Sir John Soane’s Museum: Bound Legacy

John Britton, a topographer and antiquarian by trade, began preparations to publish a guidebook to John Soane’s house-museum in 1825. The earliest mention of such an endeavour appears in a letter to Soane dated 3 November, in which Britton outlines his desire to ‘produce a vol to surprise the public, and even to satisfy you and myself’. Just over half a year later, Britton writes to Soane once more outlining his progress and asserting that his efforts will yield an ‘interesting and curious volume’ that will ‘perpetuate [John Soane’s] name when [his] buildings are levelled to dust…’ Britton was resolute, and his ambitious guidebook would serve a multitude of purposes.

In 1827, The Union of Architecture, Sculpture and Painting, with Descriptive Accounts of the House and Galleries of John Soane was published. The first of an ongoing lineage of guidebooks to the house-museum, the publication is comprised of ‘descriptive accounts’ of the series of interiors, a treatise on interior architecture, and an essay outlining Soane’s collection of architectural casts, drawings, paintings and books. 22 various engravings, including plans, sections, elevations and views of Soane’s interiors encompass the volume’s illustrative component.

Britton’s guidebook did not sell, and ultimately Soane was not satisfied by the work, as indicated by the publication of the first of his own line of Descriptions only three years after Britton’s volume. The interim period between their respective publications was one of turmoil for their relationship, both personally and professionally.

Scholars have argued that Britton’s published accounts of Thomas Hope’s country seat, the Deepdene, as well as William Beckford’s Fonthill Abbey, provoked Soane to entrust Britton with the responsibility of creating the first published aid to his collection. These previous volumes conform well with Britton’s topographical oeuvre, often featuring a traditional, unadorned ground plan of the galleries for navigational purposes, as well as a selection of interior views of the traditionally hung collections of drawings and paintings. The Union of Architecture, Sculpture and Painting differs from these more successful volumes, and the genre of nineteenth-century guidebooks.

The ingenuity of Soane’s arrangement of space has been explored by the likes of Jas Elsner, Wolfgang Ernst, Susan Feinberg, Helene Furjàn, Robin Middleton, Donald Preziosi, Sophia Psarra and Margaret Richardson; the thread of commonality that binds their texts are the ‘kaleidoscopic’ and ‘labyrinthine’ and ultimately Soanean qualities of the built form. Similarly, Robin Evans acknowledges Soane’s spatial complexities in his essay ‘The Developed Surface’ (1989): ‘Soane’s architecture…broke through walls to achieve real and extended depth… To attempt to illustrate deep spaces expanding out from a room represented as if it were a flattened paper box was plainly futile.’ Evans’ essay explores the unique qualities of Soane’s spaces that the laid-out elevation drawing convention is incapable of capturing. Arguably, Britton’s literary brief was obscured by such spatial perplexities, and in addition, the multi-categorical nature of John Soane’s house-museum; domestic home, public gallery, architectural academy and professional studio.

