Arrows

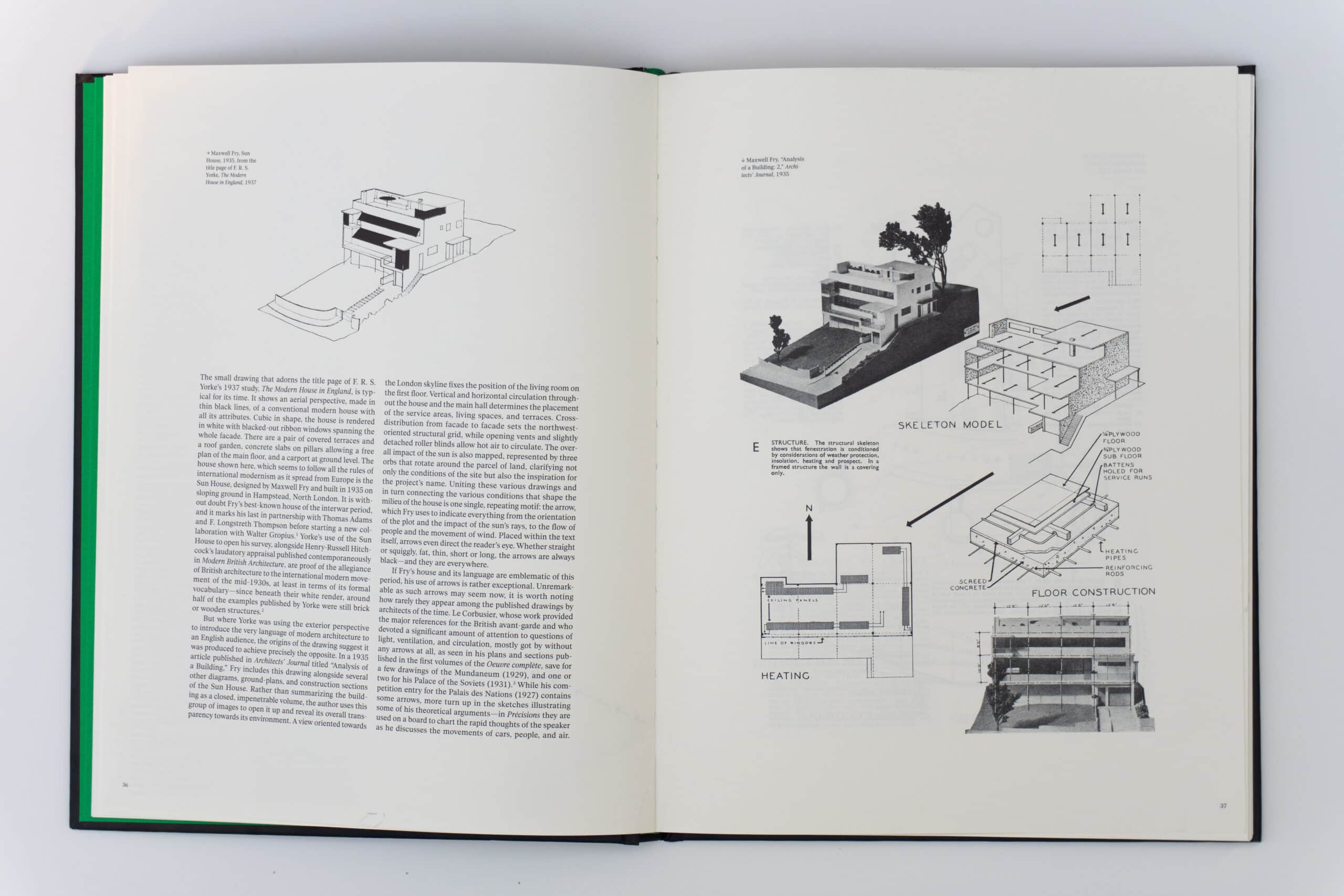

The small drawing that adorns the title page of F. R. S. Yorke’s 1937 study, The Modern House in England, is typical for its time. It shows an aerial perspective, made in thin black lines, of a conventional modern house with all its attributes. Cubic in shape, the house is rendered in white with blacked-out ribbon windows spanning the whole facade. There are a pair of covered terraces and a roof garden, concrete slabs on pillars allowing a free plan of the main floor, and a carport at ground level. The house shown here, which seems to follow all the rules of international modernism as it spread from Europe is the Sun House, designed by Maxwell Fry and built in 1935 on sloping ground in Hampstead, North London. It is without doubt Fry’s best-known house of the interwar period, and it marks his last in partnership with Thomas Adams and F. Longstreth Thompson before starting a new collaboration with Walter Gropius.[1] Yorke’s use of the Sun House to open his survey, alongside Henry-Russell Hitchcock’s laudatory appraisal published contemporaneously in Modern British Architecture, are proof of the allegiance of British architecture to the international modern movement of the mid-1930s, at least in terms of its formal vocabulary-since beneath their white render, around half of the examples published by Yorke were still brick or wooden structures.[2]

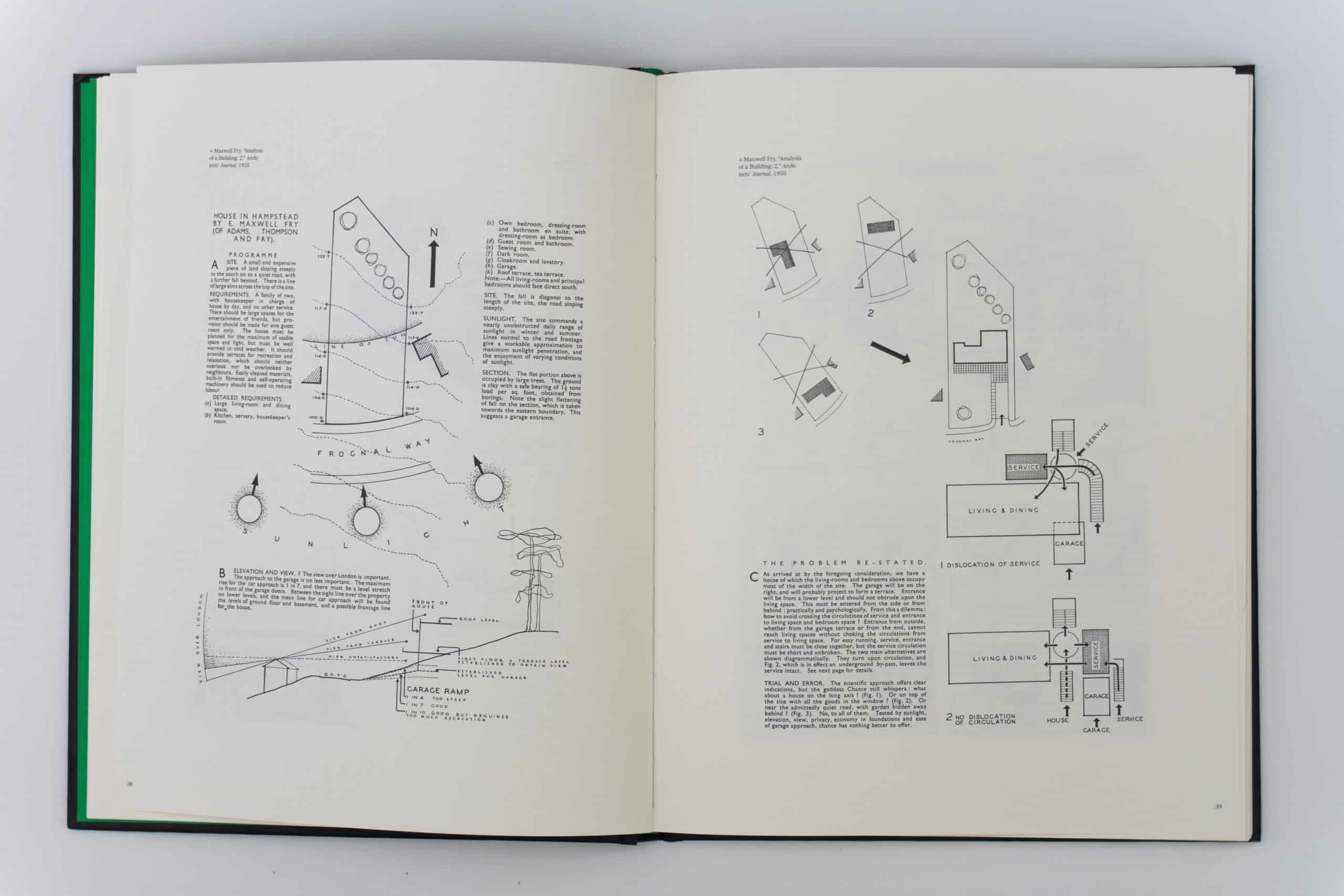

But where Yorke was using the exterior perspective to introduce the very language of modern architecture to an English audience, the origins of the drawing suggest it was produced to achieve precisely the opposite. In a 1935 article published in Architects’ Journal titled ‘Analysis of a Building,’ Fry includes this drawing alongside several other diagrams, ground-plans, and construction sections of the Sun House. Rather than summarising the building as a closed, impenetrable volume, the author uses this group of images to open it up and reveal its overall transparency towards its environment. A view oriented towards the London skyline fixes the position of the living room on the first floor. Vertical and horizontal circulation throughout the house and the main hall determines the placement of the service areas, living spaces, and terraces. Cross distribution from facade to facade sets the north-west oriented structural grid, while opening vents and slightly detached roller blinds allow hot air to circulate. The overall impact of the sun is also mapped, represented by three orbs that rotate around the parcel of land, clarifying not only the conditions of the site but also the inspiration for the project’s name. Uniting these various drawings and in turn connecting the various conditions that shape the milieu of the house is one single, repeating motif: the arrow, which Fry uses to indicate everything from the orientation of the plot and the impact of the sun’s rays, to the flow of people and the movement of wind. Placed within the text itself, arrows even direct the reader’s eye. Whether straight or squiggly, fat, thin, short or long, the arrows are always black—and they are everywhere.

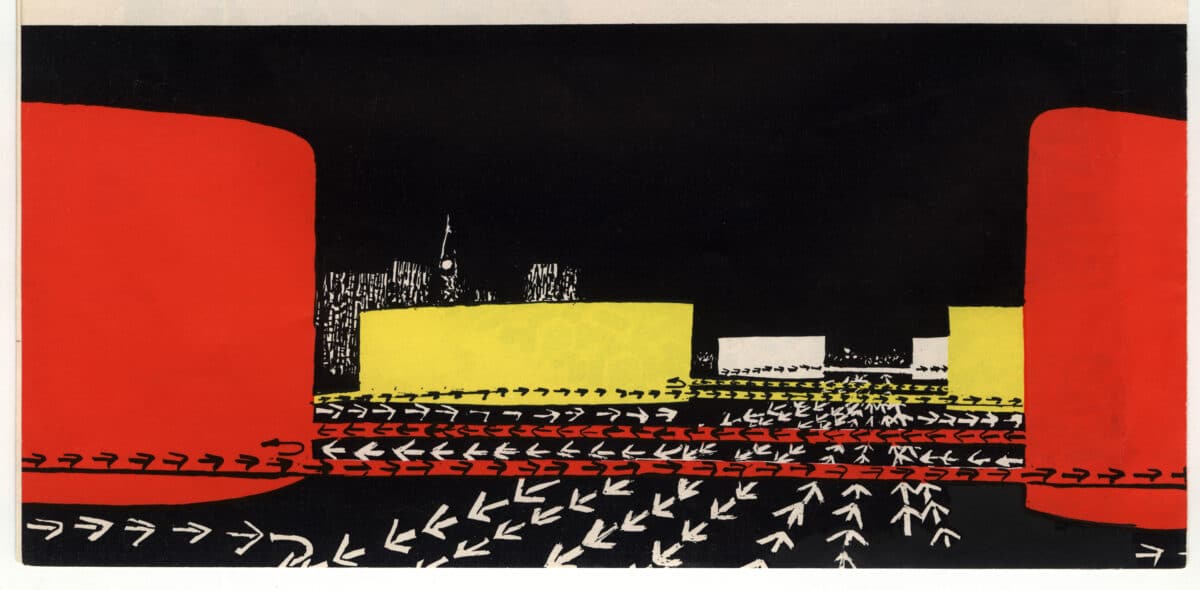

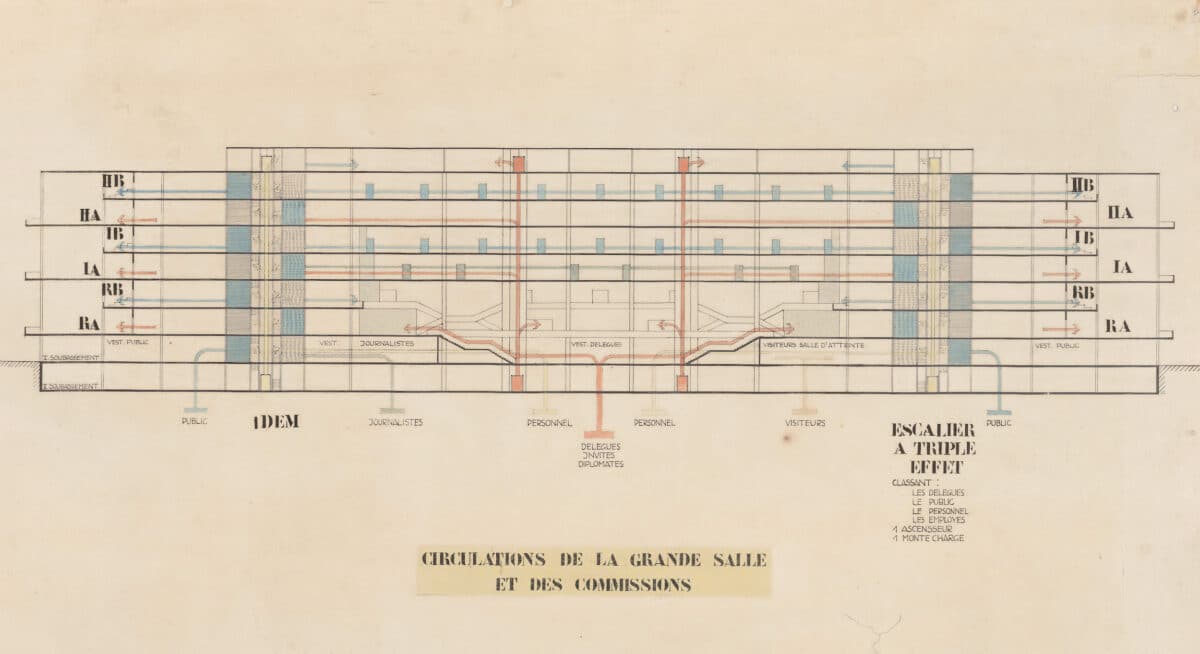

If Fry’s house and its language are emblematic of this period, his use of arrows is rather exceptional. Unremarkable as such arrows may seem now, it is worth noting how rarely they appear among the published drawings by architects of the time. Le Corbusier, whose work provided the major references for the British avant-garde and who devoted a significant amount of attention to questions of light, ventilation, and circulation, mostly got by without any arrows at all, as seen in his plans and sections published in the first volumes of the Oeuvre complète, save for a few drawings of the Mundaneum (1929), and one or two for his Palace of the Soviets (1931).[3] While his competition entry for the Palais des Nations (1927) contains some arrows, more turn up in the sketches illustrating some of his theoretical arguments—in Précisions they are used on a board to chart the rapid thoughts of the speaker as he discusses the movements of cars, people, and air.

