N.B. These Drawings Were From Memory

After entering Smart’s Place, and climbing the steep staircase of treads (that become increasingly high and shallow until all the tension in my body was focused on my toes gripping and my weight not leaning back*), I arrived at the space of Drawing Matter where Rosie had indiscriminately laid out materials relating to furniture on a table, about 3 meters long—curving with the earth—like a buffet. My attention was mostly taken by the three-dimensional objects. Prisms, domes, wire frames, plaster casts, and cardboard boxes. So, the one three-dimensional thing that I could make out on the buffet table without looking directly, was a large plastic box. It must have been about 300 x 300 x 250mm. Semi-transparent, milky plastic, with hinged blue handles. There was a sticker in one corner presumably referring to its archive location. I thought that I should wait to be introduced. I didn’t know how this worked.

I was then introduced, in order from right to left—if looking at the table from the direction of the door to take advantage of the natural light coming in from the opposite window—to one piece from the archive at a time. I got to know Superstudio’s illustrations, Ponti’s Aria, Vittorio Valabrega, and other equally mysterious concepts. All things I knew little—if anything—about.

But that milky resin container kept wanting my attention. It had a vibration of a human timbre calling me to look at it.* Just once.

It was a plastic box with the barcode and cubic capacity still stuck on it. No discrimination here.

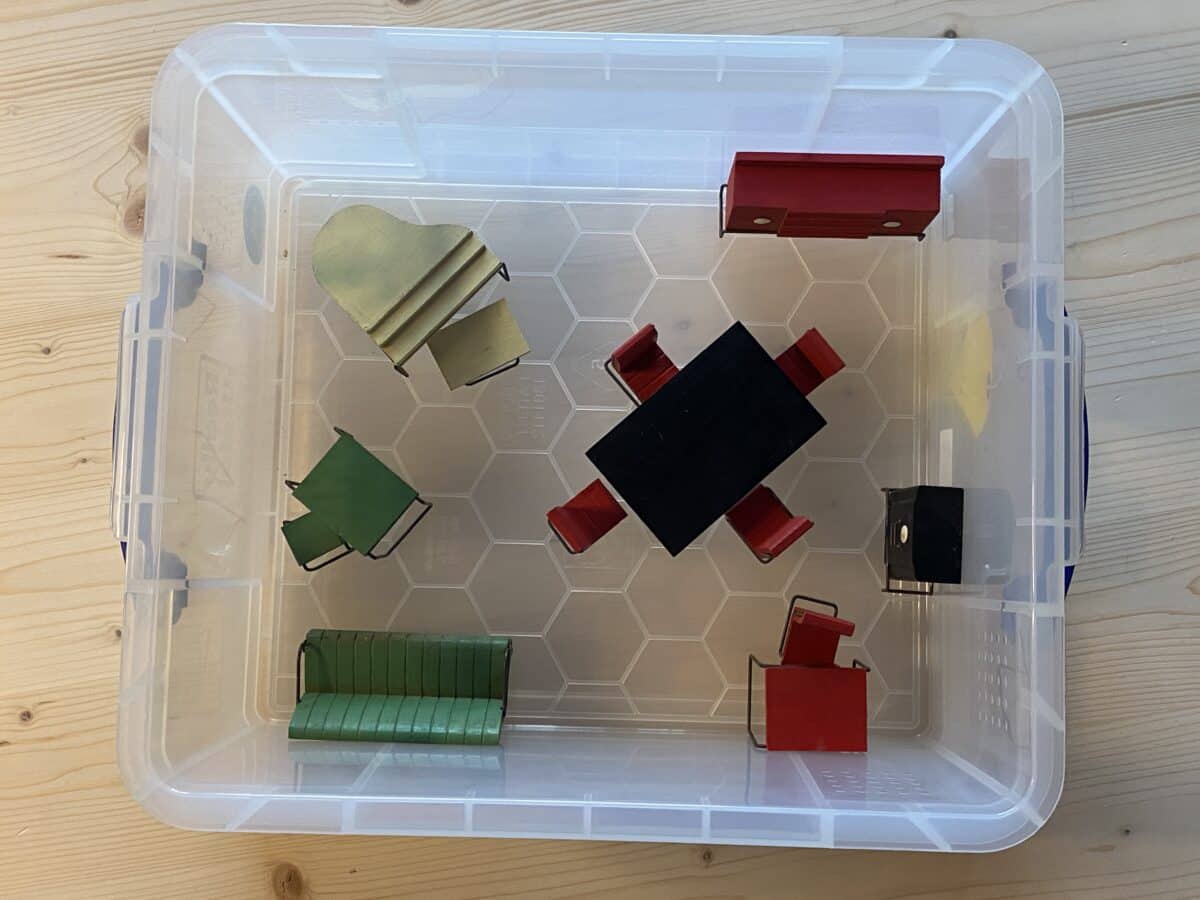

I peered inside, at what now seemed like a doorless room containing furniture… sized for dolls. Apparently a short-lived production from about 1936-37 by John Lloyd Wright—son of Frank—the furniture of four colours is unified by one feature. Modernist preoccupation from between the wars: tubular steel. The frames of the furniture are not tubular, but solid, and clumsily attached underneath to balsa wood components with staples: a cream piano and stool; a red desk and chair; a red sideboard; four red dining chairs around a black dining table; a black radio; a worn green double sofa; and a small green table with a box stool.

