Just Begin: The Convent Sainte-Marie-de-la-Tourette

– Stan Allen and José Oubrerie

‘The first line on paper,’ Louis Kahn once said, ‘is already a measure of what cannot be expressed fully.’ This captures perfectly the anxiety of beginnings: not what is to be expressed, but everything that will be left out, and an inevitable sense of loss over all the unexplored possibilities. That is why I like to pass on to my students John Cage’s advice: begin anywhere. For Cage, music is a complete universe, and you can enter it at any point and find something to work with. I also like what his friend Morton Feldman said: ‘I have always found it more beneficial to experiment with fountain pens than with musical ideas.’

There is another way to dispel the anxiety of beginnings. Nobody begins from scratch. Every architect, consciously or not, draws on a reservoir of past ideas and forms, and, as a career unfolds, past experience: incomplete projects, intuitions and half-formed thoughts that have been put aside to revisit later. The desire to do something new (and not simply repeat) is one source of the architect’s anxiety. But at the beginning, every architect repeats; more useful and suggestive to me is the idea that a project is never fully contained in its beginning. I’m sceptical of the notion of the ‘pregnant’ moment, the flash of insight that encompasses everything to follow. The first sketch is just that: a beginning, an intuition to be developed, and whatever is drawn there will change and evolve as it is fleshed out. If there is no capacity for change, it’s a flawed beginning. It’s about having confidence in the inner logic of the project, which derives as much from the discipline as from the individual. Just as many writers talk about characters in a novel taking on a life of their own, a good design proposition dictates its own course.

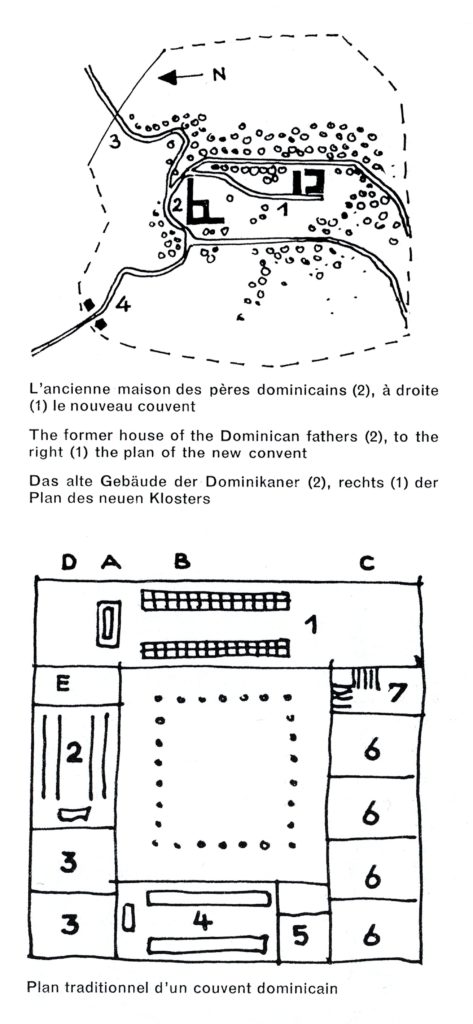

The Convent Sainte-Marie-de-la-Tourette is one of Le Corbusier’s most enigmatic buildings. Radically abstract and sculptural, the building nevertheless honours the layout of the traditional Dominican monastery. Architecture’s elemental capacity to give form to the relationship between individual and collective finds its perfect expression in the monastery programme. La Tourette is a profoundly spiritual building that offers a fully realised vision of a life dedicated to meditation and retreat, punctuated by communal celebration. But it had to start somewhere, and it would be impossible to say that all that abundance was already implicated at its very beginning.

