Genius loci

This text was first published in French in d’a | d’architectures (no 322,11 December 2024) as a review of the exhibition Trompe-l’oeil, from 1520 to the present day, which was on show at the Musée Marmottan Monet in Paris from 17 October 2024 to 2 March 2025.

*

It is difficult to distinguish between the artist, the architect, and the engineer in the Quattrocento. The exhibition Trompe-l’oeil, from 1520 to the present day, currently on show in Paris, provides an opportunity to revisit this playful practice of demystifying reality that constituted an artistic-scientific exercise of the Ponts et Chaussées in the 18th century.

Polymathy, or the talent to move indifferently between arts and sciences, was second nature to certain Quattrocento figures. Two figures are of interest here: the Florentines Brunelleschi and Paolo Uccello. The former demonstrated the perspectival process in public just steps away from his work on the dome of the Santa Maria del Fiore Cathedral in Florence. In 1425, this was not yet called a happening, but this process already combined art with technological innovation and theory with the tangible. The latter, a painter who asserted his scientific skills, prefigured digital modelling through a perfectly traced artefact: the mazzochio, a rigorous geometric construction with which he adorned some of the figures in his battle scenes.

It is under this artistic influence that the studiolo appeared, adorning certain Italian palaces. It was a space of about ten square meters for scholarly elites. The marquetry walls featured fake shelves with open shutters containing fake musical instruments and books. Among the many symbols was the intriguing mazzochio, placed on a flattened vertical bench. In a game of complicity with the viewer, the perspective is transformed into a trompe-l’oeil.

