Lauretta Vinciarelli’s West Texas Types

Lauretta Vinciarelli was born in 1943 in Arbe, Italy and raised in Rome. In the mid-1960s she attended graduate school at the La Sapienza University in Rome, earning her doctorate in architecture and urban planning in 1971. As a student she encountered the typological and vernacular approaches to housing and urban design of Ludovico Quaroni and Mario Ridolfi, which provided a foundation for some of the critiques of market capitalism and materialism that permeated Italian architectural discourse in the late 1960s and 1970s, as well as a way of working throughout her career as an architect.

In 1969, Vinciarelli moved to New York City, becoming involved in the activities of the Institute of Architecture and Urban Studies (IAUS) in 1975 and continuing until its closure in 1984. She was the first and, ultimately, the only woman to be given a solo show by the IAUS, in 1978. With her IAUS colleagues Bernard Tschumi, Joan Ockman and Mary McLeod among others, Vinciarelli was a vital member of the ReVisions study group, formed in 1981, and which hosted public events that explored the relationship of art, architecture and ideology, and organised reading groups that focused on texts by prominent Italian architects and thinkers, such as Manfredo Tafuri, Galvano Della Volpe and Antonio Gramsci. Vinciarelli taught at various architecture schools throughout her career – starting at the Pratt Institute in 1975, and later City College New York (1985–1992), before joining the University of Illinois at Chicago (1981) and Rice University (1982) as a visiting professor. Significantly, in 1978 Vinciarelli was hired by James Stewart Polshek, Dean of the Architecture School at Columbia University, making her one of the first women to teach studio courses, along with her colleagues Ada Karmi and Mary McLeod.

Vinciarelli’s pedagogical practice had developed in an atmosphere of Italian political protests beginning in the early 1960s and was fomented by the impact of the worldwide protests of 1968. While at La Sapienza, she also encountered and participated in the violent unrest of the 1968 Italian Sessantotto, or student protests. The Battle of Valle Giulia, one of the most violent clashes between students and police, took place on the La Sapienza campus. Her work and teaching questioned the entrenched principles of modern architecture. She sought to rethink these values through the study of building typologies and their relationships to specific social and physical contexts. While at Columbia, Vinciarelli introduced ‘the type’ and led courses on carpet housing, one of the four primary housing typologies taught there. Similar to the layout of ancient Mediterranean villages, which balanced individual and community spaces, carpet housing deploys private and shared courtyards in low-rise, high-density apartment designs that resemble a textile or carpet when viewed from above.

In addition to her teaching legacy, Vinciarelli’s contributions to the field of architecture include her visionary drawings, which were produced during a period of increased interest in paper architecture and the presentation of architectural drawings in an art context. She used a typological approach to drawing, which centred on common physical characteristics shared by buildings identified with a particular place, such as the hangar and courtyard study, highlighted here. Vinciarelli developed a method of ‘drawing as research’, which is vividly demonstrated in coloured pencil and watercolour in her architectural proposals and drawings from the 1970s and 80s. As architect and scholar George Ranalli wrote of Vinciarelli’s work, ‘Her drawings place her in a lineage of architectural thinkers that includes Boullée, Labrouste, Ledoux, and Piranesi…Lauretta Vinciarelli was aware that great architecture mediates the relationship between the singular experiences of the individual and the collective experiences of society.’ Additionally, as Vinciarelli scholar Rebecca Siefert has noted, the work of architects such as Aldo Rossi and Massimo Scolari, demonstrate that ‘bringing time-tested types into the new era was vital for Italian architects in the postwar rebuilding era’. Indeed, Vinciarelli’s drawings for hangars in Marfa, Teas, formerly used by the American military, articulate how these structures, common to the small-town military installation, could be reimagined while maintaining their inherent physical characteristics.

