MJ Long’s Doll House

In 2018, I met the architect MJ Long at her home. Located in a building designed and constructed in the 1930s by Thomas Tait, it doubled as Long’s studio. It was formerly the home and studio of the sculptor Sir William Dick Reid; MJ Long and her husband Sandy (Colin St John Wilson) had renovated it in 1974 to make space for their family home and shared practice. The setting could not have been more fitting, given that I was meeting with Long when writing a PhD at the Architectural Association about artists’ studios, and the ways in which our domestic environments have begun to take on the characteristics of the studio, something I have called the studiofication of the home.

In Long’s own practice, she had developed wide experience in the design of studios and homes for artists, and we discussed the question of living/workspaces. I was fascinated by the simplicity of how she thought and spoke about this, often relating the design of studios as a response to temperature. Living and working in the same space, or within close proximity, has in recent years often been misrepresented as a condition of using the dining table to work on a laptop, but Long was interested in challenging the idea that a space for work must have the same environmental condition. She talked about allowing for more corporeal activities, how some workspaces might necessitate ‘a slightly cold environment for working’. In other words, rather than let the building standards of a domestic real estate market dictate the design of living/workspace, perhaps there might be other, looser ways to think about comfort and the arrangement of domestic spaces for working. We talked about this, among other things, through the lens of the ongoing restoration work her practice was carrying on in St Ives, at Porthmeor Studios. I had been conducting research and interviews with the studio inhabitants at the same time, and Long’s deep knowledge of—and care with—the way the renovation works developed in delicate tension with the lives of the artists, the heritage of the buildings, and the contemporary needs of the organisation and wider community were endlessly fascinating to me.