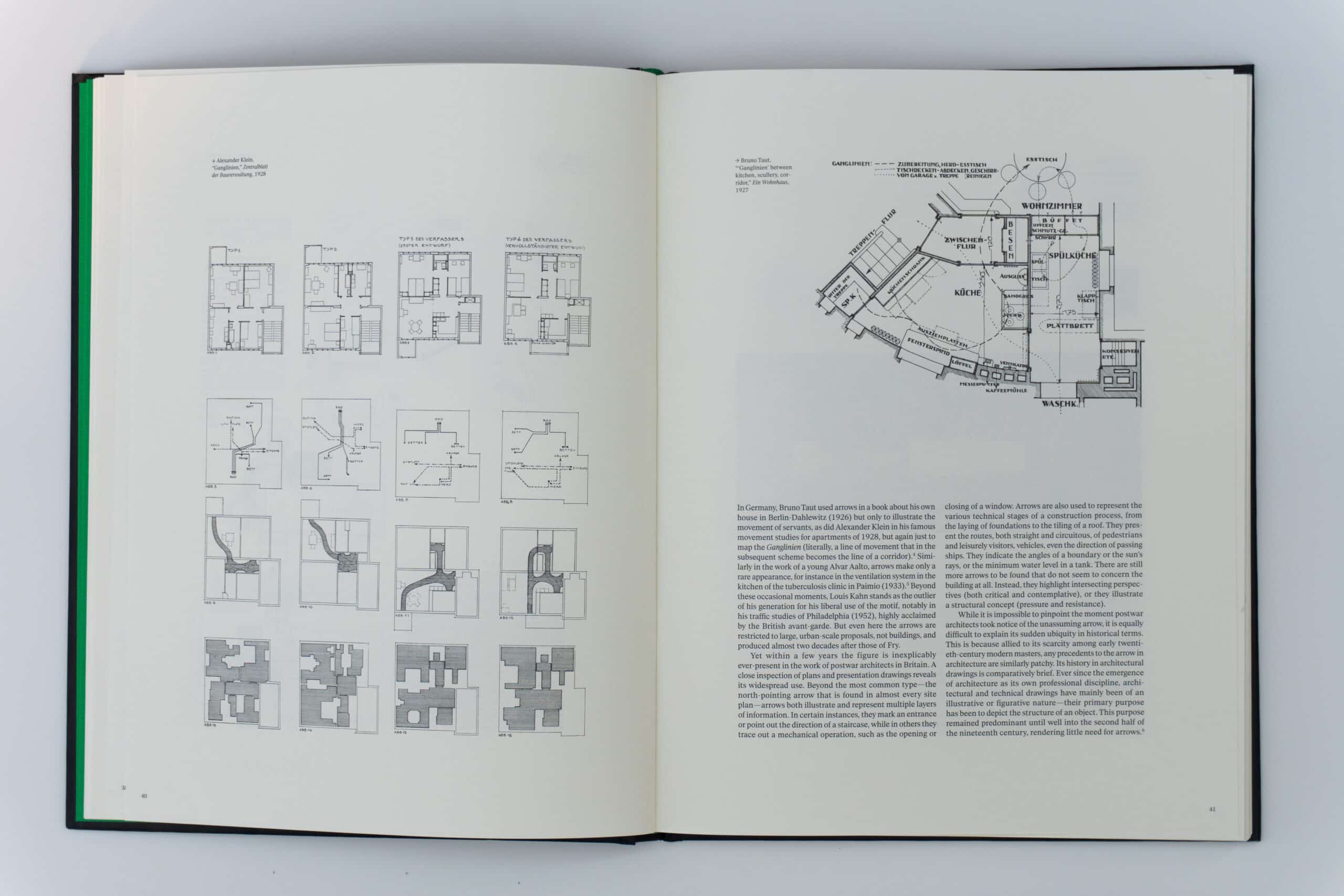

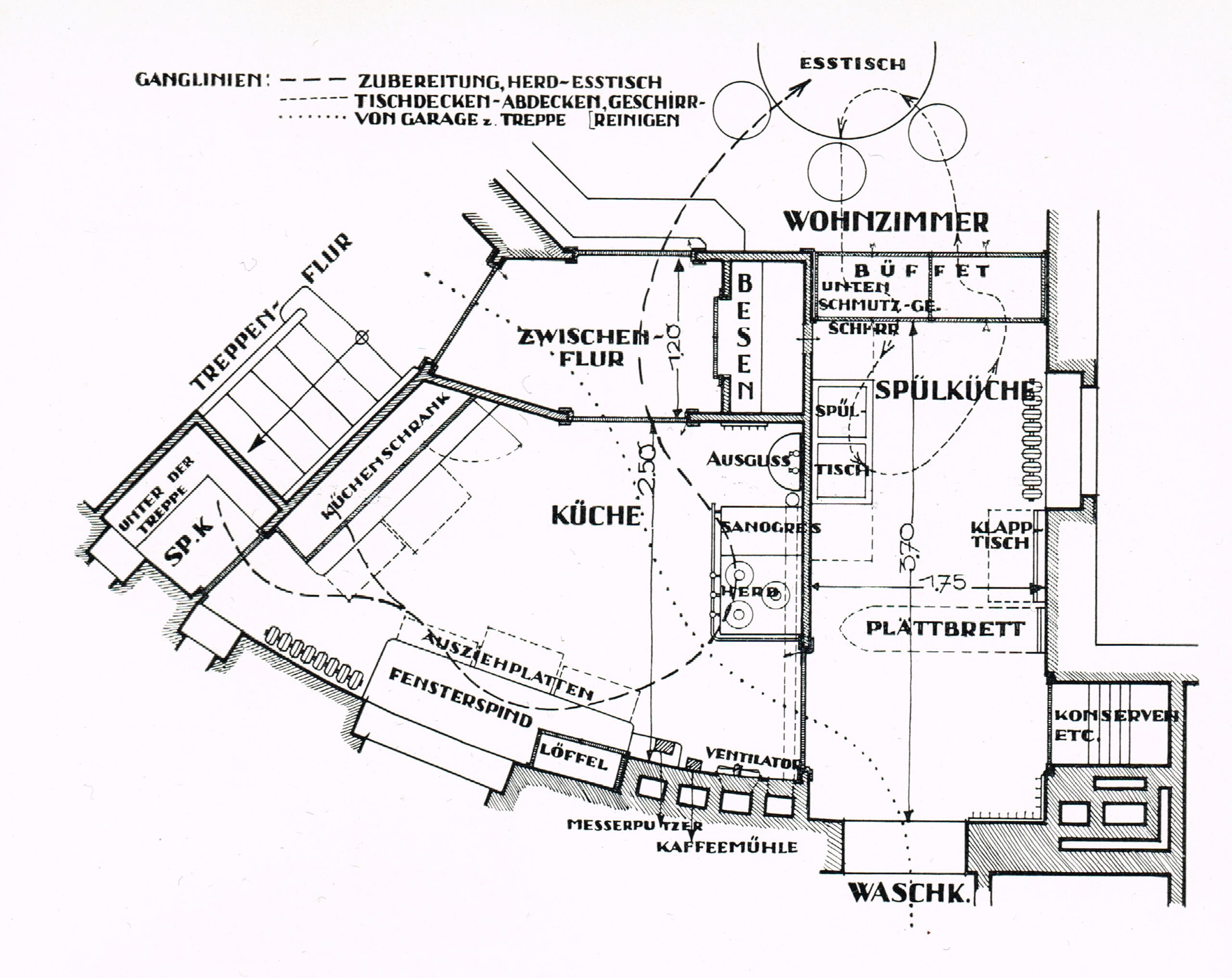

In Germany, Bruno Taut used arrows in a book about his own house in Berlin-Dahlewitz (1926) but only to illustrate the movement of servants, as did Alexander Klein in his famous movement studies for apartments of 1928, but again just to map the Ganglinien (literally, a line of movement that in the subsequent scheme becomes the line of a corridor).[4] Similarly in the work of a young Alvar Aalto, arrows make only a rare appearance, for instance in the ventilation system in the kitchen of the tuberculosis clinic in Paimio (1933).[5] Beyond these occasional moments, Louis Kahn stands as the outlier of his generation for his liberal use of the motif, notably in his traffic studies of Philadelphia (1952), highly acclaimed by the British avant-garde. But even here the arrows are restricted to large, urban-scale proposals, not buildings, and produced almost two decades after those of Fry.

Yet within a few years the figure is inexplicably ever-present in the work of postwar architects in Britain. A close inspection of plans and presentation drawings reveals its widespread use. Beyond the most common type—the north-pointing arrow that is found in almost every site plan-arrows both illustrate and represent multiple layers of information. In certain instances, they mark an entrance or point out the direction of a staircase, while in others they trace out a mechanical operation, such as the opening or closing of a window. Arrows are also used to represent the various technical stages of a construction process, from the laying of foundations to the tiling of a roof. They present the routes, both straight and circuitous, of pedestrians and leisurely visitors, vehicles, even the direction of passing ships. They indicate the angles of a boundary or the sun’s rays, or the minimum water level in a tank. There are still more arrows to be found that do not seem to concern the building at all. Instead, they highlight intersecting perspectives (both critical and contemplative), or they illustrate a structural concept (pressure and resistance).

While it is impossible to pinpoint the moment postwar architects took notice of the unassuming arrow, it is equally difficult to explain its sudden ubiquity in historical terms. This is because allied to its scarcity among early twentieth-century modern masters, any precedents to the arrow in architecture are similarly patchy. Its history in architectural drawings is comparatively brief. Ever since the emergence of architecture as its own professional discipline, architectural and technical drawings have mainly been of an illustrative or figurative nature—their primary purpose has been to depict the structure of an object. This purpose remained predominant until well into the second half of the nineteenth century, rendering little need for arrows.[6]

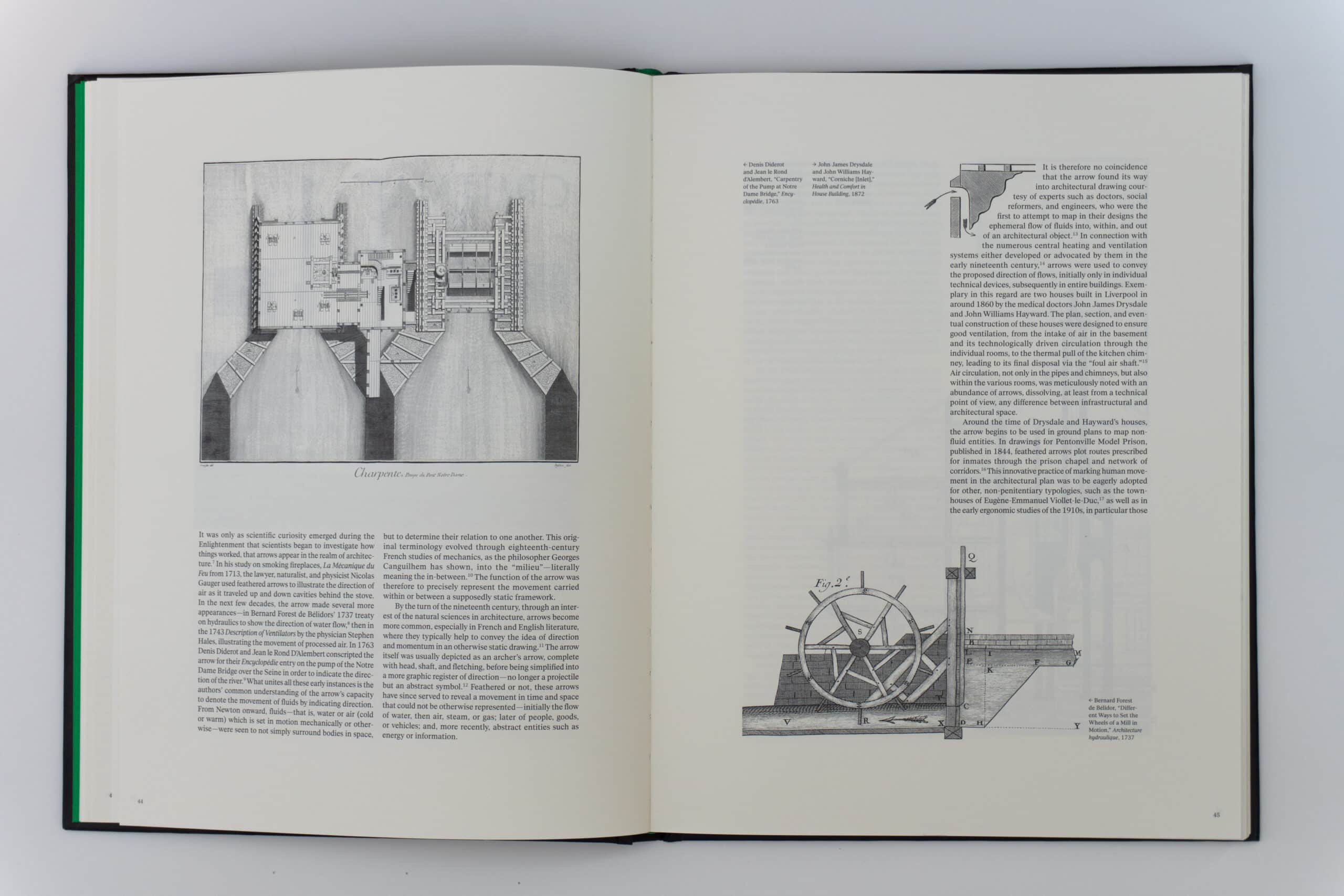

It was only as scientific curiosity emerged during the Enlightenment that scientists began to investigate how things worked, that arrows appear in the realm of architecture.[7] In his study on smoking fireplaces, La Mécanique du Feu from 1713, the lawyer, naturalist, and physicist Nicolas Gauger used feathered arrows to illustrate the direction of air as it traveled up and down cavities behind the stove. In the next few decades, the arrow made several more appearances—in Bernard Forest de Bélidors’ 1737 treaty on hydraulics to show the direction of water flow, then in the 1743 Description of Ventilators by the physician Stephen Hales, illustrating the movement of processed air.[8] In 1763 Denis Diderot and Jean le Rond D’Alembert conscripted the arrow for their Encyclopédie entry on the pump of the Notre Dame Bridge over the Seine in order to indicate the direction of the river.[9] What unites all these early instances is the authors’ common understanding of the arrow’s capacity to denote the movement of fluids by indicating direction. From Newton onward, fluids—that is, water or air (cold or warm) which is set in motion mechanically or otherwise—were seen to not simply surround bodies in space, but to determine their relation to one another. This original terminology evolved through eighteenth-century French studies of mechanics, as the philosopher Georges Canguilhem has shown, into the ‘milieu’—literally meaning the in between.[10] The function of the arrow was therefore to precisely represent the movement carried within or between a supposedly static framework.

