A Civic Utopia Exhibition

A Civic Utopia: Architecture and the City in France 1765-1837 was curated by Nicholas Olsberg and Basile Baudez, and organised by Drawing Matter Trust in collaboration with The Courtauld Gallery as part of Somerset House’s celebration of the 500th anniversary of Thomas More’s Utopia.

The exhibition considered the place of architecture in establishing the notion of public life, bringing together a selection of ideas for public building and public space from the late Ancien Regime to the early years of Louise-Philippe that suggest the ideal of a ‘scientific’ city, in which rational, hygienic and symbolic expressions of civic life established a pattern for the improvement of society.

Porta

Porta looks at the city limits through a series of cabinet drawings that celebrate the metropolitan grandeur of an ordered waterfront (a model followed by William Chambers here at Somerset House); the enjoyment of movement and promenade as open space in the approaches to the city replaced its walls, inhabited bridges, and citadels; and the new dignity accorded to hygienic functions such as hospitals or burial grounds as they moved to its perimeters.

Nicholas Olsberg: This was the largest of the infamous barrières designed by Ledoux in 1785 to enforce the farming of taxes as goods entered the newly walled city. Ledoux had conceived them as classical propylaea, or ceremonial markers of the city’s porta, and Michel’s sketches show them, long after their official purpose had ended, in much that light, moving us toward the city from the its eastern periphery, with its market gardens and country houses, and showing the site as an open space of rest, conviviality and recreation, as the widening route to the country carries the panoply of urban life and traffic, from an empty farmer’s wagon to a coach and carriage.

NO: This huge open square, which became known as ‘Place de la Concorde’ in homage to the idea of reconciliation after the upheavals of the Revolution, was completed in 1775 to Ange-Jacques Gabriel’s designs as part of a vast plan for the embellishment of the city, its expansion to the open land in the west, and the widening of its streets and bridges, exemplified by the extraordinary masonry engineering of the bridge (1786–91) in Fontaine’s view. Gabriel’s largely open square had become a contested site, and in this unbuilt proposal Fontaine presents a carousel and fountain with an essentially neutral classical iconography. Focusing attention on Bernard Poyet’s new façade for the national assembly across the river, on the passage of urban traffic, and on the play of water, Fontaine’s drawing celebrates the vitality of the city square, the bridge, and the rond-point so that a huge monumental ensemble becomes a dynamic parade of urban life, perhaps to demonstrate the civil ‘concord’ it was now named to represent.

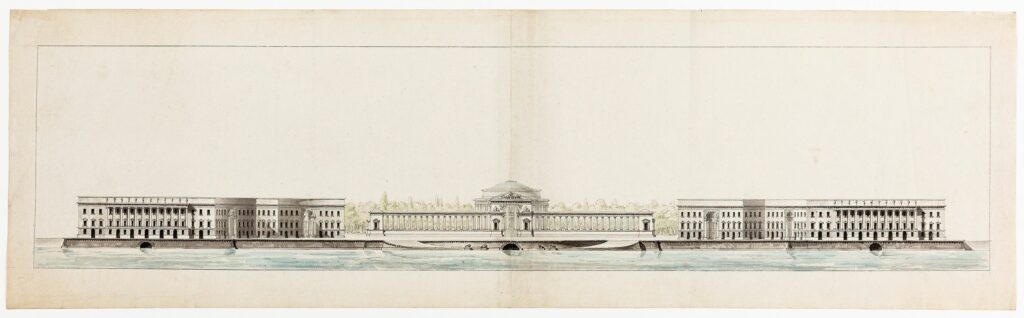

Basile Baudez: Louis Combes, an architect from Bordeaux trained in Parisian academic circles, submitted this competition design for a large square on the river Garonne to serve as a monumental entrance to replace an old fortress, the Château-Trompette, that the government had wished to demolish since the mid-eighteenth century. This porta, evoking a vast Roman antique circus, was intended to host patriotic celebrations, while the green park was to function as leisure space by his fellow citizens.

BB: After large portions of the Paris Palais de Justice were destroyed by fire in 1776, Pierre Desmaisons, member of the Académie d’architecture, rebuilt the entrance court façades and its monumental gate between 1783 and 1786. Wishing to transform the dense and impoverished île de la Cité on which the building stands, he projected, to no avail, a formal public square linking the Palais de justice with the church of Saint Barthélémy and uniting them with a modern façade.

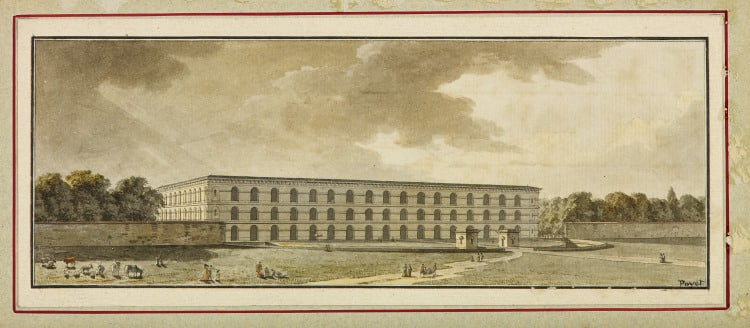

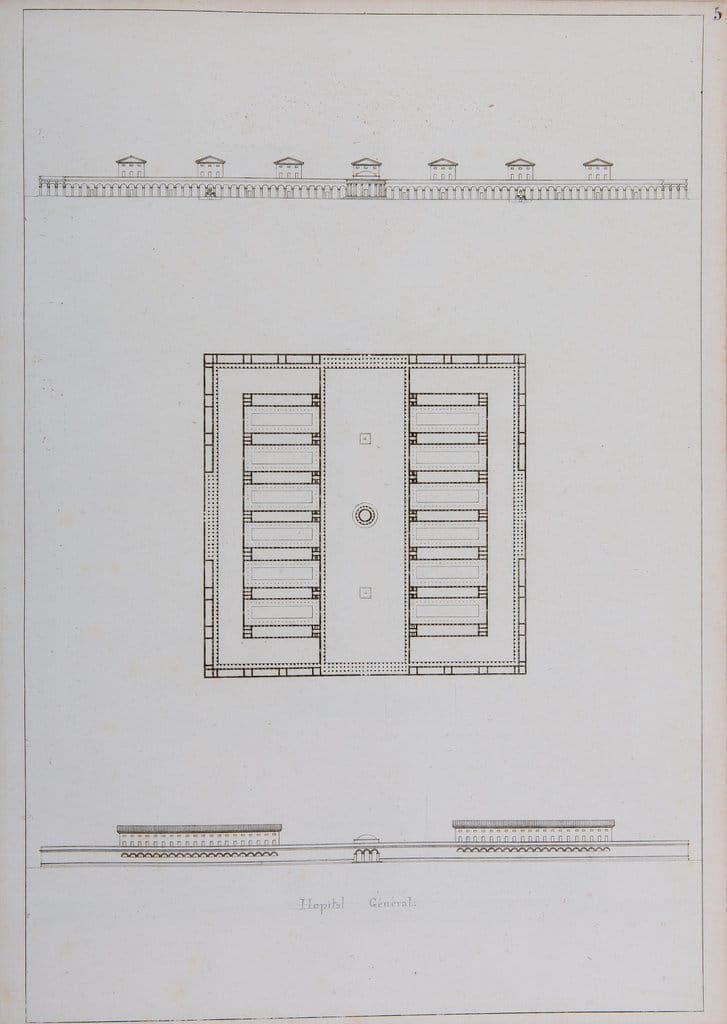

NO: The late eighteenth century saw a broad movement for the reform of the hospital system, in which ideas of comfort, separation, hygiene and cure of the sick replaced that of simply removing the infirm and indigent from society. Based on reports to the academy of sciences of severely crowded and unsanitary conditions in the old public hospital, or hôtel-Dieu, Poyet, the city architect, was commissioned in 1785 to produce plans to replace it, on a more healthful site on the perimeter of the city. His initial proposal for a vast circular building on the river was rejected, but this design for one among a proposed set of smaller hospitals on the city perimeter, perhaps for incurables, followed many of its ideas in rectangular form, including narrow aisles of small chambers, each with an arched window scientifically designed to maximise light and air. Construction was authorised in 1788 but suspended with the Revolution. Poyet revived his circular plan in a later and highly influential publication.

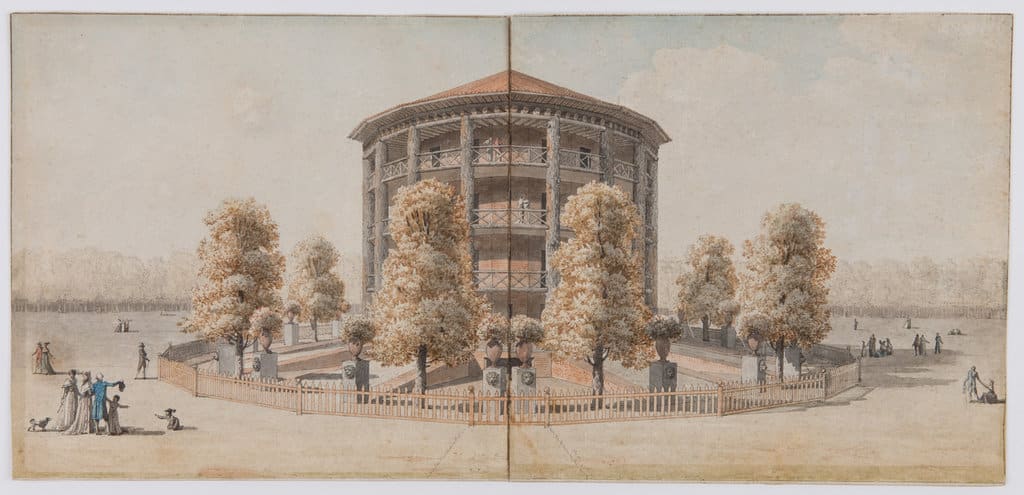

NO: Belanger designed two extravagant parks for great estates on the western edge of Paris bordering the Bois de Boulogne – the Bagatelle for the comte d’Artois and this response by his neighbour the baron Saint-James. Both were ornamented with follies connected by underground passages. This proposal, probably for a menagerie of exotic animals on the public perimeter of the estate near the Champs-Elysees, was presented on two sheets that would have opened to show the scene within.