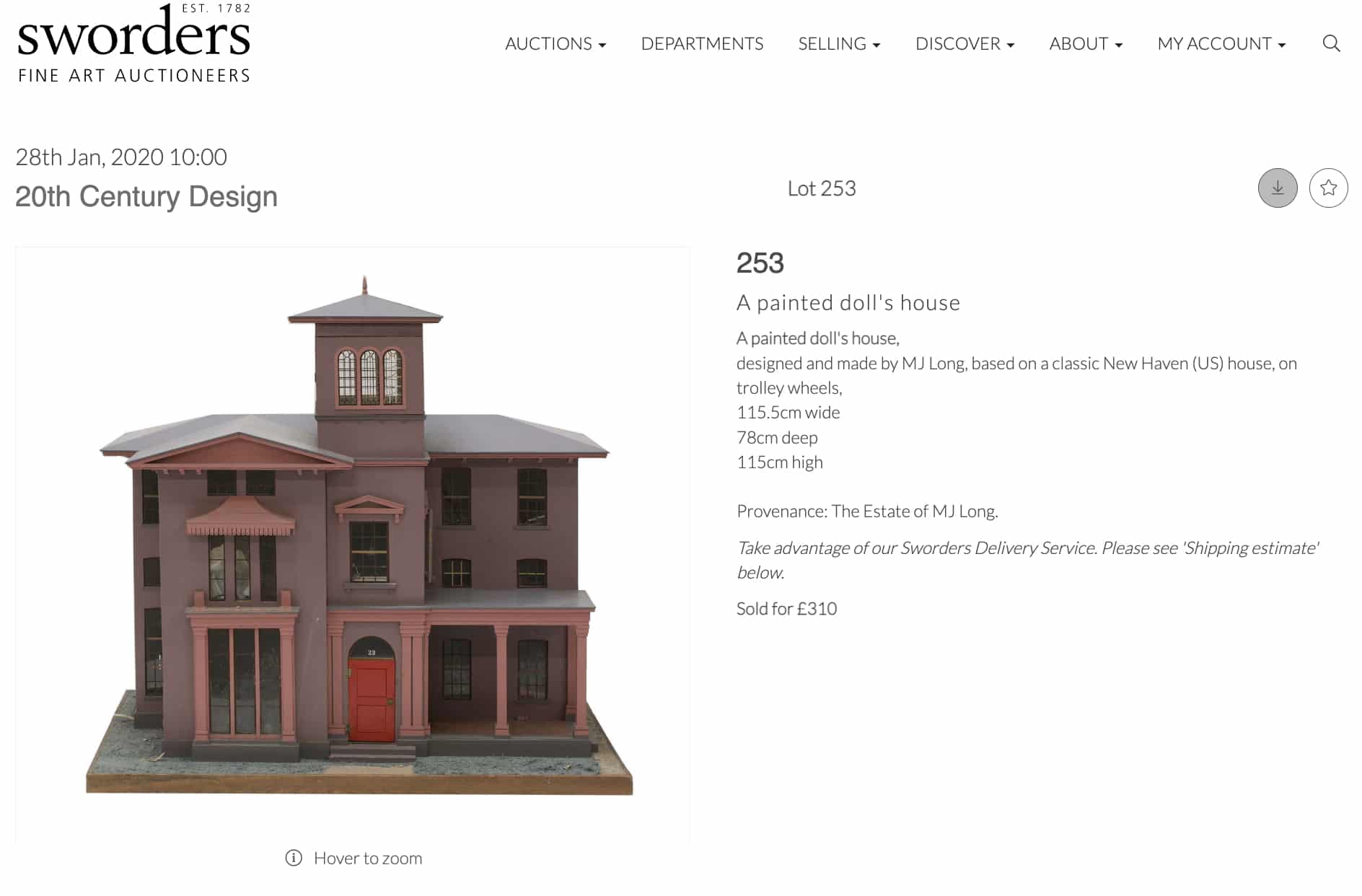

In January 2020, soon after MJ Long passed away, Sworders Fine Art Auctioneers advertised the sale of selected objects from her estate. For an architect who had spent much of her personal and professional life intertwined with some of the most important artists in mid-to late-twentieth-century Britain, the collection was composed as one might expect. A series of plaster pieces and artworks of various kinds made by her close friend Eduardo Paolozzi were among the items on sale. Studies of various sizes for his large sculpture outside the British Library, ‘Newton after Blake’, were included, as were an assortment of maquettes and steel sculptures. Other items from the home she shared with Sandy Wilson were put up for sale: a Blüthner ebonised grand piano, six opaline glass goblets, an American flag, a painted pipe, a Victorian metamorphic child’s high-chair, lamps, carpets, chairs, and many books. But among this general miscellany, there was one item that stood out. Lot 253 was a painted doll’s house. It was quaint-looking, at odds with the rest of the collection. On further reading, I saw that Sworders credited the object to MJ Long, and that it was based on a ‘classic New Haven house’. The online description showed only one photograph, that of the doll’s house’s exterior facade. It looked hand-painted, in tones of burnt coal and mauve. The front door was lobster red, with the number 23 written in white, indicating that, perhaps, the house may indeed have had a real address somewhere in New Haven, Conn. Notwithstanding my own fascination with miniatures, the doll’s house appeared unique to me, and to some extent the most personal, because not only was it made by MJ Long herself, it also seemed distinct from anything she may have made for her practice.