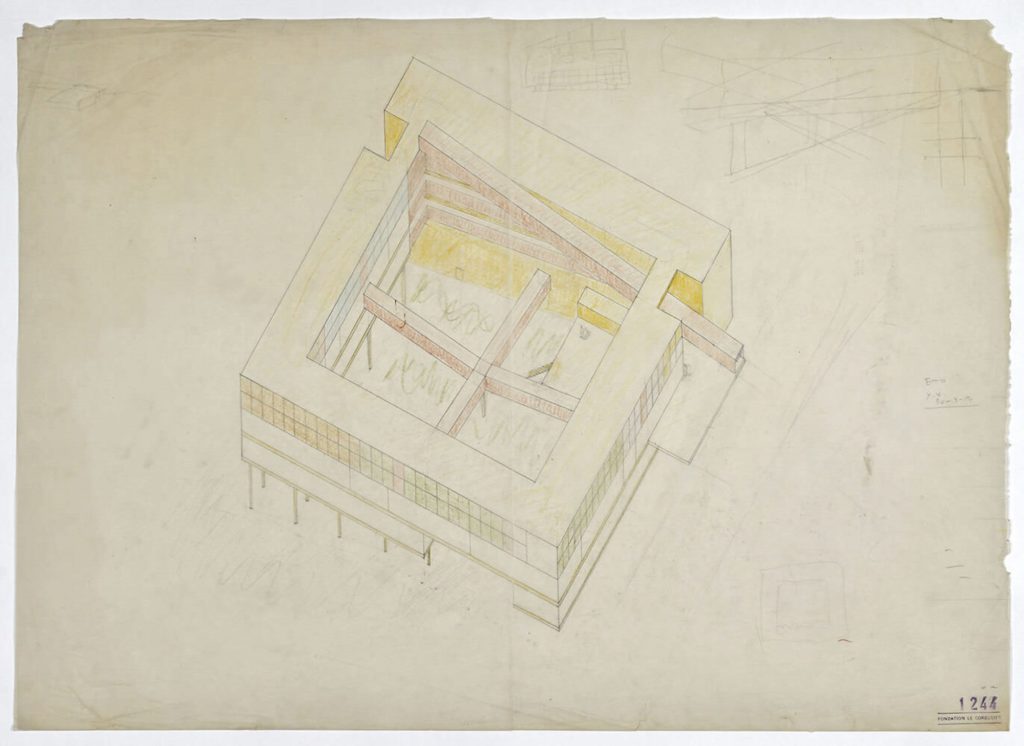

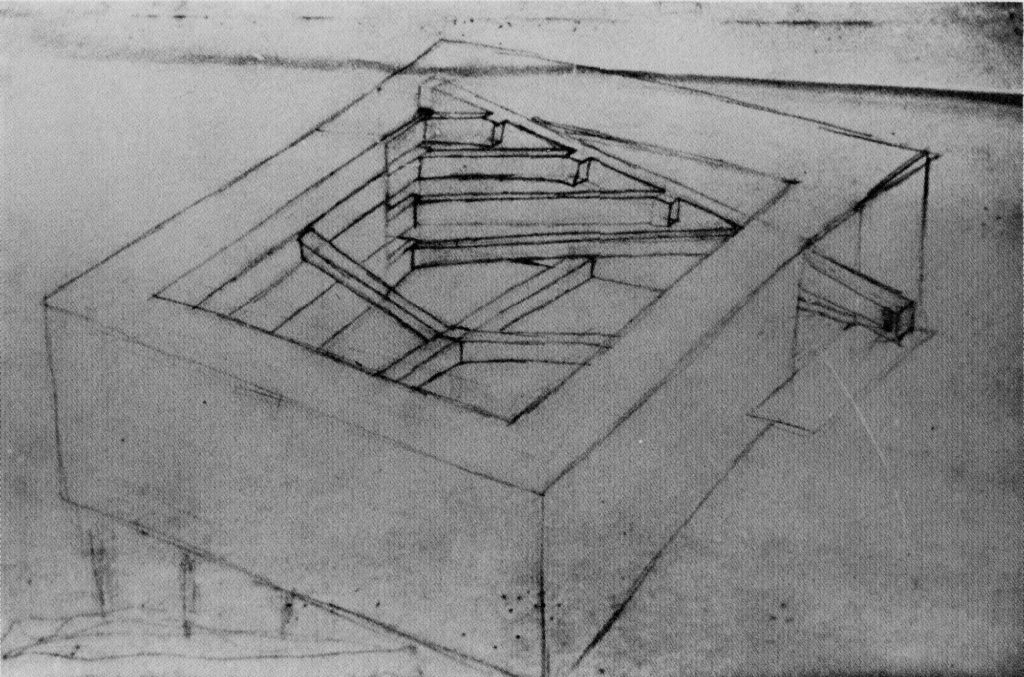

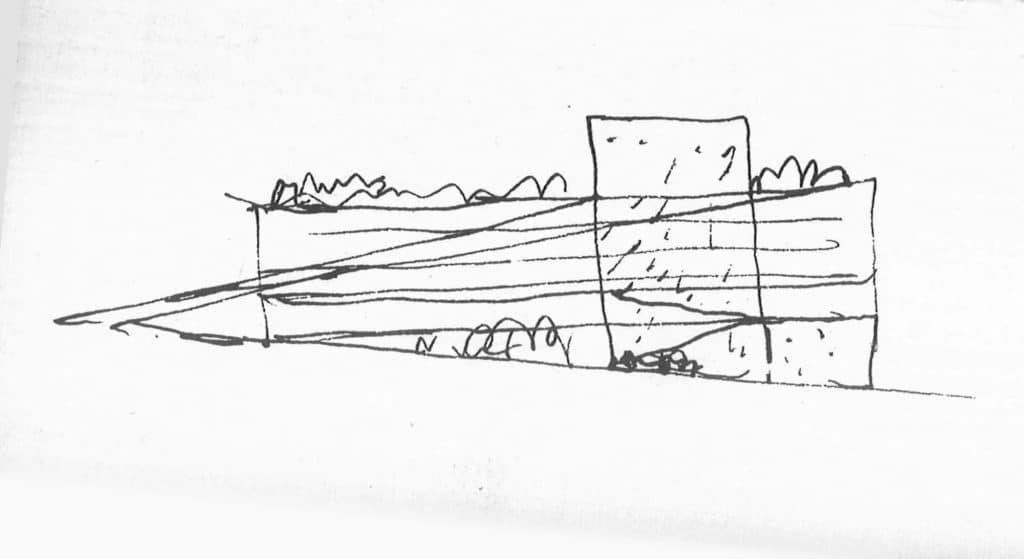

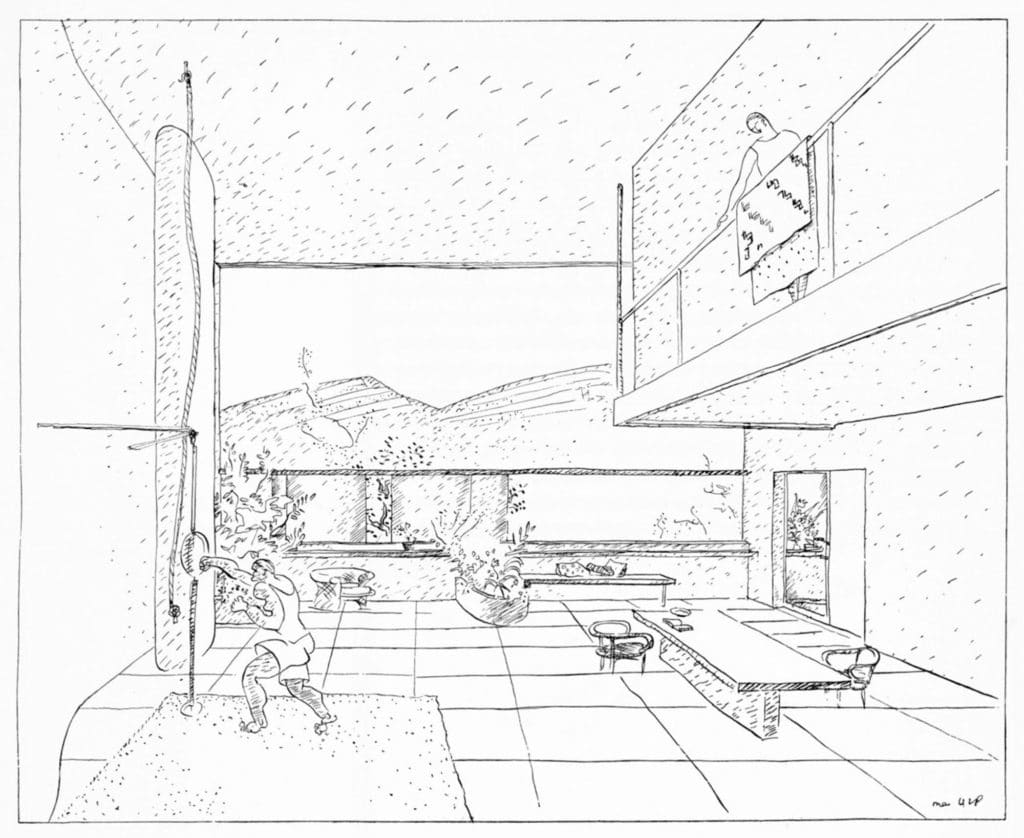

In particular, there is an early drawing of la Tourette that has always fascinated me. It’s an axonometric study, signed Y.X. (Iannis Xenakis), and dated 30/3/1954.[1] All of the basic organisational logic of the monastery as realised is already present in the drawing: a blocky ‘C’ shaped courtyard closed by the blank volume of the church to the north, and entered at the gap between the two. There are lightly drawn pencil notations on the upper right showing what appears to be the volume of the building against the sloping site, and an upside-down elevation – perhaps drawn by Le Corbusier as he stood on the other side of the drawing board? The cross-shaped passageways (the ‘conduits’) that he added to facilitate communication between the wings are present, although in somewhat anemic form. They intersect in the exact centre, and the lateral arms are inclined downwards to meet the passageway to the church. A grid of windows indicates the presence of the individual cells on the upper levels and the collective programs (library, refectory) below. It is a drawing at once economical and concise, yet also highly suggestive. Despite its reductive character, I would hesitate to call it diagrammatic. It is a fully formed architectural proposal, rich with design intention and organisational detail.

And yet… It is also possible to say that this drawing captures nothing of the character of the realised building, and in many respects, suggests the contrary. The forms in the drawing are taut and prismatic; they have little to do with the robust plasticity of the monastery as built. The orange shading on the wall of the church shows that it follows the sloping ground, but the body that wraps the courtyard is lifted up on slender columns that recall the piloti more characteristic of an earlier period of work. In one of his very first sketches, Le Corbusier identifies them as such. But by the 1950s Le Corbusier had long since moved away from the purist forms, lightweight construction and smooth white surfaces of the 1920s which seem to be recalled in this drawing.