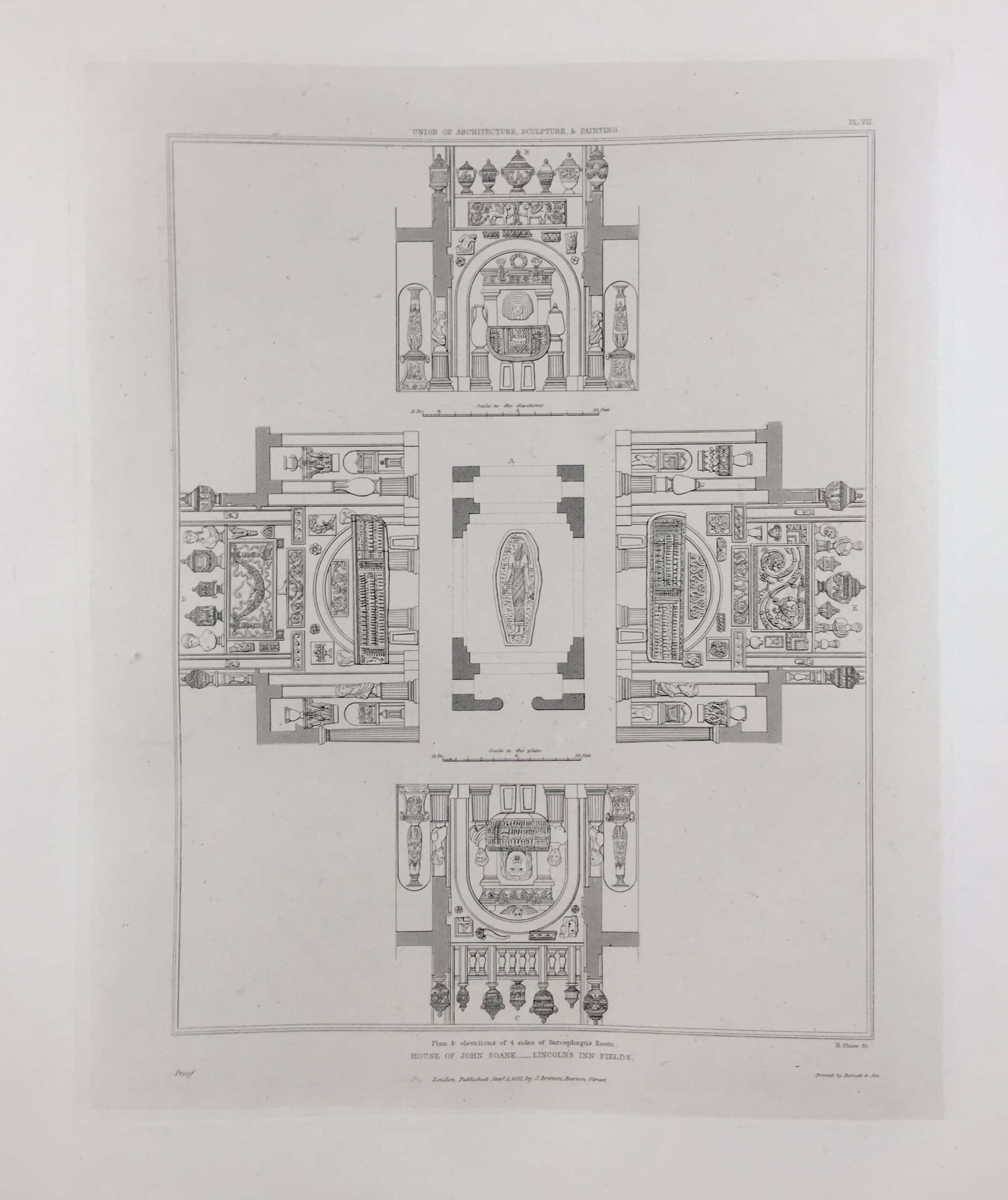

To illustrate Evans’ findings on the laid-out elevation, this engraving reflects the object-centric nature of Britton’s publication. The ‘elevations’ [and sections] of the ‘Sarcophagus-room’ are arranged radially around an image of the sarcophagus itself. The bases of the walls surrounding the sarcophagus are delineated in poché, however, the sarcophagus itself is stamped with the image that has been inscribed into the bottom of the interior of the object – like a horizontal section, the inscription of Seti I revealed through the sectioning. The presence of walls that have been ‘broken through’ are very much evident in the hint of a floor plan encircling the sarcophagus – however, the depth they achieve has been lost in this flattened depiction of space.