Lexicon

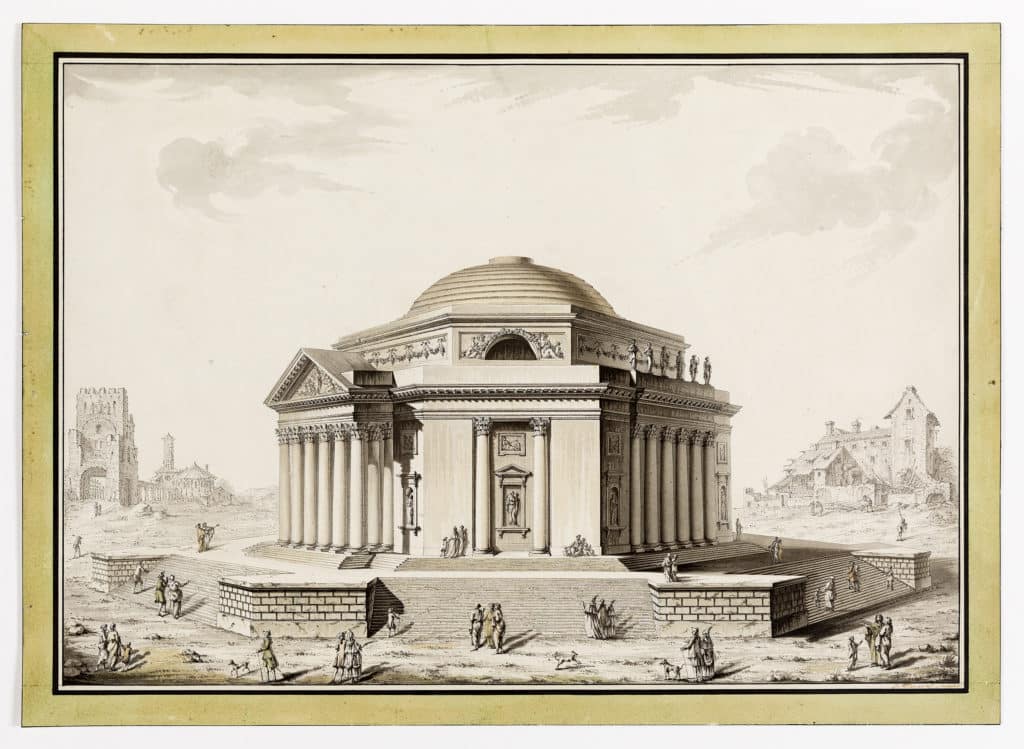

Lexicon presents two examples of the new urban vocabulary, evolving in France from Roman precedents, and of its impact on the world at large — A proposal for a French cemetery in Rome that echoes ancient forms; and a selection of model projects from the circle of the Ecole des Beaux-Arts that show the distinctive language developed for the different building types of a secular, civil society.

