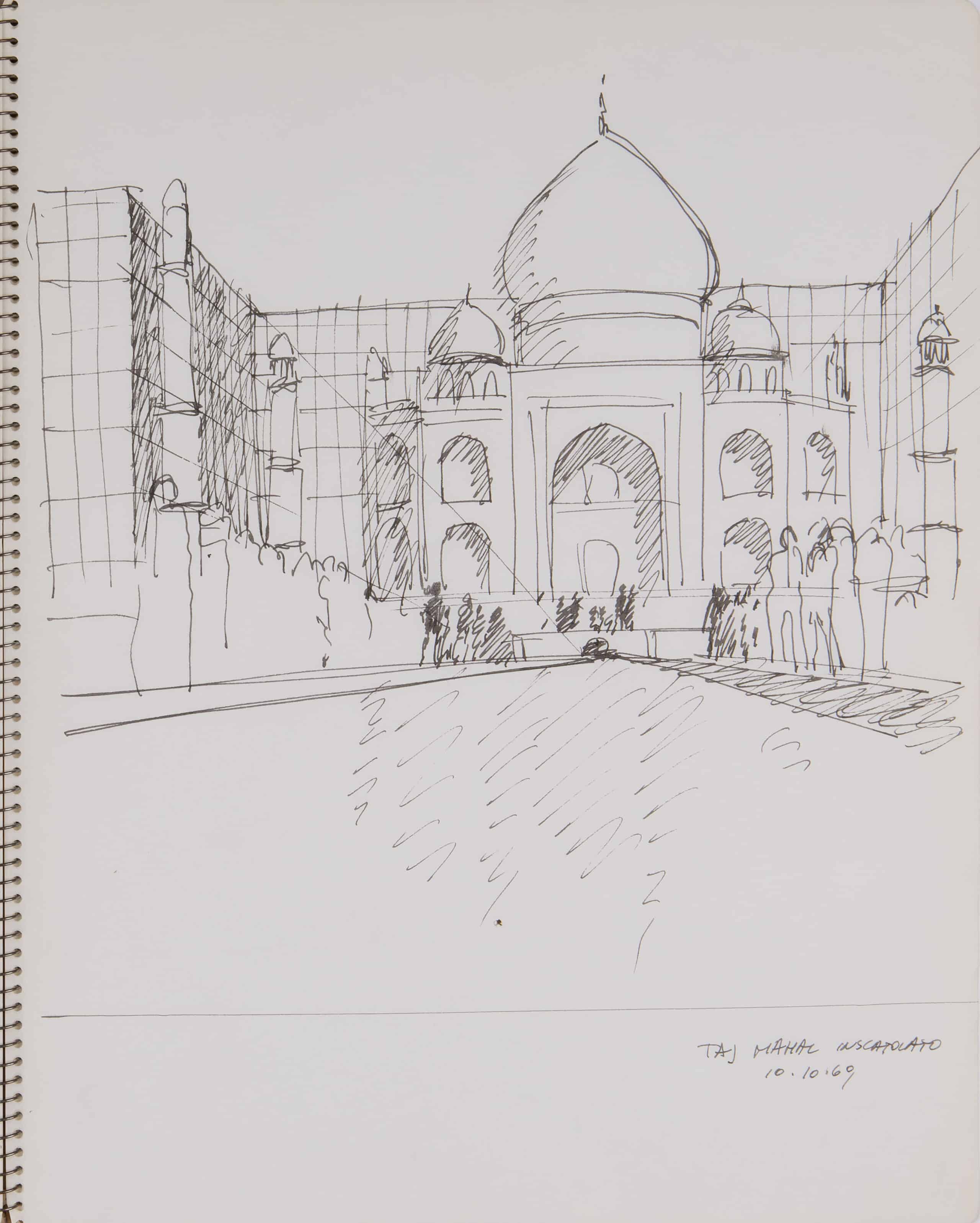

As the Continuous Monument moved through time and space, Natalini, seeking references, turned the pages of World Architecture. It’s quite a nice image: Natalini sitting in an office, or a studio, and flicking through a hardback, noting down page numbers when he found something he liked. You wonder if he made his decisions based on the notoriety of the buildings, or if it was more to do with the angle of the photograph, or whether the images presented enough sky. When the monument engages with existing architectures, the buildings feel safe, cradled by the grid.