PERSPECTOPHILES

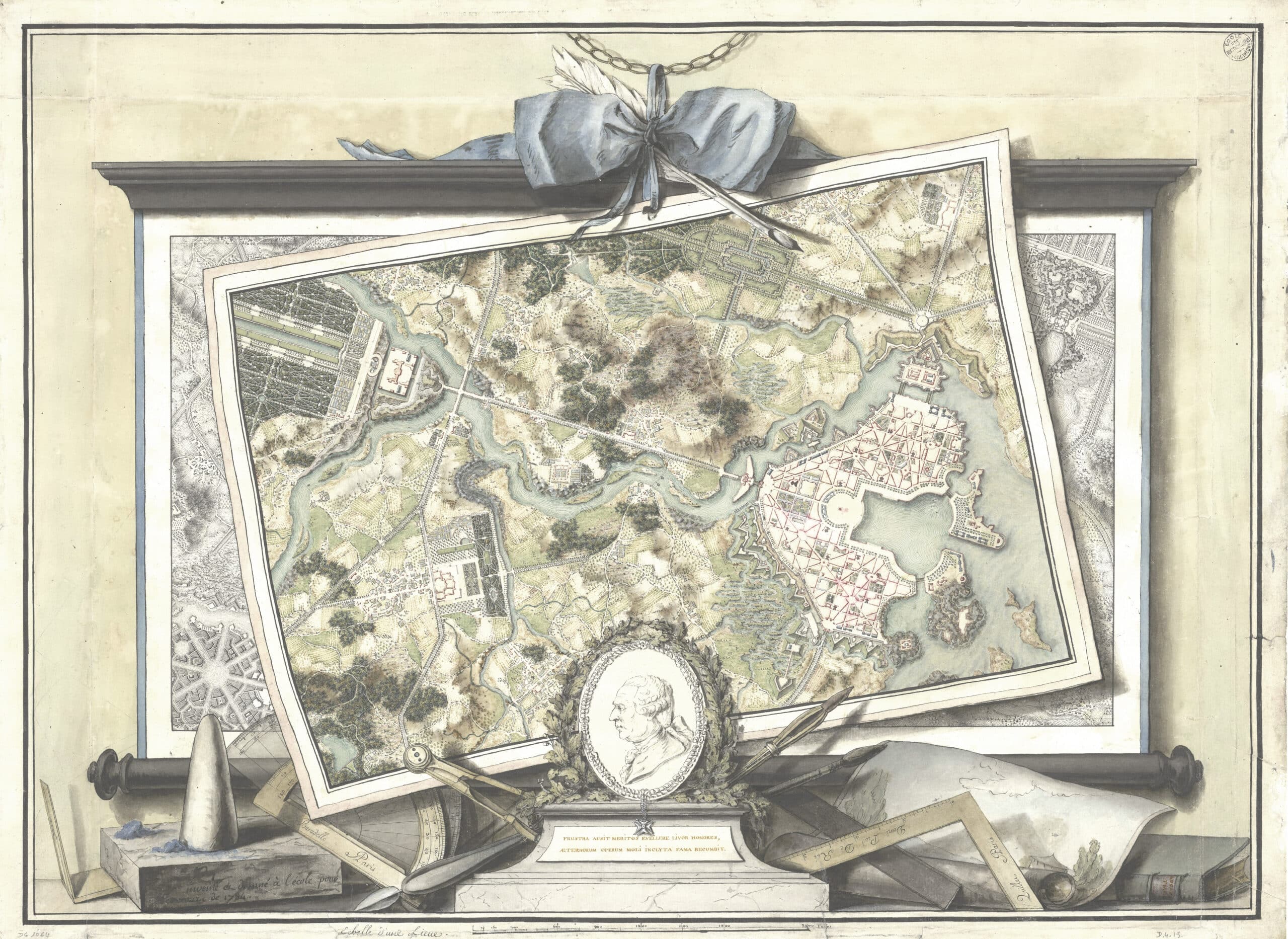

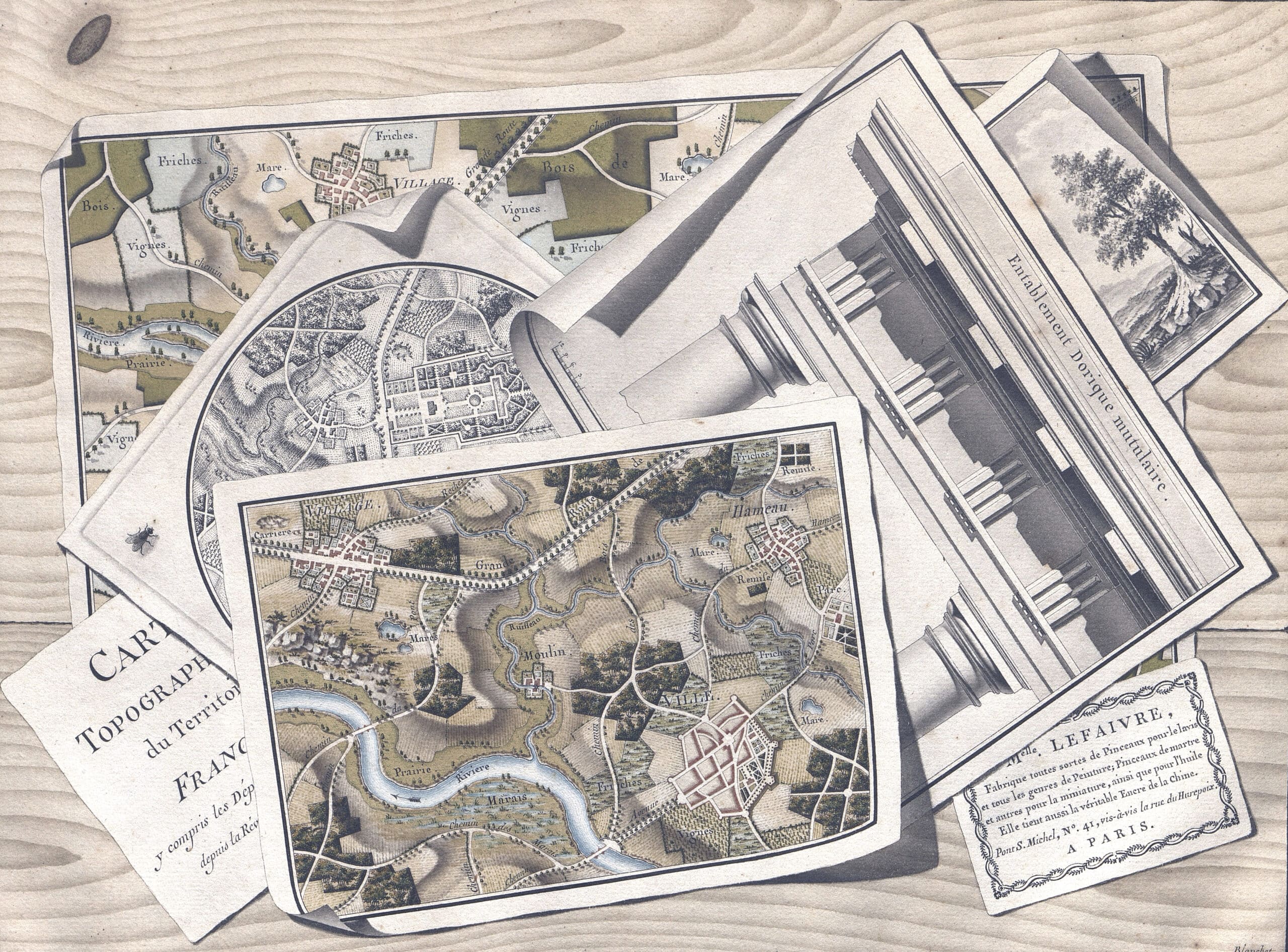

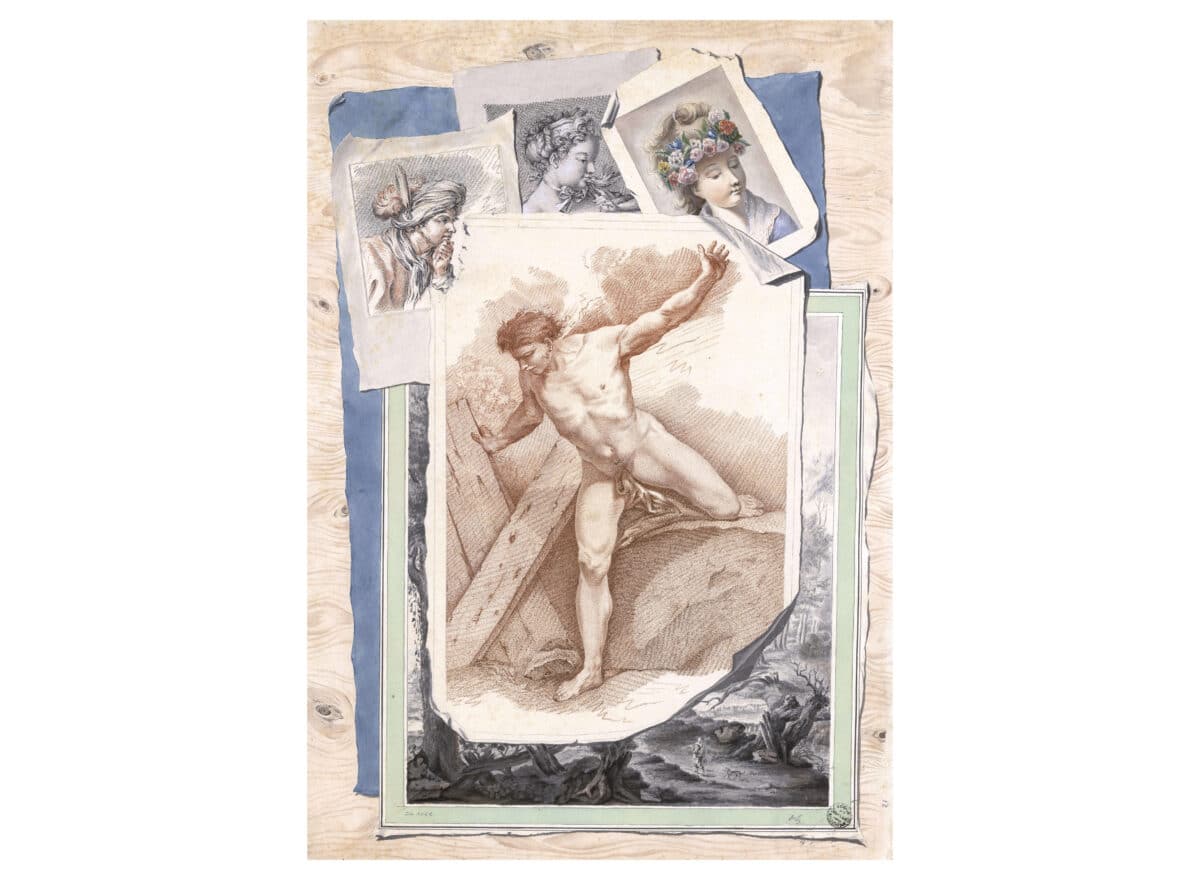

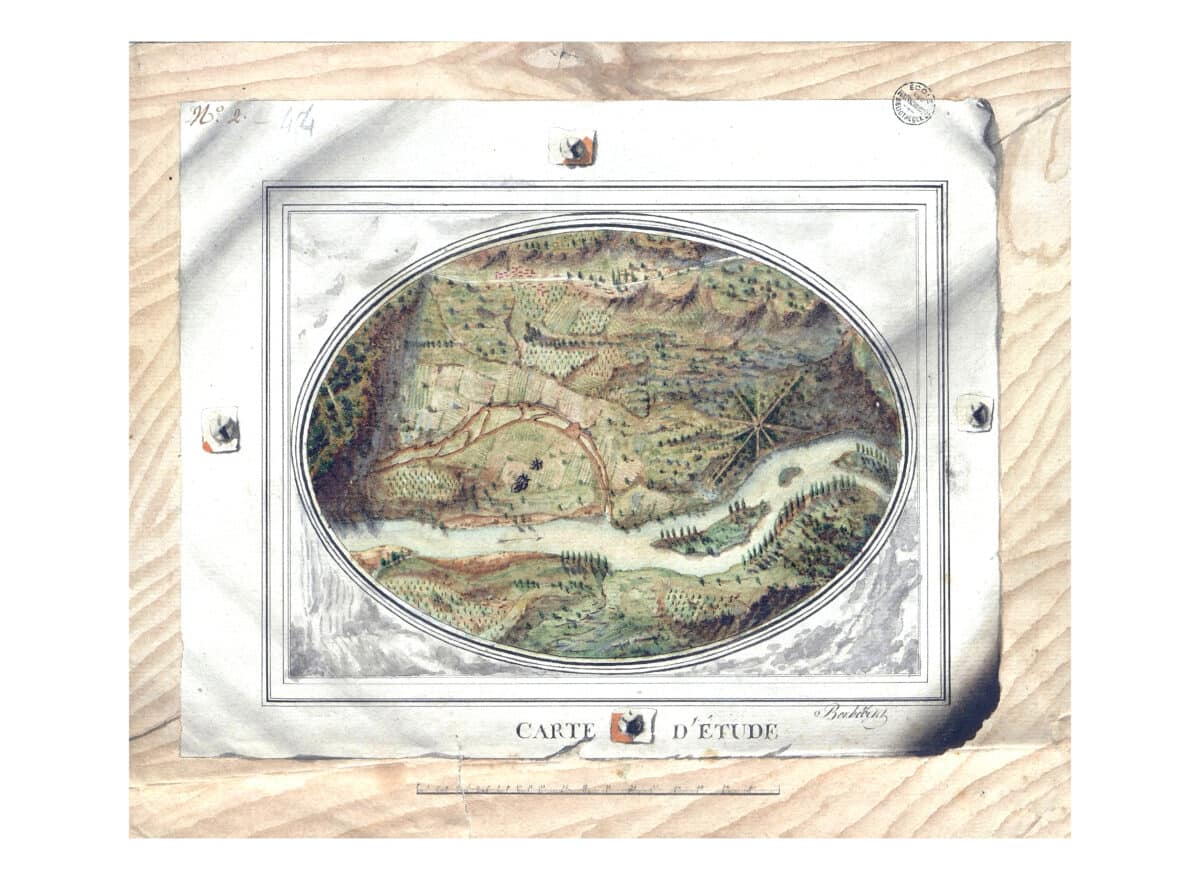

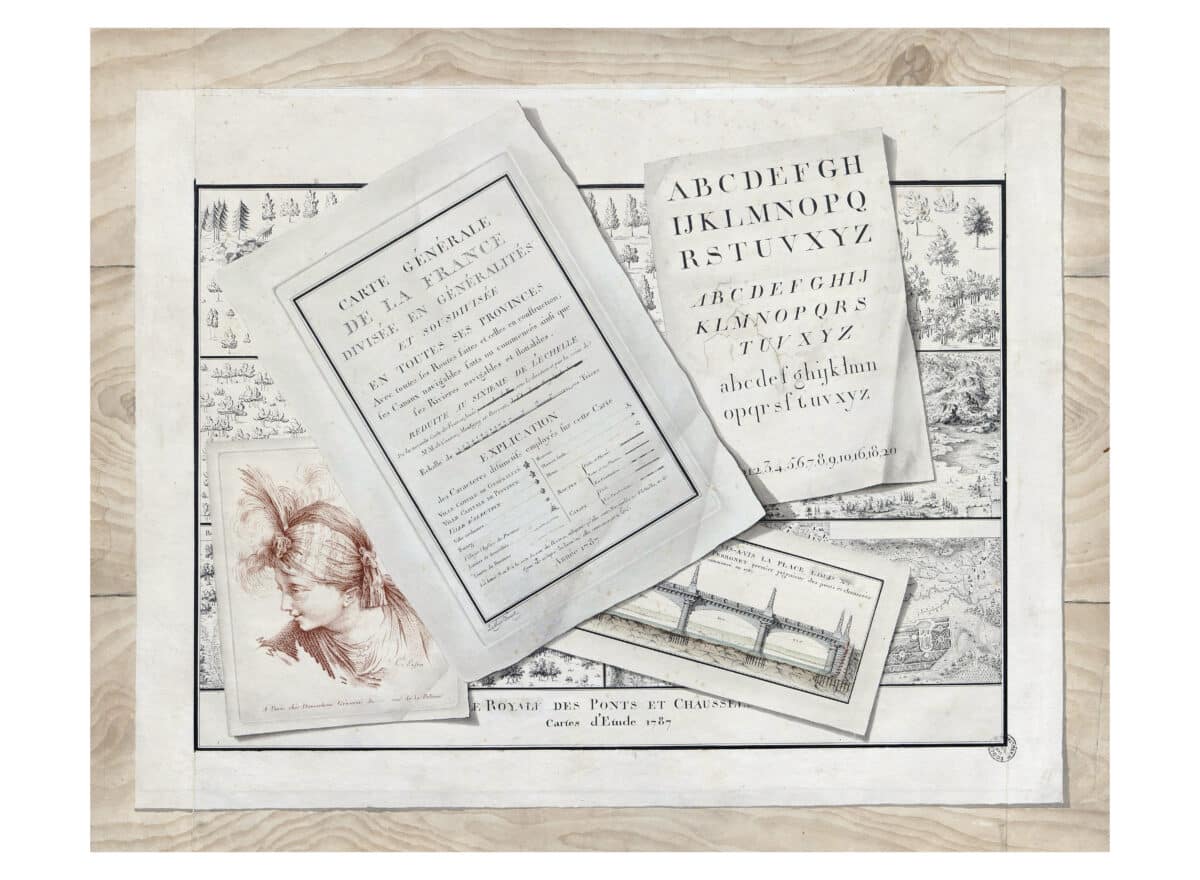

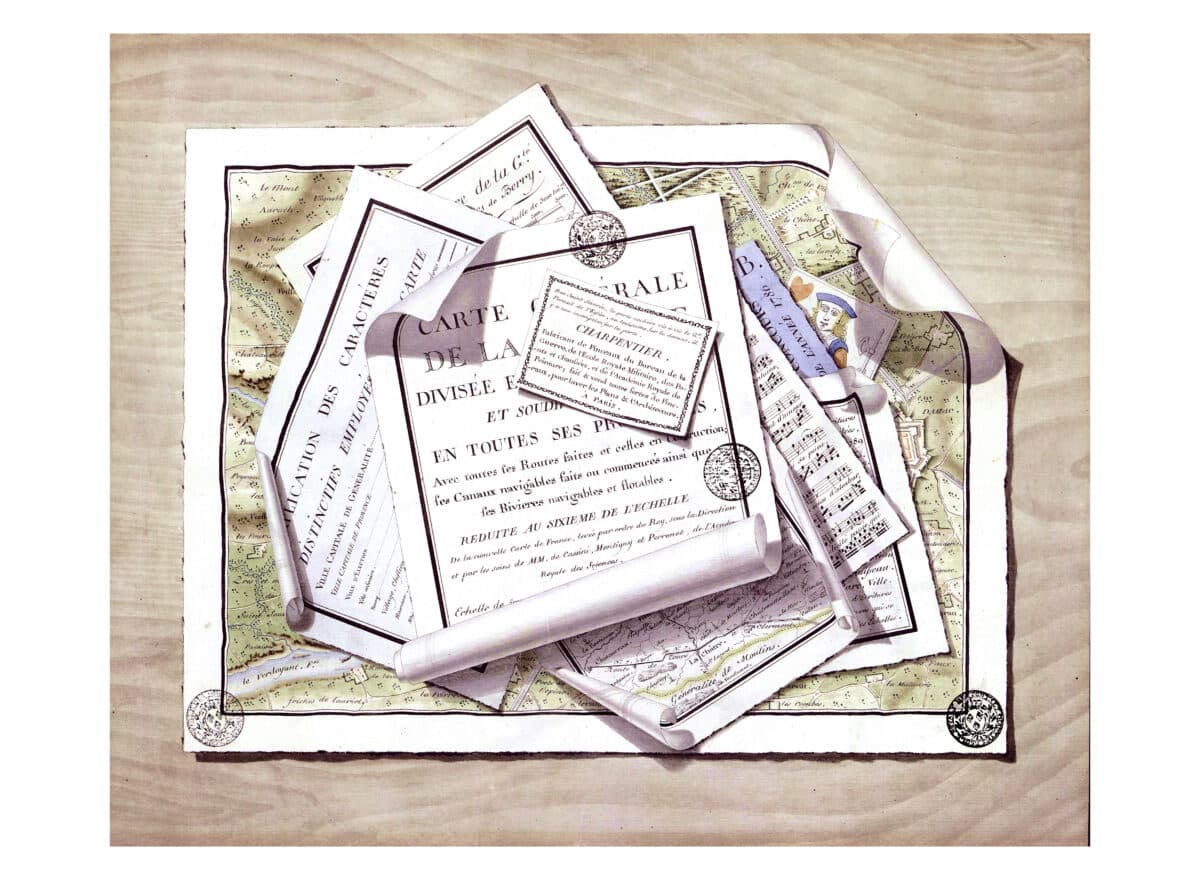

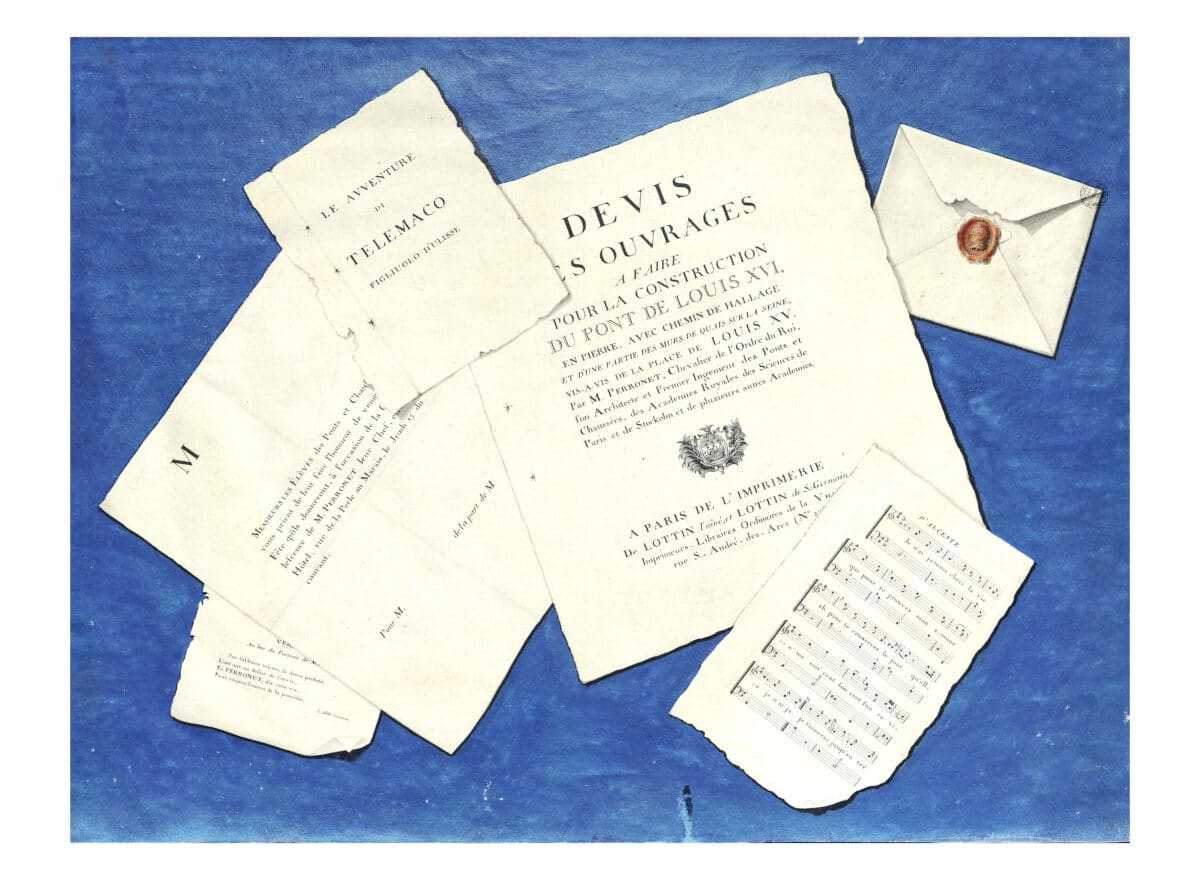