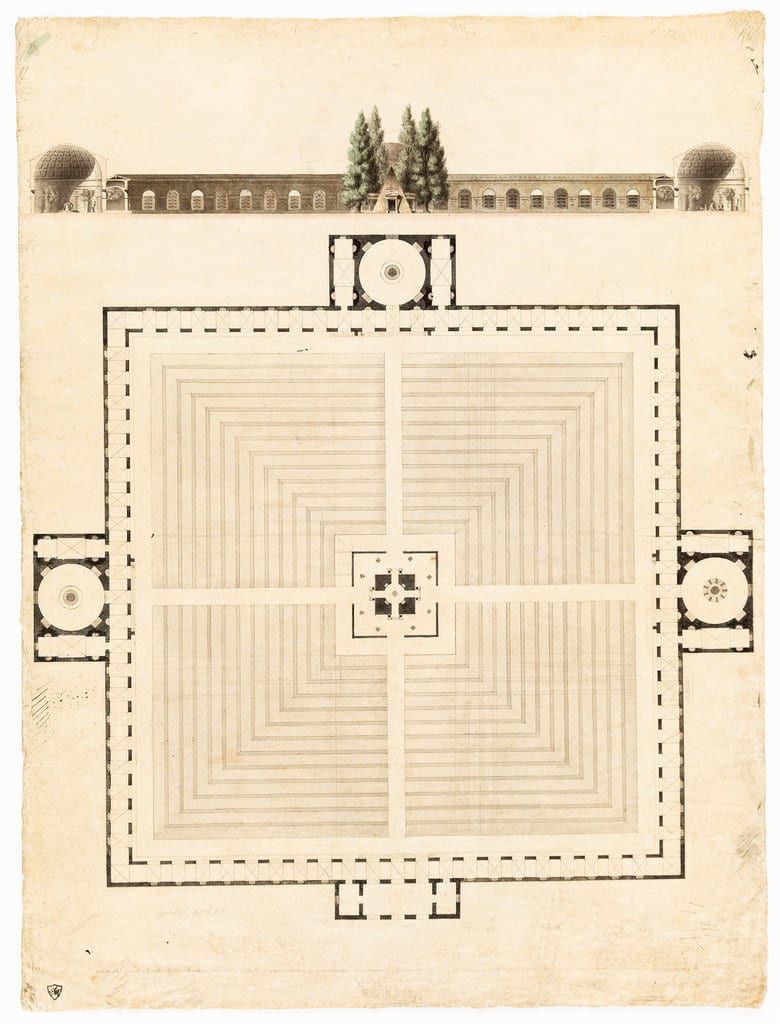

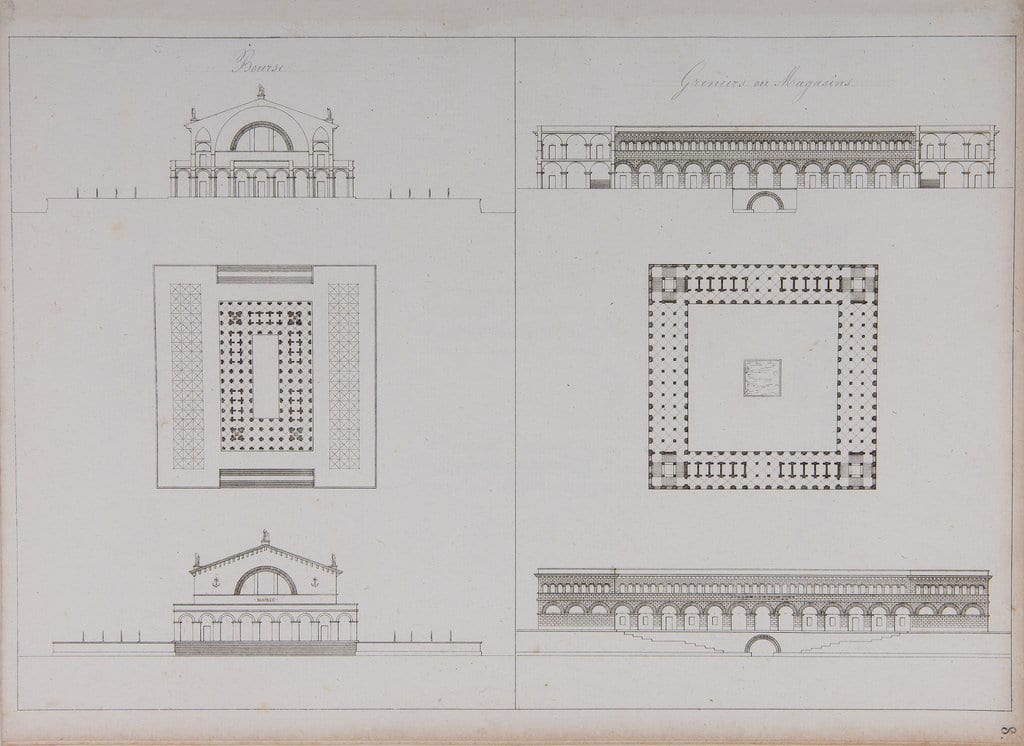

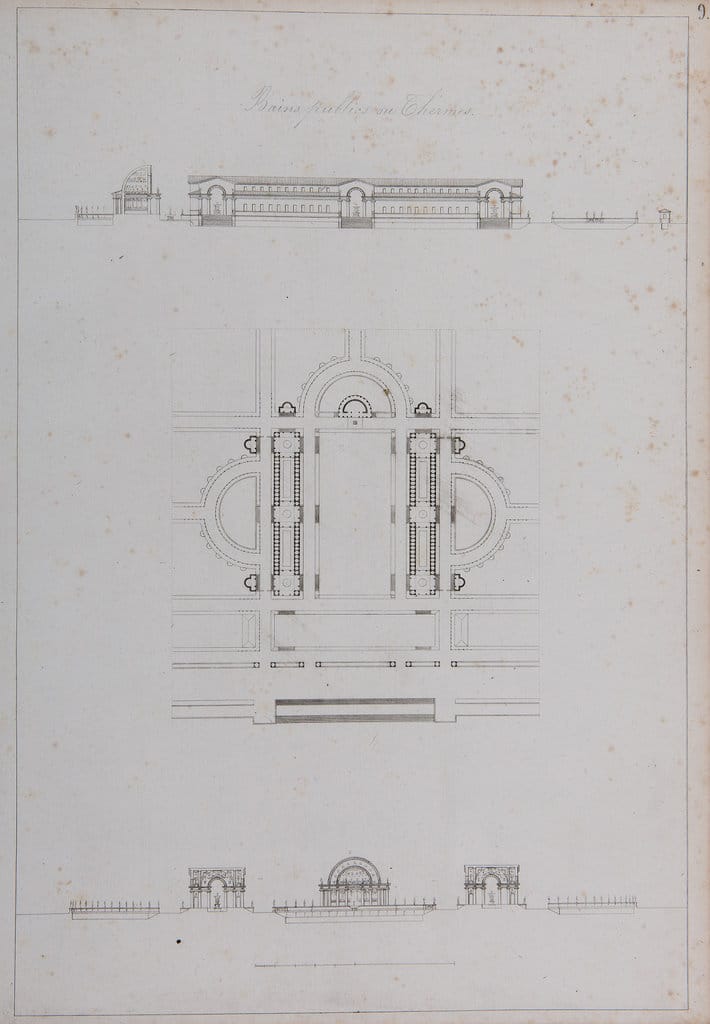

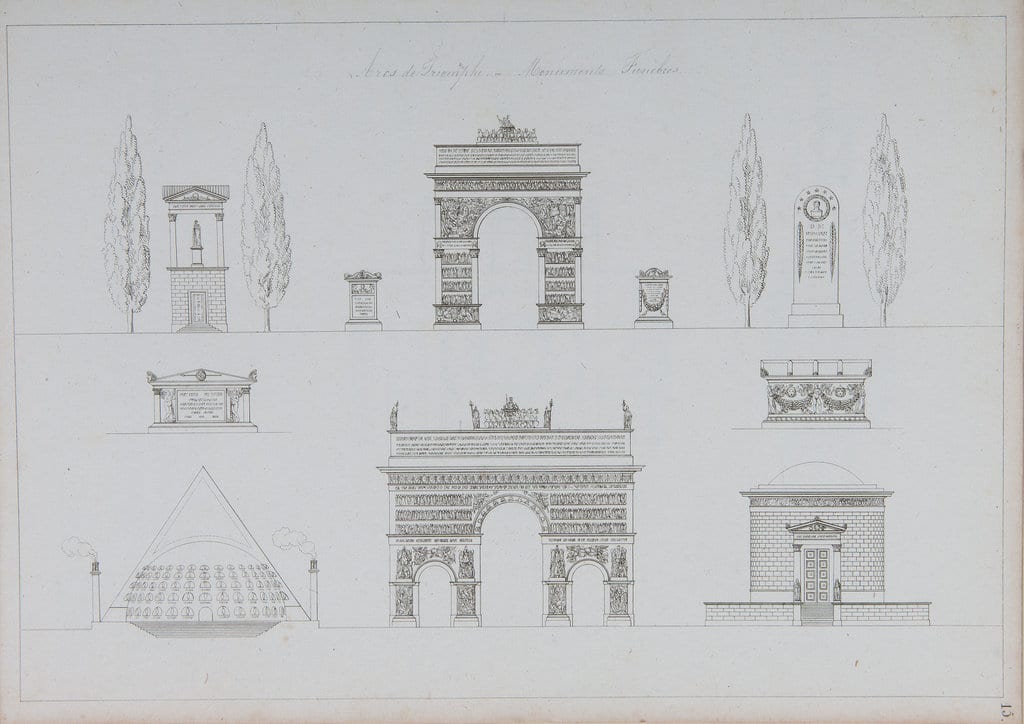

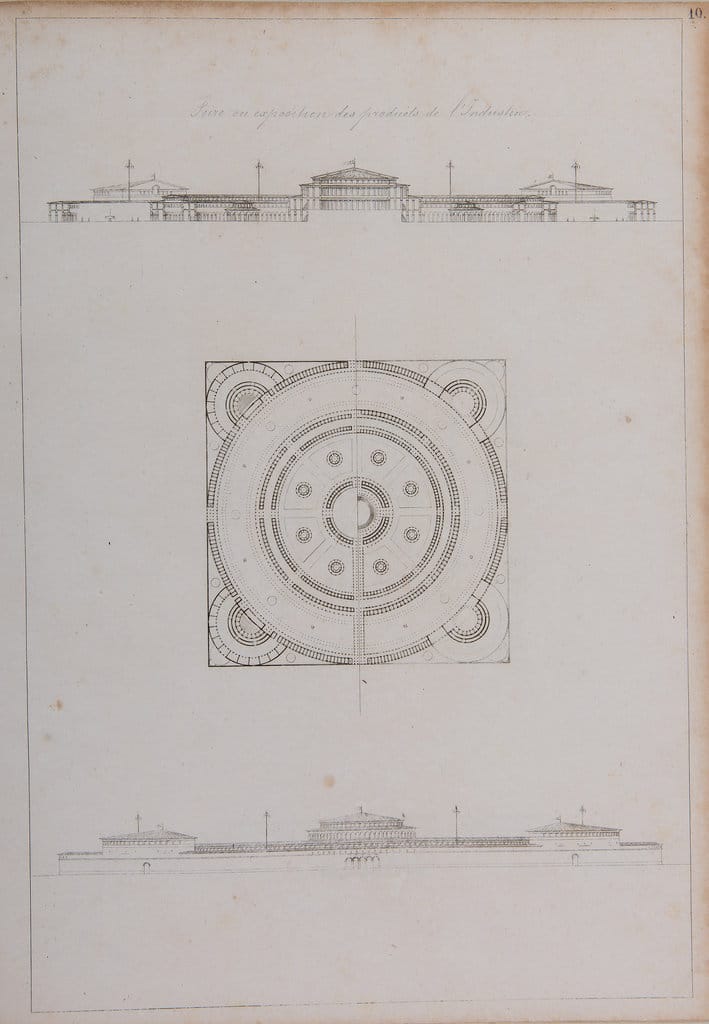

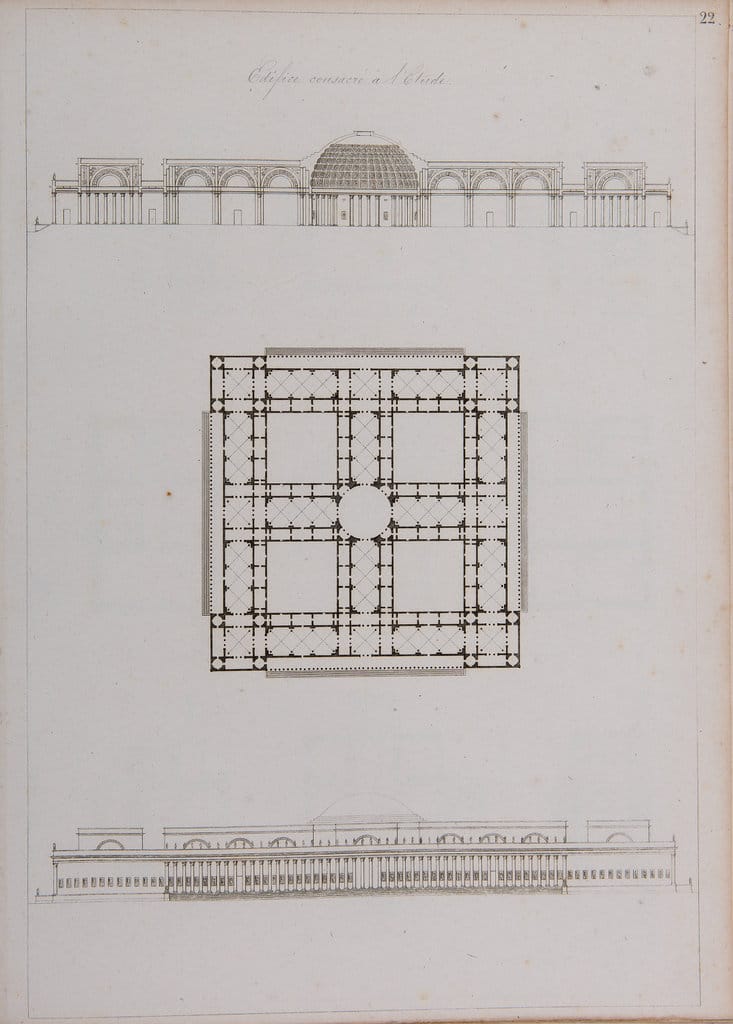

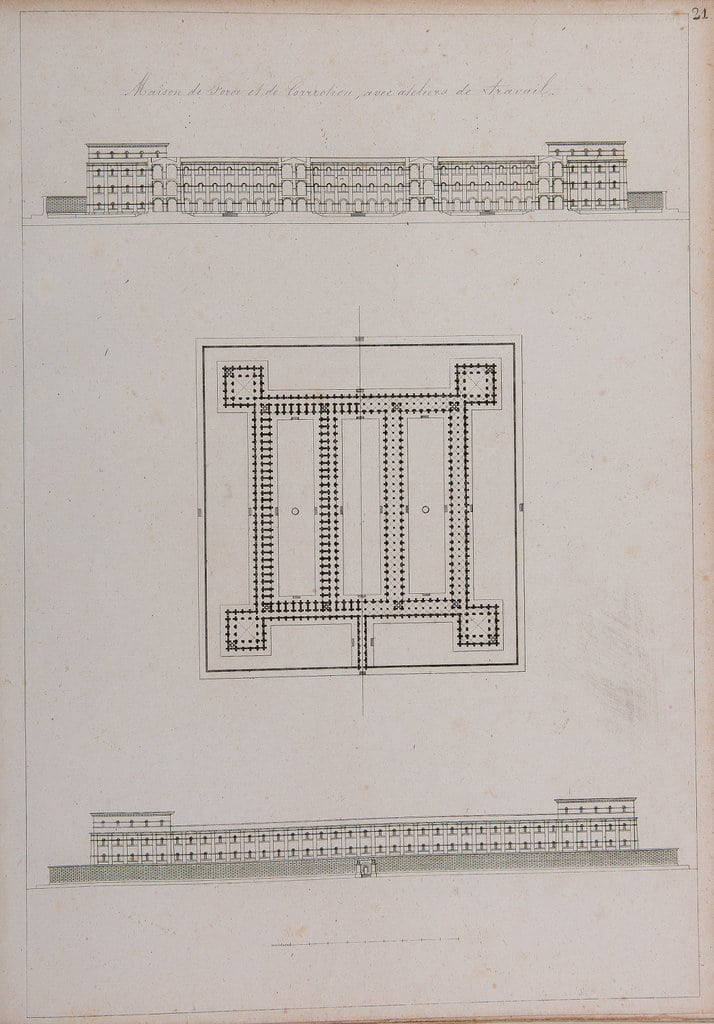

BB: André Châtillon, student of Charles Percier, Prix de Rome in 1809, opened a preparatory atelier for the Ecole des beaux-arts in 1824. These prints are from a large series intended to serve as models for his students. They show the range of new public architectural types that appeared since the end of the eighteenth century, perpetuating the tradition of the generation of Boullée and Ledoux by staying faithful to simple geometric forms and the influence of the antique.

Ratio

Ratio shows how buildings reflect the Enlightenment’s confidence in reason, measure and knowledge, both symbolically (as an imaginary temple to art, knowledge, and reason rises amidst the disorder of the medieval town), ideologically (in the consolidation of artistic and scientific institutes into a single palace of learning) and instrumentally (through such vehicles as the mint or bourse which brought system into the regulation of exchange.)