By the turn of the nineteenth century, through an interest of the natural sciences in architecture, arrows become more common, especially in French and English literature, where they typically help to convey the idea of direction and momentum in an otherwise static drawing.[11] The arrow itself was usually depicted as an archer’s arrow, complete with head, shaft, and fletching, before being simplified into a more graphic register of direction—no longer a projectile but an abstract symbol.[12] Feathered or not, these arrows have since served to reveal a movement in time and space that could not be otherwise represented—initially the flow of water, then air, steam, or gas; later of people, goods, or vehicles; and, more recently, abstract entities such as energy or information.

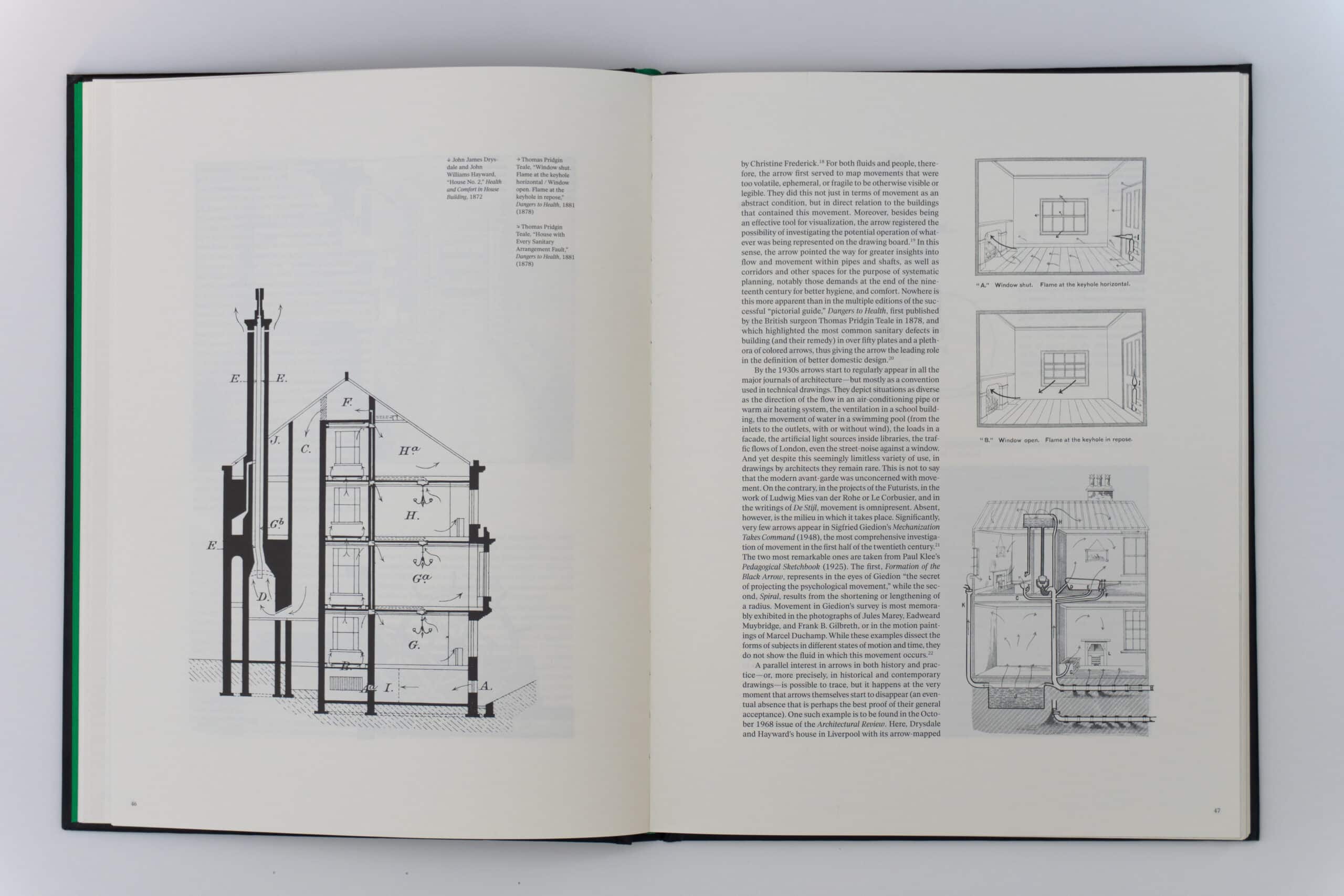

It is therefore no coincidence that the arrow found its way into architectural drawing courtesy of experts such as doctors, social reformers, and engineers, who were the first to attempt to map in their designs the ephemeral flow of fluids into, within, and out of an architectural object.[13] In connection with the numerous central heating and ventilation systems either developed or advocated by them in the early nineteenth century, arrows were used to convey the proposed direction of flows, initially only in individual technical devices, subsequently in entire buildings.[14] Exemplary in this regard are two houses built in Liverpool in around 1860 by the medical doctors John James Drysdale and John Williams Hayward. The plan, section, and eventual construction of these houses were designed to ensure good ventilation, from the intake of air in the basement and its technologically driven circulation through the individual rooms, to the thermal pull of the kitchen chimney, leading to its final disposal via the ‘foul air shaft.’[15] Air circulation, not only in the pipes and chimneys, but also within the various rooms, was meticulously noted with an abundance of arrows, dissolving, at least from a technical point of view, any difference between infrastructural and architectural space.

Around the time of Drysdale and Hayward’s houses, the arrow begins to be used in ground plans to map non-fluid entities. In drawings for Pentonville Model Prison, published in 1844, feathered arrows plot routes prescribed for inmates through the prison chapel and network of corridors.[16] This innovative practice of marking human movement in the architectural plan was to be eagerly adopted for other, non-penitentiary typologies, such as the townhouses of Eugène-Emmanuel Viollet-le-Duc, as well as in the early ergonomic studies of the 1910s, in particular those by Christine Frederick.[17][18] For both fluids and people, therefore, the arrow first served to map movements that were too volatile, ephemeral, or fragile to be otherwise visible or legible. They did this not just in terms of movement as an abstract condition, but in direct relation to the buildings that contained this movement. Moreover, besides being an effective tool for visualisation, the arrow registered the possibility of investigating the potential operation of whatever was being represented on the drawing board.[19] In this sense, the arrow pointed the way for greater insights into flow and movement within pipes and shafts, as well as corridors and other spaces for the purpose of systematic planning, notably those demands at the end of the nineteenth century for better hygiene, and comfort. Nowhere is this more apparent than in the multiple editions of the successful ‘pictorial guide,’ Dangers to Health, first published by the British surgeon Thomas Pridgin Teale in 1878, and which highlighted the most common sanitary defects in building (and their remedy) in over fifty plates and a plethora of coloured arrows, thus giving the arrow the leading role in the definition of better domestic design.[20]

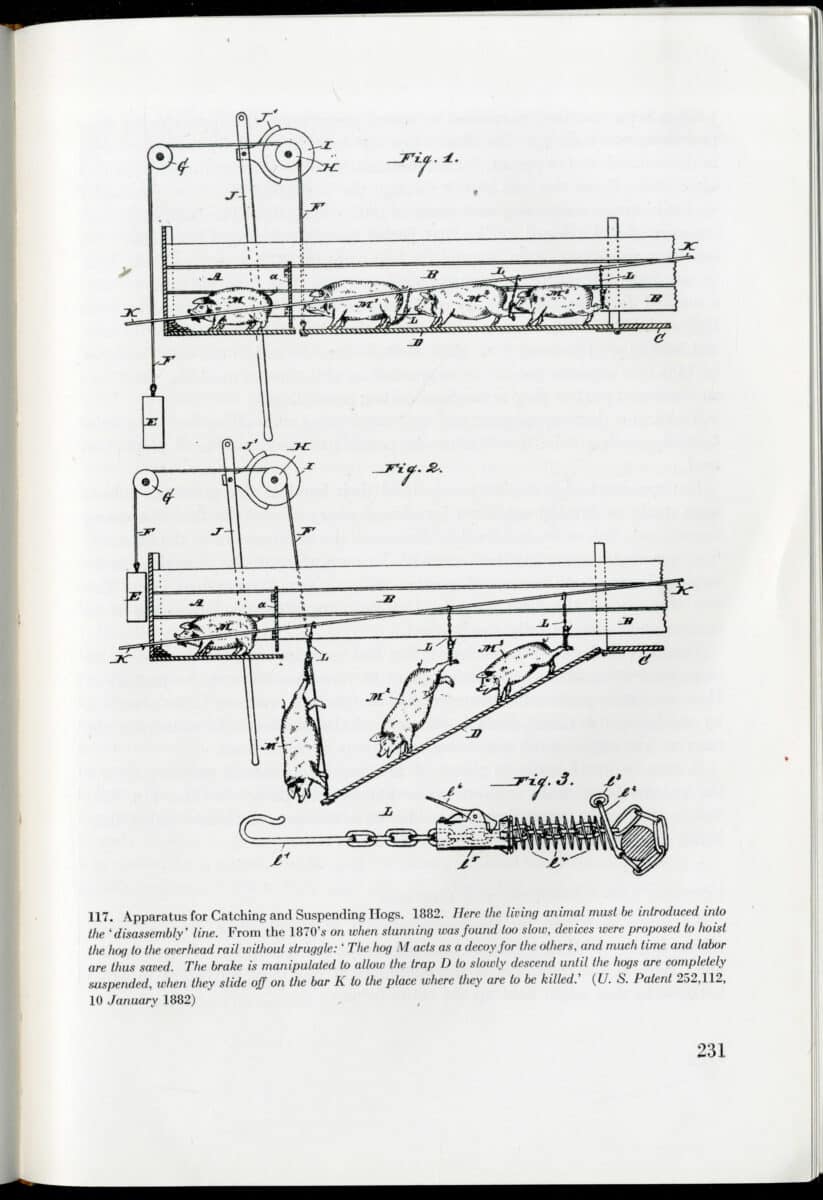

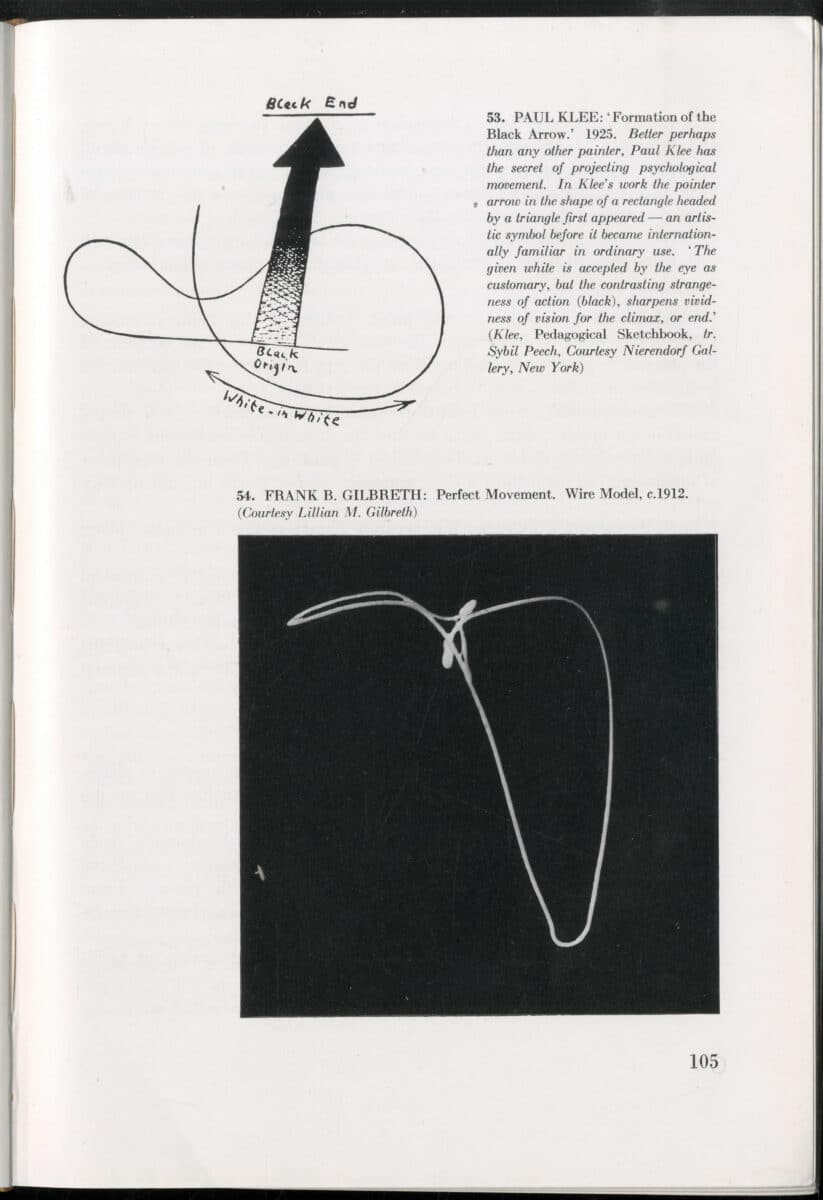

By the 1930s arrows start to regularly appear in all the major journals of architecture—but mostly as a convention used in technical drawings. They depict situations as diverse as the direction of the flow in an air-conditioning pipe or warm air heating system, the ventilation in a school building, the movement of water in a swimming pool (from the inlets to the outlets, with or without wind), the loads in a facade, the artificial light sources inside libraries, the traffic flows of London, even the street-noise against a window. And yet despite this seemingly limitless variety of use, in drawings by architects they remain rare. This is not to say that the modern avant-garde was unconcerned with movement. On the contrary, in the projects of the Futurists, in the work of Ludwig Mies van der Rohe or Le Corbusier, and in the writings of De Stijl, movement is omnipresent. Absent, however, is the milieu in which it takes place. Significantly, very few arrows appear in Sigfried Giedion’s Mechanization Takes Command (1948), the most comprehensive investigation of movement in the first half of the twentieth century.[21] The two most remarkable ones are taken from Paul Klee’s Pedagogical Sketchbook (1925). The first, Formation of the Black Arrow, represents in the eyes of Giedion ‘the secret of projecting the psychological movement,’ while the second, Spiral, results from the shortening or lengthening of a radius. Movement in Giedion’s survey is most memorably exhibited in the photographs of Jules Marey, Eadweard Muybridge, and Frank B. Gilbreth, or in the motion paintings of Marcel Duchamp. While these examples dissect the forms of subjects in different states of motion and time, they do not show the fluid in which this movement occurs.[22]

