Emilio Ambasz’s ‘Italy, The New Domestic Landscape’ (1972)

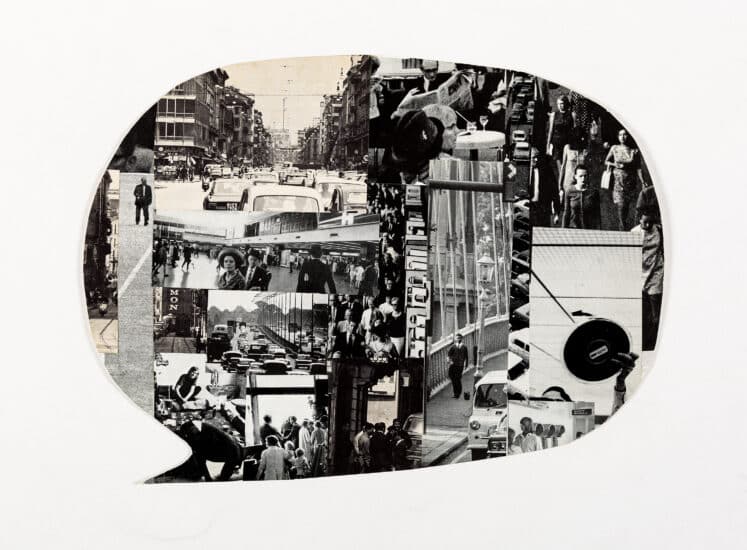

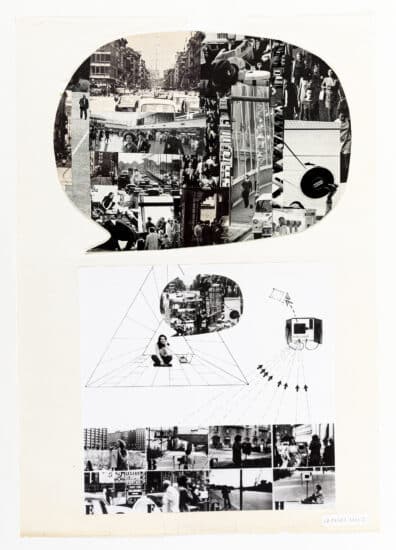

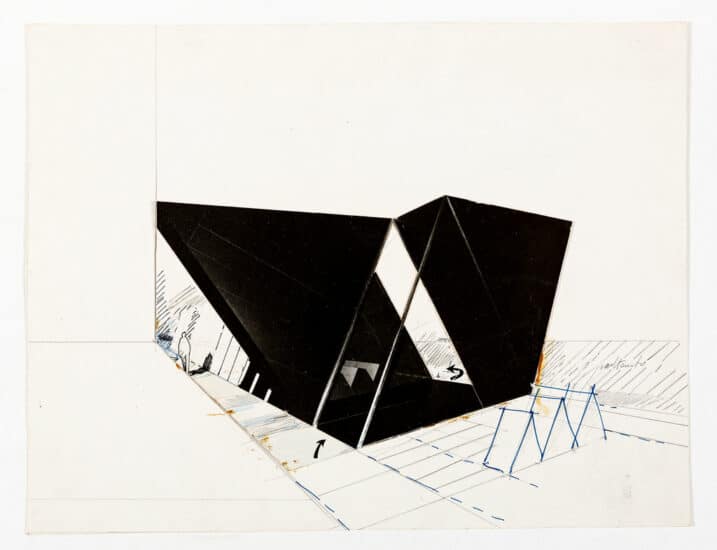

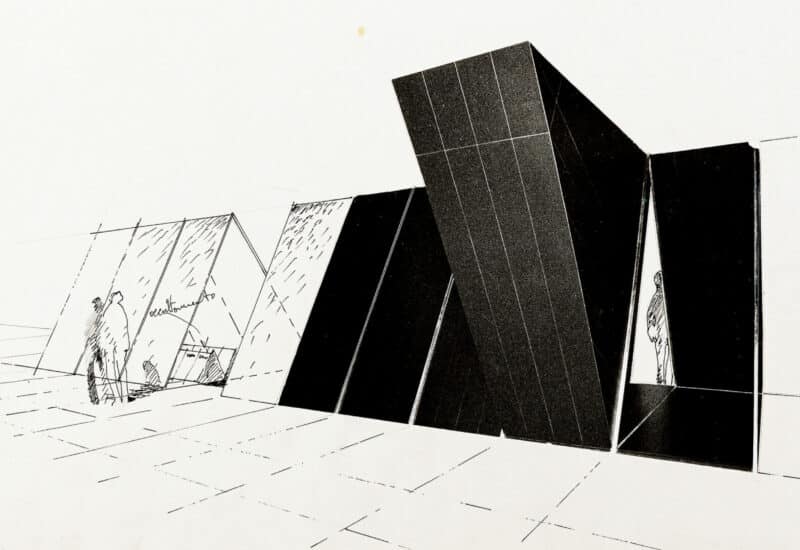

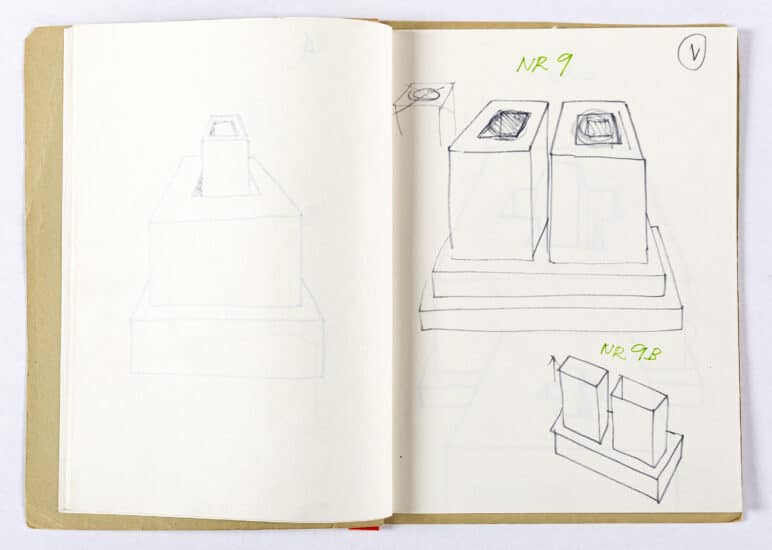

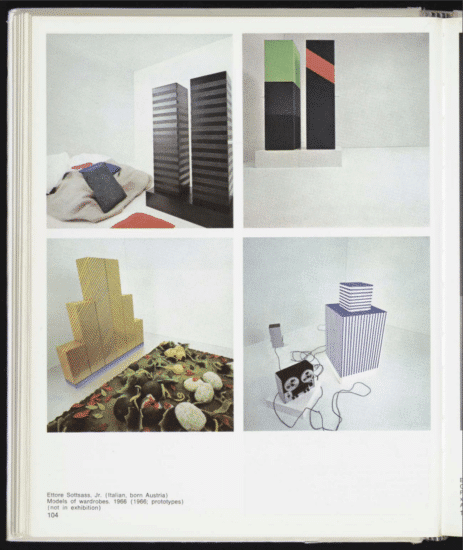