I put the piano back down in the room, and heaven forbid anyone that lives in there should be megalophobic, seeing my hand reach in and change their furniture around.

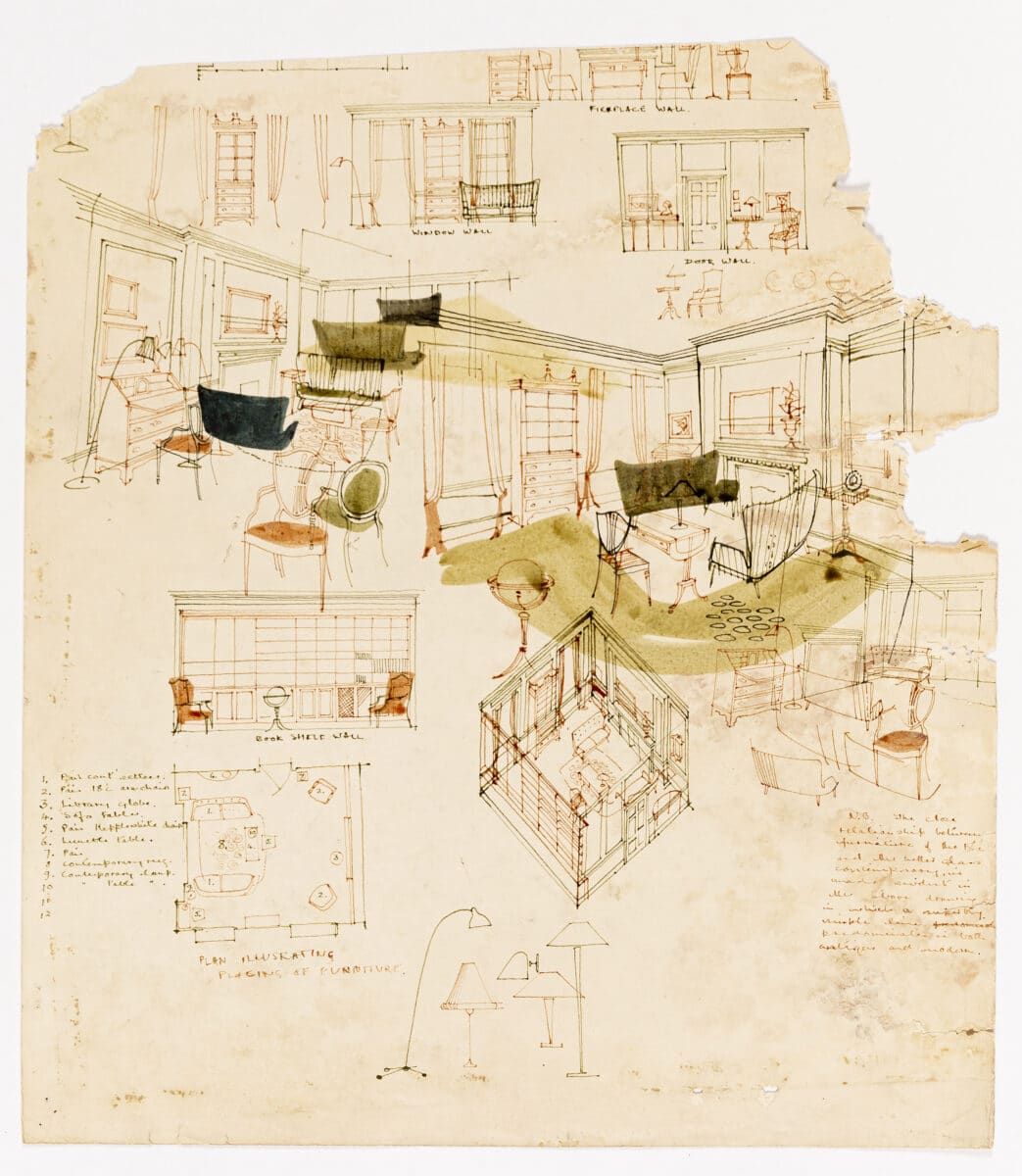

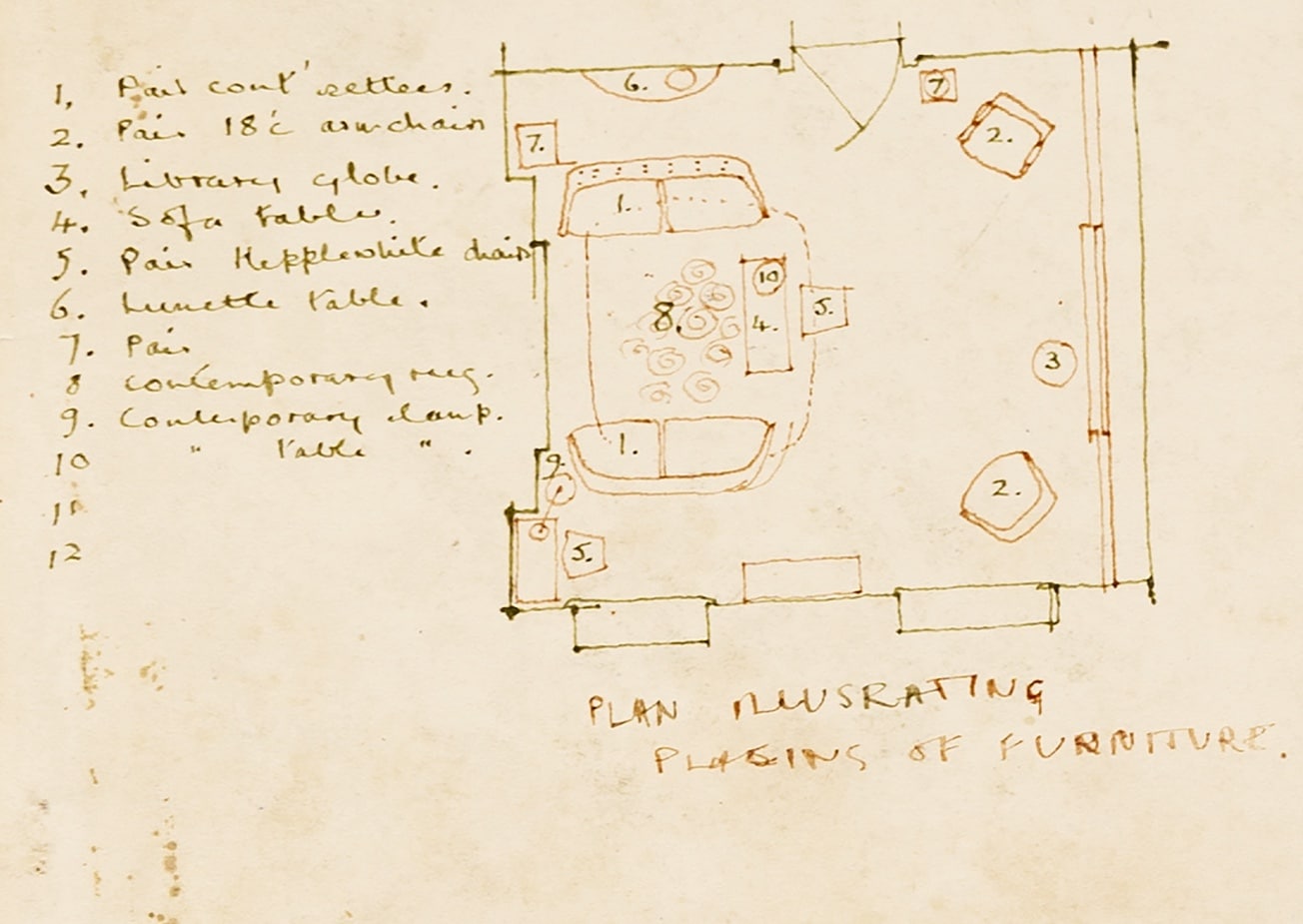

Another piece at the table had a list of contents:

PLAN ILLUSTRATION PLACING OF FURNITURE

1. Pair cont’ settees.

2. Pair 18c’ armchairs

3. Library globe.

4. Sofa tables.

5. Pair Hepplewhite chairs.

6. Lunette table.

7. Pair

8. Contemporary rug.

9. Contemporary lamp.

10. “ table “

11.

12.