A parallel interest in arrows in both history and practice—or, more precisely, in historical and contemporary drawings—is possible to trace, but it happens at the very moment that arrows themselves start to disappear (an eventual absence that is perhaps the best proof of their general acceptance). One such example is to be found in the October 1968 issue of the Architectural Review. Here, Drysdale and Hayward’s house in Liverpool with its arrow-mapped ventilation-system illustrates an article by Reyner Banham on the ‘Dark Satanic Century,’ an introduction to the history of artificial ventilation in interiors and a preview of the eponymous chapter of his broad-ranging study of the well-tempered environment of 1969. More than anywhere else, the full extent of Banham’s future book, through his wink to the preludes and fugues of Johann Sebastian Bach’s Well-Tempered Clavier, becomes evident as a plea to integrate all the technical mastery of all the major and minor keys at the turn of a new era.[23]

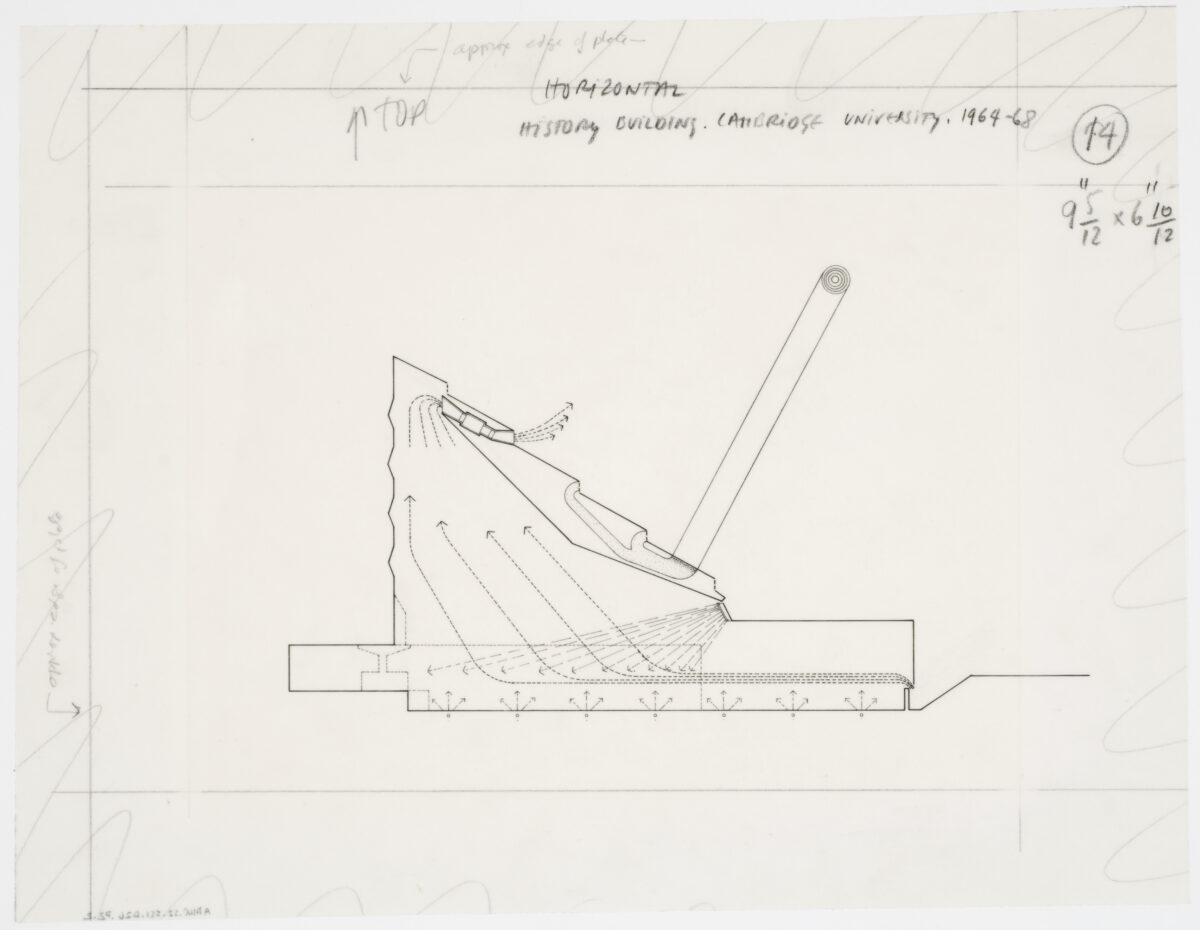

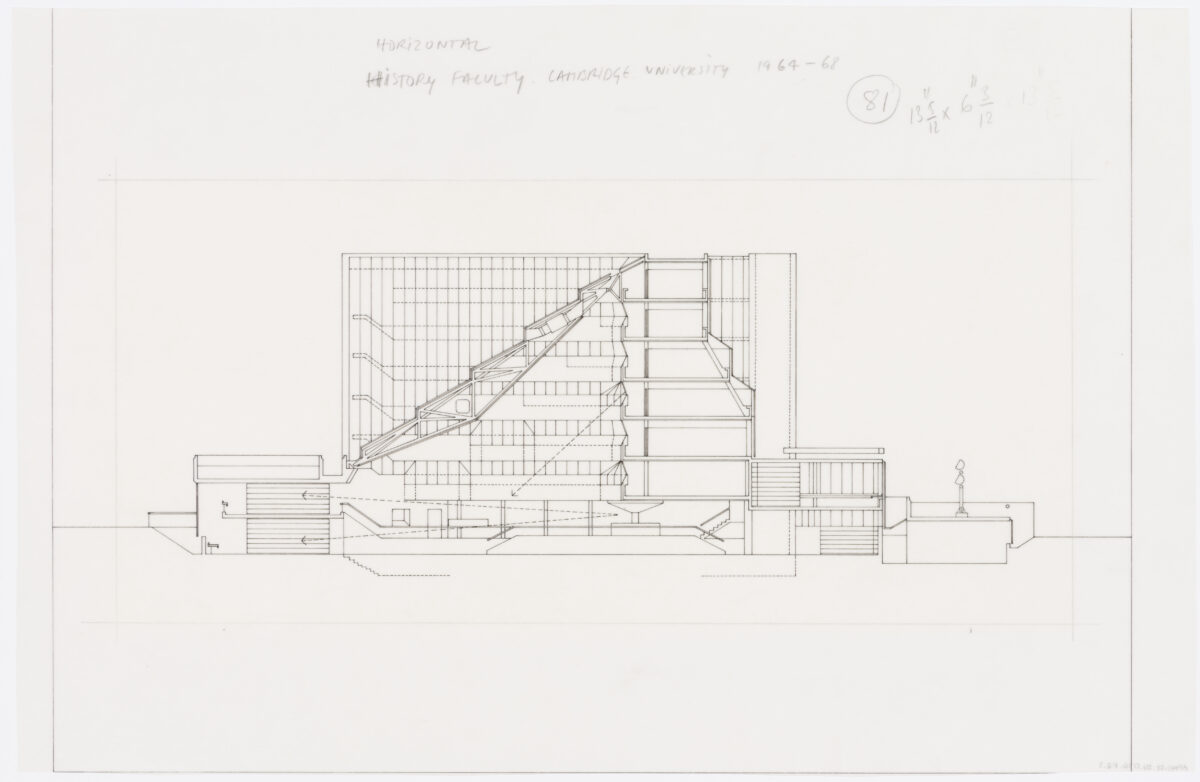

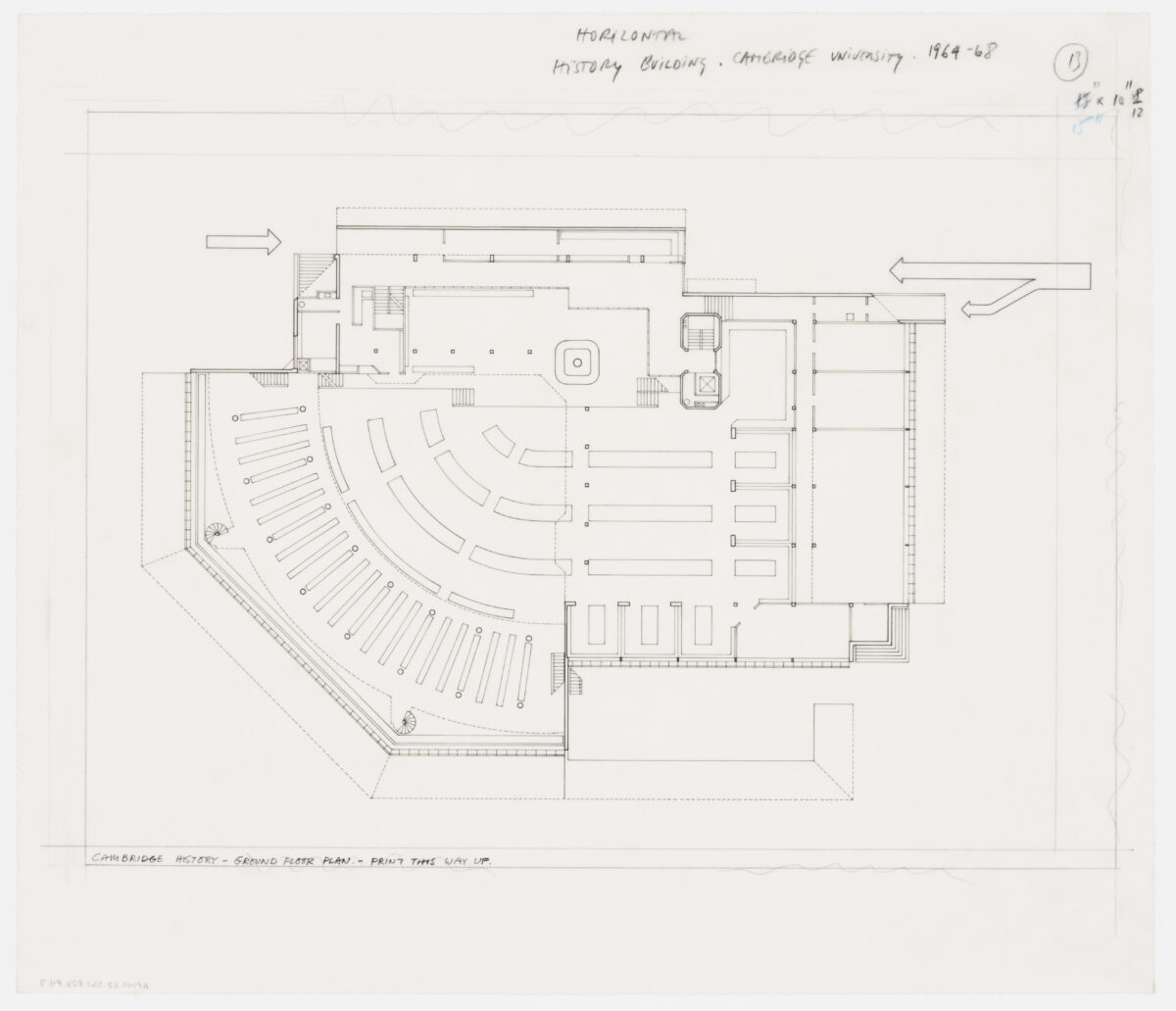

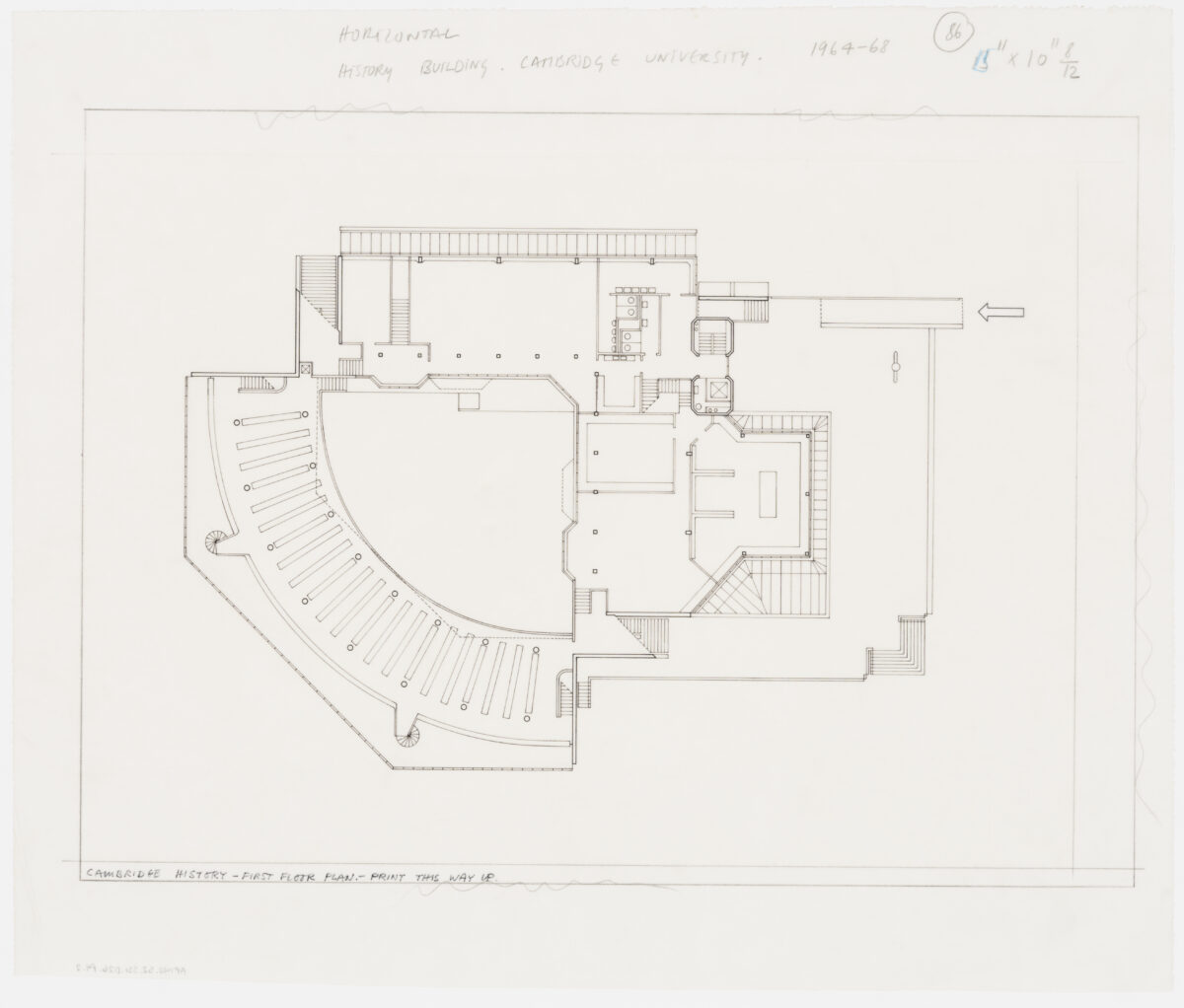

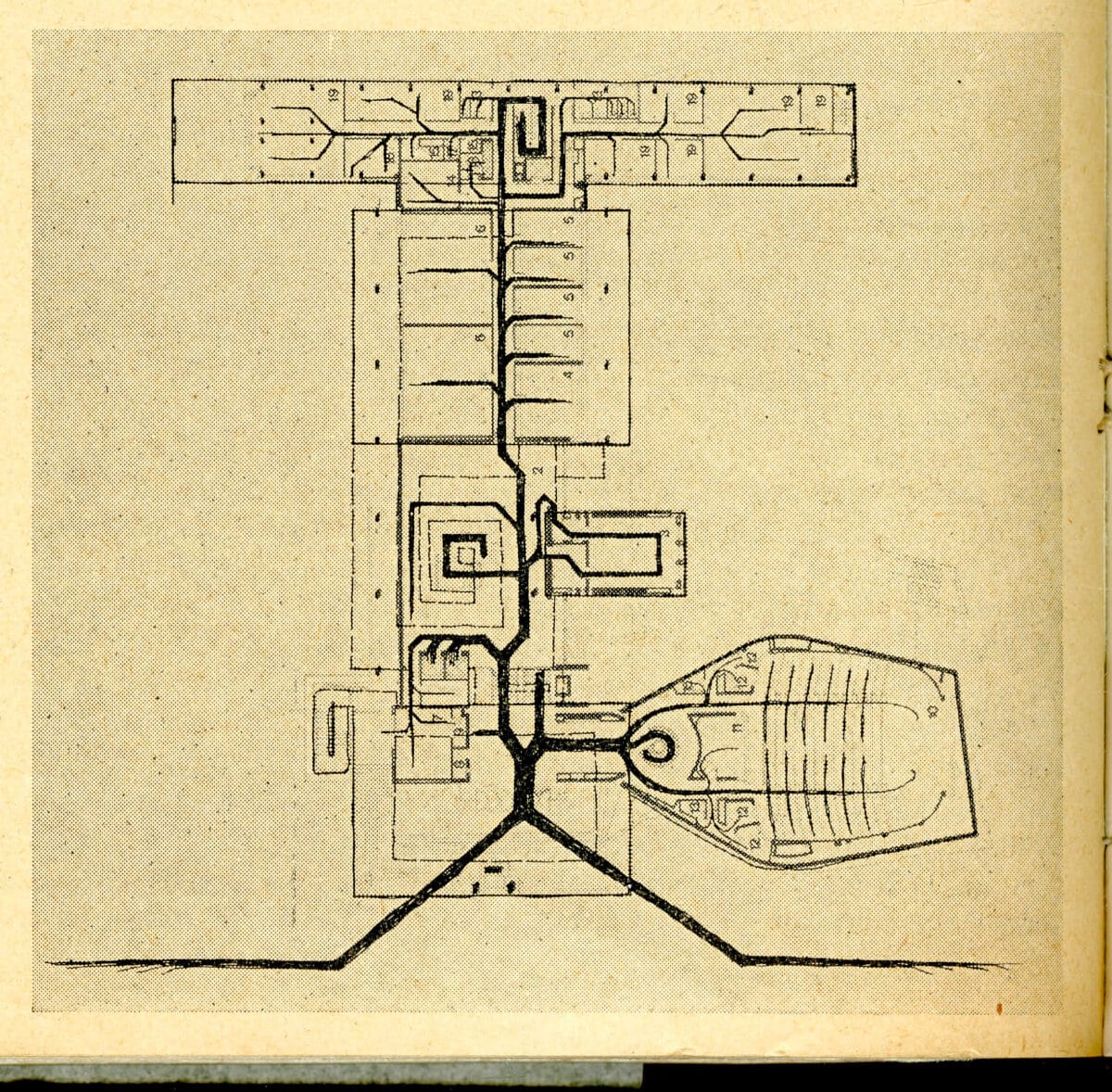

That this new era was already playing out was acknowledged by Banham just two months later in the same journal when discussing James Stirling’s History Faculty library building in Cambridge (1968), whose ‘environmental mechanics’ were amply illustrated by arrows across accompanying sections and plans.[24] While on paper Banham had been investigating past instances of attempts by Drysdale and Hayward to control the architectural climate, Stirling was busy attempting to control the same thing in red bricks and mortar, steel and glass, underfloor and ceiling heating, insulated double-glazing, and ventilation systems (both mechanical and natural), inducing the same well-tempered environment the critic was championing.[25] But however present the arrows are in these instances, they are never explicitly mentioned. Both Stirling and Banham evidently had more faith in their audience than Thomas Pridgin Teale, who eighty years earlier in Sanitary Defects, had been obliged to explain that ‘the course and escape of sewer gases are indicated by blue arrows.’[26]

There is one small but meaningful difference between the arrows in Drysdale and Hayward’s drawing and those that appear in Stirling’s project. In addition to the curved arrows, which were the nineteenth-century convention for representing the circulation of fresh or foul air, the plans and sections for Cambridge introduce straight arrows. Following their trajectory reveals a concern that would have been overlooked by anyone who, like Banham, was obsessed with the climatically controlled