Trevor Dannatt’s Riyadh Mosque: A Study in Sacred Space and Cultural Juxtaposition

Saudi Arabia’s Quest for Modern Identity and the Urban Transformation of Riyadh

Beginning in the 1960s, Saudi Arabia embarked on an ambitious building programme, resulting in numerous architectural projects recognised internationally for their remarkable scale as well as their innovative architectural and engineering solutions.[1] This extensive initiative gained substantial momentum from the significant increase in government revenues following the 1973 price-setting agreement by the Organisation of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC).[2] Under King Faisal bin Abdulaziz Al Saud (r. 1964–1975), Saudi Arabia pursued modernisation by thoughtfully blending contemporary design principles with traditional cultural values.[3] This balanced approach was particularly evident in key projects such as the College of Petroleum and Minerals in Dhahran (1963–1978), designed by the American firm Caudill, Rowlett, Scott (CRS); the Intercontinental Hotel and Conference Centre in Makkah (1963–1974), designed collaboratively by Rolf Gutbrod and Frei Otto; and and an unbuilt proposal for a major sports facility by Kenzo Tange in Riyadh (1968).

The expansion of Riyadh from relatively small regional towns into an urban centre was guided by the planning framework devised by Greek architect Constantinos Doxiadis.[4] Implemented from the late 1960s through the 1970s, this framework relied on the superblock—a 2 × 2 kilometre, self-contained unit—as its primary organising element, enabling the city to absorb population growth, meet infrastructure demands and support systematic outward growth. Doxiadis’s master plan introduced a rectilinear grid that allocated separate residential, commercial, governmental and recreational zones, establishing a clear urban hierarchy for efficient service distribution. Each superblock was specified to contain its mosque, shops, schools and healthcare facilities, linking metropolitan-scale planning with neighbourhood-level needs.[5] This structure improved functional efficiency and provided a foundation for significant institutional buildings, shaping Riyadh’s evolving urban identity.

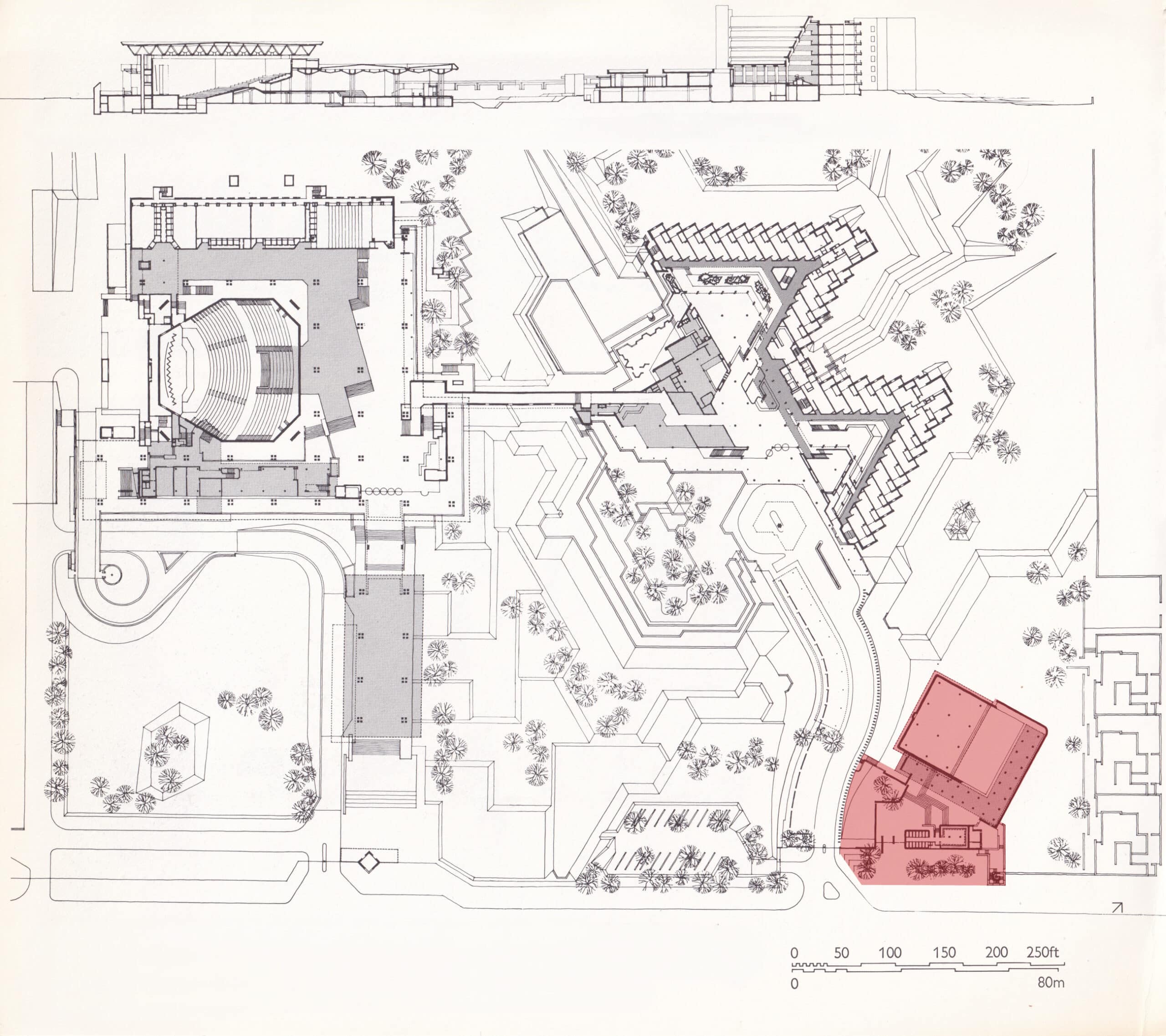

Within Saudi Arabia’s modernisation programme, the Riyadh Conference Centre, Hotel and Mosque, designed by Trevor Dannatt, occupies a pivotal position. The complex originated from an international competition held in 1966, the brief of which, issued on King Faisal’s instructions, required that a mosque accompany the conference and hotel functions; Dannatt’s winning scheme was subsequently reviewed and endorsed by the King during a visit to London in 1967.[6] The complex was conceived to accommodate high-level national and international conferences and seminars, positioning it as a future cultural hub for Riyadh, while the addition of the mosque supplied a civic-religious centre that framed the ensemble’s diplomatic and commercial functions within an explicitly Islamic identity.