I’m certain there were other lots that would have proved more useful, but this doll’s house held greater allure. MJ Long had died when I was just getting to know her and her work, and this object reflected not only the architect, but also the person that I had first met that day in her house/studio; a mother, an immigrant, and a teacher with whom I shared similar questions and concerns. By some twist of fate, the highest amount I could offer was the starting bid, and my own bid, left unchallenged, ended up winning the auction two days later. Sworders notified me that the doll’s house was mine, but that I would have to either arrange delivery from their storage facility in Essex to London (which would have cost more than what I paid for the house itself) or pick it up myself. My Mexican driving licence and lack of car were the first stumbling blocks in this regard, but my friend Lola offered to drive me the following weekend. Problem solved, I thought. We were received at the warehouse with puzzled, concerned looks on the faces of the warehouse staff. ‘Do you think it’s going to fit in the boot of the car?’ one asked. ‘You should have brought a van,’ another remarked. Moreover, I was surprised to see that Lot 253 was not just a doll’s house, but a litany of miniature furniture, furnishings and objects, none of which had been contained in the original listing. Pressed for time, and alert to the issues of squeezing the house into the car, I swept the objects up into bags for later inspection. With some manoeuvring, the house eventually went into the boot, but upon arrival at my flat in north-east London, the problems really began. My flat was on a relatively busy road, with no real space for parking and loading away from the regular traffic and well-used bus routes. Coupled with the precarious nature of its unloading from the small car, the doll’s house tipped to and fro, emptying some of its precious cargo on to the street. I was heartbroken to see a small porcelain bathtub break in two.