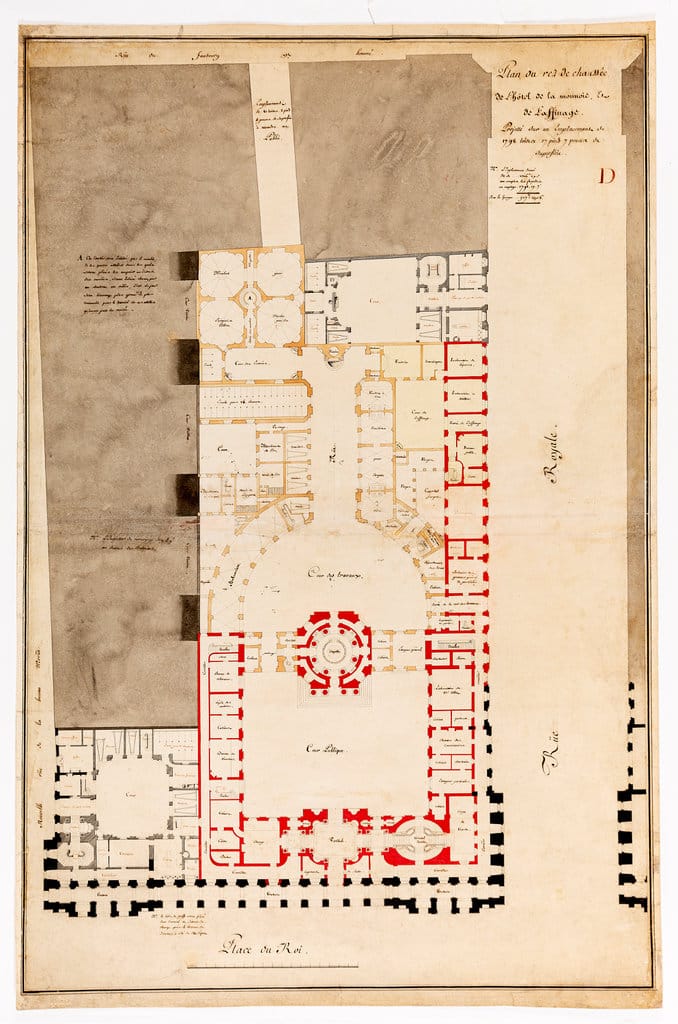

BB: In 1765, the State commissioned Jacques-Denis Antoine, a practically unknown architect who was only twenty-two years old, to design the most important French public building of its time, the Paris Hôtel des Monnaies (the Paris Mint). This plan for an early site shows the way Antoine subtly balanced imperatives of security and efficiency of a factory with the lavishness of a royal administrative building. It embodies the rationality espoused by Enlightenment architects and patrons. The final highly restrained project, constructed above an embankment on the Seine, became a worldwide model of the new approach to public architecture, and was of enormous importance to William Chambers in his designs for Somerset House.

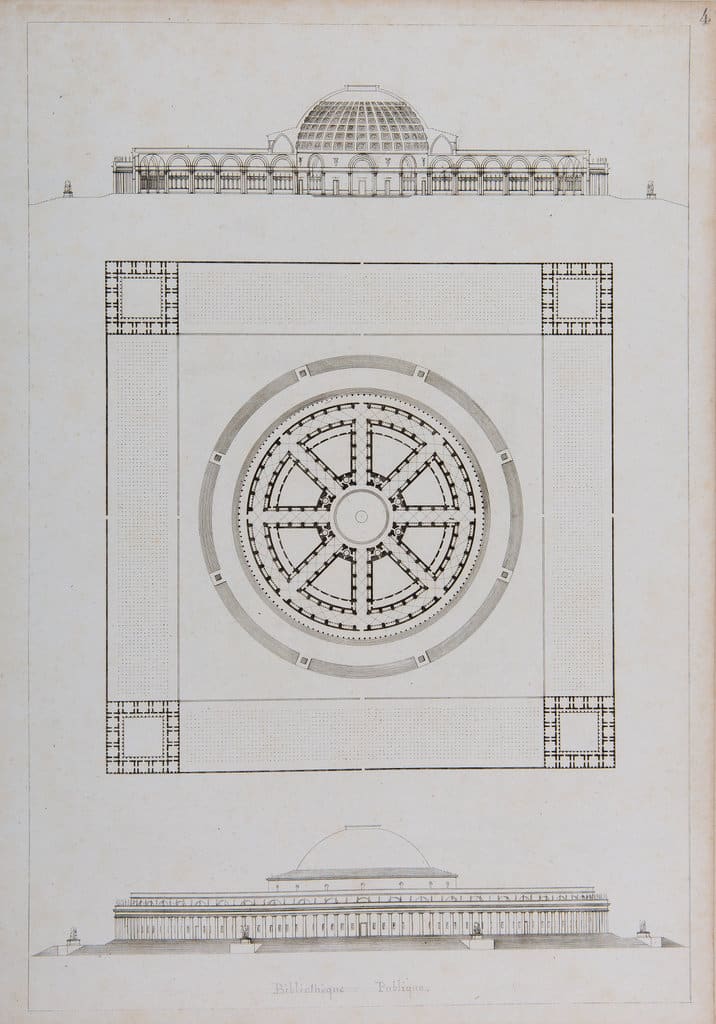

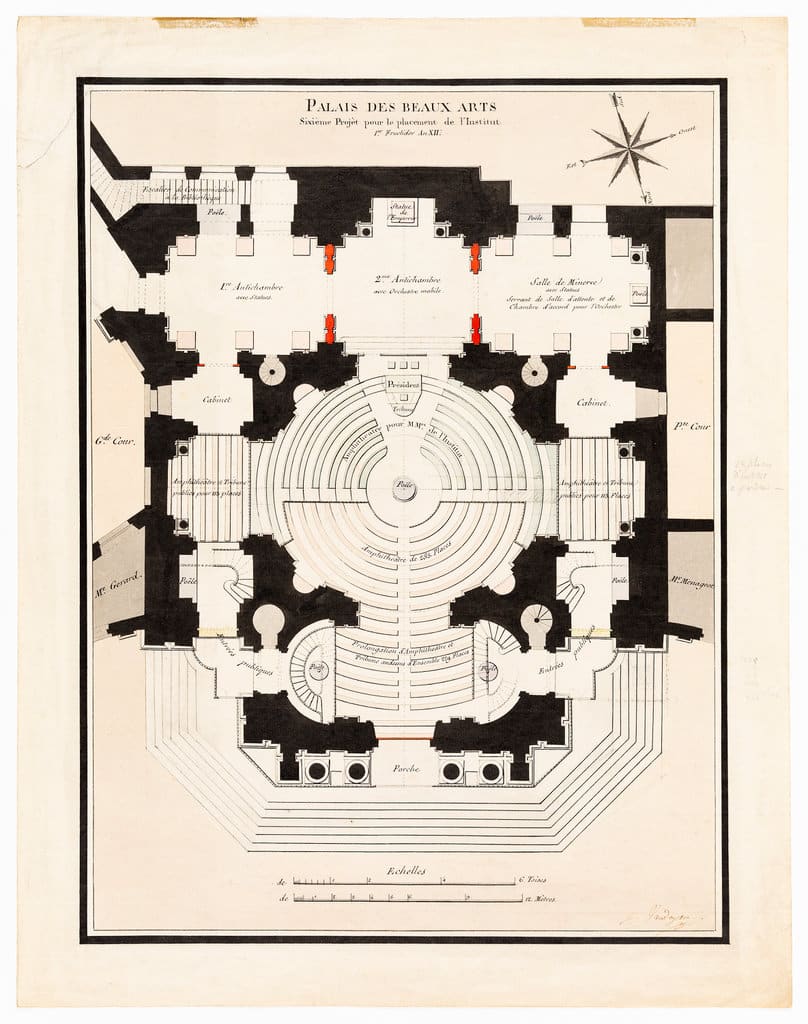

NO: The academies of art, architecture, music, and science were founded in the mid seventeenth century, and consolidated into the Institut de France in 1795. In 1805 Napoleon commissioned Vaudoyer to establish a suite of assembly and meeting rooms, with a library, in the chapel of the former College des Quatre-Nations. This version is one of many proposed as the project evolved. It is striking in its allocation of generous and prominent public galleries, concert chambers, and circulation; in its careful calculation of capacity; and in its highly reasoned, almost scientific approach to delineating a plan and designating its interactions and uses. Based on the circle, signifying the unity of knowledge, the plan envisages a public palace in which advances in science and aesthetics become open to general view.

Lex

Lex suggests the central place of public order, civil regulation, and the rule of law in the construction of a just society, and the determination to represent their fundamental role in asserting the rights and duties of the citizenry, both in the prominence of the buildings to service them and through their iconography.