The Architecture of Dannatt’s Riyadh Mosque: Architectural Juxtaposition as Creative Conservation

The architectural character of the mosque is defined by formal restraint, precise spatial clarity, and a profound sensitivity to cultural and environmental context [7]. Situated at the southern edge of the conference complex, the mosque occupies a key location at the transitional boundary between the formal institutional fabric and the adjacent residential districts. This sitting establishes a mediating zone between public and private realms, allowing the building to operate as both a visual terminus and a civic threshold. Its orientation and approach sequence calibrate urban scale with human intimacy, ensuring that the mosque does not merely serve functional requirements but also enacts a spatial dialogue between monumental order and domestic quietude.

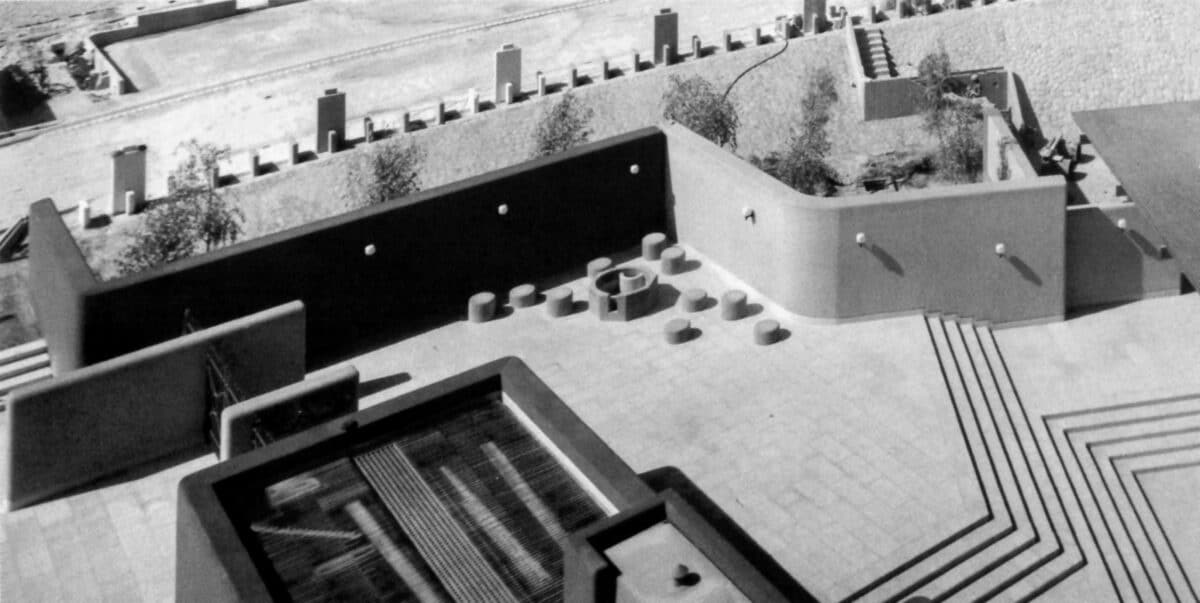

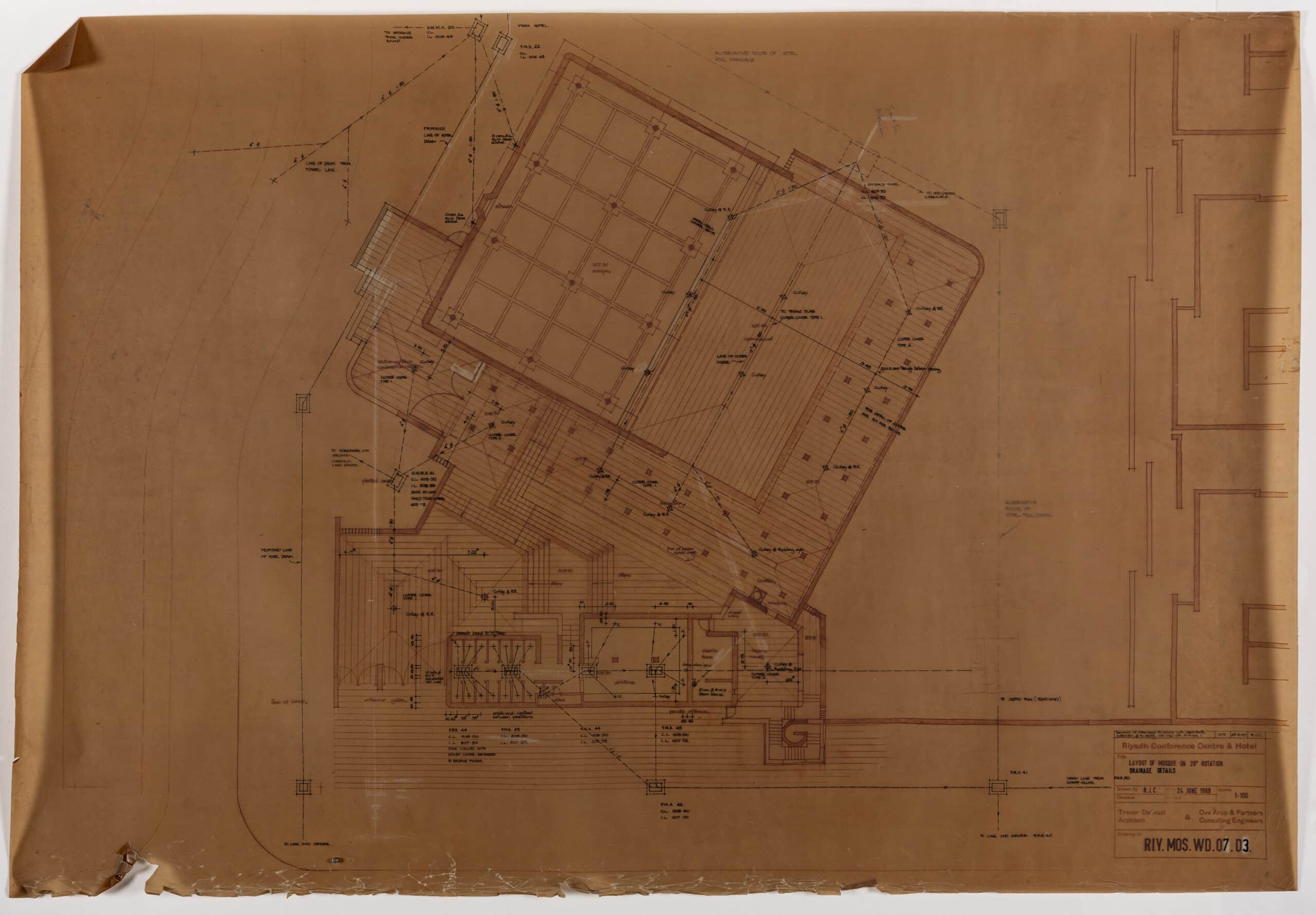

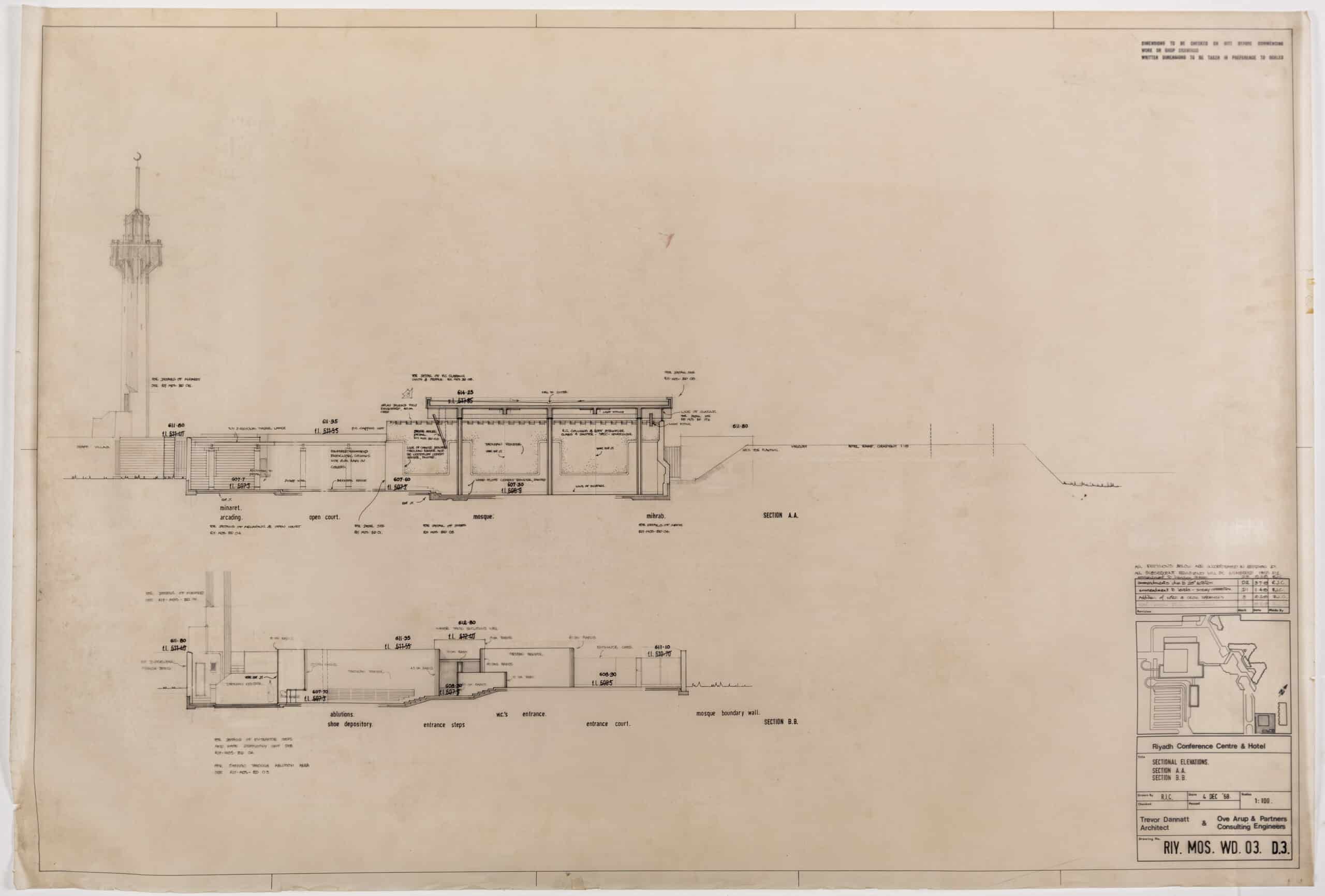