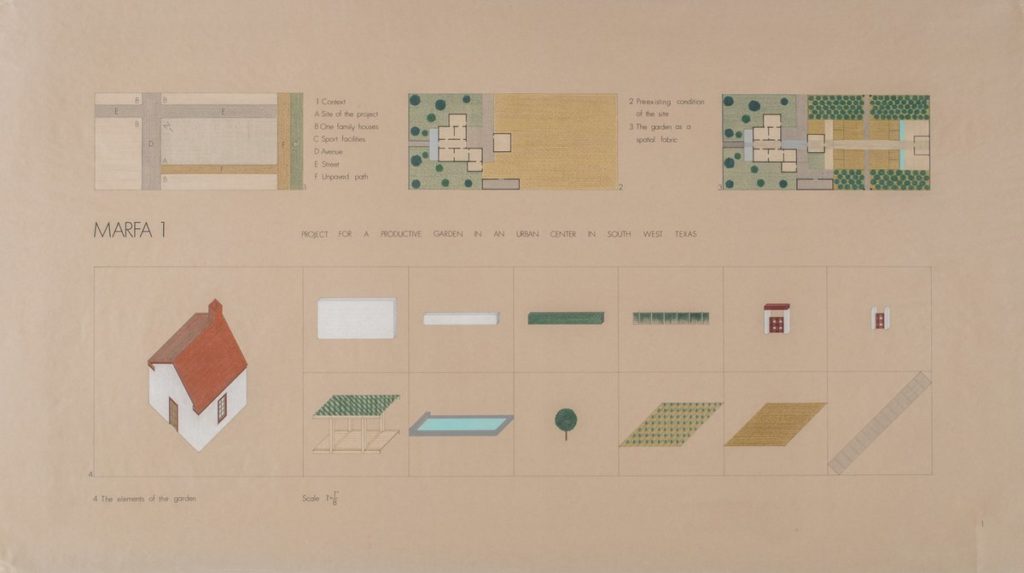

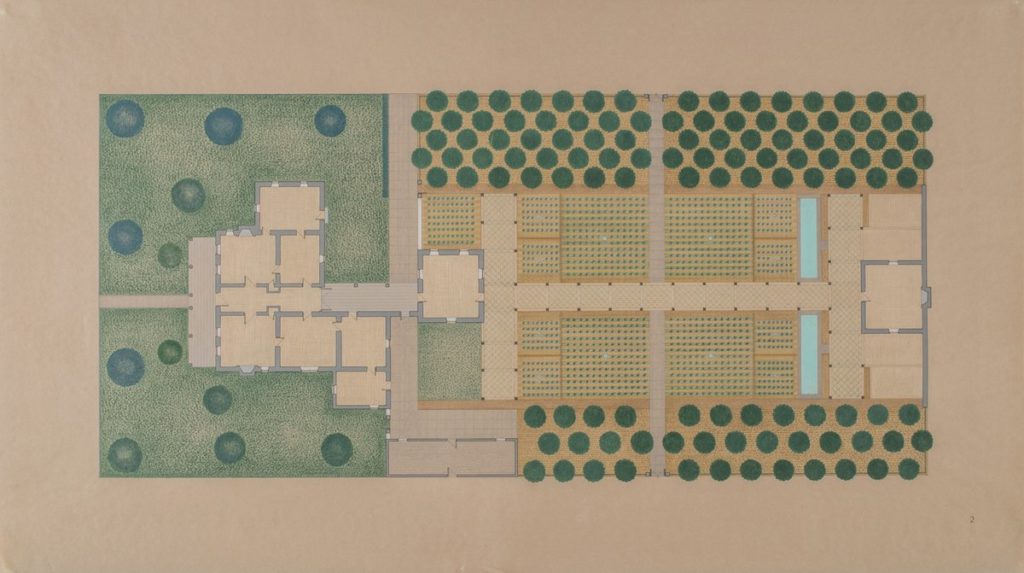

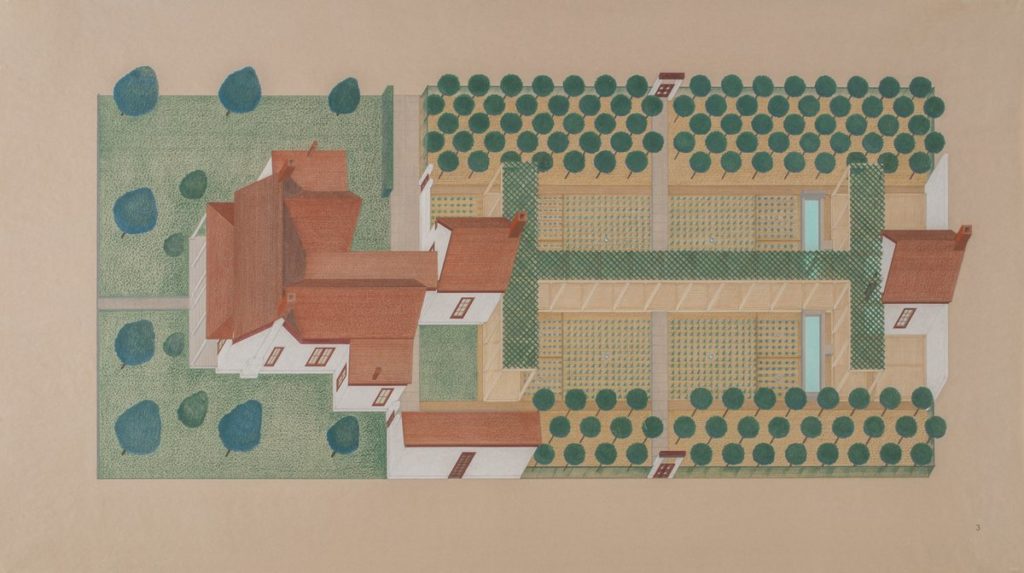

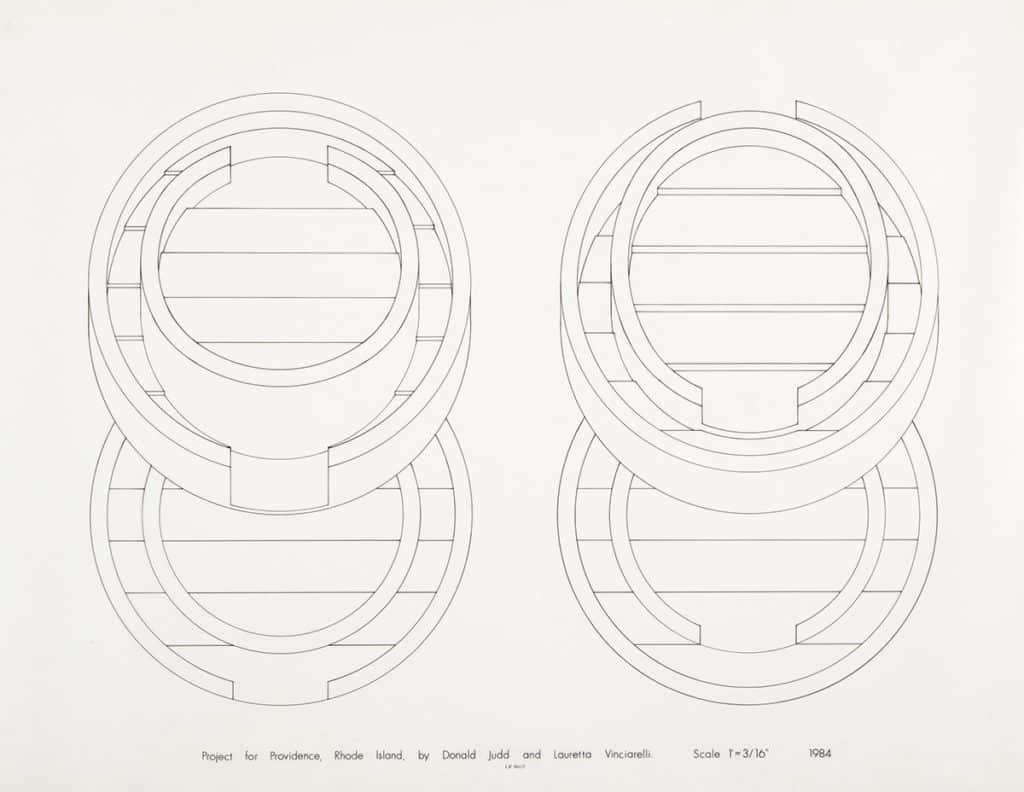

In 1976, Vinciarelli began a ten-year working and romantic partnership with Donald Judd. Their collaboration can be seen in numerous realised and unrealised projects for Marfa and West Texas, such as a set of drawings commissioned in 1979 by Judd for the garden of the Walker House. She introduced a number of elements, from pergolas to water features, which were repeated to create the ‘garden as a spatial fabric’. Though the project was never realised, Vinciarelli’s influence can be seen in the structural elements that Judd incorporated at other sites. For example, the pool for the Walker House closely resembles the pool Judd later realised in concrete at La Mansana de Chinati/The Block; the doors on the north and south side of the property resemble the doors on the north and south side of the Arena at the Chinati Foundation/La Fundación Chinati, the public art foundation that Judd established in Marfa in the mid-1980s. In addition to ongoing projects in Texas, the two also worked on a commission for a monumental sculpture to be installed in front of Providence City Hall (1984) and the design of a large complex for the Progressive Insurance Company in Cleveland (1986).