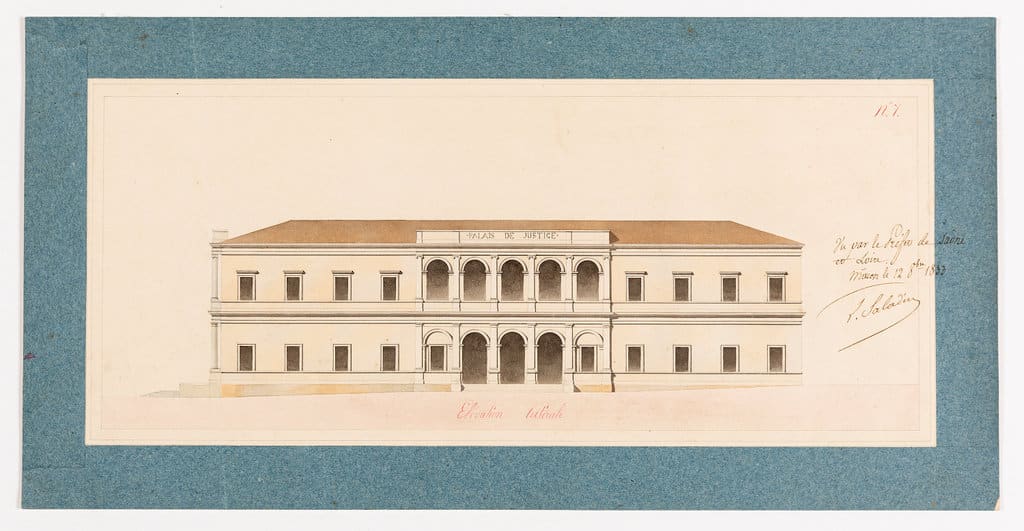

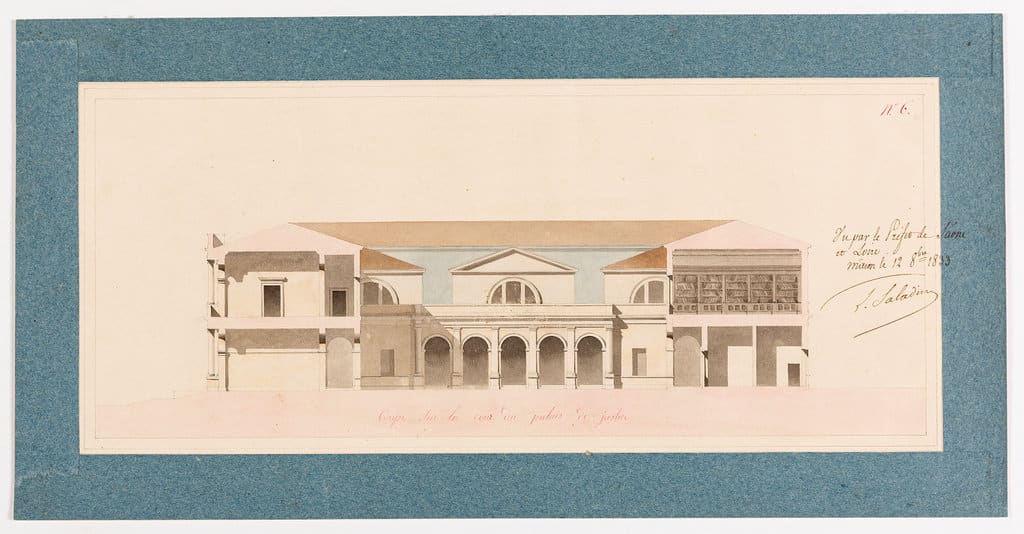

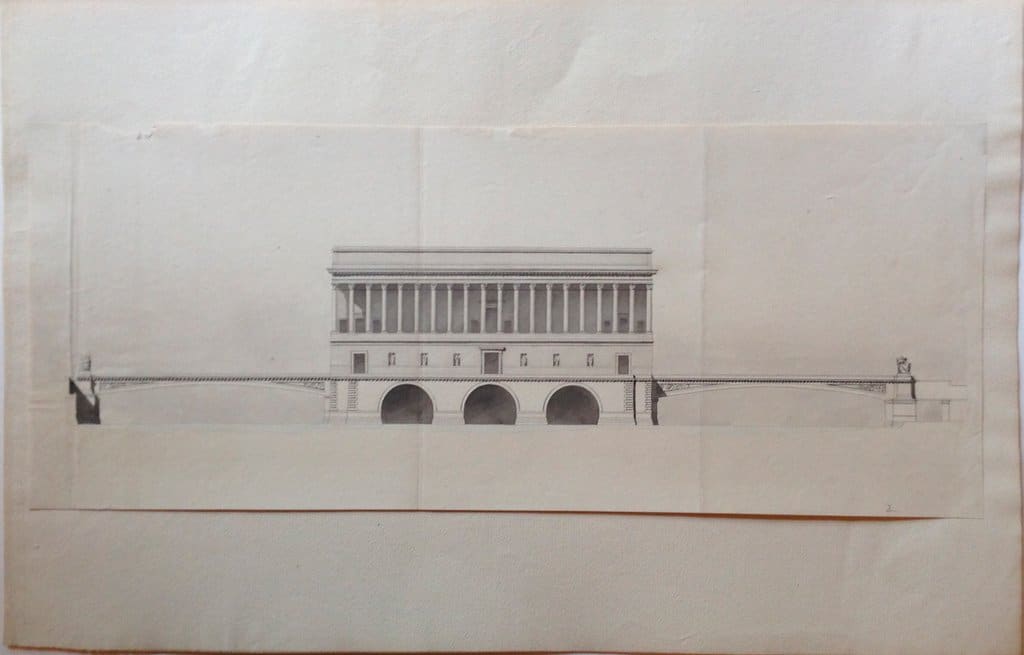

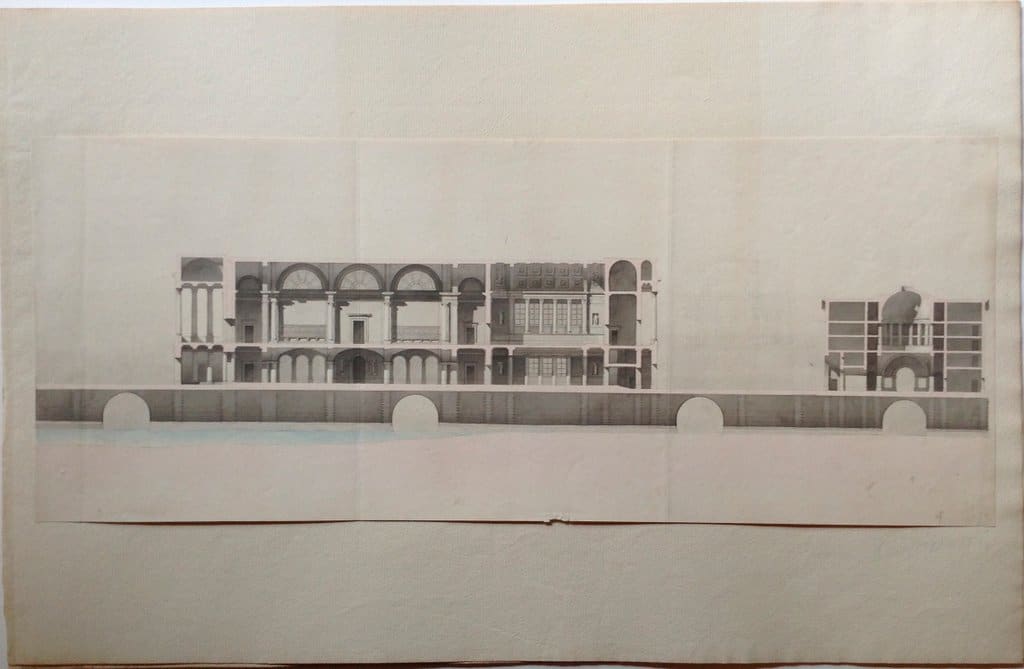

BB: These preparatory drawings by Louis-Pierre Baltard for a pamphlet depicting one of his projects for the palais de justice and prisons in Lyon are perfect examples of the increasing centralization of the architectural world in the post-Revolutionary period. The Parisian Baltard was chosen over local architects and his designs epitomise the restrained classicism defended by the École des Beaux-Arts, where Baltard held the chair of architecture. This scheme, placed high above the rocks in the river Saone at the heart of the city, would have presented the ensemble to traffic on the river and citizenry on the shore as a landmark to the law.

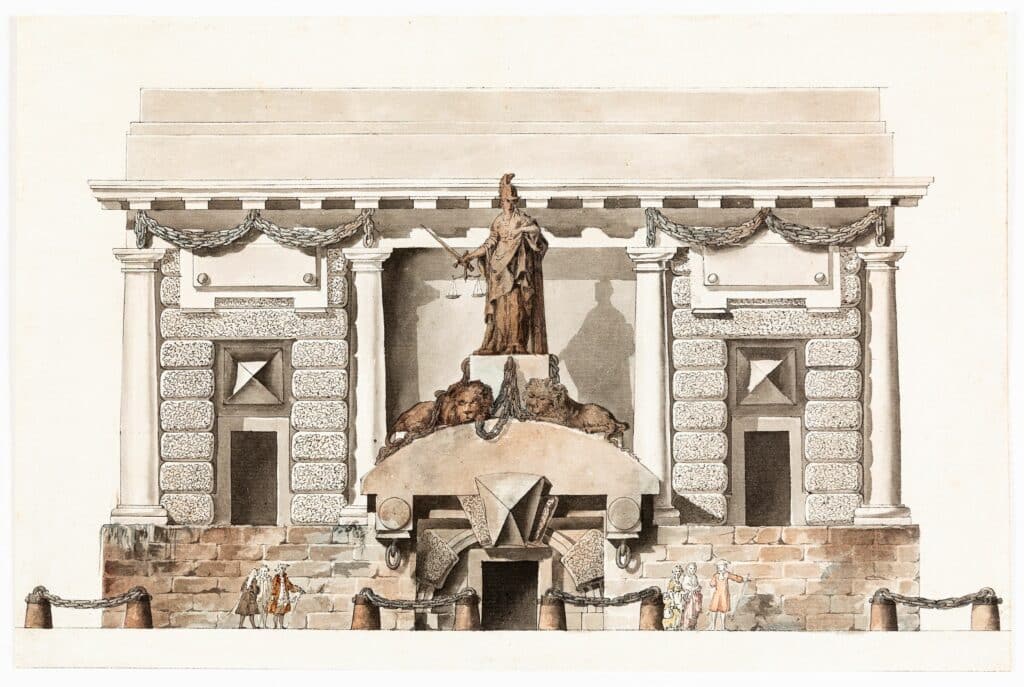

NO: From a series of drawings and engravings proposing varied iconographic and architectural elements for a standardised form of local guardhouse or prison that would symbolise (here with slightly whimsical ferocity) the impartiality of justice and the authority of the police. By illustrating the escort of a thief into the gates from a neighbouring market stall and the comfortable demeanour of passers-by, Delafosse draws attention to the civilising force of the law in protecting the commerce, civility and sociability of the city street.