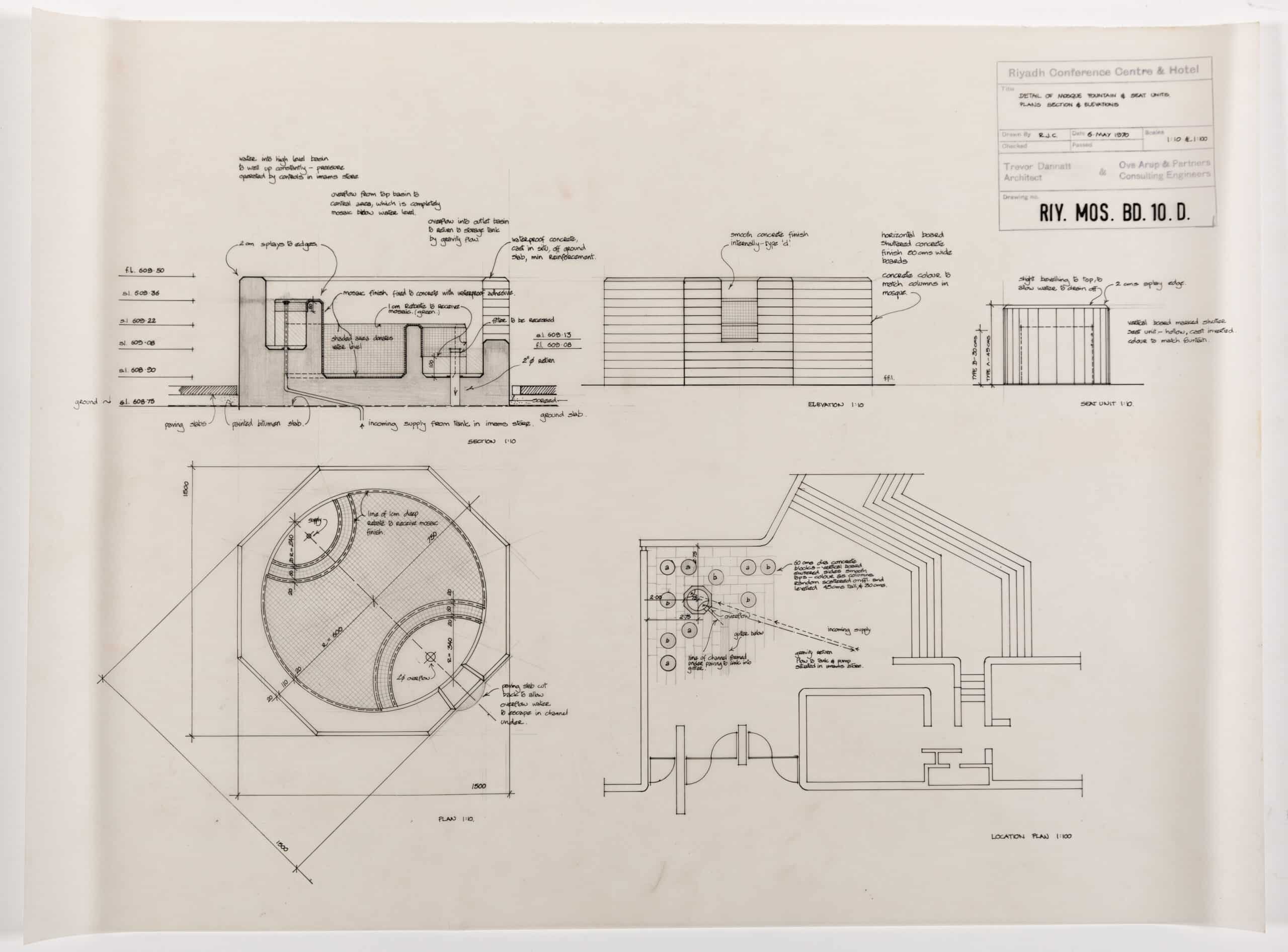

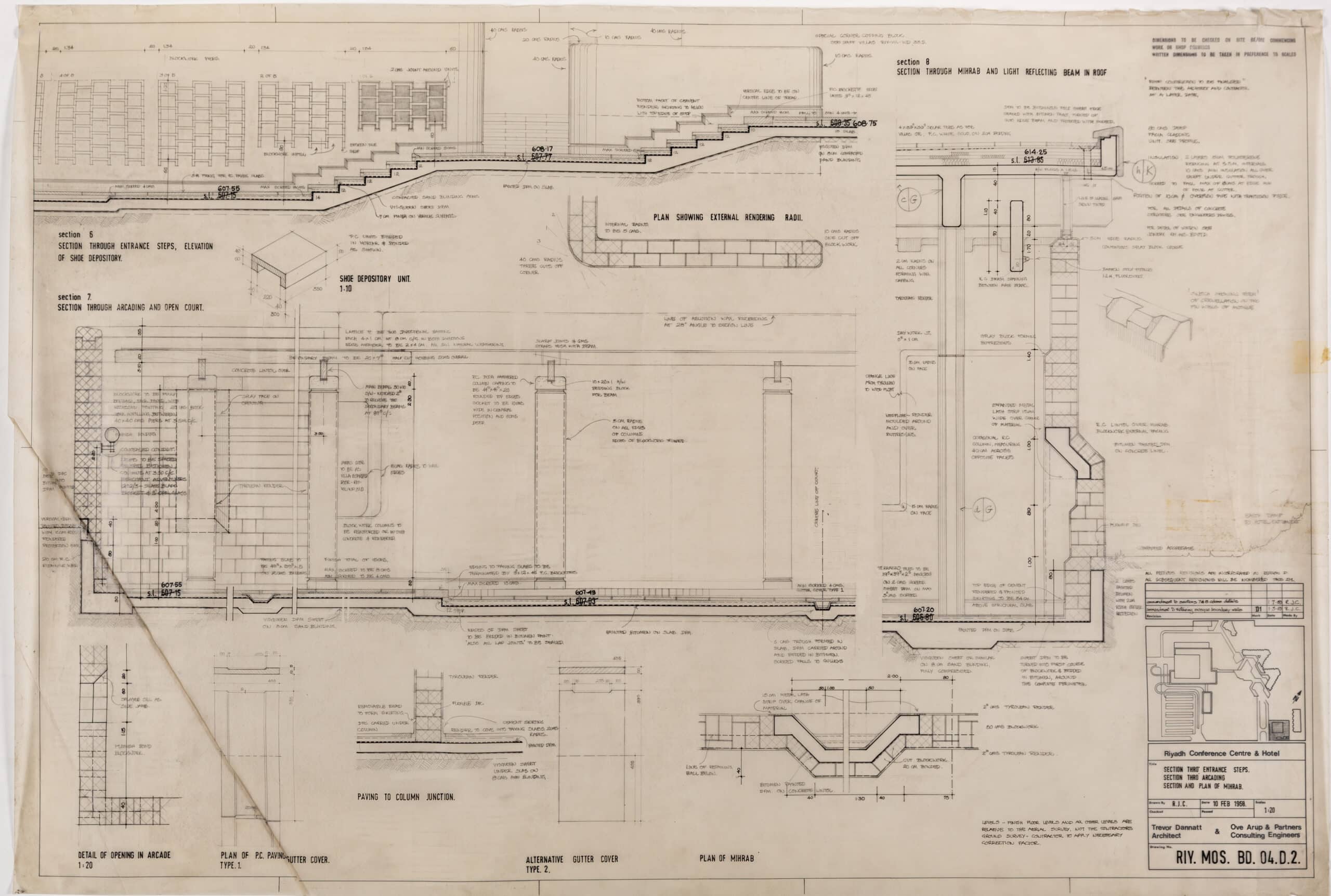

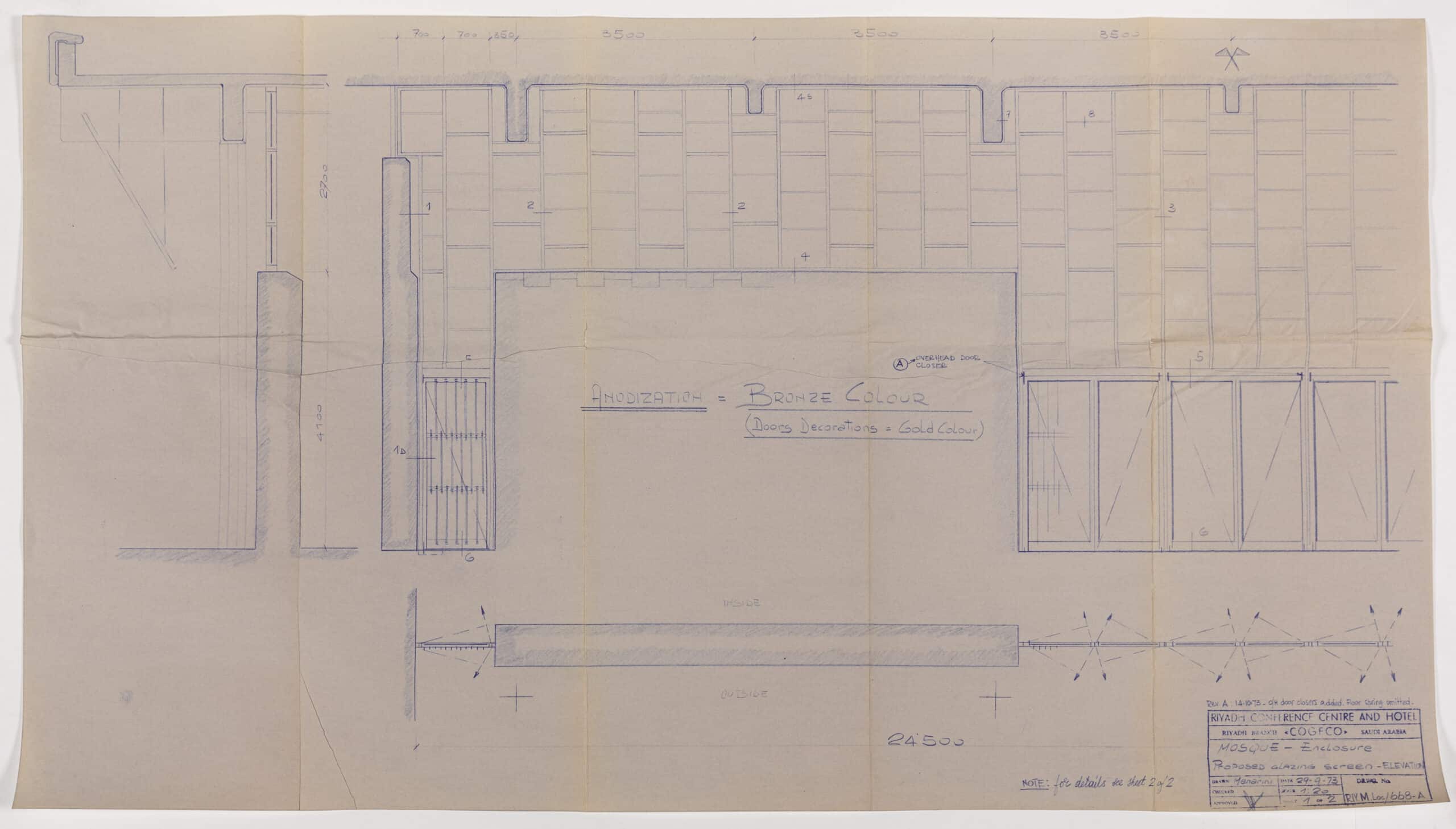

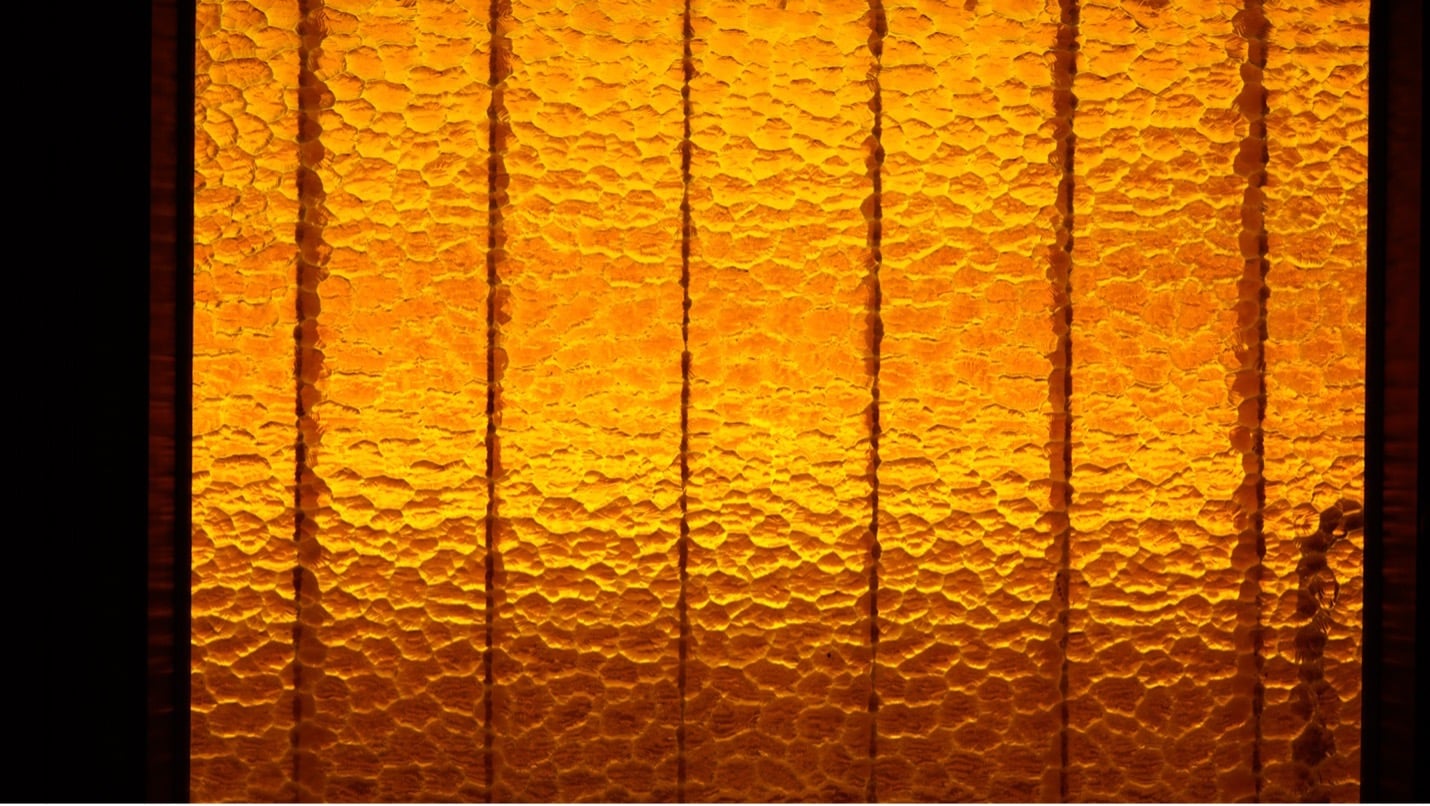

The spatial organisation of the mosque reflects the careful choreography of devotional movement and bodily preparation. The visitor’s journey unfolds sequentially, beginning at an elevated entrance courtyard featuring fixed seating and a central fountain. From this ceremonial entry point, the path descends gently via steps to a lower transitional ablution terrace, clearly defined and functionally specific, before entering the prayer courtyard and finally arriving at the enclosed prayer hall. This sequence of spaces is articulated by shaded colonnades, bronze-anodised aluminium screens, and finely crafted timber grilles (kafess), carefully controlling the entry of natural light and sensory stimulation to foster introspection and a heightened sense of spiritual preparation.