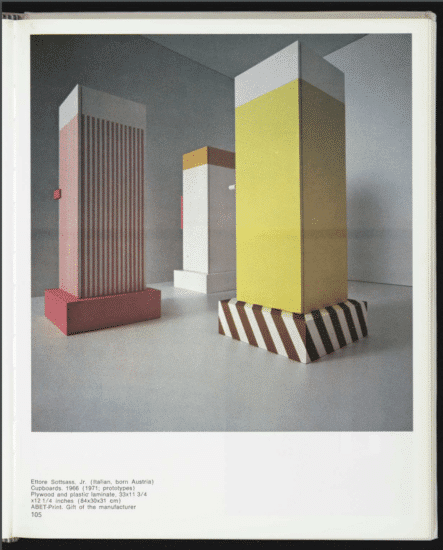

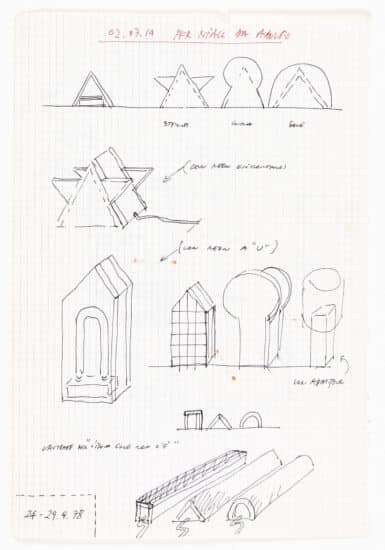

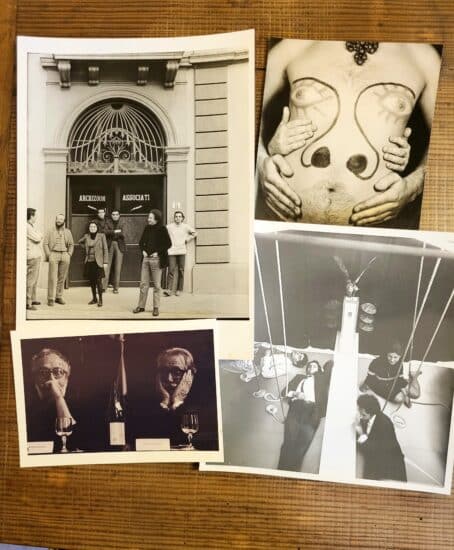

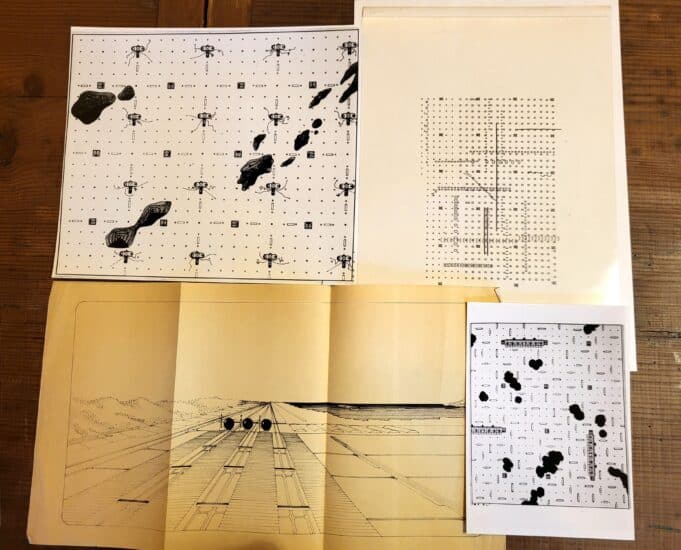

A PROJECT SCRAPBOOK

– Editors

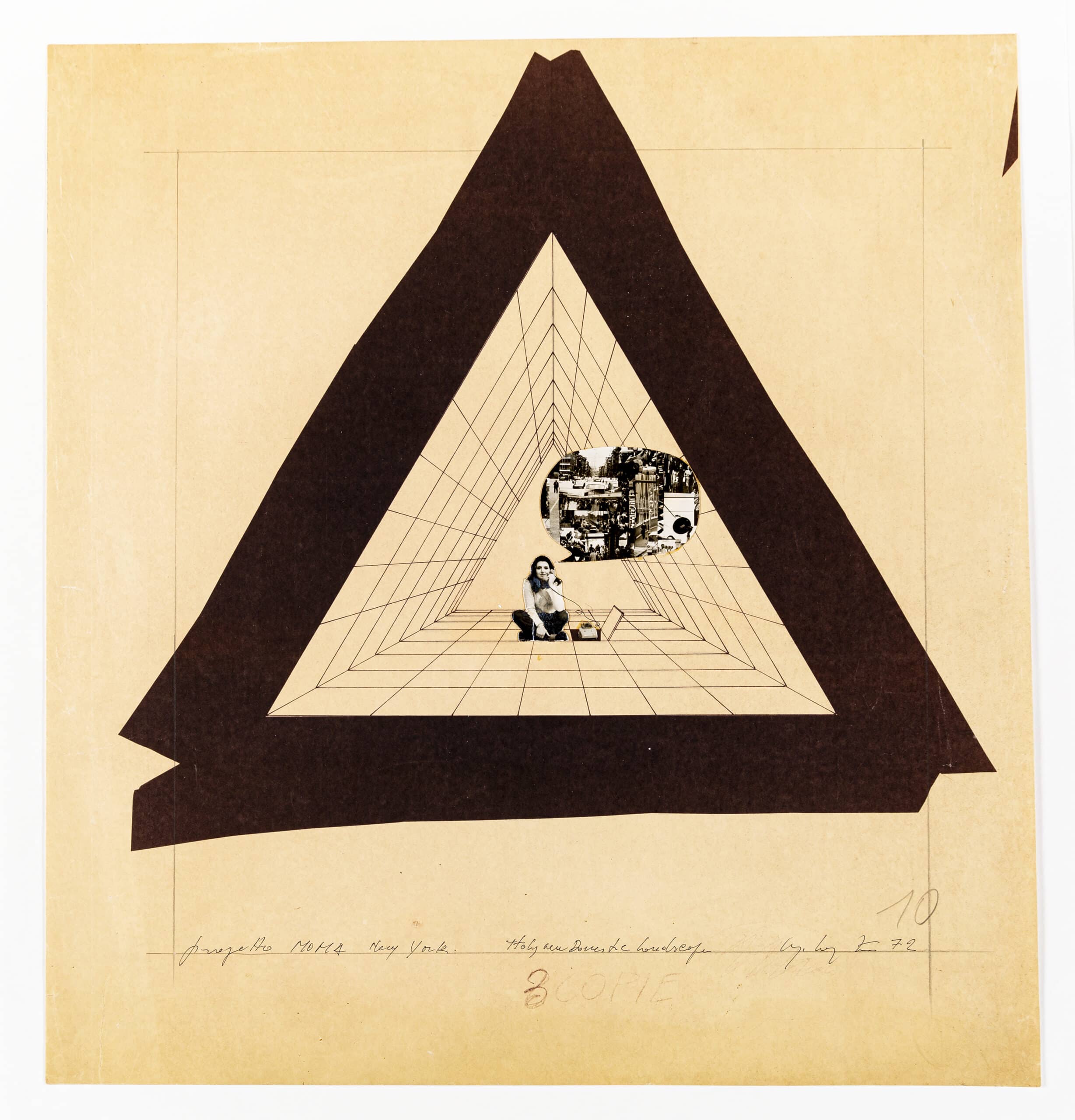

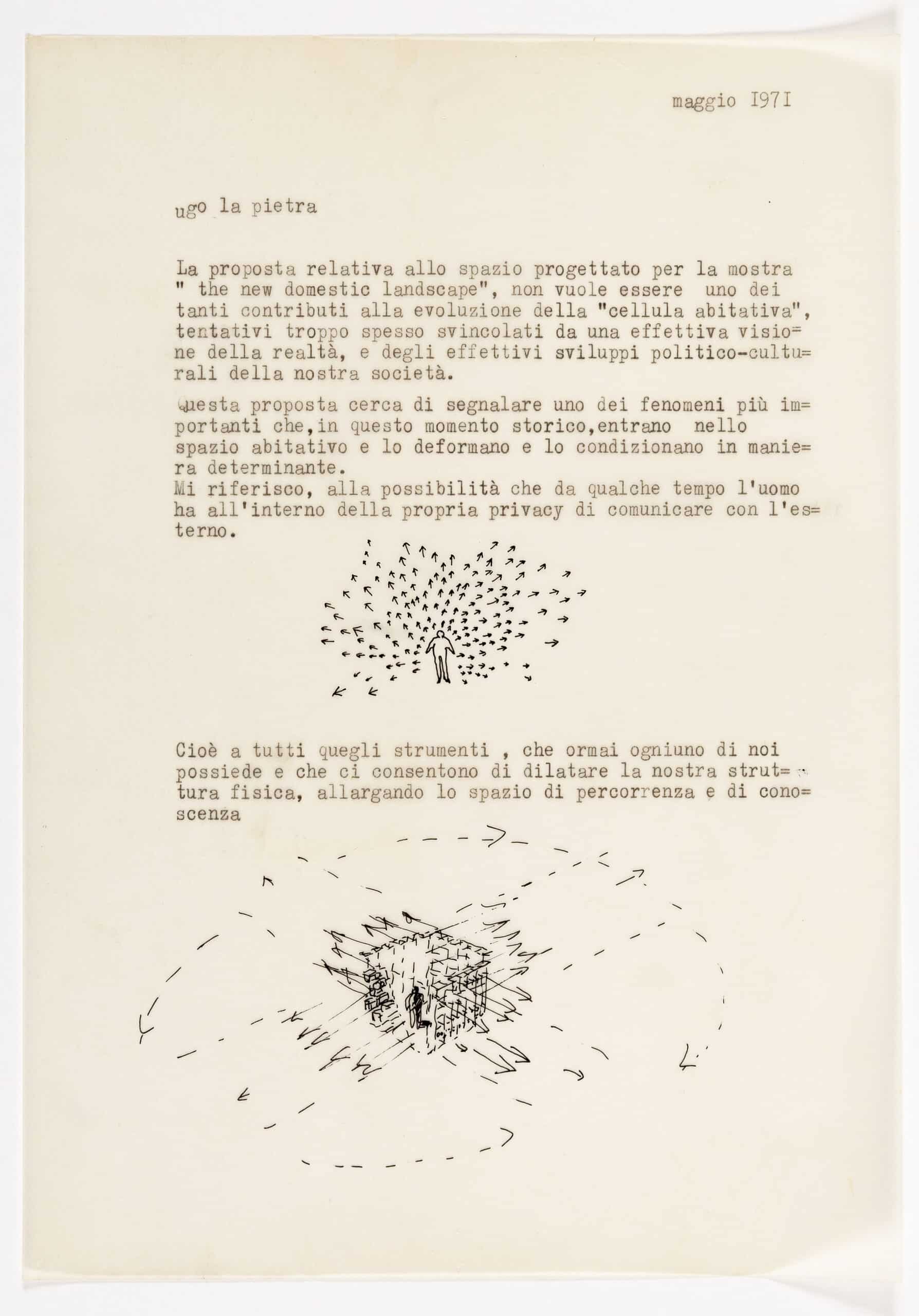

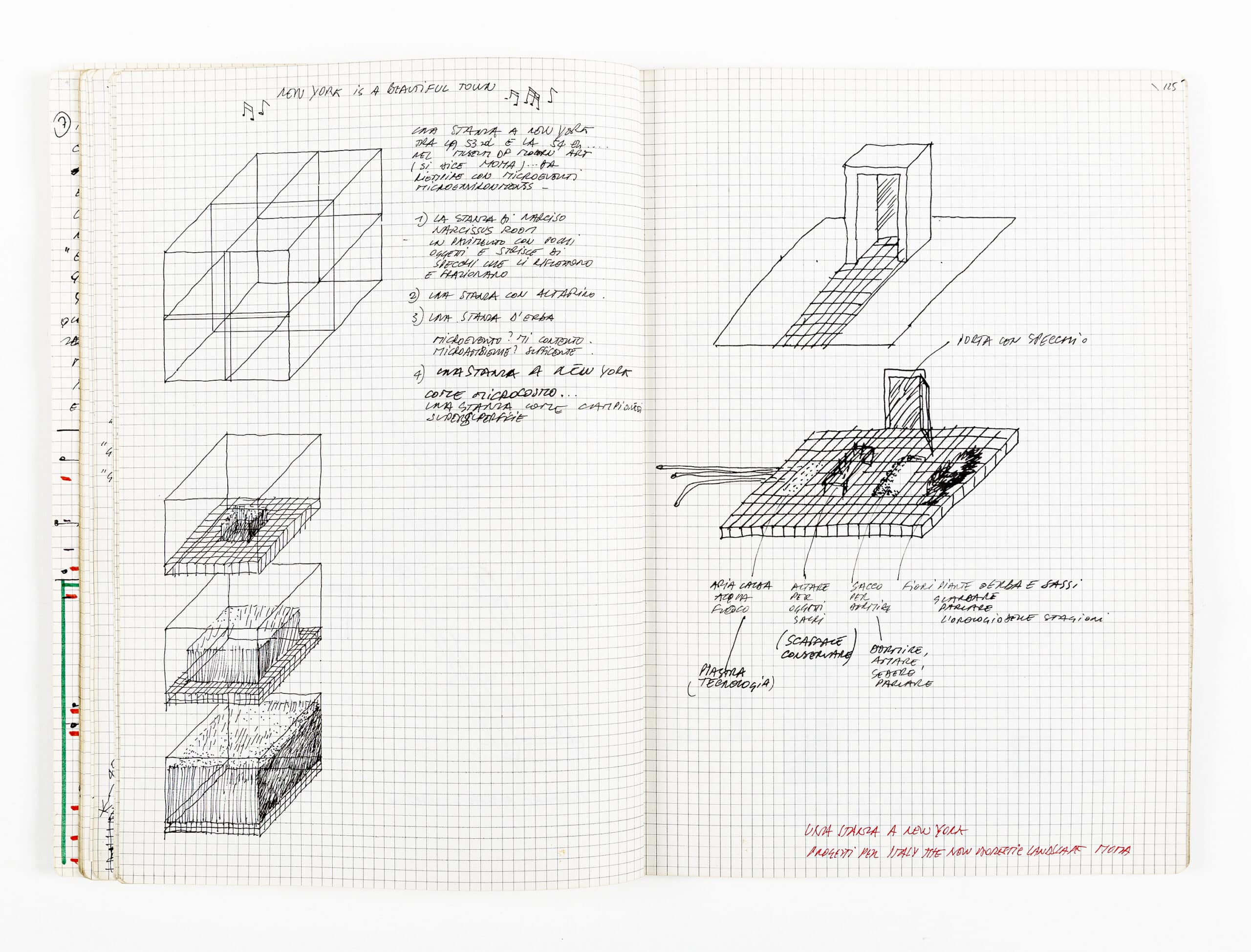