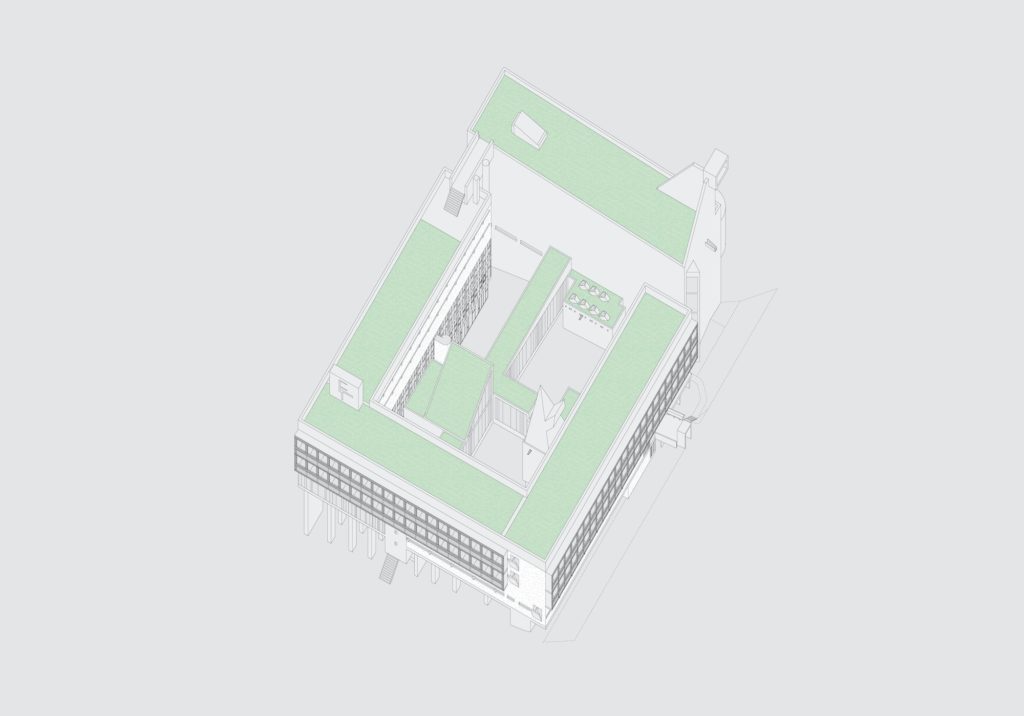

There are a hundred small things that make the building distinct from the drawing, and a handful of larger moves. The arrayed cells for the Dominican brothers clustered at the top of the block are a readymade, borrowed from the recently completed Unité in Marseilles. Their brise soleil balconies extend beyond the face of the building, giving the building a top-heavy feel. The church is more definitively detached from the cloister, and the cross-shaped conduits have been displaced from the center and given a pin-wheel configuration by the addition of the atrium. The lateral wings that enclose the courtyard have been elongated, so that the plan is no longer a square; the courtyard which before was static and empty, is now inhabited: by the diagonal roof of the atrium, the pyramidal form of the Youth Chapel, and by currents of movement that cross and pivot.[2] The matchstick columns have been replaced by robust piers and sculpted supports – the ‘comb’ proposed by Xenakis. As constructed, the block is rendered as weighty and physically present through the plasticity of the form and the texture of the rough concrete. It could be argued that a drawing will never fully capture weight, texture, and materiality, but it can always be notated. Here, the drawing is all about surface and volume while the building is about mass and plastic form.