This spatial logic draws explicitly upon regional precedents of traditional Saudi mosque configurations, particularly enclosed courtyard-and-hall typologies common in Najdi architectural heritage. The supervisory committee set the brief with simple and minimally prescriptive liturgical terms, calling for a mosque reflecting regional norms, particularly those rooted in Najdi and regional architecture. These, along with spatial elements such as pillared halls glimpsed in Riyadh’s older mosques, became the basis for a spatial arrangement that invites an open-ended interpretation of their experiential and civic potential. Rather than a literal reproduction, the result is an austere yet eloquent architectural response grounded in cultural memory and expressive restraint. However, here, tradition is reconsidered through modernist rigour. The mosque’s plan consists of two interlocking U-forms: an inner U-shaped roofed prayer hall and an outer open U-shaped courtyard. A perimeter colonnade bordered by timber grilles envelops the prayer courtyard, turning orthogonally to connect seamlessly back to the entrance courtyard. Decorative tiled screening within glazed apertures further accentuates the ceremonial transition between public arrival and private devotion, offering visual permeability and symbolic thresholds.

While geometrically controlled, the prayer hall acquires visual depth through fine‑grained textures, layered shadow patterns, and the interlocking volumes of hall and courtyard. The hall is organised on a five‑by‑five grid of octagonal reinforced‑concrete columns that support an exposed coffered roof slab, recalling hypostyle precedents while asserting a contemporary structural language. The material palette is calibrated to Riyadh’s climate: brown acid‑etched concrete for the frame, precision‑shuttered concrete fascias to the beams, and light Tyrolean render on interior blockwork. Externally, rounded projections and darker tones moderate glare and reduce apparent mass. The disciplined grid, carefully modulated lighting, and climate‑responsive finishes create layered shadows and subtle textures, giving the hall visual depth while integrating modern construction with longstanding liturgical and environmental requirements.

The mihrab exemplifies architectural restraint: a shallow, unadorned recess whose spiritual presence is achieved through spatial articulation rather than ornamental display, echoing the plain, earthen character of traditional Najdi mosques in central Arabia and the broader Islamic principle that prayer spaces should minimise visual distraction. Clerestory glazing brings daylight into the prayer hall on three sides; at the qibla wall, that light is moderated by a suspended timber screen, producing a soft, indirect wash that focuses attention on the mihrab without glare. This careful modulation of natural illumination, integrated with the structural rhythm of octagonal concrete columns and roof beams, provides a subdued focal point that enhances worshippers’ concentration while maintaining the overall compositional balance of the space.