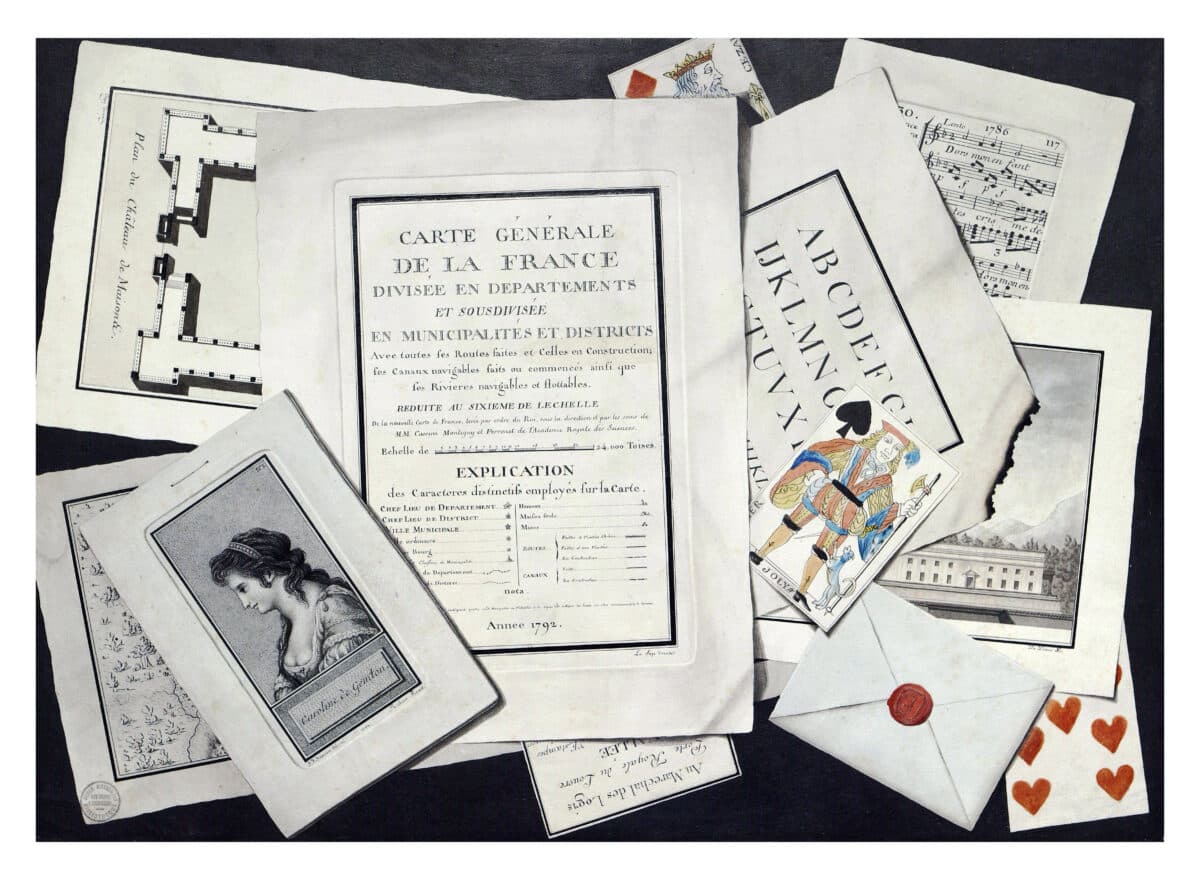

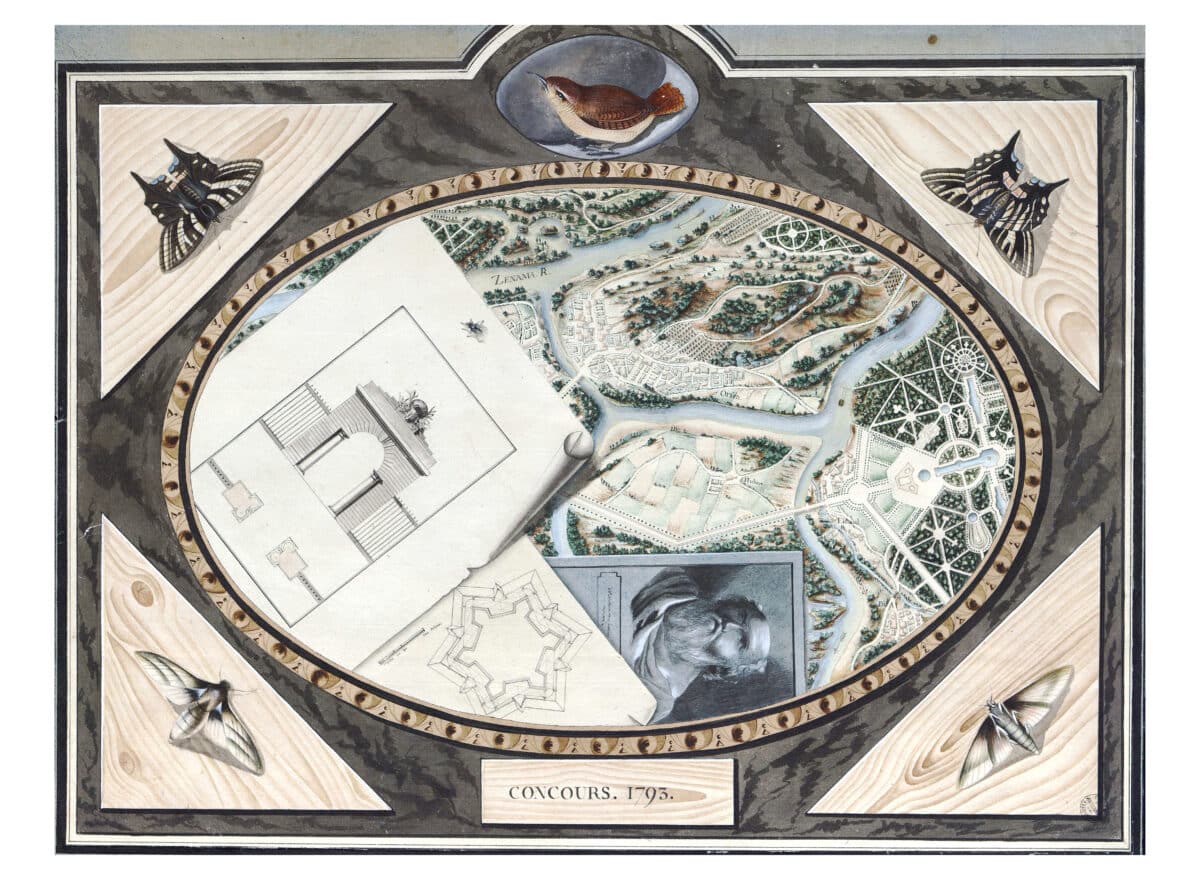

Trompe-l’oeil flourished in Europe, responding to specific conventions: breaking free from the frame and representing objects on a 1:1 scale. The genre was restricted to shallow depths and the play of contrasts and shadows. These images extend the theme of the cabinet of curiosities with low-relief artefacts: superimposed fake prints, creased or torn papers, medallions pinned to textured velvet or wooden backgrounds that the hand is tempted to touch. Pushed to its extreme, the ultimate illusion by the Flemish Cornelis Norbertus Gysbrechts depicts the back of a frame.

On a completely different level, this process would unfold its horizontal dimension in France thanks to the inventiveness of engineers and land planners. When the École des Ponts et Chaussées was founded in 1747, its first director, the architect of public works Jean-Rodolphe Perronet, defined the principles of a new pedagogy. In order to coordinate their actions and standardise their knowledge, future engineers trained each other and were assessed annually through a series of tests: mathematics, construction, stereotomy, essay, plan survey, theory and practice of levelling, surveying of building works, writing, and drawing.