Tiny plates and forks also fell victim to the asphalt. By the time we got to the front door, it was clear the doll’s house would not fit through the door frame in one piece. The security bars across the windows of the flat made removing a sash to gain access a pretty useless endeavour, even if I could have convinced the landlord that taking the windows out was within the terms of our tenancy agreement. Carefully breaking the doll’s house into pieces was mooted, but swiftly rejected. I had started to wonder whether this had all been worth it. In the months following, the artefact found temporary accommodation at a friend’s house in Stamford Hill, and then in my partner’s studio in Holborn, where it sat quietly gathering dust through waves of lockdown and ‘working from home’ dictates, then to a newly rented flat with a bigger front door. It has now found a more permanent place in a Dalston studio where I rent a desk space. The irony that an object typically associated with the rooted and fixed nature of domesticity was so difficult to find a home for has not been lost on me.

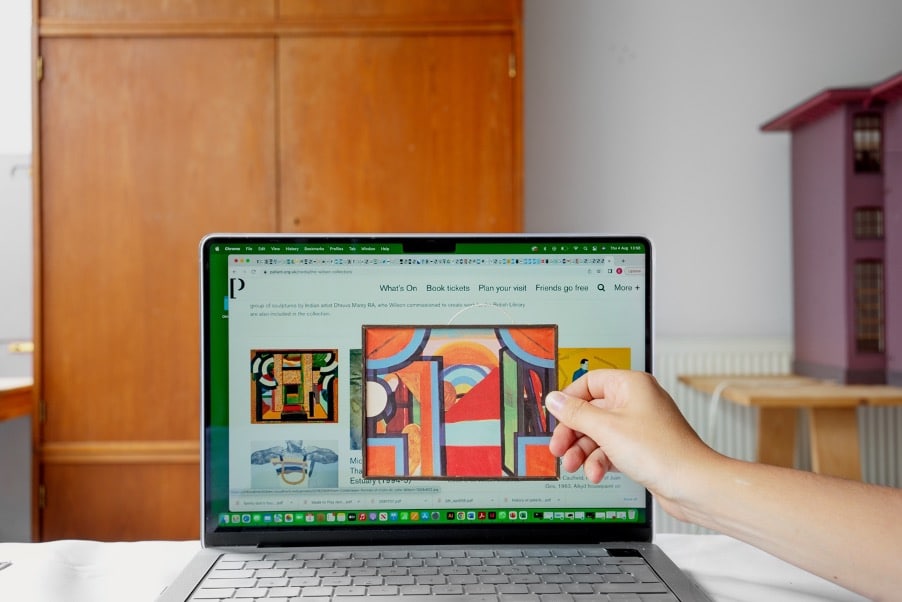

During the pandemic and thereafter, I researched further into MJ Long’s work, looking for any clues that might enlighten the history of the doll’s house. I was fortunate that Sal Wilson, Long’s daughter and, as it would turn out, the ‘client’ for the doll’s house, responded to my requests to talk. Sal explained that the auction house had been reluctant to include it as part of the auction, that they didn’t think people would be interested in buying it. This was partly true, of course, given that I was the sole bidder, but among the contested or rejected objects was also a round wooden table that I remember from my visit to Long’s studio/house—it was where we sat when I first met her. Perhaps it was unmemorable in design, but it had a rich family history, being the locus for many conversations, memories and visitors. Sal had one particular recollection of a dinner party at her parents’ when James Stirling almost caused the table to collapse from an attack of laughter. The background of the doll’s house, though, proved less prosaic. It had, as the description in the auction lot suggested, been modelled on a villa in New Haven, on a street called Hillhouse Avenue, close to Long’s alma mater, Yale University. During one of our Zoom calls, Sal shared the screen to guide me on Google Street View, pointing out the house that was the source of her mother’s inspiration. What I had originally thought was a strange colour choice for the doll’s house exterior, the almost purple-grey and mauve, immediately came