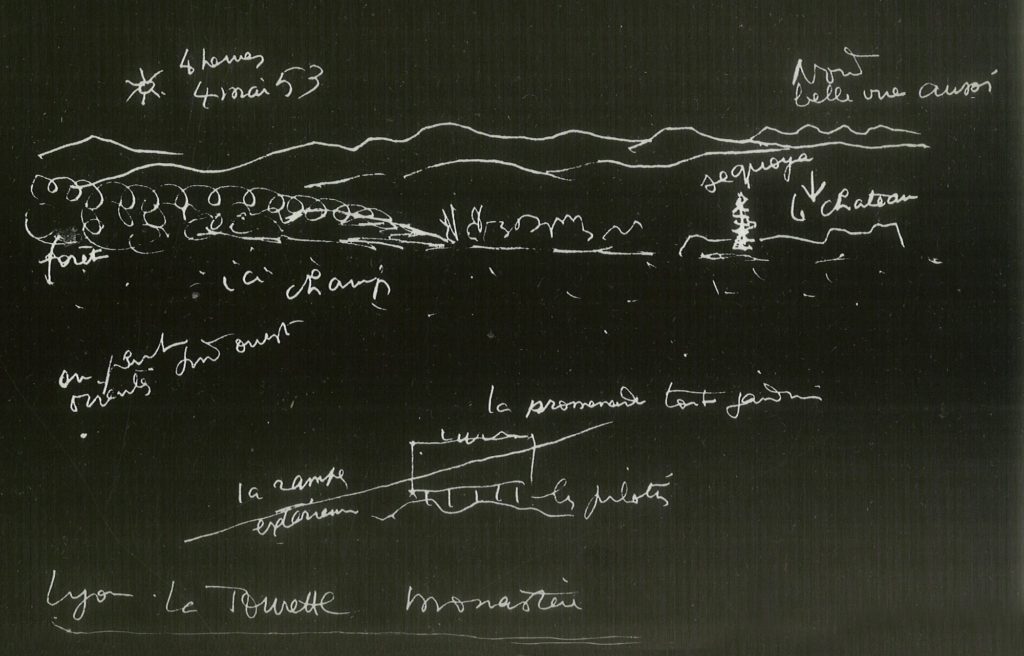

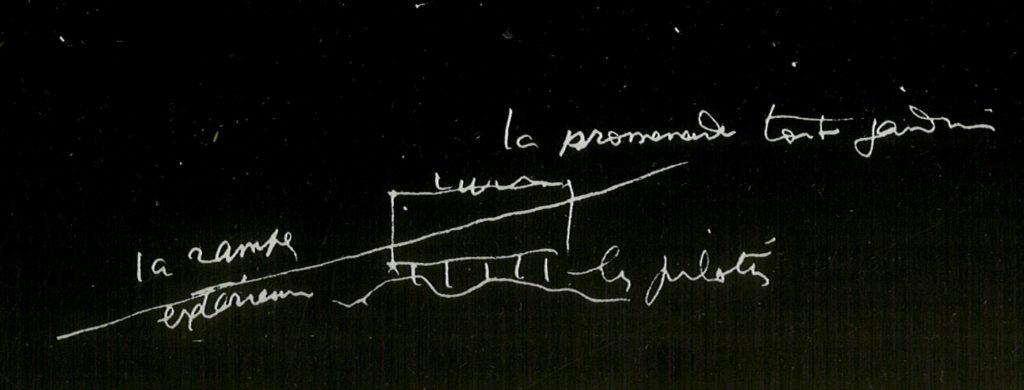

Building and drawing diverge in another important respect. At La Tourette, the relationship to site is everything; it is impossible to understand the building as an autonomous object.[3] Even the enclosed courtyard is activated by framed views of the horizon beyond. But there is no horizon in an axonometric. As a drawing type, axonometric tends to locate the object in an abstract, infinite space. In this case, the slope of the site is lightly sketched in, and inferred by the changing length of the columns, but not delineated as such. The horizontal datum is the roof and not the ground. Le Corbusier wrote that, at the very beginning of the design process, he ‘sniffed out the topography’ and drew the four horizons. His first intuition, evident in a sketch made on site at four o’clock in the afternoon of May 4th 1953, was to elevate the building above the ground, and to displace the conventional cloister and ambulatory to the roof itself, creating an elevated circuit that inverts the conventional relationship to ground. He later explained: ‘Here in this environment which is so mobile, so fluid, so shifting, descending, flowing, I said: I am not going to establish the position from the ground because it flees… We establish the position from the horizontal at the top of the building, so that it will be composed with the horizon.’[4] The building is anchored to the horizon by the double range of gridded cells on the upper levels. Their shadowed balconies render them weighty, and their insistent repetition serves as a foil to the sculptural elaboration of the structure below, which appears to hang, and descend to the sloping ground, more than lifting the building up.

The monastery then, is a kind of machine to make the horizon visible. This explains one of the stranger features of this drawing. The angle of the drawing calls attention to the south wall of the church, and shows the circulation system Xenakis had envisioned to connect the roof to the activities below. A covered ramp ascends from the entry platform to the roof itself, collecting each of the lower-level corridors as it rises. This assertive diagonal (which was already indicated in Le Corbusier’s first sketch on site), is a logical solution to gain access to the roof, and a reliable element in the Corbusian vocabulary: ‘a stair separates, a ramp connects.’ But it also seems to be another gesture toward the fleeting ground, now partially integrated into the monastery itself. None of these variants were realised, although diagonals appear insistently in the final project, from the optical adjustments in the profile of the church noted by Colin Rowe, to the clerestory of the atrium, or the diagonal of the belfry.