For the Providence City Hall, Judd proposed a project that would be, in his words, ‘built in place, particular to the site, the whole complex, and with some purpose’, noting that, ‘Since the project was close to being architecture, I asked a friend, Lauretta Vinciarelli, an architect, to be partners.’

Their proposed project was for a series of concentric circles made of granite sand and gravel from a quarry nearby Providence. Each circle would serve a different function, with the main circle allowing for public dialogue by providing a physical platform for public discussion in proximity to the Providence City Hall. As a result of bureaucratic disagreement, the series of circles was decreased to one main circle, and even that, in the end, was called off. As Judd wrote of the situation, ‘Respect for knowledge, even information, can’t exist in such a situation. Cause and result of this is the increasing subdivision of planning, architecture, the design of utensils and furniture, everything, even art is imminent; design becomes Design, a category; everything is in a category.’

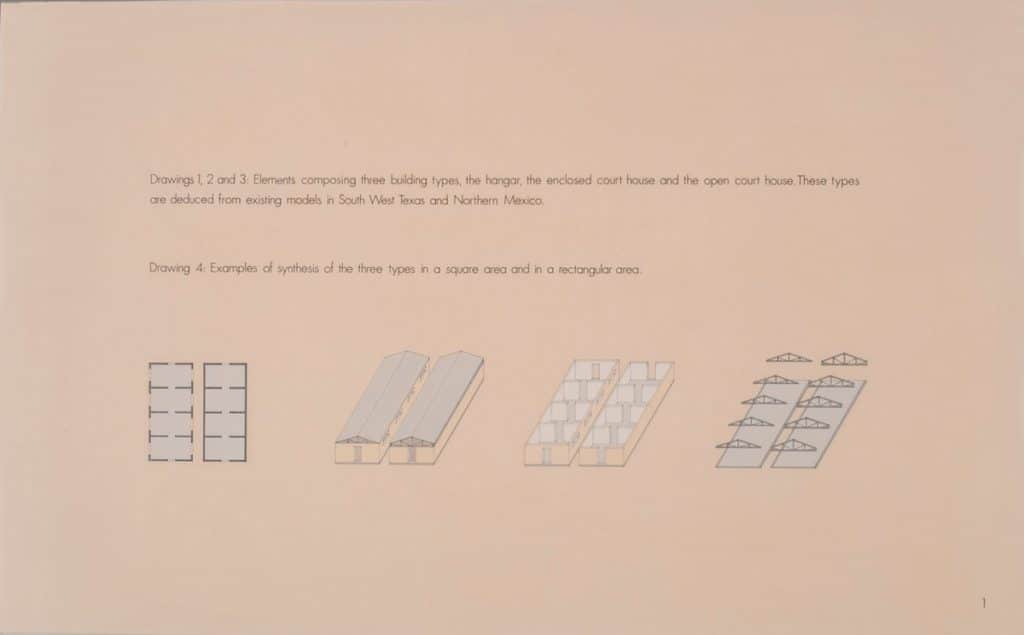

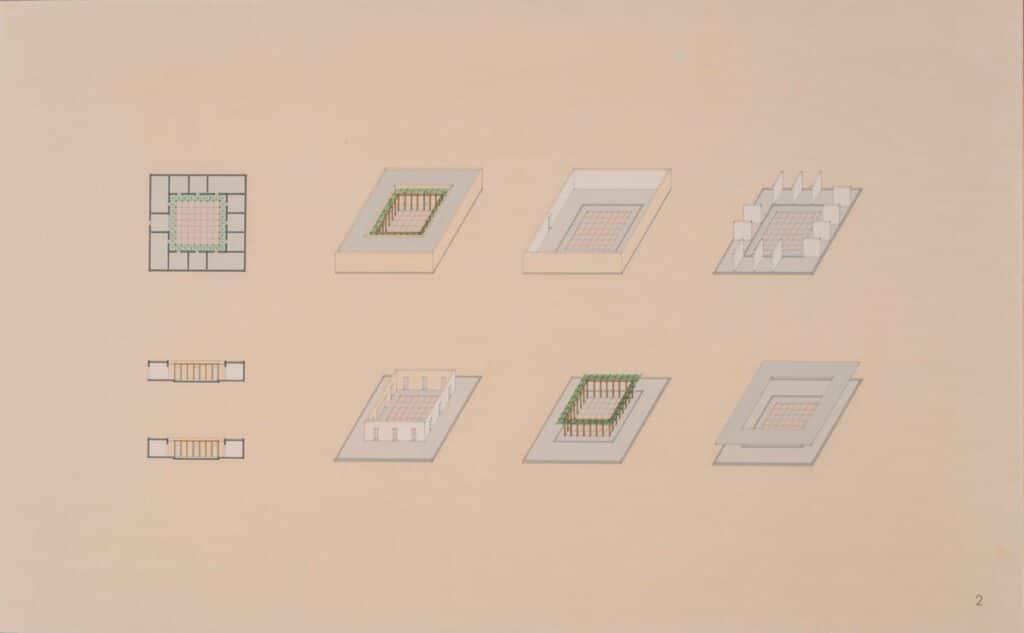

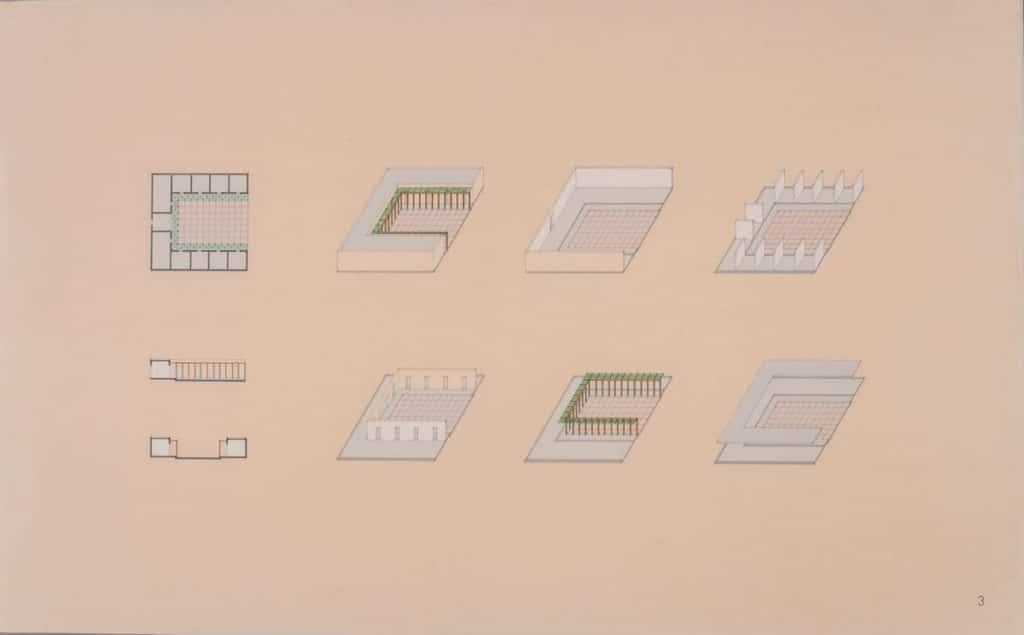

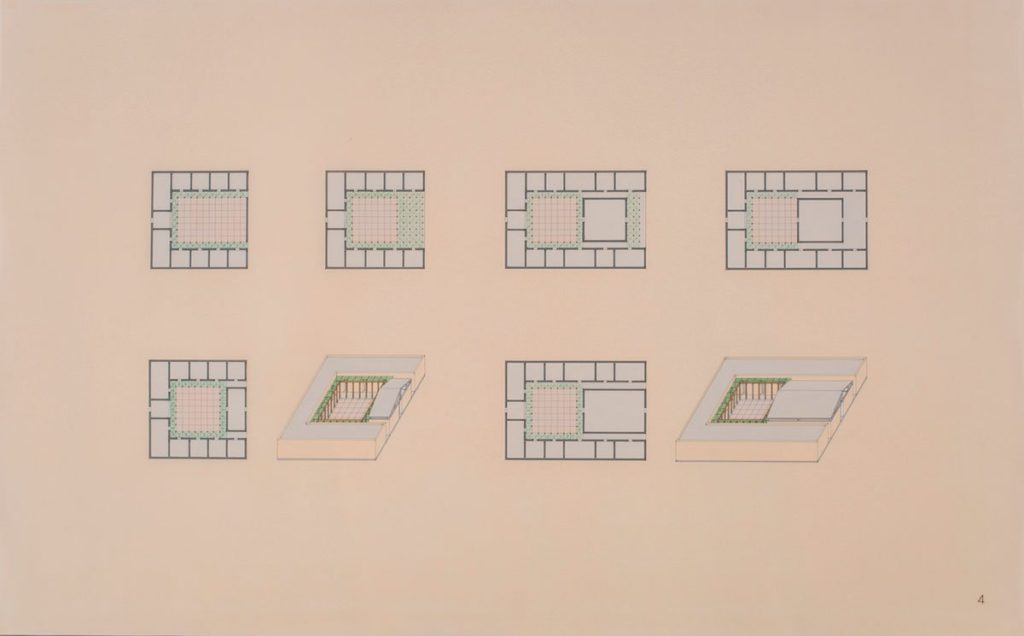

This series (top of page, above and below), of Prismacolor drawings of hangars and open and enclosed court houses from 1980, explores typologies suited to the existing climate, buildings and materials of southwest Texas and northern Mexico. Over four pages, Vinciarelli reveals each type and then combines them to create a spatial fabric, not unlike the carpet housing type she was then teaching in her studio at Columbia. As she stated in a 1978 lecture, ‘architects are asking the question: how can we do architecture that people can understand?… And I intend this question: in which way can we do an architecture which is recognisable? And it is my opinion that the adherence to the historical types can help.’ For Vinciarelli, the typological approach was intertwined with a respect for the specificity of place, using the already recognisable qualities of vernacular styles and adjusting them to meet contemporary social needs. As she wrote in Arts + Architecture in 1981, ‘I do not believe in the validity of a universal building type; in fact the pitched-roof North American house looks defensive and sentimental in Southwest Texas. Its own meaning is debased in its thoughtless repetition by a consumer society that has lost its sense of the specificity of place.’

On the first sheet, Vinciarelli articulates the contents of each of the four pages of drawings to follow. A text description introduces her choice of site, as well as her method of deconstructing types and then reconstructing them into new objects or buildings. Below the text are the first four drawings, which show the elements of the hangar – the floor plan, roof, walls and tresses.

By 1974, Judd had purchased two former airplane hangars in Marfa that had been used as storage for the Quartermaster during the Second World War. Judd renovated these hangars, while maintaining the integrity of their original form, to suit his living and working needs. Using the floor plan provided by the original interior walls, he transformed the discrete spaces of the two hangars into three large rooms that he installed with his work from the 1960s and 1970s, a library, a studio, a bedroom and a kitchen. Judd referred to this complex of existing military buildings and new structures, which he designed for the property, as La Mansana de Chinati or The Block (since it encompasses a full city block). This series of Prismacolour drawings was produced six years after Judd acquired the property that would become his house and studio in Marfa. Although Vinciarelli would have seen these hangars during her first trip to Marfa and may have had them in mind, her floor plan and axonometric drawings of hangars are abstractions of a type, not depictions of specific structures.