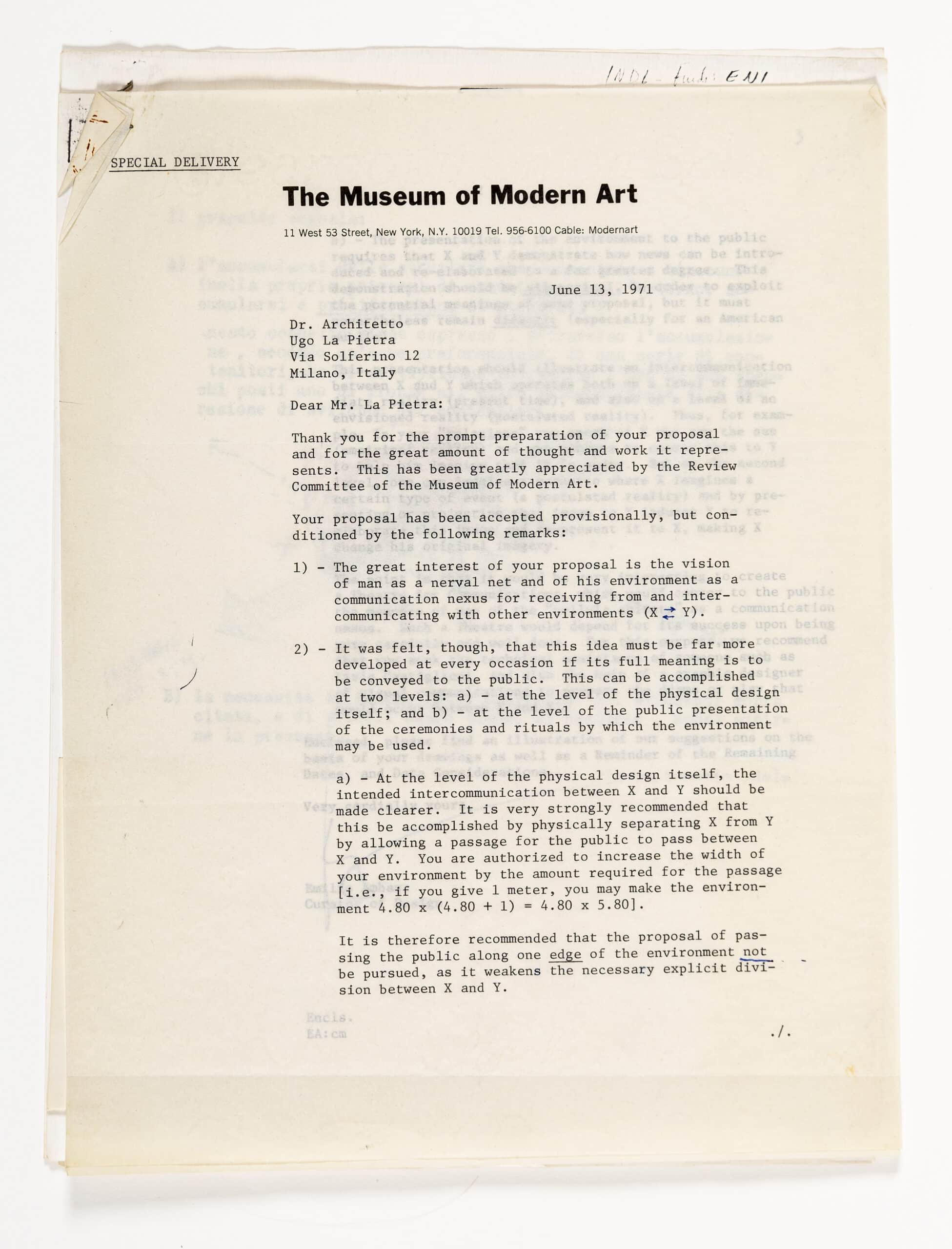

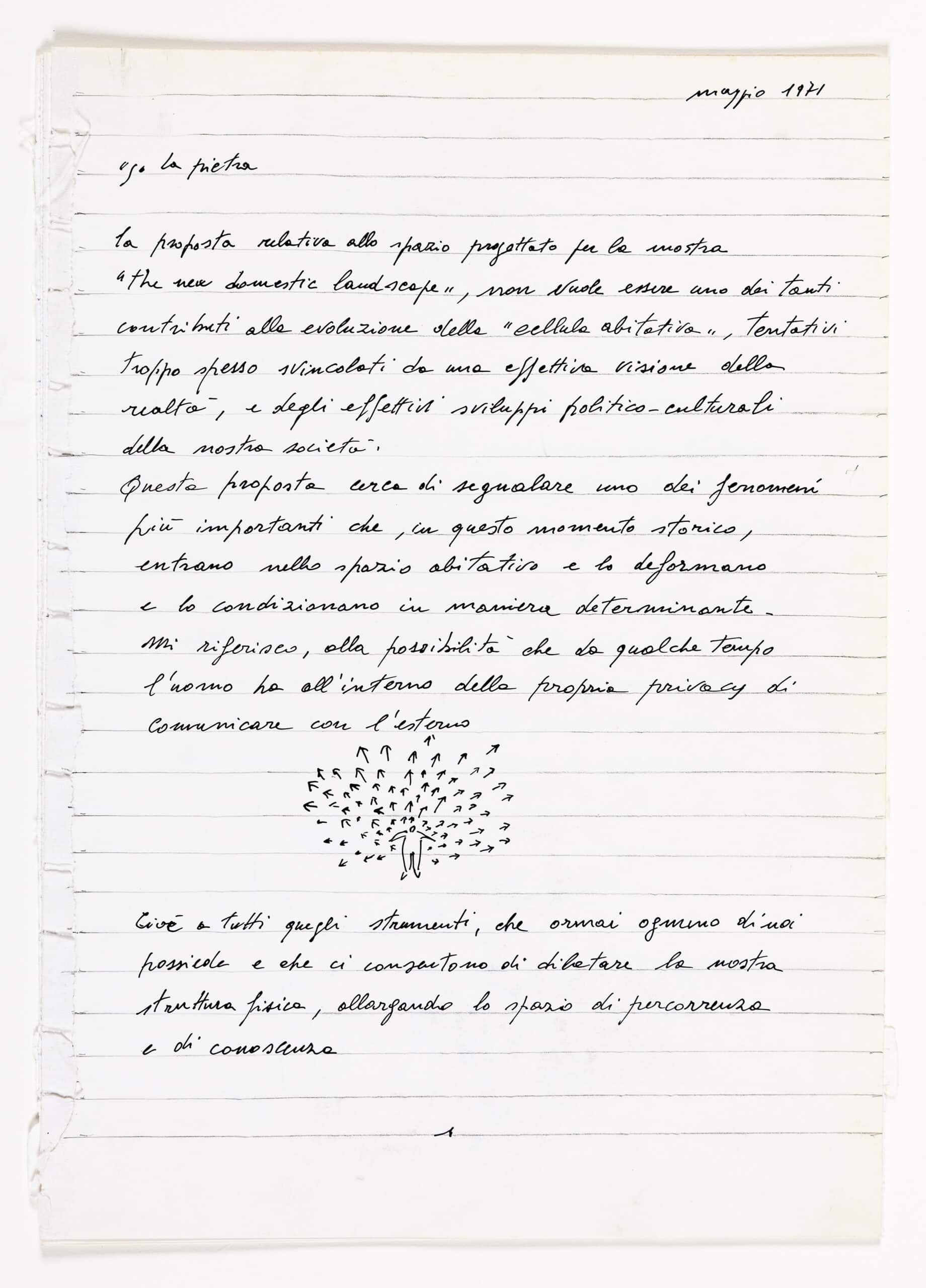

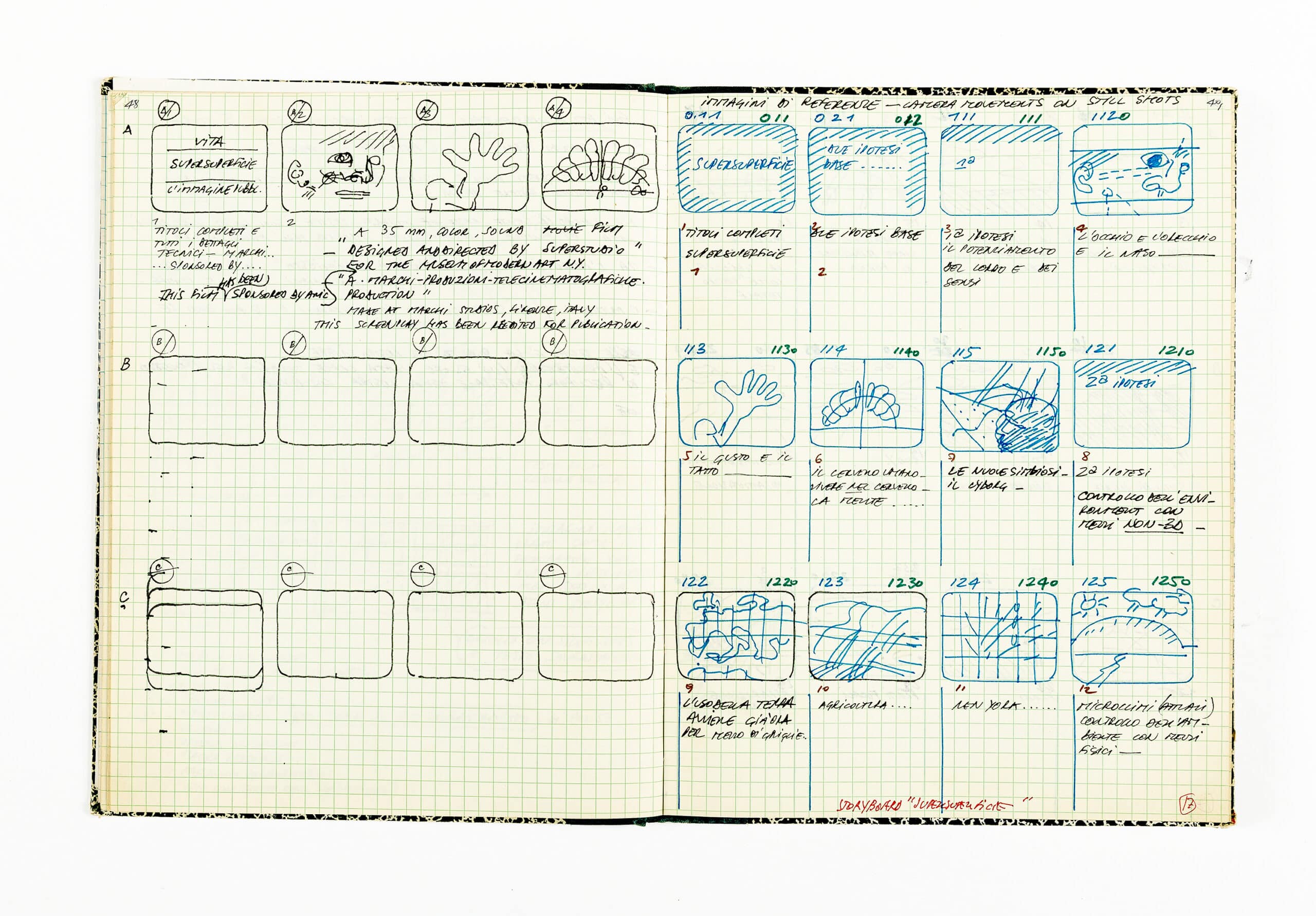

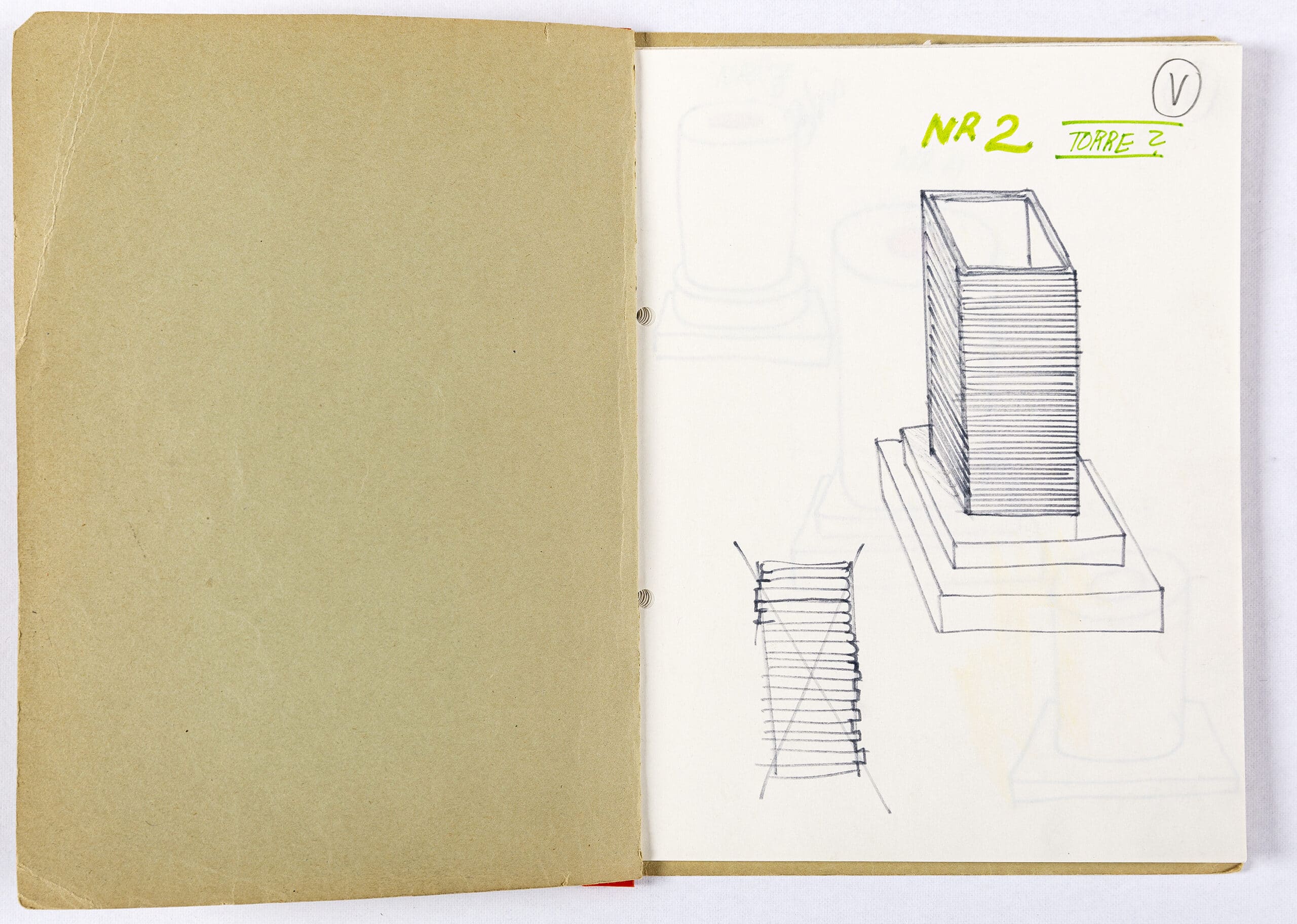

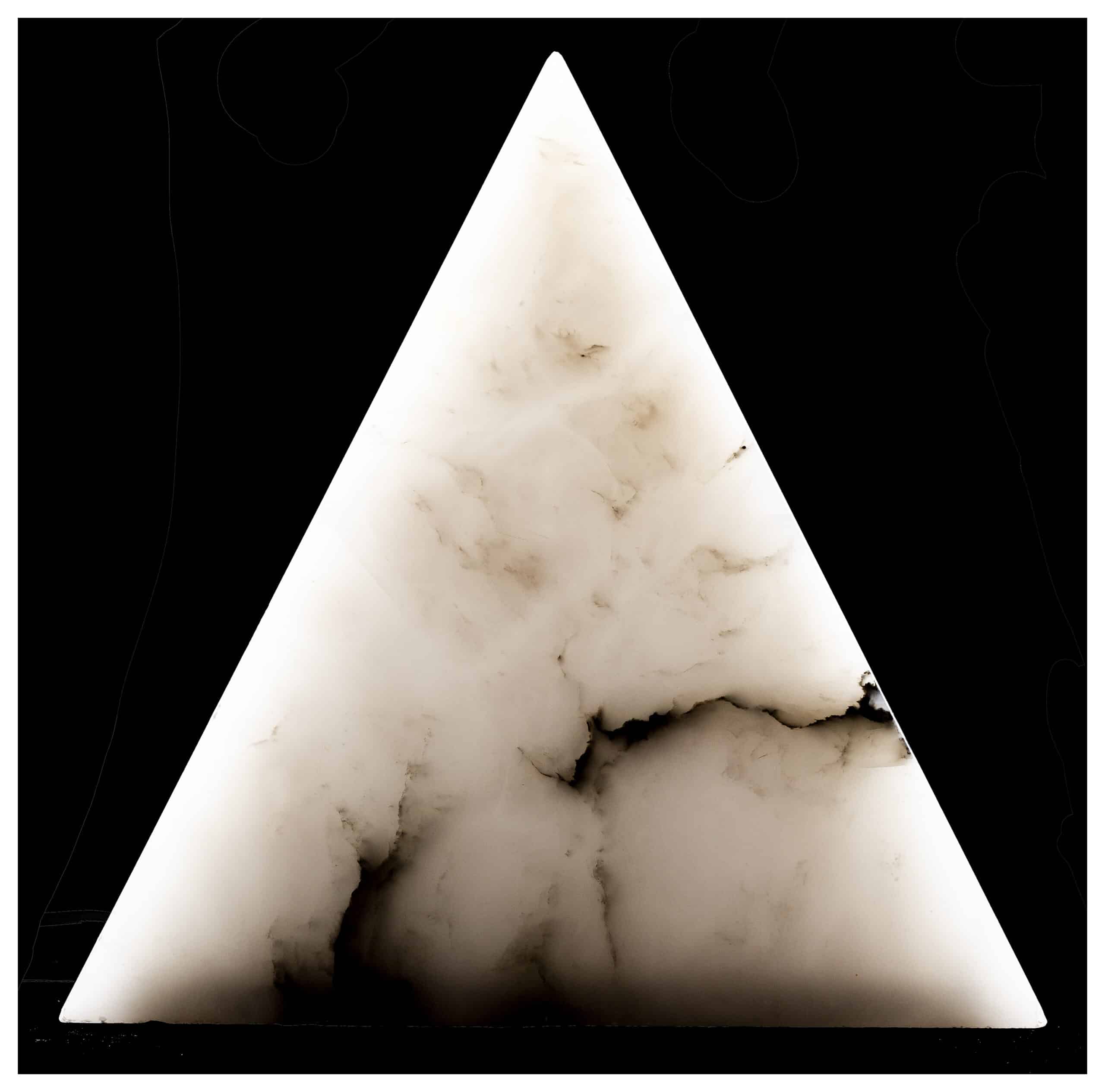

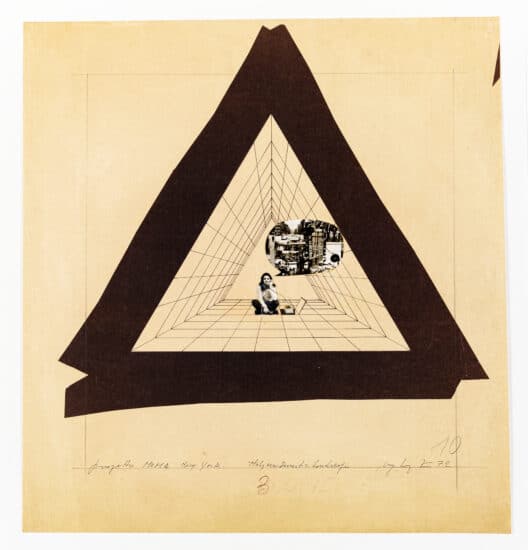

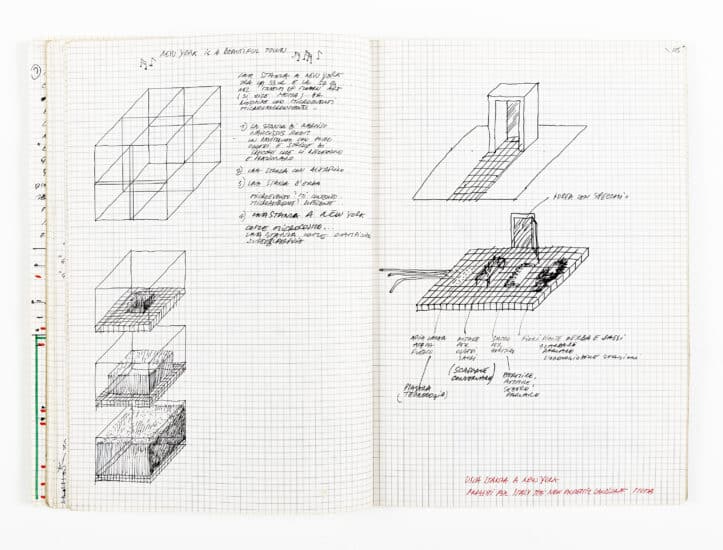