into focus on screen. It was peculiar to see the real-life likeness of the doll’s house in this virtual way, and we spoke about why Long might have chosen this house in particular. Perhaps it remained as a fragment in her memory, a house she admired on her route to class each day. Maybe the act of remaking it in miniature form would serve to tie her back in some small way to her country of birth. Regardless, Sal remembers the feeling that the doll’s house was less of a gift to her, and more of a passion project for her mother, one that she worked upon tirelessly in her spare time. Aside from the design and construction of the shell, itself a large undertaking, the interior and contents were nearly all conceived and handmade by Long. A miniature book entitled ‘Sarah Jane’s Alphabet Book, ABC’ bears Long’s handwriting (Fig.1), as does the art collection that hangs inside the rooms, themselves a partial facsimile of Long and Wilson’s own collection (Fig.2). The interiors are covered in various patterned wallpapers, the floors dressed in timber, and miniature ceramic tiles are laid on to the porch (Fig.3 and 4). Windows are hinged, and walls are openable. An electric plug, far beyond safe testing, connects to various lamps throughout the house made from dissected ping-pong balls. It’s a curious thing to look at, seemingly worlds away from the work that Long did as an architect.

This sense of misbehaviour, of something not quite fitting, prompted me to keep looking. I was aware that MJ Long’s personal papers and work were being stored at the RIBA as part of the Colin St John Wilson & Partners archive, to which I have been able to start making regular visits since January 2022. It is from here, with the generous help of one of the project archivists at the CStJW archive, Josie Sommer, that I have embarked on a study of the life and work of MJ Long as framed through the doll’s house.

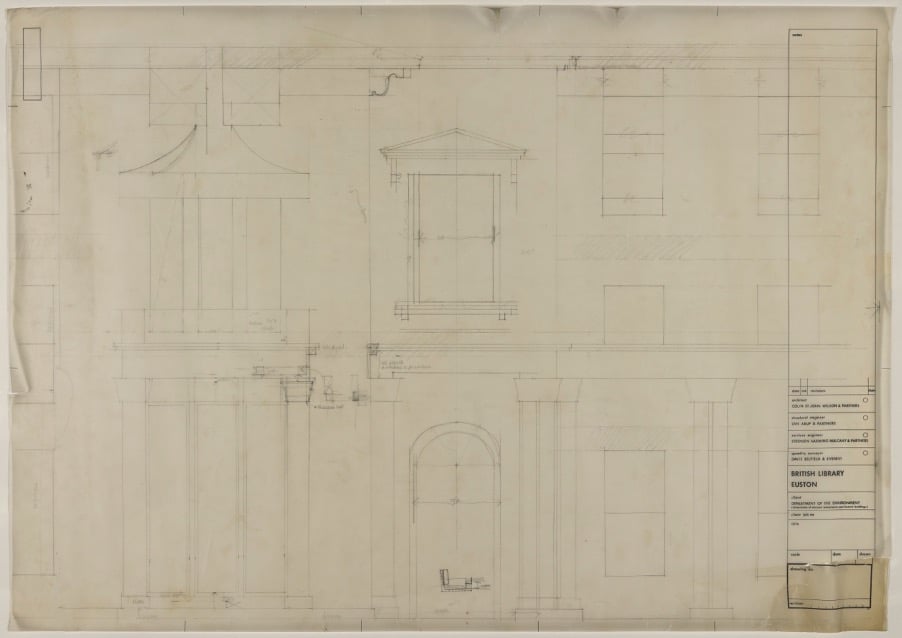

Nearly all of her work is uncatalogued and, as a result, is in danger of being subsumed into Wilson’s, which could be seen as simply a continuation of the gender issues that obscure her contribution to their shared practice in life. What was more surprising, however, was to find out that the construction of the doll’s house took place in the late 1970s at a particularly fraught stage during the design of the British Library, probably their most renowned work. Despite the professional anxiety that they both were surely experiencing at that point, Long devoted any free time she had to constructing this large timber object in the living room that she shared with her two children and husband.