environment. As Stirling’s various arrows for Cambridge reveal, ‘environment’ implied not merely technologically controlled climatic parameters (again, as represented in curved arrows) but, more ambitiously, architectural and spatial ones. This effect is succinctly represented in a sectional drawing that uses a pair of straight directional arrows to chart the gaze of the librarian overseeing the annular, slightly recessed complex of the reading room, stacks, and central lending desk. The visual arrangement enables the entire space to be monitored at a single glance, a feature evidently crucial to Stirling’s success in the competition—as in a prison, as one Cambridge don sniped.[27][28] Indeed, just like a panopticon, the assortment of shelves in the library are separated from each other by a corridor and are back—lit, allowing them to be viewed from the central desk, which again, true to Bentham’s ideal prison, lies in the darkest area, its occupant seeing everything without ever being seen by the reader.[29]

But if the library can be read as an apparatus, literally as well as metaphorically, which is determined by its concentrated disposition of figures, volumes, gazes, and light around a quarter-circle, it differs in a significant way from the disciplinary dimension of the prison. For the central lending desk not only is the preserve of the librarian but also houses the technical controls for the building’s lighting, ventilation, and heating (as in the Staatsbibliothek, built in Berlin by Hans Scharoun that same year).[30] It organises and guides the movement of users on the ground floor while supposedly controlling their well being. In Cambridge what is at stake is less the even distribution of bodies in space than the control of a multi-layered visual, climatic, and spatial environment, whose borders are blurred by a combination of the white light of the ceiling, the atmospheric conditions of the reading room, and the open plan at the ground floor.

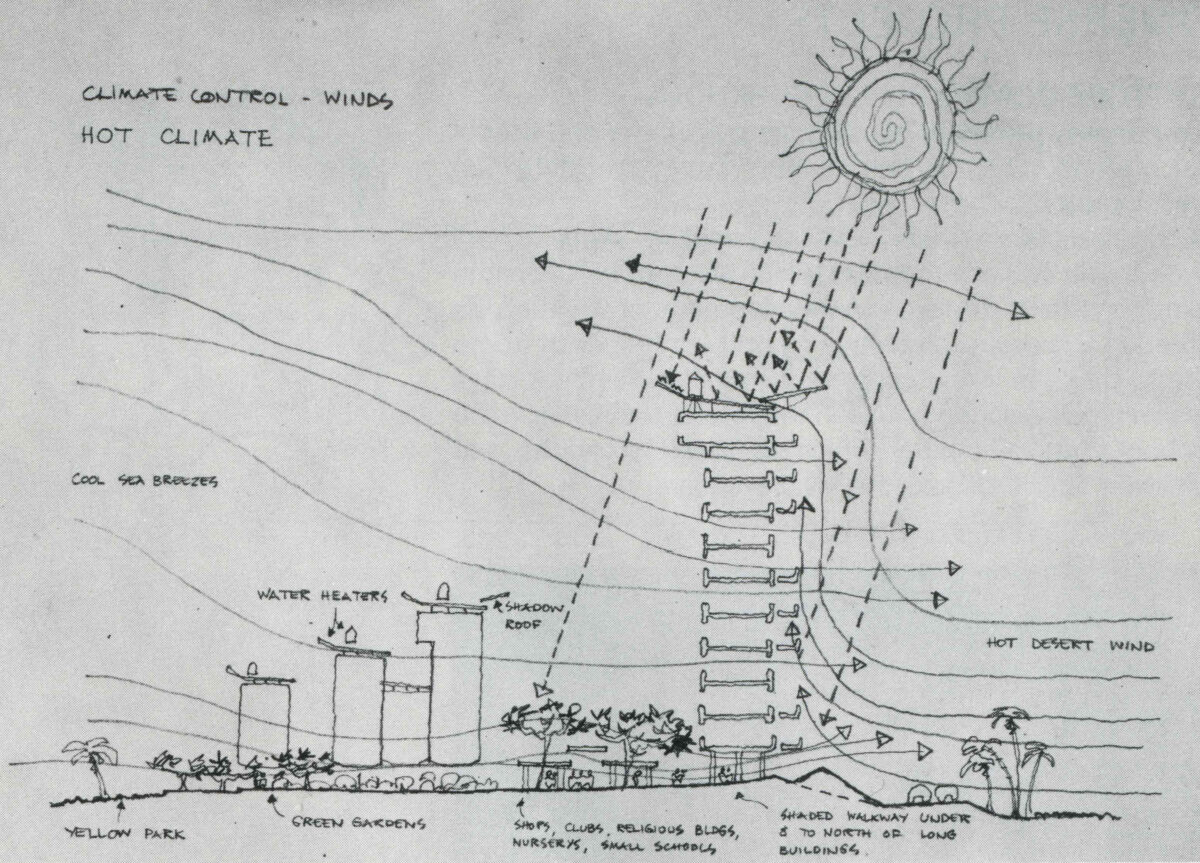

In the Cambridge project arrows reveal concerns by mapping out and controlling climatic conditions, social relations, or organisational matters. Their scope, to stay with Stirling’s work, extends to picturesque dispositions in St. Andrews (1964-1967; where the rows of the student rooms open to the wider landscape), to structural information (as in his unbuilt Dorman-Long Headquarters in Middlesbrough of 1965, where the arrow uncovers forces otherwise not visible), to infrastructural provisions in the Leicester Engineering Building (1963; a building that could also be read as a circulation diagram) or to a notational device indicating the movement of people (those in a hurry at Leicester or those strolling through the galleries in Stuttgart; 1979-1984).