The second and third pages each contain eight views of an enclosed and open courtyard. For both, Vinciarelli took a uniform approach, including a floor plan, a front and interior courtyard elevation, as well as axonometric views of the project showing the perimeter, interior and courtyard walls, the pergola as an isolated element, and the floor and roof structures.

The final page combines the previous types, integrating the hangar and courtyard (open and enclosed) over a square and rectangular site. For Vinciarelli, this series of drawings, served as a framework – a way to explore existing typologies to generate architectural possibility. ‘For Vinciarelli – deeply immersed in architectural and cultural history – the idea of type took her in several important directions,’ wrote architect Michael Sorkin, ‘First, to the idea of architecture’s elements, the raw tectonics of anti-gravity, the traditionalised reduction of form, and the creative play of light and space. This investigation quickly converged with parallel investigations in the art world of more purely figural forms of minimalism…In all of her work, she never lost sight of manifold obligations of the architect, to shelter, to illuminate, to organise lines of sight, to act in compact with place, and offer all of this with complete generosity.’ [1]

Notes

- The hangar and courtyard drawings are a chronological midway point in the Lauretta Vinciarelli exhibition, which includes works from the collection of Judd Foundation from 1975 to 1986. Judd purchased a number of Vinciarelli’s drawings included in this exhibition shortly after their realisation. The remainder of the installed drawings and watercolours were gifted by Vinciarelli’s husband, Peter Rowe to Judd Foundation in 2012.

– Helen Thomas