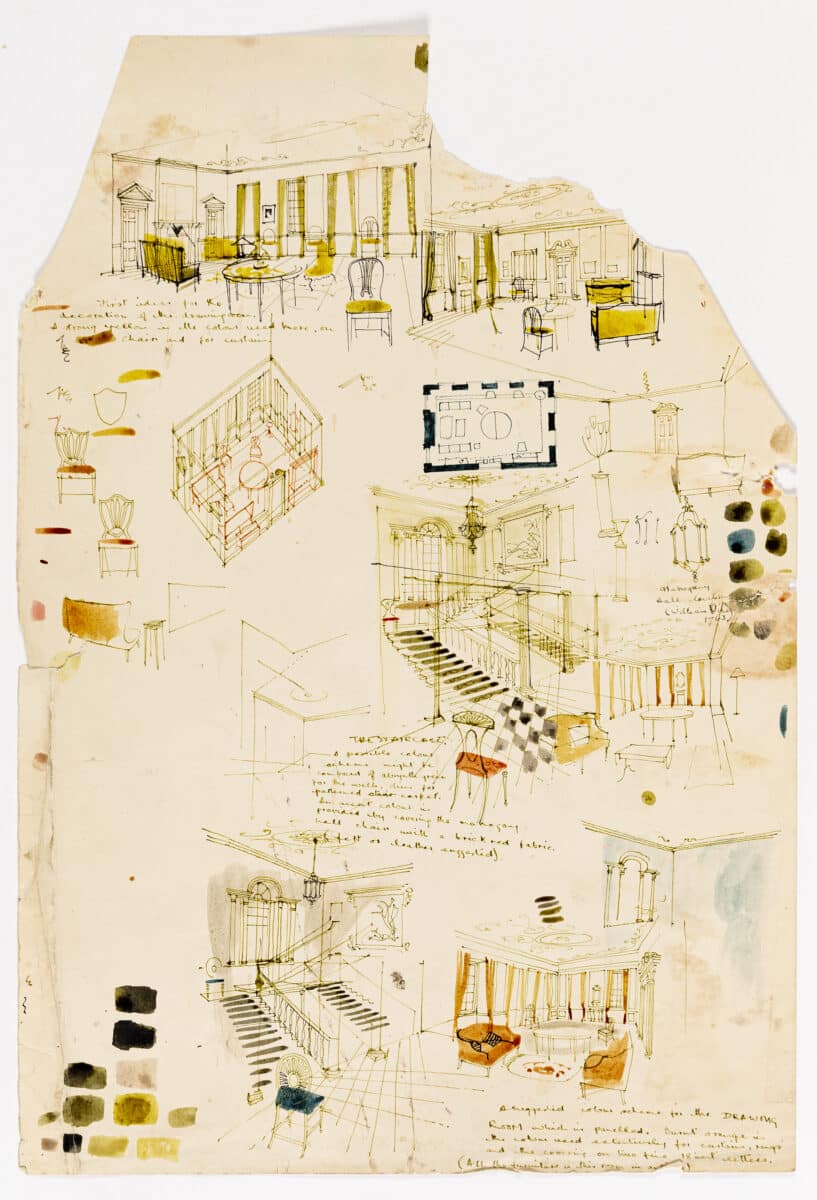

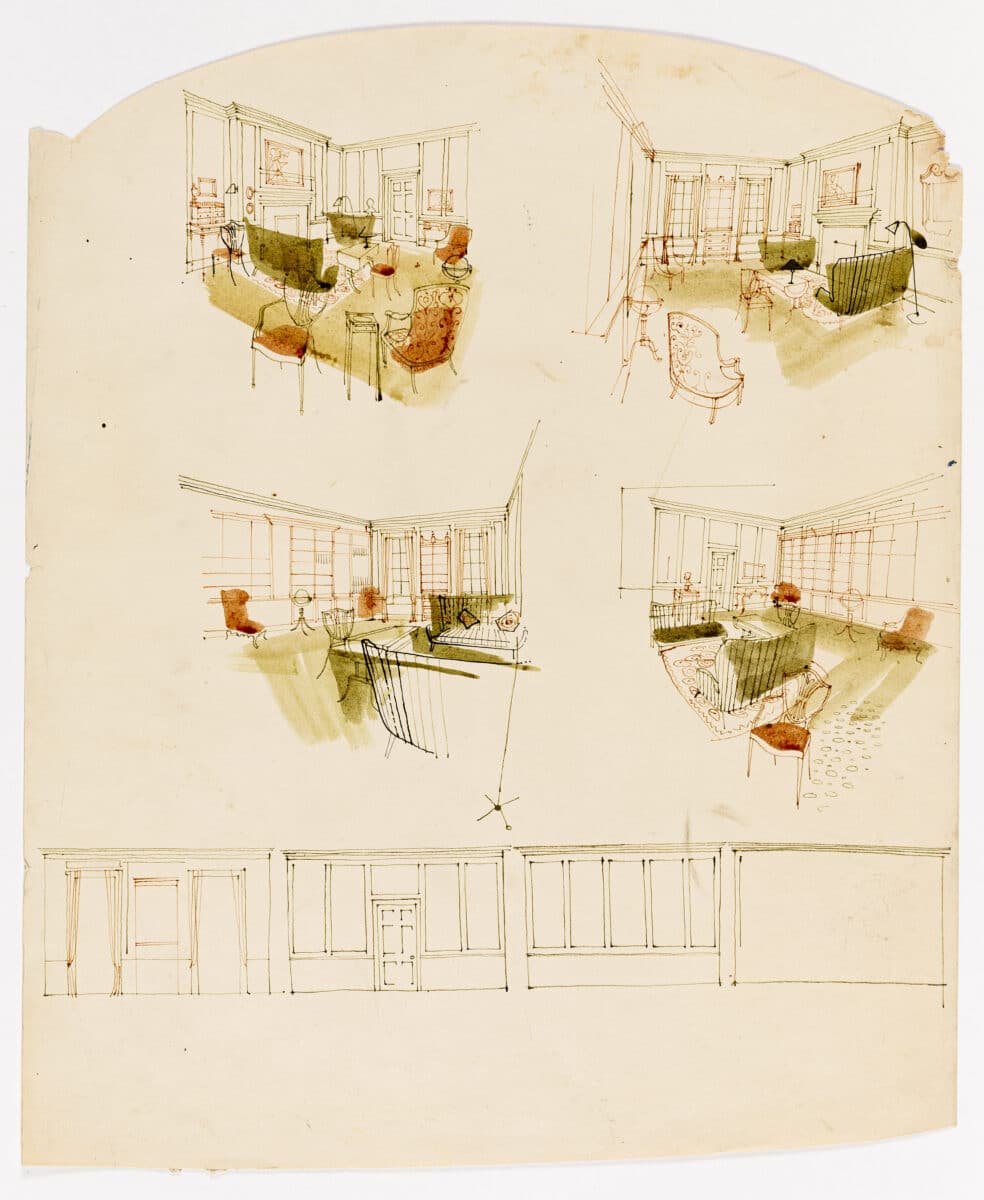

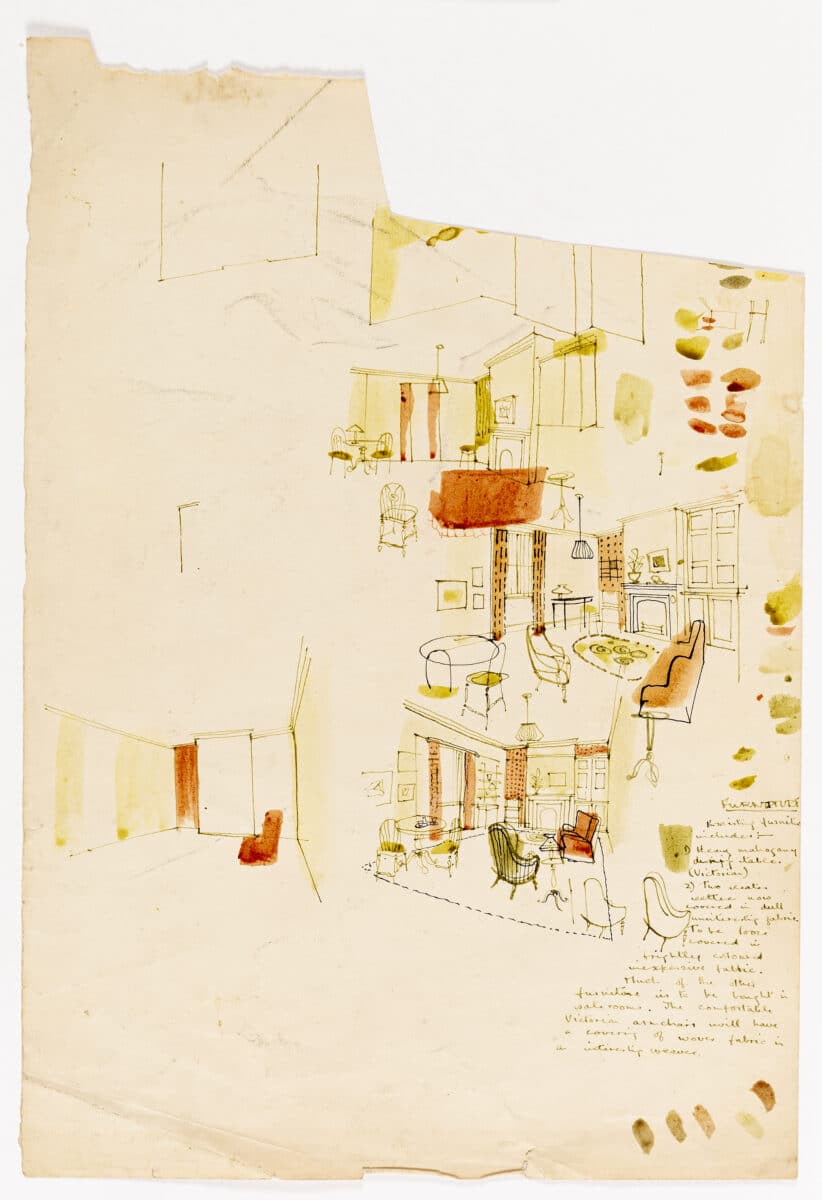

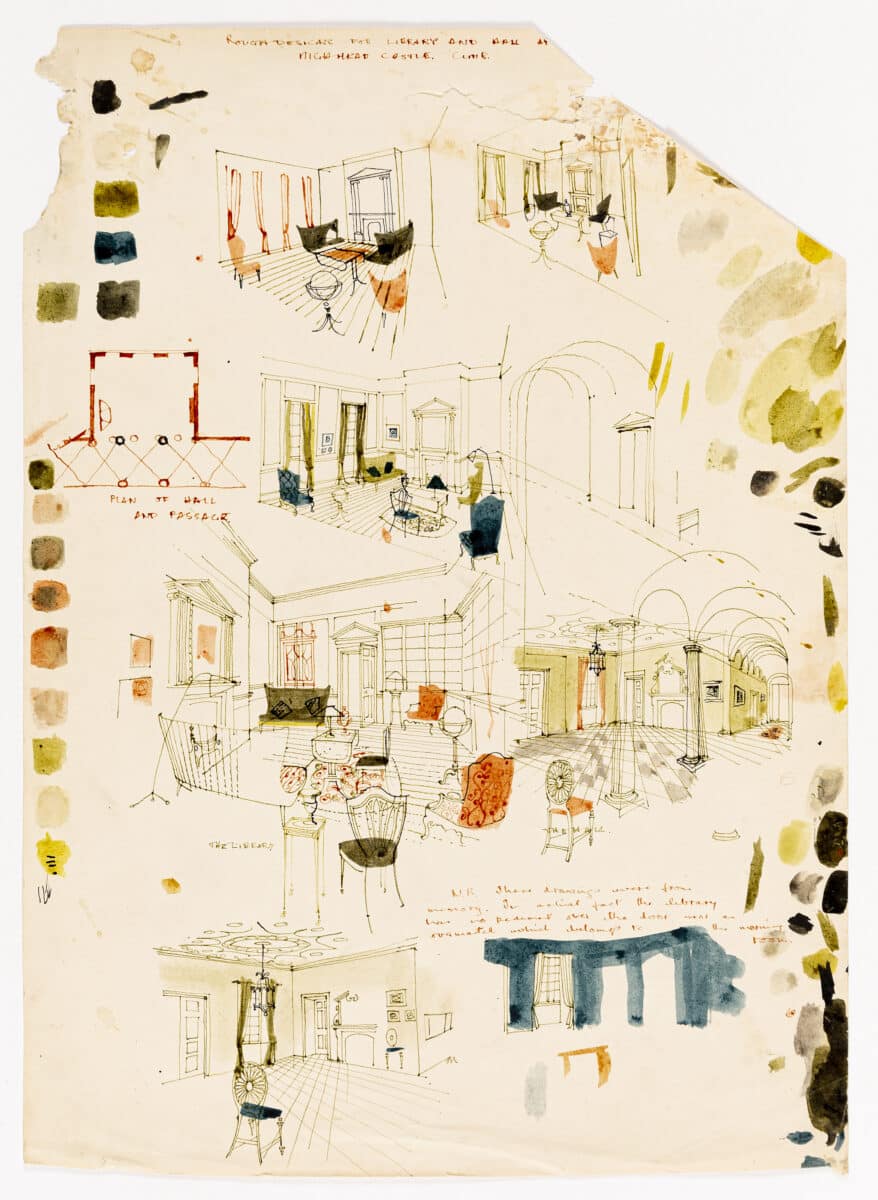

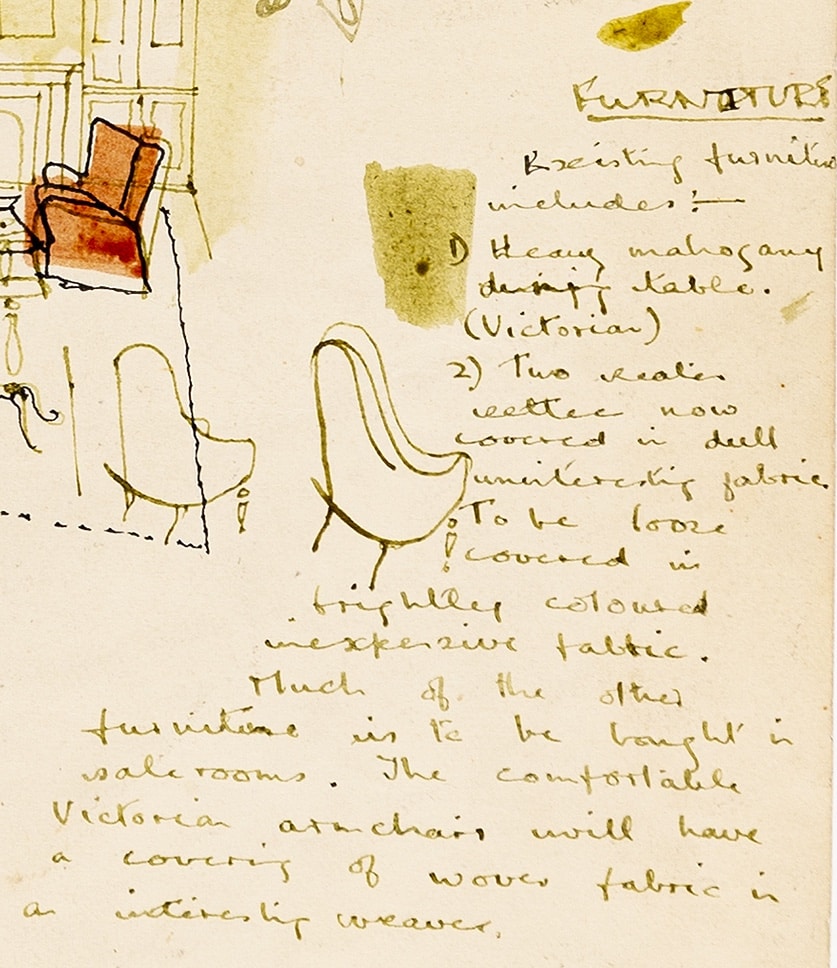

It was part of a floor plan, precisely scribbled in a corner of one page of a set of five drawings, in a deep olive-coloured ink. Though it did not relate to the Wright living room for doll sized people, it was an interior design project by David Hicks—a decorator