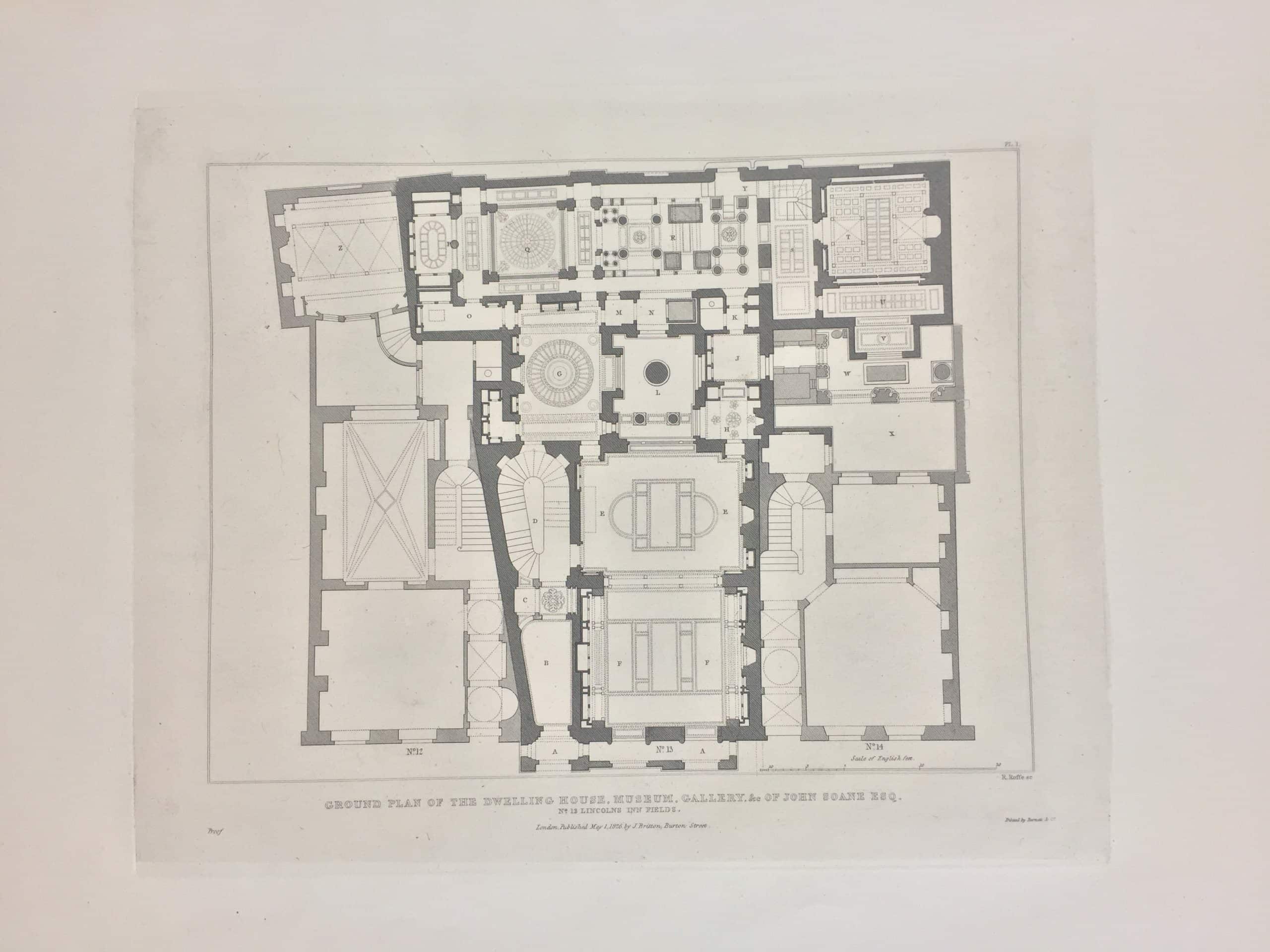

Much like his more successful publications, Britton employs a ground plan of the house-museum, asserting that ‘by referring to and studying the annexed plan, the reader will be able to obtain an accurate idea of the forms and arrangement of the ground floor…’ Having volunteered at Sir John Soane’s Museum for a number of years, I am familiar with the labyrinthine nature of the arrangement of space and its associated navigational difficulty once inside. Despite the distribution of this ground plan to visitors, requests for navigational aid did not cease.

The plan is inclusive of elements of a reflected ceiling plan, including a collection of hanging decorative features; the overlit dome in the Breakfast Parlour (G), the hanging pendentive arches in both the Library and Dining Room (F) and Picture Room (T). The same can be said of the plaster roses on the ceiling at the Entrance Hall (B) and the Dome (R). The ‘Pasticcio’ in the Monument Court (L), rendered as a dark sphere, is firmly categorised as an object within Soane’s collection – an assemblage of architectural fragments – rather than supporting structure or masonry. Decorative objects are ubiquitous throughout Britton’s volume, evoking the intangible rather than a pure objective representation of the architectonic form of the built fabric itself, which is also rendered as poché. The reader/visitor is imparted with architectural epoché; entering the house-museum void of expectation and equipped with this ground plan as a means of navigating Soane’s spaces, it is these decorative features that suggest something abstract – a sense of wonder, an archive of architectural history, the embodiment of its primary domestic inhabitant.

The task of representing the built form in a publication is reductive in both the selection of two-dimensional images to represent the three-dimensional structure, as well as the translation of the built form to textual description. The physical qualities of the book itself present further constraints, particularly in comparison to more loose, fluid manifestations such as sheets unbound in a portfolio.