THE MAP AND THE TERRITORY

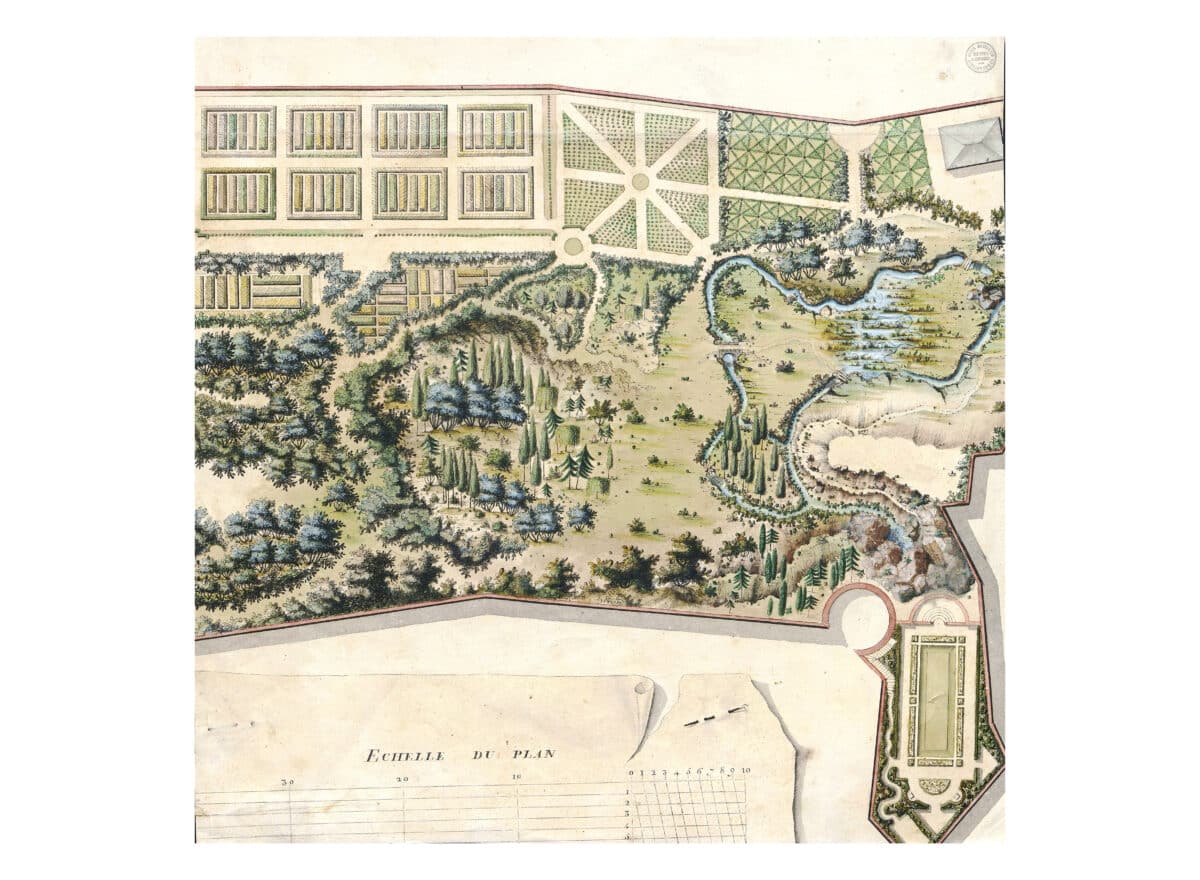

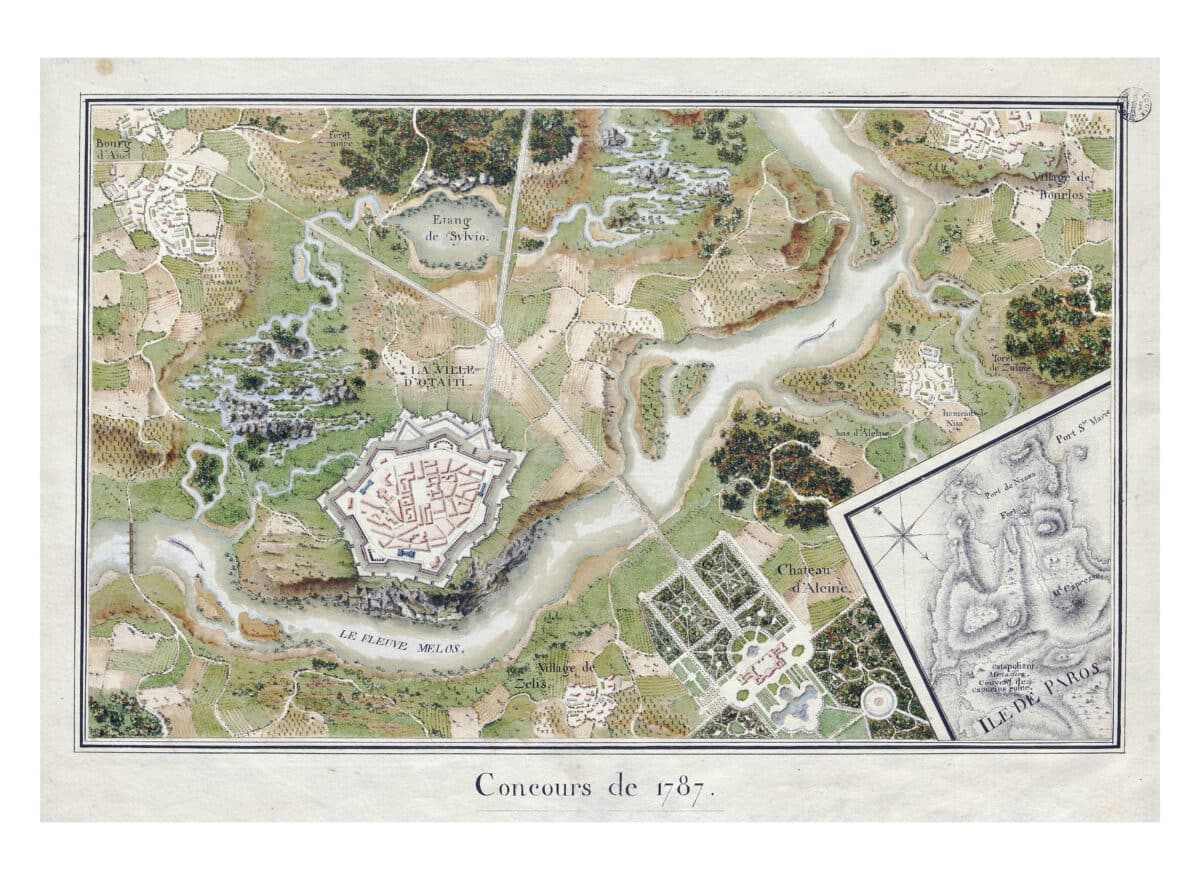

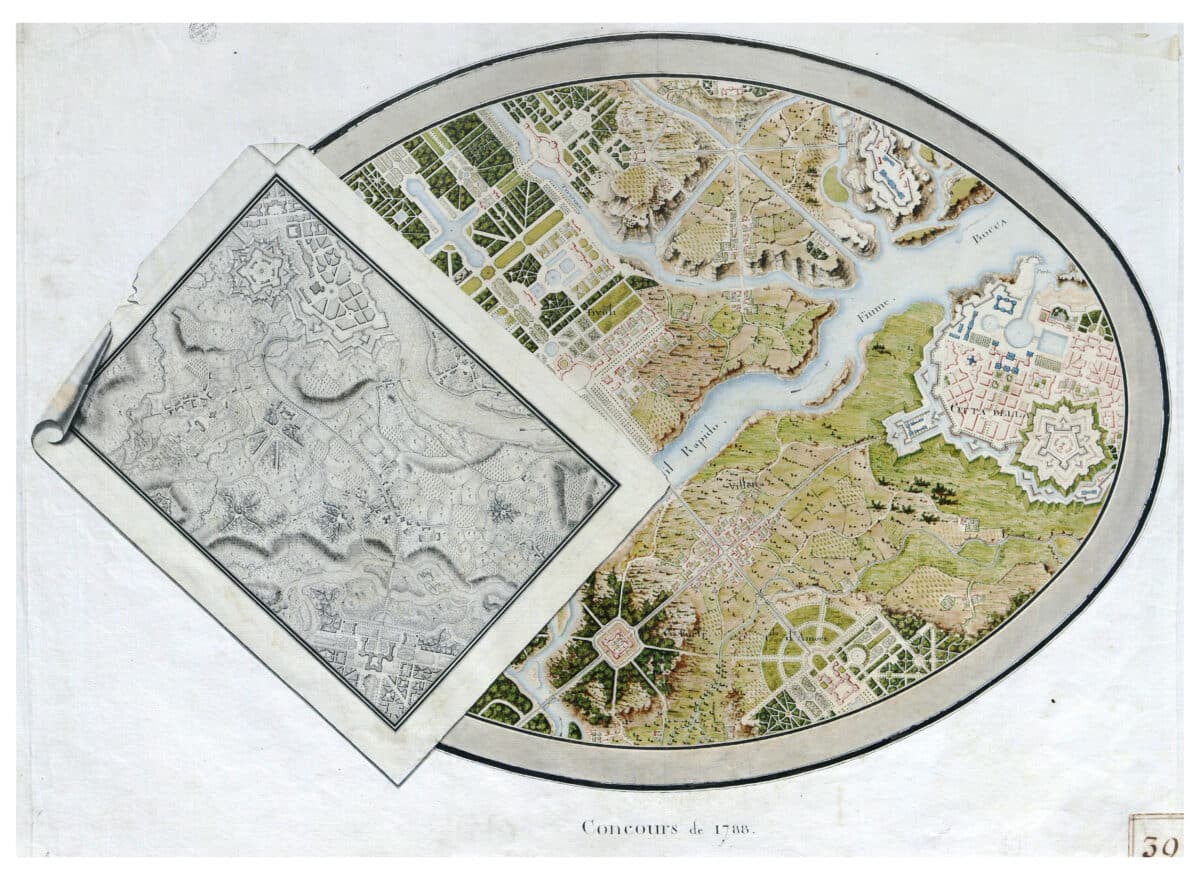

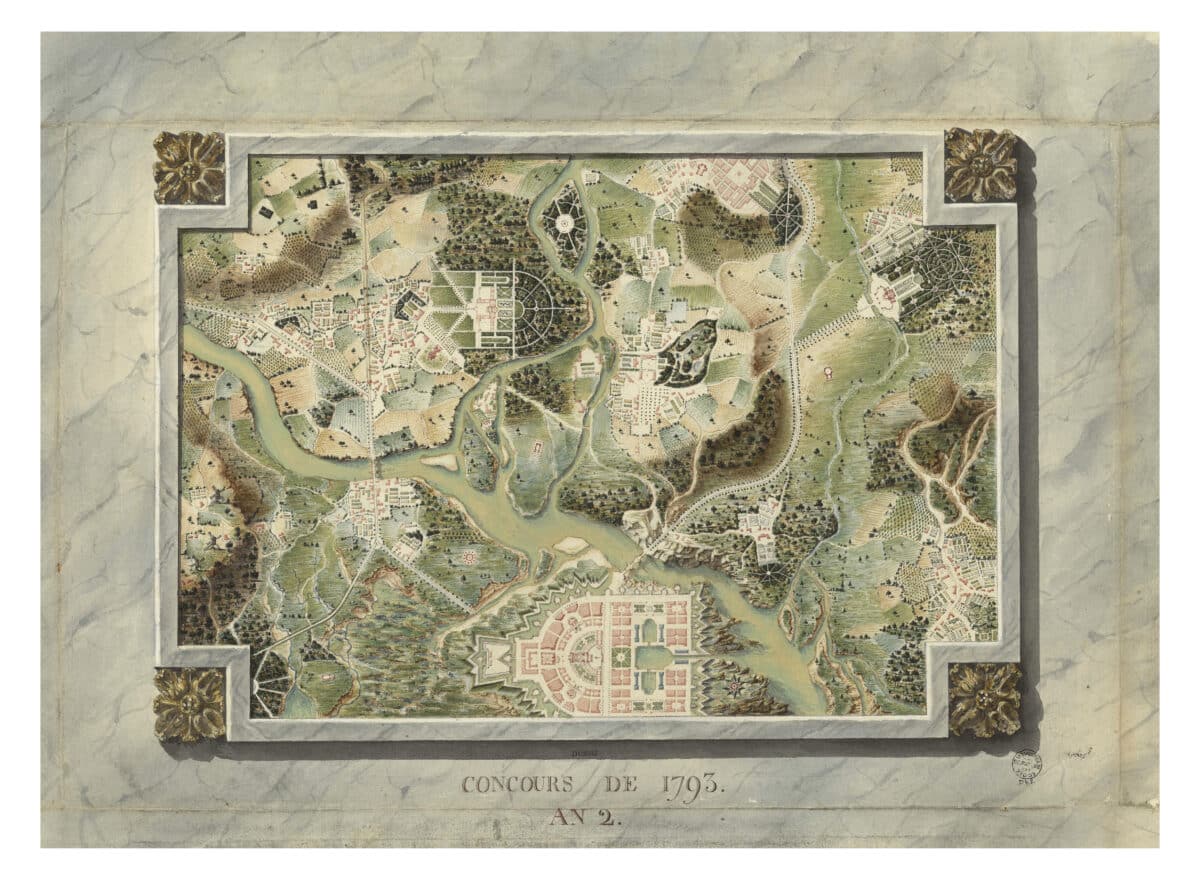

There are four categories of drawing: the map, the ornament, the figure, and the landscape.[1] From 1775 onwards, the construction of the map was tested and further developed. Breaking free from reality, a medium for demonstrations of virtuosity, the map conjured up all kinds of configurations on imaginary territories, anchored in the realm of the plausible, thanks to the layout of roads, rivers, and bridges. With architecture holding a prime place in the curriculum, the engineer was able to master the different facets of representation by copying prints of picturesque landscapes or tracing shaded arrangements, portraits, classically inspired nudes, typography, musical scores, or round sculptural ornaments. This provides an opportunity to combine all these exercises into a single document. In these student works, some of which we are publishing exclusively, the washes are enhanced with ink or red chalk, in keeping with the academic tradition and craftsmanship.

THE EYE AND THE WORD

Often unrolled on a wooden tray, the maps with their unruly corners reveal the subtle play of shadows left by the embossing of typefaces or the metal plate of the prints on the paper after it has passed through the press. Playing cards, business cards, cardboard—the play on words also extends to toponymy: ‘The Nile’ borders the foothills of the imaginary town of Villefort, and the road to Memphis leads to the French gardens of Château de l’Averdine. A contemporary of the new practices of the Ponts, the