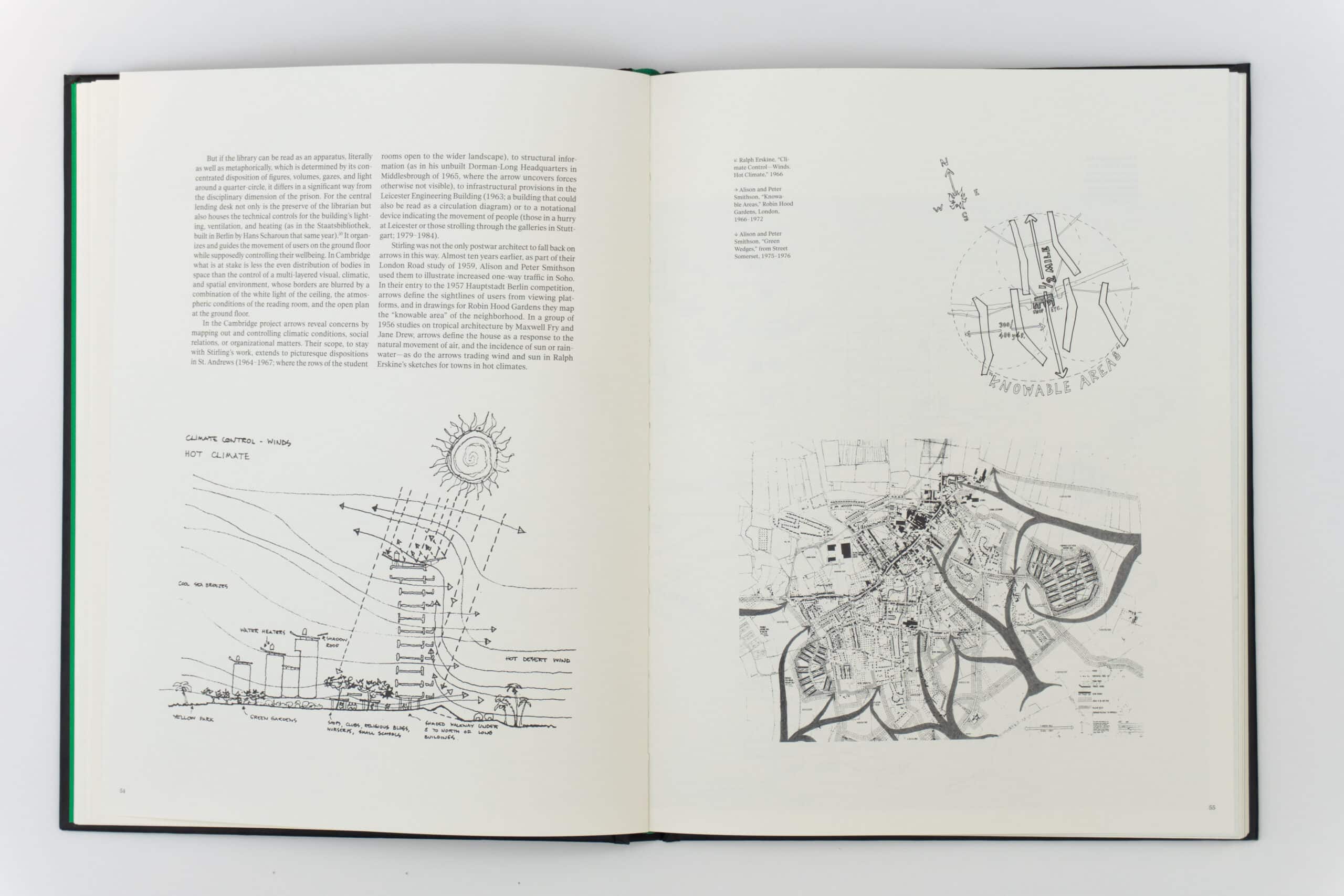

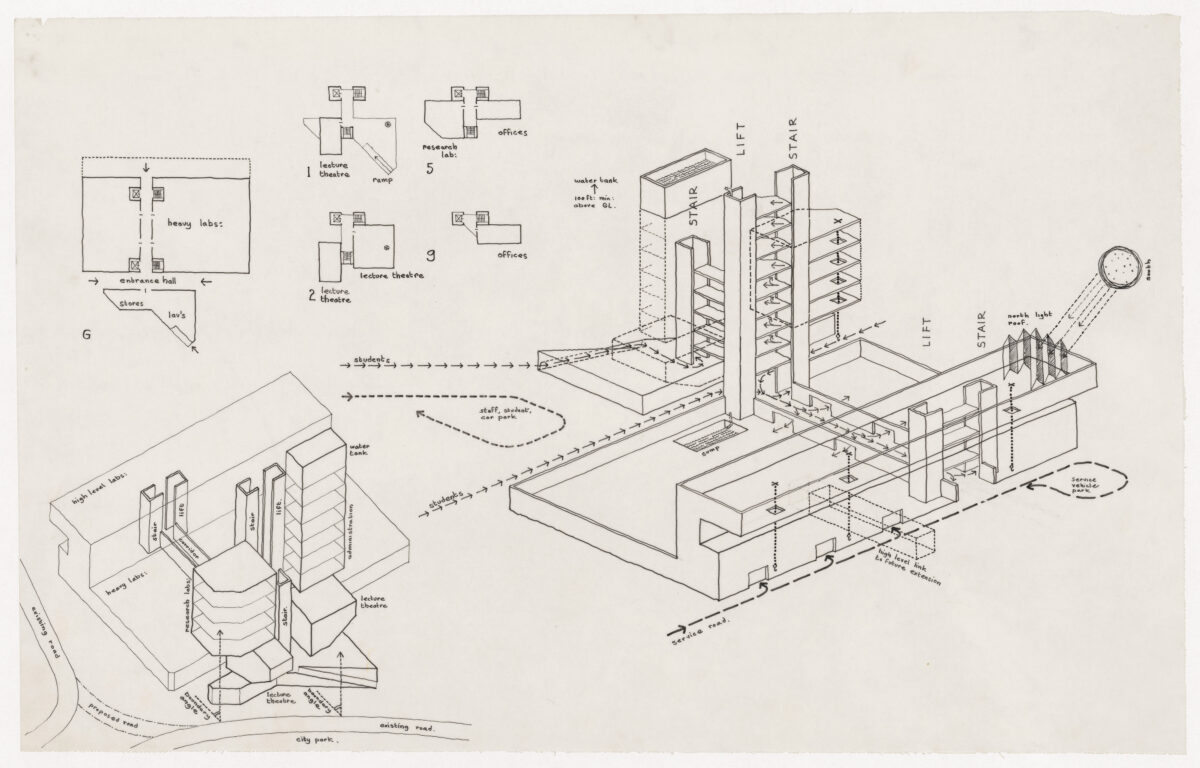

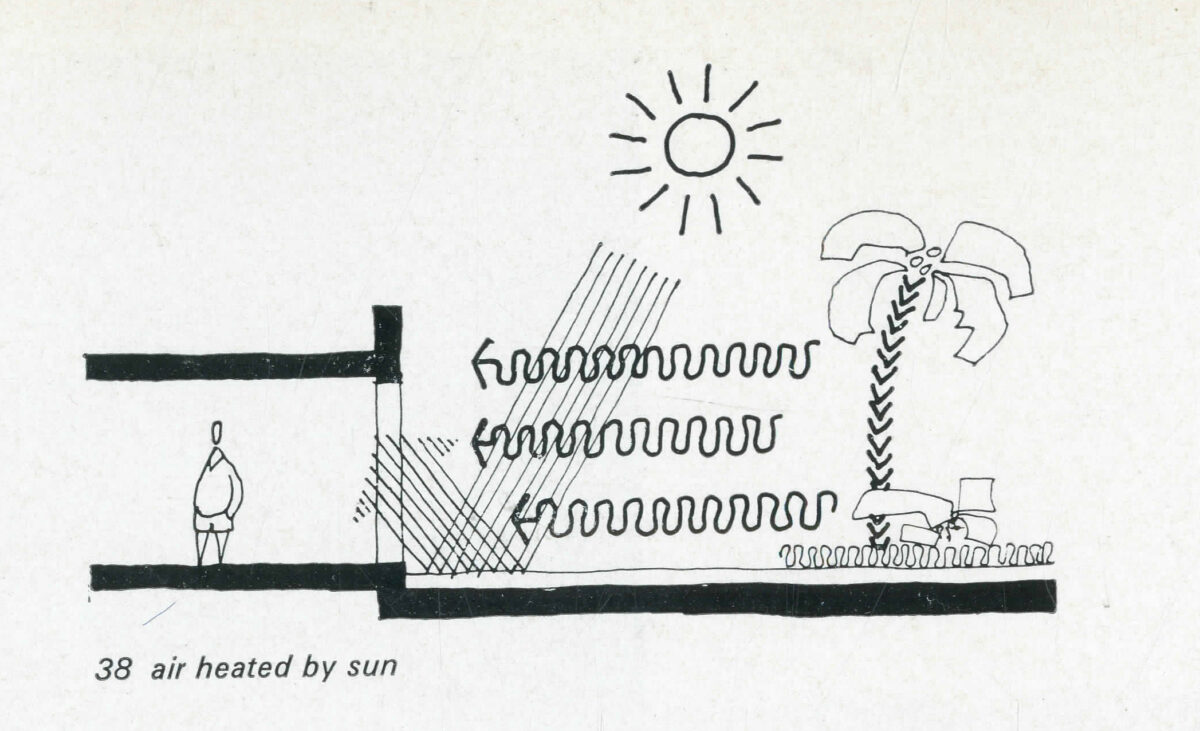

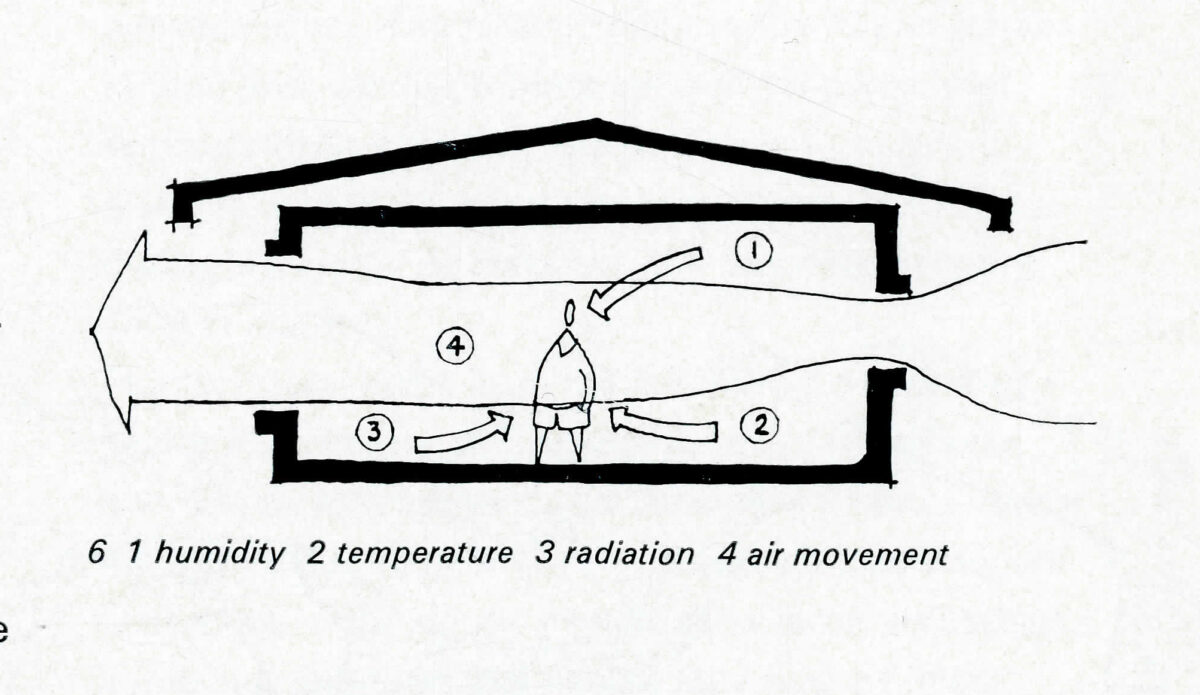

Stirling was not the only postwar architect to fall back on arrows in this way. Almost ten years earlier, as part of their London Road study of 1959, Alison and Peter Smithson used them to illustrate increased one-way traffic in Soho. In their entry to the 1957 Hauptstadt Berlin competition, arrows define the sight-lines of users from viewing platforms, and in drawings for Robin Hood Gardens they map the ‘knowable area’ of the neighbourhood. In a group of 1956 studies on tropical architecture by Maxwell Fry and Jane Drew, arrows define the house as a response to the natural movement of air, and the incidence of sun or rainwater, as do the arrows trading wind and sun in Ralph Erskine’s sketches for towns in hot climates.

Within all these drawings are curved or straight arrows. Yet, there are also other kinds of arrows that not only represent movement but also qualify it. This is achieved in one of two ways: arrows either stand in for the mass of movement and match its contours, or they convey the intensity or density of movement by replicating themselves. In Cambridge, for instance, arrows that map the ins and outs of the floor plans are shown at different widths, splitting into different smaller branches depending on the various user flows and sequences inside and outside the building. In the Drew and Fry studies on natural ventilation, the changing width of the arrow indicates the velocity of the wind, while in other drawings, the intensity of the sun is reflected in the compact arrangement of several arrows in parallel. Returning to the Smithsons’ London Road study, the precision of the movement to be achieved in the planning of the inner-city traffic is represented by the high density of arrows that map out the equally dense net of one-way streets.[31] Arrows in these projects not only mimic movement but, more importantly, quantify performance—in the case of the London Road study, it was the provision for a three hundred percent increase in traffic over the next thirty years.