Although the physical nature of a book provides limitations, within these limitations is the potential for creation; the creation of a sequence, and an implicit meaning within such a sequence. Within a guidebook such as The Union of Architecture, Sculpture and Painting, this sequence manifests as a prescribed route for the visitor. Additionally, the arrangement of certain illustrative conventions in pairs might be more premeditated than simply following the order in which Soane’s apartments have been presented in the accompanying text.

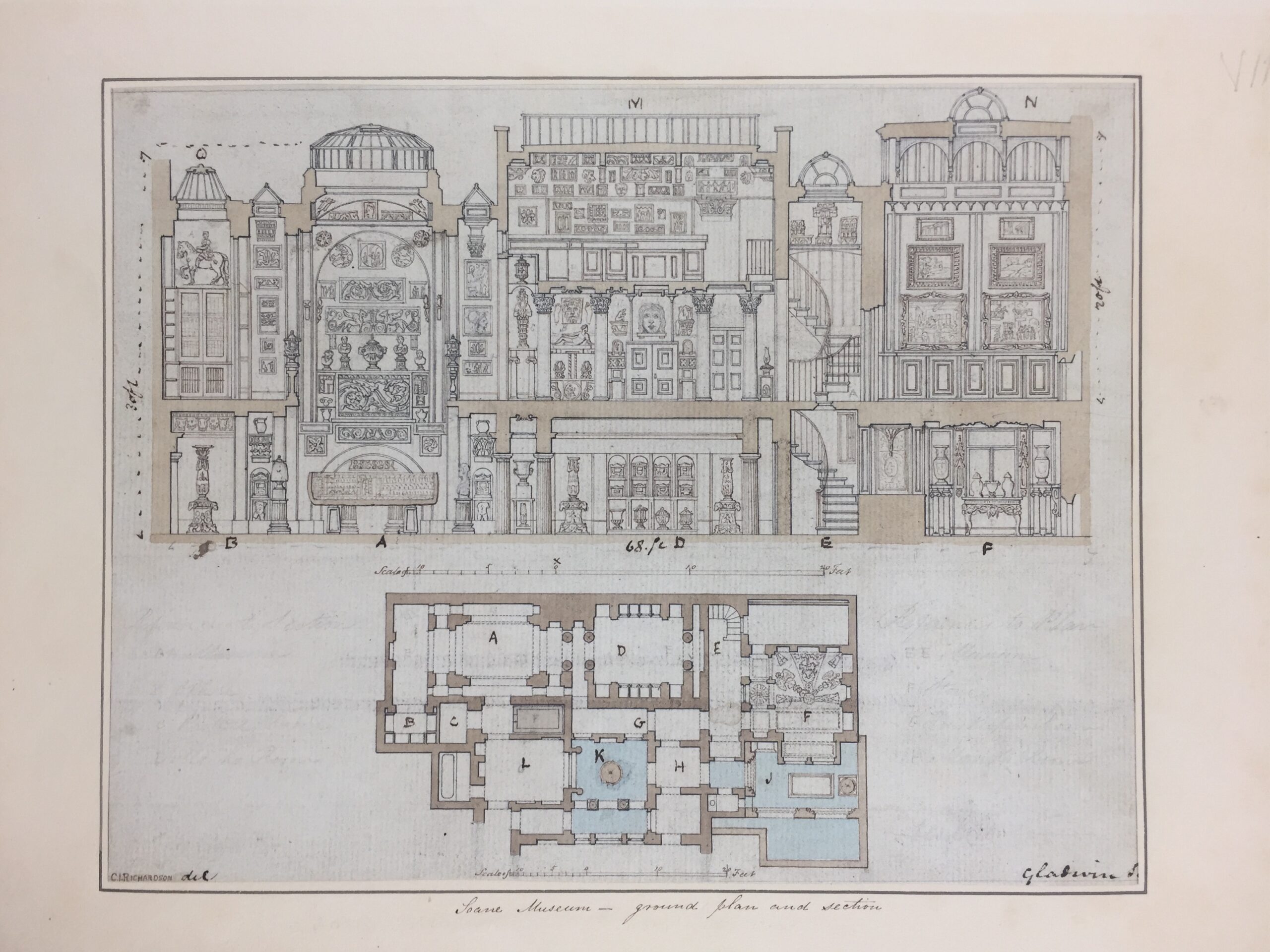

With the inclusion of other ground plans presented in conjunction with sections, like this Section of Museum, Gallery, Offices &c., the reader/visitor is prompted to combine the two and mentally ‘construct’ the three dimensional form – a process explored by Evans in The Projective Cast (1995) and Alberto Pérez-Gómez and Louise Pelletier’s Architectural Representation and the Perspective Hinge (2000). Britton’s arrangement of these components simplifies this process, the bottom edge of the section and the top edge of the plan serving in conjunction as the perspective hinge.