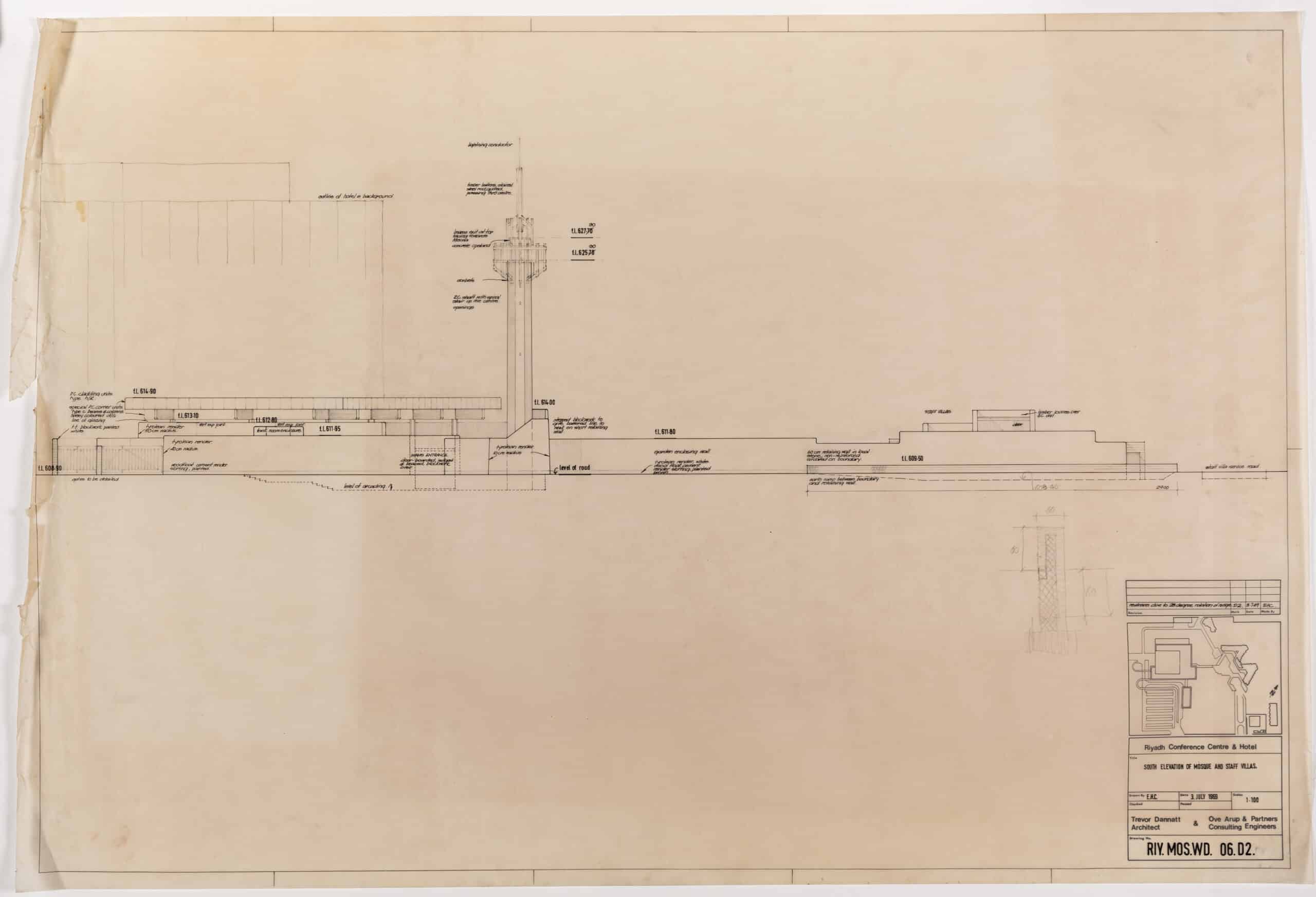

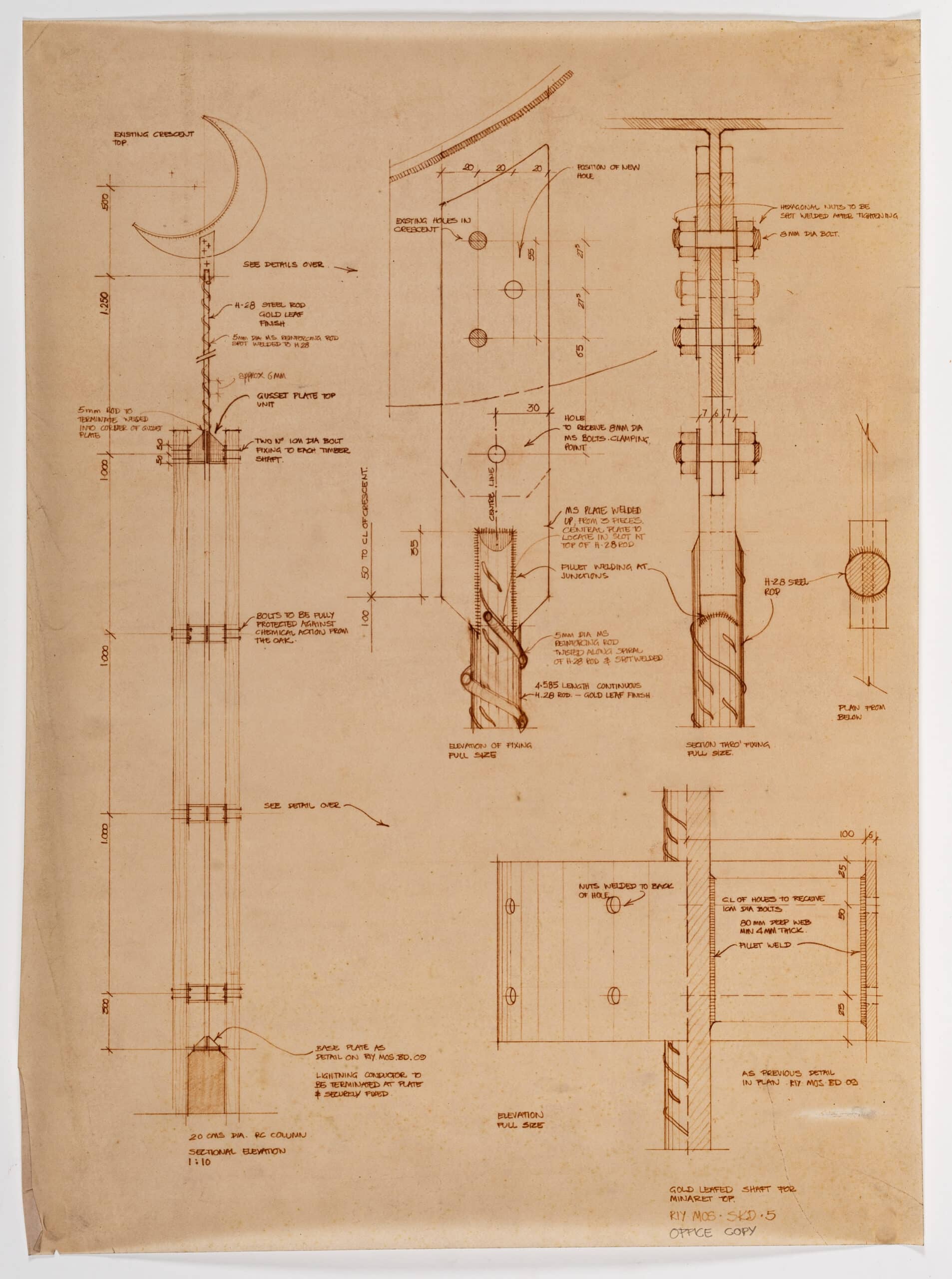

Dannatt’s minaret emerges as a critical threshold within the mosque complex, operating simultaneously as a vertical counterpoint and urban signifier. The structure’s tripartite composition—comprising a slender concrete shaft, precisely detailed oak superstructure, and gold-leaf crescent finial—articulates a material progression from terrestrial to celestial domains. As evidenced in the architect’s technical drawings, the minaret’s constructional logic reveals Dannatt’s modernist sensibility through its tectonic expression: structural connections are neither concealed nor celebrated but resolved with quiet precision. The concrete column, measuring 20 centimetres in diameter, establishes a vertical datum that mediates between human and cosmic scales, while the timber elements introduce a haptic dimension through material contrast. Unlike traditional minarets that rely on ornamental excess or historical quotation, Dannatt’s interpretation achieves its symbolic resonance through proportional relationships and material juxtaposition. This approach exemplifies what might be termed a ‘reticent monumentality’—a condition where symbolic presence is achieved not through dominating scale or decorative elaboration but through carefully calibrating form, material, and light. The gold-leaf crescent, catching and reflecting sunlight at different times of day, transforms the otherwise static element into a temporal register, marking the minaret as both the physical structure and an instrument of celestial observation.

These design choices reflect Dannatt’s commitment to an ‘architecture of background’: a built environment that supports experience without dominating it. In this approach, spirituality is expressed not through decorative excess or historical pastiche but through calibrated proportions, modulated light, and spatial thresholds that guide the body and the senses. Thus, the mosque embodies a quiet architecture of reciprocity—negotiating between sacred function and climatic response, cultural continuity and modern reinterpretation—offering a compelling model for contemporary Islamic architecture that is contextual, thoughtful, and enduring.

The mosque is an integral part of the architectural ensemble it occupies, situated between the monumental formality of the conference centre and the flowing, organic shapes of the hotel. Together, these structures create a poetic figure-ground relationship, where the mosque serves as a mediating presence, modest in scale yet rich in spatial rhythm and ritualised sequencing. While the conference centre asserts geometric clarity and civic monumentality, and the hotel emerges from the landscape with terraced informality, the mosque anchors the composition through a procession of spatial thresholds: pergola, courtyard, ablution area, and prayer hall. This contrast is not merely visual but also symbolic, reflecting Dannatt’s belief in ‘creative conservation’ through meaningful juxtaposition—an architecture that mediates difference rather than imposes uniformity.

This layered architectural logic supports experiential clarity and resonates with broader theories of Islamic urbanism, as articulated in Saleh Al-Hathloul’s The Arab-Muslim City: Tradition, Continuity and Change in the Physical Environment. Al-Hathloul critiques conventional Western planning paradigms—particularly zoning models that rigidly separate functions—advocating instead for traditional Arab-Muslim spatial practices that prioritise ritual, social interaction, and community cohesion over abstract functionalism. Central to his argument is a ‘code of conduct’ embedded within Islamic urban environments, where spatial decisions about access, visibility, and orientation are guided by social norms and religious values rather than typology or infrastructure alone.[8] Dannatt’s mosque directly embodies these principles, positioning itself not as a detached icon but as a relational and civic anchor within its context. Its spatial choreography reflects the logic of Islamic ritual—moving through calibrated thresholds that guide the visitor from the public realm into sacred space, echoing the process of spiritual preparation. Moreover, Dannatt’s responsiveness to intuitive alignment and relational proximity—particularly in adjusting the qibla direction after consultation with local religious authorities—demonstrates a sensitivity to lived practice over formal abstraction. In this way, the mosque becomes not merely a building but a vessel of cultural continuity, integrating architectural form, spiritual function, and ethical rootedness into a unified spatial experience.