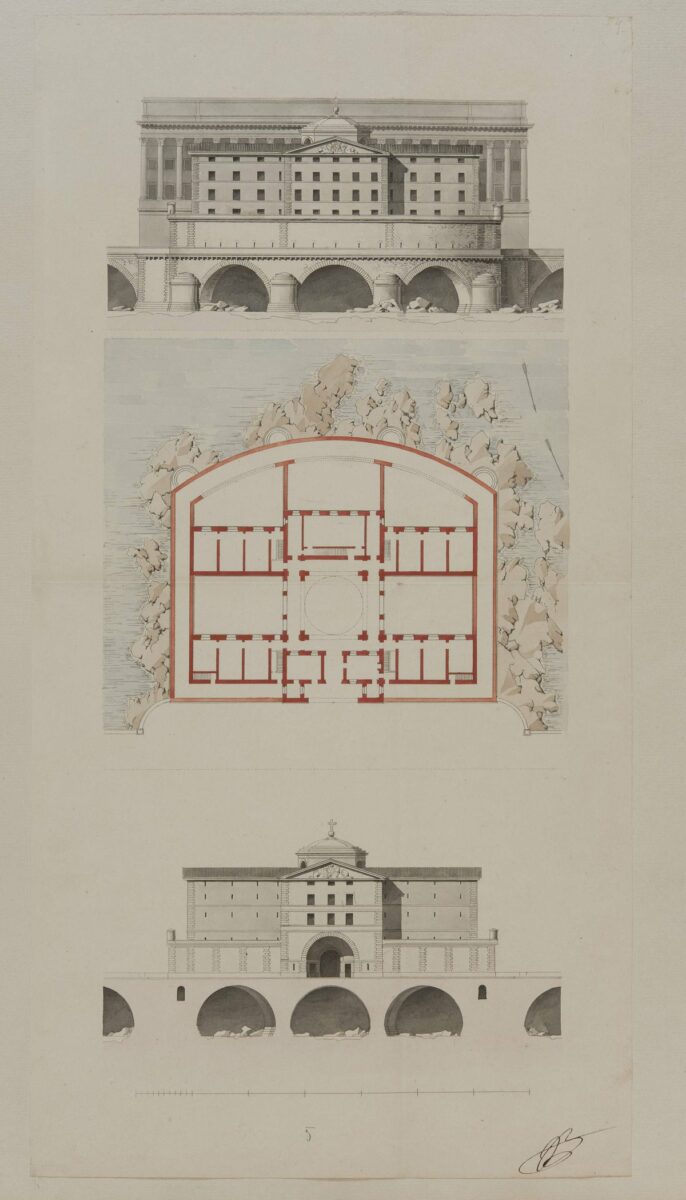

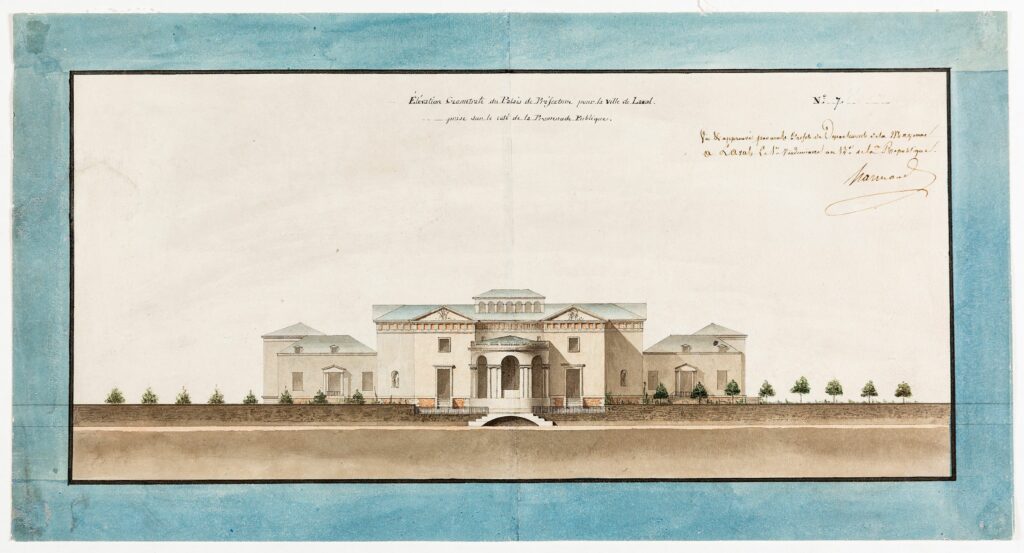

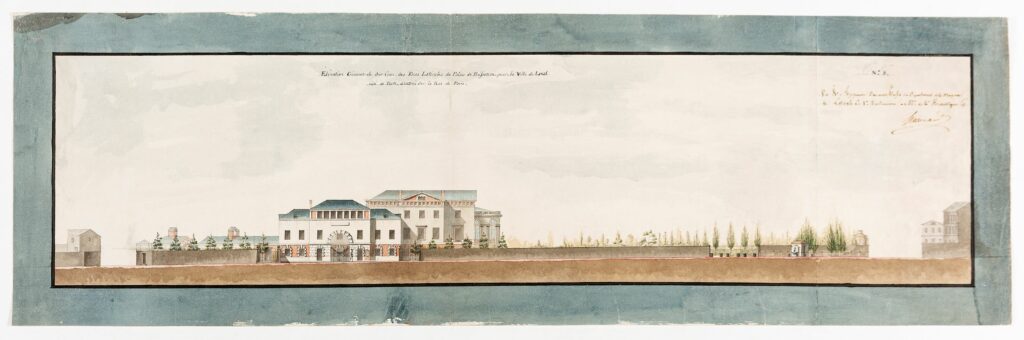

NO: The Dominican monastery in the centre of the city of Laval on the Loire was seized during the first year of the Revolution, while an expansion was in construction, and then acquired by the regional government as its seat of administration. In 1803 the medieval cloister and chapel were demolished and these designs for a completely new and more efficient building were made, asserting the presence of the central government in the provincial capital, yet appearing as something of a people’s palace, marked by a public promenade and gardens. Only the service quarters and entry in Bricard’s Palladian design were built, and the palais’s later architects reverted, under the Restoration, to the more closed and ecclesiastical plan the monks had begun to build before the Revolution.

Spectaculum

Spectaculum is concerned with the embellishment of the city as a place of pleasure, not just in the increase in the scale and range of its sites of social intercourse, but, in its newly ordered grace, as a spectacle and an architectural landscape of delight in its own right.