The concept of the arrangement of multiple representational methods in sequential order, or even within the same page, is arguably as meaningful as the manner in which Soane arranged his museum; the fixed nature of the book elicits permanence, a table of contents solidifying this physical order within the text thereby eliminating the potential for rearrangement after publication – a bound legacy. Fundamental to the house-museum is the idea of safeguarding one’s legacy through a tailored archive; this archive can be understood as the primary documents, such as his correspondence with John Britton in his library at 14 Lincoln’s Inn Fields, or further, his collection and its unique arrangement, preserved by his 1833 Act of Parliament.

‘[T]he real houses of memory, the houses to which we return in dreams, the houses that are rich in unalterable oneirism, do not readily lend themselves to description. To describe them would be like showing them to visitors.’ At the heart of Bachelard’s phenomenology of the house is the experience of the inhabitant represented by the congregation of fragmentary images. Similarly, the illustrations in Britton’s volume are reliant on memory. Bachelard’s parallel between the arrangement of a house and one’s ability to contemplate and visualise is comparable to John Britton’s arrangement of his guidebook and the ability of the public to synthesise and imagine the memory of Soane’s house and collection.

Britton’s arrangement of visual material deviates from what one might expect from a nineteenth-century guidebook. The publication does not aim to serve as a total objective representation of the building fabric itself, despite the methods of representation employed that might suggest otherwise. With this limited scope of knowledge being conserved, the act of resurrecting the house-museum once ‘levelled to dust’ is rendered impossible. Ultimately 14 of Britton’s engravings were used in Soane’s own description of his house-museum. 17 of the survey drawings and views used for the engravings, by the hands of C.J. Richardson, Edward Davis and Henry Shaw, can be found bound within a small paper, quarto issue of The Union of Architecture, Sculpture and Painting , SM Drawings Vol. 84, Sir John Soane Museum collection reference 6614.

Postscript: Collector’s Memorandum

Almost a decade and a half after the failed volume, the lineage of the Soane guidebook persists, the house-museum very much in-tact.