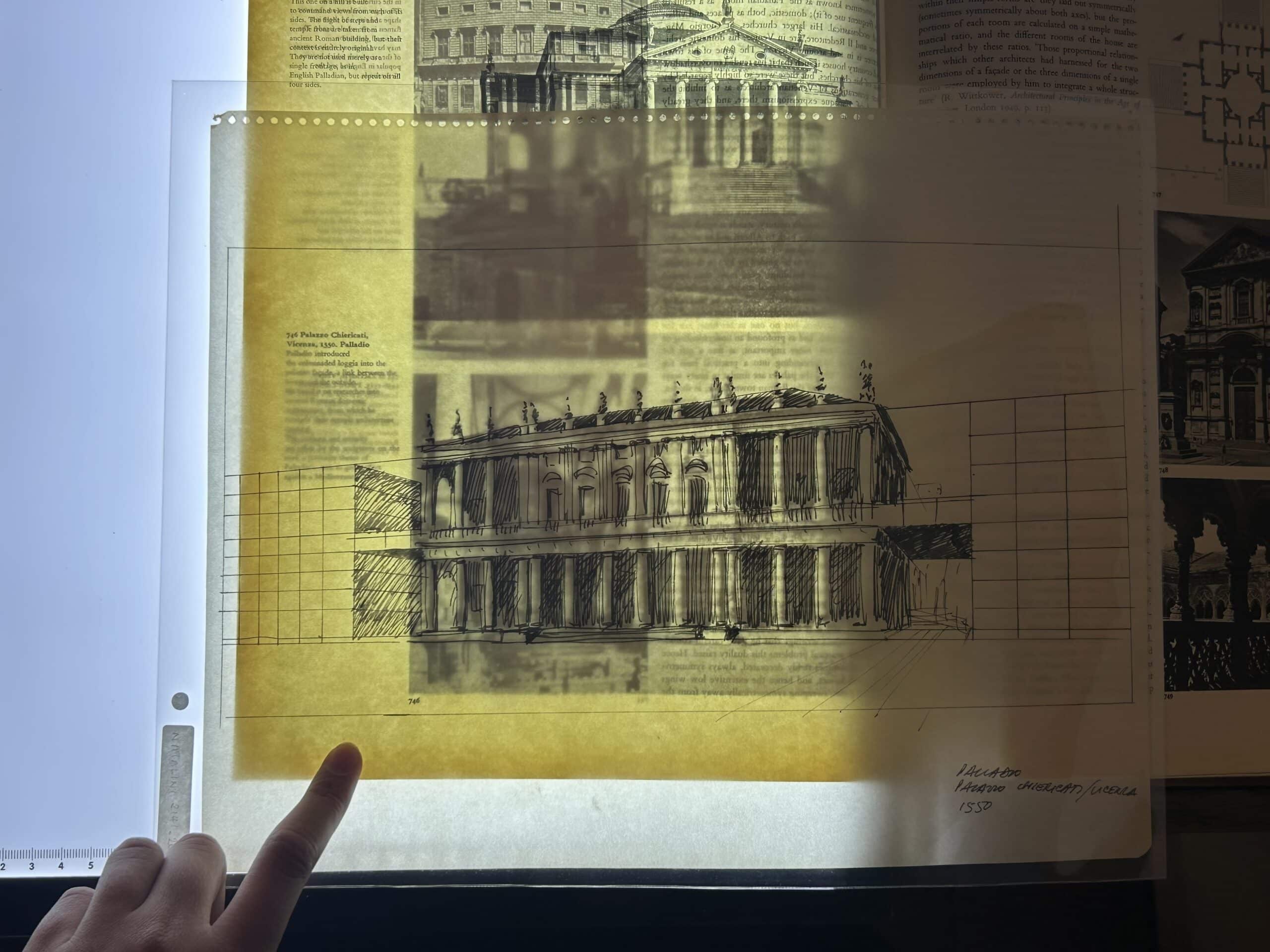

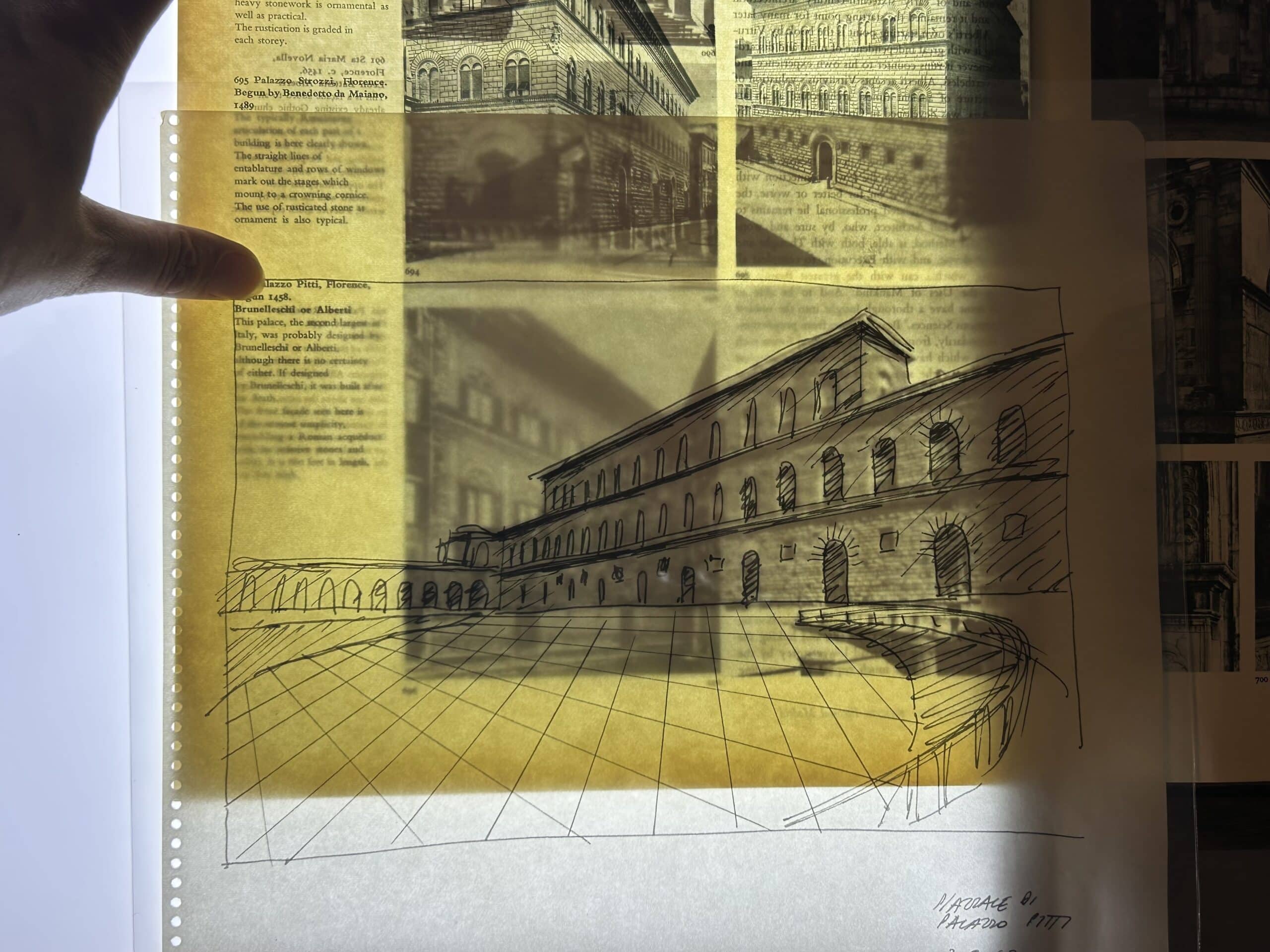

The photographs in the book became reference material.

And in some instances, if the scale and perspective of the building were just right, he could trace the pages directly.

– Sophia Banou