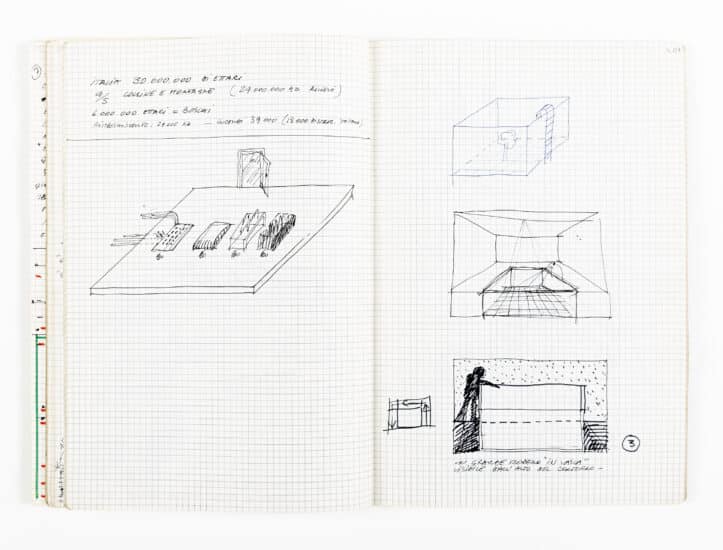

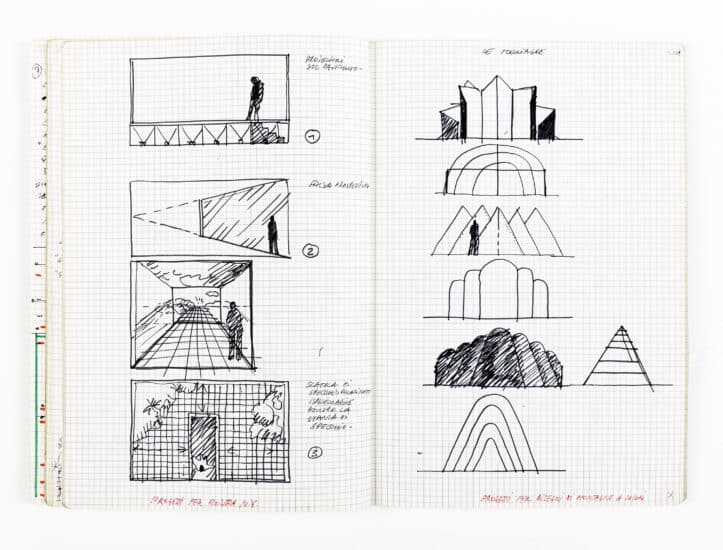

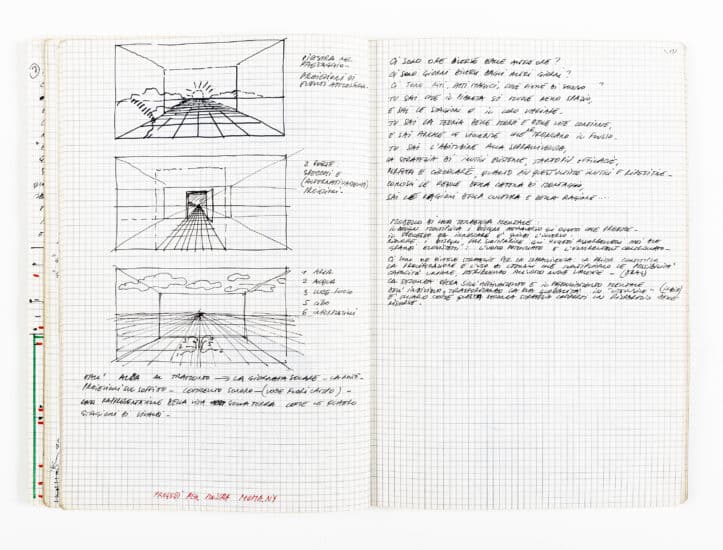

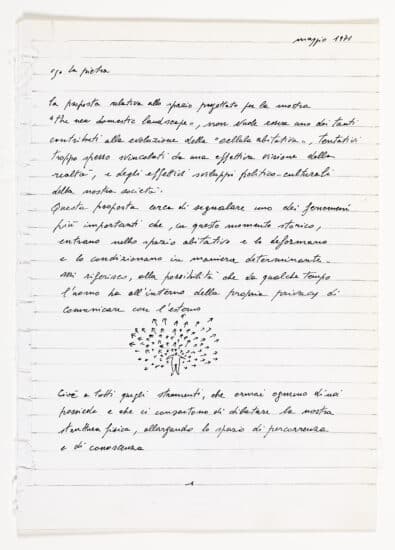

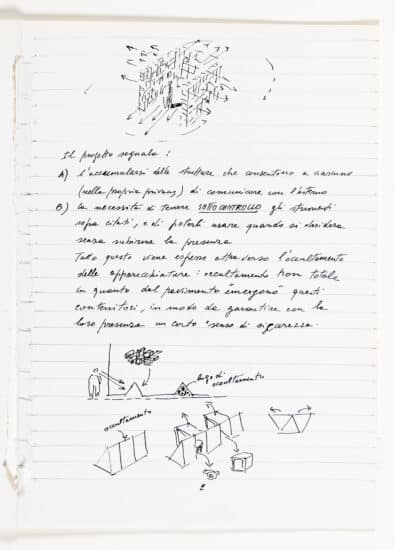

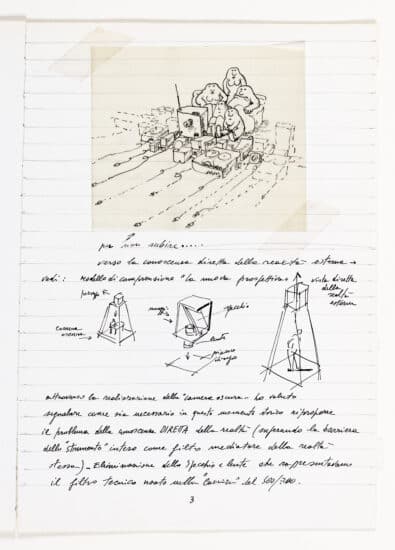

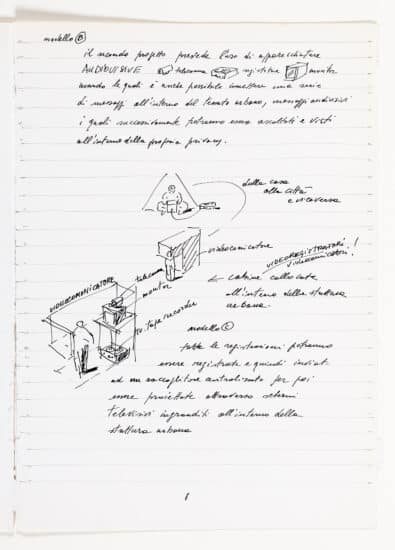

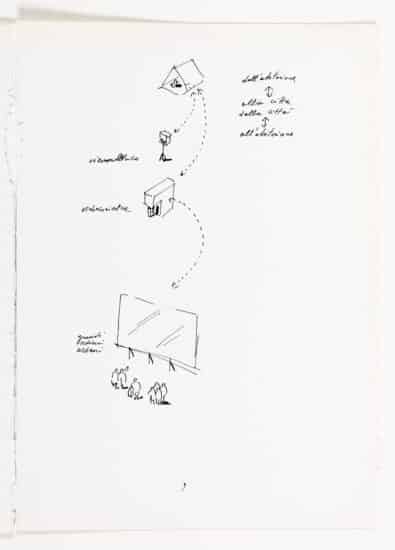