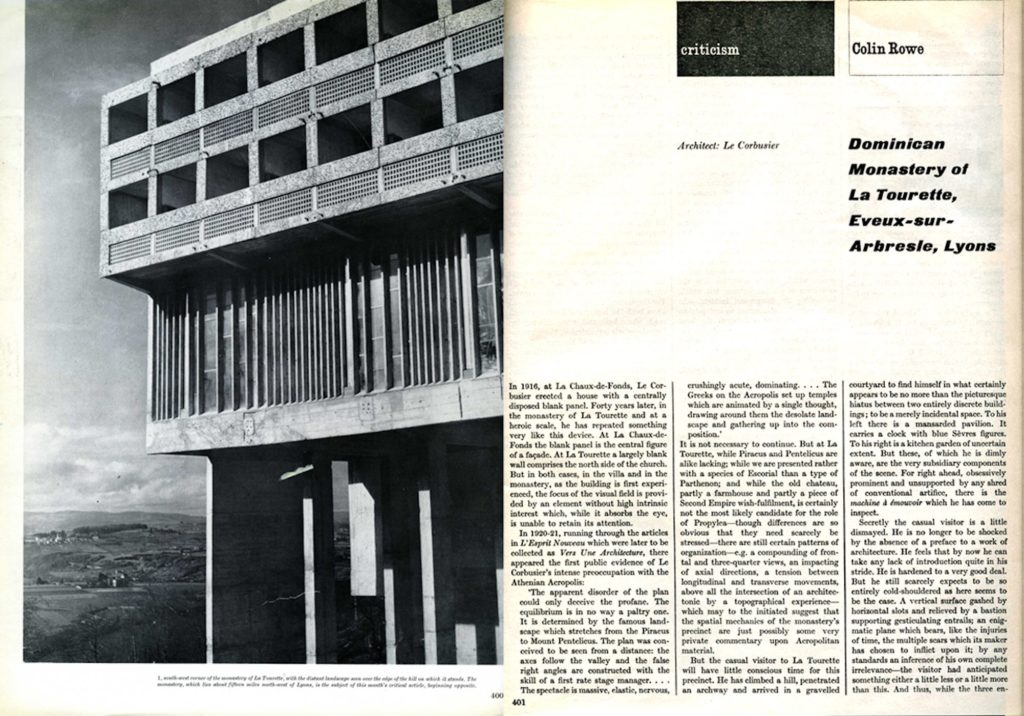

La Tourette is indifferent to the near landscape at the same time as it activates the far landscape. The visitor approaches from the north, the only face of the building to be seen frontally. The blank expanse of the church – punctuated by the light cannons of the chapel below and the sculptural presence of the belfry – creates an anticipatory tension, which is only released as the visitor turns the corner to enter. In a review published shortly after the building was completed, Rowe describes this choreography of building form and distant view in dramatic terms: ‘…as the church is approached, the site which had initially seemed so innocent in its behaviour becomes a space rifted and ploughed up into almost unbridgeable chasms.’[5] The building is geological in its implacable, mineral presence, like a random escarpment or a rock outcropping. Rowe calls attention to the subtle angling of the roof of the church (which counters the slope of the site) and to the dense rhythm of the other three facades, which are always seen obliquely, in dialogue with the distant horizon.

At La Tourette, Rowe writes, ‘Architecture and landscape are lucid and separate experiences, like the rival protagonists of a debate who progressively contradict and clarify each other’s meaning.’ In Rowe’s reading of the building, this dialectical interplay of contradictory terms ripples down, from landscape and site to formal organization (frontality and rotation), to the tension between the rational and the poetic in Le Corbusier’s design ethos, the austerity of material realization against the extravagance of sculptural elaboration, the weighty presence of the brut concrete contrasted to the painterly surfaces, even to the monastic program itself and the dilemma of belief in the mid-twentieth century: ‘There is nothing ingratiating or cheap; and, as a result, the building becomes positive in its negation of compromise. It is not so much a church with living quarters attached, as it is a domestic theatre for virtuosi of scepticism, with, adjoining it, a gymnasium for the exercise of spiritual athletes.’ For Rowe, Le Corbusier’s secret avatar – the boxer stripped for combat – has been transmuted into Jacob wrestling with the angel.

What I hope I have shown is that while this early drawing gestures toward all that rich, expansive capacity in the realised building, it by no means contains it. And yet without this simple beginning such a complex synthesis could never have been achieved. This is the paradox – and the anxiety – of beginnings. The drawing tells us little about the building as a fact in the world. Architecture stands on its own and does not need to be propped up with a narrative of process. But the drawing also tells us everything about the long and difficult process of making a building as compelling and enigmatic as La Tourette, and the need to begin, just begin, somewhere.

Postscript

As I started writing this short article, I contacted José Oubrerie, who worked in the atelier at 35 Rue de Sèvres from 1957 to 1965. The following are extracts from his email responses to my questions, received when I was close to finishing my text. It seemed more interesting to preserve his language (and sense of humour) rather than incorporate them into the text. I want to thank José for his readiness to respond, and for calling my attention to the early sketches which are published here.

Mon 13/7/2020 11:26 AM

For the drawing I think that it is easy to answer you … At this time, just the 5–6 years before us you had in the Atelier rue de Sevres 3 people left; Tobito, Maisonnier and Xenakis and each one was more or less at the same time in charge of one project alone (and collaborated for bigger ones as we did too). Tobito working on the Governor’s Palace in Chandigarh, Maisonnier more concerned with the studies of Ronchamp and Xenakis with La Tourette: this drawing (and others) was (were) done by Xenakis, it was his proposals for the conduits inside the courtyard and ramp going to the roof-terrace as always emphasized by L-C and Xenakis was even reinforcing this specific quality of discovering on the terrace the horizon, the sky not primarily the view…you should realise that we were working in the constant solicitations of L-C towards us to bring ideas, any contributions we deemed important etc… We were working like in a studio at school but L-C was making the decision of what was ‘convenient’ for his view of the project and we were both himself and us in charge of making discoveries inside the problematic of the project…he could tell you in the morning, discovering what you were proposing, he could tell you something like: ‘this is very good but does not fit in my vision, keep it for yourself…’ He always enjoyed to see that you were reacting and inserted yourself in the project.