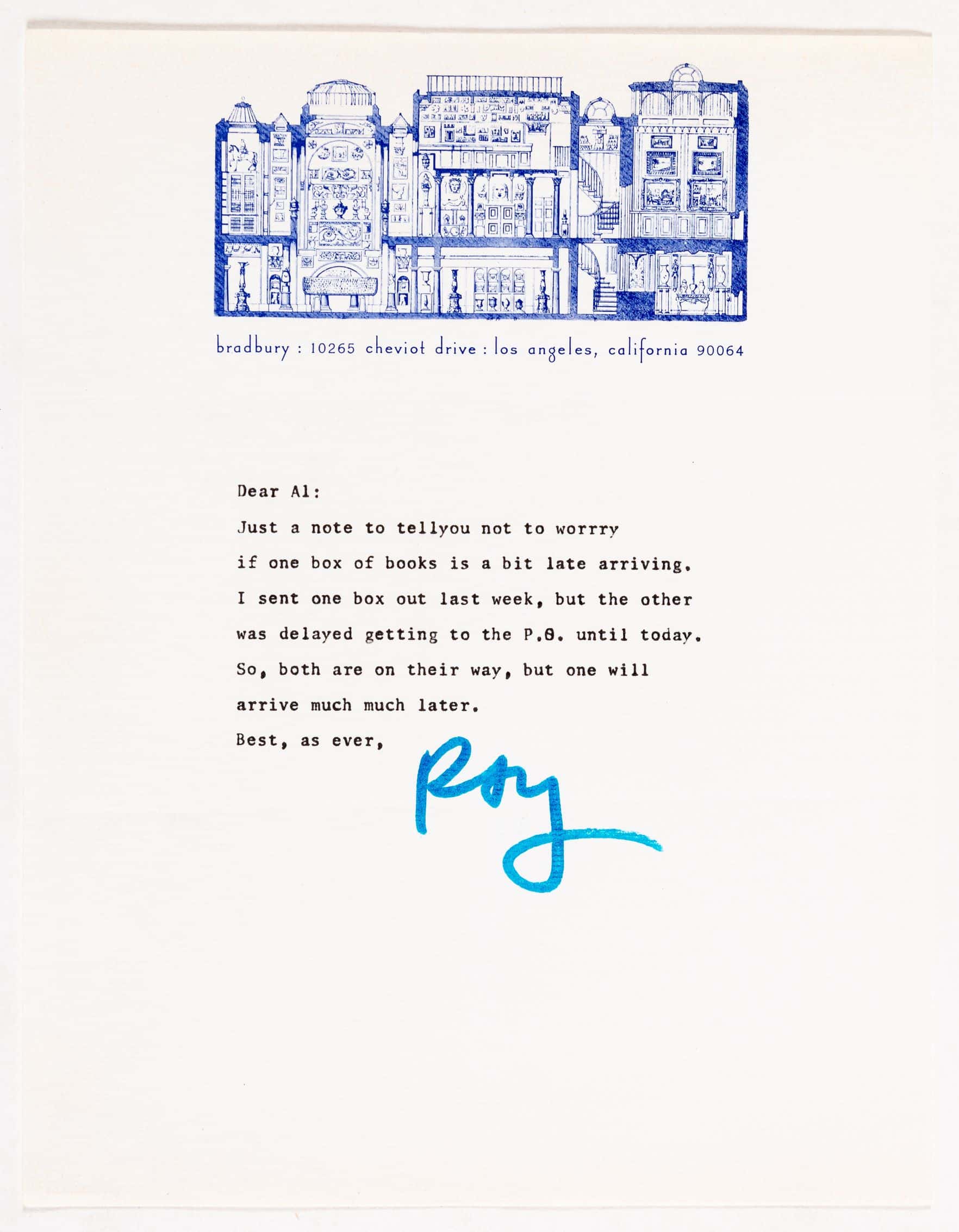

Meanwhile, friends and acquaintances of Ray Bradbury were forgiven for assuming the section at the top of his letterhead depicted his own home in Los Angeles. The American science fiction novelist and screenwriter acknowledged the misgiving in his 1991 collection of essays Yestermorrow. In ‘Go Not To Graveyards, Seek Me at Soane’s’ (1987) Bradbury explains, ‘I have used Soane’s digs as my letterhead for some fifteen years.’ He outlines his wish to reside in the upper levels of the ‘vertical tombyard’, to be buried there – ‘[y]ou see that Egyptian tomb, lower left? That’s it. File me there, with bread and onions, for eternity!’ – such fandom is perhaps unsurprising considering Bradbury’s eccentricities, as well as his own infamous basement. His poem focusses on objects within Soane’s collection, and largely reads like a catalogue raisonné. Noticeably absent is any mention of the building fabric of Soane’s ‘digs’.

This section was originally drawn for publication in Britton’s The Union of Architecture, Sculpture and Painting (1827) alongside a ground plan of the basement level of the museum. It has since been reproduced considerably; it can be found in great abundance in the museum gift shop, in the latest guidebooks, printed on tote bags, mugs and dish towels.

It is noteworthy that Bradbury refers to Soane’s museum as a ‘vertical tombyard’, for this is precisely what concerns him – the verticality, the walls of the museum, which are the canvas for Soane’s collection to be hung from. Cropping the ground plan from this depiction is a further testament to Bradbury’s interests. In borrowing the section, Bradbury associates himself specifically with Soane, the collector. Both Bradbury and Soane share an interest in future speculation, for Bradbury in the form of science fiction and the advent of new technologies, and for Soane, the future of his own architectural legacy – best summarised in Crude Hints towards an history of my house, an unpublished manuscript written in 1812, in which Soane imagines a future antiquarian discovering the ruins of his house-museum.

Alexandra received her PhD in Architectural History from the University of East Anglia, and an MA in History of Art from the Courtauld Institute. She currently works at Haworth Tompkins.

This text was submitted in the long form category (1000-1500 words) of the Drawing Matter Writing Prize 2020.

– Pierre du Prey