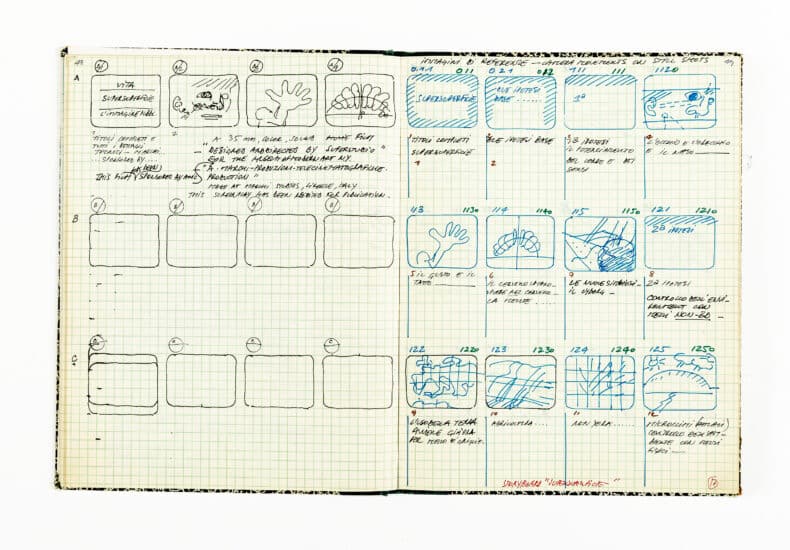

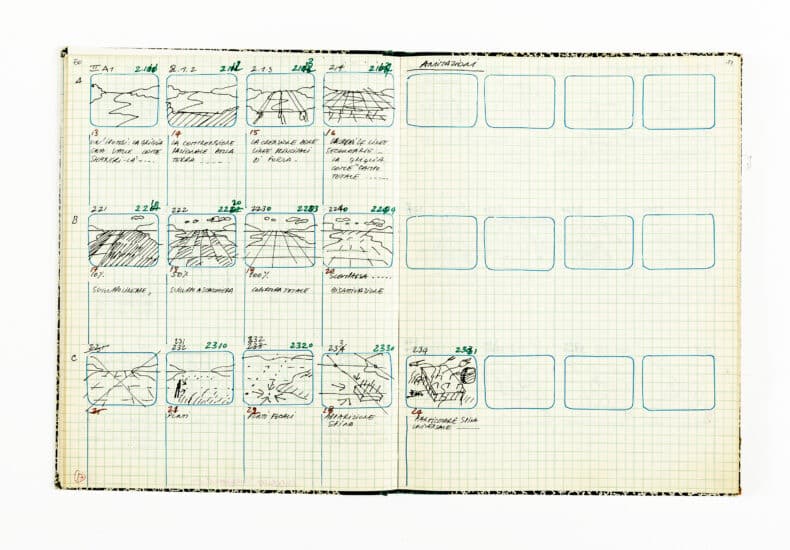

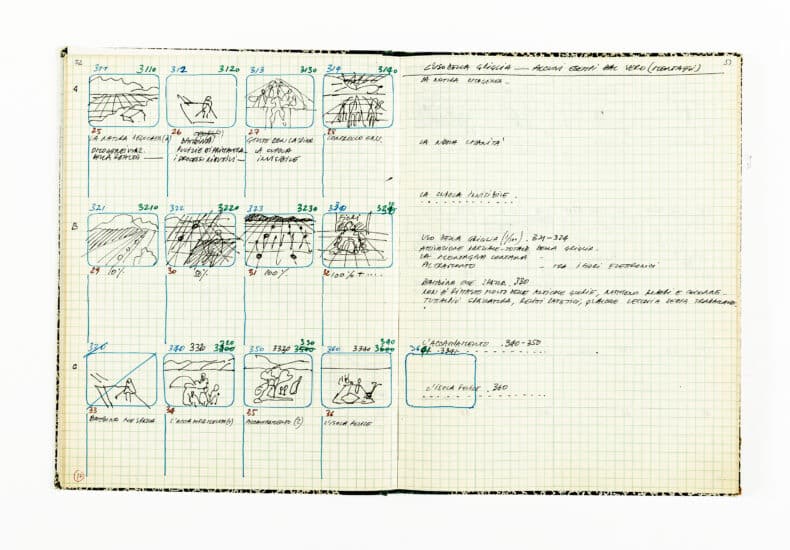

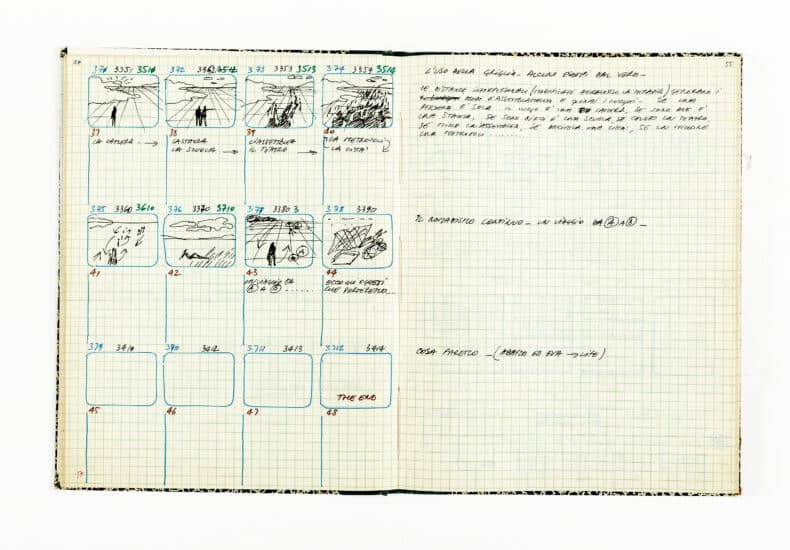

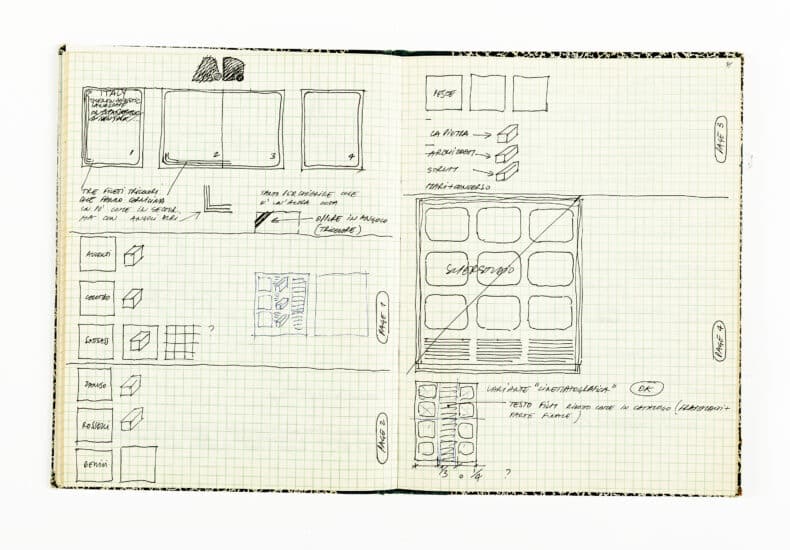

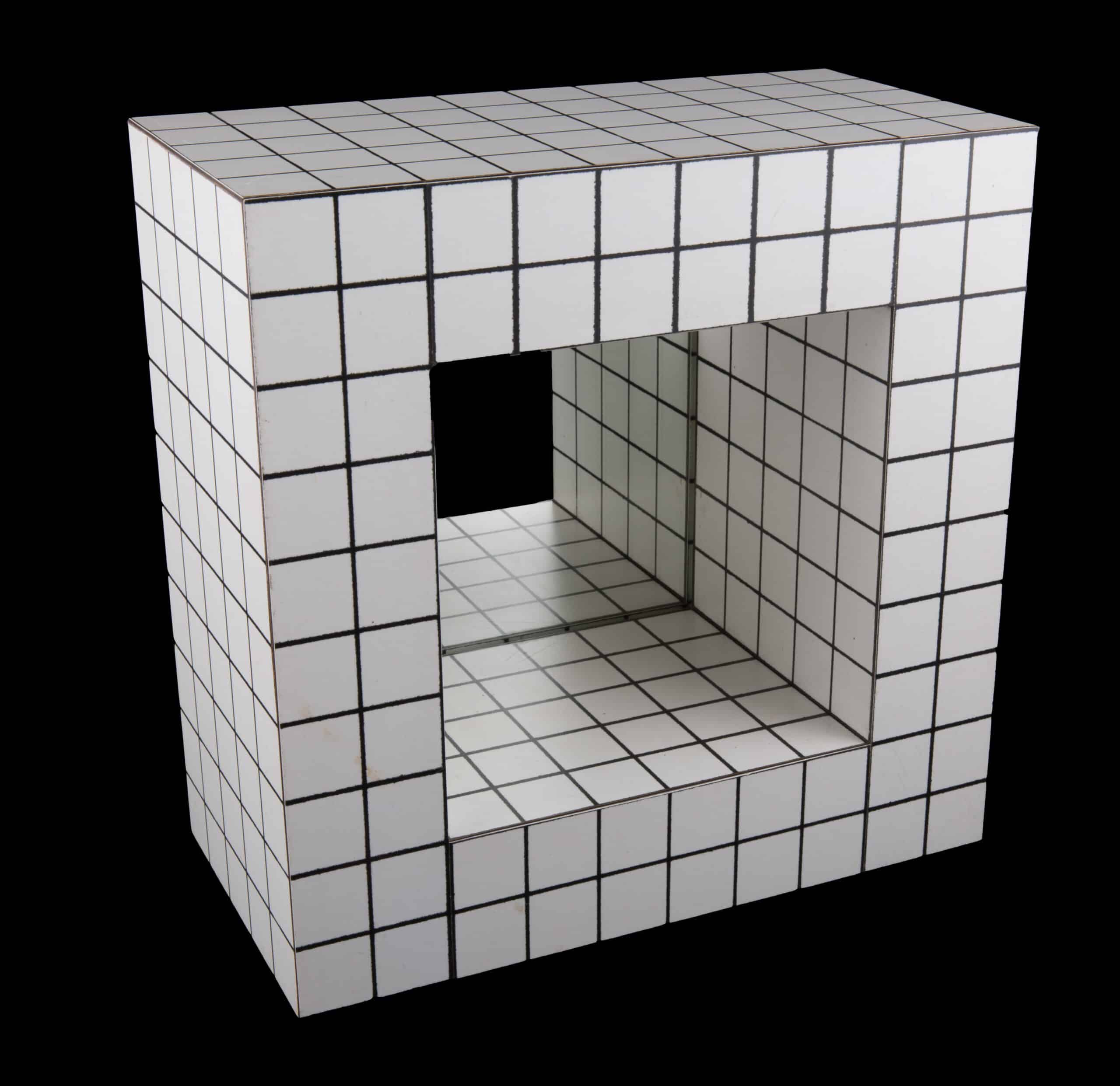

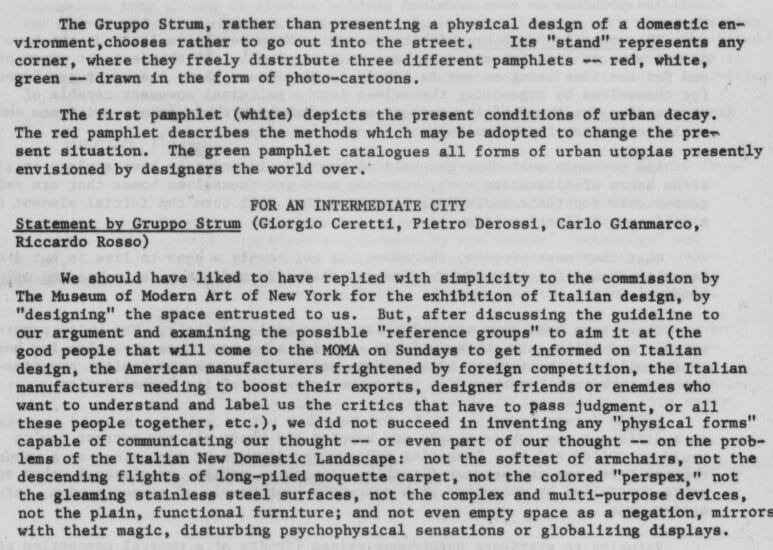