You surely have seen some other proposals of Xenakis for the bell-tower etc… Amusing story: in the spiral stair Xenakis made the steps very high and uncomfortable to bother the monks as he did them very small toilets etc…let me know if you have other questions about drawings etc…there are others like that I think with this proposal of the ramps by Xenakis. Some of his proposals remain, like the ondulatory on the facades or the ‘comb’ the concrete arched support of one conduit if I remember well…

Mon 13/7/2020 1:39 PM

I suppose Stan that you have an edition in French or in English of the book about La Tourette des editions Forces Vives de Jean Petit […]

This book, if you look at its very details, is a story post-realization. Xenakis’ hand appears in many pages, and you can see the problem of your drawing indicated by L-C pages 112/113 (French edition) called ‘Les Croquis’ dated 19 Sept year not indicated, probably when he went to the site for the first time […]

Corbusier would always start a project in going to the site to see what it would give to him, this is dated May 53, what I call his ‘Inspector Maigret’ technique to go to the site, the place of the crime, and ‘sniffle’ (renifler?) with his nose what it suggested to him… here evidently it was the slope of the ground and the landscape…the bottom sketch, page 112, indicates a system of ramps similar to Xenakis’ drawing, is it coming from the page of May where you see a building crossed by a diagonal line…? Probably it is how this idea initiated but the sketch page 112 is closer to how Xenakis developed it…and you know, L-C would very often, when we had made a step that he accepted on a project, sketch it in his sketch book…it is why for me the ‘historians’ make many mistakes of interpretation… attached drawings white on black background of May 4th 1953, 4 o’clock in the afternoon.

Mon 13/7/2020 4:34 PM

The axonometric was not so much in use at our time and before because the practice of models was our 3D way to figure out the space or the light etc…it was more and more practiced by us and existed also at Xenakis time. He himself was making models for different purposes like studying the light in La Tourette church, looking inside it by a hole and so on…it is curious if you remember the admiration of Corbusier for Choisy which inspired later his axonometric drawings in color for, I think, the Cahiers d’Art. […] We were using a lot the color coding for drawings, line drawings by hand or models, I remember the tons of models […]

Don’t hesitate if you need other things if I can respond I will…

But we have from working in the studio a different view of Corbusier…

Notes

- There is a detailed account of the design process in Iannis Xenakis, ‘The Monastery of La Tourette,’ in H. Allen Brooks, ed., Le Corbusier (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1987), 143–162. For obvious reasons Xenakis spends quite a bit of time discussing the ‘pans de verre ondulatoires’ which he worked out borrowing techniques of musical notation and employing his considerable mathematical abilities. A more historical account can be found in Sergio Ferro et al, Le Couvent de la Tourette: Le Corbusier, (Parenthèses, 1988).

- Although this elongation is clearly visible in the plans, it only became obvious to me when we placed our axonometric reconstruction (made for this article), next to the original. Perhaps it was a functional adjustment necessary to gain more space; but that could have been accomplished in many ways. It is no accident that the body of the monastery has been elongated parallel to the slope of the site, which makes it less of an object and more like a geological feature. It is also completely consistent with Colin Rowe’s observation that these elevations are always seen obliquely, which tends to compress their length – a form of optical adjustment occurs in which the perception of the block from the exterior is returned to its original compact form, while the interior is more directional.

- See Damisch, Hubert, trans. Julie Rose, ‘Against the Slope,’ Log, no. 4 (2005): 29-48. Damisch argues against the idea that the form of the building is dictated by the site, proposing La Tourette instead as a ‘theoretical object,’ that is to say, a generalizable exemplar of its type. I don’t disagree with this reading, and have written elsewhere that, in general, the architect does not so much fit the building to the land as fit the land to the building. But it does not negate the idea that site and building are inseparable in both experience and in the process of design and construction.

- From a 1960 interview with the Dominican community; cited in: Jean Louis Cohen, Le Corbusier: An Atlas of Modern Landscapes (New York: Museum of Modern Art, 2013), 218. An alternative translation appears in Damisch, 39: ‘Here, in this terrain that was so mobile, so receding, descending, flowing away, I said: I’m not going to make the base on the ground since the ground gives way or else it will cost as much as a Roman or Assyrian fortress. We don’t have the money and this is not the time. Let’s make the base high up, at the horizontal of the building at the top, which will then square with the horizon. And we’ll measure everything else from this horizontal at the top and we’ll get to the ground when we touch it.’

- Colin Rowe, ‘Dominican Monastery of La Tourette by Le Corbusier (Eveux-Sur-Arbresle, France)’ in Architectural Review, 6 June, 1961; reprinted in The Mathematics of the Ideal Villa and Other Essays (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1976), 185–204

– Ptolemy Dean