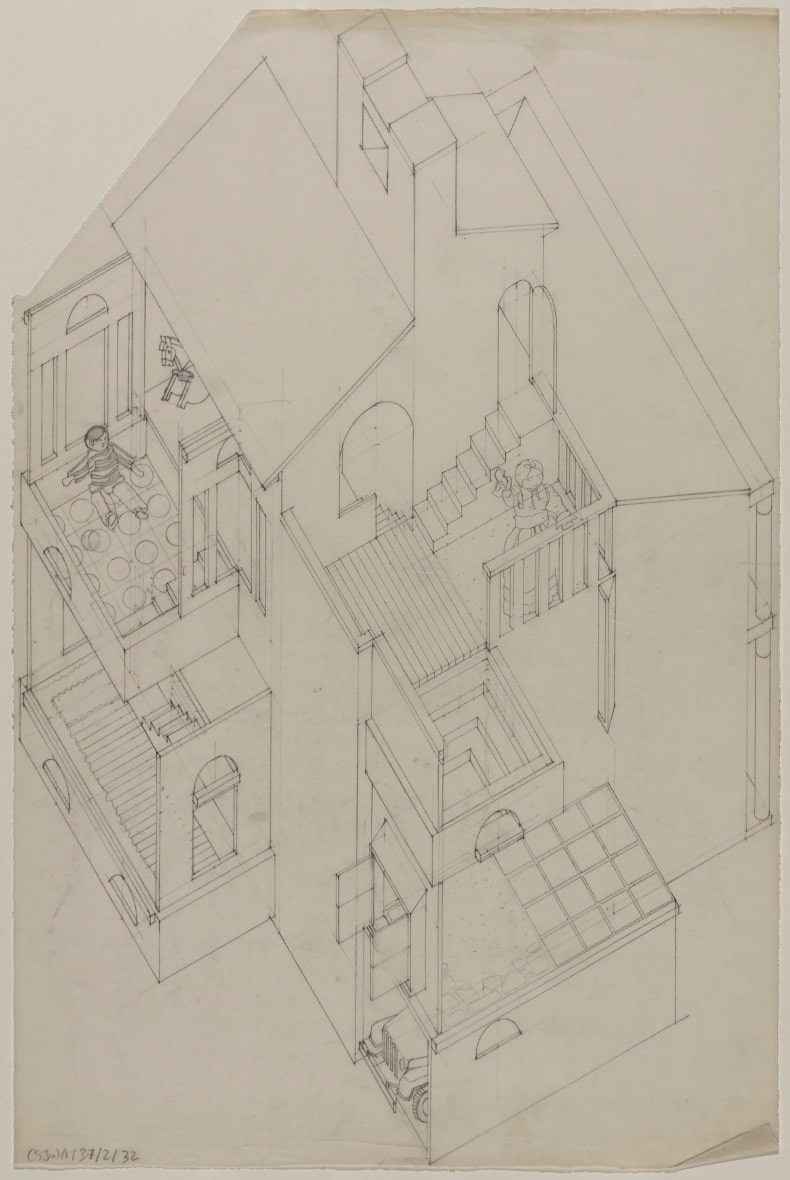

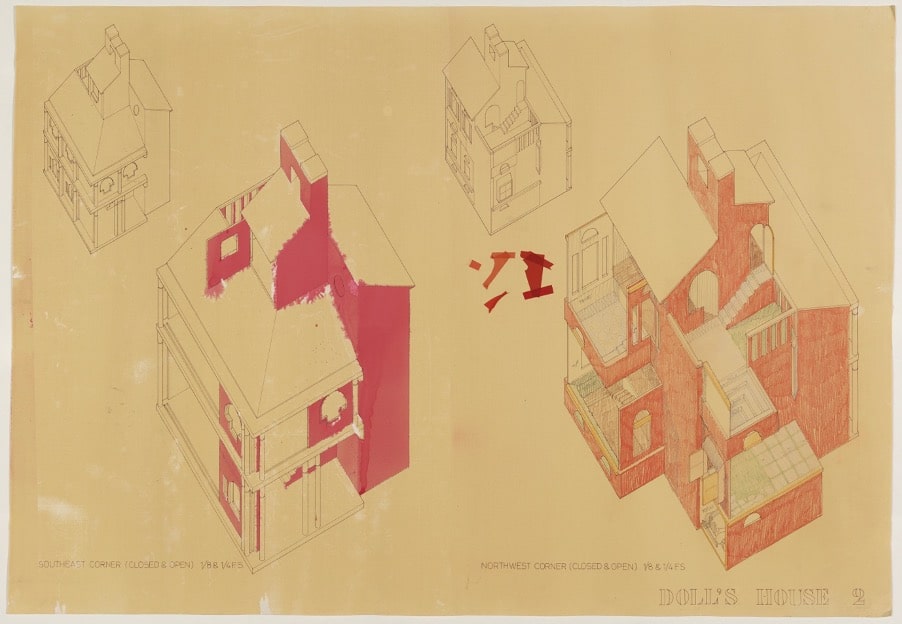

I knew that I might encounter many red herrings when searching the various boxes at the archive, given that Long and Wilson had designed and constructed another doll’s house for a competition run by Architectural Digest magazine (Fig.6). The drawings for this house, which was much more in line with their practice output, were present within the archive and there is a little information in the public domain about this work. But it was one box, labelled ‘Doll’s House SJW’, indicating Sal’s initials, that promised that information existed that would explain the doll’s house now in my care. Contained within was a full set of drawings, much of them made in pencil using a headed architectural drawing sheet from The British Library (Fig.5). Despite the implication, these sketches were not produced for anyone but herself: they are informal, rough and largely without notation—there are some noteworthy overlaps between them and the drawings Long and Wilson made for the AD house. Indeed, I think it’s likely that the work on both was being conducted concurrently. Some of the characters that populate Sal’s doll’s house appear in the illustrations for the AD competition entry (Fig.7), and the colour tests are remarkably similar (Fig.8). Examining both structures, it is also apparent that both objects derive much of their ornament, form and spatial logic from the American Villa type, from which Long repeatedly drew inspiration throughout her career.