renowned for his colour, practicing between the 1950s and 1980s. His drawings for HIGH HEAD CASTLE. CUMB were spread out on the far left-hand side of the table. High Head Castle, in Cumbria (an English manor with some of its architecture dating to 1272, but other parts to the 16th and 18th century) was gutted by a fire in 1956 and was never brought back to life. Just one portion of it survives and it’s certainly not the portion that we see in Hicks’ drawings. Presumably, his visits and scheme were made before the fire because he makes no mention in his scribbles of a post-traumatic rebuild. Only materials, colours, and furniture. The drawings have been done quickly by someone with incredible skill. His notes for the space were all over the drawings.

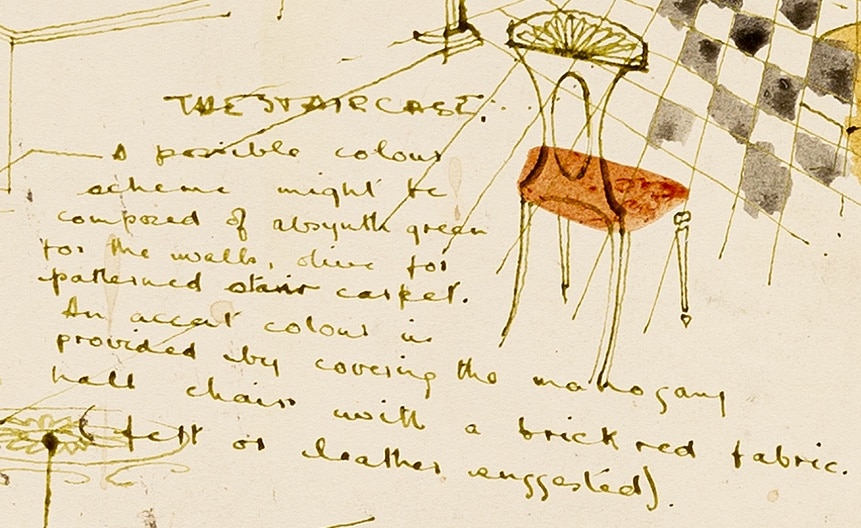

Though ‘possible’ and ‘might be’ suggest an uncertainty, he moves quickly to bold colours, like ‘absinthe green’ and ‘brick red’ in one sentence. These question marks reserve his humility.

A possible colour

scheme might be

composed of absinthe green

for the walls, olive for

patterned stair carpet.

An accent colour is

provided by covering the mahogany

Hall chairs with a brick red fabric.

(Felt or leather suggested)

The descriptions tell us what we need to know. From lavish patterned carpet to ‘brightly coloured inexpensive fabric’. His decisions are justified in these pages—financially and conceptually:

