Studio Mumbai: Saatrasta-Mahindra Tape Drawing

The idea of using tape drawings originated for climatic reasons: India goes through a five-month monsoon season each year, and during this time it is very humid. For us this meant that the drawings we were producing, which were printed on paper, had a very short lifespan. Lines would slowly start to blur, becoming difficult, if not impossible, to read, and eventually the paper would come apart.

In an effort to find a solution, some of the carpenters came to me proposing plywood as an alternate medium, as it would respond better to the humidity.

I was initially hesitant, arguing that plywood was undoubtedly going to be more expensive than paper. They showed me, however, that the expense of having often to reprint the drawings to replace the old faded ones, combined with the efforts to maintain plotters and printers, greatly surpassed the overall figure we would have been faced with had we been using plywood instead.

So the method was developed in response to a practical issue as well as one of an economy of means: in the end, tape would last, modifications could occur and, most importantly, plywood could be recycled.

This is how we began to use tablets for working drawings of different scales (we use them for drawings in the earlier stages as well), which we make in the studio and which can afterwards be used and stored on site. What was fundamental to me was that there be a tolerance intrinsic to this method, whereby the tablet should function not so much as an instruction, but rather as an instrument enabling anyone to understand what is represented and to apply their own sets of skills in translating the drawing into a physical manifestation.

To this day, having moved from our previous studio in Alibaug to a more climate-controlled office in the city, this method remains in practice, because ultimately the weather conditions haven’t changed.

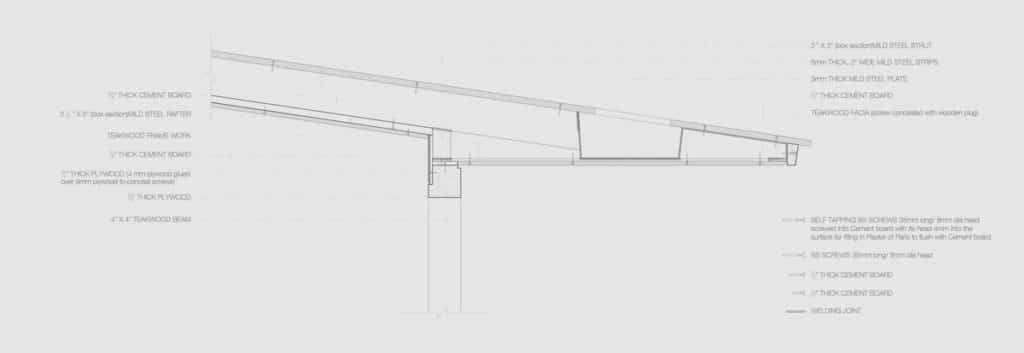

This particular drawing comes from the Saatrasta project and it depicts a section detail of the Mahindra Unit’s roof edge; we are looking at a fragment of the courtyard.

In my buildings I use water, air and light. The importance of these ingredients lies in the fact that if I stay as close to them and to their phenomenological nature as I can, the result is in some way a representation of life and of the environment that surrounds us.

The way I practice, architecture works both on a personal as well as universal level. If we think that what fundamentally makes me also fundamentally makes everyone else, then it means that we are all deeply connected. So each day, when we wake up, we try to locate ourselves at an imaginary centre, a point to which we can relate. This is what enables us to negotiate the best of our day, every day, by pulling in and out.

To me this centre lies in the fundamental connection between earth and sky, and this piece in particular condenses this point of anchorage.