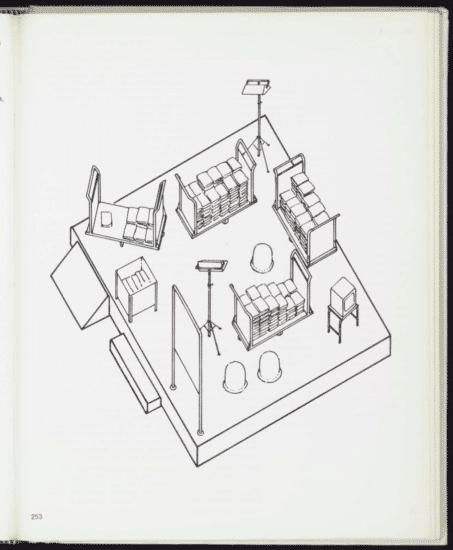

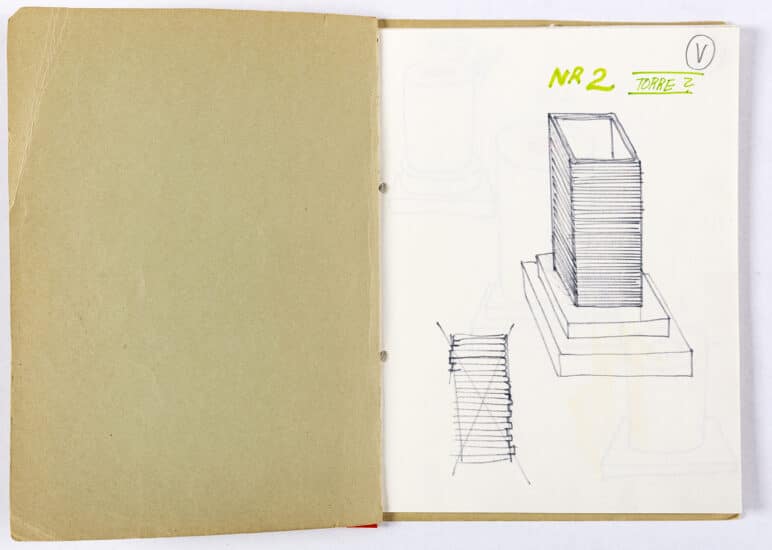

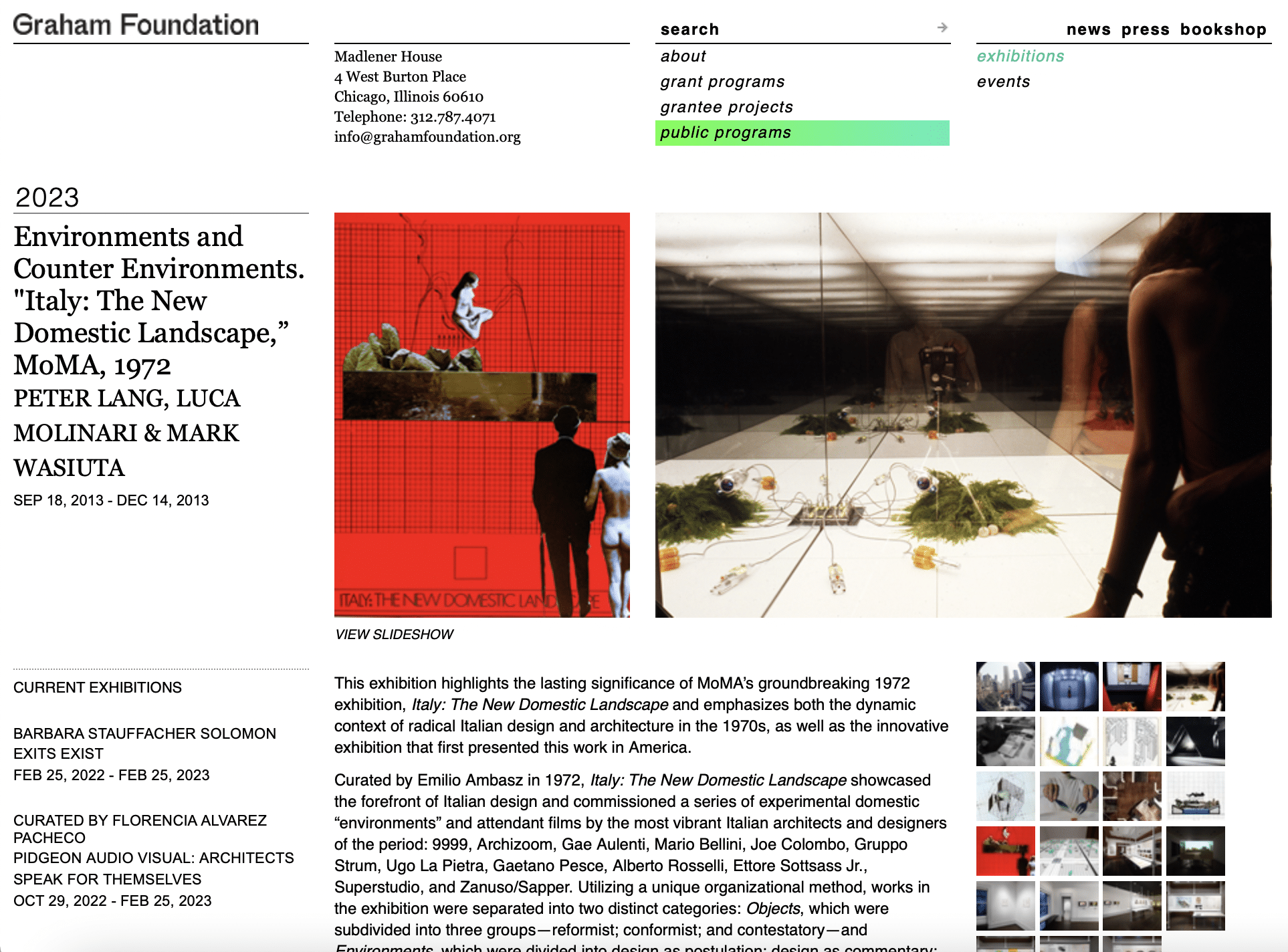

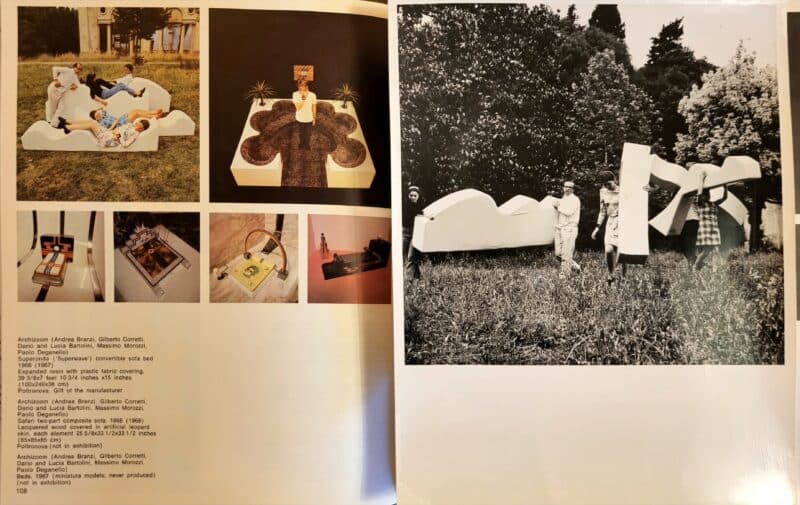

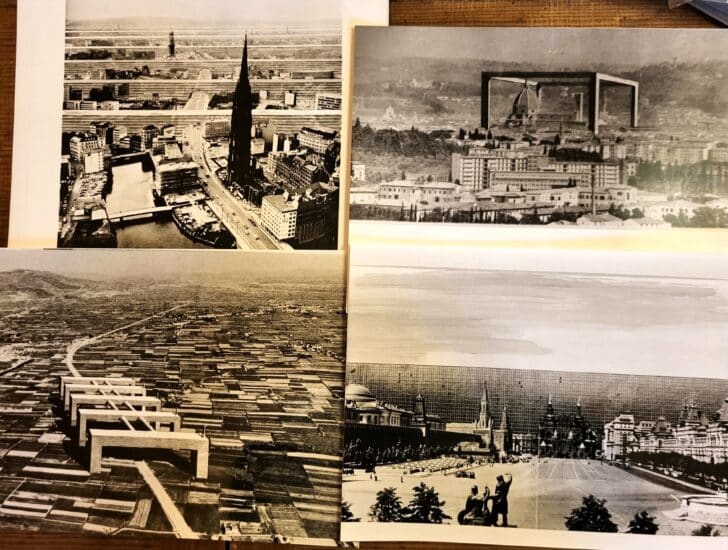

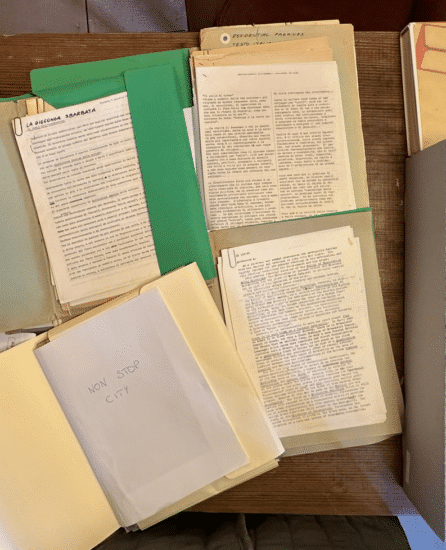

Late last year Emilio Ambasz offered us a fascinating text in which he reflects on ‘Italy, The New Domestic Landscape’, the seminal exhibition he curated in 1972 for MoMA. We have taken his text as an invitation to informally bring together drawings and objects related both to the exhibition and to the radical practices who participated, all now in the collection at Drawing Matter.