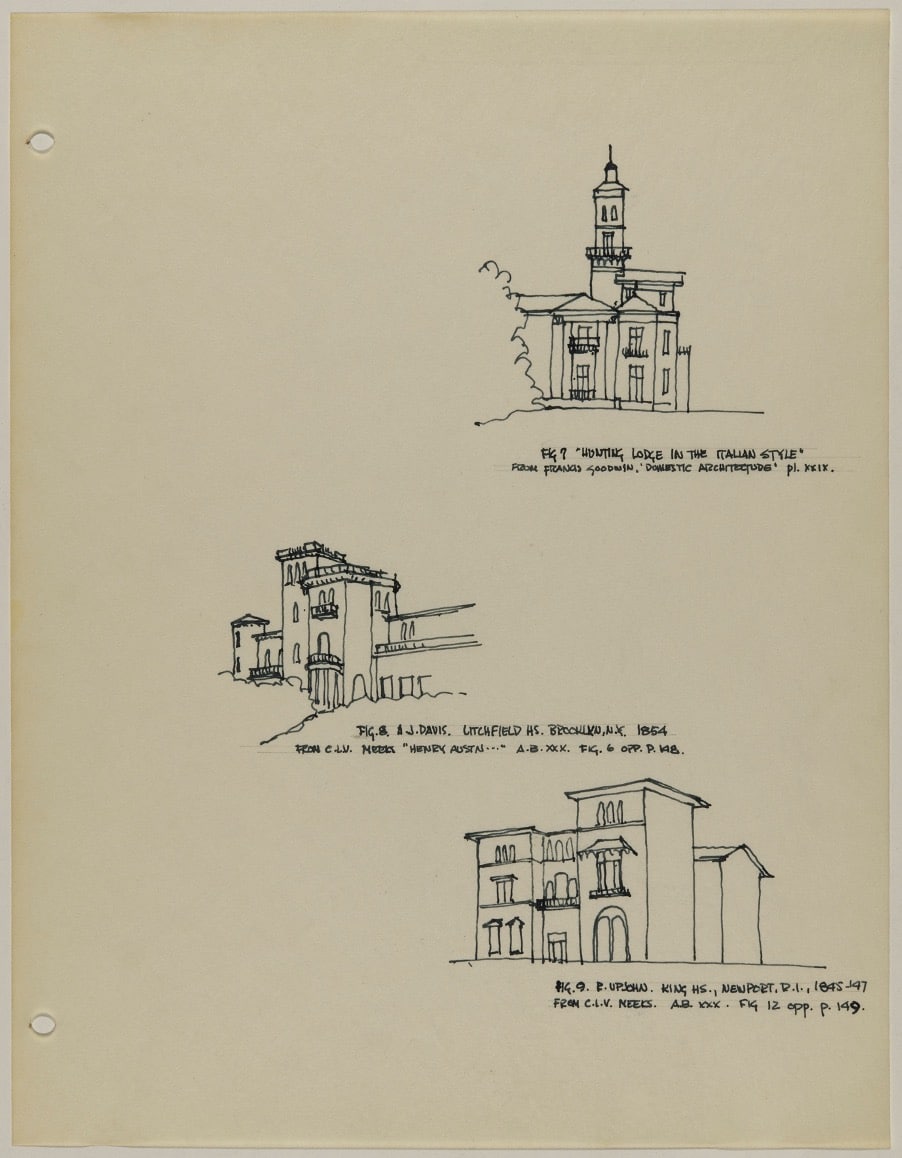

Her interest in the villa can be traced back to her formative years at Yale, where she began her training as an architect. Examining MJ Long’s work as a student there, I found one of a series of essays she wrote about the early-nineteenth-century architect Henry Austin (Fig.9). The resemblance one can draw with Long’s preoccupations and his work, and other residential architecture from New England, is clear in the structure, layout and decoration of the doll’s house. I’ve often speculated that while the work on the British Library will surely have seemed so protracted and drawn out, the construction of the doll’s house must have appealed to her with a clear beginning and end. Naturally, the production feels like an act of care and nurture for her daughter, but the sheer size of the thing constantly reminds me of the physical labour and effort required to bring it into being. It was probably cumbersome, awkward, and heavy. But it was also something upon which she could work independently, late into the night, conjuring ideas and memories into being.

I’m still working on a project to help archive some of MJ Long’s life and work via the doll’s house, and many questions still remain. But the work has started to bring a number of things into focus for me. Much of this is centred around the question of how architectural historiography is written, and therefore how the architectural profession at large is defined, which has traditionally focused on the idea that architects are individual producers of buildings, works attributed to sole authors. The reality of practice teaches us otherwise, of course, but nonetheless recent histories and research on the work of women has tended to frame it with much the same lens, defining their output under the canonical framework of architecture, to which they were anyway restricted access in the first place. While much of MJ Long’s practice was shaped and developed under this framework (indeed, much of her work is indelibly linked to that of her male counterparts), I would argue that her practice ranged beyond the work she did in the office. Perhaps the doll’s house, with all its gendered complexities around the roles and representation of family, is an invitation to us to consider what constitutes work. As an object made outside the conventional territories of work, in the ‘free time’ of its author, it prompts us to think about what we include when we talk about someone’s practice, and the lives of those who make it.

Note

Special thanks to Sal Wilson, Josie Sommer, Barbara Campbell-Lange, Manijeh Verghese, Lola Lozano. Thank you to Jon Lopez for his close reading and suggestions on this text and to RIBA for funding part of this research.

– Editors