Sherban Cantacuzino in his 1975 review of Trevor Dannatt’s Riyadh conference centre complex, singles out the mosque as ‘the most eloquent building on the site,’ arguing that its spare forms reveal both the architect’s non-conformist pedigree and a perceptive grasp of ‘desert puritanism’—clean lines, plain surfaces, and harmonious geometric shapes. In addition, Cantacuzino praises the court’s play of light and shadow, the unornamented walls whose occasional thickening merely ‘models’ the surface, and the structurally independent roof of octagonal columns and beams. Nevertheless, he laments later concessions to comfort—tinted clerestory glazing and a partition that severs the court from the covered prayer space, as dilutions of the mosque’s principled austerity.[8] Furthermore, drawing on the ideas of Christian Norberg-Schulz, who argued that architecture becomes symbolic by embodying a community’s core values, Cantacuzino suggests that Dannatt succeeded in expressing national identity through form.

In ‘Towards a Critical Regionalism: Six Points for an Architecture of Resistance’, Kenneth Frampton calls for an architecture that reinterprets tradition rather than imitates it, mobilising cultural memory as a medium of resistance. [10] Rather than resorting to nostalgic pastiche or simulating vernacular forms, Trevor Dannatt’s mosque rearticulates regional identity through tectonic clarity, site sensitivity, and material expressiveness. The interplay of filtered natural light and carefully proportioned spatial volumes reflects what Frampton describes as an architecture grounded in the poetics of construction and attuned to the tactile dimension of experience. Situated within Riyadh’s rapidly transforming urban fabric, the mosque asserts itself as a bounded and deliberate domain, a space of spiritual anchoring that counters the amorphous sprawl of surrounding development. Through this critical reworking of tradition, Dannatt’s design resists the spectacle of scenographic representation and instead operates as a tectonic fact, quietly asserting a culturally situated modernity that unfolds in the interstices between globalisation and locality.

Juhani Pallasmaa’s conceptualisation of existential continuity, articulated in Newness, Tradition and Identity, provides another compelling interpretative lens for understanding Dannatt’s Riyadh Mosque.[11] Pallasmaa critiques contemporary architecture’s fixation on visual novelty, advocating designs rooted in shared cultural memory, atmospheric nuance, and sensory richness. Dannatt’s restrained aesthetic—textured concrete surfaces evocative of traditional adobe, careful modulation of light and shadow, and subtle spatial transitions—exemplifies this continuity. Rather than quoting history literally, Dannatt evokes historical resonance through the thoughtful organisation of space, locally resonant materials, and curated sensory experiences, situating visitors within a meaningful cultural continuum.

Dannatt’s commitment to architectural juxtaposition—the purposeful dialogue between new interventions and existing contexts—is evident throughout the Riyadh complex. As articulated in his Creative Conservation lecture, Dannatt argued that ‘new buildings should assert their contemporary identity while remaining deeply engaged with historical and cultural contexts… not through mimicry but through meaningful contrast.’[12] This position distances his work from the tabula rasa modernism dominant in much of the international architecture of the period, as well as from the historicist pastiche often employed in culturally sensitive contexts. In Riyadh, juxtaposition operates not only as a visual contrast but as a sustained architectural dialogue. The formal austerity of the conference centre and mosque stands in deliberate counterpoint to the informal, domestic intimacy of the hotel. Each element sharpens the spatial and symbolic presence of the other, generating a dynamic narrative within the broader urban framework—one that unfolds through movement and inhabitation rather than as a fixed compositional tableau. This strategy aligns with Dannatt’s broader conviction that architecture should ‘create ambience beyond the lab concept of environment… a milieu which connects us to the poetry of living, heightening our awareness of today as part of yesterday and the day before yesterday.’ [13]

Notes

- Faisal A. Al-Mubarak, ‘Oil, urban development and planning in the Eastern Province of Saudi Arabia: The case of the Arab American Oil Company in the 1930’s–1970’s’, Journal of King Saud University – Architecture & Planning, 11 (1999), 31–51.

- David M. Wight, The petrodollar era and relations between the United States and the Middle East and North Africa, 1969–1980 (Doctoral dissertation, University of California, 2014).

- Walter McQuade, ‘The Arabian building boom is making construction history’, Fortune, 94(3) (1976, September), 112.

- Saleh Al-Hathloul, ‘Riyadh development plans in the past fifty years (1967–2016)’, Current Urban Studies, vol. 5, no. 1 (2017), 97–120.

- Mohammed A. Eben Saleh, ‘The evolution of planning & urban theory from the perspective of vernacular design: MOMRA initiatives in improving Saudi Arabian neighbourhoods’, Land Use Policy, vol. 18, no. 3 (2001), 179–190.

- Trevor Dannatt, ‘Conference centre, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia,’ Architectural Design, vol. XXXVII (Mar. 1967), 135.

- Trevor Dannatt & Partners, ‘Mosque in Riyadh’, RIBA Journal, vol. 83, no. 6 (Jun. 1976).

- Saleh Al-Hathloul, The Arab-Muslim City: Tradition, Continuity and Change in the Physical Environment(Riyadh: Ministry of Municipal and Rural Affairs, 2008).

- Sherban Cantacuzino, ‘Conference centre and hotel, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia’, The Architectural Review, vol. CLVII, no. 938 (Apr. 1975), 215–219.

- Kenneth Frampton, ‘Towards a critical regionalism: Six points for an architecture of resistance’, in The Anti-Aesthetic: Essays on Postmodern Culture, H. Foster, Ed., Bay Press, 1983.

- Juhanni Pallasmaa, ‘Toward an architecture of humility’, Docomomo Journal, no. 49 (2013), 28–33.

- Trevor Dannatt, Creative conservation, audio-visual lecture, Pidgeon Digital, 1992, <https://www.pidgeondigital.com/talks/creative-conservation/> [accessed 27 May 2025]

- Trevor Dannatt, Works and Words (London: Black Dog Publishing, 2008), 8.

Majed Alghaemdi is a faculty member at King Saud University and a PhD candidate in the Department of Architecture and Built Environment at the University of Nottingham. He holds a master’s degree from the Southern California Institute of Architecture (SCI-Arc). His research focuses on spatial experience, museum design, and embodied perception, with particular attention to the intersections of phenomenology, space syntax, and architectural theory.

– Adrian Dannatt