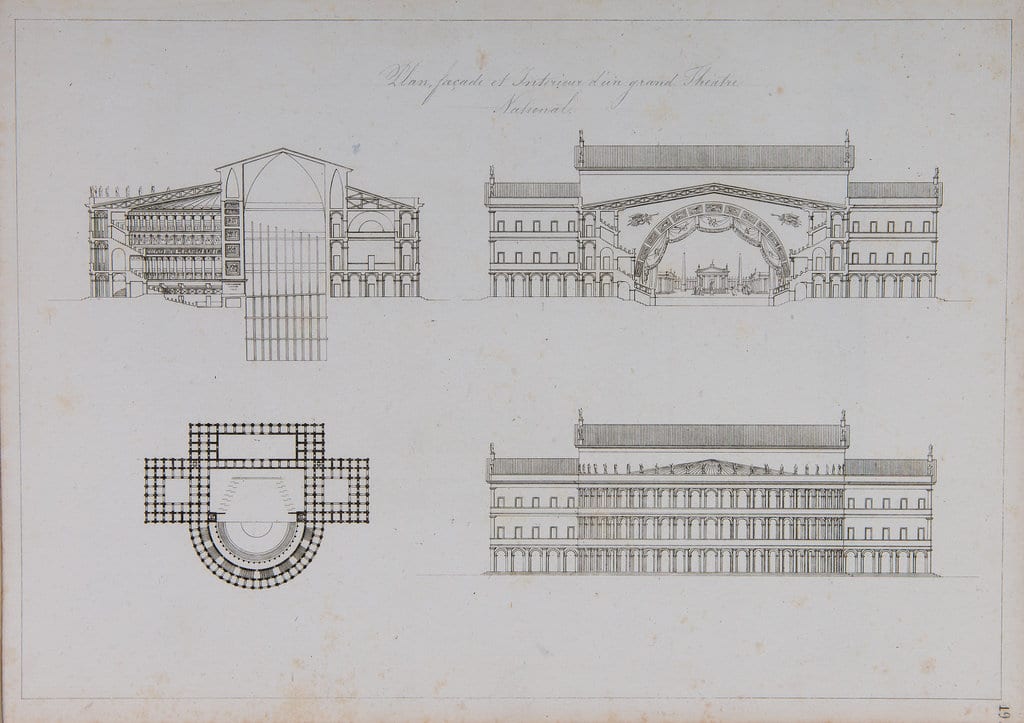

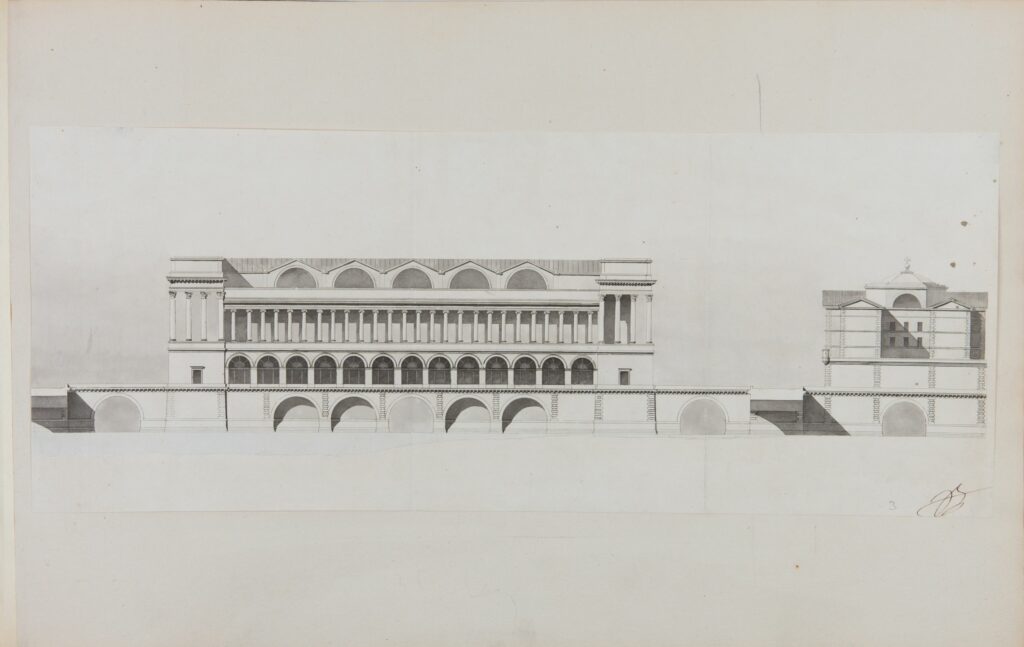

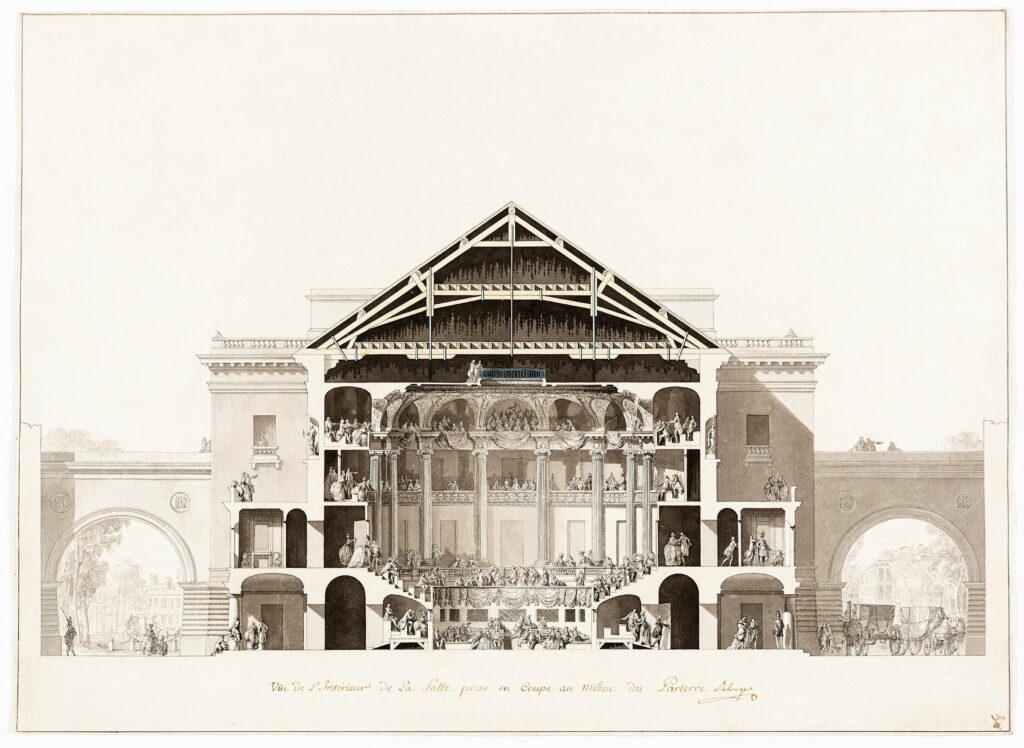

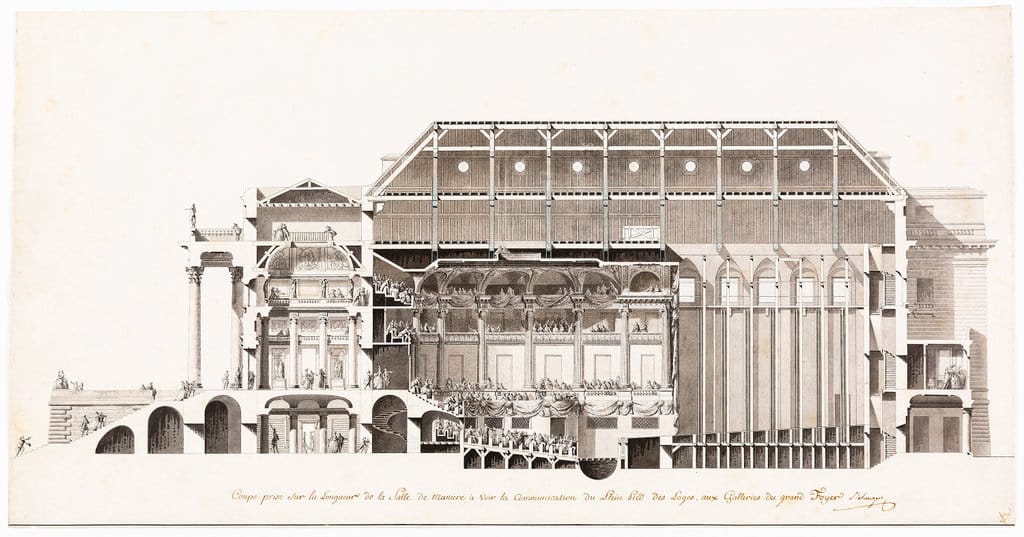

BB: In these magnificent drawings for a theatre to be built in Paris for the troupe of the Comédiens-Italiens, François-Joseph Bélanger, architect of the brother of the king, tried to design new solutions in terms of comfort for the spectators and easy circulation at a moment when fire hazards were numerous. Because the theatre’s architect had already been chosen, this drawing was intended to serve as publicity for Bélanger, who until then had received only private commissions.

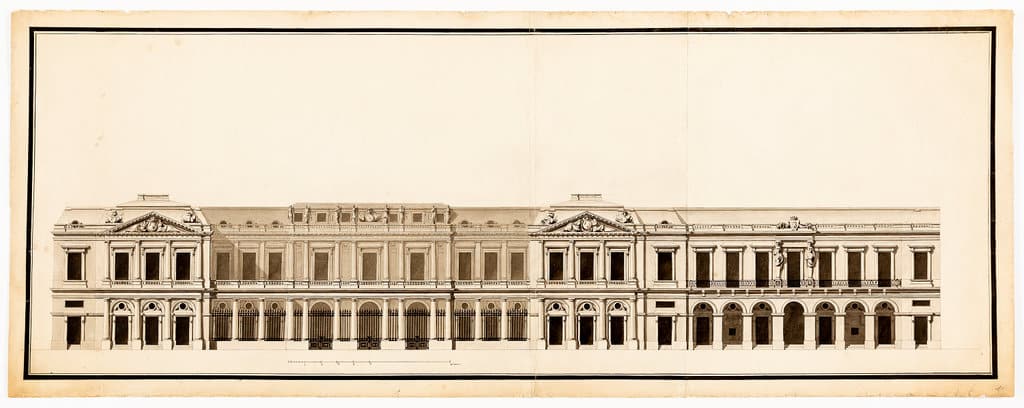

In 1764, Moreau, official architect of the city, was put in charge of rebuilding the Palais Royal opera, conceded to the Paris municipality by its owner, the duke d’Orléans. He took the opportunity to give the princely palace a new street façade with a larger public presence and largely inspired by the baroque Roman examples he admired while at the French Academy between 1754 and 1756. Here, embellishment derives from the repetition of motifs aptly interrupted by monumental sculptures.

NO: In this student project, Seheult proposes a théâtre de verdure, or open-air theatre, in which the enjoyment of what unfolds behind the stage – the blending of a huge monumental cascade and peristyle with a Rousseauian Romantic landscape – is as important as the music or masque performed upon it.

Sanitas

Sanitas, or the notion of civic hygiene, looks at the regulation of commerce for the benefit of public health and convenience, taking the particular example of processing and trading in perishable goods through raised, well-aired, watered, and open markets.