Emilo Ambasz: Looking back to see ahead

Starting in 1969 I originated a project culminating in 1972 at the Museum of Modern Art in New York as an exhibition entitled ‘Italy, the New Domestic Landscape’. This collection of objects and interiors illustrated the remarkable design vitality that had emerged in Italy. The exhibition... Continue Reading

Emilo Ambasz: Looking back to see ahead

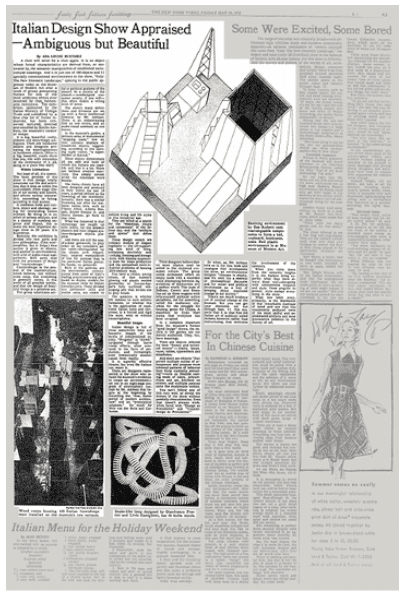

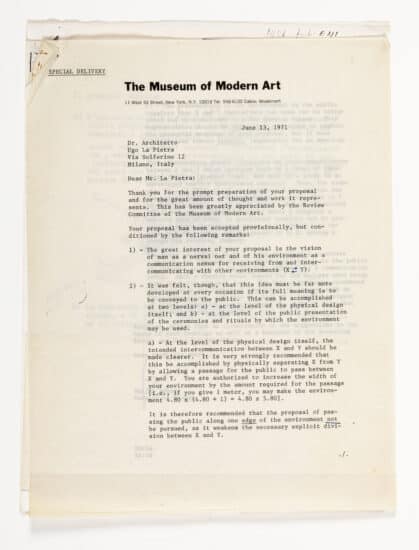

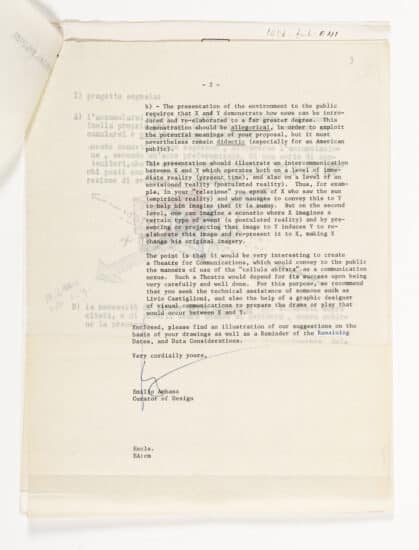

Starting in 1969 I originated a project culminating in 1972 at the Museum of Modern Art in New York as an exhibition entitled ‘Italy, the New Domestic Landscape’. This collection of objects and interiors illustrated the remarkable design vitality that had emerged in Italy. The exhibition was to leave a deep and pervasive imprint upon the perception of design in the USA. For the first time, Americans were invited to regard design not only as a product of the creative intelligence, but also as an exercise of the critical imagination. Visitors were to realise that design in general, and Italian design in particular, meant more than simply creating objects to satisfy functional and emotional needs: the processes and products of design could themselves be used to offer critical commentary, on us individually and upon our society.

The exhibition sent shock waves through the community of American designers. Here they found themselves confronting another breed of creator, one unafraid of curves and taking unabashed delight in the sensual attributes of the materials and textures he or she used. For many American and North European designers, sternly trained in the Bauhausian tradition of deductive analysis, strict functionalism and rigorous pragmatism, the flair and panache of the Italian designers were little less than offensive. The fabric of their professional repressions was so insidiously torn open by the creations of their Italian counterparts that they seemed ready to file a writ of complaint against Italian Design for a) having created beautiful objects in complete disregard of all prevailing rules; b) shamelessly seducing the public with these products; and what was even worse, c) having seduced the American designers themselves.

Today we find that Italian design has spawned a number of gifted American, European, South American and Oriental offspring. Like their Italian colleagues of yore, these new generation of designers have grown fonder of, and increasingly dexterous with, colours, curves, patterns and textures. No longer the unbending seekers of eternal truths after their Bauhausian ancestors, many designers have learned to make peace with the ephemeral. Design, once perceived as yet another method for redemption through sensory deprivation, had begun to open up its tightly closed fist to embrace fashion and caress ornament. Thus, a new type of designer, one who takes joy in the exercise of his or her stylistic gifts, has emerged. Perhaps in 2022, fifty years after ‘The New Domestic Landscape’, we shall be able to determine whether the debt to Italian design is deeper than, and goes beyond, mere resemblance.

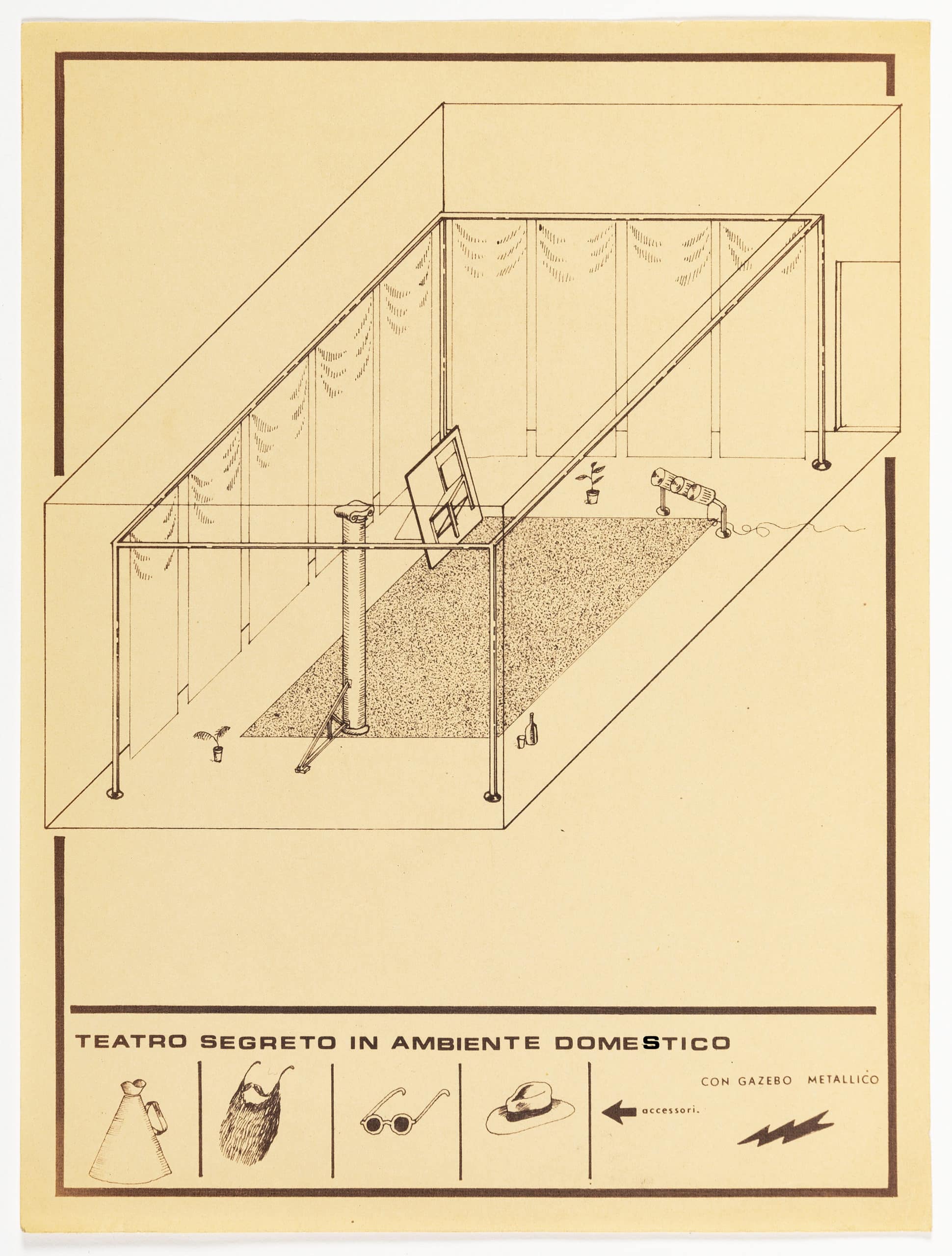

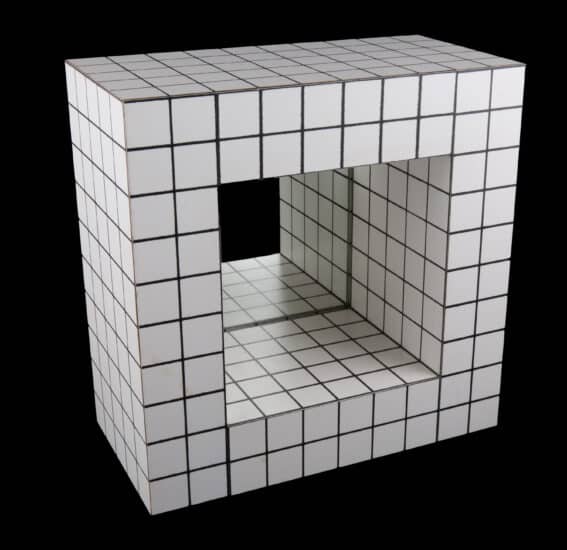

Perceptive visitors may have noticed that the exhibition’s diverse optics (product design, social, and artistic) utilised to analyse the Italian design phenomena had also amalgamated a sub-rosa anthropological lens. Neither would have escaped them that the exhibition made evident what has nowadays become a domineering intellectual concern of designers: the design of behaviours. The heralding of such pursuits may be bestowed, as an example, on one of the shown products: Il Sacco (a. k. a. The Beanbag). As opposed to a standard chair, which imposes a rather fixed position and behaviour on the part of the sitter vis-à-vis itself and those facing him/her, the Sacco is behaviourally indeterminate. Designed by Piero Gatti, Cesare Paolini and Franco Teodoro, it is an early example of a chair with no fixed shape, as the shape of the object must be set by the user.

As we look upon Italian production today, we realise that the Museum of Modern Art’s 1972 show clearly marked a high point of Italian design as a freewheeling creative process, realising that the classical ambivalences of design remain still valid today: conformism and/or reformism; idealistic and/or reformist; integrated design and/or alternative design are still prevailing. All too understandably, the former constitutes the great part of Italian design’s production. A considerable portion of ongoing Italian design activity has concentrated upon improving the quality of established models, with much attention given, for example, to how different materials can be gracefully juxtaposed and skilfully combined; how component elements can be well built and better joined; how the quality of colours, patterns and textures can be subtly enhanced.

Many products of Italian design have, since 1972, traveled from the Museum to the Marketplace. Once, these objects were fancied harbingers of upcoming social change; today, they have become fixtures of society. If they have not fulfilled all the utopian promises of ‘68, they have nevertheless enriched and improved the quality of our daily existence. If these objects have fallen short of offering path markers for our long voyage to a brighter, better tomorrow, they have happily performed a more modest role as pleasant companions in our daily travails.

Italian products of the last half century have given pleasure, performed faithfully, and, why not say it, they have tickled our fancy and flattered our pride. They have, in some small but true way, helped us through the day and soothingly seen us past the night. Handsome and wholesome, these products have served us well. If they have sometimes failed to move our hearts, they have always touched our minds and alerted our senses. What greater badge of honourable service can be bestowed upon an object and on the culture that created it?