painter Louis-Léopold Boilly, on show at the Musée Marmottan Monet until 2 March 2025, creates extra-flat trompe-l’oeils. He is the author of a famous table with a built-in ‘pocket’, a synthesis of the studiolo and the veined support for engineers’ documents, where broken glass, coins, and playing cards are displayed.

Louis-Léopold Boilly (1761–1845), Trompe-l’oeil with coins, on the top of a pedestal table, circa 1808-1814, oil on vellum mounted on mahogany, 48 x 60 x 76 cm. © Palais des Beaux-Arts de Lille.

This mix of genres came to an end with the advent of the July Monarchy in 1830. With economic and industrial development prioritising efficiency, a certain split in the practices between architects and engineers began to emerge. Over the past ten years, however, Bernard Vaudeville, president of the Civil Engineering and Construction department at Ponts et Chaussées, has revisited this historical tradition by reintroducing the observational drawing of structures and landscapes into the establishment. This initiative highlights the importance of drawing for the humanistic development of future engineers. And of future architects?

*

Thanks to Guillaume Saquet, Deputy Manager of the ENPC Heritage and Archives Department.

Notes

- Antoine Picon et Yvon Michel, L’ingénieur artiste Dessins anciens de l’Ecole des Ponts et Chaussées (Paris: Presses de l’École Nationale des Ponts et Chaussées, 1989).

Mehdi Zannad is an architect and a lecturer at the Paris-Malaquais School of Architecture. He regularly exhibits his drawings and also works as an illustrator for various architectural firms. His work was incorporated into the FRAC PACA collections in 2016.

– Iris Moon