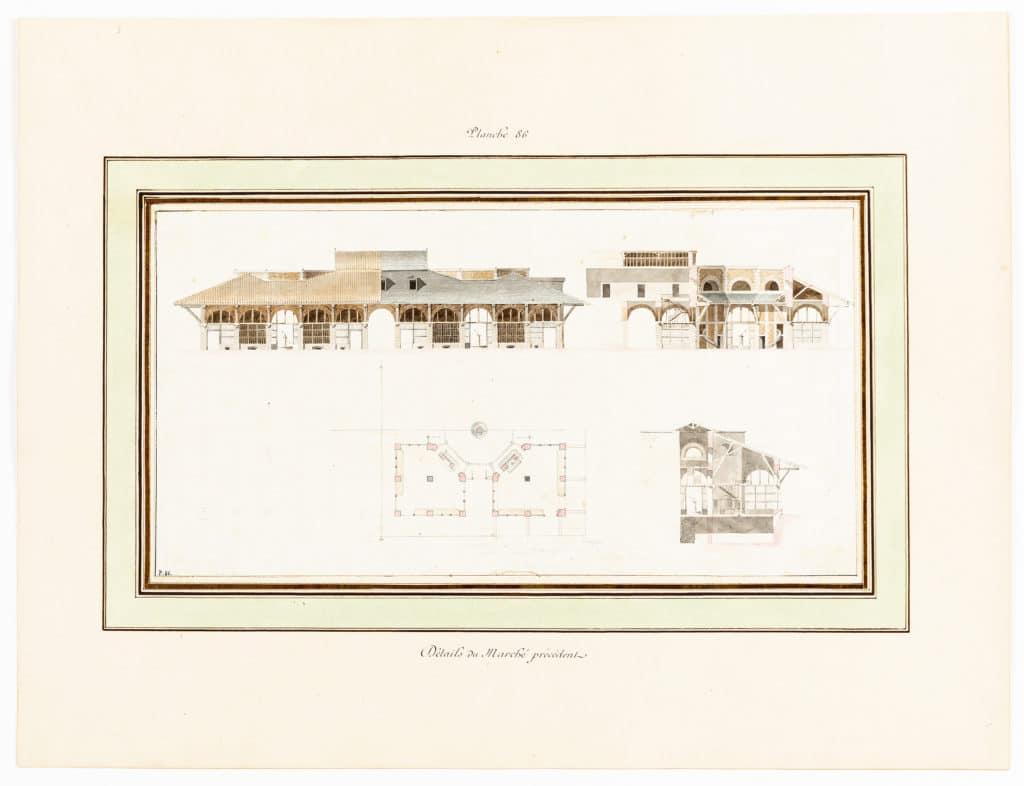

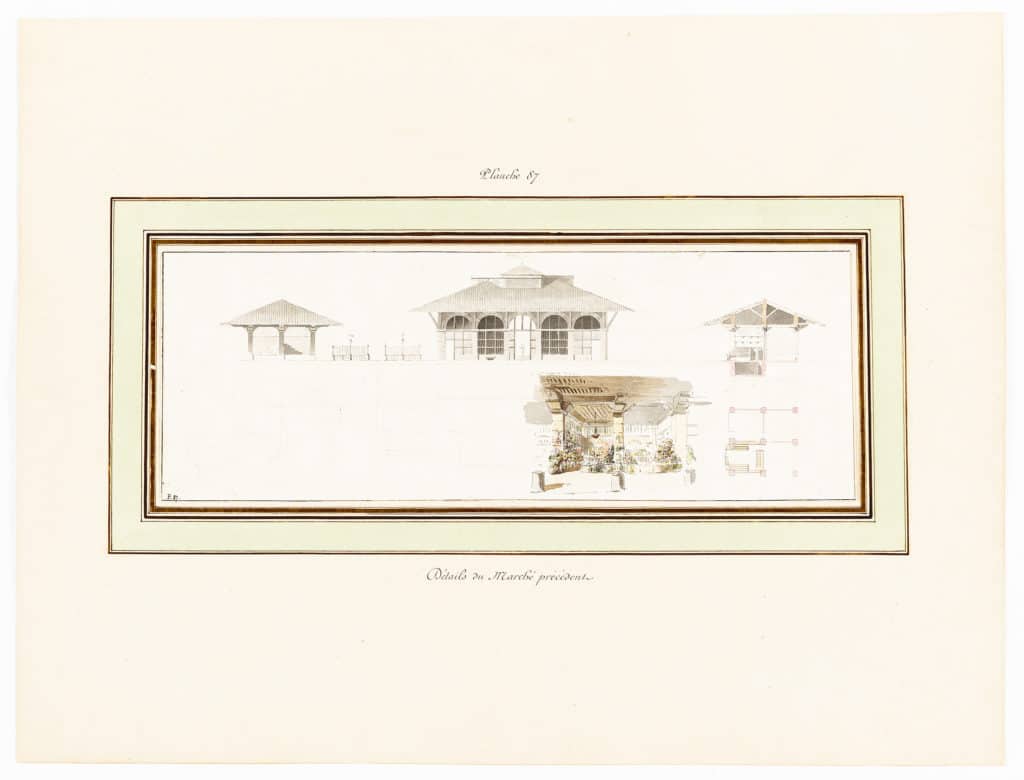

BB: Pierre-François-Léonard Fontaine intended to include these drawings in an unrealised publication of public architecture models. Markets became a crucial architectural type symbolic of hygienic and commercial progress promoted by public authorities in the nineteenth century. Fontaine addresses these concerns in deliberately vernacular, informal and unimposing structures, producing a strikingly practical compromise for a court architect.

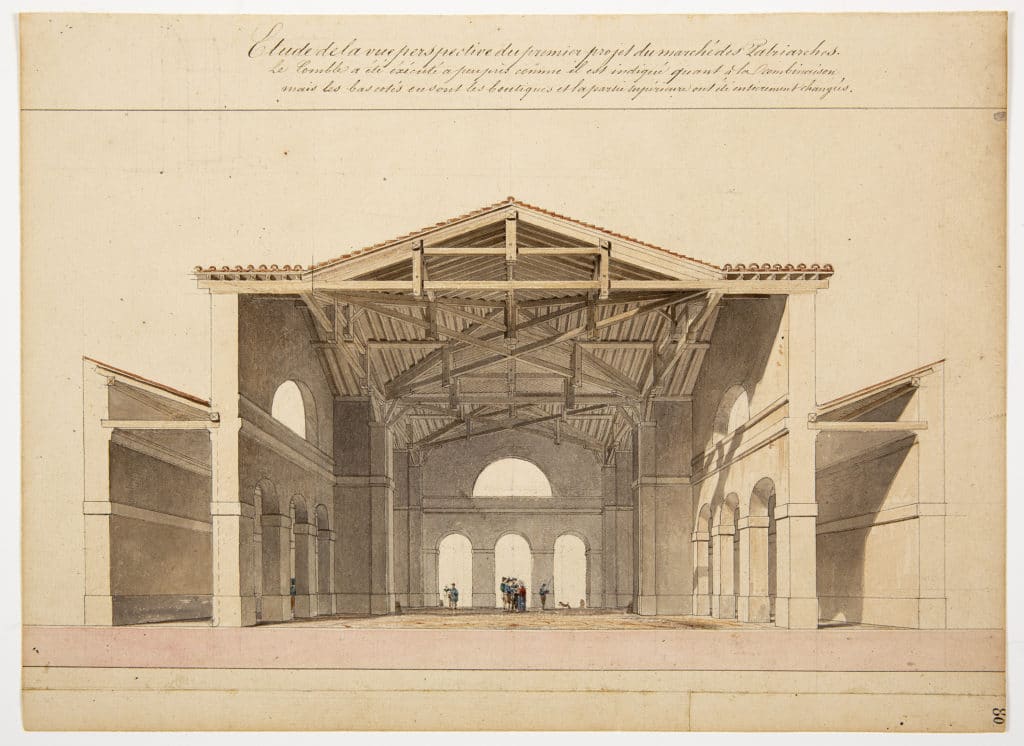

NO: Chatillon’s spacious covered market, originally designed as a sanitary site for the sale of fresh foods, was constructed near the rue Mouffetard on the left bank of Paris between 1828 and 1832. As the city grew it became a flea market and a favourite subject of photographers, writers and film-makers depicting the crowded but increasingly insalubrious character of the city’s working class quarters. It was demolished in 1953. The inscription – added to this study when gathered into an album of Chatillon’s work – notes that the core of the project followed this first design, with its raised platform and high ventilating roof to cleanse the air, but that both the side aisles for little shops and the configuration of the upper roof were “extremely changed.”

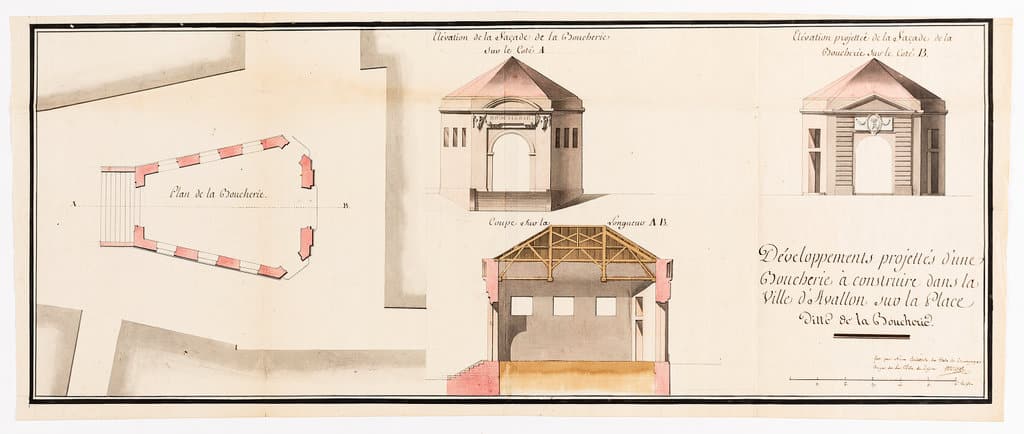

NO: The small city of Avallon was the centre of an extensive trade in cattle, sheep, leather and meats. This proposal by the senior official architect of Burgundy envisages a well-aired, raised hygienic market for more than twenty of the city’s butchers, who had ceded their corporation and its original market (in a roughly converted and unsanitary town house) to the city in 1757. Le Jolivet’s distinctive landmark would have filled the triangular place near where the routes to Paris and Lyon met at the centre of the town. The project as drawn was apparently not constructed; but a city boucherie based on its principles appeared in 1792 and became noted for the cleanliness and condition of its meats through the use of the “current of air” produced by a high roof, many openings, and a position elevated above the dust and detritus of the street.

Exemplum

Exemplum shows the dissemination of this civic language and its aspirations as they moved from the academy to the ground, and from regional capitals to the provincial town, in a selection of public building projects developed in the early 1830s by a recent graduate of the Ecole des Beaux Arts for the small Burgundian city of Macon.

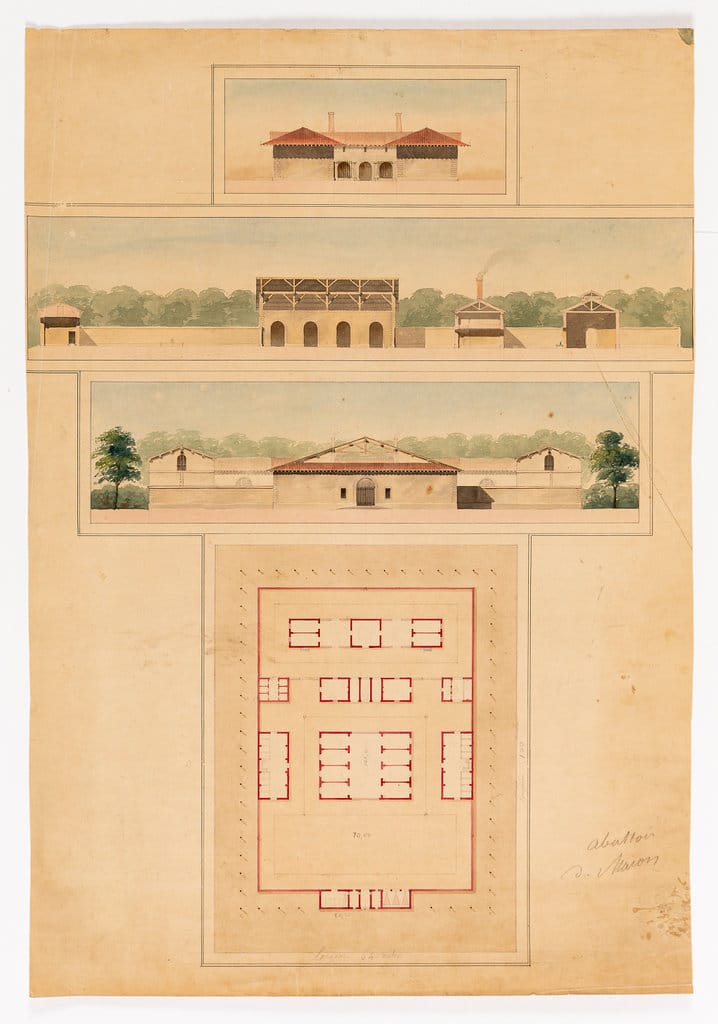

BB: Born in the small Burgundian town of Mâcon and trained in Paris, Paul Piot returned to his native city to design most of its public buildings in accord with tenets of the Ecole des beaux-arts. Abattoirs (slaughterhouses) were key programmes for local authorities seeking to demonstrate their public concern for hygiene and food supply, often consolidating these messy and unhealthy processes at sites on the perimeter of the city. Here, Piot artfully separates the different animal species and spaces according to function: holding stations, slaughtering room, processing factory and administration.