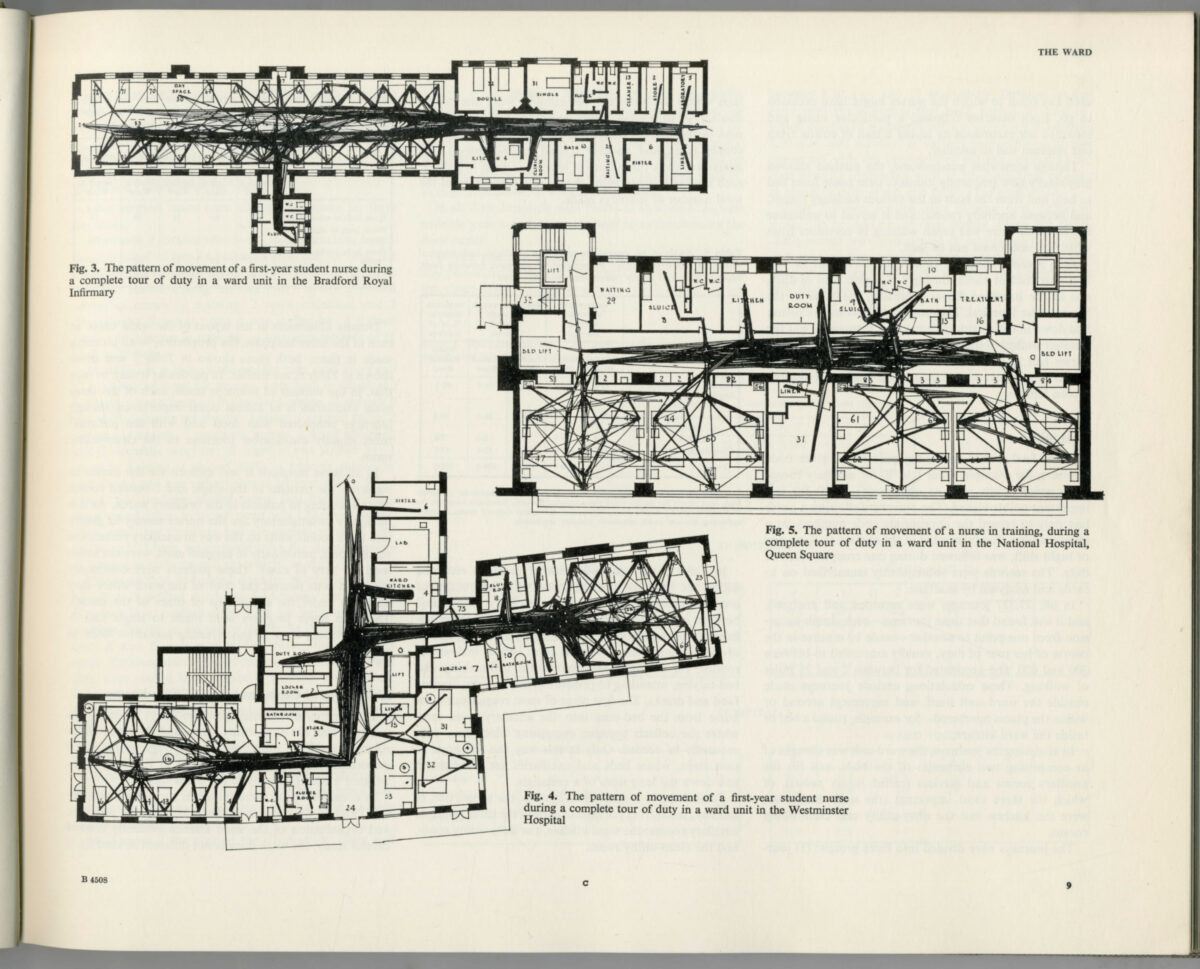

In this sense, the arrow moves beyond architecture towards the realm of the social sciences, appearing across charts, graphs, and reports, recording data in real time. A particularly striking example involves no arrows at all, but a ‘trail of cotton’ used in 1955 by Richard Llewelyn-Davies while leading a team of architects, historians, physicians, nurses, statisticians, and accountants as part of the Nuffield Foundation’s first systematic investigation of postwar hospital environments. The resulting publication, Studies in the Functions and Design of Hospitals, recorded the trajectories of nurses in different ward units, not unlike earlier studies by Christine Fredericks, which focused on the movements of housewives in kitchens, or Alexander Klein’s research into the habitation of flats. For the Nuffield project, the research group methodically charted the movement patterns and frequencies of every nurse at different stages of education. These routes were individually recorded on hospital plans using trails of stretched cotton wool. Inasmuch that arrows had been used by architects to animate the otherwise invisible or hidden infrastructure of static objects, this method enabled an even greater-and literal-degree of transparency: opaque crossings, created by overlapping routes, allowed researchers to identify the principal movements and the critical circulation points inside the ward.[32] Even if the transformation of the arrow back into its geometrical progenitor, the line, might appear as a return to a more conventional art-historical lineage (in which the line demarcates a wall), it is not. Instead, it follows a trajectory in which the line delineates the movement between the walls, connecting two points on a plan, as seen in the single strokes darkening the hospital floor where the movements were most frequent, and grinding around every corner of the contorted geometry of the wards.

The use of arrows (or a trail of cotton) as both a design tool and medium of representation differs from earlier incarnations, such as those seen in the planning of heating systems, say of the Houses of Parliament by the chemist David Boswell Reid in the mid-nineteenth century up to those used by Maxwell Fry in his analysis of the Sun House in the 1930s. During this period, with the exception of the heating or ventilating infrastructure, questions of disposition and composition dominated the architect’s intentions. As Fry writes of his Hampstead project: ‘All architects know that ‘design’ is the inherent result of the proper planning of a building and the arrangement of its parts.’[33] In line with his argument, the house follows the latest recommendations in terms of its orientation while answering certain economic considerations regarding circulation. And yet its formal expression still corresponds to the purist canon. In the built environment of the postwar years, however, this attitude changes as the good management of ‘fluids’ and their thorough control begin to dominate the whole building and its spaces. Evidence of this is not merely limited to the imposing images of the avant-garde, as epitomised by the shafts of Warren Chalk’s capsule towers (1964) or Michael Webb’s furniture factory (1957-1958), whose rhetorically inflated forms later transpired in the heroic projects of Richard Rogers and Renzo Piano. The careful, even visionary, design of infrastructure comes through in the numerous less emphatic proposals and built works that defined architecture throughout Britain in the 1950s and 1960s.

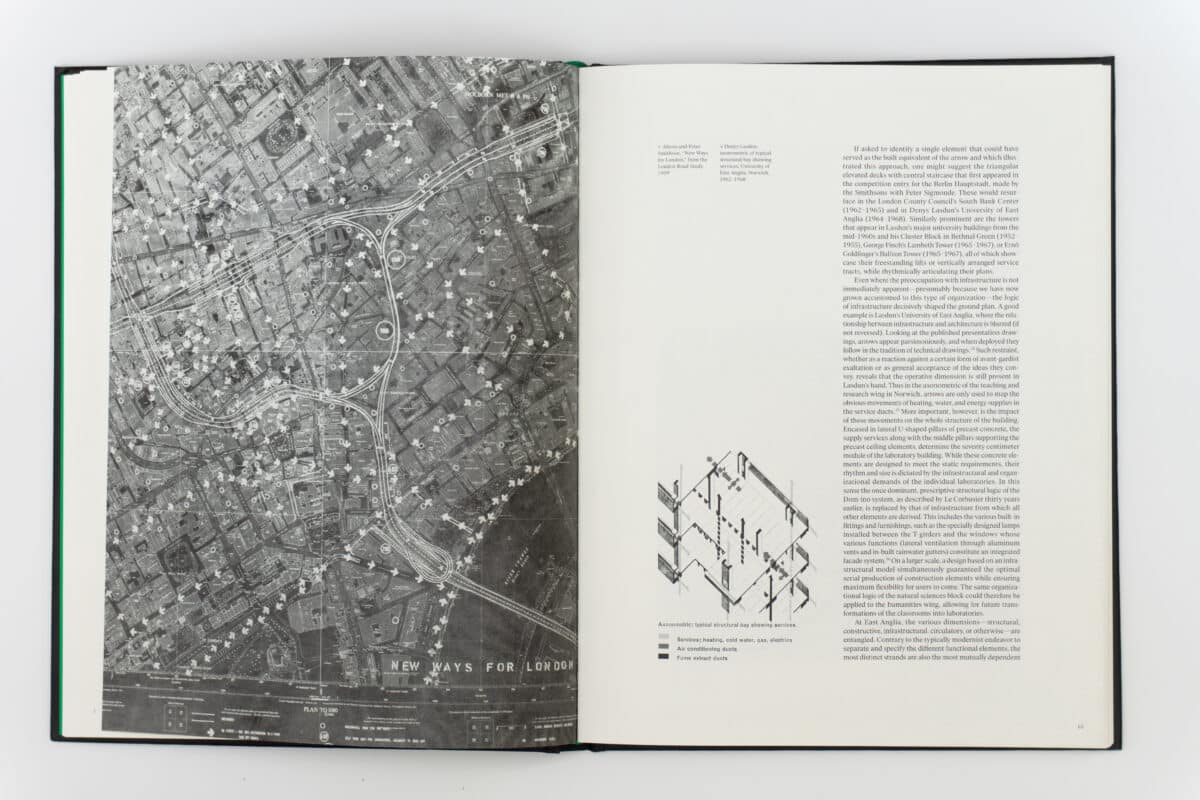

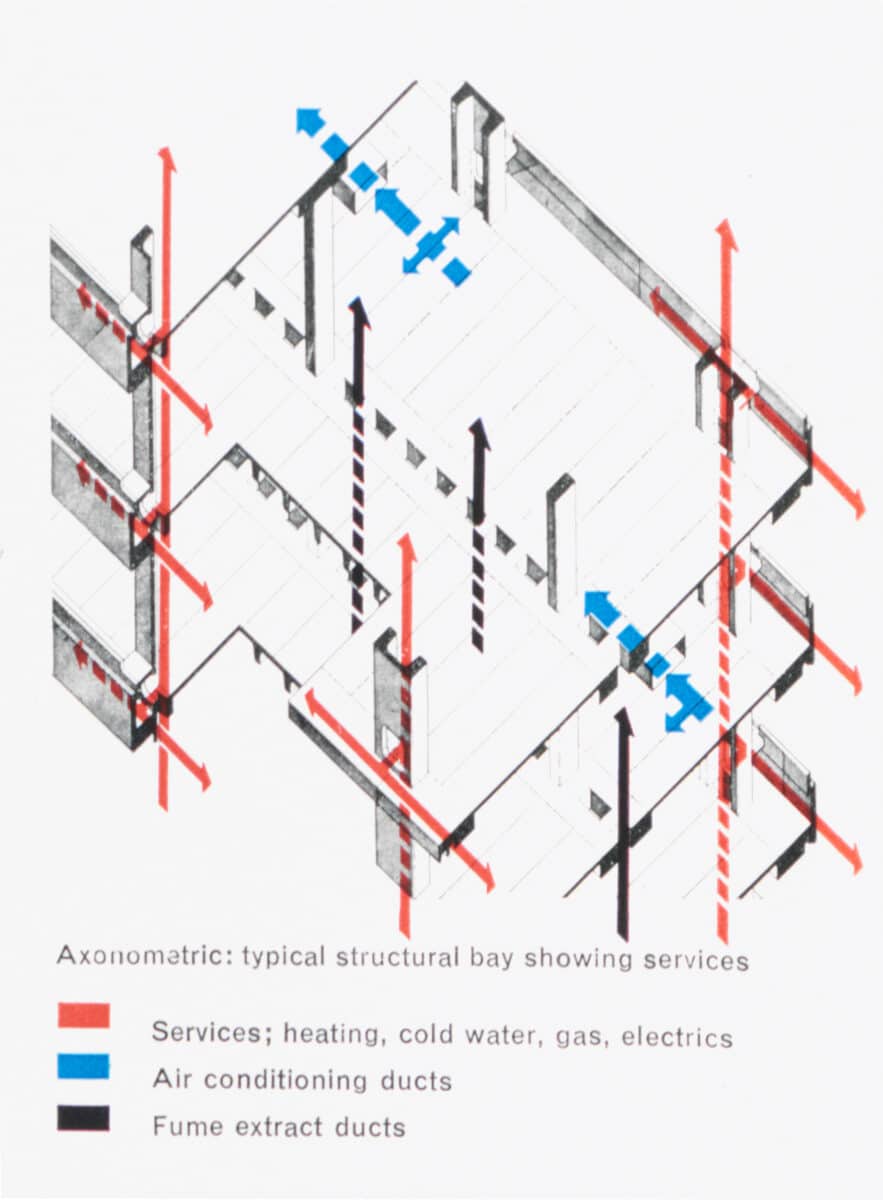

If asked to identify a single element that could have served as the built equivalent of the arrow and which illustrated this approach, one might suggest the triangular elevated decks with central staircase that first appeared in the competition entry for the Berlin Hauptstadt, made by the Smithsons with Peter Sigmonde. These would resurface in the London County Council’s South Bank Center (1962-1965) and in Denys Lasdun’s University of East Anglia (1964-1968). Similarly prominent are the towers that appear in Lasdun’s major university buildings from the mid-1960s and his Cluster Block in Bethnal Green (1952- 1955), George Finch’s Lambeth Tower (1965-1967), or Ernö Goldfinger’s Balfron Tower (1965-1967), all of which showcase their freestanding lifts or vertically arranged service tracts, while rhythmically articulating their plans.

Even where the preoccupation with infrastructure is not immediately apparent—presumably because we have now grown accustomed to this type of organisation—the logic of infrastructure decisively shaped the ground plan. A good example is Lasdun’s University of East Anglia, where the relationship between infrastructure and architecture is blurred (if not reversed). Looking at the published presentation drawings, arrows appear parsimoniously, and when deployed they follow in the tradition of technical drawings.[34] Such restraint, whether as a reaction against a certain form of avantgardist exaltation or as general acceptance of the ideas they convey, reveals that the operative dimension is still present in Lasdun’s hand. Thus in the axonometric of the teaching and research wing in Norwich, arrows are only used to map the obvious movements of heating, water, and energy supplies in the service ducts.[35] More important, however, is the impact of these movements on the whole structure of the building. Encased in lateral U-shaped pillars of precast concrete, the supply services along with the middle pillars supporting the precast ceiling elements, determine the seventy centimetre module of the laboratory building. While these concrete elements are designed to meet the static requirements, their rhythm and size is dictated by the infrastructural and organisational demands of the individual laboratories. In this sense the once dominant, prescriptive structural logic of the Domino system, as described by Le Corbusier thirty years earlier, is replaced by that of infrastructure from which all other elements are derived. This includes the various built-in fittings and furnishings, such as the specially designed lamps installed between the T-girders and the windows whose various functions (lateral ventilation through aluminum vents and in-built rainwater gutters) constitute an integrated facade system.[36] On a larger scale, a design based on an infrastructural model simultaneously guaranteed the optimal serial production of construction elements while ensuring maximum flexibility for users to come. The same organisational logic of the natural sciences block could therefore be applied to the humanities wing, allowing for future transformations of the classrooms into laboratories.

At East Anglia, the various dimensions—structural, constructive, infrastructural, circulatory, or otherwise—are entangled. Contrary to the typically modernist endeavour to separate and specify the different functional elements, the most distinct strands are also the most mutually dependent on the common performance to be fulfilled: the statics and the organisation of the laboratories; the composition of the facades and the ventilation and heating; prefabrication and use. This entangling is in fact integral to the logic of infrastructure and its attendant issues of performance. Not limited to specialised buildings. such as laboratories or office complexes, it featured much more generally across postwar modernism and its corresponding spatial concepts.

The theoretical and spatial implications of Lasdun’s approach at East Anglia were to be addressed in another of his buildings, the Royal College of Physicians, built in London from 1959 to 1964. While redolent of his more formally ambitious projects, a variety of innovative technologies allowed it to correspond fully to what was then expected for a building of its standard. Heating panels located in the floor and ceiling, for instance, served public areas and offices located at the rear, while individual air-conditioning units were installed in the assembly rooms, library, conference room, and canteen. A radio system in the main auditorium was designed for simultaneous translation, and complementing the more conventional networks conveying energy or water was a TV system interlinking the various theatres.