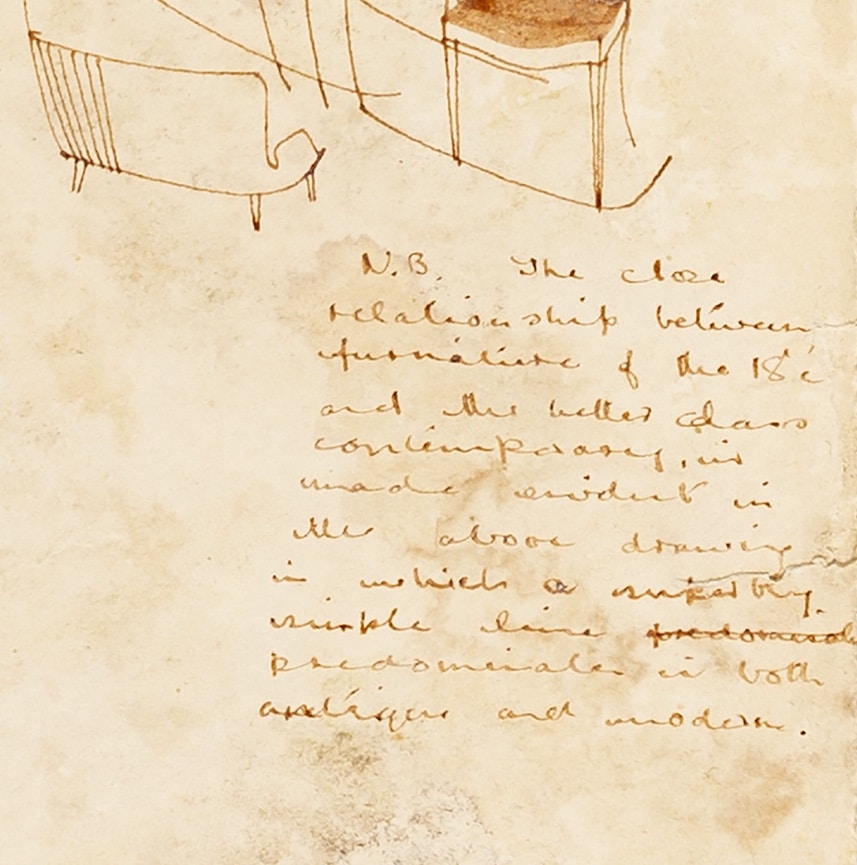

N.B. The close

relationship between

furniture of the 18 C

and the better class

contemporary is

made evident in

the above drawing

in which a [illegible]

visible linepredominates

predominates in both

antique and modern.

I think he is getting at the flared, wing-backedness of the 1950s sofas bouncing off the shapes of the Hepplewhite Chair and 18th-century sofas, as do the slightly sabred back legs of the other contemporary pieces.

At what stage of the project these would have been created, I don’t know.

He writes:

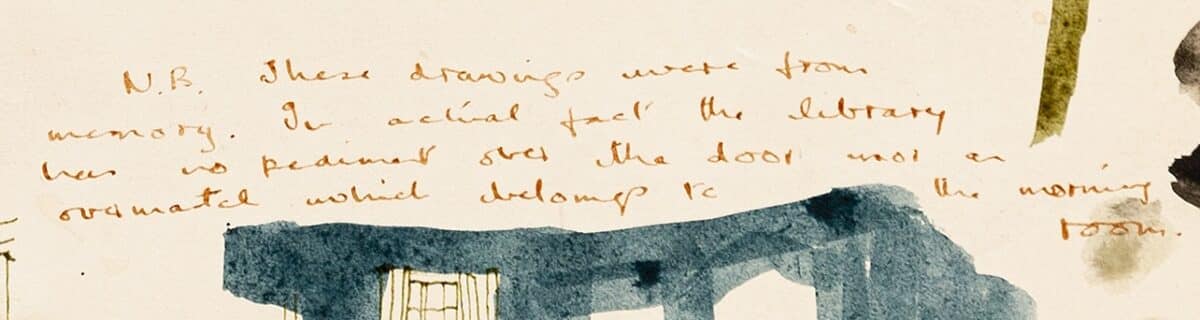

N.B. These drawings were from

memory.

Memory was holding it together. Getting back to his studio, after a site visit no doubt he had the idea to draw the space with some new ideas.

Then back to the site, and for all his divine inspiration, his memory failed him.

In actual fact the library

has no pediment over the door nor an

overmantel which belongs to the morning room.

The layers of the drawings show the number of times he has revised and revisited. There’s an overlaying and more acute axonometric drawing of the room on this page. On another, four angles of the same room in an almost fisheye, POV perspective, detailing the groin vault, columns, curtains.

One page is more chaotic than the rest of the set. It is made harmonious, however, in its eloquent colour palette and execution. There are a few samples of soft furnishings made with brushed orange ink, and fine-lined chairs drawn around them in varying degrees of development. One just a back, one now with front legs, and a final form with the beginnings of back legs too—all drawn in elevation. His tools mark the edges of the paper as he tries his best to accurately represent the colours in his mind. Oranges, pinks, indigo, olives. Sounds like a salad I’d usually swerve.

I peer down the buffet again to see if I missed anything before leaving.

There are other things aligning, but I hear, again, the call of the plastic box… tempting me to rearrange its furniture with the free will of Hicks on his pages. I moved the piano one more time.*

*Some details may be exaggerated for effect.

Abel Sloane is a dealer and collector of materials relating to furniture design. His primary focus is the innovative concepts of the twentieth century however, a need to research the roots of such innovation has created wider interests that pre- and post-date the Modernist period.

– Emily Priest