None of this, however, is mentioned by Alvin Boyarsky in his elaborate review of the completed project for Architectural Design, which dissects the architect’s parti pris by looking, literally, under the skin. Perhaps more important than the text is an illustration of a Vitruvian Man-not the typical homo ad quadratum, rather his circulatio sanguingis overlaid as a diagram onto the plan of the building.[37] The vascular analogy was precisely Boyarsky’s argument when comparing the layout of the building with a group of four seventeenth-century wooden panels that displayed the arterial system. The English physician William Harvey had used these when presenting his discovery of the continuous circulation of blood before the very same College of Physicians. As Boyarsky writes speaking about the building (not the panels): ‘there are the major arteries, the bifurcations for the limbs, with their secondary and tertiary tributaries; there are the overlapping spirals connecting the organs to each other and to the central spine.’[38]

Again (as in Nuffield) the arrow cedes to circulation routes (this time organic ones). The main path starts at the portico (with its central pillar aligned on this major axis), continues through the foyer to the main auditorium and the spiral staircase that leads to the split-level library. Or, after a further turn, it flows to the assembly room. Alternatively, it moves down from the foyer to the below-ground theatres. Drawn with a thick black stroke that tapers in a point at the end, the movement throughout the building is conceived as a flow modulated by stairs, ceilings, stairs, doors, and windows into a sequence of spatial layers with their own atmosphere: ‘formal, informal, warm, cold, public or private, high or low status,’ as Lasdun would put it years later, when describing the different spatial effects achieved throughout the building by altering the light, proportion, material, and climate.[39]

The Vitruvian Man is notable for establishing the obvious biological analogy between the building and organism, or routes and the circulation system, or an enclosing fabric and cellular membranes (Boyarsky, pushing the comparison further, would underline all these points in his article).[40] What is perhaps more interesting, is when the biological analogy confronted with the ‘environmental mechanics’—not only those highlighted in other buildings of the time, like Stirling’s Cambridge Library, but also those which are equally present in the Royal College of Physicians and yet ignored in the comments of both the architect and the critic. It would, however, be wrong to read this distinction as a simple move away from a mechanistic understanding towards an organistic conception of architecture. These two perspectives—one mechanical, the other biological or vital—do not contradict each another but represent two sides of the same coin. They point towards the extent to which the technical became rooted in a new understanding of the living.[41] The arrows that therefore direct the gaze of a librarian, or distinguish a ‘knowable area,’ or chart the path of a pedestrian or a ship, or even map the acoustic reflection inside a building—and not just these but also the arrowless strokes that illustrate the movements of people—are for sure precise ways of depicting the operational demands put on postwar architecture, but perhaps more importantly they are expressions of a new infrastructurally informed organisation of the human environment.

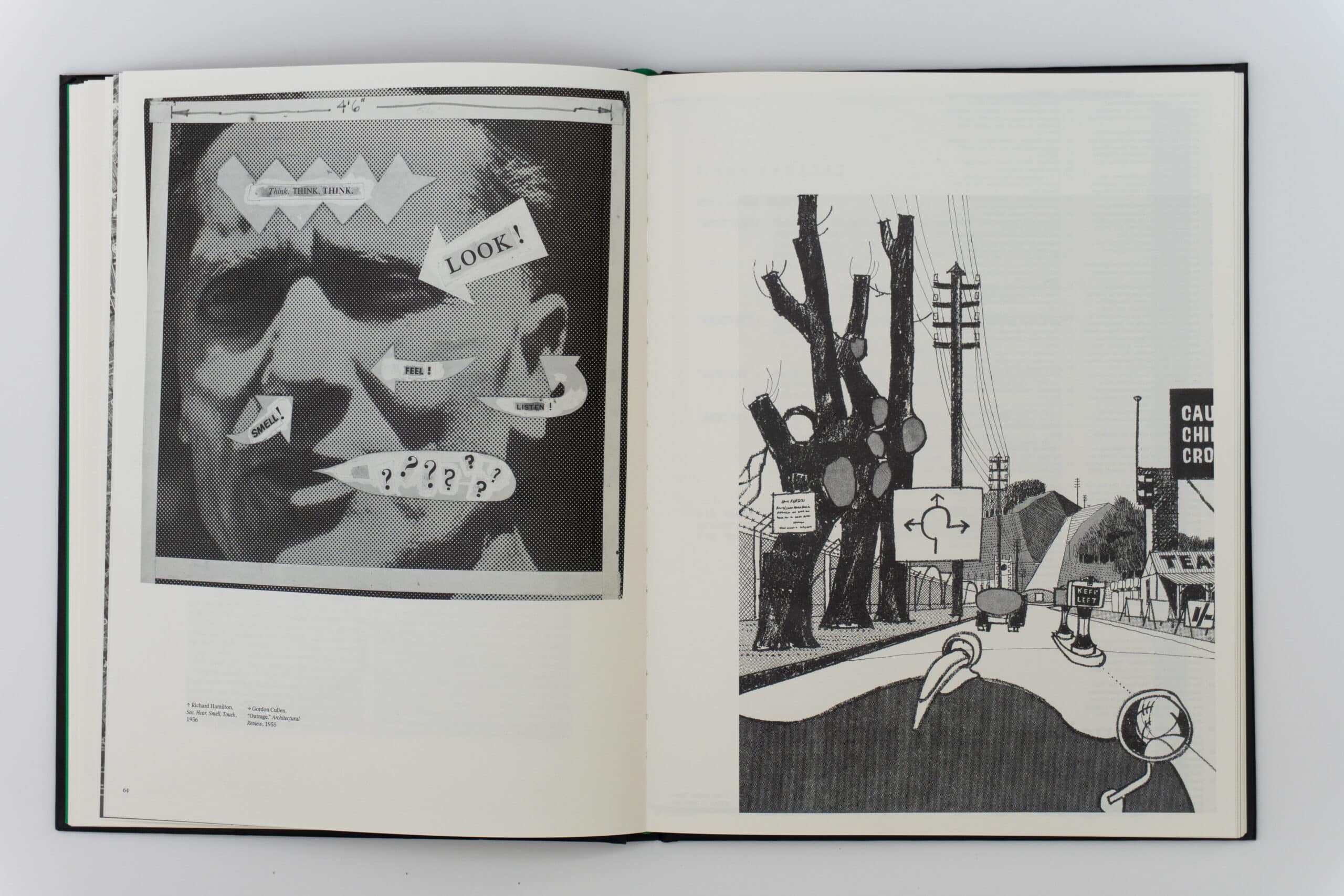

At this point it might be tempting to draw connections between the arrows in architectural plans and others that emerged in the 1950s: the innumerable ones that appeared on roads and on signage along the streets that Gordon Cullen and members of the Townscape movement had critiqued as an outrage (the most improbably yet widespread arrows being those indicating how to circumnavigate a roundabout); the arrows in the psychogeographic map of Guy Debord illustrating the different field of attractions between neighbourhoods in Paris and collaged in the overall installation of Archigram’s 1961 Living City exhibition at the Institute of Contemporary Arts; or the arrows in scientific and, especially, communication studies, which would find their way into the catalogue entry by Richard Hamilton, John Voelcker, and John McHale for the This Is Tomorrow exhibition of 1956.[42] In their collage See, Hear, Smell, Touch, different arrows-long and fat, curved and small with dwindling tails or forming a zigzag pattern-point to the different organs of environmental perception: the eye, nose, mouth as well as the skin. Beyond their variety, what unites them all is the intrinsic semiotic link between the arrow-sign and the action it signifies.

Therein lies the difference between these arrows and those found in the architectural plans (say, of Fry and Drew drawn in the same years) whose particularity lies less in their semiotic than diagrammatic dimension.[43] What makes architecture’s arrows so fundamentally different is that they not only anticipate an action that is yet to happen—that is, they not only signify a signified to come—but, more importantly, they transgress the realm of semiotics altogether. They bring together signs with other materials: diagrams of movement with bricks and mortar, glass and steel, enabling a reality to transform into another state.[44] After all, these arrows not only represent movement in architecture; like the archer’s arrows they were first modelled on, they create it.

Notes

- Iain Jackson and Jessica Holland, The Architecture of Edwin Maxwell Fry and Jane Drew: Twentieth Century Architecture, Pioneer Modernism and the Tropics (Farnham: Ashgate, 2014), 69.

- Ironically, it was Fry’s work preceding his association with Gropius that Hitchcock had been deemed superior. See: Henry-Russell Hitchcock, Modern Architecture in England (New York: The Museum of Modern Art, 1937), 30.

- Willy Boesiger and Oscar Stonorov, eds., Le Corbusier et Pierre Jeanneret: Oeuvre complète 1910-1929, vol. l (Zurich: Girsberger, 1937 (1929)), 208.

- Alexander Klein, ‘Grundrissbildung und Raumgestaltung von Kleinwohnungen und neue Auswertungsmethoden,’ Zentralblatt der Bauverwaltung 48 (1928): 541-49; 35 (1928): 561-568; here 562-563.

- Alvar Aalto, Alvar Aalto: 1922-1962, vol. 1 (Zurich: Les editions de l’architecture Artemis, 1963), 40.

- André Lavarde, ‘La fleche, le signe qui anime les schemas,’ Communication et Languages 109, vol. 3 (1996), 51.

- Moritz Gleich, ‘Bewegung entwerfen. Eine kurze Geschichte des Pfeils im architek tonischen Plan,’ Horizonte: Zeitschrift für Architekturdiskurs 12 (2018), 155-169.

- Ernst Gombrich, ‘Pictorial instructions,’ in Images and Understanding, ed. Horace Barlow, Colin Blakemore, and Miranda Weston-Smith (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1991), 26-45. See also: G. D. Schott: ‘Illustrating Cerebral Function: The Iconography of Arrows,’ Philosophical Transactions: Biological Sciences 355, 1404 (2000), 1789.

- Denis Diderot and Jean le Rond d’Alembert, eds., ‘Charpente: Pompe du Pont Notre Dame,’ in Encyclopédie, ou dictionnaire raisonné des sciences, des arts et des métiers, etc., vol. 2 (Paris, 1763), plate 36.

- Georges Canguilhelm, ‘Le vivant et son milieu,’ in La connaissance de la vie (Paris: Hachette, 1952), 160.

- Lavarde, ‘La flèche, le signe qui anime les schémas,’ 51.

- Rebekka Ladewig, ‘Über die Geschicke des Pfeils,’ in Im Zauber der Zeichen: Beiträge zur Kulturgeschichte des Mediums, ed. Jörn Ahrens and Stephan Braese (Berlin: Vorwerk, 2007), 17-30.

- Gleich, ‘Bewegung entwerfen,’ 164. See also Paul Emmons, ‘Intimate Circulations: Representing Flow in House and City,’ AA Files 51 (Winter 2005): 48-57.

- See Neville S. Billington, ‘A Historical Review of the Art of Heating and Ventilating,’ Architectural Science Review 2 (1959), 118-130.

- John James Drysdale and John Williams Hayward, Health and Comfort in House Building or Ventilation with Warm Air by Self-Acting Suction Power: with Review of the Mode of Calculating the Draught in Hot-Air Flues and with Some Actual Experiments (London: E. & F. N. Spon, 1872): 58, [plate] House No 2.

- See Joshua Jebb, Modern Prisons: Their Construction and Ventilation (London: John Weale, 1844), plate 3.

- Eugène-Emmanuel Viollet-le-Duc, Entretiens sur l’architecture, vol. 2 (Paris: Morel, 1872), 823.

- On kitchen plans and home economics, see Lisa M. Tucker, ‘The Labor-saving Kitchen: Sources for Designs of the Architects’ Small Home Service Bureau,’ Enquiry. The ARCC Journal 11, no. 1 (2014): 52-63. Also, Emmons, ‘Intimate Circulations.’

- See Sybille Kramer, ‘The Mind’s Eye: Visualizing the Non-Visual and the Epistemology of the Line,’ in Image and Imaging in Philosophy, Science and the Arts, ed. Richard Heinrich et al., vol. 2 (Frankfurt: De Gruyter, 2011), 275-287.

- T. Pridgin Teale, Dangers to Health: A Pictorial Guide (London: J. & A. Churchill, 1881 [1878]), xii.

- See Sigfried Giedion, Mechanization Takes Command: A Contribution to Anonymous History (New York: Oxford University Press, 1948).

- Laurin Schwarz proposes an elaborated cultural history of the arrow in the interwar period, ranging from art to film, up to traffic engineering: Laurin Schwarz, Pfeilzeichen und Moderne. Visuelle Ordnungen des Transits van den Avantgarden zur Massenkultur (Master Thesis, Humboldt University, 2022).

- The connection to J. S. Bach (now seemingly obvious) was suggested to me by Virginia Zaretskie in a second-year seminar at the ETH Zurich.

- Reyner Banham: ‘History Faculty, Cambridge,’ Architectural Review 144, vol. 861 (1968), 328-332.

- Banham: ‘History Faculty, Cambridge.’

- Teale, Dangers to Health, 8.

- F. E. Heppenstall, ‘Some Notes on the Services,’ Architectural Review 144, no. 861 (1968), 338.

- See Hugh Brogan, ‘Cambridge Diary,’ Cambridge Review (October 1968), 15.

- See Michel Foucault, Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison (New York: Vintage Books, 1995), 195-228.

- Information given to the author by Matthias Schirren, TU Kaiserslautern.

- See Alison and Peter Smithson, CIAM 59, Otterlo, October 7-15, 1959, 72-79. Also: Colin D. Buchanan, London Road Plans 1900-1970 (London: Greater London Council, 1971), 39.

- Nuffield Trust and University of Bristol, Studies in the Function and Design of Hospitals (London: Oxford University Press, 1955), 8-10.

- Maxwell Fry, ‘Analysis of a building,’ Architects’ Journal 81, 2108 (1935), 909.

- ‘University of East Anglia: Denys Lasdun and Partners,’ Architectural Design 39, 5 (1969), 252.

- ‘University of East Anglia,’ 252.

- ‘University of East Anglia,’ 253.

- Alvin Boyarsky, ‘The Architecture of Etcetera,’ Architectural Design 35, 6 (1965), 269-270.

- Boyarsky, ‘The Architecture of Etcetera,’ 269-270.

- Stephen Greenberg, ‘Lasdun Extends Lasdun: The Royal College of Physicians,’ Architects’ Journal (1994), 17-18.

- Boyarsky, ‘The Architecture of Etcetera,’ 269.

- See also: Georges Canguilhem, ‘Machine et Organisme,’ La connaissance de la vie (Paris: Hachette, 1952), 159.

- See Simon Sadler, The Situationist City (Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 1998), 132-133.

- In his study of architectural modernism in the US, Hyungmin Pai describes the diagram (in a chapter using drawings with arrows from Alexander Klein and others) in a similar way, clarifying its role as an intermediary between object and mind: Hyungmin Pai, The Portfolio and the Diagram: Architecture, Discourse, and Modernity in America (Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 2002): 162-197.

- Building on Felix Guattari’s idea of ‘a-signifying semiotics,’ Moritz Gleich developed this argument in our essay, ‘Stirling’s Arrows,’ AA Files 72 (2016): 67. See also Félix Guattari, Molecular Revolution: Psychiatry and Politics (London: Penguin, 1984).

*

Laurent Stalder is Professor of the History and Theory of Architecture at ETH Zurich, Switzerland, where his teaching and research focus on the intersection of technology with nineteenth, twentieth, and twenty-first-century architecture.

This chapter appears in Laurent Stalder’s recently published book On Arrows (Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press, 2025), 35–66. For more information about the publication see here.